Abstract

Up to 50 % of breast cancer survivors on aromatase inhibitor therapy report musculoskeletal symptoms such as joint and muscle pain, significantly impacting treatment adherence and discontinuation rates. We conducted a secondary data analysis of a nationwide, multi-site, phase II/III randomized, controlled, clinical trial examining the efficacy of yoga for improving musculoskeletal symptoms among breast cancer survivors currently receiving hormone therapy (aromatase inhibitors [AI] or tamoxifen [TAM]). Breast cancer survivors currently receiving AI (N = 95) or TAM (N = 72) with no participation in yoga during the previous 3 months were randomized into 2 arms: (1) standard care monitoring and (2) standard care plus the 4-week yoga intervention (2x/week; 75 min/session) and included in this analysis. The yoga intervention utilized the UR Yoga for Cancer Survivors (YOCAS©®) program consisting of breathing exercises, 18 gentle Hatha and restorative yoga postures, and meditation. Musculoskeletal symptoms were assessed pre- and post-intervention. At baseline, AI users reported higher levels of general pain, muscle aches, and total physical discomfort than TAM users (all P ≤ 0.05). Among all breast cancer survivors on hormonal therapy, participants in the yoga group demonstrated greater reductions in musculoskeletal symptoms such as general pain, muscle aches and total physical discomfort from pre- to post-intervention than the control group (all P ≤ 0.05). The severity of musculoskeletal symptoms was higher for AI users compared to TAM users. Among breast cancer survivors on hormone therapy, the brief community-based YOCAS©® intervention significantly reduced general pain, muscle aches, and physical discomfort.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Hormonal therapies, such as aromatase inhibitors (AI) and tamoxifen, significantly increase disease-free survival and reduce the risk of recurrence in breast cancer patients [1–3]. However, patients and survivors often experience unpleasant side effects from these therapies including musculoskeletal symptoms (joint pain and stiffness), bone loss, and menopausal symptoms [4]. Phase III trials, using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria, indicate that 18–35 % of breast cancer survivors experience musculoskeletal symptoms from AI [5–8]. Studies using survivor reports, however, found that 45–60 % of breast cancer survivors on AI complained of musculoskeletal symptoms [9–12]. Although musculoskeletal symptoms are not widely recognized as a common side effect of tamoxifen, up to 30 % of tamoxifen users report having these symptoms [13, 14]. Musculoskeletal symptoms are a major reason for non-compliance [15]; up to 25 % of users discontinue usage [16], representing the number one reason for discontinuation [17].

Unfortunately, musculoskeletal symptoms in breast cancer survivors on adjuvant hormone treatment are difficult to treat and no standard therapy exists. Survivors have reported achieving pain control with acetaminophen, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, glucosamine, and opiates [18]. However, there is a paucity of clinical trials demonstrating efficacy. The lack of effective treatments often leads to premature discontinuation, with non-adherence rates ranging between 20 and 40 % [15, 19, 20]. Furthermore, early discontinuation can reduce treatment efficacy and increase mortality [21].

Yoga is an increasingly prevalent form of exercise in the United States, and is already popular within the breast cancer community. Previous research is limited, but a one-arm trial found yoga reduced joint pain in women on AI [22], while another study demonstrated qualitative improvements in joint pain with the use of yoga [23], and a two-arm trial reported yoga participation reduced joint pain in breast cancer patients [24]. Additional studies have shown that yoga improves quality of life in breast cancer survivors, which may be due to reduced musculoskeletal symptoms. Research in non-cancer populations indicated yoga was effective at reducing arthritis pain, back pain, and carpal tunnel pain.

The primary aim of this study was to perform a secondary analysis from a previously published clinical trial to assess the efficacy of a standardized yoga intervention for improving musculoskeletal symptoms compared with standard care for post-treatment breast cancer survivors on hormonal therapy. We hypothesized that breast cancer survivors on hormonal therapy in the yoga condition would have a greater improvement in musculoskeletal symptoms than survivors in the standard care condition. Musculoskeletal symptoms were assessed using specific items from validated that specifically evaluated these symptoms. We also hypothesized that breast cancer survivors on AI would have a higher incidence and severity of musculoskeletal symptoms than tamoxifen users at baseline.

Methods

Study design

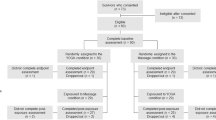

The full methods of the original RCT have been previously reported [25]. The University of Rochester Cancer Center (URCC) Community Clinical Oncology Program (CCOP) Research Base conducted a nationwide, multicenter, randomized clinical trial examining the efficacy of yoga for improving sleep quality in adult cancer survivors. Survivors were recruited in cohorts (N = 20–30) and randomized by CCOP location. Because the primary aim of the study was to examine the effect of yoga on sleep disturbance, randomization of each cohort was stratified by gender and baseline level of sleep disturbance (two levels: ≤5 or >5 on an 11-point symptom inventory scale anchored by “0” = no sleep disturbance and “10” = worst possible sleep disturbance). Group assignment was determined by a computer-generated random numbers table in blocks of two and an allocation ratio of 1:1.

The institutional review board at each site approved the study before any survivors were enrolled. All baseline measurements were completed during the week immediately prior to commencing the 4-week intervention (yoga or standard care), and all post measurements were completed during the week immediately following completion of the intervention. All demographic and clinical record information was obtained by the study coordinator at baseline. The sponsors had no role in study design or interpretation.

Study participants

Cancer survivors were recruited from 2007 to 2010 in 12 U.S. cities by nine CCOPs. Participants were enrolled between 2 and 24 months post surgery, chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy. For the original study, eligible survivors were required to (1) have a confirmed diagnosis of cancer; (2) have undergone and completed standard treatment for cancer; (3) have sleep disturbance (indicated by a response of 3 or greater on a clinical symptom inventory using an 11-point scale anchored by “0” = no sleep disturbance and “10” = worst possible sleep disturbance); (4) be able to read English; (5) be 21 years of age or older; (6) be able to give written informed consent; (7) not have maintained a regular personal practice of yoga within the 3 months prior to enrolling in the study or be planning to start yoga on their own during the time they are enrolled in the study; (8) not have a confirmed diagnosis of sleep apnea; (9) not be receiving any form of treatment for cancer, with the exception of hormonal or monoclonal antibody therapy; and (10) not have metastatic cancer. For the purpose of examining musculoskeletal symptoms, only breast cancer survivors currently receiving AI (N = 95) or TAM (N = 72) were included in this secondary analysis. All cancer survivors provided informed consent before completing any study requirements.

Yoga intervention experimental condition

The yoga intervention used the standardized Yoga for Cancer Survivors (YOCAS©®) program, designed by researchers at the University of Rochester Medical Center. The YOCAS©® intervention derives from two forms of yoga: gentle Hatha yoga and restorative yoga. The YOCAS©® sessions are standardized, and each session consists of physical alignment postures, breathing, and mindfulness exercises. Postures include 16 seated, standing, transitional, and supine poses. Breathing exercises include slow, controlled, diaphragmatic, and movement-coordinated breath work. Mindfulness exercises include meditation, visualization, and affirmation activities. The intervention is delivered in an instructor-taught, group format, twice a week for 75 min each time over 4 weeks for a total of eight sessions of yoga.

The YOCAS©® intervention was delivered by Yoga alliance registered instructors. To ensure intervention standardization, quality, fidelity, and prevention of drift, each yoga instructor completed a standardized training session and was provided with a detailed YOCAS©® instructor manual and DVD to keep for the duration of the trial. A study coordinator at each CCOP site also completed the same standardized training session as the yoga instructors and was provided with the same manual and DVD. The study coordinator at each CCOP site ensured drift did not occur and proper content was being taught by performed a random independent observation of YOCAS©® sessions. The YOCAS©® sessions were conducted in community-based group settings, free-of-charge to participants.

Standard care waitlist control condition

The control condition employed a standard care waitlist format. Cancer survivors assigned to this condition continued with the standard follow-up care provided by their treating oncologists as appropriate for their individual diagnoses. Participants in the control condition had the exact same contact time and attention from study staff as those in the experimental condition, except for the eight yoga sessions. Participants were offered the 4 weeks YOCAS©® program gratis after completing all study requirements.

Measures

Clinical and demographic information was collected by coordinators using medical records and study-specific forms. Race and ethnicity data were collected for descriptive purposes using the National Cancer Institute Cancer Therapy Reporting Program criteria for clinical trials (i.e., White, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, Asian, American Indian or Alaskan Native, Other, Hispanic or Latino, Non-Hispanic). Participants identified their race and ethnicity; categories were condensed to White, African American and other for reporting purposes. Adherence and compliance were monitored through the use of daily diaries and attendance records kept by the yoga instructors. No make-up sessions were provided for missed classes. Intensity of the yoga was monitored using the American College of Sports Medicine rating of perceived exertion scale (RPE) [26]. All participants were instructed to continue their routine daily activities during the 4-week intervention period, but were asked not to start a new yoga or exercise regimen on their own during this 4-week period to avoid exercise contamination in the trial design as much as possible.

Select questions from validated questionnaires were used to evaluate the effect of YOCAS on musculoskeletal symptoms, because this was not an a priori aim of the study. Questions were extracted from the University of Rochester Cancer Center Symptom Inventory (URCC SI), the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy with Fatigue Subscale (FACIT-F), and the Multidimensional Fatigue Symptom Inventory-Short Form (MFSI-SF). The specific question from the URCC SI is, “What is your level of pain over the last 7 days on a scale of 0 (pain not present) to 10 (as bad as you can imagine it could be)?” Specific statements used from the FACIT-F include, “I have pain,” “I feel ill,” “I have trouble finishing things because I’m tired,” and “I need help doing my usual activities,” which were rated on a 5-point scale (0 “not at all” to 4 “very much”). We also included the Physical Well-Being Subscore of the FACIT-F, which is the sum of responses to 7 questions (feeling ill, pain, lack of energy, nausea, bothered by side effects, forced to spend time in bed, and trouble meeting the needs of their family), with scores ranging from 0 to 28. It should be noted that the physical well-being subscore of the FACIT-F is scored in reverse, with 0 being the worst possible score and 28 being the best. Specific questions from the MFSI-SF include, “My muscles ache,” “My legs feel weak,” “My arms feel weak,” “My head feels heavy,” “My body feels heavy all over,” and “I ache all over,” which were rated on a 5-point scale (0 “not at all” to 4 “very much”). We also included the physical dimension subscore of the MFSI-SF, which is the sum of the score to the previous 6 questions, with scores ranging from 0 to 24 (higher scores denote reduced physical well-being).

Statistical analyses

Clinical and demographic variables were examined with two-tailed (α = 0.05) t tests for continuous variables and Chi-square tests for categorical variables to test population differences in the two arms. An analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), with arm as the factor, baseline as the covariate, and arm by baseline interaction, was used to evaluate arm effects for the post-treatment musculoskeletal symptom scores. If the interaction showed a trend toward significance (P ≤ 0.10), it was retained in the model. Estimated within-group effects from the ANCOVAs were expressed in terms of pre-post mean differences. Binary logistic regression, with arm as the independent variable, was used to evaluate arm effects for the reduction in musculoskeletal symptoms. The logistic regression analyses were restricted to those with at least moderate muscle and/or body aches at baseline (a score of ≥2 on a 0–4 scale). This restriction was made to allow for survivors to have an improvement (i.e., a decrease in score) over the course of the study. Based on the pre/post change, participants for this analysis were categorized into two categories for the dependent variable: (1) decreased musculoskeletal symptoms or (2) increased/no change in musculoskeletal symptoms. All data were analyzed using the intent-to-treat principle.

Results

In the current study, 167 survivors were currently on some form of endocrine therapy; 72 were on tamoxifen and 95 were on AI. Table 1 shows the overall demographics of the sample and the demographic characteristics by randomized arm assignment. There were no significant differences between the two arms except for more non-Caucasians in the control arm and a longer period since cancer treatment in the yoga arm. Table 2 shows the demographic characteristics by type of endocrine therapy. As expected, women on AI were significantly older than women on tamoxifen. There were no other differences noted between the different endocrine therapies.

Table 3 shows the baseline musculoskeletal symptom averages by type of endocrine therapy. In general, women on AI had a higher musculoskeletal symptom burden than women on tamoxifen. AI users reported significantly greater levels of pain, muscle aches, feeling ill, needing help doing usual activities, and a feeling of heaviness in the head and body than tamoxifen users. AI users also had significantly lower physical subscores on both the MFSI-SF and FACIT-F than tamoxifen users.

The change in musculoskeletal symptoms for women on endocrine therapy from baseline to post-intervention by arm is shown in Table 4. There were significantly greater improvements in the yoga group compared to the control group for both physical subscores (P′S < 0.05). Additionally, women in the yoga group had significantly greater reductions in the levels of pain, muscle aches, needing help finishing activities, time spent in bed, and feelings of heaviness in the body than the control group.

Table 5 shows the percentage improvement and adjusted odds ratios with corresponding 95 % CI for musculoskeletal symptoms by group. For pain, muscle aches, and body aches, we included only those who reported moderate to severe levels at baseline (a score of ≥2 on a 0–4 scale). A significantly greater proportion of yoga participants than control participants had reductions in total body aches (yoga = 88.0 % vs. control 56.7 %; P = 0.02; ORadj = 2.19; 95 % CI 1.10–4.36), while there was a significant trend for pain (yoga = 57.1 % vs. control 37.1 %; P = 0.09; ORadj = 3.51; 95 % CI 1.17–10.47), and no significant reduction for muscle aches (yoga = 60.4 % vs. control 51.4 %; P = 0.35; ORadj = 1.41; 95 % CI 0.61–3.27). There was also a significant improvement in the FACIT physical subscore (yoga = 78.9 % vs. control 60.0 %; P = 0.01; ORadj = 2.47; 95 % CI 1.17–5.23) and a significant trend toward improvement in the MFSI physical subscore (yoga = 66.2 % vs. control 52.9 %; P = 0.09; ORadj = 1.78; 95 % CI 0.91–3.48) for the yoga group.

Discussion

This secondary data analysis found breast cancer survivors on endocrine therapy had a high musculoskeletal symptoms burden, with women on AI having a greater musculoskeletal burden than women on tamoxifen at baseline. The main finding of this analysis showed YOCAS yoga was effective at reducing musculoskeletal symptoms for breast cancer survivors on endocrine therapy. Yoga participants demonstrated significantly greater improvements in pain, muscle aches, body aches, and other musculoskeletal measures at post-intervention compared with standard care participants. The majority of yoga participants with moderate to severe musculoskeletal symptoms at baseline reported decreases in severity, with up to 88 % reporting reduced musculoskeletal symptom severity. Furthermore, participants in the yoga group had significant improvements in the physical subscores from the FACIT-F and MFSI-SF. The results from this study confirm the findings of the small number of studies that show yoga may be an effective intervention for musculoskeletal symptoms in breast cancer survivors. The results of this study are not intended to provide a basis for practice recommendations, but rather to provide the scientific rationale for a yoga trial that specifically focuses on musculoskeletal symptoms in breast cancer survivors on endocrine therapy.

This is the first 2-arm RCT to report the quantitative effect of yoga on musculoskeletal symptoms among breast cancer survivors on endocrine therapy. Of the only two studies that examined the effect of yoga on musculoskeletal symptoms in breast cancer survivors, one performed a qualitative analysis while the other study was a one-arm trial with pre/post measurements. Furthermore, this trial included a total of 167 women, compared to the other trials, which only included 10 breast cancer survivors. The 167 women were enrolled from sites across the United States, making the results generalizable to breast cancer survivors in the U.S.

While the results of this study are encouraging, a number of limitations should be considered when interpreting the results. First and foremost, the original RCT was designed to test the effect of yoga on sleep quality in all cancer survivors. There was no a priori aim in the study to examine the effect of yoga of musculoskeletal symptoms in breast cancer survivors on endocrine therapy. For this reason, questionnaires designed to specifically measure musculoskeletal symptoms, such as the brief pain inventory or Health Assessment Questionnaire II, were not used in this study. Therefore, the assessment of musculoskeletal symptoms was limited to single item self-report measures from the MFSI-SF and FACIT-F. The use of valid and reliable questionnaires, such as the BPI and HAQ-II, will be needed in future studies to determine the true impact of yoga on musculoskeletal symptoms. Lastly, there were no long-term follow-ups to assess the sustainability of benefits from YOCAS.

In conclusion, this is one of the first studies to show that yoga, specifically the Gentle Hatha and Restorative yoga components in the YOCAS program, may be an effective intervention for the treatment of musculoskeletal symptoms in breast cancer survivors on endocrine therapy. Clinical trials whose primary hypothesis focuses on musculoskeletal symptoms such as arthralgias and myalgias are needed to confirm these findings. The YOCAS yoga program used in this study was designed to be reproduced and could be used in any future trials. Future studies should also seek to examine the sustainability of any benefits achieved during the active portion of the intervention and the biological mechanisms by which yoga reduces musculoskeletal symptoms.

References

Regan MM, Neven P, Giobbie-Hurder A, Goldhirsch A, Ejlertsen B, Mauriac L, Forbes JF, Smith I, Lang I, Wardley A et al (2011) Assessment of letrozole and tamoxifen alone and in sequence for postmenopausal women with steroid hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: the BIG 1-98 randomised clinical trial at 8.1 years median follow-up. Lancet Oncol 12:1101–1108. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70270-4

Arimidex TAoiCTG, Forbes JF, Cuzick J, Buzdar A, Howell A, JS Tobias, Baum M (2008) Effect of anastrozole and tamoxifen as adjuvant treatment for early-stage breast cancer: 100 month analysis of the ATAC trial. Lancet Oncol 9:45–53. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70385-6

International Breast Cancer Study G, Group BIGC, Regan MM, Price KN, Giobbie-Hurder A, Thurlimann B, Gelber RD (2011) Interpreting breast international group (big) 1-98: a randomized, double-blind, phase iii trial comparing letrozole and tamoxifen as adjuvant endocrine therapy for postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive, early breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 13:209. doi:10.1186/bcr2837

Mouridsen HT (2006) Incidence and management of side effects associated with aromatase inhibitors in the adjuvant treatment of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. Curr Med Res Opin 22:1609–1621. doi:10.1185/030079906X115667

Baum M, Buzdar A, Cuzick J, Forbes J, Houghton J, Howell A, Sahmoud T (2003) Anastrozole alone or in combination with tamoxifen versus tamoxifen alone for adjuvant treatment of postmenopausal women with early-stage breast cancer: results of the ATAC (Arimidex, Tamoxifen Alone or in Combination) trial efficacy and safety update analyses. Cancer 98:1802–1810

Buzdar A, Howell A, Cuzick J, Wale C, Distler W, Hoctin-Boes G, Houghton J, Locker GY, Nabholtz JM (2006) Comprehensive side-effect profile of anastrozole and tamoxifen as adjuvant treatment for early-stage breast cancer: long-term safety analysis of the ATAC trial. Lancet Oncol 7:633–643. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70767-7

Coates AS, Keshaviah A, Thurlimann B, Mouridsen H, Mauriac L, Forbes JF, Paridaens R, Castiglione-Gertsch M, Gelber RD, Colleoni M et al (2007) Five years of letrozole compared with tamoxifen as initial adjuvant therapy for postmenopausal women with endocrine-responsive early breast cancer: update of study BIG 1-98. J Clin Oncol 25:486–492. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.08.8617

Mouridsen H, Giobbie-Hurder A, Goldhirsch A, Thurlimann B, Paridaens R, Smith I, Mauriac L, Forbes JF, Price KN, Regan MM et al (2009) Letrozole therapy alone or in sequence with tamoxifen in women with breast cancer. N Engl J Med 361:766–776. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0810818

Crew KD, Greenlee H, Capodice J, Raptis G, Brafman L, Fuentes D, Sierra A, Hershman DL (2007) Prevalence of joint symptoms in postmenopausal women taking aromatase inhibitors for early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 25:3877–3883. doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.10.7573

Mao JJ, Stricker C, Bruner D, Xie S, Bowman MA, Farrar JT, Greene BT, DeMichele A (2009) Patterns and risk factors associated with aromatase inhibitor-related arthralgia among breast cancer survivors. Cancer 115:3631–3639. doi:10.1002/cncr.24419

Henry NL, Giles JT, Ang D, Mohan M, Dadabhoy D, Robarge J, Hayden J, Lemler S, Shahverdi K, Powers P et al (2008) Prospective characterization of musculoskeletal symptoms in early stage breast cancer patients treated with aromatase inhibitors. Breast Cancer Res Treat 111:365–372. doi:10.1007/s10549-007-9774-6

Oberguggenberger A, Hubalek M, Sztankay M, Meraner V, Beer B, Oberacher H, Giesinger J, Kemmler G, Egle D, Gamper EM et al (2011) Is the toxicity of adjuvant aromatase inhibitor therapy underestimated? Complementary information from patient-reported outcomes (PROs). Breast Cancer Res Treat 128:553–561. doi:10.1007/s10549-011-1378-5

Group AT, Sestak I, Cuzick J, Sapunar F, Eastell R, Forbes JF, Bianco AR, Buzdar AU (2008) Risk factors for joint symptoms in patients enrolled in the ATAC trial: a retrospective, exploratory analysis. Lancet Oncol 9:866–872. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70182-7

Blencowe NS, Reichl C, Gahir J, Paterson I (2010) The use of Nolvadex in the treatment of generic tamoxifen-associated small joint arthralgia. Breast 19:243–245. doi:10.1016/j.breast.2010.02.004

Partridge AH, LaFountain A, Mayer E, Taylor BS, Winer E, Asnis-Alibozek A (2008) Adherence to initial adjuvant anastrozole therapy among women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 26:556–562. doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.11.5451

Dent S, DiValentin T, Vandermeer L, Spaans J, Verma S (2006) Long term toxicities in women with early stage breast cancer treated with aromatase inhibitors: data from a tertiary care center. Breast Cancer Res Treat 100(suppl 1):S190

Fontaine C, Meulemans A, Huizing M, Collen C, Kaufman L, De Mey J, Bourgain C, Verfaillie G, Lamote J, Sacre R et al (2008) Tolerance of adjuvant letrozole outside of clinical trials. Breast 17:376–381. doi:10.1016/j.breast.2008.02.006

Presant CA, Bosserman L, Young T, Vakil M, Horns R, Upadhyaya G, Ebrahimi B, Yeon C, Howard F (2007) Aromatase inhibitor-associated arthralgia and/or bone pain: frequency and characterization in non-clinical trial patients. Clin Breast Cancer 7:775–778. doi:10.3816/CBC.2007.n.038

Hershman DL, Shao T, Kushi LH, Buono D, Tsai WY, Fehrenbacher L, Kwan M, Gomez SL, Neugut AI (2011) Early discontinuation and non-adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy are associated with increased mortality in women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 126:529–537. doi:10.1007/s10549-010-1132-4

Ziller V, Kalder M, Albert US, Holzhauer W, Ziller M, Wagner U, Hadji P (2009) Adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy in postmenopausal women with breast cancer. Ann oncol 20:431–436. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdn646

McCowan C, Shearer J, Donnan PT, Dewar JA, Crilly M, Thompson AM, Fahey TP (2008) Cohort study examining tamoxifen adherence and its relationship to mortality in women with breast cancer. Br J Cancer 99:1763–1768. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6604758

Ulger O, Yagli NV (2010) Effects of yoga on the quality of life in cancer patients. Complement Ther Clin Pract 16:60–63. doi:10.1016/j.ctcp.2009.10.007

Galantino ML, Greene L, Archetto B, Baumgartner M, Hassall P, Murphy JK, Umstetter J, Desai K (2012) A qualitative exploration of the impact of yoga on breast cancer survivors with aromatase inhibitor-associated arthralgias. Explore: J Sci Heal 8:40–47. doi:10.1016/j.explore.2011.10.002

Carson JW, Carson KM, Porter LS, Keefe FJ, Seewaldt VL (2009) Yoga of awareness program for menopausal symptoms in breast cancer survivors: results from a randomized trial. Support Care Cancer : Offic J Multinatl Assoc Suppor Care Cancer 17:1301–1309. doi:10.1007/s00520-009-0587-5

Mustian KM, Sprod LK, Janelsins M, Peppone LJ, Palesh OG, Chandwani K, Reddy PS, Melnik MK, Heckler C, Morrow GR (2013) Multicenter, randomized controlled trial of yoga for sleep quality among cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.43.7707

American College of Sports M (2010) ACSM’s Guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore

Acknowledgments

We thank Susan Rosenthal, MD, for her support on this project. We extend special thanks to the cancer survivors, yoga instructors, and research staff in the University of Rochester Community Clinical Oncology Program (CCOP) Research Base and at each of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) CCOP affiliates who recruited and followed participants in this study. We thank the NCI and the Office of Cancer Complementary and Alternative Medicine for their funding support of this project.

Conflicts of interest

The authors indicate no potential conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Peppone, L.J., Janelsins, M.C., Kamen, C. et al. The effect of YOCAS©® yoga for musculoskeletal symptoms among breast cancer survivors on hormonal therapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat 150, 597–604 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-015-3351-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-015-3351-1