Abstract

The history of mental health care has been marked by various struggles in maintaining the dignity of service users. Some reform movements have started to use educational strategies aimed at the beliefs and attitudes of professionals, as well as changing the way that practice is carried out. This paper intends to systematically review and synthesize studies assessing awareness and training activities for mental health professionals covering aspects related to recovery, empowerment, and in general, rights-based care to achieve full citizenship of mental health services users. We reviewed 26 articles and were able to include 14 of them in meta-analytic calculations. Our results at the qualitative level show an evolution of the literature towards better quality designs and focus on aspects related to the impact and maintenance of the effects of these training activities. Meta-analytic calculations found high heterogeneity but no risk of biases and low-to moderate effect sizes with a statistically significant impact on beliefs and attitudes but not on practices. The importance of this information in improving and advancing these educational activities is addressed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Since Pinel released the chains of the Bicêtre and Salpêtrière inmates, until the recent recovery movement, the history of mental health care has been marked by various struggles in preserving the dignity of service users (Goldman and Morrissey 1985). At the end of the 18th century, the appearance of some illustrious patients, including King George III in the UK and Jean-Baptiste Pussin (an ex-patient turned in Bicêtre Hospital-superintendent and Pinel’s collaborator) and his wife Margueritte Jubline, marked the inauguration of the first humanitarian reform (Schuster et al. 2011). In the mid-19th century the UK Alleged Lunatics’ Friend Society, founded by people with internment experience carried out what may be considered the first organized political lobbying and rights advocacy campaign for people confined in psychiatric hospitals (Hervey 1986). Six decades later, Clifford Whittingham Beers founded the US National Committee for Mental Hygiene after having been confined to a mental institution where he witnessed serious maltreatments. The twentieth century witnessed how the anti-psychiatry, community mental health, and psychiatry survivors movements once again exposed the humiliations that were experienced in psychiatric care, giving way to the psychiatric deinstitutionalization process. This institutional transformation, although reduced coercive measures and long-term hospitalization, failed to provide enough outpatient and rehabilitative psychosocial services to replace the old interment system. The influence of the biopsychosocial model (Bachrach 1993) and the efforts of community-oriented professionals should have been promising, but lack of funding and increased investment in biomedical-oriented services had detrimental effects on the deinstitutionalization process. For instance, the lack of funding for the process led to an increase in the number of homeless people with mental disorders (Lamb 1984).

It could be said that in all these struggles, two or more truths about the nature and treatment of mental disorders were at stake (Bracken and Thomas 2001). Indeed, the question of power has been highly relevant in the history of mental health care (Rose 1989), not only because of the violence that was tolerated by the biomedical establishment, but also due to the influence of the pharmaceutical industry. This has been the main object of struggle for reform movements. Additionally, some paradigmatic changes occurred when senior professionals sympathized with changes driven by consumer organisations. Examples of this have accompanied the evolution of psychiatric care, from Pinel himself to contemporary reformists involved in the international recovery and other allied user-led movements.

Recently, mental health consumers/(ex-) users/survivors’ groups, the recovery movement and the various campaigns against stigma at the global level have moved away (to varying degrees) from the struggle for a unique truth about mental health. Similarly to cultural competence (Comstock et al. 2008), a greater focus has been placed on the need for rights-based care through advocacy, as well as reflection and training of mental health professionals. These activities are focused not only on the stigma and discrimination that mental health service users often confront but also the need to empower them to make shared decisions and the need to adapt concepts used in general biomedicine to a field with many peculiarities and very specific psychosocial needs.

This new notion and strategy is reflected in the emergence of the literature on changes in the beliefs and attitudes of mental health professionals (Hansson et al. 2013; Ponce et al. 2016), in contrast to the literature on deinstitutionalization that strongly focused on structural changes. Campbell and Gallagher (2007) carried out the first literature review on recovery training in mental health practice. They analysed a total of 30 educational interventions. Their findings point to a very heterogeneous inter-professional environment with a preponderance of experiential and reflective training activities combined with traditional teaching methods. They also stressed the importance of participation from service users and their relatives in these training experiences. In this regard, Repper and Breeze (2007) summarise user involvement in the education of health professionals, emphasising interpersonal skills, respect and humanistic qualities of caring, in contrast with practitioners’ preferences for technical skills. In a conceptual review, Mabe et al. (2016) offer an overview of the contents of recovery-oriented training activities for clinicians. Starting from the recovery principles, all of them include the promotion of attitudes that support recovery-oriented care such as the elimination of stigmatizing views of individuals diagnosed with mental disorders, viewing patients as equal partners in their care and introducing recovery-oriented practices such as methods for instilling hope, identification of strengths or empowerment. In addition, many of them include individuals with a lived experience of mental illness as trainers. Using a rapid realist review methodology, Gee et al. (2017) identified factors contributing to lasting change in practice following recovery-based training interventions for inpatient mental health rehabilitation staff. They reviewed fifty-one documents based on 49 training experiences. Their findings point out the need to implement collaborative action plans and regular meetings, appointing change agents, explicit management endorsement and prioritization and modifying organizational structures to achieve lasting change. A recent narrative review (Jackson-Blott et al. 2019) yielded similar conclusions and stressed the need to incorporate recovery-oriented training within organisational changes to guarantee its translation into clinical practice.

So far, to the best of our knowledge, no systematic review or meta-analysis of the literature on recovery training has been carried out. The purpose of this study is to systematically review and meta-analyse this information to provide an overview of the effectiveness of recovery training, as well as the best strategies to achieve change in different professional contexts. The topics covered in the present work are aspects related to empowerment, recovery, shared decision-making, stigma and in general rights-based care, in order for mental health services users to achieve full citizenship.

Methods

We adhered to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al. 2009). We registered the review in PROSPERO (Code CRD42017062561).

Eligibility Criteria for the Systematic Review

For this systematic review, we considered empirical reports on recovery training addressed to mental health professionals involved in the treatment of mental health symptoms including clinical psychologists, general practitioners, psychiatrists, nurses, social workers, peer support staff as well as students in these disciplines.

We discarded articles exclusively dealing with stigma or seclusion and restrain measures due to the existence of recent comprehensive reviews (Goulet et al. 2017; Gronholm et al. 2017; Henderson et al. 2014).

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for the Meta-analysis

In terms of participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes and study design (PICOS) the key inclusion criteria were; participants—mental health practitioners; interventions—recovery or psychosocial rehabilitation training programmes designed for promoting changes in knowledge, attitudes and practice based on recovery principles; comparisons—intervention versus control or post versus pre; outcomes—recovery-based knowledge, attitudes and practices; and study design—randomised, quasi-experimental and before-and-after/pre-post designs.

Exclusion criteria: qualitative measures, cross-sectional or retrospective, measuring change in consumers, professionals outside the mental health field, indistinct reporting of consumers and professionals’ outcomes.

Data Sources and Search Terms

We searched the academic databases PsycINFO, MEDLINE, Google Scholar and Scopus with the objective of finding academic literature; but we also searched in regular search engines such as Google and Bing, with the aim of finding grey literature on the subject.

Due to the heterogeneity of the reviewed subjects, several series of systematic reviews of terms were carried out. The search terms included seminar, teaching, training, or workshop; combined with keywords such as citizenship, human rights, empowerment, person-centred, recovery, shared decision-making, stigma; and classical professional terminology such as psychiatry, psychiatric care, psychology, psychotherapy, social work, social education, nursing and peer support. A more detailed explanation of search terms and strategies can be found in the Appendix. We also used a snowballing strategy building on the references of each article that was previously added. All these strategies were repeated until no relevant new articles were found.

Meta-analytic Data Extraction Process

The following variables were extracted from each paper by the first and second authors: occupation of participants; size of the experimental sample; size of the control sample, nature of the control condition; percentage of females, type and length of educational intervention; main outcomes; and the mean and standard deviations of these main outcomes. The outcomes of interest were grouped in three conceptual domains: (a) knowledge of recovery principles, (b) recovery attitudes and (c) recovery-based practice.

Quality Assessment

The quality assessment tool for quantitative studies (QATQS; National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools 2008) was used to assess the quality of the studies (see Table 2). QATQS assesses methodological rigor in six areas: (a) selection bias; (b) design; (c) confounders; (d) blinding; (e) data collection method; and (f) withdrawals and dropouts. QATQS scoring was conducted independently by both authors. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion with agreement reached in all cases. Details of the QATQS scoring can be found in Table 2.

Statistical Analyses

We used the meta package (Schwarzer et al. 2015) for the R software (R Core Team 2018) to calculate the statistical analyses and create both forest and funnel plots. To assess publication bias, we used contour-enhanced funnel plots and Begg and Mazumdar (1994) tests by outcome valence. We used random effects models to calculate effect sizes due to the anticipation of methodological heterogeneity between studies in some outcomes. As most studies reported means and standard deviations, different scales were grouped under a common outcome type (knowledge, attitudes and practice) and we calculated standardized mean differences (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals for each outcome (Sedgwick and Marston 2013). In case of adding a negative valence scale to an asset-based outcome, we recoded the means (multiplied by minus one) so that the valences coincided. For studies with more than one scale in the same outcome group, we converted mean values for each of these measures to a single mean value for the intervention and control groups respectively. We computed the variance of the mean among scales enclosed within the same outcome grouping using Borenstein et al. (2009) method:

when the correlation between scales was unknown, we assumed r = .5 as a midpoint between total independence and total dependence. For the weighted parameters, we excluded one study with active control arms (Williams et al. 2016). This was necessary to preserve the statistical independence of assumptions, so the risk of bias due to the inflation of the overall effect size’s variance could be controlled. Heterogeneity was systematically assessed among the studies using the Cochran’s Q, I2 and the τ2 statistics. Cochran’s Q, is a Chi squared distributed measure of weighted squared deviations. It can be converted into a p value and is the usual heterogeneity test statistic. Meanwhile, the principal advantage of the I2 parameter, the proportion of the observed variance reflecting real differences in effect size, is that it can be calculated and compared across meta-analyses of different sizes, of different types of study, and using different types of outcome data (Higgins et al. 2003). Finally, τ2 is the random effects variance of the true effect sizes. Regarding moderator analyses, for each outcome, we gathered variables with possible effects on the impact of interventions (De Rijdt et al. 2013; Mansouri and Lockyer 2007). We included year of publication, percentage of females, age, duration of intervention, time between pre and post evaluations, QATQS score and active arm sample size as covariates. Study design (randomised vs. non-randomised) could only be tested for the practice outcomes as we followed Higgins and Green’s (2011) minimum of three studies for inclusion recommendation.

Results

Study Selection

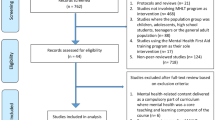

The search of PsycINFO, MEDLINE, Google Scholar and Scopus databases provided a total of 836 articles and 15 more were added through snowballing. After removing duplicates, 823 remained, of which 52 included information on concrete trainings. Eight studies only included narrative information that has been used throughout this paper. Another eight studies were also excluded from the systematic review as they included training activities aimed at objectives different from those of the recovery movement. Five studies did not include any evaluation information, four were evaluating systemic or user-centred outcomes and one was an extended report of a published paper. After excluding these 26 documents, we included in the systematic review 26 articles reporting any kind of information about the evaluation of the effectiveness of these training activities.

Finally, 14 studies included pre-post, quasi-experimental or experimental designs, excluding a study with just active arms (Williams et al. 2016), were included in the meta-analysis. Figure 1 offers a flow diagram of the search and inclusion process.

Study Characteristics

Table 1 offers an overview of the studies included in the systematic review. In the results section, we provide a summary of each project and the type of training activities that were carried out.

The majority of studies took place in Europe (mainly United Kingdom), Oceania (Australia and New Zealand) and The United States. Other countries involved were Israel and Canada. Only one study included undergraduate students, and six studies were carried out in the context of mental health inpatient facilities. Sample sizes were diverse, ranging from 12 to 342 participants per group. Regarding the training curriculum, nine studies used their own design course; the majority used short duration workshops (most of them lasting 2–4 days). Regarding outcomes, most studies reported quantitative measures, while four exclusively included qualitative assessments.

Risk of Bias in Individual Studies (QATQS)

Of the 26 studies included in the systematic review, four were qualitative. Of the remaining 22, three (14%) were considered strong, six (27%) moderate and 13 (59%) weak. The greatest weaknesses were associated to blinding (it was considered that outcome assessors were aware of the intervention status of the participants and in fifteen studies the study participants were aware of the research questions) followed by attrition and confounders control (considered to be high and nil in six studies respectively). In contrast, all studies used measures with adequate properties and most, except for three, were designed with some type of control, at least through cohorts. Table 2 shows all the outcomes of the QATQS process.

Historical Overview

The recovery movement was linked to the psychiatric rehabilitation movement, which originated within the deinstitutionalization process. One of the main differences is probably the recovery’s intention of changing services where the rehabilitation philosophy had not had any influence, including inpatient facilities (Singh et al. 2016). The recovery movement was deeply influenced by community rehabilitation ideas present in former movements such as assertive community treatment, that also gave importance to the training of professionals from its foundation (Felton et al. 1974). Indeed, slightly before the recovery movement started, Cook et al. (1995) published a randomized evaluation of training activities for mental health service providers carried out by consumers or non-consumers.

The first recovery project which published specific information about practitioner training was the New York State Office of Mental Health’s Core Curriculum training program (Way et al. 2002). The pre-post evaluation of this programme included almost 4000 practitioners. Results showed statistically significant increases in communication and interaction, respect for recipients of inpatient care, and increases in cultural competence levels.

Young et al. (2005) presented a consumer-led staff supporting skills for self-help intervention. The intervention included education, clinician-client dialogues, ongoing technical assistance, and support from self-help. They evaluated the intervention’s impact on clinicians’ competencies, care processes, and the formation of mutual support groups through a one-year randomised controlled trial. Results showed statistically significant improvements in education regarding care, rehabilitation methods, natural support, holistic approaches, teamwork, overall competency, and recovery orientation for participants who received the intervention.

Crowe et al. (2006) introduced the concepts of hopefulness and optimism to this field of research. They examined the impact of a two-day recovery-based training program based on the collaborative recovery model (Oades et al. 2005) at the University of Wollongong, Australia. Using a pre-post-training design, they found improvements in staff attitudes and hopefulness as well as an increase in knowledge regarding recovery and beliefs on the effectiveness of its components.

Doughty et al. (2008) implemented a wellness recovery action plan (WRAP; Copeland 2002) workshop in New Zealand. WRAP is a program designed and delivered by consumers to help both trained consumers (peer support workers) and practitioners to assist people in managing ill health. They examined the impact of a 2-day workshop using a pre-post design in a sample that mixed mental health professionals and consumers. Positive changes were found in knowledge and attitudes towards recovery principles. Participants also declared that the workshops were useful for their support work. Afterwards, A. Higgins (Higgins et al. 2012) implemented the same program in an Irish population also evaluating it through a pre-post design. They compared the differential effectiveness of a 2-day or a 5-day program in another mixed sample of mental health consumers and practitioners, replicating previous positive results for both modalities, and showing no different results between them.

Pollard et al. (2008) created their own workshop to deliver the principles of recovery in an inpatient setting in Israel. The evaluation of this project was done using a randomised clinical trial (RCT). The training significantly increased positive beliefs about recovery and knowledge of evidence-based practice treatments within a hospitalization context.

Meehan and Glover (2009) delivered a consumer-led recovery-training program in Queensland (Australia). This study employed a non-equivalent control group design. Three health service districts/regions from within were selected for training, whilst a fourth district was used as a comparison site. The 3-day workshop focused on knowledge and training of recovery-oriented clinician skills. The intervention group showed positive changes in the understanding of recovery principles and they were maintained at the six-month follow-up.

Psychiatry departments in the state of Georgia in the United States made considerable efforts to promote a holistic change to their institution based on recovery principles and created the Georgia Recovery-based Educational Approach to Treatment (GREAT; Ahmed et al. 2013). This project is based on the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration recovery concept (SAMSHA 2012), articulated in the principles of empowerment, hope, holistic care and support and emphasizes the importance of a certified peer specialist in joining departments in order to facilitate change (Mabe et al. 2014). Peebles et al. (2009) evaluated the effectiveness of the program, delivered in short workshops. They used a non-equivalent control group, pre-post-training design. Their results showed statistically significant improvements in knowledge and partial changes to positive attitudes to recovery. However, they could not control its translation to practice.

Using a pre-post design; Salgado et al. (2010) found improvements in recovery knowledge, attitudes, hopefulness and optimism after a two-day training programme carried out in New South Wales, Australia. They also found that attitudinal improvements following formal recovery training were not dependent on baseline levels of dispositional hope.

Tsai et al. (2010) conducted a quasi-experimental longitudinal study in two hospitals in the United States comparing specific/practical skills training with general/inspirational training and a control condition. An increase in agency recovery attitudes were found for staff who received specific/practical training than for staff who only received general/inspirational training or who did not receive any training. They also found a dose-dependent effect with higher effects for professionals who received more hours of training. The same research group (Tsai et al. 2011) carried out a cross-sectional retrospective study in four community mental health centres, confirming the previously proposed dose-dependent effect. Recovery-related training amount was related to higher scores on personal optimism, consumer optimism, and agency recovery orientation towards consumer life goals.

Strating et al. (2012) was conducted in The Netherlands which involved a first team-level multiple case study of Recovery training. Their pre-post study focused on long-term mental health care settings. They explored the effectiveness of ‘quality improvement collaborative groups’ in terms of objective outcome indicators and the impact of changes as perceived by team members, as well as the associations between collaborative-organizational- and team-level factors and perceived effectiveness. Their results indicated that innovative attributes, appropriate measures, usable data collection tools and an innovative team culture could explain variations in perceived effectiveness. An additional study also conducted in The Netherlands investigated the effectiveness of a recovery-oriented training program on knowledge and attitudes (Wilrycx et al. 2012). This quasi-experimental study demonstrated the effectiveness of intensive sessions separated in time using a complex implementation and follow-up system.

A King’s College-based group has carried out a series of evaluations of recovery-orientated practice adding for the first time behavioural intent measures. After a first approximation (Gilburt et al. 2013), they implemented a large-scale RCT consisting of a 1-year team-level intervention targeting staff behaviour to increase the focus on values, preferences, strengths and goals of patients with psychosis (REFOCUS; Slade et al. 2015). The authors did not find statistically significant differences between teams in their patients’ recovery process, although high participation was related to higher staff-rated scores for recovery-promotion behaviour change and patient-rated interpersonal recovery. They also found a saving of £1062 for each patient treated within teams that had received the intervention. A qualitative evaluation on the possible implementation barriers of the same project (Leamy et al. 2014) yielded two main themes: ‘Organisational readiness for change’ and ‘Training effectiveness’. ‘Organisational readiness’ was analysed at different ecological levels, evidencing barriers such as lack of time or heterogeneous leadership, perception by professionals that what they do is already recovery-based or insufficient preparation for participation. Training effectiveness included engagement strategies (including validation of previous knowledge), delivery style (with preference for practice-based activities) and modelling recovery principles (use of strengths-based approaches within the activities). The REFOCUS manual has influenced projects elsewhere. A project in Switzerland made an adaptation of the manual to implement a program delivered to mental health nurses in the context of acute psychiatric units (Zuaboni et al. 2017). The authors developed specific training sessions to enhance practical implementation of recovery principles during a period of nine months. However, they did not find statistically significant differences within the control group. Among the limitations of the study, the authors pointed out the need of involving the full multidisciplinary team in training and produce organisational changes to ensure implementation of recovery-based practice.

Similarly, in England a national research project carried out in inpatient facilities developed the rehabilitation effectiveness for activities for life consumer-led program (REAL, Cook et al. 2016) aimed at improving the willingness of professionals to promote change in the users’ engagement in structured activities. The training is focused on users with complex and severe mental health problems. The cluster-randomised controlled trial evaluation assessed change within a large-scale 1-year team-level intervention (GetREAL), which also evaluated direct costs and cost-effectiveness of care (study protocol in Killaspy et al. 2013). After the intervention, the users engagement in activities did not differ in comparison with a control group. In addition, researchers did not investigate whether the intervention caused behavioural changes in the staff that belonged to the intervention group (Killaspy et al. 2015). A further qualitative analysis (Lean et al. 2015) showed that despite the fact that participating staff received the intervention with enthusiasm, the changes it promoted could not be maintained after it ended. Reasons for this reversion to the previous state were lack of resources due to the economic recession, insufficient engagement with the intervention team and organisational limitations such as lack of senior staff support. Later analyses (Bhanbhro et al. 2016) explored possible mechanisms of maintaining long-term change in recovery-based practice, the mechanisms of change identified involved developing action plans collaboratively with staff and users, frequent group supervisions, implementing recovery-based plans in ongoing programmes in organisations and direct support of management and organisation in implementing recovery changes. All these measures, the authors argue, would assist staff in changing their practices.

A recent study focused on inpatient nurses (Repique et al. 2016), reported a mixed methods (pre-post questionnaires plus focus groups analysed through thematic analysis) evaluation of a webinar-based education programme. No differences were found in pre-post recovery knowledge or reduced restraint rates. The authors discuss the possibility that self-selection bias has influenced the results as high levels of knowledge were found at baseline.

Williams et al. (2016) analyse in depth, using a cluster-randomised controlled trial, the possible influence that professionals’ autonomy perception has on recovery values-based training. They hypothesise that staff subject to change would be more motivated to implement changes if trainings targeted their core professional values, thus introjecting the recovery philosophy. Results demonstrated that a single structured values clarification exercise promoted integrated motivation for changed practice and resulted in increased implementation planning.

Recent studies have included supervision sessions as a complement to workshops of short duration as a means of maintaining the changes that have been achieved and ensuring the recovery skills are put into practice. Deane et al. (2018) carried out a pre-post-repeated measures study based on a strengths-model based intervention. Their results at post-workshops evidenced gains in recovery and attitudes. However, almost none of these results were sustained at follow-up after supervision groups, with the exception of an improvement in willingness to assist consumers to pursue goals that require in positive risk taking. Overall, there was no improvement in recovery-based skills at follow-up. The authors suggested preliminary evidence of positive dose-dependent effects of gaining skills with attendance to supervision groups. However, one of their main limitations was the overall infrequent number of supervision sessions attended by practitioners. The authors suggest strategies to increase the retention of practitioners in the supervision sessions.

To our knowledge, the most recent and ongoing trial is held in Australia, known as the Principles Unite Local Services Assisting Recovery (PULSAR) study, with a version for primary care settings (Enticott et al. 2016) and one for community mental health centres (Shawyer et al. 2017). This is a 4-year long project, also inspired by the REFOCUS British intervention (Slade et al. 2015), aimed at implementing recovery-based practice in mental health specialised staff. The training consists of 2-day workshops addressed to staff and team manager levels. In addition, it includes voluntary monthly supervision sessions to maintain expected changes. The evaluation design is a cluster randomized controlled trial. The main outcomes are measured in consumers, such as degree of participation and personal recovery. Planned outcomes in staff and organisations are participation levels, intervention dosage and economic costs. Qualitative measures are also considered, which will explore from the intervention both staff and consumer views, as well as possible moderators of its effectiveness.

Synthesis of Results (Meta-analysis)

Risk of Reporting Bias

Figure 2 shows a Funnel plot of the included outcomes. Overall, there is no clear evidence of reporting bias. With the exception of two outlier outcomes, by observation of the funnel plot did not show a clear asymmetry. Begg and Mazumdar’s (1994) tests showed no statistically significant asymmetry (z = .825, p = .409).

Change in Knowledge of Recovery Principles

Recovery training appears to have an impact upon knowledge, as shown in Fig. 3 below. There was an overall moderate effect size of 0.52 (95% CI 0.21–0.83, p = .001), with all studies showing SMD values over zero, although the confidence interval of some did, which suggests that knowledge of recovery increased after interventions. Heterogeneity showed statistical significance (I2= 88%, τ2= .211, χ2 = 76.71, p < .01).

Moderator analyses

Studies’ publication year (Q(1) = 12.86, p = .0003) and gender proportion (Q(1) = 8.46, p = .0036) moderated results. Publications that have been published more recently and with more female participation showed lower intervention effects.

Change in Recovery Attitudes

Regarding attitudes, the influence of interventions was higher, as shown in Fig. 4 below. In this case, the effect size was 0.64 (95% CI 0.36, 0.92, p < 0.0001), suggesting that attitudes to recovery improved after interventions. Again, heterogeneity showed statistical significance (I2= 86%, τ2= .150, χ2 = 57.22, p < .01).

Moderator Analyses

The time from pre to post (Q(1) = 4.36, p = .037), gender proportion (Q(1) = 9.79, p = .002) and mean age (Q(1) = 5.65, p = .018) moderated the results. Studies with longer assessment latency, a higher proportion of females and older participants, showed lower effects in attitudinal change.

Change in Recovery-Based Practice

Interventions did not have an impact on practice, as shown in Fig. 5 below. The effect size was 0.26 (95% CI − 0.23, 0.74, p = .304) which was not statistically significant. In this analysis, heterogeneity also showed statistical significance (I2= 88%, τ2= .364, χ2 = 51.39, p < .01).

Moderator Analyses

Change in practice levels were predicted by the methodological quality of the studies (Q(1) = 4.39, p = .036). Quality correlated negatively with intervention effects.

Discussion

After several decades of influencing public mental health policies (Anthony 1993; Jacobson and Curtis 2000; Slade et al. 2014), the implementation of recovery-based services continues to be a pending issue in many territories and at certain care levels, especially hospital-based facilities (Singh et al. 2016). One of the main reasons for these obstacles is the lack of recovery-related concepts in the training of professionals (Silverstein and Bellack 2008). To reverse this situation, various training programmes have been carried out. In this work, we have reviewed articles carrying out assessments of these training activities. We found 26 studies and were able to include 14 of them in our meta-analytic calculations.

Qualitative results show an evolution of the literature focusing towards better quality designs and on aspects related to the impact and maintenance of the effects of these training activities. Regarding measuring instruments and strategies, an evolution is apparent between studies that have exclusively focused on knowledge and attitudes to more ambitious designs in which the impact of training activities in real practice is measured, not without great difficulties. In this sense, great value is given to the organisational changes necessary to carry out changes in the direction proposed by the recovery movement. Changing beliefs and attitudes can be a sterile effort if the organisational structure does not allow a real change to practices. Organisational barriers, but also opportunities, have been a recurrent issue in qualitative studies nested to two main randomised trials analysed in this review, namely the REFOCUS (Leamy et al. 2014) and GetREAL (Bhanbhro et al. 2016; Lean et al. 2015) projects. Tensions between ‘top down’ administrative-directed change and ‘bottom up’ or practitioner and team-level change are discussed in these secondary qualitative analyses. In the mentioned trials, although the intention was to carry out organisational changes from the bottom-up (Leamy et al. 2014), it is evident that practitioners involved had serious doubts that there was institutional commitment to carry out real changes. This connects with other concepts that have been addressed at the individual level such as hopefulness and autonomy. Some of these projects try to systematise and implement on a large-scale basis changes that first occurred spontaneously in an environment of consumer and professional militancy. As it happened with the achievements of other social movements, systematizing bottom-up processes, even when considering idiosyncrasies, implies some contradictions such as the difficulty to emulate the intrinsic motivation that the original movement had obtained. This seems to occur in a context in which institutions send contradictory messages. On the one hand, these institutions allocate funds to projects of this type, but on the other, they do not give real support so that changes can occur and be maintained.

Quantitative results, quite conditioned by the heterogeneity of the studies analysed, show no evidence of reporting bias and low to moderate effect sizes. Statistically significant results with moderate effect sizes were found for knowledge and attitudes while no statistically significant results and a low effect size were found for practise. These results are in line with what was found in the qualitative synthesis. From the staff perspective, it seems clear that the integration of knowledge and attitudes based on the recovery movement claims could be considered an essential component within the general principles and values of any mental health professional. Relatedly, adopting recovery-based attitudes may lead to therapeutic optimism (Deane et al. 2018) and might decrease unmet needs for service users (Slade et al. 2015). However, it can be seen that, although it is relatively easy to have an impact on certain prejudices and attitudes, it is not so easy for organizational changes to be made so that practices can be developed in a different way.

Intervention effects were moderated by publication year (knowledge), the proportion of female participants (knowledge and attitudes), assessment latency (attitudes), age (attitudes) and the methodological quality of the studies (practices). It might seem logical that studies that are more recent (focused on more concrete aspects, as we have seen), with higher quality in their designs including longer time from pre to post, and those with older participants have smaller effects. The first studies, focused on knowledge and with short-term follow-ups in many cases, showed an impact that is difficult to find in the large randomized trials carried out recently in which an attempt is made to measure impact on practice. Regarding the smaller impacts on staff with older ages, it may be that, due to more professional experience, they have more positive attitudes towards mental health patients, so changes are smaller, as they start from higher levels of recovery-based attitudes. The lower change found within female participants was consistent within two of the outcomes analysed. This result requires a more detailed analysis considering gender differences in power imbalance (women are less likely to be in positions of responsibility which makes it very difficult to differentiate if the effect was due to differences in gender or to institutional power imbalances). Similar gender differences have been found in outcomes such as procedural justice (Caldwell et al. 2009; Sweeney and Mcfarlin 1997) and corporate value change (Hebson and Cox 2011), implying that what sometimes is attributed to gender differences sometimes is in reality related to power imbalances. It is also possible that females feel more connected from the beginning with the concepts of recovery and, therefore, changes are smaller since they begin having a higher level.

Limitations of the Review

There was a high degree of methodological heterogeneity amongst the included studies in terms of intervention format, practitioners’ features, assessment and study characteristics. An example of this heterogeneity can be seen in the duration of the interventions, as some were conducted over an hour whereas other were extended interventions over a period of a year. Additionally, we were unable to select high quality studies for this review to strengthen evidence due to their reduced availability (only 3 from 14 studies included in the meta-analysis could be considered a RCT). Regarding the measurement instruments, the major limitation was that most of them included only self-reported measures, which may have led to social desirability bias confirming the hypothesis of the study (Robins et al. 2007). We attempted to control the risk of bias of this unobserved heterogeneity by performing random effect analyses and meta-regressions with related moderators, such as the quality of the study as assessed with the QATQS, and study design type, if the number of studies allowed for it. However, the number of analyses undertaken was limited due to the small amount of studies available. For instance, we could not examine the effect of study design in two of our three main outcomes or explore differences between the practitioner’s professional backgrounds. In addition, few studies have collected follow-up data, which could have allowed us to investigate longer-term effects of the educational interventions. Therefore, research in this field requires RCTs with longer follow-ups in order to check effectivity and the real maintenance of educational effects of current interventions. At another level of analysis, we found it paradoxical that in the context of a reform that aims to give more prominence to service users, the latter hardly take part in the design, implementation and evaluation of these activities. Although it is true that some of the trainers and participants (peer-support workers) of these courses had lived experience of mental suffering, in the reviewed studies, the supposed beneficiaries of more horizontal interventions had mostly a passive role. In this sense, another limitation is that we did not included service users’ outcomes in the analysis due to the rare inclusion of these variables in educational evaluations. This is a significant limitation if we follow a recovery orientation, as the active involvement of users is a key factor of the recovery movement. Therefore, future systematic studies should assess the efficacy of this educational interventions on service-users’ outcomes.

Conclusions and Implications for Research

Recovery training activities seem to have a clear but moderate impact on the beliefs and attitudes of mental health professionals. Impact on practice is, however, not clear. Qualitative evidence seems to point in the direction of organisational obstacles preventing these changes. We believe that the use of mixed methods is essential to continue deepening into the possibilities that change can have on recovery training activities. Future studies should also consider the participation of service users, not only as trainers or peer-support workers, but by also involving the people who will receive the recovery interventions in the design and implementation of trials. Funding research agencies should also prioritise studies focusing on maintaining long-term changes by targeting organisational transformations and direct managerial support.

Availability of Data and Materials

The meta-analysis database from this project will be public under the same document object identifier as the article as supplemental material.

References

Ahmed, A. O., Serdarevic, M., Mabe, P. A., & Buckley, P. F. (2013). Triumphs and challenges of transforming a state psychiatric hospital in Georgia. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 15(2), 68–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623730.2013.820575.

Anthony, W. A. (1993). Recovery from mental illness: The guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal, 16(4), 11–23. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0095655.

Bachrach, L. L. (1993). The biopsychosocial legacy of deinstitutionalization. Psychiatric Services, 44(6), 523–546. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.44.6.523.

Basset, T. (2007). Psychosis revisited: A recovery-based workshop for mental health workers, service users and carers (2nd ed.). London: Pavilion.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., Kovacs, M., & Garrison, B. (1985). Hopelessness and eventual suicide: A 10-year prospective study of patients hospitalized with suicidal ideation. American Journal of Psychiatry, 142(5), 559–563. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.142.5.559.

Bedregal, L. E., O’Connell, M., & Davidson, L. (2006). The recovery knowledge inventory: Assessment of mental health staff knowledge and attitudes about recovery. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 30(2), 96–103. https://doi.org/10.2975/30.2006.96.103.

Begg, C. B., & Mazumdar, M. (1994). Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics, 50(4), 1088. https://doi.org/10.2307/2533446.

Bhanbhro, S., Gee, M., Cook, S., Marston, L., Lean, M., & Killaspy, H. (2016). Recovery-based staff training intervention within mental health rehabilitation units: a two-stage analysis using realistic evaluation principles and framework approach. BMC Psychiatry, 16(1), 292. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-0999-y.

Bird, V., Leamy, M., Boutillier, C. Le, Williams, J., & Slade, M. (2011). REFOCUS. Promoting recovery in community mental health services. London: Rethink.

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P., & Rothstein, H. R. (2009). Multiple outcomes or time-points within a study. In M. Borenstein, L. V. Hedges, J. P. Higgins, & H. R. Rothstein (Eds.), Introduction to meta-analysis (pp. 225–238). Chichester, UK: Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470743386.ch24.

Borkin, J. R., Steffen, J. J., Ensfield, L. B., Krzton, K., Wishnick, H., Wilder, K., et al. (2000). Recovery attitudes questionnaire: Development and evaluation. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 24(2), 95–102. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0095112.

Bracken, P., & Thomas, P. (2001). Postpsychiatry: a new direction for mental health. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 322(7288), 724–727. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.322.7288.724.

Byrne, L., Happell, B., Welch, T., & Moxham, L. J. (2013). “Things you can’t learn from books”: Teaching recovery from a lived experience perspective. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 22(3), 195–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0349.2012.00875.x.

Byrne, M. K., Sullivan, N. L., & Elsom, S. J. (2006). Clinician optimism: Development and psychometric analysis of a scale for mental health clinicians. The Australian Journal of Rehabilitation Counselling, 12(1), 11–20. https://doi.org/10.1375/jrc.12.1.11.

Caldwell, S., Liu, Y., Fedor, D. B., & Herold, D. M. (2009). Why are perceptions of change in the “Eye of the Beholder”? The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 45(3), 437–459. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886309336068.

Campbell, J., & Gallagher, R. (2007). A literature review and documentary analysis on recovery training in mental health practice. Glasgow: NHS Education for Scotland, AskClyde, Scottish Recovery Network.

Casper, E. S., Oursler, J., Schmidt, L. T., & Gill, K. J. (2002). Measuring practitioners’ beliefs, goals, and practices in psychiatric rehabilitation. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 25(3), 223–234. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0095020.

Chen, S.-P., Krupa, T., Lysaght, R., McCay, E., & Piat, M. (2013). The development of recovery competencies for in-patient mental health providers working with people with serious mental illness. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 40(2), 96–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-011-0380-x.

Chen, S.-P., Krupa, T., Lysaght, R., McCay, E., & Piat, M. (2014). Development of a recovery education program for inpatient mental health providers. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 37(4), 329–332. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000082.

Chinman, M. J., Young, A. S., Rowe, M., Forquer, S., Knight, E., & Miller, A. (2003). An instrument to assess competencies of providers treating severe mental illness. Mental Health Services Research, 5(2), 97–108. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023281527952.

Comstock, D. L., Hammer, T. R., Strentzsch, J., Cannon, K., Parsons, J., & Salazar, G., II. (2008). Relational-cultural theory: A framework for bridging relational, multicultural, and social justice competencies. Journal of Counseling & Development, 86(3), 279–287. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2008.tb00510.x.

Cook, J. A., Jonikas, J. A., & Razzano, L. (1995). A randomized evaluation of consumer versus nonconsumer training of state mental health service providers. Community Mental Health Journal, 31(3), 229–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02188749.

Cook, S., Mundy, T., Killaspy, H., Taylor, D., Freeman, L., Craig, T., et al. (2016). Development of a staff training intervention for inpatient mental health rehabilitation units to increase service users’ engagement in activities. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 79(3), 144–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308022615600175.

Copeland, M. E. (2002). Wellness recovery action plan. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 17(3–4), 127–150. https://doi.org/10.1300/J004v17n03_09.

Crowe, T. P., Deane, F. P., Oades, L. G., Caputi, P., & Morland, K. G. (2006). Effectiveness of a collaborative recovery training program in Australia in promoting positive views about recovery. Psychiatric Services, 57(10), 1497–1500. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.57.10.1497.

De Rijdt, C., Stes, A., van der Vleuten, C., & Dochy, F. (2013). Influencing variables and moderators of transfer of learning to the workplace within the area of staff development in higher education: Research review. Educational Research Review, 8, 48–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2012.05.007.

Deane, F. P., Goff, R. O., Pullman, J., Sommer, J., & Lim, P. (2018). Changes in mental health providers’ recovery attitudes and strengths model implementation following training and supervision. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9885-9.

Doughty, C., Tse, S., Duncan, N., & McIntyre, L. (2008). The wellness recovery action plan (WRAP): Workshop evaluation. Australasian Psychiatry, 16(6), 450–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/10398560802043705.

Eklund, M., Gunnarsson, A. B., Sandlund, M., & Leufstadius, C. (2014). Effectiveness of an intervention to improve day centre services for people with psychiatric disabilities. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 61(4), 268–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12120.

Enticott, J. C., Shawyer, F., Brophy, L., Russell, G., Fossey, E., Inder, B., … Meadows, G. (2016). The PULSAR primary care protocol: A stepped-wedge cluster randomized controlled trial to test a training intervention for general practitioners in recovery-oriented practice to optimize personal recovery in adult patients. BMC Psychiatry, 16(1), 451. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-1153-6

Felton, G. S., Wallach, H. F., & Gallo, C. L. (1974). Training mental health workers to better meet patient needs. Psychiatric Services, 25(5), 299–302. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.25.5.299.

Gabbidon, J., Clement, S., van Nieuwenhuizen, A., Kassam, A., Brohan, E., Norman, I., et al. (2013). Mental Illness: Clinicians’ attitudes (MICA) scale—psychometric properties of a version for healthcare students and professionals. Psychiatry Research, 206(1), 81–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2012.09.028.

Gee, M., Bhanbhro, S., Cook, S., & Killaspy, H. (2017). Rapid realist review of the evidence: Achieving lasting change when mental health rehabilitation staff undertake recovery-oriented training. Journal of Advanced Nursing. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13232.

Gilburt, H., Slade, M., Bird, V., Oduola, S., & Craig, T. K. J. (2013). Promoting recovery-oriented practice in mental health services: A quasi-experimental mixed-methods study. BMC Psychiatry, 13(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-167.

Goldman, H. H., & Morrissey, J. P. (1985). The alchemy of mental health policy: Homelessness and the fourth cycle of reform. American Journal of Public Health, 75(7), 727–731. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.75.7.727.

Goulet, M.-H., Larue, C., & Dumais, A. (2017). Evaluation of seclusion and restraint reduction programs in mental health: A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 31(6), 413–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2017.01.019.

Gronholm, P. C., Henderson, C., Deb, T., & Thornicroft, G. (2017). Interventions to reduce discrimination and stigma: The state of the art. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-017-1341-9.

Grusky, O., Tierney, K., & Spanish, M. T. (1989). Which community mental health services are most important? Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 17(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00710743.

Hansson, L., Jormfeldt, H., Svedberg, P., & Svensson, B. (2013). Mental health professionals’ attitudes towards people with mental illness: Do they differ from attitudes held by people with mental illness? International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 59(1), 48–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764011423176.

Hebson, G., & Cox, A. (2011). The gendered implications of corporate value change. Gender, Work and Organization, 18(2), 182–201. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2009.00509.x.

Henderson, C., Noblett, J., Parke, H., Clement, S., Caffrey, A., Gale-Grant, O., … Thornicroft, G. (2014). Mental health-related stigma in health care and mental health-care settings. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1(6), 467–482. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00023-6

Hervey, N. (1986). Advocacy or folly: the Alleged Lunatics’ Friend Society, 1845–63. Medical History, 30(3), 245–275. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025727300045701.

Higgins, A., Callaghan, P., deVries, J., Keogh, B., Morrissey, J., Nash, M., … Carter, T. (2012). Evaluation of mental health recovery and wellness recovery action planning education in Ireland: A mixed methods pre-postevaluation. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 68(11), 2418–2428. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05937.x

Higgins, J. P., & Green, S. (2011). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Chichester: Wiley.

Higgins, J. P., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J., & Altman, D. G. (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ, 327(7414), 557–560. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557.

Jackson-Blott, K., Hare, D., Davies, B., & Morgan, S. (2019). Recovery-oriented training programmes for mental health professionals: A narrative literature review. Mental Health & Prevention, 13, 113–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhp.2019.01.005.

Jacobson, N., & Curtis, L. (2000). Recovery as policy in mental health services: Strategies emerging from the states. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 23(4), 333–341. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0095146.

Kassam, A., Glozier, N., Leese, M., Henderson, C., & Thornicroft, G. (2010). Development and responsiveness of a scale to measure clinicians’ attitudes to people with mental illness (medical student version). Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 122(2), 153–161. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01562.x.

Killaspy, H., Cook, S., Mundy, T., Craig, T., Holloway, F., Leavey, G., … King, M. (2013). Study protocol: Cluster randomised controlled trial to assess the clinical and cost effectiveness of a staff training intervention in inpatient mental health rehabilitation units in increasing service users’ engagement in activities. BMC Psychiatry, 13(1), 216. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-216

Killaspy, H., King, M., Holloway, F., Craig, T. J., Cook, S., Mundy, T.,…, Bhanbhro, S. (2017). The rehabilitation effectiveness for activities for life (REAL) study: A national programme of research into NHS inpatient mental health rehabilitation services across England. Programme Grants for Applied Research, 5(7), 1–284. https://doi.org/10.3310/pgfar05070

Killaspy, H., Marston, L., Green, N., Harrison, I., Lean, M., Cook, S., … King, M. (2015). Clinical effectiveness of a staff training intervention in mental health inpatient rehabilitation units designed to increase patients’ engagement in activities (the rehabilitation effectiveness for activities for life [REAL] study): Single-blind, cluster-. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2(1), 38–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00050-9

Lamb, H. R. (1984). Deinstitutionalization and the homeless mentally ill. Hospital & Community Psychiatry, 35(9), 899–907. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.35.9.899.

Leamy, M., Clarke, E., Le Boutillier, C., Bird, V., Janosik, M., Sabas, K., … Slade, M. (2014). Implementing a complex intervention to support personal recovery: A qualitative study nested within a cluster randomised controlled trial. PLoS ONE, 9(5), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0097091

Lean, M., Leavey, G., Killaspy, H., Green, N., Harrison, I., Cook, S., … King, M. (2015). Barriers to the sustainability of an intervention designed to improve patient engagement within NHS mental health rehabilitation units: a qualitative study nested within a randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry, 15, 209. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0592-9

Mabe, P. A., Ahmed, A. O., Duncan, G. N., Fenley, G., & Buckley, P. F. (2014). Project GREAT: Immersing physicians and doctorally-trained psychologists in recovery-oriented care. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 45(5), 347–356. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037705.

Mabe, P. A., Rollock, M., & Duncan, G. N. (2016). Teaching clinicians the practice of recovery-oriented care. In N. N. Singh, J. W. Barber, & S. Van Sant (Eds.), Handbook of recovery in inpatient psychiatry (pp. 81–97). Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-40537-7_4.

Mancini, A. D. (2008). Self-determination theory: a framework for the recovery paradigm. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 14(5), 358–365. https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.bp.107.004036.

Mancini, A. D., & Finnerty, M. (2005). Recovery-oriented practices index (ROPI). New York: State Office of Mental Health.

Mansouri, M., & Lockyer, J. (2007). A meta-analysis of continuing medical education effectiveness. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 27(1), 6–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.88.

Meehan, T., & Glover, H. (2009). Using the recovery knowledge inventory (RKI) to assess the effectiveness of a consumer-led recovery training program for service providers. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 32(3), 223–226. https://doi.org/10.2975/32.3.2009.223.226.

Mittman, B. S. (2004). Creating the evidence base for quality improvement collaboratives. Annals of Internal Medicine, 140(11), 897. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-140-11-200406010-00011.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62(10), 1006–1012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005.

Mueser, K. T. (2006). The illness management and recovery program: Rationale, development, and preliminary findings. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 32(Supplement 1), S32–S43. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbl022.

National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools. (2008). Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies. Hamilton, ON: McMaster University.

Nilsson, I., Argentzell, E., Sandlund, M., Leufstadius, C., & Eklund, M. (2011). Measuring perceived meaningfulness in day centres for persons with mental illness. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 18(4), 312–320. https://doi.org/10.3109/11038128.2010.522592.

O’Connell, M., Tondora, J., Croog, G., Evans, A., & Davidson, L. (2005). From rhetoric to routine: Assessing perceptions of recovery-oriented practices in a state mental health and addiction system. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 28(4), 378–386. https://doi.org/10.2975/28.2005.378.386.

Oades, L., Deane, F., Crowe, T., Lambert, W. G., Kavanagh, D., & Lloyd, C. (2005). Collaborative recovery: an integrative model for working with individuals who experience chronic and recurring mental illness. Australasian Psychiatry, 13(3), 279–284. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1665.2005.02202.x.

Peebles, S. A., Mabe, P. A., Fenley, G., Buckley, P. F., Bruce, T. O., Narasimhan, M., … Williams, E. (2009). Immersing practitioners in the recovery model: An educational program evaluation. Community Mental Health Journal, 45(4), 239–245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-009-9212-9

Pollard, L., Gelbard, Y., Levy, G., & Gelkopf, M. (2008). Examining attitudes, beliefs and knowledge of effective practices in psychiatric rehabilitation in a hospital setting. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 32(2), 124–127. https://doi.org/10.2975/32.2.2008.124.127.

Ponce, A. N., Clayton, A., Gambino, M., & Rowe, M. (2016). Social and clinical dimensions of citizenship from the mental health-care provider perspective. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 39(2), 161–166. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000194.

R Core Team. (2018). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Recuperado de https://www.r-project.org/

Repique, R. J. R., Vernig, P. M., Lowe, J., Thompson, J. A., & Yap, T. L. (2016). Implementation of a recovery-oriented training program for psychiatric nurses in the inpatient setting: A mixed-methods hospital quality improvement study. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 30(6), 722–728. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2016.06.003.

Repper, J., & Breeze, J. (2007). User and carer involvement in the training and education of health professionals: A review of the literature. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 44(3), 511–519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.05.013.

Robins, R. W., Fraley, C. R., & Krueger, R. F. (2007). Handbook of research methods in personality psychology. New York: Guilford Publications.

Rose, N. S. (1989). Governing the soul: The shaping of the private self. New York: Taylor & Francis/Routledge.

Rundell, T. (2007). Perceptions of risky goals amongst people with schizophrenia and their support staff. (Postgraduate diploma). Central Queensland University.

Salgado, J. D., Deane, F. P., Crowe, T. P., & Oades, L. G. (2010). Hope and improvements in mental health service providers’ recovery attitudes following training. Journal of Mental Health, 19(3), 243–248. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638230903531126.

Salyers, M. P., Godfrey, J. L., McGuire, A. B., Gearhart, T., Rollins, A. L., & Boyle, C. (2009). Implementing the illness management and recovery program for consumers with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 60(4), 483–490. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2009.60.4.483.

Schuster, J.-P., Hoertel, N., & Limosin, F. (2011). The man behind Philippe Pinel: Jean-Baptiste Pussin (1746–1811)—psychiatry in pictures. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 198(3), 241–241. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.198.3.241a.

Schwarzer, G., Carpenter, J. R., & Rücker, G. (2015). Meta-analysis with R. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-21416-0.

Sedgwick, P., & Marston, L. (2013). Meta-analyses: standardised mean differences. BMJ, 347(dec06 1), f7257–f7257. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f7257.

Shawyer, F., Enticott, J. C., Brophy, L., Bruxner, A., Fossey, E., Inder, B., … Meadows, G. N. (2017). The PULSAR specialist care protocol: A stepped-wedge cluster randomized control trial of a training intervention for community mental health teams in recovery-oriented practice. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 172. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1321-3

Silverstein, S. M., & Bellack, A. S. (2008). A scientific agenda for the concept of recovery as it applies to schizophrenia. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(7), 1108–1124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2008.03.004.

Singh, N. N., Barber, J. W., & Van Sant, S. (2016). In: N. N. Singh, J. W. Barber, & S. Van Sant, (Eds.), Handbook of recovery in inpatient psychiatry. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-40537-7

Slade, M., Amering, M., Farkas, M., Hamilton, B., O’Hagan, M., Panther, G., … Whitley, R. (2014). Uses and abuses of recovery: Implementing recovery-oriented practices in mental health systems. World Psychiatry, 13(1), 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20084

Slade, M., Bird, V., Clarke, E., Le Boutillier, C., McCrone, P., Macpherson, R., … Leamy, M. (2015). Supporting recovery in patients with psychosis through care by community-based adult mental health teams (REFOCUS): A multisite, cluster, randomised, controlled trial. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2(6), 503–514. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00086-3

Snyder, C. R., Sympson, S. C., Ybasco, F. C., Borders, T. F., Babyak, M. A., & Higgins, R. L. (1996). Development and validation of the State Hope Scale. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(2), 321–335. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.2.321.

Strating, M. M. H., Broer, T., van Rooijen, S., Bal, R. A., & Nieboer, A. P. (2012). Quality improvement in long-term mental health: results from four collaboratives. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 19(5), 379–388. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01802.x.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2012). SAMHSA’ s working definition of recovery.

Sweeney, P. D., & Mcfarlin, D. B. (1997). Process and outcome: Gender differences in the assessment of justice. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 18(1), 83–98. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(199701)18:1%3c83:AID-JOB779%3e3.0.CO;2-3.

Tsai, J., Salyers, M. P., & Lobb, A. L. (2010). Recovery-oriented training and staff attitudes over time in two state hospitals. Psychiatric Quarterly, 81(4), 335–347. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-010-9142-2.

Tsai, J., Salyers, M. P., & McGuire, A. B. (2011). A cross-sectional study of recovery training and staff attitudes in four community mental health centers. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 34(3), 186–193. https://doi.org/10.2975/34.3.2011.186.193.

Way, B. B., Stone, B., Schwager, M., Wagoner, D., & Bassman, R. (2002). Effectiveness of the New York State office of mental health core curriculum: Direct care staff training. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 25(4), 398–402. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0094997.

Williams, V., Deane, F. P., Oades, L. G., Crowe, T. P., Ciarrochi, J., & Andresen, R. (2016). A cluster-randomised controlled trial of values-based training to promote autonomously held recovery values in mental health workers. Implementation Science, 11(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0363-5.

Wilrycx, G., Croon, M. A., van den Broek, A. H. S., & van Nieuwenhuizen, C. (2012). Mental health recovery: Evaluation of a recovery-oriented training program. The Scientific World Journal, 2012, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1100/2012/820846.

Young, A. S., Chinman, M., Forquer, S. L., Knight, E. L., Vogel, H., Miller, A., … Mintz, J. (2005). Use of a consumer-led intervention to improve provider competencies. Psychiatric Services, 56(8), 967–975. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.56.8.967

Zuaboni, G., Hahn, S., Wolfensberger, P., Schwarze, T., & Richter, D. (2017). Impact of a mental health nursing training-programme on the perceived recovery-orientation of patients and nurses on acute psychiatric wards: Results of a pilot study. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 38(11), 907–914. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2017.1359350.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all people and organisations involved in the cultural change that the Recovery in mental health movement involves.

Funding

FJEO has received funding from the European Union’s Framework Programme for Research and Innovation Horizon 2020 (2014–2020) under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Grant Agreement No 654808. HGM is supported by a predoctoral contract (FPU15/01721) given by the Spanish Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports. None of these agencies had any role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FJEO designed the study, wrote the protocol, conducted literature searches and provided summaries of research studies. HGM extracted data from individual studies to carry the meta-analytic calculations. Both authors assessed risk of bias in individual studies. Author FJEO conducted the statistical analysis. FJEO wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Both authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to the present study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Eiroa-Orosa, F.J., García-Mieres, H. A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Recovery Educational Interventions for Mental Health Professionals. Adm Policy Ment Health 46, 724–752 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-019-00956-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-019-00956-9