Abstract

In daily life, women often experience various forms of sexual objectification such as being stared at in public settings and receiving unsolicited sexual remarks on social media. These incidents could have damaging effects on women’s physical and mental health, necessitating ways to respond to the experience. Researchers have provided burgeoning evidence demonstrating the effects of sexual objectification on various psychological, emotional, and cognitive outcomes. However, relatively few researchers have tested how sexually objectified people behaviorally react to the objectification experience. To address this knowledge gap, we aimed to test whether sexual objectification increases dishonesty among women and reveal one potential underlying psychological mechanism. We predicted that sexual objectification increases dishonesty serially through higher levels of relative deprivation and lower levels of self-regulation. We conducted two experiments (valid N = 150 and 279, respectively) to test the predictions and found that participants who experienced sexual objectification reported greater dishonest tendencies than those who did not (Experiments 1 and 2). Moreover, relative deprivation and self-regulation serially mediated the effect of sexual objectification on dishonesty (Experiment 2). In the current experiments, we highlight the essential role of relative deprivation and self-regulation in explaining how sexual objectification increases dishonesty and various related forms of antisocial behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Despite efforts to combat gender inequality in the past century, many societies and cultures still find breaking such rigid norms difficult. Even in relatively liberal countries, females often report experiencing harassment and maltreatment in different settings (Holland et al., 2017; Kozee et al., 2007). One such example is women’s experience of sexual objectification whereby they are treated as tools to fulfill men’s sexual desires (Nussbaum, 1999). These incidents, ranging from receiving harassing appearance-related comments to being solely recognized based on sexual functions, are highly prevalent in women’s social experiences (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997; Holland et al., 2017). Therefore, it is crucial to examine their impacts.

Previous research has identified a myriad of negative correlates and outcomes of sexual objectification victimization, including mental health issues (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997), interpersonal problems (Teng & Poon, 2020), disordered eating (Holmes & Johnson, 2017), and insomnia (Jiang et al., 2022). In addition, being sexually objectified threatens women’s fundamental need satisfaction, causing them to feel lonelier and decreasing their self-regulation ability (Dvir et al., 2021). However, relatively little research has tested how women may behaviorally respond to their objectification experiences. In the present research, we argued that encountering sexual objectification increases women’s relative deprivation and lowers their self-regulation, thereby increasing dishonesty.

Objectification and Relative Deprivation

Relative deprivation refers to people’s feelings of resentment and anger when they perceive themselves as being deprived of a desired or deserved outcome compared to similar others (Callan et al., 2011; Smith et al., 2012). These similar others may be similar in numerous different ways, including gender, workplace roles, or cultural background. Previous research has often examined stable intrapersonal factors that predispose individuals to feel relatively deprived, such as subjective socioeconomic status (Greitemeyer & Sagioglou, 2016), neighborhood disadvantage (Dennison & Swisher, 2019), and low-income perception (Burraston et al., 2019). However, relative deprivation has also been conceptualized as being based on situational appraisals (Smith & Pettigrew, 2014); therefore, its antecedents at the state level should also be considered. Past studies have demonstrated some situational factors that influence state-level relative deprivation, including personal identity salience cues (Kawakami & Dion, 1993) and materialistic cues (Zhang & Zhang, 2016). Further, an experimental paradigm involving participants imagining that they receive help was found to increase their state relative deprivation when the help was from someone of a higher status and when the type of help reinforced the status discrepancy rather than encourage self-reliance (Zhang et al., 2020). Despite these findings, insufficient research has investigated whether interpersonal maltreatment could be a situational risk factor for state relative deprivation. In the present research, we aimed to fill this knowledge gap by examining whether sexual objectification, a highly prevalent form of interpersonal maltreatment, may increase state relative deprivation.

Sexual objectification occurs in everyday social interactions when women are primarily evaluated based on their appearances, which are separated from their personalities, to satisfy others’ sexual desires (Holland et al., 2017; Nussbaum, 1999; Szymanski et al., 2011). The process of sexual objectification often dehumanizes women, labeling them as inferior (LeMoncheck, 1985). Objectification theory (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997) posits that women may perceive themselves based on the observers’ perspective and are motivated to align with these social expectations, leading to feelings of shame and anxiety. Being objectified also leads to feelings of social rejection (Dvir et al., 2021), decreases sexual satisfaction (Clapp & Syed, 2021), and increases psychopathological symptoms (Holmes & Johnson, 2017; Jiang et al., 2022).

Moreover, according to self-determination theory, individuals have intrinsic basic psychological needs for autonomy and competence in order to actualize their potential (Ryan & Deci, 2000); however, objectification obstructs the satisfaction of these needs (e.g., Poon et al., 2020a; Vaes et al., 2011). Objectification denies the target of autonomy because their wishes are not respected and are overshadowed by the fulfillment of the perpetrator’s desires (Nussbaum, 1999). In addition, experiencing sexual objectification leads to perceptions of the target as less competent among themselves (Loughnan et al., 2017) and others (Heflick & Goldenberg, 2014). Therefore, by thwarting the needs for autonomy and competence, objectification also obstructs targets’ pursuits of self-actualization (Smith et al., 2012), such as their growth, development, well-being, and potential (Nussbaum, 1999).

Given these extensive outcomes, we argued that experiencing sexual objectification and its consequences may elicit feelings of being relatively deprived compared to similar others who are not perceived to experience objectification. For example, in the context of workplace or school sexual objectification, an objectified woman may feel deprived in comparison to colleagues or classmates who are not perceived to be objectified. The target of objectification in this context may view that nonobjectified colleagues or classmates are evaluated based on the quality of their work rather than their appearances, causing anger or resentment over being denied the treatment given to these similar others. It is noteworthy that the similar others against whom objectified women compare themselves may, in fact, experience objectification as well; however, relative deprivation is based only on the perception of deprivation compared to similar others (Smith & Pettigrew, 2014). Thus, an objectified target may feel relatively deprived even when compared to other objectified individuals so long as the objectified target does not recognize the similar others as being objectified.

To our knowledge, no prior empirical studies have directly examined the effect of sexual objectification on women’s feelings of relative deprivation, but indirect evidence lends support to such a prediction. For example, sexually objectified women have been shown to perceive themselves as having reduced social power (Shepherd, 2019), which has been associated with feelings of relative deprivation (Kim et al., 2017). Moreover, the satisfaction of basic psychological needs has been demonstrated to be negatively associated with experiences of relative deprivation (Xie et al., 2018). Because sexual objectification thwarts the satisfaction of basic needs (Dvir et al., 2021), we expect that it should also be related to relative deprivation. Further, women who experienced workplace gender discrimination, such as being denied promotions and training opportunities on the basis of gender, were shown to feel more relative deprivation when comparing themselves to men across two studies (Triana et al., 2019). Given that sexual objectification of women may be considered one kind of gender discrimination (Brinkman & Rickard, 2009; Sáez et al., 2019), despite not being included in the above research, this study indirectly supports our prediction that objectification predicts relative deprivation. Altogether, these findings give credence to the role of sexual objectification in provoking women’s feelings of relative deprivation. Thus, in the present research, we sought to experimentally examine whether female victims of sexual objectification would perceive higher relative deprivation than their nonobjectified counterparts.

Sexual Objectification, Relative Deprivation, and Self-Regulation

The pleasure principle posits that people are constantly motivated to obtain immediate pleasures and benefits (Laplanche & Pontalis, 2018). However, such desires may violate personal and societal norms or standards over time. Therefore, to facilitate social harmony and avoid being punished, one must suppress desires for these short-term benefits for more long-term gains (Ciarocco et al., 2012). To achieve this, self-regulation, which refers to intentionally altering one’s self-oriented desires to meet personal and societal standards (Baumeister & Vohs, 2016), is required as an essential cognitive process.

Because self-regulation is effortful, much motivation and attention are needed when executing it (Baumeister & Vohs, 2016; Gillebaart, 2018). Instead of a one–off achievement, self-regulation often requires frequent small acts of inhibiting moods, urges, and thoughts, a concept that is supported by the strength model of self-control (Hagger & Chatzisarantis, 2013). Extensive research has shown that self-regulation is correlated with various long-term positive outcomes, including better academic performance (Troll et al., 2021), lower aggression (Agbaria, 2021), a higher tendency to forgive (Liu & Li, 2020), and better physical and psychological health (Miller et al., 2011). Therefore, researchers have asserted that self-regulation efforts are required to control impulses and attain long-term benefits.

The relative deprivation objectified women experience when they are denied full human attributions and opportunities may result in reduced self-regulation in two ways. First, objectified women may devote more available resources to processing and ruminating on their perceived relative deprivation because, as past research has suggested, relative deprivation is related to mental preoccupation with justice (Callan et al., 2008). This leaves less of one’s limited cognitive resources for self-regulation. Second, their feelings of deprivation may cause them to feel that they are not reaping the benefits of self-regulation, leading them to perceive these efforts as pointless and, instead, selectively reduce self-regulation (Bandura, 1999). As a result, objectified women may morally disengage and behave in ways that satisfy their current impulses, even at the expense of future costs (Bandura, 1999; Stephens, 2018).

Our prediction that relative deprivation may reduce self-regulation has received some indirect support. In one experimental study (Sim et al., 2018), relatively deprived participants faced difficulty resisting the temptation to consume delicious high-calorie food, showing weaker self-regulation and disregard for their long-term health. Importantly, previous studies have found that experiencing sexual harassment may increase binge eating (e.g., Buchanan et al., 2013). Low self-regulation may also manifest as other maladaptive behaviors following sexual objectification and relative deprivation. A gambling experiment revealed similar results, with relative deprivation increasing people’s preference for immediate gratification that earned smaller rewards (Callan et al., 2011). More generally, both correlational and experimental studies have revealed that relative deprivation is positively associated with variables that result from self-regulation failures, such as impulsivity (Kuo & Chiang, 2013), aggression (Greitemeyer & Sagioglou, 2016), smoking (Kuo & Chiang, 2013), risk-taking (Keshavarz et al., 2021), and poor decision-making (Suh & Flores, 2017). Based on these theoretical and empirical precedents, we proposed that increased relative deprivation should mediate the effect of sexual objectification on women’s self-regulation.

Dishonesty as a Behavioral Outcome of Sexual Objectification

Dishonesty refers to the chain of deceptive thoughts and actions that are often ethically questionable and lacking in integrity when pursuing a goal (Gerlach et al., 2019). The costs of dishonesty are high and wide-reaching. On the individual level, dishonesty may result in decreased self-esteem and increased high-arousal negative emotions, such as anger, guilt, and shame (Lee et al., 2019); meanwhile, dishonesty also has the social cost of broken relationships (Wang et al., 2011). These costs extend to larger scales with occupational fraud being found to cost an average of 5% of company revenues worldwide (Duch et al., 2020). Given these dire social and personal costs, examining factors that increase people’s dishonest tendencies and revealing the underlying psychological mechanisms are essential to create effective interventions. In the current research, we predicted that sexual objectification increases relative deprivation and reduces self-regulation, and that they play a crucial role in influencing the objectification–dishonesty link.

People are often tempted to behave dishonestly when given a chance to obtain benefits and fulfill their desires. However, they may be motivated to restrain their behaviors because they foresee the undesirable consequences of dishonesty, such as the punishments for lying, for example being labeled as untrustworthy (Curtis, 2021; Schweitzer et al., 2006), or breaking valuable relationships (Wang et al., 2011), and view them as outweighing the benefits of lying (Behnk et al., 2018). Therefore, people often try to self-regulate and keep their dishonest urges in check to avoid being punished or negatively judged. According to this premise, when a person has high self-regulation, they are less likely to behave dishonestly. In contrast, when a person’s self-regulation is low, they are more prone to dishonest behavior.

The prediction that reduced self-regulation increases dishonest behavior has received empirical support. For example, experimental studies have shown that higher self-regulating abilities directly decrease tendencies of general and academic dishonesty (Gotlib & Converse, 2010; Mead et al., 2009; Yu et al., 2017). Moreover, research has also found that low self-regulation could lead to financial dishonesty (e.g., fraud, tax avoidance; Khatwani & Goyal, 2019), unethical leadership behavior (e.g., engage in dictatorship, falsifying information; Joosten et al., 2014), and higher acceptance of infidelity (Ciarocco et al., 2012).

Altogether, existing theories and empirical findings allow us to predict that reduced self-regulation increases dishonesty. Our theoretical model explicates a pathway illustrating that sexual objectification increases relative deprivation and reduces self-regulation. Subsequently, sexually objectified individuals should be more likely to behave dishonestly. Thus, we hypothesized that relative deprivation and self-regulation serially mediate the effect of objectification on dishonesty.

Current Experiments

Prior ethical approval for the current research was granted by the Institutional Review Board of the authors’ university. We conducted two experiments to test the effect of sexual objectification on dishonest tendencies (Experiments 1 and 2) and the underlying psychological mechanism (Experiment 2). Specifically, we tested two hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1

Sexual objectification increases dishonest tendencies.

Hypothesis 2

Increased state relative deprivation and lowered state self-regulation serially mediate the effect of sexual objectification on dishonesty.

Experiment 1

Method

In Experiment 1, we tested whether sexual objectification increases dishonesty. Based on the existing research on sexual objectification (e.g., Karsay et al., 2018) and dishonesty (e.g., Gerlach et al., 2019), we expected a medium effect size for the current experiment (d = 0.5). Results of a G*power 3.1.9.2 power analysis (Faul et al., 2009) indicated that the study required 128 participants to detect a medium effect size (d = 0.5) and adequate power (80%) at the α = 0.05 level. Thus, we planned to recruit at least 64 participants for each condition.

Participants

Participants were American women recruited from CloudResearch, an online platform that aids researchers in collecting representative data (Eyal et al., 2022). At the start of the study, participants needed to pass a reCAPTCHA check to prevent bots from contaminating our data (Von Ahn et al., 2008). A total of 159 female participants completed this experiment for a small monetary reward. They were randomly assigned to either the sexual objectification or control condition. Nine participants were excluded from our analyses because they failed to pass the attention check. Keeping these participants in the analyses would not substantially influence the reported findings. The final sample consisted of 150 participants (Mage = 34.27; SD = 10.39). The racial composition of this sample was 68.0% White, 12.7% Black, 12.0% Hispanic, 3.3% Asian, and 4.0% other.

Procedure

Participants were informed that this experiment was about online first impressions. The experiment took around 10 min to complete and took place entirely on Qualtrics. After providing their informed consent, participants were exposed to the sexual objectification manipulation, which has been widely used in past studies (e.g., Poon & Jiang, 2020; Teng et al., 2015). Specifically, participants were first instructed to set up a simulated social media account by uploading a full-body portrait to our server, which they were told would be shared with an ostensible online male partner. We tried to make it resemble a real-life interaction on social media. The simulated social media page from this manipulation can be seen in more detail in Appendix 1 of the Supplementary Material. Participants were led to believe that their interaction partner on the simulated social media site was engaging in synchronous interaction with them, but in reality, the entire interaction was pre-programmed. There were no specific criteria for the image uploaded other than being required to include the participant’s full body. In addition, participants were prompted to write a short bio of at least 30 words to introduce themselves to their partners. Participants exchanged profiles with their partner and had the chance to view their partner’s portrait and carefully read their introduction. Then, our participants wrote down their first impression of their partner using at least 30 words, and were told that their partners were also writing their own first impression of the participant. Participants’ responses were validated based on their achievement of the minimum length for the bio and the first impression. Next, they were prompted to read their partner’s first impression of them. Participants’ sexual objectification experience was manipulated through their partner’s feedback. Those in the sexual objectification condition read the following (in part): “You have a gorgeous body, and the body proportion is absolutely perfect (especially those boobs). You have nice legs too, they are very sexy.” In contrast, participants in the control condition read the following (in part): “I can tell that you are a very communicative person after reading your self-introduction, and you sound very polite and knowledgeable as well. I am sure you get along with people around you easily, and they must be fortunate to find a friend like you.” Afterward, participants responded to four manipulation check questions. Finally, participants completed a hypothetical negotiation task to assess their dishonest tendencies (Piff et al., 2012). Participants were then thanked and debriefed. Specifically, participants were told that the entire interaction was not real, and was computer simulated. They were further informed of the true purpose of the experiment. Contact information of the investigator was also given to them so that they could ask any questions they might have.

Measures

Manipulation Checks

Participants responded to four items (“I feel more like a body rather than a real person,” “I feel as if my body and my identity are separate things,” “I feel I am viewed more like an object, rather than a human being,” and “It is only my body not my personality that caught the other’s attention”; 1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree). These items were adapted from previous studies (e.g., Poon & Jiang, 2020; Teng et al., 2015), and participants’ responses were averaged to check the effectiveness of the manipulation (α = 0.88).

Dishonesty

Participants were asked to imagine themselves in a situation where they must represent their company to negotiate a low-salary job with a potential candidate. The candidate desired to remain in the same position for at least 2 years and would accept a lower salary if they were verbally promised job stability. However, the participants knew that the vacancy was only a short-term position and the candidate’s employment would certainly be terminated after 6 months. However, no other suitable candidate was available at the moment, and the current applicant was not aware of this information. Participants were further informed that an end-of-year bonus would be granted if the negotiation was successful. In contrast, a failure to refill the position in time would negatively affect their annual appraisal. Participants then indicated their inclination (given as a percentage from 0 to 100%) to hide the true information from the candidate if he or she specifically asked about job security. This measure has been popularly adopted by researchers to measure state-level dishonesty (e.g., Clerke et al., 2018; Li et al., 2019; Piff et al., 2012; Poon et al., 2013). Their response would serve as a measure of dishonesty, with higher percentages reflecting greater dishonest tendencies.

Results

Manipulation Checks

Participants in the objectification condition (M = 5.21, SD = 1.28) indicated they felt more objectified compared to participants in the control condition (M = 3.82; SD = 1.88), t(148) = 5.28, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.86, 95% confidence interval (CI) of the mean difference [0.87 to 1.91]. Therefore, our sexual objectification manipulation was effective.

Dishonesty

We predicted that sexual objectification increases dishonesty. As predicted, participants in the objectification condition (M = 41.24, SD = 24.77) were more likely to hide the true information compared to participants in the control condition (M = 31.00, SD = 25.95), t(148) = 2.47, p = 0.015, Cohen’s d = 0.40, 95% CI of the mean difference [2.05 to 18.43].

Discussion

Experiment 1 provided initial support for our prediction that sexual objectification increases dishonesty, with participants in the sexual objectification condition having showed a higher tendency to lie during the negotiation task than participants in the control condition. In the current study, we advanced existing knowledge by offering the first experimental finding that sexual objectification increases dishonest tendencies. Although the finding of Experiment 1 was straightforward, the psychological mechanism underlying the effect of sexual objectification on dishonesty remained unclear. Thus, we conducted another experiment to address this issue. In addition, the manipulation of sexual objectification in this experiment relied on participants believing in the authenticity of the partner’s profile and response. This may have been influenced by information and materials included in the participants’ created profiles; for example, they may have included self-objectifying information or poorly lit photographs in which their bodies could not be clearly seen. It was desirable to adopt another paradigm to manipulate objectification and another measure to assess state-level dishonesty to increase the external validity of the findings. Therefore, in Experiment 2, we adopted a new manipulation and measure.

Experiment 2

In Experiment 2, we aimed to extend the findings of Experiment 1 by testing the psychological mechanism underlying the effect of sexual objectification on dishonesty. Specifically, we predicted that increased state relative deprivation and lowered state self-regulation would serially mediate the effect of sexual objectification on dishonesty. Importantly, these variables have all been demonstrated to be influenced at the state level in prior research (e.g., Ciarocco et al., 2012; Poon et al., 2013; Zhang & Zhang, 2016).

For Experiment 2, we opted for a different manipulation of sexual objectification to address potential confounds with that used in Experiment 1, such as the believability of the partner responses and the possibility that participants may have included self-objectifying information in their profiles. In addition, we hoped to enhance the external validity of the present research by utilizing a different manipulation of sexual objectification as this phenomenon may occur across many domains and contexts in real life. For example, instances of sexual objectification may vary along the lines of the controllability of the experience (e.g., targets of sexual objectification on a social media platform may log off or cease interactions with the perpetrator) and the nature of the relationship between the target and the perpetrator of sexual objectification (e.g., a stranger on a social media platform compared to a colleague). Thus, we adopted a new sexual objectification manipulation to account for some of these differences in the experiences of sexual objectification in real life. Further, we opted for a new measure of state dishonesty in Experiment 2. Given that dishonesty may occur through behaviors other than verbal deception, as described in the measure used in Experiment 1, we hoped to capture participants’ tendencies to carry out other forms of dishonest behavior. Thus, we adopted a new measure which asked participants about their tendencies to carry out various behaviors involving a lack of ethics and integrity beyond telling a lie.

Based on the results of Experiment 1, we expected a medium effect size in Experiment 2. Using Monte Carlo simulation (Schoemann et al., 2017), the power analysis revealed that 250 participants were required to detect a medium effect (rs = 0.3, SDs = 0.1) with 80% power. Thus, we planned to recruit at least 125 participants in each condition.

Method

Participants

Participants were American women recruited from CloudResearch. All passed a reCAPTCHA check before proceeding to the study materials. A total of 303 female participants completed this experiment for a small monetary reward. They were randomly assigned to either the sexual objectification or control condition. We excluded 24 participants from our analyses because they failed to pass the attention check. Keeping these participants in the analyses would not substantially influence the reported findings. The final sample consisted of 279 participants (Mage = 40.97; SD = 13.50; 10 unreported). The racial composition of the sample was 73.2.% White, 9.3% Asian, 8.9% Black, 5.9% Hispanic, and 2.6% other.

Procedure

Participants were informed that the experiment involved elements of imagination. This experiment took around 10 min to complete and took place on Qualtrics. Upon providing their informed consent, participants were exposed to the sexual objectification manipulation, which has been widely adopted in past studies (e.g., Poon & Jiang, 2020; Shepherd, 2019). Specifically, participants were asked to imagine themselves as a new employee at a company. Participants in the objectification condition were instructed to imagine themselves receiving appearance-related compliments from their colleagues, including, “Your skin tone and skin complexion are great as well. You also have an amazing butt. Your body shape looks very nice.” In contrast, participants in the control condition imagined themselves receiving neutral, nonappearance-related compliments, including, “You seem to be a sweet-tempered, energetic, and optimistic person. Your easy-going personality makes people feel comfortable talking with you and enjoy having conversations with you.” Next, participants completed the manipulation check items and well-validated measures assessing their state relative deprivation and state self-regulation.

Finally, participants completed the measure of dishonest tendencies. Compared to Experiment 1, participants in this experiment were required to react and indicate their dishonest tendencies in multiple scenarios. Although dishonesty is often thought of as verbal deception (as in Experiment 1), participants in this experiment may indicate their dishonest tendencies in a broader scope with reference to various types of dishonest behaviors across different contexts. After completing this measure, participants were thanked and debriefed, similar to Experiment 1.

Measures

Manipulation Checks

The same manipulation check items used in Experiment 1 were implemented to check the effectiveness of the sexual objectification manipulation in this experiment (α = 0.91).

Relative Deprivation

Participants completed a 5-item well-validated measure of state relative deprivation from previous studies (e.g., Callan et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2017). Participants rated their agreement with statements such as “I feel deprived when I think about what I have compared to what other people like me have” (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree). Responses were reverse-coded when necessary and averaged, with higher scores indicating greater feelings of relative deprivation (α = 0.80).

Self-Regulation

Participants also completed a 10-item measure of state self-regulation from past research (e.g., Ciarocco et al., 2012; Gailliot et al., 2012; Poon et al., 2020b), indicating how true they felt each statement was (1 = not true; 7 = very true). A sample item is “If I were tempted by something right now, it would be very difficult to resist.” The collected responses were reverse-coded when necessary and averaged to index state self-regulation (α = 0.88).

Dishonesty

Participants’ dishonest tendencies were examined using a measure adapted from prior research (Piff et al., 2012). This measure has also been frequently adopted in past research to assess dishonest tendencies (e.g., Clerke et al., 2018; Poon et al., 2013; Tang et al., 2018). Participants imagined themselves as the main character in various scenarios and indicated their likelihood of performing certain dishonest behaviors to satisfy their self-interest. For example, in one scenario, participants were asked to imagine that they found a wallet unattended on the street with $2000 in it. Neither CCTV nor any bystanders were nearby. Then, they would indicate their tendency to take the money instead of handing it in (1 = very unlikely; 7 = very likely). Participants’ responses on various items (e.g., taking expensive office stationery for personal use, taking undeserved money from the petty cash drawer, submitting a blank document to boss and claiming it was an unintentional mistake to buy more time to complete the document, and falsifying a resume for a job application) were averaged to index their dishonesty (α = 0.72).

Results

Manipulation Checks

Participants in the objectification condition (M = 6.04, SD = 1.00) indicated stronger feelings of objectification compared to their counterparts in the control condition (M = 2.65; SD = 1.45), t(277) = 22.83, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 2.73, 95% CI of the mean difference [3.11 to 3.69]. Therefore, our sexual objectification manipulation was effective.

Relative Deprivation and Self-Regulation

We predicted that sexual objectification increases relative deprivation and decreases self-regulation. As predicted, participants in the objectification condition (M = 3.32, SD = 1.26) demonstrated stronger feelings of relative deprivation than participants in the control condition did (M = 2.87; SD = 1.12), t(277) = 3.13, p = 0.002, Cohen’s d = 0.37, 95% CI of the mean difference [0.17 to 0.73]. Moreover, sexually objectified participants (M = 5.07, SD = 1.26) reported lower self-regulation than control participants did (M = 5.61, SD = 1.08), t(277) = − 3.83, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = -0.46, 95% CI of the mean difference [− 0.82 to − 0.26].

Dishonesty

We predicted that sexual objectification increases dishonesty. As predicted, participants in the objectification condition (M = 3.28, SD = 1.16) reported higher dishonest tendencies compared to participants in the control condition (M = 2.97, SD = 0.97), t(277) = 2.40, p = 0.017, Cohen’s d = 0.29, 95% CI of the mean difference [0.06 to 0.56].

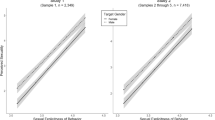

Serial Mediation Analysis

We predicted that relative deprivation and self-regulation serially mediate the effect of sexual objectification on dishonesty. We conducted a bootstrapping serial mediation analysis with 5000 iterations using the PROCESS macro (Model 6; Hayes, 2013). The conditions were coded either as 1 (objectification condition) or − 1 (control condition). The results showed that this serial mediation model could explain 8.90% of variance in dishonesty.Footnote 1 Moreover, a significant serial mediation effect through relative deprivation followed by self-regulation was found because the 95% CI did not include zero (0.001 to 0.05; see Fig. 1). The effect of sexual objectification on dishonesty became statistically insignificant after controlling for the influences of relative deprivation and self-regulation (p = 0.177). Altogether, these findings provided direct empirical evidence supporting the prediction that the effect of sexual objectification on dishonesty is serially mediated by relative deprivation and self-regulation.

General Discussion

Honesty is one of the most important virtues in human interactions, with fables such as The Boy Who Cried Wolf educating children from a young age about the morality of telling the truth and the punishments of lying. Despite the importance society places on honesty, we often find ourselves living in a world filled with lies; people around us might behave dishonestly or fail to live up to a promise, which could cause irretrievable damage to social relationships (Wang et al., 2011). The motives behind dishonest behavior and its underlying mechanisms are often complicated. Researching beyond the effect of personality traits or known situational factors, we investigated whether sexual objectification, a highly prevalent form of interpersonal maltreatment that women often experience, may promote dishonesty through increased relative deprivation and reduced self-regulation.

The results of the current research provide converging support to our predictions. We found that participants who experienced sexual objectification reported higher relative deprivation, lower self-regulation, and stronger dishonest tendencies than those who did not experience objectification. Importantly, we identified one potential psychological mechanism underlying the effect of sexual objectification on dishonesty by showing the serial mediation effect of relative deprivation and self-regulation on the objectification—dishonesty link.

Implications of the Current Research

Our experiments advance existing theories and knowledge in three ways, while also providing some important clinical implications. First, our research pioneers the first experimental evidence, to our knowledge, showing that sexual objectification increases dishonesty, enhancing understanding of the adverse outcomes caused by sexual objectification. Given the high prevalence of sexual objectification in women’s lives, it is essential to thoroughly investigate its outcomes to facilitate victims’ healthy coping following an objectification episode. For instance, previous clinical and experimental research has shown that sexual objectification leads to eating disorder symptoms (Holmes & Johnson, 2017), aggression (Poon & Jiang, 2020), alcohol use (Baildon et al., 2021), and sexual risk-taking behavior (Drake et al., 2021). Although these outcomes cause immediate- or long-term harm to the objectified victim and others around them, dishonesty is a phenomenon that is more commonly observed compared to engagement in addictive behaviors. Dishonesty may also be an important factor in promoting these other outcomes; for example, dishonesty has been demonstrated to be common among those with substance abuse problems and eating disorders as a way to minimize perceptions of their problem and protect themselves (Farber, 2020). In addition, instead of affecting one’s physical and mental health, dishonesty also has dire consequences in interpersonal relationships and could even threaten societal well-being. Therefore, the social impacts of sexual objectification on victims could also be interpreted through the current findings.

Second, our research also discovers risk factors that motivate people to behave dishonestly. Previous research has shown that dishonesty can be predicted by high acceptability of lying (McLeod & Genereux, 2008), low self-esteem (Dai et al., 2002), and strong psychopathy (Muñoz & De Los Reyes, 2021). Moreover, victims of various forms of maltreatment, such as unfairness (Zitek et al., 2010), ostracism (Poon et al., 2013), and bullying (Hasebe et al., 2021), are more likely to behave dishonestly. The present findings elaborate on this by identifying sexual objectification as another predictor of dishonest behavior. Our findings could encourage practitioners to look for ways to prevent dishonest behavior through mitigating the effects of sexual objectification.

Third, in the current experiments, we identified one potential psychological mechanism underlying the effect of sexual objectification on dishonesty, which carries both practical and theoretical implications. Our research demonstrated that victims of sexual objectification are more likely to become dishonest due to the perception of relative deprivation and a subsequent reduction in self-regulation. By revealing the underlying factors that drive sexually objectified women’s dishonesty, practitioners can devise intervention programs to reduce these tendencies, and perhaps support healthier and more productive coping responses. Future research may test whether interventions that focus on reducing objectified women’s relative deprivation and/or increasing their self-regulation may weaken their dishonesty.

Given the extensiveness of negative outcomes of sexual objectification, we highlight the importance of reducing the prevalence of sexual objectification experienced by women. Although individual-level resistance methods have been suggested, such as wearing loose-fitting clothes (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997), past studies have found that women may be objectified regardless of their clothing (Hollett et al., 2022) or whether they possess an average or ideal body type (Gervais et al., 2012). Thus, taken together with our findings on the consequences of sexual objectification, this emphasizes the need for culture-level changes to reduce the experience of sexual objectification (see Szymanski & Carr, 2011, for a review).

More broadly, the proposed theoretical model that sexual objectification leads to increased relative deprivation and reduced self-regulation may carry implications beyond dishonesty. When women are frustrated after episodes of sexual objectification, they may possess strong feelings of relative deprivation, thus losing or selectively reducing control in suppressing their maladaptive urges in general. This speculation is consistent with previous studies that have shown sexual objectification increases women’s aggressive responses, especially toward the perpetrator (e.g., Burnay et al., 2019; Poon & Jiang, 2020; Sáez et al., 2019). The aggressive behaviors may function as a way to yield benefits for the victim, such as the feeling of relief (Bushman et al., 2001). Similarly, previous findings have shown that sexual objectification increases an array of impulsive behaviors, such as alcohol consumption (Baildon et al., 2021), binge eating (Buchanan et al., 2013), and risky sexual decision-making (Drake et al., 2021). The increase in relative deprivation and lowered self-regulation may also serve as the underlying mechanisms between sexual objectification and other impulsive behaviors; thus, interventions addressing these mediators may mitigate other maladaptive impulsive behaviors as well. These speculations await further research evidence.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Several limitations within the current experiments may provide a guide for future research. First, we must recognize the limitations of the methodology used for the present research. The online administration of both experiments may limit the control over the manipulations used. Although we utilized attention checks and other validation strategies for participants’ responses, there may be confounds that arose as a result of the online administration of the present experiments. Moreover, the change in sexual objectification manipulation paradigms and dishonesty measures used between Experiment 1 and 2 may bring into question the validity of our findings. While the change in sexual objectification manipulation in Experiment 2 was done to address potential confounds with that used in Experiment 1 as well as to avoid the need for deception, this change may have influenced the internal validity of the present research, constraining our ability to draw conclusions. Further, the dishonesty measures used in Experiments 1 and 2 assess different conceptions of dishonesty. Although we aimed to capture dishonest tendencies more broadly, this difference may suggest that the measure used in Experiment 2 pertains less to state dishonesty, instead measuring a distinct related construct. Thus, it is ideal for future research to adopt methods which offer more control and consistency in measuring dishonesty and manipulating sexual objectification, while avoiding deception. In doing so, future research may help to enhance the validity and reliability of the present findings.

Second, although we revealed that increased relative deprivation and reduced self-regulation serially mediate the relationship between sexual objectification and dishonesty, other undiscovered psychological processes may also potentially explicate the objectification—dishonesty link. Previous research has suggested that those with social anxiety (Orr & Moscovitch, 2015) and deprived self-esteem (Liang et al., 2020) also show higher tendencies to tell lies or cheat. Future research may test whether a potential increase in social anxiety or decrease in self-esteem following sexual objectification may account for the effect of sexual objectification on dishonesty.

Third, we did not consider the role of personality factors in influencing the effect of sexual objectification on dishonesty in our experiments. Previous studies have indicated that people with low emotional intelligence (Huffman, 2019) and high neuroticism (Hart et al., 2020) tend to behave more dishonestly following interpersonal maltreatment. In contrast, people high in agreeableness and conscientiousness (Giluk & Postlethwaite, 2015) are less likely to behave dishonestly in similar situations. A conducive next step would be adopting a person–situation approach by testing whether various personality factors may potentially strengthen or weaken the effect of sexual objectification on dishonesty.

Fourth, the consequences of sexual objectification may vary according to situational cues and context (Baildon et al., 2021; Szymanski et al., 2011). In the current experiments, we only manipulated the presence or absence of sexual objectification episodes, neglecting the nuances of such experiences along different dimensions, including motive, severity, and relationship between the target and perpetrator. It remains unknown whether these factors may influence the appearance of dishonest tendencies following sexual objectification. Further nuance exists among the targets of sexual objectification. For example, some studies have found that individuals may enjoy sexualization or attempt to elicit body gaze (Hollett et al., 2022; Liss et al., 2011), whereas other studies have found that targets’ beliefs, such as sex-is-power beliefs and benevolent sexism, moderated the effects of sexual objectification (Gervais et al., 2016; Jiang et al., 2022). Therefore, individual differences may exist in the perception of relative deprivation following instances of sexual objectification. More research evidence is needed to explore potential moderating effects of varying contexts of sexual objectification and individual differences. Addressing this question could aid future advances in current knowledge and theories. Moreover, this additional evidence could contribute to the design of effective interventions for victims of sexual objectification according to individual differences.

Finally, in the present research, only American women participated in the experiments, neglecting potential cultural differences in responses to sexual objectification. Fredrickson and Roberts (1997) acknowledged cultural differences in women’s experiences of sexual objectification. However, past research has had mixed results when looking at cultural differences in the nature and prevalence of sexual objectification (Loughnan et al., 2015; Wollast et al., 2018). Further research is required to investigate possible cultural differences among the consequences of sexual objectification for the target to enhance our understanding of this phenomenon.

Notes

We conducted an additional simple mediation analysis (Model 4; Hayes, 2013) to examine whether self-regulation mediated the effect of sexual objectification on dishonesty. The results showed that this simple mediation model could explain 7.73% of variance in dishonesty. Moreover, a significant simple mediation effect through self-regulation was found because the 95% CI did not include zero (0.02 to 0.10). The results revealed that the serial mediation model reported in the main document could explain more variance in dishonesty than the simple mediation model could.

References

Agbaria, Q. (2021). Internet addiction and aggression: The mediating roles of self-control and positive affect. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 19, 1227–1242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-019-00220-z

Baildon, A. E., Eagan, S. R., Christ, C. C., Lorenz, T., Stoltenberg, S. F., & Gervais, S. J. (2021). The sexual objectification and alcohol use link: The mediating roles of self-objectification, enjoyment of sexualization, body shame, and drinking motives. Sex Roles, 85, 190–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01213-2

Bandura, A. (1999). Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 3, 193–209. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0303_3

Baumeister, R. F., & Vohs, K. D. (2016). Strength model of self-regulation as limited resource: Assessment, controversies, update. In J. M. Olsen & M. P. Zanna (Eds.), Advances in experimental social psychology (pp. 67–127). Elsevier Academic Press.

Behnk, S., Barreda-Tarrazona, I., & García-Gallego, A. (2018). Punishing liars—How monitoring affects honesty and trust. PLoS ONE, 13, e0205420. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205420

Brinkman, B. G., & Rickard, K. M. (2009). College students’ descriptions of everyday gender prejudice. Sex Roles, 61, 461–475. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-009-9643-3

Buchanan, N. T., Bluestein, B. M., Nappa, A. C., Woods, K. C., & Depatie, M. M. (2013). Exploring gender differences in body image, eating pathology, and sexual harassment. Body Image, 10(3), 352–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2013.03.004

Burnay, J., Bushman, B. J., & Larøi, F. (2019). Effects of sexualized video games on online sexual harassment. Aggressive Behavior, 45, 214–223. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21811

Burraston, B., Watts, S. J., McCutcheon, J. C., & Province, K. (2019). Relative deprivation, absolute deprivation, and homicide: Testing an interaction between income inequality and disadvantage. Homicide Studies, 23, 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088767918782938

Bushman, B. J., Baumeister, R. F., & Phillips, C. M. (2001). Do people aggress to improve their mood? Catharsis beliefs, affect regulation opportunity, and aggressive responding. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81, 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.81.1.17

Callan, M. J., Ellard, J. H., Will Shead, N., & Hodgins, D. C. (2008). Gambling as a search for justice: Examining the role of personal relative deprivation in gambling urges and gambling behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(11), 1514–1529. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167208322956

Callan, M. J., Shead, N. W., & Olson, J. M. (2011). Personal relative deprivation, delay discounting, and gambling. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101, 955–973. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024778

Ciarocco, N. J., Echevarria, J., & Lewandowski, G. W., Jr. (2012). Hungry for love: The influence of self-regulation on infidelity. Journal of Social Psychology, 152, 61–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2011.555435

Clapp, A. R., & Syed, M. (2021). Self-objectification and sexual satisfaction: A preregistered test of the replicability and robustness of Calogero & Thompson (2009) in a sample of U.S. women. Body Image, 39, 16–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2021.05.011

Clerke, A. S., Brown, M., Forchuk, C., & Campbell, L. (2018). Association between social class, greed, and unethical behaviour: A replication study. Collabra: Psychology, 4(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.1525/collabra.166

Curtis, D. A. (2021). You liar! Attributions of lying. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 40(4), 504–523. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X21999692

Dai, Y., Nolan, R. F., & White, B. (2002). Response to moral choices as a function of self-esteem. Psychological Reports, 90, 907–912. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.2002.90.3.907

Dennison, C. R., & Swisher, R. R. (2019). Postsecondary education, neighborhood disadvantage, and crime: An examination of life course relative deprivation. Crime & Delinquency, 65(2), 215–238. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128717753115

Drake, H. P., Chenneville, T., Rodriguez, L., Suite, B., & Onufrak, J. (2021). Sexual objectification as a predictor of sexual risk tolerance. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 33, 273–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538720.2021.1886213

Duch, R. M., Laroze, D., & Zakharov, A. (2020). The moral cost of lying. Nuffield College Centre for Experimental Social Sciences (CESS) Working Paper, 1–80. https://www.raymondduch.com/files/The-moral-cost-of-lying_April-2020.pdf

Dvir, M., Kelly, J. R., Tyler, J. M., & Williams, K. D. (2021). I’m up here! Sexual objectification leads to feeling ostracized. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 121, 332–353. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000328

Eyal, P., David, R., Andrew, G., Zak, E., & Ekaterina, D. (2022). Data quality of platforms and panels for online behavioral research. Behavior Research Methods, 54, 1643–1662. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-021-01694-3

Farber, B. A. (2020). Disclosure, concealment, and dishonesty in psychotherapy: A clinically focused review. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 76, 251–257. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22891

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41, 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T. A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experience and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 173–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x

Gailliot, M. T., Gitter, S. A., Baker, M. D., & Baumeister, R. F. (2012). Breaking the rules: Low trait or state self-control increases social norm violations. Psychology, 3, 1074–1083. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2012.312159

Gerlach, P., Teodorescu, K., & Hertwig, R. (2019). The truth about lies: A meta-analysis on dishonest behavior. Psychological Bulletin, 145, 1–44. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000174

Gervais, S. J., Wiener, R. L., Allen, J., Farnum, K. S., & Kimble, K. (2016). Do you see what I see? The consequences of objectification in work settings for experiencers and third party predictors. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 16(1), 143–174. https://doi.org/10.1111/asap.12118

Gervais, S. J., Vescio, T. K., & Allen, J. (2012). When are people interchangeable sexual objects? The effect of gender and body type on sexual fungibility. British Journal of Social Psychology, 51(4), 499–513. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8309.2010.02016.x

Gillebaart, M. (2018). The ‘operational’ definition of self-control. Frontier in Psychology, 9, 1231. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01231

Giluk, T. L., & Postlethwaite, B. E. (2015). Big Five personality and academic dishonesty: A meta-analytic review. Personality and Individual Differences, 72, 59–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.08.027

Gotlib, T., & Converse, P. (2010). Dishonest behavior: The impact of prior self-regulatory exertion and personality. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 40, 3169–3191. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2010.00696.x

Greitemeyer, T., & Sagioglou, C. (2016). Subjective socioeconomic status causes aggression: A test of the theory of social deprivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 111, 178–194. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000058

Hagger, M. S., & Chatzisarantis, N. L. D. (2013). The strength model of self-control: Recent advances and implications for public health. In P. A. Hall (Ed.), Social neuroscience and public health: Foundations for the science of chronic disease prevention (pp. 123–139). Springer Science + Business Media.

Hart, C. L., Lemon, R., Curtis, D. A., & Griffith, J. D. (2020). Personality traits associated with various forms of lying. Psychological Studies, 65, 239–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-020-00563-x

Hasebe, Y., Harbke, C. R., & Sorkhabi, N. (2021). Peer bullies and victim’s perceptions of moral transgression versus morally-aimed dishonesty. Critical Questions in Education, 12, 40–55.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Routledge: Guilford Press.

Heflick, N. A., & Goldenberg, J. L. (2014). Seeing eye to body: The literal objectification of women. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23, 225–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721414531599

Holland, E., Koval, P., Stratemeyer, M., Thomson, F., & Haslam, N. (2017). Sexual objectification in women’s daily lives: A smartphone ecological momentary assessment study. British Journal of Social Psychology, 56(2), 314–333. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12152

Hollett, R. C., Rogers, S. L., Florido, P., & Mosdell, B. (2022). Body gaze as a marker of sexual objectification: A new scale for pervasive gaze and gaze provocation behaviors in heterosexual women and men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51, 2759–2780. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-022-02290-y

Holmes, S. C., & Johnson, D. M. (2017). Applying objectification theory to the relationship between sexual victimization and disordered eating. The Counseling Psychologist, 45(8), 1091–1114. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000017745977

Huffman, J. A. (2019). I cannot tell a lie: Emotional intelligence as a predictor of deceptive behavior. Inquiry Journal, 10. https://scholars.unh.edu/inquiry_2019/10

Jiang, Y., Wong, N.H.-L., Chan, Y. C., & Poon, K.-T. (2022). Lay awake with a racing mind: The associations between sexual objectification, insomnia, and affective symptoms. Journal of Affective Disorders, 299, 359–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.12.031

Joosten, A., van Dijke, M., Van Hiel, A., & De Cremer, D. (2014). Being “in control” may make you lose control: The role of self-regulation in unethical leadership behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 121, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1686-2

Karsay, K., Knoll, J., & Matthes, J. (2018). Sexualizing media use and self-objectification: A meta-analysis. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 42, 9–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684317743019

Kawakami, K., & Dion, K. L. (1993). The impact of salient self-identities on relative deprivation and action intentions. European Journal of Social Psychology, 23, 525–540. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420230509

Keshavarz, S., Coventry, K. R., & Fleming, P. (2021). Relative deprivation and hope: Predictors of risk behavior. Journal of Gambling Studies, 37, 817–835. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-020-09989-4

Khatwani, R. K., & Goyal, V. (2019). Predictors of financial dishonesty: Self control opportunity attitudes. Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal, 23(5), 1–13.

Kim, H., Callan, M. J., Gheorghiu, A. I., & Matthews, W. J. (2017). Social comparison, personal relative deprivation, and materialism. British Journal of Social Psychology, 56, 373–392. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12176

Kozee, H. B., Tylka, T. L., Augustus-Horvath, C. L., & Denchik, A. (2007). Development and psychometric evaluation of the interpersonal sexual objectification scale. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 31, 176–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00351.x

Kuo, C.-T., & Chiang, T.-L. (2013). The association between relative deprivation and self-rated health, depressive symptoms, and smoking behavior in Taiwan. Social Science & Medicine, 89, 39–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.04.015

Laplanche, J., & Pontalis, J.-B. (2018). Pleasure principle: The language of psychoanalysis. Routledge.

Lee, J. J., Hardin, A. E., Parmar, B., & Gino, F. (2019). The interpersonal costs of dishonesty: How dishonest behavior reduces individuals’ ability to read others’ emotions. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 148, 1557–1574. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000639

LeMoncheck, L. (1985). Dehumanizing Women: Treat persons as sex objects. Rowman & Littlefield.

Li, H., Wang, X., Guo, Y., Chen, Z., & Teng, F. (2019). Air pollution predicts harsh moral judgment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16, 2276. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16132276

Liang, Y., Liu, L., Tan, X., Dang, J., Li, C., & Gu, Z. (2020). The moderating effect of general system justification on the relationship between unethical behavior and self-esteem. Self and Identity, 19, 140–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2018.1541328

Liss, M., Erchull, M. J., & Ramsey, L. R. (2011). Empowering or oppressing? Development and exploration of the Enjoyment of Sexualization Scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37, 55–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167210386119

Liu, H., & Li, H. (2020). Self-control modulates the behavioral response of interpersonal forgiveness. Frontier in Psychology, 11, 472. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00472

Loughnan, S., Baldissarri, C., Spaccatini, F., & Elder, L. (2017). Internalizing objectification: Objectified individuals see themselves as less warm, competent, moral, and human. British Journal of Social Psychology, 56, 217–232. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12188

Loughnan, S., Fernandez-Campos, S., Vaes, J., Anjum, G., Aziz, M., Harada, C., Holland, E., Singh, I., Puvia, E., & Tsuchiya, K. (2015). Exploring the role of culture in sexual objectification: A seven nations study. International Review of Social Psychology, 28, 125–152.

McLeod, B. A., & Genereux, R. L. (2008). Predicting the acceptability and likelihood of lying: The interaction of personality with type of lie. Personality and Individual Differences, 45, 591–596. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.06.015

Mead, N. L., Baumeister, R. F., Gino, F., Schweitzer, M. E., & Ariely, D. (2009). Too tired to tell the truth: Self-control resource depletion and dishonesty. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45, 594–597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.02.004

Miller, H. V., Barnes, J. C., & Beaver, K. M. (2011). Self-control and health outcomes in a nationally representative sample. American Journal of Health Behavior, 35(1), 15–27. https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.35.1.2

Muñoz, M. E., & De Los Reyes, S. (2021). The Dark Triad and honesty rules in romantic relationships. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02171-y

Nussbaum, M. C. (1999). Sex and social justice. Oxford University Press.

Orr, E. M. J., & Moscovitch, D. A. (2015). Blending in at the cost of losing oneself: Dishonest self-disclosure erodes self-concept clarity in social anxiety. Journal of Experimental Psychopathology, 6, 278–296. https://doi.org/10.5127/jep.044914

Piff, P. K., Stancato, D. M., Côté, S., Mendoza-Denton, R., & Keltner, D. (2012). Higher social class predicts increased unethical behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 109, 4086–4091. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1118373109

Poon, K.-T., Chen, Z., & DeWall, C. N. (2013). Feeling entitled to more: Ostracism increases dishonest behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39, 1227–1239. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167213493187

Poon, K. T., Chen, Z., Teng, F., & Wong, W. Y. (2020a). The effect of objectification on aggression. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 87, 103940. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2019.103940

Poon, K. T., & Jiang, Y. (2020). Sexual objectification increases retaliatory aggression. Aggressive Behavior, 46, 291–304. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21889

Poon, K. T., Jiang, Y., & Teng, F. (2020b). Putting oneself in someone’s shoes: The effect of observing ostracism on physical pain, social pain, negative emotion, and self-regulation. Personality and Individual Differences, 166, 110217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110217

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55, 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Sáez, G., Valor-Segura, I., & Expósito, F. (2019). Interpersonal sexual objectification experiences: Psychological and social well-being consequences for women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34, 741–762. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260516645813

Schoemann, A. M., Boulton, A. J., & Short, S. D. (2017). Determining power and sample size for simple and complex mediation models. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 8, 379–386. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550617715068

Schweitzer, M. E., Hershey, J. C., & Bradlow, E. T. (2006). Promises and lies: Restoring violated trust. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 101, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2006.05.005

Shepherd, L. (2019). Responding to sexual objectification: The role of emotions in influencing willingness to undertake different types of action. Sex Roles, 80, 25–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-018-0912-x

Sim, A. Y., Lim, E. X., Forde, C. G., & Cheon, B. K. (2018). Personal relative deprivation increases self-selected portion sizes and food intake. Appetite, 121, 268–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2017.11.100

Smith, H. J., & Pettigrew, T. F. (2014). The subjective interpretation of inequality: A model of the relative deprivation experience. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 8, 755–765. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12151

Smith, H. J., Pettigrew, T. F., Pippin, G. M., & Bialosiewicz, S. (2012). Relative deprivation: A theoretical and meta-analytic review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 16, 203–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868311430825

Stephens, J. M. (2018). Bridging the divide: The role of motivation and self-regulation in explaining the judgment-action gap related to academic dishonesty. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 246. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00246

Suh, H. N., & Flores, L. Y. (2017). Relative deprivation and career decision self-efficacy: Influences of self-regulation and parental educational attainment. Career Development Quarterly, 65, 145–158. https://doi.org/10.1002/cdq.12088

Szymanski, D. M., & Carr, E. R. (2011). Underscoring the need for social justice initiatives concerning the sexual objectification of women. The Counseling Psychologist, 39, 164–170.

Szymanski, D. M., Moffitt, L. B., & Carr, E. R. (2011). Sexual objectification of women: Advances to theory and research. Counseling Psychologist, 39, 6–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000010378402

Tang, T.L.-P., Sutarso, T., Ansari, M. A., Lim, V. K., Teo, T. S., Arias-Galicia, F., Garber, I. E., Chiu, R.K.-K., Charles-Pauvers, B., Luna-Arocas, R., Vlerick, P., Akande, A., Allen, M. W., Al-Zubaidi, A. S., Borg, M. G., Cheng, B.-S., Correia, R., Du, L., Garcia de la Torre, C., & Adewuyi, M. F. (2018). Monetary intelligence and behavioral economics: The Enron effect—love of money, corporate ethical values, Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), and dishonesty across 31 geopolitical entities. Journal of Business Ethics, 148, 919–937. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2942-4

Teng, F., Chen, Z., Poon, K.-T., & Zhang, D. (2015). Sexual objectification pushes women away: The role of decreased likability. European Journal of Social Psychology, 45, 77–87. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2070

Teng, F., & Poon, K.-T. (2020). Body surveillance predicts young Chinese women’s social anxiety: Testing a mediation model. Journal of Gender Studies, 29, 623–635. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2020.1728523

Triana, M. D. C., Jayasinghe, M., Pieper, J. R., Delgado, D. M., & Li, M. (2019). Perceived workplace gender discrimination and employee consequences: A meta-analysis and complementary studies considering country context. Journal of Management, 45, 2419–2447. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206318776772

Troll, E. S., Friese, M., & Loschelder, D. D. (2021). How students’ self-control and smartphone-use explain their academic performance. Computers in Human Behavior, 117, 106624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106624

Vaes, J., Paladino, P., & Puvia, E. (2011). Are sexualized women complete human beings? Why men and women dehumanize sexually objectified women. European Journal of Social Psychology, 41(6), 774–785. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.824

Von Ahn, L., Maurer, B., McMillen, C., Abraham, D., & Blum, M. (2008). reCAPTCHA: Human-based character recognition via web security measures. Science, 321, 1465–1468. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1160379

Wang, C. S., Leung, A.K.-Y., See, Y. H. M., & Gao, X. Y. (2011). The effects of culture and friendship on rewarding honesty and punishing deception. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47, 1295–1299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2011.04.011

Wollast, R., Puvia, E., Bernard, P., Tevichapong, P., & Klein, O. (2018). How sexual objectification generates dehumanization in Western and Eastern cultures: A comparison between Belgium and Thailand. Swiss Journal of Psychology, 77, 69–82. https://doi.org/10.1024/1421-0185/a000209

Xie, X., Wang, Y., Wang, P., Zhao, F., & Lei, L. (2018). Basic psychological needs satisfaction and fear of missing out: Friend support moderated the mediating effect of individual relative deprivation. Psychiatry Research, 268, 223–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.07.025

Yu, H., Glanzer, P. L., Sriram, R., Johnson, B. R., & Moore, B. (2017). What contributes to college students’ cheating? A study of individual factors. Ethics & Behavior, 27(5), 401–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2016.1169535

Zhang, H., Deng, W., & Wei, L. (2020). Individual-based relative deprivation as a response to interpersonal help: The roles of status discrepancy and type of help. British Journal of Social Psychology, 59, 329–346. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12345

Zhang, H., & Zhang, W. (2016). Materialistic cues boosts personal relative deprivation. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1236. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01236

Zitek, E. M., Jordan, A. H., Monin, B., & Leach, F. R. (2010). Victim entitlement to behave selfishly. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98, 245–255. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017168

Funding

This research was supported by the Hong Kong Research Grants Council’s General Research Fund (18611121) and the Education University of Hong Kong’s Departmental Research Grant (E0475).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

The research was conducted in accord with APA ethical standards. Ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board of the authors’ university was obtained.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Poon, KT., Lai, HS. & Chan, R.S.W. The Effect of Sexual Objectification on Dishonesty. Arch Sex Behav 52, 1617–1629 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-023-02560-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-023-02560-3