Abstract

Factors associated with suicidal ideation in the gender dysphoria population are not completely understood. This high-risk population is more likely to suffer stressful events such as assault or employment discrimination. This study aimed to determine the association of stressful events and social support on suicidal ideation in gender dysphoria and to analyze the moderator effect of social support in relation to stressful events and suicidal ideation. A cross-sectional design was used in a clinical sample attending a public gender identity unit in Spain that consisted of 204 individuals (51.7% birth-assigned males and 48.3% birth-assigned females), aged between 13 and 59 (M = 27.95 years, SD = 9.58). A Structured Clinical Interview, a list of 16 stressful events, and a functional social support questionnaire (Duke-UNC-11) were used during the initial visits to the unit. The data were collected between 2011 and 2012. A total of 50.1% of the sample have had suicidal ideation. The following stressful events were associated with suicidal ideation: homelessness, eviction from home, and having suffered from physical or verbal aggression. Also, there was an inverse relation between perceived social support and suicidal ideation. There was a statistically significant interaction between a specific stressful event (eviction) and perceived social support. The study suggests that the promotion of safer environments could be related to lower suicidal ideation and that networks that provide social support could buffer the association between specific stressful events and suicidal ideation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The high risk of suicidal behavior is a significant problem for those who have gender dysphoria (Fitzpatrick et al., 2005; Lobato et al., 2007; Zucker et al., 2016), with approximately one out of three adults with this condition having experienced suicidal behavior. The prevalence of suicide attempts in this population is elevated in comparison with non-gender dysphoric individuals (Boza & Nicholson Perry, 2014; Bradford et al., 2013; Bolger et al., 2014; Grant et al., 2011; Guzmán-Parra et al., 2016; Haas et al., 2014; Nuttbrock et al., 2010; Peterson et al., 2017), and it remains high even after sex reassignment surgery (Dhejne et al., 2011). Also, death by suicide is higher than expected in the transgender population undergoing hormone treatment (de Blok et al., 2021).

It is well-established such as suicidal ideation is an important risk factor for suicide attempts in gender dysphoria (Nock et al., 2008). The prevalence of suicidal behavior in people suffering gender dysphoria is higher than in the general population; for example, one study found a prevalence of 53% in current ideation (Kim et al., 2006) and different studies between 50 and 73.6% in lifetime ideation (Guzmán-Parra et al., 2016; Hoshiai et al., 2010; Modrego Pardo et al., 2021; Terada et al., 2011). This rate of lifetime prevalence of suicide ideation is comparable to the rates found in people at ultra-high risk of psychosis (66.0%) (Taylor et al., 2015), and with major depressive disorder (53.1%) (Cai et al., 2021). Moreover, one study found characteristics feature in a sample of non-binary psychiatric inpatient individuals with suicidal ideation in comparison with control psychiatric inpatients with suicidal ideation (Zinchuk et al., 2022).

There are different possible explanations for the high prevalence of suicidality in the gender dysphoria population. For example, one hypothesis is that a “primary” mental disorder could influence the presence of gender dysphoria or that gender dysphoria is inherently distressing (Zucker, 2019). However, nowadays the most common and accepted model to explain the high prevalence of suicidality is based on minority stress suffered by this population. According to the minority stress model (Meyer, 2003), recently adapted to the transgender and gender nonconforming population (Hendricks & Testa, 2012), the transgender population is frequently victim of many external factors (intra-familial and extra-familial factors) such as stressful events, including physical and sexual violence, discrimination, victimization, harassment, poverty, rejection, exclusion, and trauma (Bauer et al., 2015; Clements-Nolle et al., 2006; Goldblum et al., 2012). This may be related to individual knowledge, perception, or identification with the minority status, which consequently leads to expectations of rejection, concealment of one’s own gender identity, and internalized transphobia (Hendricks & Testa, 2012; Meyer, 2003).

The minority stress model had been combined with the interpersonal theory of suicide to explain the relationship between minority stress and suicide behavior (Joiner, 2021; Testa et al., 2017). Negative mental health effects, such as a high number of symptoms of depression, anxiety, personality problems, and especially suicide behaviors and ideation (Guzmán-Parra et al., 2016; Heylens et al., 2014; Khobzi Rotondi, 2012), may be the consequence of stress experienced by transgender people (Nemoto et al., 2011). Recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses support the association between internal and external minority stress and suicidal ideation in the transgender population and have summarized the different factors and effect sizes associated with suicidal ideation (Gosling et al., 2022; Pellicane & Ciesla, 2022). In summary, various demographic factors, e.g., age, the stage of transition (Terada et al., 2011); external factors, e.g., physical violence, sexual abuse (Goldblum et al., 2012); internal factors, e.g., perceived prejudice and discrimination, enacted and internal stigma (Bauer et al., 2015; Clements-Nolle et al., 2006; Inderbinen et al., 2021); and mental health issues, e.g., impulsivity and sensation seeking (Liu & Mustanski, 2012) have been associated with suicidability in gender non-conforming population.

However, more evidence is still needed on the relationship between specific factors related to stress and the presence of high rates of mental disorders and suicidality in the gender dysphoria population. Furthermore, there are protective factors that minimize the impact of stressful events on this population, and these factors may moderate the negative effects of stress. In one study, family and peer support, as well as pride in one’s identity, were all inversely associated with psychological distress, suggesting that these are protective factors in gender dysphoria (Nemoto et al., 2011). In another study, peer support significantly moderated the relationship between enacted stigma and psychological distress, thus emerging as a resilience factor in the face of actual discriminatory experiences (Bockting et al., 2013). Moreover, social support and positive events synergistically buffered the relationship between negative events and suicidal ideation (Kleiman et al., 2014). Also, a lower perceived social support from their immediate family in comparison with their non-transgender siblings (Factor & Rothblum, 2007), and less social support from biological family members was observed (Nemoto et al., 2011). Furthermore, it has been shown that transgender individuals with a history of suicidal ideation had expressed higher need for social support (Nemoto et al., 2011). In addition, parental support for gender identity has been associated with reduced suicidal ideation among transgender individuals (Bauer et al., 2015). Moreover, a previous study conducted in Spain had shown that greater perceived family support was related to a better perceived physical, psychological, social, and environmental well-being of gender dysphoric individuals (Gómez-Gil et al., 2013).

Despite this, limited published data exist regarding the relation of stress factors or social support with suicidal ideation in the clinical gender dysphoric population. The main objective of this study was to examine the role and interaction of stressful events and perceived social support on suicidal thoughts in a clinical sample of gender dysphoric individuals.

Method

Participants and Procedure

This study was part of an ongoing project initiated in the year 2000: “Transsexualism in Andalusia: Psychiatric, endocrine and surgical morbidity and evaluation of the therapeutic intervention process: Experiences of the first reference unit in Spain.” The study was approved by the hospital ethics committee. The evaluations were conducted in 2011–2012 by clinical psychologists trained in patient diagnosis and evaluation, and also in the administration of the research instruments used for the study.

The sample consisted of 204 patients attending the Transsexual and Gender Identity Unit (TGIU) at the University Regional Hospital of Málaga (51.7% trans women and 48.3% trans men), aged between 13 and 59 (M = 27.95 years, SD = 9.58, 15 participants under 18 years). In trans women, 86.7% were androphilic, 9.5% gynephilic, 2.9% biphilic and 1% asexual. In trans men, 93.9% were gynephilic, 3% androphilic, 2% biphilic and 1% asexual. A consecutive series of participants were invited to participate in this study from those being assessed or treated at the hospital TGIU. The only inclusion criteria were to have a diagnosis of gender dysphoria in accordance with the CIE-10 (World Health Organization, 2010) as assessed by a clinical psychologist. The exclusion criteria to be treated in the TGIU were to have a diagnosis of psychotic disorders or severe personality disorders that could interfere with the treatment according to the clinical criteria of a psychologist. Approximately, 7.8% of users were excluded at the TGIU for those exclusion criteria. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study, and parents also signed the informed consent for participants under the age of 18. There was a total of 242 eligible patients during the study period, 18 (7.4%) did not meet the inclusion criteria, 19 (7.8%) did not complete the assessment, and one (0.4%) refused to participate in the study.

Measures

Structured clinical interview. This specific instrument was designed at the TGIU and was administered to collect demographic and clinical data. It was used to collect the following variables: (1) sociodemographic information: age, gender, civil status, education, and employment status; (2) lifetime suicidal ideation. The presence of suicidal ideation was assessed with the following question: “Have you ever felt so sad that you thought of committing suicide?”.

Stressful life events were assessed using a list of 16 stressful life events (see Table 2).

The Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire. The DUKE-UNC (Broadhead et al., 1988) evaluates perceived social support with 11 items using a 5-point Likert scale (Table 3). The scale ranges from “much less than I would like” to “as much as I would like.” We used the Spanish version of the scale (Bellón Saameño et al., 1996). In our sample, the scale had good internal consistency (Cronbach’s a = 0.90).

Statistical Analysis

Two groups were established based on the presence of lifetime suicidal ideation. Sociodemographic information was analyzed with the chi-square test as all the variables were categorical. To analyze the association between stressful events and perceived social support with suicidal ideation, bivariate and multivariate analyses using logistic regression were carried out. In the multivariate analysis, age, gender, and occupational status were used as possible confounding factors. To test the moderator effect of perceived social support on the association between stressful events and suicidal ideation, the procedure devised by Baron and Kenny (1986) was used. We tested the moderator effect of perceived suicidal support on stressful events that were statistically significantly associated with suicidal ideation (p < 0.05). The statistical analyses were performed using version 15.0 of the SPSS statistical software package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

A total of 50.1% of individuals in the studied population expressed lifetime suicidal ideation. The results of the comparative analysis found no significant differences between groups in gender, age, educational level, marital status, occupational status, and sexual orientation (Table 1).

The most frequent stressful events in the sample were to be the object of physical or verbal aggression (80.9%) and the death of a relative (71%). The least frequent events were the death of the partner (2.5%) and incarceration (4.4%). Different stressful events were associated with suicidal ideation reaching a significant level of confidence: loss of home (OR = 7.00; p = 0.012), eviction (OR = 2.41; p = 0.032), and being the object of physical or verbal aggression (OR = 2.46; p = 0.016). In the multivariate logistic regression models adjusted by gender, age, and occupational status, the same stressful events maintained a significant level of confidence: loss of home (AOR = 7.57; p = 0.010), eviction (AOR = 2.56; p = 0.024), and to be the object of aggression (AOR = 2.37; p = 0.026). The information regarding stressful events is summarized in Table 2.

Perceived social support (M = 43.49; SD = 9.80; range = 14–55) was significantly associated with the presence of suicidal ideation (OR = 0.95; p = 0.002) and was also adjusted for possible confounders (AOR = 0.95; p = 0.001). The DUKE-UNC-11 items significantly associated with suicidal ideation were: “I receive help on home-related issues” (OR = 0.79, p = 0.018; AOR = 0.75, p = 0.007), “I have people who care about what happens to me” (AOR = 0.73, p = 0.025), “I receive love and affection” (OR = 0.73, p = 0.008; AOR = 0.70, p = 0.004), “I have the chance to talk about my problems at work/home with somebody” (OR = 0.65, p < 0.001; AOR = 0.63, p < 0.001), “I have a chance to talk about my personal and family problems with somebody” (OR = 0.71, p = 0.005; AOR = 0.69, p = 0.004), “I’m able to talk about my economic problems with somebody” (OR = 0.78, p = 0.031; AOR = 0.75, p = 0.020), “I receive useful advice when something important happens in my life” (OR = 0.76, p = 0.033; AOR = 0.76, p = 0.030), and “I receive assistance when I am sick” (AOR = 0.76, p = 0.039). The information about perceived social support is summarized in Table 3.

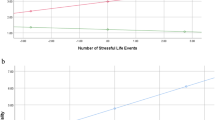

The moderator effect of perceived social support on stressful events was statistically significant only in the case of eviction from home (p = 0.046). The information regarding interaction effects in this population is summarized in Table 4.

Discussion

This study examined the associations and interactions between suicidal ideation, stressful events, and perceived social support in a clinical sample with gender dysphoria. We found that selective stressful events (loss of home, eviction, and being the object of aggression) and perceived social support were associated with suicidal ideation. Moreover, we also found a moderation effect of perceived social support for a stressful event regarding suicidal ideation, specifically eviction from the home.

Previous studies have shown that some stressful events (e.g., suffering physical and sexual violence, discrimination, or trauma) were related to suicidal behavior in the trans population (Bauer et al., 2015; Clements-Nolle et al., 2006). The above-mentioned stresses could be conceptualized as minority stressful events connected with unobvious sex, putting this population at special risk (Factor & Rothblum, 2007). In light of all revised data, there are factors such as a large prevalence of aggression, increased violence, harassment, and discrimination toward nonconforming gender people that may affect their mental health (Carter et al., 2019; Cogan et al., 2021; Guzman-Parra et al., 2014; Lelutiu-Weinberger et al., 2020; Rabasco & Andover, 2021; Testa et al., 2012). Institutions should make an effort to create and implement preventive programs and safe environments for the gender dysphoric population (Meyer, 2014; Vaughan & Rodriguez, 2014).

The group without suicidal thoughts was characterized by a significantly higher score of perceived social support. The most significant item was the possibility to talk to someone at work or home about problems. The results of our study concerning social support can be discussed mostly in the light of data from transgender and gender non-conforming samples. Recent research suggests that social support is a protective factor against suicide ideation and suicidal behavior in the gender non-conforming population (Bauer et al., 2015; Romanelli & Lindsey, 2020; Treharne et al., 2020). Specifically, community connectedness (Rabasco & Andover, 2021) and support (Shah et al., 2018), family and friend support (Carter et al., 2019; Moody & Smith, 2013), and partner support (Kota et al., 2020) have been negatively associated with suicidal ideation. However, one study did not found an association between access to trans support groups and suicidal attempts (Zwickl et al., 2021). Transgender individuals received less social support from within the family in comparison with their non-trans siblings, whereas no significant difference was found in experiencing social support from friends (Factor & Rothblum, 2007). Difficulties with obtaining support from significant relatives may partly explain the high suicidal ideation rates among transgenders (Clements-Nolle et al., 2006), and our study is in accordance with previous results in clinical samples with a diagnosis of gender dysphoria. It has also been emphasized that social support is needed especially during sexual reassignment transition (Budge et al., 2012). Our study demonstrates that persons who report that they can talk about their different problems also report less suicidal ideation. These results revealed the importance of a social network outside the family and highlights the influence of the community and friends. Social inclusion (social support, gender-specific support from parents, and identity documents), protection from transphobia (interpersonal and violence), and undergoing medical transition have the potential for sizeable effects on the high rates of suicidal ideation and attempts in transgender communities (Bauer et al., 2015).

According to our findings, social support could play a relevant role in moderating, at least in part, the effects of stressful events on suicidal ideation. One study found that family and friend support did not moderate the association between discrimination and suicidal ideation; however, a significant moderation effect of trans friends’ support and connection with LGTB people and veterans was found (Carter et al., 2019). Specifically, general social support could be important as a buffer between socioeconomic problems and suicidal ideation. Moderating the effect of social support in stressful events over suicidal ideation also stands in line with the minority stress model as social support is a protective factor, which attenuates the effects of stressors on suicidal ideation. Ensuring social support for transgender individuals may promote better mental health and is a low-cost strategy with high payoffs (Snapp et al., 2015).

Limitations

This research had some limitations. The hospital sample was not representative of the whole population with gender dysphoria, as an unknown proportion of these individuals did not actively seek sex reassignment surgery, and therefore, these individuals did not visit the TGIU. The exclusion criteria for the treatment in the unit could influence the underestimation of the results. It is probable that other variables are associated with suicidal ideation that have not been taken into consideration and would be important in a study of this nature. There is no control group from the general population. Moreover, since this is a cross-sectional study, a causal relationship between variables cannot be established, nor with the factors involved in the etiology of suicidal ideation in this specific clinical population. Future studies should use a more diverse and larger sample to increase the generalizability of the results. We also recommend investigating whether these findings can be replicated in other cultures and nationalities. Another limitation is the relatively poor measure of suicidal ideation based on the question done to the participants.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we can state that the results of our study support our first hypothesis concerning the presence of stressful events associated with suicidal thoughts and identified protective and risk factors for suicidal ideation in a clinical population with gender dysphoria. Moreover, it identified the moderating effects played by social support in the relationship between stressful events on suicidal ideation. Despite the limitations, the study provides support for a model in which social support acts as a moderator of the relationship between specific stressful life events and suicidal ideation.

References

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research. Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

Bauer, G. R., Scheim, A. I., Pyne, J., Travers, R., & Hammond, R. (2015). Intervenable factors associated with suicide risk in transgender persons: A respondent driven sampling study in Ontario, Canada. BMC Public Health, 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1867-2

Bockting, W. O., Miner, M. H., Swinburne Romine, R. E., Hamilton, A., & Coleman, E. (2013). Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the US transgender population. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 943–951. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301241

Bolger, A., Jones, T., Dunstan, D., & Lykins, A. (2014). Australian trans men: Development, sexuality, and mental health. Australian Psychologist, 49(6), 395–402. https://doi.org/10.1111/ap.12094

Boza, C., & Nicholson Perry, K. (2014). Gender-related victimization, perceived social support, and predictors of depression among transgender Australians. International Journal of Transgenderism, 15(1), 35–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2014.890558

Bradford, J., Reisner, S. L., Honnold, J., & a, & Xavier, J. (2013). Experiences of transgender-related discrimination and implications for health: Results from the Virginia Transgender Health Initiative Study. American Journal of Public Health, 103(10), 1820–1829. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.300796

Broadhead, W. E., Gehlbach, S. H., de Gruy, F. V., & Kaplan, B. H. (1988). The Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire. Measurement of social support in family medicine patients. Medical Care, 26(7), 709–723.

Budge, S. L., Katz-Wise, S. L., Tebbe, E. N., Howard, K. A. S., Schneider, C. L., & Rodriguez, A. (2012). Transgender emotional and coping processes: Facilitative and avoidant coping throughout gender transitioning. The Counseling Psychologist, 41(4), 601–647. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000011432753

Cai, H., Jin, Y., Liu, S., Zhang, Q., Zhang, L., Cheung, T., Balbuena, L., & Xiang, Y. T. (2021). Prevalence of suicidal ideation and planning in patients with major depressive disorder: A meta-analysis of observation studies. Journal of Affective Disorders, 293, 148–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.05.115

Carter, S. P., Allred, K. M., Tucker, R. P., Simpson, T. L., Shipherd, J. C., & Lehavot, K. (2019). Discrimination and suicidal ideation among transgender veterans: The role of social support and connection. LGBT Health, 6(2), 43–50. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2018.0239

Clements-Nolle, K., Marx, R., & Katz, M. (2006). Attempted suicide among transgender persons: The influence of gender-based discrimination and victimization. Journal of Homosexuality, 51(3), 53–69. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v51n03_04

Cogan, C. M., Scholl, J. A., Lee, J. Y., Cole, H. E., & Davis, J. L. (2021). Sexual violence and suicide risk in the transgender population: The mediating role of proximal stressors. Psychology and Sexuality, 12(1–2), 129–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2020.1729847

de Blok, C. J., Wiepjes, C. M., van Velzen, D. M., Staphorsius, A. S., Nota, N. M., Gooren, L. J., Kreukels, B. P., & den Heijer, M. (2021). Mortality trends over five decades in adult transgender people receiving hormone treatment: A report from the Amsterdam cohort of gender dysphoria. The Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology, 9(10), 663–670. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(21)00185-6

Dhejne, C., Lichtenstein, P., Boman, M., Johansson, A. L. V., Långström, N., & Landén, M. (2011). Long-term follow-up of transsexual persons undergoing sex reassignment surgery: Cohort study in Sweden. PLoS ONE, 6(2), e16885. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0016885

Factor, R. J., & Rothblum, E. D. (2007). A study of transgender adults and their non-transgender siblings on demographic characteristics, social support, and experiences of violence. Journal of LGBT Health Research, 3(3), 11–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/15574090802092879

Fitzpatrick, K. K., Euton, S. J., Jones, J. N., & Schmidt, N. B. (2005). Gender role, sexual orientation and suicide risk. Journal of Affective Disorders, 87(1), 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2005.02.020

Goldblum, P., Testa, R. J., Pflum, S., Hendricks, M. L., Bradford, J., & Bongar, B. (2012). The relationship between gender-based victimization and suicide attempts in transgender people. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 43(5), 468–475. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029605

Gómez-Gil, E., Zubiaurre-Elorza, L., Esteva de Antonio, I., Guillamon, A., & Salamero, M. (2014). Determinants of quality of life in Spanish transsexuals attending a gender unit before genital sex reassignment surgery. Quality of Life Research, 23, 669–676. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-013-0497-3

Gosling, H., Pratt, D., Montgomery, H., & Lea, J. (2022). The relationship between minority stress factors and suicidal ideation and behaviours amongst transgender and gender non-conforming adults: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 303(15), 31–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.12.091

Grant, J. E., Flynn, M., Odlaug, B. L., & Schreiber, L. R. N. (2011). Personality disorders in gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender chemically dependent patients. American Journal on Addictions, 20(5), 405–411. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1521-0391.2011.00155.x

Guzman-Parra, J., Paulino-Matos, P., de Diego-Otero, Y., Perez-Costillas, L., Villena-Jimena, A., Garcia-Encinas, M. A., & Bergero-Miguel, T. (2014). Substance use and social anxiety in transsexual individuals. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 10(3), 162–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/15504263.2014.930658

Guzmán-Parra, J., Sánchez-Álvarez, N., de Diego-Otero, Y., Pérez-Costillas, L., Esteva de Antonio, I., Navais-Barranco, M., Castro-Zamudio, S., & Bergero-Miguel, T. (2016). Sociodemographic characteristics and psychological adjustment among transsexuals in Spain. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(3), 587–596. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0557-6

Haas, A. P., Rodgers, P. L., & Herman, J. L. (2014). Suicide attempts among transgender and gender non-conforming adults. Work, 50, 59.

Hendricks, M. L., & Testa, R. J. (2012). A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: An adaptation of the minority stress model. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 43(5), 460–467. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029597

Heylens, G., Verroken, C., De Cock, S., T’Sjoen, G., & De Cuypere, G. (2014). Effects of different steps in gender reassignment therapy on psychopathology: A prospective study of persons with a gender identity disorder. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 11(1), 119–126. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12363

Hoshiai, M., Matsumoto, Y., Sato, T., Ohnishi, M., Okabe, N., Kishimoto, Y., Terada, S., & Kuroda, S. (2010). Psychiatric comorbidity among patients with gender identity disorder. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 64(5), 514–519. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1819.2010.02118.x

Inderbinen, M., Schaefer, K., Schneeberger, A., Gaab, J., & Garcia Nuñez, D. (2021). Relationship of internalized transnegativity and protective factors with depression, anxiety, non-suicidal self-Injury and suicidal tendency in trans populations: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.636513

Joiner, T. (2021). Myths about suicide. Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1p6hp7n

Khobzi Rotondi, N. (2012). Depression in trans people: A review of the risk factors. International Journal of Transgenderism, 13(3), 104–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2011.663243

Kim, T. S., Cheon, Y. H., Pae, C. U., Kim, J. J., Lee, C. U., Lee, S. J., Paik, I. H., & Lee, C. (2006). Psychological burdens are associated with young male transsexuals in Korea. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 60(4), 417–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1819.2006.01525.x

Kleiman, E. M., Riskind, J. H., & Schaefer, K. E. (2014). Social support and positive events as suicide resiliency factors: Examination of synergistic buffering effects. Archives of Suicide Research, 18(2), 144–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2013.826155

Kota, K. K., Salazar, L. F., Culbreth, R. E., Crosby, R. A., & Jones, J. (2020). Psychosocial mediators of perceived stigma and suicidal ideation among transgender women. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 125. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8177-z

Lelutiu-Weinberger, C., English, D., & Sandanapitchai, P. (2020). The roles of gender affirmation and discrimination in the resilience of transgender individuals in the US. Behavioral Medicine, 46(3–4), 175–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/08964289.2020.1725414

Liu, R. T., & Mustanski, B. (2012). Suicidal ideation and self-harm in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 42(3), 221–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.023

Lobato, M. I., Koff, W. J., Schestatsky, S. S., Chaves, C. P. D. V., Petry, A., Crestana, T., Amaral, J. T., Onófrio, F. D. Q., Salvador, J., Silveira, E., & Henriques, A. A. (2007). Clinical characteristics, psychiatric comorbidities and sociodemographic profile of transsexual patients from an outpatient clinic in Brazil. International Journal of Transgenderism, 10(2), 69–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532730802175148

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

Meyer, I. H. (2014). Minority stress and positive psychology: Convergences and divergences to understanding LGBT health. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 1(4), 348–349. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000070

Modrego Pardo, I., Gómez Balaguer, M., Hurtado Murillo, F., Cuñat Navarro, E., Solá Izquierdo, E., & Morillas Ariño, C. (2021). Self-injurious and suicidal behaviour in a transsexual adolescent and young adult population, treated at a specialised gender identity unit in Spain. Endocrinología, Diabetes y Nutrició (English ed.) 68(5), 338–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.endien.2020.04.009

Moody, C., & Smith, N. G. (2013). Suicide protective factors among trans adults. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42(5), 739–752. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-013-0099-8

Nemoto, T., Bödeker, B., & Iwamoto, M. (2011). Social support, exposure to violence and transphobia, and correlates of depression among male-to-female transgender women with a history of sex work. American Journal of Public Health, 101(10), 1980–1988. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2010.197285

Nock, M. K., Borges, G., Bromet, E. J., Alonso, J., Angermeyer, M., Beautrais, A., Bruffaerts, R., Wai, T. C., De Girolamo, G., Gluzman, S., De Graaf, R., Gureje, O., Haro, J. M., Huang, Y., Karam, E., Kessler, R. C., Lepine, J. P., Levinson, D., Medina-Mora, M. E., & Williams, D. (2008). Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. British Journal of Psychiatry, 192(2), 98–105. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040113

Nuttbrock, L., Hwahng, S., Bockting, W., Rosenblum, A., Mason, M., Macri, M., & Becker, J. (2010). Psychiatric impact of gender-related abuse across the life course of male-to-female transgender persons. Journal of Sex Research, 47(1), 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490903062258

Pellicane, M. J., & Ciesla, J. A. (2022). Associations between minority stress, depression, and suicidal ideation and attempts in transgender and gender diverse (TGD) individuals: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 91, 102–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102113

Peterson, C. M., Matthews, A., Copps-Smith, E., & Conard, L. A. (2017). Suicidality, self-harm, and body dissatisfaction in transgender adolescents and emerging adults with gender dysphoria. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 47(4), 475–482. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12289

Rabasco, A., & Andover, M. (2021). Suicidal ideation among transgender and gender diverse adults: A longitudinal study of risk and protective factors. Journal of Affective Disorders, 278, 136–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.052

Romanelli, M., & Lindsey, M. A. (2020). Patterns of healthcare discrimination among transgender help-seekers. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 58(4), e123–e131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2019.11.002

Saameño, J. A. B., Sánchez, A. D., del Castillo, J. D. D. L., & Claret, P. L. (1996). Validez y fiabilidad del cuestionario de apoyo social funcional Duke-UNC-11. Atención Primaria, 18(4), 153–163.

Shah, H. B. U., Rashid, F., Atif, I., Hydrie, M. Z., Fawad, M. W., Muzaffar, H. Z., Rehman, A., Anjum, S., Mehroz, M., Haider, A., Hassan, A., & Shukar, H. (2018). Challenges faced by marginalized communities such as transgenders in Pakistan. Pan African Medical Journal, 30. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2018.30.96.12818

Snapp, S. D., Watson, R. J., Russell, S. T., Diaz, R. M., & Ryan, C. (2015). Social support networks for LGBT young adults: Low cost strategies for positive adjustment. Family Relations, 64(3), 420–430. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12124

Taylor, P. J., Hutton, P., & Wood, L. (2015). Are people at risk of psychosis also at risk of suicide and self-harm? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 45, 911–926. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291714002074

Terada, S., Matsumoto, Y., Sato, T., Okabe, N., Kishimoto, Y., & Uchitomi, Y. (2011). Suicidal ideation among patients with gender identity disorder. Psychiatry Research, 190(1), 159–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2011.04.024

Testa, R. J., Michaels, M. S., Bliss, W., Rogers, M. L., Balsam, K. F., & Joiner, T. (2017). Suicidal ideation in transgender people: Gender minority stress and interpersonal theory factors. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126(1), 125–136. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000234

Testa, R. J., Sciacca, L. M., Wang, F., Hendricks, M. L., Goldblum, P., Bradford, J., & Bongar, B. (2012). Effects of violence on transgender people. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 43(5), 452–459. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029604

Treharne, G. J., Riggs, D. W., Ellis, S. J., Flett, J. A. M., & Bartholomaeus, C. (2020). Suicidality, self-harm, and their correlates among transgender and cisgender people living in Aotearoa/New Zealand or Australia. International Journal of Transgender Health, 21(4), 440–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2020.1795959

Vaughan, M. D., & Rodriguez, E. M. (2014). LGBT strengths : Incorporating positive psychology into theory, research, training, and practice LGBT psychology: From pathology to strengths. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 1(4), 325–334.

Zinchuk, M., Kustov, G., Beghi, M., Voinova, N., Pashnin, E., & Beghi, E. (2022). Factors associated with non-binary gender identity in psychiatric inpatients with suicidal ideation assigned female at birth : A case-control study. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51(7), 3601–3612. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-022-02424-2

Zucker, K. J. (2019). Adolescents with gender dysphoria: Reflections on some contemporary clinical and research issues. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(7), 1983–1992. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-019-01518-8

Zucker, K. J., Lawrence, A. A., & Kreukels, B. P. C. (2016). Gender dysphoria in adults. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 12(1), 217–247. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093034

Zwickl, S., Angus, L. M., Qi, A. W. F., Ginger, A., Eshin, K., Cook, T., Leemaqz, S. Y., Dowers, E., Zajac, J. D., & Cheung, A. S. (2021). The impact of the first three months of the COVID-19 pandemic on the Australian trans community. International Journal of Transgender Health. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2021.1890659

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all members of the Transsexuality and Gender Identity Unit of the University Regional Hospital of Malaga, and all those with gender dysphoria who participated in this research. The authors wish to thank David W. E. Ramsden for valuable assistance correcting the English version of the manuscript. This project was partially financed by the Health Investigation Fund Carlos III Health Institute. Spanish Ministry of Health, file number 01/0447 entitled: Transsexuality in Andalucía: Endocrine psychiatric morbidity and surgical and evaluation of therapeutic intervention experience by the first unit of reference in Spain (2001e2013). This study was partially supported by grant No. PI06-1339, funded by the Carlos III Health Institute, Spanish Ministry of Health, Social Affairs and Equality, Spain; and by grant No. PI07-0157 funded by the Andalusian Regional Ministry of Health and CTS546 funded by the Andalusian Regional Ministry of Innovation, Andalusia, Spain. Partial funds from EU-FEDER (Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional). YDDO is recipient of a Postdoctoral Research Contract, number RH-0023-2021, from the “Servicio Andaluz de Salud,” Andalusian Regional Ministry of Health. No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or regional research committee (Malaga Province Ethical Committee, without reference number) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

All participants signed an informed consent form before participating in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Guzman-Parra, J., Sánchez-Álvarez, N., Guzik, J. et al. The Impact of Stressful Life Events on Suicidal Ideation in Gender Dysphoria: A Moderator Effect of Perceived Social Support. Arch Sex Behav 52, 2205–2213 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-023-02594-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-023-02594-7