Abstract

The study aimed to investigate factors associated with non-binary gender identity in Russian female psychiatric inpatients with suicidal ideation. This case–control study included 38 female inpatients with non-binary gender identity and a control group—76 cisgender women matched for age (age range 19–35 years, M age, 21.5 years); both groups were psychiatric inpatients with suicidal thoughts. All patients underwent the Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview and completed the brief Reasons for Living Inventory. We also used the WHO Quality of Life Questionnaire (WHOQOL-100) and the Life Style Index (LSI). Non-binary gender identity in inpatients with suicidal ideation was associated with lower educational level, higher unemployment rate, being more socially reticent in preschool, and lifetime sexual experience with both male and female partners. In addition, they were younger at the time of the first suicidal ideation, suicide plan development, and attempt. Non-binary inpatients had lower scores in freedom, physical safety, and security facets of WHOQOL-100 and a higher level of intellectualization on LSI. People with non-binary gender identity face educational, employment, and communication issues. They also have distinct suicidal thoughts and behavioral profiles. These issues and differences mean unique approaches to suicide prevention for a population of inpatients with non-binary gender identity are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

For a long time, sex and gender were believed to be binary. However, recent studies have begun to cast doubts on the unambiguous link between them, proposing that gender should be conceptualized in a non-dichotomous way (Cameron & Stinson, 2019). According to this approach, gender is something we achieve through interactions in our everyday lives rather than an innate characteristic (Darwin, 2017). In the study conducted by Watson et al. (2019), 26 distinct sexual and gender identities were reported, wherein the vast majority of these identities were not exclusively masculine or feminine. The term “transgender” has been introduced for persons whose gender identity does not match the sex assigned at birth. However, it is an umbrella term that covers a broad spectrum of gender identities, including those falling out of the binary system (Watson et al., 2019).

Non-binary gender identity (NBGI) does not fit into traditional binary gender categories, including such identities as pangender, multigender, bigender, gender fluid, demigender, and agender persons (LGBTQIA Resource Centre, 2015). According to recent nonclinical studies, atypical gender identities are not uncommon in the general population. For example, the New Zealand Adolescent Health Survey (Clark et al., 2014) found that 1.2% of high school students identified themselves as transgender/gender non-conforming, whereas an additional 2.5% of participants indicated they were uncertain about their gender. Furthermore, according to meta-regression analysis (Meerwijk & Sevelius, 2017), the number of transgender adults has significantly increased over the past decade, and the US transgender population has reached 390 adults per 100,000—almost 1 million adults nationally.

While atypical gender identity is neither psychopathology nor a somatic disease, these individuals have greater health needs than cisgender people (Scandurra et al., 2019; Warrier et al., 2020). For example, gender diverse people are overrepresented among clinical samples of HIV-positive and people with non-psychotic mental health disorders (NPMD), especially among those with suicidal behavior (Askevis-Leherpeux et al., 2019; Baral et al., 2013; Poteat et al., 2016; Yüksel et al., 2017). It was suggested earlier that non-heterosexual persons experience high rates of minority stress—including bullying, prejudice, and stigma, which are significant risks that could be related to suicide ideation and attempts (Meyer, 2003). This model holds true for NBGI persons (Scandurra et al., 2021).

A recent meta-analysis reported a high mean prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) (28.2% (95% CI 14.8–47.1)), suicidal ideation (28% (95% CI 15–46.3)), and suicide attempts (14.8% (95% CI 7.8–26.3)) in gender non-conforming youths (Surace et al., 2020). In addition, some authors suggest that non-binary identified persons experience higher rates of anxiety and depression and could be at greater risk of adverse mental health outcomes than their binary transgender peers—both in clinical (Thorne et al., 2018) and community samples (Chumakov et al., 2021). However, overall health and well-being are more complicated as people with NBGI might have higher scores on gender congruence, body satisfaction, and psychological functioning than binary trans individuals (Jones et al., 2019a, 2019b).

Today, most studies focus on binary transgender issues, and data on non-binary transgender individuals remain relatively scarce. This approach is problematic because binary transgender experiences do not represent the full complexity of gender identities, and one could not extrapolate existing data on binary transgender persons to NBGI.

In the Russian Federation, transgender people can change their legal gender since 1997 (ILGA World, 2020). Specifically, to access gender confirmation surgery or change legal gender, one needs to be diagnosed with gender dysphoria by a psychiatrist after observation lasting from 1 month to 2 years and then pay for all the transition procedures out of their pocket. Still, there is no quick, transparent, and accessible procedure for legal gender recognition (Transgender Legal Defense Project, 2017), and no legal genders other than male and female; thus, the process is even vaguer for persons with NBGI. Moreover, Russian people with atypical gender identity still find it more difficult to integrate into society than those who live in western European and North American countries. Omnipresent transphobia in the Russian Federation not only causes difficulties in conducting studies and collecting statistical data but also deters transgender and gender non-conforming patients from getting help—either related to transition or somatic and mental health issues (Buyantueva, 2017).

There is limited research on the mental health issues of transgender people in the Russian Federation. The only Russian study on anxiety and depressive symptoms in a transgender sample that included NBGI participants reports both higher prevalence and severity of anxiety and depressive symptoms than in binary transgender persons (Chumakov et al., 2021). There are little data on the gender identities of psychiatric inpatients, and our study aims to contribute to solving this gap. To our knowledge, no published studies have investigated factors associated with suicidal behavior in Russian patients with mental disorders and non-binary gender identity.

As both psychiatric inpatients and people with NBGI are at greater risk of suicide, we aimed to investigate factors associated with NBGI in Russian psychiatric inpatients assigned female at birth with suicidal ideation.

Method

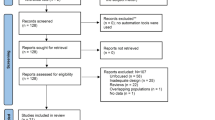

Participants and Procedure

The case–control study included female inpatients with NBGI, aged > 17 years (N = 38, 23 agender and 15 bigender persons) and female cisgender controls (N = 76), matched in age, identified from the cohort of 481 consecutive psychiatric inpatients with suicidal thoughts from the Moscow Research and Clinical Center for Neuropsychiatry. The center only admits patients with non-psychotic mental disorders due to the “open doors” approach. All patients are self-admitted or referred by a general practitioner or other medical specialists due to psychological, psychiatric, or emotional problems unrelated primarily to gender identity. Latter was assessed after admission, and people with NBGI described their gender as a combination of male and female traits or in a way that is not part of the gender binary (Richards et al., 2016). All admitted inpatients (hence having any mental disorder) were invited to participate in the study by the treating psychiatrist and to sign an informed consent before starting. We excluded patients with severe concomitant somatic and neurological disorders (n = 2), substance use disorders (n = 1), and cognitive decline below the level of understanding self-assessment scales and the interviewer's questions (n = 1); we excluded a total of 4 patients. Also, three cisgender people and one NBGI person refused to participate due to unknown reasons. During the first day of hospitalization, experienced psychiatrists examined all the participants and provided the mental disorder diagnosis according to the ICD-10 criteria. Psychiatrists were cisgender, had more than 10 years of practice (including work with LBGTQ+ persons), and considered any NBGI part of normal diversity. All patients were diagnosed with one or more of the following disorders: schizotypal disorder (F21), bipolar disorder (F31), unipolar depression (F32/33), anxiety disorders (F40/F41), obsessive–compulsive disorder (F42), eating disorders (F50), and personality disorders (F60/F61). Participants' demographic, clinical, and behavioral features were collected on the first day of admission through direct interviews and registered in the case record forms (CRF, see Supplementary Appendix 1) designed ad hoc. During the first 3 days of hospitalization, all participants underwent the Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview (SITBI) and completed the brief Reasons for Living Inventory (bRFL), the WHO Quality of Life questionnaire (WHOQOL-100), and the Life Style Index (LSI).

Measures

The Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behavior Interview (SITBI) is a 169-item structured interview to evaluate the presence, frequency, and characteristics of suicide and self-injurious thoughts and behaviors (Nock et al., 2007). A standard backward and forward translation procedure of the original version of SITBI was used to generate the Russian language version of the interview. The final version of the tool is used in Russia both in clinical practice and research settings (Zinchuk et al., 2020), and the study on its psychometric properties is currently in preparation by the mentioned authors.

Brief Reasons for Living inventory (bRFL) is a 12-item self-report instrument intended to evaluate adaptive beliefs and expectations for living (Ivanoff et al., 1994). The Russian language version of the bRFL was extracted from the Russian version of the 48-item Reasons for Living inventory. This version was forward-back translated by Chistopol'skaya et al. (2017) concerning relevant guidelines for the translation of psychometric instruments and validated on the clinical sample of psychiatric inpatients (Pashnin et al., 2022). The brief version of the tool replicated the original English and German versions of the bRFL (Kustov et al., 2021), with higher scores in bRFL reflecting better coping strategies helping to reduce suicide risk.

The World Health Organization Quality of Life Group (WHOQOL-100) questionnaire is a 100-item self-administered inventory to assess different aspects of the quality of life (The WHOQOL GROUP, 1998). The questionnaire evaluates 24 facets grouped into six domains: Physical, Psychological, Level of Independence, Social Relationships, Environment, and Spirituality. It also evaluates the overall quality of life and perception of life. The Russian version of the WHOQOL-100 proved to be a reliable and valid tool for patients with mental disorders (Burkovskiy, 1998). Higher scores in WHOQoL-100 reflected a better quality of life.

The Life Style Index (LSI) is a 97-item self-report questionnaire to assess eight ego defense mechanisms: compensation, denial, displacement, intellectualization, projection, reaction formation, regression, and repression (Plutchik & Conte, 1989). The Russian version of LSI has gone through all the necessary steps of psychometric evaluation and established itself as a reliable tool for evaluating ego defense mechanisms (Vasserman et al., 2005). Higher rates on LSI subscales reflect a degree of the defense mechanisms' tension.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical values are presented as numbers and percentages, while continuous variables as mean and standard deviation (SD). We used the Mann–Whitney U-test to compare quantitative variables and Pearson's chi-square (χ2) for categorical variables.

The study was approved by the local ethics committee of the Moscow Research and Clinical Center for Neuropsychiatry. Trained psychiatrists obtained written informed consent from all the patients who participated in the study.

Results

Demographics

The mean age of the whole sample was 21.5 (3.5) years, with an age range of 19–35 years. Inpatients with NBGI had a lower educational level (p = 0.005) and worse occupational status (p = 0.018). There were no differences between the two groups on employment and marital status (Table 1). No patients had any history of gender-affirming medical interventions.

According to personal history analysis, inpatients with NBGI were more socially reticent in preschool (χ2 = 13.52, p < 0.001) and were bullied at school more often (χ2 = 7.20, p = 0.007) than their cisgender peers. In addition, NBGI inpatients had more frequent sexual experiences with both male and female assigned at birth partners (χ2 = 10.16, p = 0.001). Family history of mental condition and suicidality, traumatic experience, and past or current psychiatric diagnosis did not differ statistically between the groups (Table 1).

Suicidal Thoughts and Behavior

In the whole sample, a significant number of inpatients had a lifetime history of suicide plan development (n = 73; 64%), suicide attempt (n = 55; 48.2%), and NSSI (n = 91; 79.8%), but no difference between the groups was found. Meanwhile, NBGI inpatients were younger than controls at the time of the first suicidal ideation (p = 0.013), suicide plan development (p = 0.005), and suicide attempt (p = 0.003) (Table 2). In line with an overall similar suicidality profile, we found no differences between cases and controls on the reasons for living (based on the bRFL, all: p > 0.05) (Table 3).

Quality of Life and Lifestyle

NBGI inpatients had substantially lower scores in freedom, physical safety, and security facets of WHOQOL-100 (p = 0.05). Inpatients with NBGI tended to present lower scores of positive fillings facet (p = 0.057) and environment facet (p = 0.051). There were no significant differences between the two groups regarding other categories of WHOQOL-100 (Table 4).

Regression and projection were the two most common defense mechanisms in both groups. A higher level of intellectualization z (p = 0.01) in NBGI inpatients was the only difference between the two groups on LSI (Table 5).

Discussion

In our study, we did not find significant differences between NBGI persons and cisgenders regarding most of the characteristics of self-injurious thoughts and behaviors except for a younger age of onset of suicidal thoughts, the development of a suicide plan, and the first suicide attempt among non-binary persons.

The risk of suicidal ideation and behavior in people with atypical gender identities is higher than in the general and non-heterosexual populations (Marshall et al., 2015; Surace et al., 2020). Previous studies reported a higher risk of suicidal thoughts and attempts in people with NBGI compared to cisgender controls (Aparicio-García et al., 2018; Horwitz et al., 2020), but the data on the difference between NBGI and binary transgender people are contradictory, with reports on a higher, (Aparicio-García et al., 2018) a lower (Warren et al., 2016), and the same (Horwitz et al., 2020) prevalence.

A recent study from the Russian Federation reported a high prevalence of lifetime NSSI in psychiatric inpatients and suicidal ideation (Zinchuk et al., 2020). According to a recent meta-analysis (Liu et al., 2019), the life-time prevalence of the NSSI in transgender populations in transgender populations is 46.65%, which exceeds that of both people with atypical sexual orientation (29.68%) and cisgender persons (14.57%). Studies on the prevalence of NSSI among people with NBGI are sporadic but show both high and equal prevalence of NSSI (60.7%-77%) compared to binary transgender people (Clark et al., 2018; Rimes et al., 2017; Veale et al., 2017). In our clinical sample, the effect (if one exists) of gender identity on suicidal plans prevalence could be masked by overall psychopathology—personality disorders and depression could have a more substantial impact on self-injurious thoughts and behaviors.

Inpatients with NBGI were younger at the onset of suicidal thoughts, developing a suicide plan, and attempting suicide for the first time. One hypothesis is that the earlier onset of suicidality in people with NBGI is probably related to the higher prevalence of bullying in childhood and adolescence. This is consistent with previous data on binary transgender people (Clark et al., 2014; Hatchel & Marx, 2018; Kosciw et al., 2012) and on people with NBGI, for which an increased prevalence of polyvictimization was found (Sterzing et al., 2017). The 2015 National School Climate Survey in the US showed that almost 50% of students with NBGI had faced verbal harassment related to their gender expression, and 15% of them have been physically abused at least once for the same reason. School bullying in post-Soviet countries remains a pressing challenge. According to the WHO report, up to 27% of Russian children face bullying at school regularly (WHO, 2013). School bullying remains a pressing challenge worldwide, and 97% of Russian transgender students face bullying from their peers and 53%—from their teachers (Ushkova & Kireev, 2017).

School bullying based on sexual orientation and gender identity perceptions may have negative long-term consequences affecting social, psychological, and physical well-being (A. Jones et al., 2017). Several studies have shown that school bullying leads to the fear of going to school, difficulties in concentration during classes, and lower academic performance (Espelage et al., 2013; Fry et al., 2018; UNESCO, 2017). Low educational levels in NBGI inpatients may also result from a bullying experience. The 2017 National School Climate Survey (Kosciw et al., 2018) results indicate that almost 70% of students with NBGI skip classes due to the fear of discrimination regarding their sexual orientation or gender identity, resulting in lower academic performance. Our data on lower occupational status among NBGI inpatients are consistent with previous reports on the association between high victimization and a lower probability of post-secondary education (Kosciw et al., 2015). Hence, the problem that is prominent even in cisgender women is even worse in NBGI females. In addition, in many countries, including Russia, female biological sex remains a risk factor for workplace victimization (Difazio et al., 2018).

Participants with NBGI were more socially reticent in the preschool period than cisgender controls. This finding aligns with the reportedly high risk of being alienated and bullied from early childhood by peers for children who do not gain social communication skills (Jenkins et al., 2017).

Non-heterosexual orientation is another common reason for discrimination against NBGI people (Kosciw et al., 2015). In our study, 50% of NBGI inpatients have had sexual partners of both sexes. Most inpatients with NBGI reported that they preferred to have a relationship with another non-binary person. This supports the idea that a classic approach for determining one's sexual orientation is unsuitable for NBGI persons. For example, the most common tool used in Russia to evaluate sexual orientation is Klein Sexual Orientation Grid, which is binary oriented.

In our sample, the quality of life did not differ substantially between the groups, except for the environment domain (borderline statistical significance). However, at the level of the facets, a lower score in the «freedom, physical safety and security» facet could be a result of bullying and negative attitude toward the LGBT + (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender and related communities) community and stands for the impairment in the environment domain, in line with other findings from the Belgium study (Motmans et al., 2012). In the same study, transgender men (compared to women) had poorer quality of life related to mental health compared to men from the general population. However, the findings in other cultural contexts could differ substantially. For example, Valashany and Janghorbani (2018) reported a significantly worse quality of life for transgender people living in Iran (Valashany & Janghorbani, 2018). Further transcultural studies on a larger population are required to test this hypothesis.

Participants from both groups relied mainly on immature defenses (especially projection and regression) to deal with emotional stress. Several studies on people with mental disorders have reported an association of immature defense mechanisms with many unfavorable outcomes, including suicidal behavior (Brody & Carson, 2011; Corruble et al., 2004). Unfortunately, the data on the defense mechanisms of people with atypical gender identity are scarce (Lobato et al., 2009) and come predominantly from studies done on candidates for gender confirmation surgery (Prunas et al., 2014), which prevents us from drawing any significant conclusions.

Studies on reasons for living in patients with atypical gender are scarce. Moody and Smith (2013) stated that there is a «significant relationship between some factors typically found to protect cis individuals from suicidal behavior and trans individuals' suicidal behavior», but 86.5% of the participants in that study identified themselves as FTM (female to male) and MTF (male to female). In previous studies, the 48-item version of RFL was used. We used the brief version of RFL in our study because its structurally similar to the original version and has fewer questions—12. According to our knowledge, the short version of RFL was never used before in studies in non-heterosexual and transgender populations. We found no significant differences in reasons for living between the groups.

Creating a supportive school climate for sexual and gender minority youth has reduced suicide risk (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2014). The association of NBGI and the level of bullying in our sample support this approach. However, most studies represent nonclinical samples. Our data on specific defense mechanisms and reasons for living could tailor and guide new approaches to reduce suicidal risk or primarily prevent suicide (for example, in the framework of cognitive-behavioral methods) and increase the quality of life specifically for psychiatric inpatients with NBGI. Moreover, interventions directed at mental health professionals and the community should be promoted to fight against the stigmatization and social isolation of these persons.

Strengths and Limitations

The study contributes to a better understanding of the distinguishing features of NBGI people with mental disorders and suicidal ideation. Our study is the first in Russia to address the problem of suicidal behavior in psychiatric inpatients with NBGI. However, our findings align with similar surveys in other countries. Since we used several tools validated in many countries and the full version of our questionnaire is available to readers (see Appendix), our research methodology can be easily reproduced. Such studies will allow the comparison of data from different populations and provide an understanding of the specific cultural features of patients with NBGI.

There are, however, several limitations. The first is the retrospective design. We may not acknowledge potential confounding factors to both psychopathology and suicidality, and the studied group is non-homogenous—for example, we could not extract enough data on male persons with NBGI. We also might have lost patients who died by having committed suicide or for some other reasons.

The baseline characteristics of the cohort represent the second limitation. Both cases and controls were admitted to our center as having psychiatric symptoms, so they do not represent the general population of people with suicidal thoughts or NBGI. Our findings should be interpreted with this limitation in mind. Perhaps the differences might be even greater with controls from the general populations, and some non-significant comparisons might have become significant. Our cohort's absence of psychotic mental disorders makes it impossible to draw a conclusion regarding all women with NBGI, mental disorders, and suicidal ideation.

The third limitation is the sample size that is insufficient to make intra-group comparisons among different NBGI subtypes, among inpatients with suicidal thoughts only, and among those with suicide attempts in the past. Moreover, the sample size could only be suitable for analysis regarding the female inpatients: male inpatients represented less than one-fourth of the original cohort and a cohort of people with NBGI, which could not allow us to analyze all NBGI inpatients altogether.

Conclusions

NBGI inpatients with NPMD and suicidal ideation have several distinct features. Compared to cisgender participants, those with NBGI were less educated, had lower occupational status, faced difficulties in communication with peers in the preschool period, and were bullied at school more often. Sexual experience with both biological sexes is more prevalent in inpatients with NBGI. Finally, more frequent use of intellectualization distinguished the defense mechanism profile of NBGI from that of cisgender inpatients.

Availability of Data and Material

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Aparicio-García, M., Díaz-Ramiro, E., Rubio-Valdehita, S., López-Núñez, M., & García-Nieto, I. (2018). Health and well-being of cisgender, transgender and non-binary young people. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(10), 2133. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15102133

Askevis-Leherpeux, F., de la Chenelière, M., Baleige, A., Chouchane, S., Martin, M., Robles-García, R., et al. (2019). Why and how to support depsychiatrisation of adult transidentity in ICD-11: A French study. European Psychiatry, 59, 8–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2019.03.005

Baral, S., Poteat, T., Strömdahl, S., Wirtz, A., Guadamuz, T., & Beyrer, C. (2013). Worldwide burden of HIV in transgender women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 13(3), 214–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1473-3099(12)70315-8

Brody, S., & Carson, C. (2011). Brief report: Self-harm is associated with immature defense mechanisms but not substance use in a nonclinical Scottish adolescent sample. Journal of Adolescence, 35(3), 765–767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.09.001

Burkovskiy, G. (1998). Application of WHO Quality of Life Inventory in psychiatric practice: Guide for doctors and psychologists. Bekhterev Psychoneurological Research Institute.

Buyantueva, R. (2017). LGBT rights activism and homophobia in Russia. Journal of Homosexuality, 65(4), 456–483. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2017.1320167

Cameron, J., & Stinson, D. (2019). Gender (mis)measurement: Guidelines for respecting gender diversity in psychological research. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 13. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12506

Chiam, Z., Duffy, S., González, M., Goodwin, L., Timothy, N., & Patel, M. (2020). Trans Legal Mapping Report 2019: Recognition Before the Law. Geneva. Retrieved 30 August 2022, from https://worldconference.ilga.org/trans-legal-mapping-report-2019

Chistopolskaya, K., Zhuravleva, T., Enikolopov, S., & Nikolaev, E. (2017). Adaptation of diagnostic instruments for suicidal aspects of personality. Psychology. Journal of the Higher School of Economics, 14(1), 61–87.

Chumakov, E., Ashenbrenner, Y., Petrova, N., Zastrozhin, M., Azarova, L., & Limankin, O. (2021). Anxiety and depression among transgender people: Findings from a cross-sectional online survey in Russia. LGBT Health, 8(6), 412–419. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2020.0464

Clark, B., Veale, J., Townsend, M., Frohard-Dourlent, H., & Saewyc, E. (2018). Non-binary youth: Access to gender-affirming primary health care. International Journal of Transgenderism, 19(2), 158–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2017.1394954

Clark, T., Lucassen, M., Bullen, P., Denny, S., Fleming, T., Robinson, E., & Rossen, F. (2014). The health and well-being of transgender high school students: Results from the New Zealand Adolescent Health Survey (Youth’12). Journal of Adolescent Health, 55(1), 93–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.11.008

Corruble, E., Bronnec, M., Falissard, B., & Hardy, P. (2004). Defense styles in depressed suicide attempters. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 58(3), 285–288. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1819.2004.01233.x

Darwin, H. (2017). Doing gender beyond the binary: A virtual ethnography. Symbolic Interaction, 40(3), 317–334. https://doi.org/10.1002/symb.316

Difazio, R., Vessey, J., Buchko, O., Chetverikov, D., Sarkisova, V., & Serebrennikova, N. (2018). The incidence and outcomes of nurse bullying in the Russian Federation. International Nursing Review, 66(1), 94–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12479

Espelage, D., Hong, J., Rao, M., & Low, S. (2013). Associations between peer victimization and academic performance. Theory into Practice, 52(4), 233–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2013.829724

Fry, D., Fang, X., Elliott, S., Casey, T., Zheng, X., Li, J., et al. (2018). The relationships between violence in childhood and educational outcomes: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect, 75, 6–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.06.021

Hatchel, T., & Marx, R. (2018). Understanding intersectionality and resiliency among transgender adolescents: Exploring pathways among peer victimization, school belonging, and drug use. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(6), 1289. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15061289

Hatzenbuehler, M., Birkett, M., Van Wagenen, A., & Meyer, I. (2014). Protective school climates and reduced risk for suicide ideation in sexual minority youths. American Journal of Public Health, 104(2), 279–286. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2013.301508

Horwitz, A., Berona, J., Busby, D., Eisenberg, D., Zheng, K., Pistorello, J., et al. (2020). Variation in suicide risk among subgroups of sexual and gender minority college students. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 50(5), 1041–1053. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12637

Ivanoff, A., Jang, S., Smyth, N., & Linehan, M. (1994). Fewer reasons for staying alive when you are thinking of killing yourself: The brief Reasons for Living Inventory. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 16(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02229062

Jenkins, L., Mulvey, N., & Floress, M. (2017). Social and language skills as predictors of bullying roles in early childhood: A narrative summary of the literature. Education and Treatment of Children, 40(3), 401–417. https://doi.org/10.1353/etc.2017.0017

Jones, A., Robinson, E., Oginni, O., Rahman, Q., & Rimes, K. (2017). Anxiety disorders, gender nonconformity, bullying and self-esteem in sexual minority adolescents: Prospective birth cohort study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(11), 1201–1209. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12757

Jones, B., Pierre Bouman, W., Haycraft, E., & Arcelus, J. (2019a). Gender congruence and body satisfaction in nonbinary transgender people: A case control study. International Journal of Transgenderism, 20(2–3), 263–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2018.1538840

Jones, B., Pierre Bouman, W., Haycraft, E., & Arcelus, J. (2019b). Mental health and quality of life in non-binary transgender adults: A case control study. International Journal of Transgenderism, 20(2–3), 251–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2019.1630346

Kosciw, J., Bartikiowicz, M., & Greytak, E. (2012). Promising strategies for prevention of the bullying of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth. Psycextra Dataset. https://doi.org/10.1037/e534992013-004

Kosciw, J. G., Greytak, E. A., Giga, N. M., Villenas, C., & Danischewski, D. J. (2016). The 2015 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer youth in our nation’s schools. GLSEN.

Kosciw, J. G., Greytak, E. A., Zongrone, A. D., Clark, C. M., & Truong, N. L. (2018). The 2017 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer youth in our nation’s schools. GLSEN.

Kustov, G. V., Zinchuk, M. S., Gersamija, A. G., Voinova, N. I., Yakovlev, A. A., Avedisova, A. S., & Guekht, A. B. (2021). Psychometric properties of the Russian version of the brief “Reasons for Living Inventory”. S.S. Korsakov Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry, 121(10), 87–94. https://doi.org/10.17116/jnevro202112110187

LGBTQIA Resource Centre. (2020). LGBTQIA resource centre glossary. Retrieved 30 August 2022, from http://lgbtqia.ucdavis.edu/educated/glossary.html.

Liu, R., Sheehan, A., Walsh, R., Sanzari, C., Cheek, S., & Hernandez, E. (2019). Prevalence and correlates of non-suicidal self-injury among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 74, 101783. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2019.101783

Lobato, M., Koff, W., Crestana, T., Chaves, C., Salvador, J., Petry, A., et al. (2009). Using the defensive style questionnaire to evaluate the impact of sex reassignment surgery on defensive mechanisms in transsexual patients. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 31(4), 303–306. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1516-44462009005000007

Marshall, E., Claes, L., Bouman, W., Witcomb, G., & Arcelus, J. (2015). Non-suicidal self-injury and suicidality in trans people: A systematic review of the literature. International Review of Psychiatry, 28(1), 58–69. https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2015.1073143

Meerwijk, E., & Sevelius, J. (2017). Transgender population size in the United States: A meta-regression of population-based probability samples. American Journal of Public Health, 107(2), e1–e8. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2016.303578

Meyer, I. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

Moody, C., & Smith, N. (2013). Suicide protective factors among trans adults. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42(5), 739–752. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-013-0099-8

Motmans, J., Meier, P., Ponnet, K., & T’Sjoen, G. (2012). Female and male transgender quality of life: Socioeconomic and medical differences. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 9(3), 743–750. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02569.x

Nock, M., Holmberg, E., Photos, V., & Michel, B. (2007). Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview: Development, reliability, and validity in an adolescent sample. Psychological Assessment, 19(3), 309–317. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.19.3.309

Pashnin, E., Zinchuk, M., Gersamia, A., Voinova, N., Yakovlev, A., Avedisova, A., & Guekht, A. (2022). Verification of Reasons for Living Inventory in Russian clinical sample. Psikhologicheskii Zhurnal, 43(1), 109–121.

Plutchik, R., & Conte, H. R. (1989). Measuring emotions and their derivatives: Personality traits, ego defenses, and coping styles. In S. Wetzler & M. M. Katz (Eds.), Contemporary approaches to psychological assessment (pp. 239–269). Brunner/Mazel.

Poteat, T., Scheim, A., Xavier, J., Reisner, S., & Baral, S. (2016). Global epidemiology of HIV infection and related syndemics affecting transgender people. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 72(3), S210–S219. https://doi.org/10.1097/qai.0000000000001087

Prunas, A., Vitelli, R., Agnello, F., Curti, E., Fazzari, P., Giannini, F., et al. (2014). Defensive functioning in MtF and FtM transsexuals. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 55(4), 966–971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.12.009

Richards, C., Bouman, W., Seal, L., Barker, M., Nieder, T., & T’Sjoen, G. (2016). Non-binary or genderqueer genders. International Review of Psychiatry, 28(1), 95–102. https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2015.1106446

Rimes, K., Goodship, N., Ussher, G., Baker, D., & West, E. (2017). Non-binary and binary transgender youth: Comparison of mental health, self-harm, suicidality, substance use and victimization experiences. International Journal of Transgenderism, 20(2–3), 230–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2017.1370627

Scandurra, C., Carbone, A., Baiocco, R., Mezzalira, S., Maldonato, N., & Bochicchio, V. (2021). Gender identity milestones, minority stress and mental health in three generational cohorts of Italian binary and nonbinary transgender people. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(17), 9057. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179057

Scandurra, C., Mezza, F., Maldonato, N., Bottone, M., Bochicchio, V., Valerio, P., & Vitelli, R. (2019). Health of non-binary and genderqueer people: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01453

Sterzing, P., Ratliff, G., Gartner, R., McGeough, B., & Johnson, K. (2017). Social ecological correlates of polyvictimization among a national sample of transgender, genderqueer, and cisgender sexual minority adolescents. Child Abuse & Neglect, 67, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.02.017

Surace, T., Fusar-Poli, L., Vozza, L., Cavone, V., Arcidiacono, C., Mammano, R., et al. (2020). Lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicidal behaviors in gender non-conforming youths: A meta-analysis. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 30(8), 1147–1161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01508-5

The WHOQOL Group. (1998). The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL): Development and general psychometric properties. Social Science & Medicine, 46(12), 1569–1585. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00009-4

Thorne, N., Witcomb, G., Nieder, T., Nixon, E., Yip, A., & Arcelus, J. (2018). A comparison of mental health symptomatology and levels of social support in young treatment seeking transgender individuals who identify as binary and non-binary. International Journal of Transgenderism, 20(2–3), 241–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2018.1452660

Transgender Legal Defense Project. (2017). Retrieved 30 August 2022, from https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CESCR/Shared%20Documents/RUS/INT_CESCR_CSS_RUS_28825_E.pdf.

UNESCO. (2017). School violence and bullying: Global status report. Presented at the International Symposium on School Violence and Bullying: From Evidence to Action. Retrieved 30 August 2022, from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000246970.

Ushkova, I. V., & Kireev, E. Y. (2017). Transgender in the modern Russian society. The Monitoring of Public Opinion Economic & Social Changes, 2(138), 82–96.

Valashany, B. T., & Janghorbani, M. (2018). Quality of life of men and women with gender identity disorder. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-018-0995-7

Vasserman, L., Eryshev, O., & Klubova, E. (2005). Psychological diagnosis of Life Style Index. Bekhterev Psychoneurological Research Institute.

Veale, J., Watson, R., Peter, T., & Saewyc, E. (2017). Mental health disparities among Canadian transgender youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 60(1), 44–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.09.014

Warren, J., Smalley, K., & Barefoot, K. (2016). Psychological well-being among transgender and genderqueer individuals. International Journal of Transgenderism, 17(3–4), 114–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2016.1216344

Warrier, V., Greenberg, D., Weir, E., Buckingham, C., Smith, P., Lai, M., et al. (2020). Elevated rates of autism, other neurodevelopmental and psychiatric diagnoses, and autistic traits in transgender and gender-diverse individuals. Nature Communications, 11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17794-1

Watson, R., Wheldon, C., & Puhl, R. (2019). Evidence of diverse identities in a large national sample of sexual and gender minority adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 30(S2), 431–442. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12488

WHO. (2013). Bullying among adolescents in the Russian Federation. Fact sheet based on the results of Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) Survey 2013/2014. Retrieved 30 August 2022, from http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/325511/HSBC-Fact-Sheet-Alcohol-use-among-adolescents-in-the-Russian-Federation.pdf.

Yuksel, S., Aslantas Ertekin, B., Ozturk, M., Bikmaz, P., & Oglagu, Z. (2017). A clinically neglected topic: Risk of suicide in transgender individuals. Noro Psikiyatri Arsivi, 54(1), 28–32. https://doi.org/10.5152/npa.2016.10075

Zinchuk, M., Beghi, M., Beghi, E., Bianchi, E., Avedisova, A., Yakovlev, A., & Guekht, A. (2020). Non-suicidal self-injury in Russian patients with suicidal ideation. Archives of Suicide Research, 26(2), 776–800. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2020.1833801

Acknowledgements

The authors are indebted to the following persons who helped them in doing technical work: Drs. Popova Sofya (manuscript preparation), Raguzin Anton (data acquisition), Sviatskaia Ekaterina (translation, data acquisition).

Funding

This study was performed as a part of the research program of the Moscow Research and Clinical Center for Neuropsychiatry. No grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors were obtained.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MZ took part in conceptualization, manuscript writing, and data acquisition. GK took part in data acquisition, manuscript writing, and statistical analysis. MB involved in literature review, conceptualization, manuscript writing. NV took part in data acquisition, manuscript writing, and review. EP involved in data acquisition, manuscript writing, and review. EB involved in methodology, manuscript writing, and review. AA took part in conceptualization and manuscript review. AG took part in conceptualization and manuscript review. All authors reviewed and approved the article prior to submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

Ettore Beghi reports grants from the Italian Ministry of Health, grants from SOBI Pharma Company, personal compensation from Arvelle Therapeutics for advisory board meeting, and compensation for meeting attendance from UCB-Pharma. None of these disclosures are in conflict with his contribution.

The remaining authors have no competing interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethical Approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Local Ethics Committee of Moscow research and Clinical Center for Neuropsychiatry.

Consent to Participate

Trained psychiatrists obtained written informed consent from all the patients who participated in the study.

Consent for Publication

All authors reviewed the latest version of the manuscript and approved it for the publication.

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zinchuk, M., Kustov, G., Beghi, M. et al. Factors Associated with Non-Binary Gender Identity in Psychiatric Inpatients with Suicidal Ideation Assigned Female at Birth: A Case-Control Study. Arch Sex Behav 51, 3601–3612 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-022-02424-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-022-02424-2