Abstract

In the nationally representative General Social Survey, U.S. Adults (N = 33,380) in 2000–2012 (vs. the 1970s and 1980s) had more sexual partners, were more likely to have had sex with a casual date or pickup or an acquaintance, and were more accepting of most non-marital sex (premarital sex, teen sex, and same-sex sexual activity, but not extramarital sex). The percentage who believed premarital sex among adults was “not wrong at all” was 29 % in the early 1970s, 42 % in the 1980s and 1990s, 49 % in the 2000s, and 58 % between 2010 and 2012. Mixed effects (hierarchical linear modeling) analyses separating time period, generation/birth cohort, and age showed that the trend toward greater sexual permissiveness was primarily due to generation. Acceptance of non-marital sex rose steadily between the G.I. generation (born 1901–1924) and Boomers (born 1946–1964), dipped slightly among early Generation X’ers (born 1965–1981), and then rose so that Millennials (also known as Gen Y or Generation Me, born 1982–1999) were the most accepting of non-marital sex. Number of sexual partners increased steadily between the G.I.s and 1960s-born GenX’ers and then dipped among Millennials to return to Boomer levels. The largest changes appeared among White men, with few changes among Black Americans. The results were discussed in the context of growing cultural individualism and rejection of traditional social rules in the U.S.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Americans born before 1950 can recall a time when sex outside of marriage was taboo—it may have happened, but it was rarely discussed. In the 1950s and earlier, men and women rarely lived together before marriage, unmarried women who bore children were shunned, and homosexuality was considered shameful. In more recent times and among more recent generations, however, Americans are presumably more accepting of sexual activity outside of marriage and more likely to participate in it.

But are sexual behavior and attitudes really that different now than they once were? Perhaps any appearance of generational change lies in the biased perceptions of older adults, who prefer to forget their own youthful behaviors (e.g., Trzesniewski & Donnellan, 2010). Or perhaps cultural products such as music, TV, and movies provide a false picture of increased sexual permissiveness in recent years. This is the “nothing has really changed” argument and, if it is true, nationally representative surveys would show little change in sexual behavior and attitudes (consistent with the conclusions of at least some studies (e.g., Monto & Carey, 2014). Alternatively, behavior and attitudes may have undergone significant shifts as American culture became more sexually permissive.

If sexual behavior and attitudes have changed, a second, equally important, question is the mechanism behind that change. Populations change over time in three ways: Time period (a cultural change that affects people of all ages), generation/birth cohort (a cultural change primarily affecting young people that is retained with age), and age (developmental effects) Schaie, 1965; Yang, 2008).Footnote 1 This invites the question: Have sexual behavior and attitudes changed because people of all ages and generations changed at the same time (a time period effect), because new generations entered the survey and older generations exited (a generational or cohort effect), or because the American population has aged (a developmental effect)? Until recently, it was difficult to separate the effects of time period, generation, and age because each variable is a function of the other two and thus cannot be simultaneously entered into a regression equation. However, recently introduced mixed-effects models allow the separation of the three effects (e.g., Yang, 2008). These questions are particularly important for sexual attitudes and behavior, as they may help determine whether, for example, parents and adolescents will experience a significant generation gap in their views around sexuality, which can affect adolescents’ sexual behavior (e.g., Coley, Lombardi, Lynch, Mahalik, & Sims, 2013). A time period effect would suggest little difference between the attitudes of parents and adolescents, whereas a generational effect would mean a larger difference.

The research literature and popular conceptions converge on the existence of a “sexual revolution” during the 1960s and 1970s, primarily involving the Baby Boomer generation (born 1945–1964) embracing more sexually permissive attitudes and behaviors than previous generations did (e.g., Singh, 1980; Smith, 1990; Walsh, 1989). Generation X (born 1965–1981) appeared to continue this trend, with more acceptance of premarital sex, a younger age at first intercourse, and a high teen pregnancy rate (e.g., Howe & Strauss, 1993; Wells & Twenge, 2005). However, popular conceptions and research evidence on the Millennials (also known as Gen Y or Generation Me, born 1982–1999) have yielded an unclear picture. Millennials’ rates of adolescent sexual activity and teen pregnancy are lower than GenX’ers’ were (Eaton et al., 2011), with some even observing a “Millennial sexual counterrevolution” characterized by virginity pledges and modest dress (Howe & Strauss, 2000). In contrast, others have contended that Millennials ushered in a “hookup culture” of sex unconnected to commitment (Stepp, 2007), with fundamental shifts in young adults’ dating practices toward “friends with benefits” and other arrangements (Bogle, 2007). However, others have contended that claims of a new “hookup culture” have been overblown, with few generational differences in behavior among those who attended college (Monto & Carey, 2014). Time period effects are also uncertain; for example, did the “sexual revolution” end after the 1970s, or did attitudes and behaviors continue to change after the 1980s? Did the AIDS crisis of the 1980s and 1990s lead to Americans having sex with fewer partners? To answer these questions, it would be beneficial to empirically examine shifts in sexual attitudes and behaviors in large representative samples, particularly since the 1990s and among more recent generations, and to separate the effects of time period, generation, and age.

Cultural Individualism versus Collectivism

Changes in attitudes, values, and personality traits over time are rooted in cultural change (Twenge, 2014). Cultures and individuals mutually influence and constitute each other (Markus & Kitayama, 2010). The general idea that cultural change influences individuals has broad theoretical (e.g., Fukuyama, 1999; Mannheim, 1952; Myers, 2000; Putnam, 2000) and empirical support (e.g., Konrath, O’Brien, & Hsing, 2011; Malahy, Rubinlicht, & Kaiser, 2009; Reynolds, Stewart, MacDonald, & Sischo, 2006; Twenge, Campbell, & Gentile, 2012).

Much of the work on cultural change has focused on increases in individualism (e.g., Fukuyama, 1999; Myers, 2000; Twenge, 2014). This is similar to ideas in sociology suggesting that modernity leads to less religiosity and more secularism (Norris & Inglehart, 2004; Ruiter & van Tubergen, 2009) and those in political science suggesting that societies have increased in personal empowerment and emancipation (Welzel, 2013). Individualism is a cultural system that favors the needs or desires of the individual over those of the group. As a result, more individualism should mean a relaxation of rules around marriage and sexuality. At base, marriage represents society’s official recognition of a sexual relationship. Cultural individualism instead promotes the idea that social rules and societal recognition are less important (Fukuyama, 1999), which may encourage more acceptance of sexual behavior outside of marriage. Overall, individualism is associated with increased acceptance of premarital sex and sexually permissive behavior (Ven-hwei, So, & Guoliang, 2010). A systematic review of behavioral research from 1985 to 2007 found that stronger connectedness to friends, family, and communities, usually linked to collectivism, is associated with reduced sexual risk behavior (Markham et al., 2010). Further, the association between pornography consumption and sexually permissive attitudes is strongest among those who are more sexually liberal, an attitudinal disposition characterized by sexual individuality (Wright, 2013). As such, individualism may heighten attitudinal and behavioral responses to social and sexual experiences. A collectivistic cultural mindset may also explain the significantly lower rates of sexual risk behavior in Asian cultures and Asian-American samples (Tosh & Simmons, 2007).

Previous research found that American culture has become increasingly individualistic. For example, cultural products such as song lyrics and written language are now more likely to use first person singular (I, me, mine) and second person (you, your) pronouns, and less likely to use first person plural pronouns (we, us) (DeWall, Pond, Campbell, & Twenge, 2011; Twenge, Campbell, & Gentile, 2013). Compared to books in the past, recent American books used fewer words describing moral character, including words relevant to sexual behaviors such as virtue, honor, modesty, and purity (Kesebir & Kesebir, 2012). Word pairs showed decreases in collectivism and increases in individualism relevant for sexual behavior; for example, use of the word “obliged” decreased, and use of the word “choose” increased (Greenfield, 2013). Adolescents’ religious affiliation, religious service attendance, and religiosity declined between the 1970s and the 2010s (Twenge, Exline, Grubbs, Sastry, & Campbell, in press). These results are consistent with the idea that American culture has become more focused on the individual and his/her choices and less focused on following social rules, and thus should demonstrate increased sexual permissiveness.

The Importance of Sexual Attitudes and Behavior

Sexual attitudes and behaviors are critical factors due to their role in a variety of outcomes, including sexually transmitted diseases (Scott-Sheldon, Medina, Warren, Johnson, & Carey, 2011), abuse and assault prevention (Santos-Iglesias, Sierra, Vallejo-Medina, 2013), mental health (Bersamin et al., 2014; Vrangalova, 2014), and relationship outcomes (Greene & Faulkner, 2005; Hendrick, Hendrick, & Reich, 2006; Raiford, Seth, & DiClemente, 2013). Further, women experience more shame and guilt associated with premarital sexual behavior than men (Cuffee, Hallfors, & Waller, 2007), which may help explain gender differences in emotional responses to casual sex (Fielder & Carey, 2010; Townsend & Wasserman, 2011) and sexual debut (Sprecher, 2014). Similarly, sexual attitudes, such as sexual conservatism, may explain cultural differences in sexual guilt and sexual desire (Woo, Brotto, & Gorzalka, 2011) and may also partially account for gender and racial and ethnic differences in sexual behavior, including sexual risk behavior (Cuffee et al., 2007; Meston & Ahrold, 2010).

Although attitudes toward premarital sex and same-sex sexual activity are different concepts with varying origins, both impact mental and physical health. For example, internalized negative attitudes among sexual minorities have been consistently identified as predictors of negative mental health outcomes (Hatzenbuehler, 2009; Meyer, 2013) and sexual risk behavior and substance use among gay and bisexual men (Hatzenbuehler, Corbin, & Fromme, 2011; Hatzenbuehler, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Erikson, 2008; Newcomb & Mustanski, 2011).

Understanding the interplay between sexual attitudes and behavior also provides insight into the mechanisms of attitude and behavioral changes over time, highlighting the importance of examining both simultaneously. Sexual attitudes are strong predictors of sexual behavior, including sexual risk behavior (Cuffee et al., 2007; Lam & Lefkowitz, 2013), engagement in casual sex (Katz & Schneider, 2013), and number of sexual partners (Townsend & Wasserman, 2011). Personal and perceived peer norms about refraining from sexual behavior may also serve as protective factors against the early initiation of sexual activity (Santelli et al., 2004). On the other hand, engaging in sexual behavior may influence sexual attitudes as people modify their attitudes to become more consistent with their own behavior and experiences. For example, Huebner, Neilands, Rebchook, and Kegeles (2011) found that, longitudinally, engaging in sexual risk behavior predicted attitudes about condom use, but attitudes did not longitudinally predict behavior.

Previous Research and the Current Study

Previous studies found that attitudes toward premarital sex shifted substantially between the 1960s and 1970s but (in some samples) stayed fairly steady during the 1980s and 1990s (Harding & Jencks, 2003; Smith, 1990; Treas, 2002; Wells & Twenge, 2005). Attitudes toward same-sex sexual activity were steady until the 1990s and then became significantly more accepting (Harding & Jencks, 2003; Percell, Green, & Gurevich, 2001; Smith, 1990; Treas, 2002). However, it is uncertain how these attitudes have changed in the years since 1999, the most recent year examined in these previous studies. Because attitudes toward premarital sex leveled off after the 1980s, attitudes may be no different in the 2010s than they were 30 years ago.

Only a few studies have examined trends in sexual behavior in the United States. A meta-analysis found that sexual activity among adolescents increased between the 1950s and the 1990s, especially among girls (Wells & Twenge, 2005). Examining a small subset of the GSS (18- to 25-year-olds who had attended college), Monto and Carey (2014) concluded that claims of a new “hookup culture” were largely unfounded, with no changes in the number of sexual partners since age 18. Petersen and Hyde (2010) meta-analytically examined gender differences in sexual attitudes and behavior and found a decreased gender difference over time in several sexual behaviors and attitudes, including engagement in sexual intercourse, number of sexual partners, and engagement in and attitudes about premarital sex. In large national datasets, the decreased gender difference was driven by changes in boys’ attitudes and behavior. An analysis of Youth Risk Behavior Survey data from 1991 to 2009 indicated that the proportion of high school students reporting multiple partners decreased during this period (Eaton et al., 2011). In contrast, among college students enrolled in a human sexuality class at a Midwestern university, the 2005–2012 students were more sexually permissive than the 1995–1999 students (Sprecher, Treger, & Sakaluk, 2013). Thus, the current research literature provides contradictory evidence on whether sexual attitudes and behaviors have grown more or less permissive in recent years.

In addition, none of these studies employed the new mixed effects model techniques that can separate the effects of time period, generation, and age (Yang, 2008). It is also unknown whether all demographic groups or only some show effects (for example, do trends differ for Whites and Blacks? Among the religious and non-religious?) Thus, the current research had three goals: (1) to determine trends in adult Americans’ sexual attitudes and behaviors through the 2010s, (2) to analyze whether these trends were due to time period, generation, or age; and (3) to examine whether these trends were moderated by gender, race, education, U.S. region, or religious service attendance.

The rise in cultural individualism suggests that Americans should increasingly approve of sex outside of marriage and have more sexual partners in their lifetimes. Although previous research suggested that the trend toward more sexually permissive attitudes and behavior leveled off during the 1980s and 1990s, we hypothesize that the continued movement toward individualism and away from traditional social rules during the 2000s and 2010s will result in more permissive sexual attitudes and behaviors.

Method

Participants

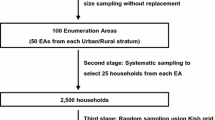

The GSS is a nationally representative sample of Americans over 18, collected in most years between 1972 and 2012 (N = 56,859; for the questions in the current analysis, N ranged from 21,702 to 33,380). The GSS data and codebooks are available online (Smith, Hout, & Marsden, 2013). As suggested by the GSS administrators, we weighted the descriptive statistics by the variable WTSSALL to make the sample nationally representative of individuals rather than households and to correct for other sampling biases. Also as suggested by the administrators, we excluded the Black oversamples collected in 1982 and 1987.

Measures

Single items on Sexual Attitudes and Behavior

From the beginning of the survey in 1972, the GSS asked four items about attitudes toward non-marital sex. The section begins “There’s been a lot of discussion about the way morals and attitudes about sex are changing in this country.” It then asks: (1) “Do you think it is wrong or not wrong if a man and a woman have sexual relations before marriage?” (2) “What if they are in their early teens, say 14 to 16 years old?”, (3) “What about a married person having sexual relations with someone other than his or her husband or wife,” and (4) “And what about sexual relations between two adults of the same sex?” Response choices, coded 1–4, are: “always wrong,” “almost always wrong,” “wrong only sometimes,” and “not wrong at all.”

Beginning in 1988, GSS asked several items on sexual behavior. The first question in the section asked: “How many sex partners have you had in the last 12 months?” with response choices ranging from zero (0) to more than 100 partners (8). We excluded the few (less than 3 % total) who responded “don’t know” or with vague responses such as “many, lots” or “more than one” (without giving an exact number). The next question asked, “Was one of the partners your husband or wife or regular sex partner?” with choices of “yes” and “no.” The next questions were asked only of those who had a partner other than a regular one in the last year: “If you had other partners, please indicate all categories that apply to them: close personal friend; neighbor, co-worker, or long-term acquaintance; casual date or pick-up; paid sex; other.” Response choices were “yes” or “no.”

Two questions asked about sexual partners since age 18: “Now thinking about the time since your 18th birthday (including the past 12 months) how many female partners have you had sex with?” and “Now thinking about the time since your 18th birthday (including the past 12 months) how many male partners have you had sex with?” We added these two items together to obtain total number of sexual partners since age 18. As distributions for sexual partners are heavily skewed with long right-hand tails (Schroder, Carey, & Vanable, 2003), we also recoded this item using the 0–8 scale employed for the two items on sexual partners in the last year. Another item asked, “Now think about the past five years and including the past 12 months, how many sex partners have you had in that five year period?” using the 0–8 scale. The last two relevant items were: “Thinking about the time since your 18th birthday, have you ever had sex with a person you paid or who paid you for sex?” (with choices of “yes” and “no;” we excluded “don’t know” responses) and “Have you ever had sex with someone other than your husband or wife while you were married?” (with choices of “yes” and “no;” we excluded those who answered “never married.”)

Composite Variable of Attitudes Toward Non-marital Sexuality

We performed a principal components analysis to determine whether the four sexual attitude variables could be combined into a composite variable of attitudes toward non-marital sexuality. We included only those individuals with 50 % or more of the items completed (at least 2 of the 4; almost all missing data were due to the GSS design of asking some questions, including these, of a randomly selected two-thirds of the sample. Refusal to answer and “don’t know” responses were rare, around 2 %). Parallel analysis (Horn, 1965) on the four attitude variables indicated that only a one component solution had an eigenvalue better than chance levels. Moreover, all variables loaded onto a single principal component explaining 51 % of the variance with component loadings ranging from .65 to .77. Therefore, all variables were standardized (z-scored) and a composite variable was formed (N = 15,546, M = 0.00, SD = 0.83, α = .85). This composite variable was subsequently standardized for all analyses.

Possible Moderators

The GSS also included demographic variables, making it possible to determine if changes in sexual attitudes and behavior differed by group. We analyzed moderation by gender (men vs. women), race (White vs. Black, the only racial groups measured in all years of the survey), education level (high school graduate and below vs. attended some college and above), religious service attendance (once a month or more vs. less), and U.S. region (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West).

Procedure

As initial steps, we report descriptive statistics, inferential statistics, effect sizes, and p values based on t tests for individual items and the composite for sexual attitudes in Table 1 and for the individual sexual behavior items in Table 2. Data collected over time can be analyzed in many ways, including grouping by 20-year generation blocks, by decades, or by individual year. We felt that separating the data into 5-year intervals provided the best compromise between specificity and breadth. We report the effect sizes (d, or difference in terms of SDs) comparing the first group of years to the last, but also provide the means and SDs for the 5-year intervals between these endpoints, so fluctuations at other times are apparent, and provide figures with some year-by-year results.

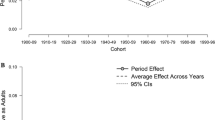

To better separate the effects of time period, generation/cohort, and age, we performed age, period, cohort (APC) analyses on the sexual attitudes composite and on two variables capturing the total number of sexual partners (on the 0–8 scale, and untransformed). We focused on number of sexual partners as we felt that this came closest to capturing sexually permissive behavior. Sexual partners in the last year captures only a short amount of time, and the other variables (extramarital sex, sex with a casual date or pickup, etc.) were asked only of the minority of the sample who had sex with someone other than a regular partner, creating n’s too small for APC analysis. In addition, the use of number of sexual partners connects this research with the literature on sociosexual orientation (Penke, 2011; Simpson & Gangestad, 1991).

Following the recommendations of Yang and Land (2013), we estimated mixed effects models allowing intercepts to vary across time periods (years) and generations (cohorts). Thus, effectively, an intercept (mean attitudes toward sexuality) score was calculated (using empirical Bayes) for each cohort and each survey year. In addition, a fixed intercept (grand mean) is estimated along with a fixed linear effect of age. This model has three variance components: One for variability in intercepts due to cohorts (τu0), one for variability in intercepts due to period (τv0), and a residual term containing unmodeled variance within cohorts and periods. Variance in the intercepts across time periods and cohorts indicates period and cohort differences, respectively. Effectively, this allows us to estimate the mean attitude towards sexuality (or mean number of sexual partners) for each period and cohort that are independent of each other and age. Weighting could not be used for the mixed-effects analyses because proper probability weighting for variance component estimation requires taking into account pairwise selection probabilities, which is not possible with current statistical software.

To focus on the general trends, we grouped birth cohorts by decade with the exception of the first cohort (1883–1889) and the last cohort (1990–1994) as they did not make complete decades by themselves. In describing the trends in the text, we will sometimes employ common labels for the generations such as the G.I. or “Greatest” generation (born 1900-1924), Silent (1925–1945), Boomers (1946–1964; some argue 1943–1960), GenX (1965–1981 or 1961–1981), and Millennials (1982–1999) (for reviews, see Strauss & Howe, 1991; Twenge, 2014). These birth year cutoffs are arbitrary and are not necessarily justified by empirical evidence, but are useful labels for those born in certain eras.

Results

Between the 1970s and the 2010s, American adults became more accepting of premarital sex, adolescent sex, and same-sex sexual activity, but less accepting of extramarital sex (see Table 1; Fig. 1; we report means, effect sizes, and significance testing in the tables and report percentage agreement in the text). After leveling off in the 1990s, acceptance of premarital sex continued to rise in the 2000s and 2010s. In the early 1970s, 29 % of Americans (35 % of men and 23 % of women) believed that premarital sex was “not wrong at all.” This rose to around 42 % in the 1980s and stayed there through the 1990s, rising to 49 % in the 2000s and to 55 % in the 2010s (59 % of men, 52 % of women). The majority of Americans were accepting of premarital sex by 2008. Among 18- to 29-year-olds, 47 % of Boomers in the early 1970s believed premarital sex was “not wrong at all,” compared to 50 % of GenX’ers in the early 1990s and 62 % of Millennials in the 2010s.

Acceptance of sexual activity among adolescents rose slightly but significantly (in t tests comparing means; see Table 1), with approval rising from 4 % in 2006 (5.6 % of men, 3.0 % of women) to 6 % in 2012 (6.4 % of men, 5.7 % of women). Although remaining at a low level, acceptance of extramarital sex (sex between a married person and someone other than his/her spouse) declined significantly from 4 % in 1973 (5.9 % for men, 1.9 % for women) to 1 % in 2012 (2 % for men, .6 % for women).

Acceptance of sexual activity among two adults of the same sex increased the most, especially after the 1990s. Acceptance hovered between 11 % and 16 % (with few differences among men and women) until 1993, when it shot up to 22 % (21 % for men, 23 % for women). It increased steadily after that, reaching 44 % in 2012 (35 % for men, 51 % for women). Thus, women are more accepting of sex between two adults of the same sex in the 2010s, even though they remain less accepting of premarital sex, sex among teens, and extramarital sex. Among 18- to 29-year-olds, 21 % of Boomers in the early 1970s believed same-sex sexual activity was “not wrong at all,” compared to 26 % of GenX’ers in the early 1990s and 56 % of Millennials in the 2010s.

Sexual behavior changed as well (see Table 2). Total number of sexual partners since age 18 increased from 7.17 in the late 1980s (11.42 for men, 3.54 for women) to 11.22 in the 2010s (18.22 for men, 5.55 for women). Transformed to a 0–8 scale, total partners increased from 3.03 in the late 1980s (3.87 for men, 2.31 for women) to 3.55 in the 2010s (4.18 for men, 3.03 for women). Among 18- to 29-year-olds reporting non-partner sex, 35 % of GenX’ers in the late 1980s had sex with a casual date or pickup (44 % of men, 19 % of women), compared to 45 % of Millennials in the 2010s (55 % of men, 31 % of women).

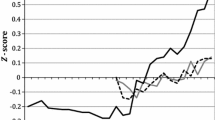

Separating Time Period, Generation, and Age

Next, we turned to the mixed-effects analyses to determine whether the changes were due to time period, generation/cohort, and/or age. Age produced a small but statistically significant effect (b = −.008 [95 % confidence interval −.010 to −.006], SE = .001), with older individuals expressing slightly less favorable attitudes towards non-marital sex. Time period (SD = .06 [.04, .10]) and generation/cohort (SD = .23 [.12, .34]) were both significant influences, suggesting both may play a role in the changes in attitudes. However, generation explained nearly four times more of the variance than time period. The random effects of time period and generation, which statistically control for each other and age, are plotted in Fig. 2. Acceptance of non-marital sex declined slightly between the early 1970s and the early 1990s (d = −.09 between 1974 and 1990), with attitudes returning to 1970s levels by 1994. Attitudes were fairly steady between 1994 and 2004 and then became more accepting between 2004 and 2012 (d = .15).

The generational trend was somewhat curvilinear, with the largest difference between those born in the 1900s and Boomers born in the 1940s and 1950s (d = .52), a slight decline between the 1950s-born Boomers and 1960s-born GenX’ers (d = −.09), and a rise in acceptance between GenX’ers born in the 1960s and Millennials born in the 1980s–1990s (d = .14). The generational difference between those born in the 1900s (the G.I. or “Greatest” generation) versus the 1980s–1990s (Millennials) was d = .58.

We conducted a similar analysis using total number of sexual partners on a 0–8 scale (with 0–4 = number of partners; 5 = 5–10; 6 = 11–20; 7 = 21–100 and 8 = 100 or more), as the dependent variable. Age exerted a small but statistically significant effect (b = .015, [.007, .025], SE = .004). The overwhelming majority of variation in number of sexual partners was generational (SD = 1.11 [.57, 1.68]), with much less variation in intercepts due to time period (SD = 0.10 [.00, .17]). Americans born in the 1900s reported one sexual partner on average, while those born in the 1950s and later reported slightly less than four on a 0–8 scale (see Fig. 3). Number of sexual partners rose steadily between G.I.’s born in the 1900s and 1960s-born GenX’ers, d = 1.29. Number of partners then declined slightly between the 1960s-born cohort and the Millennials born in the 1980s–1990s, d = − .21, returning to Boomer levels. However, Millennials reported considerably more sexual partners than those born in the 1900s, d = 1.07.

Analyses of the untransformed number of sexual partners revealed that generation accounted for considerably more variance in total number of sexual partners (SD = 4.01 [1.65, 6.26]) than time period (SD = 1.07 [0.00, 1.82]). Age produced a small, but statistically significant effect (b = .09, [.003, .187], SE = .04), suggesting that older individuals reported more sexual partners, with .09 additional partners per year of age. The generational effects were curvilinear, with the mean number of partners moving from 2.12 for those born in the 1910s to 11.68 for those born in the 1950s, and then declining to 8.26 for those born in the 1980s–1990s. Thus, Millennials report 6 more sexual partners than G.I.s, Boomers reported 9 more partners than G.I.s, and Millennials reported 3 fewer partners than Boomers. The median number of partners was 1 for those born in the 1910s–1920s, 2 for the 1930s cohort, 3 for the 1940s, 4 for the 1950s–1960s, and 3 for those born in the 1970s–1990s.

Moderators

We then examined whether these generational differences in attitudes and behavior (based on the APC coefficients) differed by gender, race, education level, U.S. region, and religious service attendance. Because of our large representative sample and the difficulties involved in identifying proper error terms of significance tests of random effects coefficients, we instead report effect sizes, considering any difference in effect sizes greater than d = .10 worth discussing (as this is half of Cohen’s (1988) guideline of d = .20 as a “small” effect).

The generational shift in attitudes toward non-marital sexuality (born 1900s vs. 1980s–1990s) was larger for men (d = .65) than for women (d = .16). Among those born in the 1900s, men’s attitudes were only slightly more sexually permissive (d = .12), but this gender gap widened among those born in the 1980s–1990s (d = .38). The generational shift was larger for Whites (d = .71) than Blacks (d = .02). Among those born in the 1900s, Blacks’ attitudes were more sexually permissive than Whites’ (d = .41), but among those born in the 1980s–1990s, Blacks’ attitudes were less permissive than Whites’ (d = −.28). The generational shift was larger among those who attended college (d = .42) than those who did not (d = .08); among those born in the 1900s, education level did not affect attitudes (d = −.02), but by the 1980s–1990s cohort those who attended college were more permissive (d = .32). The generational shift was moderated by U.S. region, with the largest shifts occurring in the West (d = .40), followed by the Northeast (d = .22), the Midwest (d = .20), and the South (d = .03). Religious service attendance did not moderate the generational effect on attitudes. As main effects, participants from the South and those who attended religious services once a month or more were less accepting of non-marital sex.

For sexual behavior (total number of sexual partners as an adult, 0–8 scale), the generational shift (1900s vs. 1960s) was larger for men (d = 1.35) than for women (d = 1.07), and considerably larger for Whites (d = 1.27) than Blacks (d = .10). Among those born in the 1900s, Blacks reported significantly more sexual partners than Whites (d = 1.08), but among those born in the 1960s, Whites reported more slightly more partners (d = −.09; among those born in the 1980s–1990s, Blacks reported slightly more, d = .09). The generational shift was larger for those who had not attended college (d = 1.32) compared to those who did (d = .27). Among those born in the 1900s, those who attended college reported more partners than those who did not (d = .82), but among those born in the 1960s, those who did not attend college reported more partners (d = −.19; among those born in the 1980s–1990s, those attending college reported slightly more, d = .08). By region, generational shifts were largest in the Northeast (d = 1.25), followed by the West (d = .72), the South (d = .70), and the Midwest (d = .63). Among those born in the 1900s, those living in the Northeast reported the fewest number of partners (d = −.55 compared to the other three regions), but by the 1980s–1990s cohort Northeasterners reported slightly more than those in other regions (d = .23). The generational shift was larger among those who did not attend religious services (d = 1.50) compared to those who did (d = .95). Among those born in the 1900s, attending religious services had little influence on number of sexual partners (d = .10), but among those born in the 1960s the difference widened (d = .46; for those born 1980s–1990s, d = .42). In most cases, d’s comparing cohorts were lower (by about .20) for the 1900s vs. 1980s–1990s comparisons than the 1900s vs. 1960s comparisons. As main effects, men reported more partners than women and those who attended religious services fewer partners than those who did not.

Discussion

Between the 1970s and the 2010s, Americans became more accepting of non-marital sex, with the exception of extramarital sex. After changing little in their attitudes during the 1980s and 1990s, Americans became more accepting of non-marital sex during the 2000s and 2010s. American adults in the 2010s (vs. the late 1980s) reported having sex with more partners and were more likely to have had sex with a casual date or pickup or an acquaintance in the last year. However, shifts in sexual attitudes and behaviors were nearly absent among Black Americans.

Mixed-effects models separating time period, generation, and age showed that the trends were primarily due to generation. Once age and time period effects were removed, many generational differences were considerable, exceeding d = .50 for attitudes and d = 1.00 for behavior; Cohen (1988) provided general guidelines of d = .20 as small, d = .50 medium, and d = .80 or over as large. Thus, contrary to the position that generational differences are non-existent or small (e.g., Trzesniewski & Donnellan, 2010), generations born later in the twentieth century (compared to those born earlier) held significantly more permissive attitudes toward non-marital sex and had sex with a greater number of partners.

Overall, the results suggest that rising cultural individualism has produced an increasing rejection of traditional social rules, including those against non-marital sex. Consistent with past research finding declines in religious orientation and increases in individualistic traits (e.g., Greenfield, 2013; Twenge et al., 2012, Twenge et al., in press; for a review, see Twenge, 2014), more Americans believe that sexuality need not be restricted by social conventions. Recent generations are also acting on this belief, reporting a significantly higher number of sexual partners as adults and more having casual sex than those born earlier in the twentieth century.

These trends may also be due to shifting norms around marriage. The median age at first marriage has risen markedly; it was 21 for women and 23 for men in 1970, and by 2010 was 27 for women and 29 for men. The marriage rate in the U.S. reached a 93-year low in 2014 (Bedard, 2014). With more Americans spending more of their young adulthood unmarried, they have more opportunities to engage in sex with more partners and less reason to disapprove of non-marital sex. Marriage is also increasingly disconnected from parenting: More than 40 % of babies were born to unmarried mothers in 2012, up from 5 % in 1960 (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2012).

The advent of HIV/AIDS in the 1980s may have influenced sexual attitudes and behaviors. Acceptance of non-marital sex dipped slightly during the late 1980s and early 1990s, during the time when public attention to AIDS was at its height (Swain, 2005). Later-born GenX’ers and Millennials—who reported fewer partners than those born in the 1950s and 1960s– became adults after HIV/AIDS was publicly recognized. However, participants in the 2010s (vs. the late 1980s) were more likely to report casual sex, suggesting that the threat of HIV infection has not affected the incidence of casual sex as much as the number of partners.

Mixed-effects (HLM) analyses separating time period, generation, and age demonstrated that the changes in sexual attitudes and behavior were primarily due to generation/cohort. With the exception of a slight dip among the 1960s-born cohort, sexual attitudes became steadily more accepting of non-marital sex over the generations, with attitudes the most permissive among Millennials born in the 1980s–1990s. Number of sexual partners rose steadily between those born in the 1900s and the 1960s, and then declined somewhat for those born in the 1980s–1990s. However, Millennials still reported more sexual partners than those born in the first half of the twentieth century. Thus Millennials have not ushered in a new era of sexual restrictiveness or a “sexual counter-revolution,” as some predicted (Howe & Strauss, 2000). In fact, Millennials hold the most permissive sexual attitudes of any generation, though they chose to have sex with fewer partners than GenX’ers did at the same age. The reduced number of partners among Millennials may reflect changes in dating and relationship patterns toward sexual relations (not necessarily involving intercourse) between “friends with benefits” while postponing the transition into more committed romantic relationships (Bogle, 2007; Wentland & Reissing, 2011). While these partnerships are casual in nature, they may be defined by regular contact between a limited number of individuals, perhaps reducing the overall number of partners.

The generational origin of the changes in sexual attitudes and behavior suggests that adolescents and young adults form their views around sexuality at earlier stages of development and do not alter them much beyond their formative developmental years (Rauer, Pettit, Lansford, Bates, & Dodge, 2013). They also suggest that parents and their adolescent and emerging adult children may have significant generation gaps in their views of non-marital sexuality, potentially leading to conflict. Future research should examine the role of the dominant cultural norms and values and parental influences exerted at these key stages of development.

The generational differences in sexual behavior exceeded d = .20 among both men and women, those who attended college versus not, among the religious and non-religious, and across regions. Generational shifts in sexual attitudes were smaller among some groups, such as Blacks, women, and those living in the South. As a general trend, differences based on group membership grew (for example, gender and education differences in sexual attitudes widened, and the religious and non-religious became more divergent in their number of sexual partners). Most notably, generational differences were nearly absent among Black Americans. Among generations born early in the twentieth century, Black Americans held more permissive attitudes and reported more sexual partners than Whites, but by the 1950s and 1960s cohorts Blacks were less permissive and reported fewer partners than Whites. Other research also indicates racial differences in temporal changes in sexual behavior. In the National Survey of Family Growth, the percentage of teenagers who reported premarital intercourse decreased 12 percentage points for Blacks but only 3 % points for Whites between 1979 and 1982 (Hofferth, Kahn, & Baldwin, 1987). The move towards more restrictive attitudes and behavior may reflect increased awareness of the disproportionate burden of sexually transmitted infections (including HIV) on the Black community. Due to the higher incidence of STIs, HIV, and adolescent pregnancy among Blacks (Beer, Oster, Mattson, & Skarbinski, 2014; Kost & Henshaw, 2014; Pflieger, Cook, Niccolai, & Connell, 2013), prevention and intervention efforts have targeted Blacks in an attempt to reduce sexual risk behavior, including the number of sexual partners. These trends may also be rooted in religious belief, as White adolescents declined in religiosity over the generations while Black adolescents did not (Twenge et al., in press). These disparities highlight the importance of examining subcultural norms and the negotiation of mainstream and subcultural norms and practices with public health realities.

Our results were in partial agreement and partial disagreement with Monto and Carey (2014), who stated they “found no evidence of substantial changes in sexual behavior that would indicate a new or pervasive pattern of non-relational sex among contemporary college students” (p. 605). Our analyses differed significantly in sampling (theirs examined only the 1988 and later GSS surveys and only 18- to 25-year-olds who had attended college, whereas ours included all GSS respondents starting in 1972). Nevertheless, we also found that number of sexual partners did not change much between those born in the 1950s and the 1980s–1990s. However, examining only these later cohorts misses the standard-deviation shift in number of sexual partners between those born in the 1900s and the 1950s. In addition, our analysis found a large generational shift in attitudes toward non-marital sex and a substantial increase (from 28 to 38 %) in those reporting sex with a casual date or hookup. Thus, we conclude, in contrast to Monto and Carey (2014), that meaningful generational changes in sexual attitudes and behavior have occurred.

Implications

These findings have implications for sexuality research, policy decisions and practices, and education and intervention development and implementation. First, researchers should use large over time datasets and more sophisticated statistical methods (such as HLM) to investigate behavioral and psychosexual responses to sweeping cultural changes in sexual and relationship attitudes. For example, research indicates generational differences in the associations between stigma, mental health, and sexual risk behavior among gay and bisexual men (Lelutiu-Weinberger et al., 2013), highlighting the need for research to further disentangle age and generational effects. Further, research indicates that conflicting messages about sexual behavior for women (i.e., to be both sexually desirable and behaviorally chaste) contribute to the use of scripted refusal strategies among women (wherein women learn to resist sex they do in fact want, and men learn to negotiate for sex) and may contribute to regrettable or unwanted sexual experiences (Beres, 2010; Muehlenhard & McCoy, 1991). As such, research should work to understand the complex interplay between sexual attitudes and behavior.

Next, generational changes in non-marital sexual attitudes and behaviors are particularly relevant as they influence policy decisions regarding sexual health and sexual education policies, such as decisions about emergency contraception and abortion availability and the debates around abstinence-only versus comprehensive sexual education (Sumner, Crichton, Theobald, Zulu, & Parkhurst, 2011). Perhaps one of the clearest examples of attitudinal changes impacting public policy is the recent federal passage of same-sex marriage, which follows the GSS years that saw the highest acceptance of same-sex sexual activity. This occurs at the regional level as well: Lax and Phillips (2009) found that voter opinion and policies were fairly congruent within states. Finally, findings indicating both generational and age effects highlight the importance of culturally competent interventions and target population involvement in intervention development and implementation. For example, youth involvement in the development of sexual education programs is likely critical to accurately represent and inform sexual attitudes and behaviors. Additionally, understanding the cultural context in which sexual values and behaviors developed is necessary in examining sexual attitudes and behaviors in different cohorts. In short, these findings indicate that variability in sexual attitudes and norms according to generation, age, gender, and race/ethnicity should be considered in the development and implementation of sexual education and sexual health intervention programs.

Limitations

A limitation of the current analysis was that the mixed-effects HLM coefficients are based on the available data. Those born in the 1920s and before were already in their 40s and older when GSS data collection began in the 1970s. Similarly, as of 2012 those born in the 1980s had not yet reached their late 30s or beyond, and those born in the 1950s had not yet reached their mid-60s. Although the analyses controlled for age, they cannot extrapolate unavailable data. Thus, it is possible that the apparent decline in acceptance of non-marital sex with age may be partially due to generation, as Boomers, GenX’ers, and Millennials have not yet reached older ages. If the age trajectory of sexual behavior and attitudes is different for these groups, then future analyses incorporating more comprehensive life-span data may find that generation explains even more of the increase in acceptance for non-marital sexuality than suggested here.

Same-sex marriage was legalized in Massachusetts in 2004, so some of the acceptance of same-sex sexual activity in the years since may be due to its recognition with legal marriage. However, at the time the 2012 data were collected, same sex marriage was not recognized at the U.S. federal level and was recognized by only 7 of the 50 states.

Conclusions

As individualism increased in the U.S., sexual attitudes and behavior became more permissive and less rule-bound. Attitudes toward non-marital sex changed the most dramatically in the last 15 years, reaching all-time highs of acceptance in the 2010s and among Millennials. Research should continue to examine these cultural trends to more clearly tie specific social and cultural events to these attitudinal changes. Americans’ sexual behaviors have changed as well, with one sexual partner the norm for those born early in the twentieth century and 3–4 partners more common for those born in the 1950s through the 1990s. Intriguingly, Millennials embraced more permissive attitudes toward non-marital sex but reported fewer sexual partners than GenX’ers born in the 1960s. Overall, this is a time of fascinating changes in the sexual landscape of the United States.

Notes

The term generation usually refers to people born in a certain span of years and birth cohort refers to those born in a certain year. We will primarily rely on generation as it is more commonly understood, but use birth cohort when referring to specific birth years. Similarly, we will primarily rely on the term time period as it is most commonly used in the literature on the topic (e.g., Schaie, 1965); here, it is interchangeable with survey year (the year participants completed the survey).

References

Bedard, P. (2014). Census: Marriage rate at 93-year low, even including same-sex couples. Washington Examiner. Retrieved September 22, 2014 from http://washingtonexaminer.com/census-marriage-rate-at-93-year-low-even-including-same-sex-couples/article/2553600.

Beer, L., Oster, A. M., Mattson, C. L., & Skarbinski, J. (2014). Disparities in HIV transmission risk among HIV-infected black and white men who have sex with men, United States, 2009. AIDS, 28, 105–114.

Beres, M. (2010). Sexual miscommunication? Untangling assumptions about sexual communication between casual sex partners. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 12, 1–14.

Bersamin, M. M., Zamboanga, B. L., Schwartz, S. J., Donnellan, M. B., Hudson, M., Weisskirch, R. S., … Caraway, S. J. (2014). Risky business: Is there an association between casual sex and mental health among emerging adults? Journal of Sex Research, 51, 43–51.

Bogle, K. A. (2007). The shift from dating to hooking up in college: What scholars have missed. Sociology Compass, 1, 775–788.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power in the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Coley, R. L., Lombardi, C. M., Lynch, A. D., Mahalik, J. R., & Sims, J. (2013). Sexual partner accumulation from adolescence through early adulthood: The role of family, peer, and school social norms. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53, 91–97.

Cuffee, J. J., Hallfors, D. D., & Waller, M. W. (2007). Racial and gender differences in adolescent sexual attitudes and longitudinal associations with coital debut. Journal of Adolescent Health, 41, 19–26.

DeWall, C. N., Pond, R. S., Campbell, W. K., & Twenge, J. M. (2011). Tuning into psychological change: Linguistic markers of psychological traits and emotions over time in popular U.S. song lyrics. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 5, 200–207.

Eaton, D. K., Lowry, R., Brener, N. D., Kann, L., Romero, L., & Wechsler, H. (2011). Trends in human immunodeficiency virus—and sexually transmitted disease–related risk behaviors among US high school students, 1991–2009. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 40, 427–433.

Fielder, R. L., & Carey, M. P. (2010). Predictors and consequences of sexual “hookups” among college students: A short-term prospective study. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39, 1105–1119.

Fukuyama, F. (1999). The great disruption: Human nature and the reconstitution of social order. New York: Free Press.

Greene, K., & Faulkner, S. L. (2005). Gender, belief in the sexual double standard, and sexual talk in heterosexual dating relationships. Sex Roles, 53, 239–251.

Greenfield, P. M. (2013). The changing psychology of culture from 1800 through 2000. Psychological Science, 24, 1722–1731.

Harding, D. J., & Jencks, C. (2003). Changing attitudes toward premarital sex: Cohort, period, and aging effects. Public Opinion Quarterly, 67, 211–226.

Hatzenbuehler, M. L. (2009). How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 707–730.

Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Corbin, W. R., & Fromme, K. (2011). Discrimination and alcohol-related problems among college students: A prospective examination of mediating effects. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 115, 213–220.

Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Erickson, S. J. (2008). Minority stress predictors of HIV risk behavior, substance use, and depressive symptoms: Results from a prospective study of bereaved gay men. Health Psychology, 27, 455–462.

Hendrick, C., Hendrick, S. S., & Reich, D. A. (2006). The brief sexual attitudes scale. Journal of Sex Research, 43, 76–86.

Hofferth, S. L., Kahn, J. R., & Baldwin, W. (1987). Premarital sexual activity among United States teenage women over the past 3 decades. Family Planning Perspectives, 19, 46–53.

Horn, J. (1965). A rationale and test for the number of factors in factor analysis. Psychometrika, 30, 179–185.

Howe, N., & Strauss, W. (1993). 13th gen: Abort, retry, ignore, fail?. New York: Vintage.

Howe, N., & Strauss, W. (2000). Millennials rising: The next great generation. New York: Random House.

Huebner, D. M., Neilands, T. B., Rebchook, G. M., & Kegeles, S. M. (2011). Sorting through chickens and eggs: A longitudinal examination of the associations between attitudes, norms, and sexual risk behavior. Health Psychology, 30, 110–118.

Katz, J. M., & Schneider, M. E. (2013). Casual hook up sex during the first year of college: Prospective associations with attitudes about sex and love relationships. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42, 1451–1462.

Kesebir, P., & Kesebir, S. (2012). The cultural salience of moral character and virtue declined in twentieth century America. Journal of Positive Psychology, 7, 471–480.

Konrath, S. H., O’Brien, E. H., & Hsing, C. (2011). Changes in dispositional empathy in American college students over time: A meta-analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15, 180–198.

Kost, K., & Henshaw, S. (2014). U.S. teenage pregnancies, births, and abortions, 2010: National and state trends by age, race and ethnicity. Guttmacher Institute. http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/USTPtrends10.pdf.

Lam, C., & Lefkowitz, E. (2013). Risky sexual behaviors in emerging adults: Longitudinal changes and within-person variations. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42, 523–532.

Lax, J. R., & Phillips, J. H. (2009). Gay rights in the States: Public opinion and policy responsiveness. American Political Science Review, 103, 367–386.

Lelutiu-Weinberger, C., Pachankis, J. E., Golub, S. A., Walker, J. J., Bamonte, A. J., & Parsons, J. T. (2013). Age cohort differences in the effects of gay-related stigma, anxiety and identification with the gay community on sexual risk and substance use. AIDS and Behavior, 17, 340–349.

Malahy, L. W., Rubinlicht, M. A., & Kaiser, C. R. (2009). Justifying inequality: A cross-temporal investigation of U.S. income disparities and just-world beliefs from 1973 to 2006. Social Justice Research, 22, 369–383.

Mannheim, K. (1952). The problem of generations. In K. Mannheim (Ed.), Essays on the sociology of knowledge. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. (Original work published 1928)

Markham, C. M., Lormand, D., Gloppen, K. M., Peskin, M. F., Flores, B., Low, B., & House, L. D. (2010). Connectedness as a predictor of sexual and reproductive health outcomes for youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 46, S23–S41.

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (2010). Cultures and selves: A cycle of mutual constitution. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5, 420–430.

Meston, C. M., & Ahrold, T. (2010). Ethnic, gender, and acculturation influences on sexual behaviors. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39, 179–189.

Meyer, I. H. (2013). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 1, 3–26.

Monto, M. A., & Carey, A. G. (2014). A new standard of sexual behavior? Are claims associated with the ‘hookup culture’ supported by general social survey data? Journal of Sex Research, 51, 605–615.

Muehlenhard, C. L., & McCoy, M. L. (1991). Double standard/double bind: The sexual double standard and women’s communication about sex. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 15, 447–461.

Myers, D. G. (2000). The American paradox: Spiritual hunger in an age of plenty. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Newcomb, M. E., & Mustanski, B. (2011). Moderators of the relationship between internalized homophobia and risky sexual behavior in men who have sex with men: A meta-analysis. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40, 189–199.

Norris, P., & Inglehart, R. (2004). Sacred and secular: Religion and politics worldwide. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Penke, L. (2011). Revised sociosexual orientation inventory. In T. D. Fisher, C. M. Davis, W. L. Yarber, & S. L. Davis (Eds.), Handbook of sexuality-related measures (3rd ed., pp. 622–625). New York: Routledge.

Percell, C. H., Green, A., & Gurevich, L. (2001). Civil society, economic distress, and social tolerance. Sociological Forum, 16, 203–230.

Petersen, J. L., & Hyde, J. S. (2010). A meta-analytic review of research on gender differences in sexuality, 1993–2007. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 21–38.

Pflieger, J. C., Cook, E. C., Niccolai, L. M., & Connell, C. M. (2013). Racial/ethnic differences in patterns of sexual risk behavior and rates of sexually transmitted infections among female young adults. American Journal of Public Health, 103, 903–909.

Putnam, R. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Rauer, A. J., Pettit, G. S., Lansford, J. E., Bates, J. E., & Dodge, K. A. (2013). Romantic relationship patterns in young adulthood and their developmental antecedents. Developmental Psychology, 49, 2159–2171.

Reynolds, J., Stewart, M., MacDonald, R., & Sischo, L. (2006). Have adolescents become too ambitious? High school seniors’ educational and occupational plans, 1976 to 2000. Social Problems, 53, 186–206.

Ruiter, S., & van Tubergen, F. (2009). Religious attendance in cross-national perspective: A multilevel analysis of 60 countries. American Journal of Sociology, 115, 863–895.

Santelli, J. S., Kaiser, J., Hirsch, L., Radosh, A., Simkin, L., & Middlestadt, S. (2004). Initiation of sexual intercourse among middle school adolescents: The influence of psychosocial factors. Journal of Adolescent Health, 34, 200–208.

Santos-Iglesias, P., Sierra, J. C., & Vallejo-Medina, P. (2013). Predictors of sexual assertiveness: The role of sexual desire, arousal, attitudes, and partner abuse. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42, 1043–1052.

Schaie, K. W. (1965). A general model for the study of developmental problems. Psychological Bulletin, 64, 92–107.

Schroder, K. E., Carey, M. P., & Vanable, P. A. (2003). Methodological challenges in research on sexual risk behavior: I. Item content, scaling, and data analytical options. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 26, 76–103.

Scott-Sheldon, L. A., Huedo-Medina, T. B., Warren, M. R., Johnson, B. T., & Carey, M. P. (2011). Efficacy of behavioral interventions to increase condom use and reduce sexually transmitted infections: A meta-analysis, 1991 to 2010. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, 58, 489–498.

Simpson, J. A., & Gangestad, S. W. (1991). Individual differences in sociosexuality: Evidence for convergent and discriminant validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 870–883.

Singh, B. K. (1980). Trends in attitudes toward premarital sexual relations. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 42, 387–393.

Smith, T. W. (1990). The polls—A report on the sexual revolution. Public Opinion Quarterly, 54, 415–435.

Smith, T. W., Hout, M., & Marsden, P. V. (2013). General Social Survey, 1972–2012 [Cumulative File]. ICPSR34802-v1. Storrs, CT: Roper Center for Public Opinion Research, University of Connecticut/Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributors], 2013-09-11. http://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR34802.v1.

Sprecher, S. (2014). Evidence of change in men’s versus women’s emotional reactions to first sexual intercourse: A 23-year study in a human sexuality course at a Midwestern university. Journal of Sex Research, 51, 466–472.

Sprecher, S., Treger, S., & Sakaluk, J. K. (2013). Premarital sexual standards and sociosexuality: Gender, ethnicity, and cohort differences. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42, 1395–1405.

Stepp, L. S. (2007). Unhooked: How young women pursue sex, delay love, and lose at both. New York: Riverhead.

Strauss, W., & Howe, N. (1991). Generations: The history of America’s future, 1584 to 2069. New York: Morrow.

Sumner, A., Crichton, J., Theobald, S., Zulu, E., & Parkhurst, J. (2011). What shapes research impact on policy? Understanding research uptake in sexual and reproductive health policy processes in resource poor contexts. Health Research Policy and Systems, 9, S3. doi:10.1186/1478-4505-9-S1-S3.

Swain, K. A. (2005). Approaching the quarter-century mark: AIDS coverage and research decline as infection spreads. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 22, 258–262.

Tosh, A. K., & Simmons, P. S. (2007). Sexual activity and other risk-taking behaviors among Asian-American adolescents. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, 20, 29–34.

Townsend, J. M., & Wasserman, T. H. (2011). Sexual hookups among college students: Sex differences in emotional reactions. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40, 1173–1181.

Treas, J. (2002). How cohorts, education, and ideology shaped a new sexual revolution on attitudes toward non-marital sex, 1972–1998. Sociological Perspectives, 45, 267–283.

Trzesniewski, K. H., & Donnellan, M. B. (2010). Rethinking “Generation Me”: A study of cohort effects from 1976–2006. Perspectives in Psychological Science, 5, 58–75.

Twenge, J. M. (2014). Generation Me: Why today’s young Americans are more confident, assertive, entitled—And more miserable than ever before (2nd ed.). New York: Atria Books.

Twenge, J. M., Campbell, W. K., & Gentile, B. (2012). Generational increases in agentic self-evaluations among American college students, 1966–2009. Self and Identity, 11, 409–427.

Twenge, J. M., Campbell, W. K., & Gentile, B. (2013). Changes in pronoun use in American books and the rise of individualism, 1960-2008. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 44, 406–415.

Twenge, J. M., Exline, J. J., Grubbs, J. B., Sastry, R., & Campbell, W. K. (in press). Generational and time period differences in American adolescents’ religious orientation, 1966–2014. PLoS One.

U.S. Bureau of the Census. (2012). Statistical abstract of the United States. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Ven-hwei, L., So, C. Y. K., & Guoliang, Z. (2010). The influence of individualism and collectivism on Internet pornography exposure, sexual attitudes, and sexual behavior among college students. Chinese Journal of Communication, 3, 10–27.

Vrangalova, Z. (2014). Does casual sex harm college students’ well-being? A longitudinal investigation of the role of motivation. Archives of Sexual Behavior. doi:10.1007/s10508-013-0255-1.

Walsh, R. (1989). Premarital sex among teenagers and young adults. In K. McKinney & S. Sprecher (Eds.), Human sexuality: The societal and interpersonal context (pp. 162–186). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Wells, B. E., & Twenge, J. M. (2005). Changes in young people’s sexual behavior and attitudes, 1943–1999: A cross-temporal meta-analysis. Review of General Psychology, 9, 249–261.

Welzel, C. (2013). Freedom rising: Human empowerment and the quest for emancipation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Wentland, J. J., & Reissing, E. D. (2011). Taking casual sex not too casually: Exploring definitions of casual sexual relationships. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 20, 75–91.

Woo, J. S., Brotto, L. A., & Gorzalka, B. B. (2011). The role of sex guilt in the relationship between culture and women’s sexual desire. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40, 385–394.

Wright, P. J. (2013). A three-wave longitudinal analysis of preexisting beliefs, exposure to pornography, and attitude change. Communication Reports, 26, 13–25.

Yang, Y. (2008). Social inequalities in happiness in the United States, 1972 to 2004: An age-period-cohort analysis. American Sociological Review, 73, 204–226.

Yang, Y., & Land, K. C. (2013). Age-period-cohort analysis: New models, methods, and empirical applications. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Twenge, J.M., Sherman, R.A. & Wells, B.E. Changes in American Adults’ Sexual Behavior and Attitudes, 1972–2012. Arch Sex Behav 44, 2273–2285 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0540-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0540-2