Abstract

Adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) among HIV-infected individuals is necessary to both individual and public health, and psychosocial problems have independently been associated with poor adherence. To date, studies have not systematically examined the effect of multiple, co-occurring psychosocial problems (i.e., “syndemics”) on ART adherence. Participants included 333 HIV-infected individuals who completed a comprehensive baseline evaluation, as part of a clinical trial to evaluate an intervention to treat depression and optimize medication adherence. Participants completed self-report questionnaires, and trained clinicians completed semi-structured diagnostic interviews. ART non-adherence was objectively measured via an electronic pill cap (i.e., MEMS). As individuals reported a greater number of syndemic indicators, their odds of non-adherence increased. Co-occurring psychosocial problems have an additive effect on the risk for poor ART adherence. Future behavioral medicine interventions are needed that address these problems comprehensively, and/or the core mechanisms that they share.

Resumen

Entre las personas VIH-positivas, adherencia a los tratamientos antirretrovirales (ART por sus siglas en inglés) es clave para la salud personal y la salud pública. Problemas psicosociales han sido independientemente asociados con un bajo nivel de adherencia. Estudios científicos aun no han examinado el impacto en la adherencia al ART dentro del contexto de coocurrencia de varios problemas psicosociales (“syndemics”). Personas VIH-positivas (N = 333) completaron una evaluación de línea base, como parte de su participación en un ensayo clínico donde el propósito fue examinar una intervención para el tratamiento de la depresión y mejoramiento de adherencia a los medicamentos. Los participantes completaron un autoinforme y también una entrevista diagnóstica semiestructurada. El nivel de adherencia al ART fue medido a través de un tapón de botella electrónica (sistema MEMS). Con cada indicador de “syndemics” que fue reportado por los participantes, sus probabilidades de no adhesión aumentaron. La coocurrencia de varios problemas psicosociales resultan en un impacto aditivo al riesgo de tener pobre adherencia al ART. Para enfrentar estos problemas de manera integral se necesita el desarrollo de intervenciones basadas en la medicina conductual y mejorar el entendimiento de los mecanismos fundamentales los cuales tienen en común.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Optimal levels of adherence are necessary to achieve the maximal benefits of antiretroviral therapy for HIV. Among individual characteristics related to adherence, psychosocial problems such as mental health, lifestyle behaviors, and stressful life events have frequently been cited as barriers to adherence [1]. Of these factors, depression is one of the most common comorbidities of HIV [2] and is consistently associated with poor rates of ART adherence [3]. Similarly, alcohol abuse and other substance use have been linked to lower rates of ART adherence [4, 5]. Finally, individuals with a history of traumatic or stressful life events also report poor adherence [1, 6].

“Syndemic” is a term used to describe the constellation of multiple risk factors which interact synergistically and lead to notable increases in disease burden, and has been applied to HIV sexual transmission over the past decade [7, 8]. Several studies have indicated that a number of co-occurring psychosocial syndemic factors, in particular depression, childhood sexual abuse, intimate partner violence, and polysubstance use, increase risk for contracting HIV [5, 8] through links to higher rates of condomless sex [9, 10]. Although recent adherence treatment guidelines have also highlighted the need for addressing additional syndemic factors among HIV-infected adults [11], to our knowledge, no studies have examined the relationship between multiple psychosocial syndemic factors and ART adherence. Approaching adherence through the lens of syndemic theory may lead to a better understanding of how such factors interact and how their confluence results in decreased adherence. A greater understanding of this interplay may lead to the development of tailored interventions to increase adherence among HIV-infected individuals. To this end, the current study aimed to examine the distribution of psychosocial syndemic factors among HIV-infected adults and the relationship between these syndemic factors and objectively measured ART adherence. We hypothesized that as the number of syndemic indicators increase, the odds of ART non-adherence will also increase.

Methods

Participants

The current study utilized baseline data for patients being screened for participation in a randomized controlled efficacy trial investigating the use of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for treating depression and enhancing ART adherence in HIV-infected adults. Enrollment occurred between February 2009 and May 2012. Participants completed an initial telephone screener and were eligible to participate in the baseline visit if they endorsed the following: 18 years of age or older; connected to an HIV medical provider; prescribed ART for at least 2 months; and screened positive for depressive symptoms on a 2-item measure assessing symptoms over the prior 2 weeks (PHQ-2) [12]. Participants received $50.00 compensation for completing the baseline screening visit. Participants in the current sample included 333 HIV-infected adult men and women. Sample characteristics are portrayed in Table 1.

Procedure

Participants were recruited through three HIV primary care clinics in southern New England, as well as through community outreach. All participants received a complete description of the study and provided written informed consent, and all study procedures were approved by the IRBs at the respective study sites. Data for the current study were taken from the initial baseline visit, which included clinician-administered interviews and self-report questionnaires that were used to establish eligibility. Participants were also given an electronic pill cap (MEMS; Medication Event Monitoring System; AARDEX) at baseline to monitor their adherence to ART. MEMS data was measured from the baseline visit to the following visit, typically conducted 2 weeks later, when participants were informed of their eligibility to participate in the study.

Measures

ART Non-Adherence. Participants were assigned a MEMS cap to use with the antiretroviral medication they either were prescribed to take most frequently or reported having the most difficulty remembering to take. The MEMS cap recorded each time the bottle was opened; however, to account for doses that participants may have taken without using the bottle (e.g., if participants opened the bottle in the morning with the intent of taking the medication in the afternoon), to increase the validity of this assessment, doses were also counted as taken if participants could recount specific times in which they took their medication but did not use the pill cap [13–15]. As per our prior work, a dose was counted as missed if it was not taken within ±2 h of a previously designated target time [16–18]. This follows, as dose timing adherence is much more robustly predictive of attaining undetectable viral load compared to simple daily adherence [19]. Given that newer forms of ART are somewhat more forgiving to non-adherence than earlier regimens [20], and that less than 80 % adherence to these newer forms of ART is associated with a high risk for virologic rebound [21], a dichotomous variable of non-adherence was created based on adherence levels below 80 % coded as “1” and those at or above 80 % as “0.”

Syndemics

Identification of psychosocial syndemics (i.e., childhood abuse, current violence, alcohol or substance abuse/dependence, post-traumatic stress disorder, anti-social personality disorder, anxiety spectrum disorders, mood disorders, and psychotic disorders) were assessed via clinician-administered interviews and self-report questionnaires using previously validated instruments (see below). If a participant endorsed experiencing or engaging in a given syndemic indicator, it was coded 1, and if not, it was coded 0. The presence of psychological disorders was assessed via the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) for DSM-IV, which is one of the most widely used diagnostic instruments to reliably determine Axis I psychiatric disorders in clinical populations [22–25]. Childhood abuse was assessed with the Physical and Sexual Abuse Questionnaire, which is a questionnaire based upon a standardized interview developed for application in HIV-infected patients [26]. Current violence was assessed via one item (“In the past 6 months were you physically attacked or sexually abused or assaulted or had your life threatened?”) from the stressful life events scale (LES-Brief-Revised) [26]. The number of syndemic factors ranged from 0 to 8, and for the purposes of the current study the following syndemic categories were created: “0”, “1 or 2”, “3 or 4”, and “5 or more”. In the Stall et al. seminal paper [8], syndemic conditions were broken-down into “0”, “1”, “2”, and “3 or 4.” We modeled our approach on this paper, but given that we had 8 possible syndemic indicators, compared to 4 in the Stall et al. paper, we slightly adjusted our categories to “0”, “1–2”, “3–4” and “5+”. Had we continued to break groups down even further, we would have been left with cells containing relatively few participants.

Statistical Analyses

The primary analysis utilized binary logistic regression, with the dichotomous ART non-adherence variable entered as the dependent variable. The categorical syndemic variable was entered as the independent variable, with “0” set as the referent group. Overall model fit was assessed with a χ 2 test, with significance denoting good fit. Potential covariates (e.g., age, sex, race, ethnicity) were examined for possible inclusion in the model; however, neither the outcome nor the predictor variables significantly differed on these variables. Further, sensitivity analyses revealed that the model did not significantly change when adding these variables into the model; thus, the results presented below are unadjusted for additional covariates.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

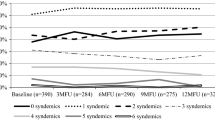

Approximately half (56 %) of the sample (n = 191) could be categorized as non-adherent via our 80 % cutoff. With respect to the number of syndemics, the groups were unequally distributed, with 10 (3 %), 110 (33 %), 135 (41 %), and 78 (23 %) participants in the “0”, “1–2”, “3–4” and “5+” categories, respectively.

Primary Analyses

Results from the logistic regression analysis revealed that the overall model was significant, χ 2(3) = 11.26, p = .01, indicating the model fit the data well, and examination of the odds ratios suggests that the odds of non-adherence increased in relation to the number of syndemic indicators. Specifically, those with “1–2” syndemics had 4.1 times greater odds (95 % CI: .84, 20.4, p = .08) than those with “0” to be categorized as non-adherent. Those with “3–4” had 5.0 times greater odds (95 % CI: 1.02, 24.4, p = .047) of being categorized as non-adherent than those with “0.” Those with “5+” had 8.5 times greater odds of being categorized as non-adherent (95 % CI: 1.7, 42.9, p = .01) (Fig. 1).

Discussion

The current study was the first, to our knowledge, that tested a syndemics model as it relates to ART adherence among HIV-infected individuals. Our findings were consistent with syndemic theory, in that participants who endorsed a greater number of psychosocial syndemic factors were at increasing odds of reporting suboptimal ART adherence. These findings have implications for both the management of HIV-infected individuals and their personal health, as well as public health implications.

Although the current study examined one aspect of HIV care, ART adherence, the results may also have implications for other points of intervention along the continuum of HIV testing and treatment. For instance, only 25 % of individuals living with HIV in the U.S. are virally suppressed [27]. Extant data show that roughly half of individuals living with HIV, who are in care, screen positive for at least one psychiatric disorder, with 40 % reporting use of illicit substances [2]. Thus, it would seem plausible that individuals who are not connected with HIV care may experience even higher levels of psychopathology. This theoretically higher level of psychological and substance use problems may also serve as barriers to initiate and maintain contact with HIV care. Consequently, syndemic models may also wish to be incorporated along the continuum of HIV care, and not only focus on ART adherence.

The current study is not without limitations. Of note, the cross-sectional design precludes temporal inference. Future studies may wish to assess the relationship between syndemics and ART non-adherence with multiple waves of data, to more accurately model this association. The current study also focused on psychosocial syndemics; however, additional syndemic indicators, such as poverty, homelessness and incarceration, are likely to impair optimal adherence. Additionally, our referent group, “0”, included only 10 participants. A group with a small n will be associated with inflated standard errors; however, the small n in the referent group would reduce power to detect significant differences, which was not the case in the present study. Also, previous syndemics research has separated those with 1 versus 2 syndemic conditions [8]; however, in the current study, we combined these categories, as we had many more potential syndemic conditions (i.e., 8), than prior studies assessed. Future research may wish to replicate these findings with samples outside the context of a depression trial, with aims of culling a larger group of individuals with no psychosocial syndemic indicators. Lastly, although the current study did not have a large enough sample to explore unique patterns of syndemic indicators and their relation to ART adherence, recent longitudinal data have found patterns that include depression and stimulant use among those most risky for HIV seroconversion [28]. However, we are unaware of any similar work addressing risk for ART non-adherence, and this would be a fruitful area of future research.

The results from the current study have the potential to inform clinical practice. Not only are individual psychosocial syndemic indicators predictive of poor ART adherence, but as these psychosocial problems are combined, the risk for suboptimal adherence also increases precipitously. Interventions that address ART adherence within the context of psychosocial distress may prove to increase adherence and decreases distress and impairment. One such intervention, CBT for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) [17, 18, 29] has shown efficacy compared to enhanced standard of care in the treatment of poor adherence and depression for HIV-infected individuals. However, given that additional psychosocial stressors beyond depression also lead to poor adherence, and their confluence leads to exaggerated adverse outcomes, interventions that address core pathological processes that underlie various syndemic indicators may prove to be an effective and efficient approach. For instance, the unified protocol [30–32] has recently been promoted as an efficient and effective approach to treating pathological mechanisms (e.g., maladaptive thinking, behavioral avoidance, poor distress tolerance) that are shared across anxiety and mood disorders. A similar approach to addressing psychosocial syndemic indicators may also be an effective strategy when working with individuals living with HIV, to improve their psychological well-being and engagement in care-related behaviors that will enhance personal and public health, through ART adherence.

In conclusion, as the number of psychosocial syndemic indicators increase, so does the risk for ART non-adherence. Poor adherence is associated with individual morbidity and mortality, and recent landmark studies have also highlighted the salience of optimal adherence for reducing viral load and subsequent risk for transmitting HIV. Thus, integrative cognitive-behavioral interventions that address adherence in the context of intertwined psychosocial syndemics are worthy of additional attention.

References

Blashill AJ, Perry N, Safren SA. Mental health: a focus on stress, coping, and mental illness as it relates to treatment retention, adherence, and other health outcomes. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2011;8:215–22.

Bing EG, Burnam MA, Longshore D, Fleishman JA, Sherbourne CD, London AS, et al. Psychiatric disorders and drug use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:721–8.

Gonzalez JS, Batchelder AW, Psaros C, Safren SA. Depression and HIV/AIDS treatment nonadherence: a review and meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;58:181–7.

Gonzalez A, Barinas J, O’Cleirigh C. Substance use: impact on adherence and HIV medical treatment. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2011;8:223–34.

Parsons JT, Rosof E, Mustanski B. The temporal relationship between alcohol consumption and HIV-medication adherence: a multilevel model of direct and moderating effects. Health Psychol. 2008;27:628–37.

Mugavero MJ, Raper JL, Reif S, Whetten K, Leserman J, Thielman NM, et al. Overload: impact of incident stressful events on antiretroviral medication adherence and virologic failure in a longitudinal, multisite human immunodeficiency virus cohort study. Psychosom Med. 2009;71:920–6.

Singer M, Clair S. Syndemics and public health: reconceptualizing disease in bio-social context. Med Anthropol Q. 2003;17:423–41.

Stall R, Mills TC, Williamson J, Hart T, Greenwood G, Paul J, et al. Association of co-occurring psychosocial health problems and increased vulnerability to HIV/AIDS among urban men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:939–42.

Safren SA, Blashill AJ, O’Cleirigh CM. Promoting the sexual health of MSM in the context of comorbid mental health problems. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(Suppl 1):S30–4.

Safren SA, Reisner SL, Herrick A, Mimiaga MJ, Stall RD. Mental health and HIV risk in men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55(Suppl 2):S74–7.

Thompson MA, Mugavero MJ, Amico KR, Cargill VA, Chang LW, Gross R, et al. Guidelines for improving entry into and retention in care and antiretroviral adherence for persons with HIV: evidence-based recommendations from an International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care panel. Ann. Intern. Med. 2012;156:817–833, W–284, W–285, W–286, W–287, W–288, W–289, W–290, W–291, W–292, W–293, W–294.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13.

Liu H, Golin CE, Miller LG, Hays RD, Beck CK, Sanandaji S, et al. A comparison study of multiple measures of adherence to HIV protease inhibitors. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:968–77.

Liu H, Miller LG, Hays RD, Wagner G, Golin CE, Hu W, et al. A practical method to calibrate self-reported adherence to antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43(Suppl 1):S104–12.

Llabre MM, Weaver KE, Durán RE, Antoni MH, McPherson-Baker S, Schneiderman N. A measurement model of medication adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy and its relation to viral load in HIV-positive adults. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2006;20:701–11.

Applebaum AJ, Reilly LC, Gonzalez JS, Richardson MA, Leveroni CL, Safren SA. The impact of neuropsychological functioning on adherence to HAART in HIV-infected substance abuse patients. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23:455–62.

Safren SA, O’Cleirigh C, Tan JY, Raminani SR, Reilly LC, Otto MW, et al. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) in HIV-infected individuals. Health Psychol. 2009;28:1–10.

Safren SA, O’Cleirigh CM, Bullis JR, Otto MW, Stein MD, Pollack MH. Cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) in HIV-infected injection drug users: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80:404–15.

Gill CJ, Sabin LL, Hamer DH, Keyi X, Jianbo Z, Li T, et al. Importance of dose timing to achieving undetectable viral loads. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:785–93.

Bangsberg DR. Less than 95 % adherence to nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor therapy can lead to viral suppression. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:939–41.

Parienti J-J, Das-Douglas M, Massari V, Guzman D, Deeks SG, Verdon R, et al. Not all missed doses are the same: sustained NNRTI treatment interruptions predict HIV rebound at low-to-moderate adherence levels. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2783.

Amorim P, Lecrubier Y, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Sheehan D. DSM-IH-R psychotic disorders: procedural validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). Concordance and causes for discordance with the CIDI. Eur Psychiatry. 1998;13:26–34.

Lecrubier Y, Sheehan D, Weiller E, Amonrim P, Bonora I, Harnett Sheehan K, et al. The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). A short diagnostic structured interview: reliability and validity according to the CIDI. Eur Psychiatry. 1997;12:224–31.

Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33 quiz 34–57.

Sheehan D, Lecrubier Y, Harnett Sheehan K, Janavs J, Weiller E, Keskiner A, et al. The validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) according to the SCID-P and its reliability. Eur Psychiatry. 1997;12:232–41.

Leserman J, Li Z, Drossman DA, Toomey TC, Nachman G, Glogau L. Impact of sexual and physical abuse dimensions on health status: development of an abuse severity measure. Psychosom Med. 1997;59:152–60.

Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, Del Rio C, Burman WJ. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:793–800.

Mimiaga M, O’Cleirigh C, Biello K, Robertson A, Safren S, Coates T, et al. The effect of psychosocial syndemic production on 4-year HIV incidence and risk behavior ain a large cohort of sexually active men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. (in press).

Nafisseh Soroudi GKP. CBT for medication adherence and depression (CBT-AD) in HIV-infected patients receiving methadone maintenance therapy. Cogn Behav Pract. 2008;15(1):93–106.

Allen LB, McHugh RK, Barlow DH. Emotional disorders: a unified protocol. In: Barlow DH, editor. Clinical handbook of psychological disorders. 4th ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. p. 216–49.

Barlow DH. Anxiety and its disorders: the nature and treatment of anxiety and panic (2nd edition). New York: Guilford Press; 2004.

Farchione TJ, Fairholme CP, Ellard KK, Boisseau CL, Thompson-Hollands J, Carl JR, et al. Unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: a randomized controlled trial. Behav Ther. 2012;43:666–78.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health, Grant R01MH084757, awarded to Dr. Steven A. Safren, NIMH K24MH094214 awarded to Dr. Safren, and NIMH K23MH096647 awarded to Dr. Aaron Blashill. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Blashill, A.J., Bedoya, C.A., Mayer, K.H. et al. Psychosocial Syndemics are Additively Associated with Worse ART Adherence in HIV-Infected Individuals. AIDS Behav 19, 981–986 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-014-0925-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-014-0925-6