Abstract

This study examined longitudinal changes in condom use inconsistency and sexual encounters involving alcohol use and the within-person associations of these two risky sexual behaviors with other personal and contextual factors. Data were drawn from a sample of college students who completed surveys on four occasions across 3 years and included 317 participants (48 % male; 32 % African American, 28 % Latino American, and 40 % European American) who reported recent penetrative sexual activities on at least one of the occasions. Multilevel models revealed that, although condom use inconsistency increased and then leveled off over time, sexual encounters involving alcohol use showed a linear increase. Moreover, at times when students held more negative attitudes toward condoms than usual, they used condoms less consistently than usual; at times when students felt more anxious about HIV/AIDS than usual, they had more sexual encounters involving alcohol use than usual; and at times when students were involved in a serious relationship, they used condoms less consistently and had fewer sexual encounters involving alcohol use than usual. Findings demonstrate the utility of a developmental perspective in understanding sexual behaviors, the importance of examining the unique correlates of different risky sexual behaviors, and the distinctiveness between within-person versus between-person associations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Emerging adults in the United States account for a disproportionate number of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and unintended pregnancies. National estimates indicate that about half of all individuals contract a STI by age 24 (Cates, Herndon, Schulz, & Darroch, 2004) and most women who have abortions are in their 20s (Jones, Darroch, & Henshaw, 2002). Given the long-term implications of STIs and unintended pregnancies for physical health and psychological well-being, it is crucial to understand how risky sexual behaviors develop across emerging adulthood and how these behaviors are linked to other personal and contextual factors. Most prior studies on this topic, however, have been cross-sectional and are limited in their ability to capture longitudinal changes and within-person variations. Using multiple-wave, longitudinal data from college students, this study examined longitudinal changes in condom use inconsistency and sexual encounters involving alcohol use and the within-person associations of these two risky sexual behaviors with hedonistic outcome expectancies of condom use, anxiety about HIV/AIDS, and romantic involvement.

Longitudinal Changes

Arnett (2000) argued that the time between the late teens and the mid-20s constitutes a distinct developmental period in industrialized societies. During this time, individuals are expected to explore their identities and to defer decisions with long-term ramifications. Experimentation with risky behaviors may be part of identity exploration, because many emerging adults feel a sense of urgency to gain a wide range of experiences before they commit to the enduring responsibilities that are normative in adulthood (Ravert, 2009; Schulenberg & Maggs, 2002). About 70 % of high school completers enroll in college immediately after high school graduation (National Center for Education Statistics, 2010). College-attending emerging adults often enjoy more freedom to try different lifestyles and make mistakes than do their non-college-attending counterparts. College also affords a peer-dominated environment in which parental monitoring is low, alcohol use is common, and different social events provide expanded opportunities to meet potential partners (Cooper, 2006; Pascarella & Terenzini, 2005). Thus, it is reasonable to expect that beginning college could result in an increase in risky behaviors. Leaving college, in contrast, puts into motion another set of transitions, including beginning employment, becoming financially independent, and establishing new living arrangements, which present fewer opportunities for risky behaviors and entail less freedom and more responsibilities (O’Malley, 2004). Therefore, risky behaviors are likely to level off or even decline when emerging adults take on adult roles.

Because emerging adults have the highest rates of STIs (Cates et al., 2004) and unintended pregnancies (Jones et al., 2002) compared to any other age groups, it is important to understand how risky sexual behaviors—sexual behaviors that lead to higher likelihoods of these negative consequences (Kotchick, Shaffer, Forehand, & Miller, 2001)—develop during this period. We focused on inconsistent condom use, given that condoms remain the most commonly used method for safer sex among emerging adults (DiClemente, Salazar, Crosby, & Rosenthal, 2005) and that sole reliance on hormonal birth control in sequential, short-term monogamous or concurrent relationships contributes to the spread of STIs (Kretzschmar, 2000). We focused on sexual encounters involving alcohol use, given that the years of emerging adulthood are characterized by significant increases in alcohol use (O’Malley, 2004; Schulenberg & Maggs, 2002) and that alcohol reduces inhibitions and may promote risky sexual behaviors, especially in casual encounters where the primary situational cues involve sexual pleasure and arousal (Cooper, 2006; George & Stoner, 2000).

A number of studies have examined changes in aggregated measures of risky sexual behaviors over time, and their results are consistent with the theory of emerging adulthood (Arnett, 2000). In general, risky sexual behaviors increase during adolescence, and level off (e.g., Fergus, Zimmerman, & Caldwell, 2007) or decline (e.g., Moilanen, Crockett, Raffaelli, & Jones, 2010) during emerging adulthood. Findings are more mixed on non-aggregated measures of risky sexual behaviors, such as inconsistent condom use and sexual encounters involving alcohol use. Although some studies indicated that individuals used condoms less consistently from adolescence through emerging adulthood (Bauermeister, Zimmerman, Xue, Gee, & Caldwell, 2009; Capaldi, Stoolmiller, Clark, & Owen, 2002; O’Donnell, O’Donnell, & Stueve, 2001), at least one study (Bailey, Haggerty, White, & Catalano, 2011) showed that, controlling for such background characteristics as gender and race/ethnicity, there were no significant changes in condom use inconsistency in the 2 years after high school graduation. Few studies have examined how sexual encounters involving alcohol use change over time, but alcohol use increases during the late teens, particularly for college students, and declines toward the mid-20s (Schulenberg & Maggs, 2002). Moreover, alcohol-related expectancies of sexual (Lundahl, Davis, Adesso, & Lukas, 1997) and general (Sher, Wood, Wood, & Raskin, 1996) activity enhancement decrease after age 20. Therefore, sexual encounters involving alcohol use may change in a quadratic pattern similar to what is seen in alcohol use.

Within-Person Variations

Because STIs and unintended pregnancies are largely preventable, it is important to understand how risky sexual behaviors are related to other personal and contextual factors. Cooper, Shapiro, and Powers (1998) argued that sexual behaviors may serve a range of psychosocial functions. Individuals may have sex to enhance self-pleasure (i.e., an enhancement motive), to promote intimacy with a partner (i.e., an intimacy motive), to cope with negative emotions (i.e., a coping motive), and to avoid social disapproval (i.e., an approval motive). Cooper et al. (1998) showed empirically that different risky sexual behaviors were linked to different psychosocial motives. The use of sex to cope with negative emotions, for example, was associated with having multiple sexual partners, but not using condoms inconsistently. To the extent that different personal (e.g., hedonistic outcome expectancies of condom use and anxiety about HIV/AIDS) and contextual (e.g., romantic involvement) factors reflect different sexual motives, condom use inconsistency and sexual encounters involving alcohol use should be linked to these factors in unique ways.

Decisions about condom use are often based on hedonistic and/or relationship considerations. Qualitative studies (Jadack, Fresia, Rompalo, & Zenilman, 1997; Nettleman, Brewer, & Ayoola, 2007) indicate that two primary reasons for not using condoms are that condoms reduce sexual pleasure (i.e., an enhancement motive) and that using condoms implies a lack of trust in the partner (i.e., an intimacy motive). Sheeran, Abraham, and Orbell (1999) meta-analyzed 121 quantitative studies, and found that attitudes toward condoms, including beliefs about whether using condoms would interfere with sexual sensation and would negatively affect a romantic relationship, constituted the most reliable predictor of actual condom use. More recent work continues to lead to similar conclusions by showing that individuals who hold more negative hedonistic outcome expectancies of condom use (e.g., Koniak-Griffin & Stein, 2006; O’Leary et al., 2005) and those who have greater trust in and commitment to their partners (e.g., Greene & Faulkner, 2005; Umphrey & Sherblom, 2007) use condoms less consistently.

There is evidence that sexual encounters involving alcohol use are linked to sex-related anxiety and romantic involvement. A meta-analysis has shown that greater concerns about contracting HIV/AIDS are associated with more risky sexual behaviors (Gerrard, Gibbons, & Bushman, 1996). Counter-intuitively, in the face of serious or irreversible threats to health (e.g., contracting HIV/AIDS), the typical reaction is to ignore or distort the threat rather than to engage in behavioral changes. One major motive for alcohol use is to serve an avoidant coping function (Cooper, 2006; O’Malley, 2004). Individuals with high anxiety about HIV/AIDS may use alcohol to divert attention or ease tension (Stoner, George, Peters, & Norris, 2007). Few studies have explored the influence of romantic involvement on sexual encounters involving alcohol use, but warm, affective relationships reduce risky behaviors in general (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996). Moreover, social events in college are often organized with the purpose of meeting new people, and many students report using alcohol strategically to make it easier to have sex (Cooper, 2006; Ham & Hope, 2003). Individuals who have been involved in an established relationship may be less likely to take part in these activities, because they do not need to look for new partners and they may want to preempt jealousy from their existing partners (i.e., an approval motive) by not drinking with acquaintances who are seeking romantic and sexual encounters (Guerrero, Spitzberg, & Yoshimura, 2004).

Previous investigations of correlates of risky sexual behaviors have mostly examined between-person variations. A focus on within-person variations extends this work by examining whether changes in risky sexual behaviors are linked to changes in other personal and contextual factors. By treating each individual as his or her own control, within-person associations exclude stable, third variables as alternative explanations and allow for stronger inferences (Curran & Bauer, 2011). To our knowledge, no studies have explored the time-varying covariates of sexual encounters involving alcohol use. Two studies (Bailey et al., 2011; Bauermeister et al., 2009) have examined the time-varying covariates of condom use inconsistency, but both of them have focused on contextual factors, such as college attendance and living arrangements, rather than personal factors. Bailey et al. (2011) showed that at times when individuals were involved in a romantic relationship, they used condoms less consistently than usual.

Control Variables

We controlled for gender, race/ethnicity, and participation in Greek organizations, given research indicating that risky sexual behaviors vary by gender, racial/ethnic groups (Lefkowitz, Gillen, & Vasilenko, 2010), and Greek affiliation (Cooper, 2006; Pascarella & Terenzini, 2005). We also controlled for parental education, because lower family socioeconomic status has been found to be linked to different risky sexual behaviors (Cates et al., 2004; Jones et al., 2002).

Study Goals and Hypotheses

In sum, this study examined longitudinal changes and within-person variations in condom use inconsistency and sexual encounters involving alcohol use. Hypotheses tested were:

Hypothesis 1

(a) Condom use inconsistency and (b) sexual encounters involving alcohol use would increase and then level off or decline over time.

Hypothesis 2

Condom use inconsistency would be (a) negatively associated with positive hedonistic outcome expectancies of condom use and (b) positively associated with romantic involvement.

Hypothesis 3

Sexual encounters involving alcohol use would be (a) positively associated with anxiety about HIV/AIDS and (b) negatively associated with romantic involvement.

Method

Participants

Based on information provided by the registrar’s office of a large, northeastern university in the United States, we contacted all African American and Latino American and a random sample (about 9 %) of European American first-year students who were aged 17–19 years. We oversampled African American and Latino American students, because these racial/ethnic groups are at higher risks of STIs (Cates et al., 2004) and unintended pregnancies (Jones et al., 2002). Of the initial 839 students contacted, 434 (52 %) agreed to participate. These students completed surveys in group sessions in the fall (Time 1) and spring (Time 2) of their first year, the fall of their second year (Time 3), and the fall of their fourth year (Time 4), and received $25–35 (depending on the wave of data collection) for compensation. Because the sexual scripts that direct heterosexual and homosexual sexual behaviors differ (Gagnon, 1990), we excluded 16 participants who identified their sexual orientation as homosexual, bisexual, or other at Time 1. The retention rate was 95 % at Time 2 (N = 399), 90 % at Time 3 (N = 376), and 78 % at Time 4 (N = 327). We only included participants who reported recent penetrative sexual activities on at least one of the measurement occasions (N = 317). At Times 1, 2, 3, and 4, sexual activity data were provided by 205, 206, 209, and 221 participants, respectively. At Time 1, the average age was 18.47 years (SD = .38). The sample was 48 % male, and 32 % African American, 28 % Latino American, and 40 % European American. The parents of most participants had graduated from high school (>90 % for both fathers and mothers), but beyond that parents’ educational levels were diverse, with some having vocational or technical diplomas (6 % for fathers and 8 % for mothers) and some having graduate or professional degrees (31 % for both fathers and mothers). This study was approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Outcome Variables

At Times 1 through 4, participants were given the definition of penetrative sex (“sex in which the penis penetrates the vagina or anus”), and instructed to report on their behaviors during penetrative sexual activities in the past 12 weeks. Risky sexual behaviors were measured using two items. Participants rated their condom use inconsistency (“In the past 12 weeks, how frequently did you use a condom when you had sex?”) and sexual encounters involving alcohol use (“In the past 12 weeks, how frequently did you consume alcohol before or during sexual encounters?”) on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = never, 1 = some of the time; 2 = most of the time; 3 = every time except once; 4 = every time). Participants who had not had penetrative sex during the past 12 weeks on a measurement occasion were coded as missing. Although single items were used, cross-time stability was evident, with auto-correlations averaging r = .41 for condom use inconsistency and r = .44 for sexual encounters involving alcohol use. For ease of interpretation, condom use inconsistency was reverse coded such that higher scores represented higher risks.

Predictor Variables

Hedonistic outcome expectancies of condom use were measured using the 5-item hedonistic expectancies subscale of the Outcome Expectancies of Condom Use Scale (Jemmott & Jemmott, 1992). At Times 1 through 4, participants rated such items as “Sex is natural when condoms are used” on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 2 = mildly disagree; 3 = neither disagree or agree; 4 = mildly agree; 5 = strongly agree). Hedonistic outcome expectancies were measured as the sum of the items, with higher scores representing more positive attitudes. Cronbach alphas across Times 1 through 4 averaged α = .79.

Anxiety about HIV/AIDS was measured using the 3-item anxiety about AIDS exposure subscale of the Multidimensional AIDS Anxiety Questionnaire (Snell & Finney, 1996). At Times 1 through 4, participants rated such items as “I sometimes worry that one of my past sexual partners may have had AIDS” on a 5-point Likert (1 = strongly disagree; 2 = mildly disagree; 3 = neutral; 4 = mildly agree; 5 = strongly agree). Anxiety about HIV/AIDS was measured as the sum of the items, with higher scores representing greater anxiety. Cronbach alphas across Times 1 through 4 averaged α = .81.

Romantic involvement was measured using one item. At Times 1 through 4, participants described their relationship status on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = I am not dating anyone right now; 1 = I am casually dating someone; 2 = I am in a relationship, but it is not very serious; 3 = I am in a serious and committed relationship; 4 = I am engaged, living with, and/or married to my partner). A binary variable was created to indicate whether participants were involved in a serious relationship (responses 0, 1, and 2 were coded as 0 = no; responses 3 and 4 were coded as 1 = yes) at each Time (see Table 1 for descriptive statistics for outcome and predictor variables).

Control Variables

Background characteristics, including gender and race/ethnicity, were measured at Time 1. Participation in Greek organizations was measured at Times 1 and 2, and a binary variable was created to indicate whether participants were members of a Greek organization in their first year. The educational levels of fathers and mothers at Time 1 were averaged, and used as a general index of family socioeconomic status in the models.

Analysis Plan

To examine longitudinal changes and within-person variations in condom use inconsistency and sexual encounters involving alcohol use, we used multilevel modeling as our analytic strategy. This strategy is appropriate when the data are nested and the residual errors are correlated (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). A further strength of multilevel modeling is that it accommodates certain types of missing data and produces unbiased estimates (Schafer & Graham, 2002). Missing values in our data were mainly caused by participants who dropped out of the study (attrition) or participants who had not had penetrative sex during the past 12 weeks on a measurement occasion (planned missingness). Because attrition was beyond our control and the resultant missing data pattern was not known, we employed a pattern-mixture approach (Hedeker & Gibbons, 1997) to test whether these missing data had an influence on our substantive conclusions (detailed later). Because planned missingness involved data that were not intended to be collected in the first place (i.e., risky sexual behaviors from participants who had not had sex), however, the missing data pattern was known to be random and have negligent impact on the estimation in multi-level models (Schafer & Graham, 2002).

We estimated a series of two-level models using the MIXED procedure in SAS Version 9.1. Preliminary analyses showed that, although other outcome and predictor variables generally followed a normal distribution, sexual encounters involving alcohol use were positively skewed (skewness ranged from 1.87 to 2.12). Therefore, square root transformations of sexual encounters involving alcohol use (skewness ranged from −0.10 to 0.85) were used in the analyses.Footnote 1 At Level 1 (within-person), we included time polynomials to describe longitudinal changes in risky sexual behaviors from Times 1 through 4. We used measurement occasions as the metric of time. Time was centered at Time 1, such that the intercepts estimated the sample means of risky sexual behaviors when participants first entered college. Times 2, 3, and 4 were coded as 4, 10, and 34, respectively, to indicate the approximate time intervals (in months) between the measurement occasions. To distinguish within-person from between-person variations, each time-varying covariate (i.e., hedonistic outcome expectancies of condom use, anxiety about HIV/AIDS, and romantic involvement) was indicated by two variables in the model. At Level 1, the covariate was indicated by a time-varying, group-mean centered (i.e., centered at each individual’s cross-time average) variable. At Level 2, the covariate was indicated by the time-invariant, grand-mean centered (i.e. centered at the overall sample mean) cross-time average. Because the cross-time average at Level 2 captured all the between-person variations, the time-varying version of the covariate at Level 1 was limited to explaining within-person variations beyond stable individual differences (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). Because romantic involvement was indicated by a binary variable at each Time, instead of the cross-time average, we included another binary variable at Level 2 to indicate whether participants were ever involved in a serious relationship across Times 1 through 4. Therefore, the between-person romantic involvement variable indicated a general tendency to be in a serious relationship, whereas the within-person romantic involvement variable indicated participants’ time-varying relationship status. At Level 2 (between-person), we included time-invariant characteristics, including participants’ gender, race/ethnicity, and participation in Greek organizations, their parents’ educational levels, and the cross-time averages of the time-varying covariates. The reference group (i.e., group coded as 0) for gender was men. Two binary variables were created to indicate African American and Latino American race/ethnicity, leaving European Americans as the reference group. The reference group for Greek affiliation was non-members. Parental education was centered at 4 (i.e., high school graduate).

We conducted the analyses in three steps. First, we examined the patterns of change of condom use inconsistency and sexual encounters involving alcohol use across Times 1 through 4. To identify the best error structure, we compared a series of nested models that differed only in the random effect of interest. We used deviance tests (instead of parameter estimates as in the case of fixed effect components) to determine the statistical significance of the random effect components (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). Because the difference between two nested models in their deviances (i.e., −2 log likelihood) was Chi-squared distributed, it indicated whether adding the random variance component significantly improved the fit of the model (i.e., constituted a better error structure). Second, we controlled for participants’ gender, race/ethnicity, and participation in Greek organizations and their parents’ educational levels, and examined the within-person associations of the two risky sexual behaviors with hedonistic outcome expectancies of condom use, anxiety about HIV/AIDS, and romantic involvement. Third, we employed a pattern-mixture approach (Hedeker & Gibbons, 1997) to test whether the presence of missing data caused by attrition had an influence on our substantive conclusions. A binary variable was created to indicate whether participants dropped out from the study (with the reference group being participants who provided data on all four measurement occasions). The main effect of this variable probed whether the missing data pattern differed in terms of the risky sexual behaviors, whereas the interaction effects between this variable and other substantive predictors (i.e., time and other personal and contextual factors) probed whether the missing data patterns moderated the effects of these predictors. Because retaining non-significant interactions tends to increase standard errors (Aiken & West, 1991), we only included significant interactions in all steps of the analyses (see Appendix for equations for the analytic model).

Results

Condom Use Inconsistency

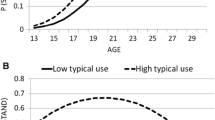

The first step of the analyses revealed significant fixed effects for the linear (γ10) and quadratic (γ20) components of time. In support of Hypothesis 1(a), on average, students’ condom use inconsistency increased over time, but the rate of change slowed toward the end of college (see Fig. 1). The second step of the analyses revealed significant within- (γ30) and between-person (γ06) effects of hedonistic outcome expectancies of condom use and a significant within-person effect of romantic involvement (γ50). In support of Hypothesis 2(a), students who had more negative hedonistic outcome expectancies, on average, used condoms less consistently, and at times when students held more negative hedonistic outcome expectancies than usual, they used condoms less consistently than usual. Moreover, in support of Hypothesis 2(b), at times when students were involved in a romantic relationship, they used condoms less consistently than usual. The third step of the analyses revealed no significant main or moderating effects of the missing data pattern, indicating that the substantive conclusions about condom use inconsistency were not sensitive to the presence of missing data. The non-significant interactions between the study completion variable and other predictors were removed from the model.

Sexual Encounters Involving Alcohol Use

The first step of the analyses revealed a significant fixed effect for the linear (γ10) component of time. In partial support of Hypothesis 1(b), on average, students reported more sexual encounters involving alcohol use over time (see Fig. 2). The quadratic time effect was not significant and was removed from the model. The second step of the analyses revealed a marginally significant (γ40, p = .05) within-person effect and a significant between-person (γ07) effect of anxiety about HIV/AIDS and a significant within-person effect of romantic involvement (γ50). In support of Hypothesis 3(a), students who were more anxious about HIV/AIDS, on average, had more sexual encounters involving alcohol use, and at times when students felt more anxious about HIV/AIDS than usual, they reported more sexual encounters involving alcohol use than usual. Moreover, in support of Hypothesis 3(b), at times when students were involved in a romantic relationship, they had fewer sexual encounters involving alcohol use than usual. The third step of the analyses revealed no significant main or moderating effects of the missing data pattern, and the non-significant interactions were removed from the model (for coefficients for the final models of the two risky sexual behaviors, see Table 2).

Discussion

Using multiple-wave, longitudinal data from college students, this study examined longitudinal changes and within-person variations in condom use inconsistency and sexual encounters involving alcohol use. Our results indicated that longitudinal changes in condom use inconsistency and sexual encounters involving alcohol use were, in general, predictable using the theory of emerging adulthood (Arnett, 2000). Moreover, consistent with a conceptual framework of sexual motives (Cooper et al., 1998), these two risky sexual behaviors were linked to different personal and contextual factors in unique ways.

Risky Sexual Behaviors Increased Over Time

As predicted by Hypothesis 1(a), condom use inconsistency increased and then leveled off over time. Emerging adulthood is a developmental period characterized by identity exploration, which may involve experimentation with risky behaviors (Ravert, 2009; Schulenberg & Maggs, 2002). A number of studies have examined longitudinal changes in condom use inconsistency, but the results are mixed. Capaldi et al. (2002) and O’Donnell et al. (2001) presented descriptive statistics that adolescents and emerging adults used condoms less consistently across time, but they did not test the trends statistically. Bauermeister et al. (2009) documented that condom use inconsistency increased significantly through adolescence and slowed toward emerging adulthood, but Bailey et al. (2011) found no significant changes in emerging adults’ condom use inconsistency after such background characteristics as gender and race/ethnicity were controlled for. Our study contributes to this work by providing statistical tests and showing that, consistent with Bauermeister et al. (2009)’s findings, condom use inconsistency followed a quadratic pattern of change in emerging adulthood. The discrepancies in findings among these and our studies may result from the use of different measures. Whereas a continuous measure of condom use inconsistency was used in Bauermeister et al.’s (2009) and our studies, a dichotomized measure based on whether the respondents had “always” engaged in condom-protected sex was used in Bailey et al.’s (2011) study. A continuous measure may be more able to capture the time-to-time variations in sexual experiences among emerging adults, and thus provide for more variance to explain and result in increased power to detect longitudinal changes. However, because researchers have just begun to study risky sexual behaviors using multiple-wave, longitudinal data, more empirical studies are needed to reconcile these findings.

In partial support of Hypothesis 1(b), sexual encounters involving alcohol use increased in a linear fashion across emerging adulthood. Our study was one of the first to investigate how sexual encounters involving alcohol use changed over time, and little empirical work is available for comparisons. However, the ability of our study to detect an eventual stabilizing or declining trend was limited by the study design. Because there was a 2-year gap between our last two measurement occasions and individuals are less likely to believe that alcohol would enhance sexual (Lundahl et al., 1997) and other (Sher et al., 1996) activities after age 20, we might have missed a peak in sexual encounters involving alcohol use in the second or third year of college. Another possibility is that, because our last measurement occasion was scheduled in the fall of the fourth year of college and the decline in alcohol use occurs at around the mid-20s (Schulenberg & Maggs, 2002), we might have documented a continued increase that would slow or reverse soon. Further studies should cover years spanning from emerging through early adulthood to fully examine longitudinal changes in risky sexual behaviors.

It is worth noting that the magnitude of the observed changes in risky sexual behaviors was modest. As indicated by some prior research, risky behaviors can be stable across time (Capaldi et al., 2002; Catalano & Hawkins, 1996). However, our results that risky sexual behaviors increased across the college years were consistent with a developmental perspective that, during the process of identity exploration, emerging adults may experiment with risky behaviors (Arnett, 2000). The finding that condom use inconsistency leveled off toward the end of college provided further evidence that such a process is time-prescribed. Because having a romantic partner becomes more common across adolescence and emerging adulthood (Meier & Allen, 2009), there is a tendency for researchers to understand longitudinal changes in risky sexual behaviors, especially condom use inconsistency, as an outcome of being involved in a romantic relationship (Lefkowitz et al., 2010). However, our analyses showed that the effects of time on risky sexual behaviors remained significant even when time-varying romantic involvement was included in the model, lending support to the utility of viewing risky sexual behaviors as a developmental phenomenon.

Risky Sexual Behaviors Were Associated With Other Personal and Contextual Factors

Hypotheses 2 and 3, which specified distinct associations between risky sexual behaviors and other personal and contextual factors, were supported by our results. Numerous studies have shown that individuals who believe that condoms interfere with sexual pleasure (e.g., Koniak-Griffin & Stein, 2006; O’Leary et al., 2005) and those who interpret condom use in an established relationship as a sign of mistrust (e.g., Greene & Faulkner, 2005; Umphrey & Sherblom, 2007) use condoms less consistently. There is also evidence that personal concerns about HIV/AIDS (Gerrard et al., 1996) and warm, affective relationships (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996; Cooper et al., 1998) are predictive of risky sexual behaviors.

The unique contribution of our study lies in the use of time-varying covariates that generate separate estimates of within-person and between-person effects. Specifically, it is not only that individuals with more negative hedonistic outcome expectancies used condoms less consistently, but that at times when individuals held more negative hedonistic outcome expectancies than usual, they used condoms less consistently than usual; it is not only that individuals with greater anxiety about HIV/AIDS had more sexual encounters involving alcohol use, but that at times when individuals felt more anxious about HIV/AIDS than usual, they had more sexual encounters involving alcohol use than usual; and at times when individuals were involved in a serious relationship, they used condoms less consistently and had fewer sexual encounters involving alcohol use than usual. By treating each individual as his or her own control, we excluded stable, third variables as alternative explanations and provided for stronger inferences about the relations between different personal and contextual factors and risky sexual behaviors (Curran & Bauer, 2011). Indeed, consistent with the idea that sexual behaviors serve a range of psychosocial functions (Cooper et al., 1998), our findings indicated that condom use inconsistency and sexual encounters involving alcohol use were linked to different factors in unique ways. Romantic involvement, for example, is positively associated with condom use inconsistency, but negatively associated with sexual encounters involving alcohol use. Future researchers should continue to explore the distinct correlates of different risky sexual behaviors.

Our findings also have potential implications for intervention. Given the high rates of risky sexual behaviors among emerging adults and the potential negative consequences of these behaviors (Cates et al., 2004; Jones et al., 2002), programs that promote safer sex are important for college students. It is often assumed that sex in an established relationship is safer than sex in casual encounters or concurrent relationships. However, sex with other partners while in an established relationship is not uncommon (Whisman & Snyder, 2007), STIs among young people are often asymptomatic and underdiagnosed (Weinstock, Berman, & Cates, 2004), and “established” relationships among emerging adults typically involve a series of sequential, short-term monogamous relationships (Lefkowitz et al., 2010), which also contribute to the spread of STIs (Kretzschmar, 2000). Health educators and providers could target romantically involved individuals, and help them develop the confidence and skills in negotiating condom use with a romantic partner. Beliefs about condoms and anxiety about HIV/AIDS are also changeable through education and testing, and could serve as the focus of intervention.

Limitations and Conclusions

Our study was not without limitations. First, our sample was not representative of all emerging adults in the United States. The difference in the embedding social contexts between college-attending and non-college-attending emerging adults has to be considered when generalizing our findings beyond college students. A related issue is that our sample only included heterosexual individuals, and thus our results may not apply to non-heterosexual individuals. Second, although the use of time-varying covariates allowed us to partial out the potential influences of stable individual differences (Curran & Bauer, 2011), conclusions about causal relations cannot be made based on a correlational study like ours. A theoretical framework on sexual motives (Cooper et al., 1998) led us to conceptualize different personal and contextual processes as potential causal factors, but there are alternative interpretations of our findings. Personal beliefs about condom use (Olson & Stone, 2005) and concerns about HIV/AIDS (Gerrard et al., 1996), for example, may reflect rather than motivate risky sexual behaviors. Intervention studies that use experimental designs to manipulate beliefs about condom use and concerns about HIV/AIDS are required to disentangle the causal paths underlying the associations documented in this study.

Finally, our measures of risky sexual behaviors did not consider the relationship contexts under which these behaviors occurred. Risky sexual behaviors do not automatically cause STIs or unintended pregnancies. Future studies on risky sexual behaviors should include more fine-grained measures of relational status and quality, sexual health history, and use of different prevention methods. Furthermore, our measure of sexual encounters involving alcohol use did not measure the amount of alcohol consumed or whether the use of alcohol actually led to riskier sexual decisions. Event-level analyses indicate that the association between alcohol use and risky sexual behaviors depends on situational factors, such as whether a primary or casual partner is involved (Scott-Sheldon, Carey, & Carey, 2010; Scott-Sheldon et al., 2009). An important direction for future research is to examine how risky sexual behaviors are linked to different personal and contextual factors at different levels of analysis (e.g., global, personal, and event).

Despite these limitations, to our knowledge, this study was the first to examine longitudinal changes in sexual encounters involving alcohol use and one of the few studies to examine within-person variations in condom use inconsistency. On a theoretical level, our use of the theory of emerging adulthood (Arnett, 2000) demonstrates the utility of a developmental perspective in understanding longitudinal changes in sexual behaviors. On an empirical level, our approach to analyze condom use inconsistency and sexual encounters involving alcohol use separately and use of time-varying covariates highlights the importance of studying the unique correlates of risky sexual behaviors (Cooper et al., 1998) and distinguishing between within-person versus between-person associations (Curran & Bauer, 2011).

Notes

To probe whether sexual encounters involving alcohol use would be better modeled using a non-linear approach, we also analyzed the data using the GLIMMIX procedure in SAS, specifying a log link function and Poisson-distributed residuals. Results based on the MIXED and GLIMMIX procedures were inferentially equivalent. For reasons of simplicity, both the two risky sexual behaviors were analyzed using the MIXED procedure.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469–480. doi:10.1037//0003-066X.55.5.

Bailey, J. A., Haggety, K. P., White, H. R., & Catalano, R. F. (2011). Associations between changing developmental contexts and risky sexual behavior in the two years following high school. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40, 951–960. doi:10.1007/s10508-010-9633-0.

Bauermeister, J. A., Zimmerman, M., Xue, Y., Gee, G. C., & Caldwell, C. H. (2009). Working, sex partner age differences, and sexual behavior among African American youth. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38, 802–813. doi:10.1007/s10508-008-9376-3.

Capaldi, D. M., Stoolmiller, M., Clark, S., & Owen, L. D. (2002). Heterosexual risk behaviors in at-risk young men from early adolescence to young adulthood: Prevalence, prediction, and association with STD contraction. Developmental Psychology, 38, 394–406. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.38.3.394.

Catalano, R. H., & Hawkins, J. D. (1996). The social development model: A theory of antisocial behavior. In J. D. Hawkins (Ed.), Delinquency and crime: Current theories (pp. 149–197). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Cates, J. R., Herndon, N. L., Schulz, S. L., & Darroch, J. E. (2004). Our voices, our lives, our futures: Youth and sexually transmitted diseases. Chapel Hill, NC: School of Journalism and Mass Communication, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Cooper, M. L. (2006). Does drinking promote risky sexual behavior? A complex answer to a simple question. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15, 19–23. doi:10.1111/j.0963-7214.2006.00385.x.

Cooper, M. L., Shapiro, C. M., & Powers, A. M. (1998). Motivations for sex and risky sexual behavior among adolescents and young adults: A functional perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 1528–1558. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.75.6.1528.

Curran, P. J., & Bauer, D. J. (2011). The disaggregation of within-person and between-person effects in longitudinal models of change. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 583–619. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100356.

DiClemente, R. J., Salazar, L. F., Crosby, R. A., & Rosenthal, S. L. (2005). Prevention and control of sexually transmitted infections among adolescents: The importance of a socio-ecological perspective. Public Health, 119, 825–836. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2004.10.015.

Fergus, S., Zimmerman, M. A., & Caldwell, C. H. (2007). Growth trajectories of sexual risk behavior in adolescence and young adulthood. American Journal of Public Health, 97, 1096–1101. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.074609.

Gagnon, J. H. (1990). The explicit and implicit use of the scripting perspective in sex research. Annual Review of Sex Research, 1, 1–43.

George, W. H., & Stoner, S. A. (2000). Understanding acute alcohol effects on sexual behaviors. Annual Review of Sex Research, 11, 92–124.

Gerrard, M., Gibbons, F. X., & Bushman, B. J. (1996). Relation between perceived vulnerability to HIV and precautionary sexual behavior. Psychological Bulletin, 119, 390–409. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.119.3.390.

Greene, K., & Faulkner, S. L. (2005). Gender, belief in the sexual double standard, and sexual talk in heterosexual dating relationships. Sex Roles, 53, 239–250. doi:10.1007/s11199-005-5682-6.

Guerrero, L. K., Spitzberg, B., & Yoshimura, S. (2004). Sexual and emotional jealousy. In J. H. Harvey, A. Wenzel, & S. Sprecher (Eds.), The handbook of sexuality in close relationships (pp. 311–345). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Ham, L. S., & Hope, D. A. (2003). College students and problematic drinking: A review of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review, 23, 719–759. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(03)00071-0.

Hedeker, D., & Gibbons, R. D. (1997). Application of random-effects pattern mixture models for missing data in longitudinal studies. Psychological Methods, 2, 64–78. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.2.1.64.

Jadack, R. A., Fresia, A., Rompalo, A. M., & Zenilman, J. M. (1997). Reasons for not using condoms at urban STD clinics. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 24, 402–407. doi:10.1097/00007435-199708000-00004.

Jemmott, L. S., & Jemmott, J. B. (1992). Increasing condom use intentions among sexually active Black adolescent women. Nursing Research, 41, 273–279. doi:10.1097/00006199-199209000-00004.

Jones, R. K., Darroch, J. E., & Henshaw, S. K. (2002). Contraceptive use among U.S. women having abortions in 2000–2001. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 34, 294–303. doi:10.2307/3097748.

Koniak-Griffin, D., & Stein, J. A. (2006). Predictors of sexual risk behaviors among adolescent mothers in a human immunodeficiency virus prevention program. Journal of Adolescent Health, 38, 297.e1–297.e11. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.12.008.

Kotchick, B. A., Shaffer, A., Forehand, R., & Miller, K. S. (2001). Adolescent sexual risk behavior: A multi-system perspective. Clinical Psychology Review, 21, 493–519. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(99)00070-7.

Kretzschmar, M. (2000). Sexual network structure and STD prevention: A modeling perspective. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 27, 627–635. doi:10.1097/00007435-200011000-00011.

Lefkowitz, E. S., Gillen, M. M., & Vasilenko, S. A. (2010). Putting the romance back into sex: Sexuality in romantic relationships. In F. Fincham & M. Cui (Eds.), Romantic relationships in emerging adulthood (pp. 213–233). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Lundahl, L. H., Davis, T. M., Adesso, V. J., & Lukas, S. E. (1997). Alcohol expectancies: Effects of gender, age, and family history of alcoholism. Addictive Behaviors, 22, 115–125. doi:10.1016/S0306-4603(96)00022-6.

Meier, A., & Allen, G. (2009). Romantic relationships from adolescence to young adulthood: Evidence from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Sociological Quarterly, 50, 308–335. doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.2009.01142.x.

Moilanen, K. L., Crockett, L. J., Raffaelli, M., & Jones, B. L. (2010). Trajectories of sexual risk from middle adolescence to early adulthood. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 20, 114–139. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00628.x.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2010). The condition of education 2010. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/FastFacts/display.asp?id=16.

Nettleman, M., Brewer, J., & Ayoola, A. (2007). Reasons for unprotected intercourse in adult women: A qualitative study. American College of Nurse-Midwives, 52, 148–152. doi:10.1089/jwh.2007.0210.

O’Donnell, L., O’Donnell, C. R., & Stueve, A. (2001). Early sexual initiation and subsequent sex-related risks among urban minority youth: The Reach for Health Study. Family Planning Perspectives, 33, 268–275. doi:10.2307/3030194.

O’Leary, A., Hoff, C. C., Purcell, D. W., Gómez, C. A., Parsons, J. T., Hardnett, F., & Lyles, C. M. (2005). What happened in the SUMIT trial? Mediation and behavior change. AIDS, 19(Suppl. 1), S111–S121. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000167357.94664.10.

Olson, J. M., & Stone, J. (2005). The influence of behavior on attitudes. In D. Albarracín, B. T. Johnson, & M. P. Zanna (Eds.), The handbook of attitudes (pp. 223–271). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

O’Malley, P. (2004). Maturing out of problematic alcohol use. Alcohol Research & Health, 28, 202–204.

Pascarella, E. T., & Terenzini, P. T. (2005). How college affects students. Vol. 2: A third decade of research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Raudenbush, S. W., & Bryk, A. S. (2002). Hierarchical linear models. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ravert, R. D. (2009). “You’re only young once”: Things college students report doing now before it is too late. Journal of Adolescent Research, 24, 376–396. doi:10.1177/0743558409334254.

Schafer, J. L., & Graham, J. W. (2002). Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods, 7, 147–177. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.7.2.147.

Schulenberg, J. E., & Maggs, J. L. (2002). A developmental perspective on alcohol use and heavy drinking during adolescence and the transition to young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 14, 54–70.

Scott-Sheldon, L. A., Carey, M. P., & Carey, K. B. (2010). Alcohol and risky sexual behavior among heavy drinking college students. AIDS and Behavior, 14, 845–853. doi:10.1007/s10461-008-9426-9.

Scott-Sheldon, L. A., Carey, M. P., Vanable, P. A., Senn, T. E., Coury-Doniger, P., & Urban, M. A. (2009). Alcohol consumption drug use, and condom use among STD clinic patients. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 70, 762–770.

Sheeran, P., Abraham, C., & Orbell, S. (1999). Psychosocial correlates of heterosexual condom use: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 90–132. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.125.1.90.

Sher, K. J., Wood, M. D., Wood, P. K., & Raskin, G. (1996). Alcohol outcome expectancies and alcohol use: A latent variable cross-lagged panel study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 105, 561–574. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.105.4.561.

Snell, W. E., & Finney, P. (1996). The multidimensional AIDS anxiety questionnaire. Unpublished manuscript.

Stoner, S. A., George, W. H., Peters, L. M., & Norris, J. (2007). Liquid courage: Alcohol fosters risky sexual decision-making in individuals with sexual fears. AIDS Behaviors, 11, 227–237. doi:10.1007/s10461-006-9137-z.

Umphrey, L., & Sherblom, J. (2007). Relational commitment and threats to relationship maintenance goals: Influences on condom use. Journal of American College Health, 56, 61–67. doi:10.3200/JACH.56.1.61-68.

Weinstock, H., Berman, S., & Cates, W., Jr. (2004). Sexually transmitted diseases among American youth: Incidence and prevalence estimates, 2000. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 36, 6–10. doi:10.1363/3600604.

Whisman, M. A., & Snyder, D. K. (2007). Sexual infidelity in a national survey of American women: Differences in prevalence and correlates as a function of method of assessment. Journal of Family Psychology, 21, 147–154. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.21.2.147.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development to Eva S. Lefkowitz (R01-HD41720). We would like to thank Sandra Abarca, Jill Boelter, Lauren Dietz, Jennifer Fang, Graciela Espinosa-Hernandez, Meghan Gillen, Shelley Hosterman, McKenzie Jones, Emily Killoren, Casey O’Neil, Annie Pezella, Cindy Shearer, and Tara Stoppa for their help in data collection and management.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Equations for Multilevel Models of Risky Sexual Behaviors

Level 1 equation.

Level 2 equations.

Note. WP = within-person; BP = between-person. Residual terms are absent for variables treated as fixed. Subscript i indicates occasions within individual j, and j indicates individuals.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lam, C.B., Lefkowitz, E.S. Risky Sexual Behaviors in Emerging Adults: Longitudinal Changes and Within-Person Variations. Arch Sex Behav 42, 523–532 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-012-9959-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-012-9959-x