Abstract

Virtual patients are increasingly used in undergraduate psychiatry education. This article reports on a systematic review aimed at providing an overview of different approaches in this context, describing their effectiveness, and thematically comparing learning outcomes across different undergraduate programs. The authors searched PubMed, PsycInfo, CINAHL, and Scopus databases for articles published between 2000 and January 2021. Quantitative and qualitative studies that reported on outcomes related to learners’ knowledge, skills, and attitudes following an intervention with virtual patients in undergraduate psychiatry education were reviewed. Outcomes were thematically compared, and a narrative synthesis of the different outcomes and effectiveness was provided. Of 7856 records identified, 240 articles were retrieved for full-text review and 46 articles met all inclusion criteria. There were four broad types of virtual patient interventions: case-based presentation (n = 17), interactive virtual patient scenarios (n = 14), standardized virtual patients (n = 10), and virtual patient videogames (n = 5). The thematic analysis revealed that virtual patients in psychiatry education have been used for learners to construe knowledge about symptomatology and psychopathology, develop interpersonal and clinical communicative skills, and to increase self-efficacy and decrease stigmatizing attitudes towards psychiatric patients. In comparison with no intervention, traditional teaching, and text-based interventions, virtual patients were associated with higher learning outcomes. However, the results did not indicate any superiority of virtual patients over non-technological simulation. Virtual patients in psychiatry education offer opportunities for students from different health disciplines to build knowledge, practice skills, and improve their attitudes towards individuals with mental illness. The article discusses methodological shortcomings in the reviewed literature. Future interventions should consider the mediating effects of the quality of the learning environment, psychological safety, and level of authenticity of the simulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Psychiatry education is an important element in the health professions (Lipari et al., 2013; Patel et al., 2016). Simulation-based education includes interaction with real or virtual objects, devices, or persons, and represents a promising learning tool in psychiatry. In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, Piot et al. (2020) demonstrated the effectiveness of simulation-based psychiatry education for developing knowledge, skills, and attitudes of medical students, postgraduate medical trainees, and qualified doctors. Furthermore, narrative reviews have suggested that simulation-based psychiatry education can increase students’ level of knowledge, communication skills, empathy, and engagement (Abdool et al., 2017; Brown, 2008; Kunst et al., 2017; McNaughton et al., 2008; Øgård-Repål et al., 2018; Vandyk et al., 2018). However, differences in assessment and simulation methodologies made direct comparison difficult. In addition, these studies predominantly focused on face-to-face simulation, including role-play, mannequins, and using standardized or simulated patients. Such methodologies are costly, resource-intensive for staff, challenging to schedule when used in larger student cohorts, and the number of learners accommodated at any given time is limited (Triola et al., 2006). Moreover, simulation experiences may not be standardized and there is often little opportunity for repetitive practice (Andreatta et al., 2010).

Virtual patient simulations may ameliorate some of these shortcomings (Peddle et al., 2019). In this review, we define virtual patients as interactive, screen-based, and dynamic patient cases that simulate real-life clinical scenarios. Virtual patient simulations can be delivered to a large number of students and provide access to situations where actual clinical encounters are difficult to facilitate (Kononowicz et al., 2019). In online and distance learning environments, virtual patients can also be adapted to the needs of individual learners and teachers.

While virtual patients have been researched and used in medical education as a whole (Cook & Triola, 2009; Cook et al., 2010; Kononowicz et al., 2015, 2019), they are a relatively new approach in psychiatry education (Brown, 2008; Guise et al., 2012). To the best of our knowledge, there has been no systematic review of the use of virtual patients in health disciplines offering undergraduate psychiatry education. In this systematic review, we evaluate empirical literature on virtual patients used as educational interventions in undergraduate psychiatry education to develop students’ knowledge, skills, and attitudes. The aims of the current review were to:

-

1.

Provide an overview of the most used approaches to date and describe their effectiveness.

-

2.

Examine and thematically compare learning outcomes across different undergraduate programs.

Methods

Design

The study was preregistered at Prospero (CRD42020196046) as a systematic review and was reported in adherence with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses guideline (Moher et al., 2009). The study was exempt from ethical approval as it was a literature study that did not directly involve human subjects.

Eligibility

We considered all studies on educational interventions using interactive, screen-based, and dynamic virtual patients in the context of undergraduate psychiatry education. Inclusion criteria also included studies reporting on outcomes related to the students’ knowledge, skills, and/or attitudes. We excluded studies that did not meet these criteria, e.g., studies examining virtual patient interventions with static multimedia representations or interventions not developed with an educational purpose. Other exclusion criteria were studies reporting on outcomes with no relevance to the educational effect of the intervention, e.g., outcomes related to satisfaction, and studies that were published in languages different from English, not peer-reviewed, or strictly descriptive studies (see full inclusion and exclusion criteria in the Online Resource 1).

Search methods for identification of studies

PubMed, PsycInfo, CINAHL, and Scopus databases were searched in January 2021. The search terms included Medical Subject Headings and free-text words that referred to (1) virtual patients, (2) undergraduate education, and (3) mental illness, separated by Boolean operators (see Online Resource 2). Free-text words were limited to titles and abstracts, and the search was limited to publications from the Year 2000 onward.

Study selection

Search results were retrieved and imported into the Endnote (version 9). The first and last authors independently reviewed and screened titles and abstracts, and eligible studies were included for full-text screening using Covidence systematic review software (Innovation, 2020). The same reviewers independently screened the studies for eligibility and final inclusion. Disagreements were resolved by discussion and inclusion of the second co-author.

Data items for extraction

The data extraction template was developed through iterative testing and revision. Studies were classified as using quantitative, mixed, or qualitative methods. The quantitative and mixed-methods studies were further classified as no-intervention controlled (single-group pretest–posttest comparison, or comparison with another group receiving no intervention), non-media-comparative (comparison with a group receiving a non-media-based educational intervention, e.g., a face-to-face simulation), or media-assisted learning comparative (comparison with a group receiving a media-based educational technology, including an alternate virtual patient). For studies with more than one comparison condition, we classified the study according to the most active control. We abstracted information on:

-

1.

The characteristics of study participants (field of study; year of study; country where the study was conducted and its World Bank income category).

-

2.

Type of learning outcome (knowledge, skills, and/or attitudes).

-

3.

Methods used to measure the learning outcomes (subjective/objective, validated/non-validated).

-

4.

The type of virtual patient was synthesized in a narrative description. We coded the type of case progression as linear (the virtual patient followed the same course regardless of decisions), branched (the virtual patient evolved with participants’ decisions affecting subsequent events), or unclear. We coded the virtual patient’s use as self-directed or teacher assisted, and whether the students carried out the intervention as an individual or group assignment. We also abstracted information on the virtual patient clinical topic, the number of cases, and the clinical variation.

Finally, we abstracted information on the presence of features of effective simulations identified in a previous review of virtual patient simulation (Cook & Triola, 2009):

-

Feedback provided to the learner (coded as low, moderate, or high).

-

Opportunity for repetitive practice (present or absent).

-

Curriculum integration (the virtual patient was an integrated part of the curriculum/course [present] or an optional activity [absent]).

Data synthesis and analysis

The data extraction structure allowed the succinct organization of the data to compare and incorporate findings from a variety of research methods (Stubbings et al., 2012). A narrative synthesis was performed to synthesize the findings systematically. We decided a priori to forego meta-analyses because of the research questions and because we expected variety in study populations, interventions, and educational outcomes.

Data related to the type of virtual patient was categorized following the framework for virtual patient classifications originally proposed by Talbot et al. (2012) and modified by Kononowicz et al. (2015).

Data related to the type of learning outcomes were compared using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Emerging themes related to each of the main categories were identified and confirmed with primary sources.

Quality assessment

To assess the quality of the selected studies, we employed two tools: The Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument (MERSQI) (Cook & Reed, 2015) for quantitative and mixed-methods studies and the QualSyst standard assessment criteria (Kmet, 2004) for qualitative studies.

The MERSQI is a validated tool designed to measure the quality of medical education research with varied quantitative methodologies, including ten items in six domains (study design, sampling, type of data, validation of evaluation instrument, data analysis, outcomes measured). MERSQI scores range from 5 (indicating lowest quality) to 18 (indicating highest quality). The first author served as the gold standard rater and assessed the quality of all included quantitative studies, and the last author assessed 24% of these as a quality check, with intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) = 0.81.

The QualSyst assessment covers a variety of qualitative study designs and consists of a checklist for qualitative studies with ten criteria with scores. The total score ranges from 0 (lowest quality) to 1 (highest quality) and rests on the ratio of the total score earned to the total possible score. The first and last authors assessed the quality of all included qualitative and mixed-method studies, and disagreements were resolved in discussion, ICC = 0.69.

Results

Trial flow

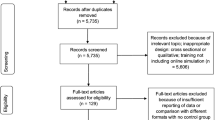

A total of 7856 records were identified. After removal of duplicates and exclusion of irrelevant references, 240 studies remained for full-text screening. Of these, 46 studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria (see flowchart in Fig. 1).

Quality assessment

The mean MERSQI score of the quantitative studies was 11.94 (range 7 – 14.5), which is comparable to other research adopting the MERSQI (Cook & Reed, 2015). The QualSyst score of the qualitative studies was 0.91, which can be interpreted as indicative of high quality based on the criteria required for scores of over 0.80 in the literature (Balaguer et al. 2020; Speyer et al., 2018). The mixed-methods studies received scores of 11.78 on the MERSQI and 0.61 on the QualSyst. See Online Resource 3.

Study and participant characteristics

We identified five studies that used rigorous qualitative methods and 41 studies that used quantitative or mixed-methods comparative designs (see Table 1).

Of the 41 quantitative and mixed-methods comparative studies, 17 (41%) studies reported comparison with no intervention including two RCTs, 11 (27%) studies reported on non-media-comparison including three RCTs, and 13 (32%) studies reported results on a media-assisted learning comparative including eight RCTs. One study was conducted in a low-middle-income country, India (Nongmeikapam et al., 2019), while the remaining 45 studies were conducted in high-income countries. Sample sizes of the studies varied from n = 6 (Washburn et al., 2016) to n = 532 (Kelly et al., 2020). A total of 5563 students participated in the studies, including 2546 medical students, 1873 nursing students, 254 psychology students, 28 social work students, 87 students who were enrolled in a psychology course or a social work course, 244 pharmacy students, and 531 students enrolled in a healthcare-related education (see Online Resource 3).

Virtual patient characteristics and educational characteristics

The reviewed studies included different descriptors for the type of intervention, e.g., “virtual patient”, “video-based teaching”, “computerized clinical simulation”. Following Talbot et al. (2012), we categorized the virtual patient in each intervention as being either a case-based presentation of a virtual patient (n = 17), an interactive virtual patient scenarios (n = 14), a standardized virtual patients (n = 10), and a virtual patient videogames (n = 5). This is shown in the Online Resource 4 together data on how the studies used different means to portray the patient, i.e., actors, avatars and animations, or real patients.

Geriatric psychiatry was the the most widely represented topic (Buijs-Spanjers et al., 2018, 2019, 2020; Chao et al., 2012; Goldman et al., 2008; Kelly et al., 2020; Matsumura et al., 2018; Robles et al., 2019; Rosen et al., 2013). Other topics included managing boundary-seeking patients (Kunaparaju et al., 2018; Taverner et al. 2000), assessing the risk of interpersonal violence (Verkuyl et al., 2017), combating stigma (Kerby et al., 2008; Wei Liu, 2021; Nguyen et al., 2012; Winkler et al., 2017), screening for suicidal ideation (Foster et al., 2015; Kullberg et al., 2020) and substance use disorders (Bremner et al., 2020; Burmester et al., 2019; Koetting & Freed, 2017; Lee et al., 2008; Tanner et al., 2012), assessment (Washburn et al., 2016, 2020), mental state examination (Fog-Petersen et al., 2020; Hansen et al., 2020; Martin, et al. 2020; ; Williams et al., 2001), diagnostic skills (Gutiérrez-Maldonado et al., 2015), treatment of mental illness (Hayes-Roth, 2004; Kitay et al., 2020; Mastroleo et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2020; Warnell et al., 2005), patient-centered skills (Chen et al., 2018; Choi et al., 2020; Foster et al., 2016; Pedersen et al., 2018, 2019; Sunnqvist et al., 2016), behavioral medicine (Berman et al., 2017), and perinatal mental health (Dubovi, 2018). One study did not clearly describe the topic focus of the virtual patient intervention (Nongmeikapam et al., 2019).

Virtual patient teaching and learning activities were divided between students working as individuals (n = 33) and in groups (n = 12). Data were unclear for one study (Warnell et al., 2005). Fifteen studies used spaced instruction, where the instruction is spread out and repeated over time (Berman et al., 2017; Bremner et al., 2020; Fog-Petersen et al., 2020; Hansen et al., 2020; Hayes-Roth, 2004; Lehmann et al., 2017; Wei Liu, 2021; Mastroleo et al., 2020; Matsumura et al., 2018; Pedersen et al., 2019; Rosen et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2020; Tanner et al., 2012; Washburn et al., 2016; Washburn et al., 2020).

Qualitative outcomes: common themes across qualitative and mixed-methods studies

Results of the abstracted themes are summarized in the Online Resource 5. The five qualitative studies used semi-structured interviews to explore students’ learning experiences with virtual patients, and were coded using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Although the research questions and analytical method in the mixed-methods studies varied from the qualitative studies, we identified four common themes across the study types: First, a safe learning environment that offered opportunities to repeat practice sessions was important for developing knowledge, self-efficacy, and confidence in the students. Second, authenticity was important for developing students’ empathy and understanding of the patient’s perspective. Virtual patient interventions using actors or real patients were perceived as being authentic (Pedersen et al., 2018, 2019; Verkuyl et al., 2017), while virtual patient interventions using avatars (Washburn et al., 2020) or a videotape of a simulation between an actor and a manikin (Kelly et al., 2020) were perceived as being less authentic. The two latter studies revealed that lack of authenticity negatively influenced students’ abilities to empathize with the patient. Third, students perceived the virtual patient interventions as valuable pedagogical models to provide a scaffolding of the mental health professional’s role in the clinical encounter with psychiatric patients. Fourth, integrated feedback was considered important for identifying knowledge gaps. In some of the reviewed qualitative and mixed-methods studies, students requested further feedback (Berman et al., 2017; Choi et al., 2020; Fog-Petersen et al., 2020; Kelly et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2020; Sunnqvist et al., 2016; Verkuyl et al., 2017).

Quantitative outcomes: knowledge, skills, and attitudes

All 17 no-intervention controlled studies reported significant and positive outcomes related to knowledge (n = 8), skills (n = 7), and attitudes (n = 10).

In the 11 non-media-comparative controlled studies, the results for outcomes related to knowledge (n = 4), skills (n = 3), and attitudes (n = 5) were mixed. In the studies that compared a virtual patient intervention with a live simulation, the results favored the live simulation (Nguyen et al., 2012; Robles et al., 2019; Warnell et al., 2005; Winkler et al., 2017). However, when compared to teaching as usual or a self-paced text-based intervention (where the patient case is described in text only), results favored the virtual patient intervention (Hansen et al., 2020; Hayes-Roth, 2004; Wei Liu, 2021; Mastroleo et al., 2020; Matsumura et al., 2018; Nongmeikapam et al., 2019; Pedersen et al., 2019).

In the 13 studies evaluating differences in outcomes between virtual patients and other educational technologies, seven studies showed no significant differences in outcomes related to knowledge (n = 2), skills (n = 5), or attitudes (n = 3). Two studies favored interactive patient scenarios over case presentations in terms of knowledge (Choi et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2008), skills (Choi et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2008), and attitudes (Choi et al., 2020). One study showed that dynamic screen-based virtual patients in comparison with static screen-based virtual patients enhanced skills significantly more (Foster et al., 2016). One study demonstrated that the virtual patient could be reliably used to discriminate novice learners from experienced learners (Martin, et al. 2020).

The thematic analysis of the primary outcomes with themes and subthemes related to knowledge, skills, and attitudes are summarized in the Online Resource 6. In Table 2 we present an example of our analysis.

Discussion

This review supports the finding that virtual patients can provide important and effective teaching to diverse healthcare students. Based on the findings from the qualitative and mixed-methods studies, we hypothesize that two main mechanisms are involved in learning from virtual patients; learning in a safe environment and the authenticity of the virtual patient.

While all interventions with virtual patients provide a safe environment in the sense that the student is not at risk of misdiagnosing, mistreating etc. a real patient, not all interventions are perceived as authentic by learners. By “authenticity” we refer to the ability of educational technologies to produce and render scenarios, experiences, and processes that closely resemble real life (Shaffer & Resnik, 1999). In the few studies that evaluated authenticity, the virtual patients based on videos of actors or actual patients were perceived as authentic. In contrast, students perceived virtual patients based on avatars as less authentic. However, the studies did not provide detailed descriptions of what aspects of the virtual patient case authenticity was related to, and no studies used a comparative design. Guise et al. (2012) suggest that observing natural human facial and bodily expressions and focusing on non-verbal communication may be particularly important to learning from virtual patients in psychiatry education (Guise et al., 2012). Nevertheless, perceived authenticity is not only a matter of human representation (Fredholm et al., 2019), as it can also refer to the interface, the patient story, or the learners’ tasks. Shaffer and Resnick (1999) introduced the concept of “thick” authenticity to account for these different kinds of authenticity. They also stressed that in addition to authenticity-related aspects of virtual patients, it is important to consider their relation to the world outside education.

The quantitative studies demonstrated that virtual patients, in comparison with no intervention, teaching as usual, and text-based interventions, have been consistently associated with better learning outcomes. However, they did not indicate any superiority of virtual patients over non-technological patient simulation. These results are in line with previous reviews examining the effectiveness of virtual patients in medical education (Abdool et al., 2017; Cook et al. 2010b; Cook & Triola, 2009; Kononowicz et al., 2019; Peddle et al., 2019; Piot et al., 2020). Nevertheless, there was uncertainty regarding the quality of the evidence as the majority of the quantitative studies included in the present review were of low-to-medium quality.

We extended our findings by systematically summarizing data related to the learning outcomes using thematic content analysis. We turn to a discussion of the themes we identified below.

Virtual patients and knowledge related outcomes

Based on the seventeen articles that evaluated outcomes related to students’ development of knowledge, we identified two major themes: Knowledge of symptomatology and knowledge of psychopathology.

Knowledge of symptomatology included which symptoms characterized specific disorders, which screening tools were relevant to include in the diagnostic interview, and which treatment options were available for specific disorders. Although the results of the review suggested that virtual patients were successful in facilitating the learning of such knowledge, there were no strong indications that they were significantly more effective than other methods of teaching.

Virtual patients may offer more in terms of learning about psychopathology as virtual patients, with their ability to represent a rich picture of the patient and the clinical encounter, can help students to develop knowledge that is more person-oriented and holistic than that afforded by other modalities.

Virtual patients and outcomes related to skills

Assessment of interpersonal and clinical skills was the focus of 20 studies. The thematic analysis showed that while interpersonal skills, such as communicative and patient-centered skills, were assessed across different healthcare education programs, assessment of specific clinical skills was more contingent on clinical roles. For example, diagnostic accuracy was the focus for medical students, while skills in advising care were the focus for students in nursing education.

We found that students had mostly been assessed based on interviews with virtual patients. While this demonstrates that virtual patients in psychiatry education have been used both as a training tool and a performance-based assessment tool, it did not show how learning worked, or what the generalizability was, including whether learning transferred to the clinical setting. For example, one study suggested that interaction with virtual patients enhanced students’ skills in diagnosing virtual patients but not simulated patients (Washburn et al., 2020).

Virtual patients and outcomes related to attitudes

Based on our analysis of the 19 studies that evaluated outcomes related to attitudes, we found two major themes: attitudes towards oneself, e.g., self-efficacy, and attitudes towards others, e.g., stigma.

Self-efficacy refers to students’ judgment of their capabilities to perform a particular task successfully. Competent functioning in a particular situation requires the necessary knowledge and skills as well as personal beliefs of efficacy to meet the demands of a specific situation (Bandura, 1977). By interacting with virtual patients, students’ self-efficacy improved after taking a patient’s history, conducting screening and assessment, and providing holistic and patient-centered care in a virtual patient activity. Following self-efficacy theory, the student’s conceptions of skills, based on their interaction with virtual patients, could serve as a guide for developing competencies and an internal standard for improving them.

Goffman (1990) defined stigma as an “attribute that is deeply discrediting” and that reduces the bearer “from a whole and usual person to a tainted, discounted one” (Goffman, 1990, p. 3). Individuals with mental illness have reported feeling devalued, dismissed, and dehumanized by health professionals (Hamilton et al., 2016) such that mental illness-related stigma can be a barrier to patient access to treatment and recovery (Abbey et al., 2011; Knaak et al., 2017; Thornicroft et al., 2007). Virtual patients, who portray the psychiatric setting and population more realistically, can help dispel and address stigma and attitudes before encountering a real patient.

Research gaps and directions for the future

The majority of the reviewed studies were carried out in the field of medical education. However, psychiatry is a specialty that requires collaboration, and interprofessional education is seen as a means of improving cooperative competencies and practices. Previous studies have reported significant challenges to interprofessional education, such as logistical problems and organizational barriers to planning sessions for students from different programs or universities (Priest et al., 2008). Future research should consider the role of virtual patients to improve interprofessional education, where students from different healthcare education programs could learn about, from, and with each other. For example, students from different programs could be allowed to work together on virtual patient scenarios in online platforms, or the virtual patient case could be designed in ways that allow the students to emulate the role of different healthcare professionals (e.g. nurse, doctor, social-worker).

We found that virtual patients have been used in especially geriatric psychiatry. This finding is surprising given that a recent scoping review on simulation-based education in healthcare suggests a dearth of research on the elderly population (Williams et al., 2017). We noted a lack of focus on pediatric patients and young adults with mental illness. Virtual patients can be specifically suited to address these patient populations because of their non-obtrusive interactions with an otherwise vulnerable patient population. We also noted a gap regarding transcultural undergraduate psychiatry education, which, given the increasing number of psychiatric patients with diverse ethnic backgrounds, is a health priority (Pantziaras et al., 2015).

Finally, the majority of the reviewed studies only focused on learners’ immediate performance following the educational intervention. The assumption seemed to be that any increase in levels of knowledge and skills or changes in attitudes evidenced immediately after the intervention represents the amount of learning that occurs from the intervention itself (Shariff et al., 2020). However, research suggests that peak performance immediately following training often overestimates the amount learned (Bjork & Bjork, 2011; Soderstrom & Bjork, 2015; Stefanidis et al., 2005). Thus, in addition to baseline and immediate post-intervention measures, future studies could include follow-up assessments to evaluate performance over time and focus on ongoing learning and extended retention of knowledge, skills, and attitudes (Kononowicz et al., 2020).

The strengths of this review was the use of thematic analysis to synthesize learning outcomes associated with the use of virtual patients, our comprehensive search strategies, and rigorous quality appraisals of the studies included in the review. By using a definition of virtual patients that was broader than that used in one previous review on virtual patients in medical education (Cook & Triola, 2009), we allowed for inclusion of interventions using different virtual patient formats. This made the findings more generalizable than if we had chosen a more narrowly focused set of literature.

Several limitations should be noted. First, articles published in languages other than English were excluded from this review, and data may have been missed. Second, the majority of the studies have been conducted in high-income countries. Although a previous review on virtual patients in medical education has collected positive evidence of effectiveness from both high-income and low-income countries (Kononowicz et al., 2019), we caution against simplistic conclusions about the cross-cultural effectiveness of virtual patients. Third, the greatest limitation across the included studies was the lack of or poor reporting of the validity of the evaluation instruments, indirectly providing the evidence base for study findings. Nevertheless, we did not exclude studies based on their quality due to our aim of providing an overview of all relevant research on virtual patients in psychiatry education during the past two decades. Still, in addition to the quality assessment, an assessment of risk of bias would have helped to establish transparency of the evidence synthesis. Fourth, the thematic analyses of learning outcomes revealed that the included studies lack the patient outcome data as described in Kirkpatrick’s four-level model for effective evaluation of educational training programs (Kirkpatrick, 1996). Such translation research serves an important role, and prudent pursuit of patient outcomes could advance the field.

In summary, in this systematic review, we identified 46 studies addressing the use of virtual patient interventions in undergraduate psychiatry education to develop students’ knowledge, skills, and attitudes, published between 2000 and January 2021. We investigated the most used approaches, examined the different learning outcomes, and described their effectiveness.

This review shows that virtual patients can afford valuable learning opportunities for students from different disciplines engaging in psychiatry education. Virtual patients, by providing access to safe, repeated, and consistent practice, can help students develop their knowledge about symptomatology and psychopathology and their interpersonal skills and clinical skills. Furthermore, virtual patients can help to increase students’ self-efficacy and confidence concerning their knowledge and skills. Finally, virtual patients can be used to develop more positive and less stigmatizing attitudes toward individuals with mental illness. However, we note that the predefined outcome measures in the studies included in our review did not fully cover the educational potential of virtual patients (Edelbring et al., 2011). More research is needed into how students use virtual patients and what benefits they afford.

References

Abbey, S., Charbonneau, M., Tranulis, C., Moss, P., Baici, W., Dabby, L., Gautam, M., & Paré, M. (2011). Stigma and discrimination. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 56(10), 1–9.

Abdool, P. S., Nirula, L., Bonato, S., Rajji, T. K., & Silver, I. L. (2017). Simulation in undergraduate psychiatry: Exploring the depth of learner engagement. Academic Psychiatry, 41(2), 251–261. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-016-0633-9

Andreatta, P. B., Hillard, M., & Krain, L. P. (2010). The impact of stress factors in simulation-based laparoscopic training. Surgery, 147(5), 631–639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2009.10.071

Balaguer, M., Pommée, T., Farinas, J., Pinquier, J., Woisard, V., & Speyer, R. (2020). Effects of oral and oropharyngeal cancer on speech intelligibility using acoustic analysis: Systematic review. Head & Neck, 42(1), 111–130.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191

Berman, A. H., Biguet, G., Stathakarou, N., Westin-Hägglöf, B., Jeding, K., McGrath, C., Zary, N., & Kononowicz, A. A. (2017). Virtual patients in a behavioral medicine massive open online course (MOOC): A qualitative and quantitative analysis of participants’ perceptions. Academic Psychiatry, 41(5), 631–641. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-017-0706-4

Bjork, E., & Bjork, R. (2011). Making things hard on yourself, but in a good way: Creating desirable difficulties to enhance learning.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Bremner, M. N., Maguire, M. B. R., Keen, D., Blake, B. J., Santa, H., & Nowalk, A. (2020). Implementation and evaluation of SBIRT training in a community health nursing course. Public Health Nursing, 37(2), 243–250. https://doi.org/10.1111/phn.12696

Brown, J. F. (2008). Applications of simulation technology in psychiatric mental health nursing education [Article]. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 15(8), 638–644. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2008.001281.x

Buijs-Spanjers, K. R., Hegge, H. H. M., Jansen, C. J., Hoogendoorn, E., & de Rooij, S. E. (2018). A web-based serious game on delirium as an educational intervention for medical students: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(10), 149–149. https://doi.org/10.2196/games.9886

Buijs-Spanjers, K. R., Hegge, H. H. M., Cnossen, F., Hoogendoorn, E., Jaarsma, D. A. D. C., & De Rooij, S. E. (2019). Dark play of serious games: Effectiveness and features (G4HE2018) [Article]. Games for Health Journal, 8(4), 301–306. https://doi.org/10.1089/g4h.2018.0126

Buijs-Spanjers, K. R., Harmsen, A., Hegge, H. H., Spook, J. E., De Rooij, S. E., & Jaarsma, D. A. D. C. (2020). The influence of a serious game's narrative on students' attitudes and learning experiences regarding delirium: An interview study [Article]. BMC Medical Education, 20(1), Article 289. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02210-5

Burmester, K. A., Ahluwalia, J. P., Ploutz-Snyder, R. J., & Strobbe, S. (2019). Interactive computer simulation for adolescent screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) for substance use in an undergraduate nursing program. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 49, 31–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2019.08.012

Chao, S. H., Brett, B., Wiecha, J. M., Norton, L. E., & Levine, S. A. (2012). Use of an online curriculum to teach delirium to fourth-year medical students: A comparison with lecture format. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 60(7), 1328–1332. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04035.x

Chen, A., Hanna, J. J., Manohar, A., & Tobia, A. (2018). Teaching empathy: The implementation of a video game into a psychiatry clerkship curriculum. Academic Psychiatry, 42(3), 362–365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-017-0862-6

Choi, H., Lee, U., Jeon, Y. S., & Kim, C. (2020). Efficacy of the computer simulation-based, interactive communication education program for nursing students. Nurse Education Today, 91, 104467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104467

Cook, D. A., & Reed, D. A. (2015). Appraising the quality of medical education research methods: The medical education research study quality instrument and the newcastle-ottawa scale-education. Academic Medicine, 90(8), 1067–1076. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000000786

Cook, D. A., & Triola, M. M. (2009). Virtual patients: a critical literature review and proposed next steps. Medical Education, 43(4), 303–311. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03286.x

Cook, D. A., Erwin, P. J., & Triola, M. M. (2010). Computerized virtual patients in health professions education: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Academic Medicine, 85(10), 1589–1602. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181edfe13

Dubovi, I. (2018). Designing for online computer-based clinical simulations: Evaluation of instructional approaches. Nurse Education Today, 69, 67–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2018.07.001

Edelbring, S., Dastmalchi, M., Hult, H., Lundberg, I. E., & Dahlgren, L. O. (2011). Experiencing virtual patients in clinical learning: A phenomenological study. Advances in Health Sciences Education: Theory and Practice, 16(3), 331–345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-010-9265-0

Fog-Petersen, C., Borgnakke, K., Hemmingsen, R., Gefke, M., & Arnfred, S. (2020). Clerkship students’ use of a video library for training the mental status examination. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 74(5), 332–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039488.2019.1709892

Foster, A., Chaudhary, N., Murphy, J., Lok, B., Waller, J., & Buckley, P. F. (2015). The use of simulation to teach suicide risk assessment to health profession trainees-rationale, methodology, and a proof of concept demonstration with a virtual patient. Academic Psychiatry, 39(6), 620–629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-014-0185-9

Foster, A., Chaudhary, N., Kim, T., Waller, J. L., Wong, J., Borish, M., Cordar, A., Lok, B., & Buckley, P. F. (2016). Using virtual patients to teach empathy: A randomized controlled study to enhance medical students’ empathic communication. Simul Healthc, 11(3), 181–189. https://doi.org/10.1097/sih.0000000000000142

Fredholm, A., Manninen, K., Hjelmqvist, H., & Silén, C. (2019). Authenticity made visible in medical students’ experiences of feeling like a doctor. International Journal of Medical Education, 10, 113–121. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.5cf7.d60c

Goffman, E. (1990). Stigma : notes on the management of spoiled identity ([New ed.]). Penguin.

Goldman, L. N., Wiecha, J., Hoffman, M., & Levine, S. A. (2008). Teaching geriatric assessment: Use of a hybrid method in a family medicine clerkship. Family Medicine, 40(10), 721–725.

Guise, V., Chambers, M., & Välimäki, M. (2012). What can virtual patient simulation offer mental health nursing education? Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 19(5), 410–418. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01797.x

Gutiérrez-Maldonado, J., Ferrer-García, M., Plasanjuanelo, J., Andrés-Pueyo, A., & Talarn-Caparrós, A. (2015). Virtual reality to train diagnostic skills in eating disorders. Comparison of two low cost systems. Stud Health Technol Inform, 219, 75–81.

Hamilton, S., Pinfold, V., Cotney, J., Couperthwaite, L., Matthews, J., Barret, K., Warren, S., Corker, E., Rose, D., Thornicroft, G., & Henderson, C. (2016). Qualitative analysis of mental health service users’ reported experiences of discrimination. Acta Psychiatrica Scand., 134, 14–22.

Hansen, J. R., Gefke, M., Hemmingsen, R., Fog-Petersen, C., Høegh, E. B., Wang, A., & Arnfred, S. M. (2020). E-library of authentic patient videos improves medical students’ mental status examination. Academic Psychiatry, 44(2), 192–195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-019-01130-x

Hayes-Roth, A. K., Saker, R., & Sephton, T. (2004). Training brief intervention with a virtual coach and virtual patients. Annual Review of Cybertherapy and Telemedicine, 2, 85–96.

Innovation, V. H. (2020). Covidence systematic review software, Melbourne, Australia. Available at www.covidence.org

Kelly, M., Lapkin, S., McGrath, B., Holloway, K., Nielsen, A., Stoyles, S., Campbell, M., Dieckmann, N. F., & Lasater, K. (2020). A blended learning activity to model clinical judgment in practice: A multisite evaluation. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 43, 10–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2020.03.006

Kerby, J., Calton, T., DiMambro, B., Flood, C., & Glazebrook, C. (2008). Anti-stigma films and medical student’s attitudes towards mental illness and psychiatry: Randomised controlled trial [Article]. Psychiatric Bulletin, 32(9), 345–349. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.107.017152

Kirkpatrick, D. (1996). Great ideas revisited: Revisiting Kirpatricks’s four-level model. Training and Development, 50(1), 54.

Kitay, B., Martin, A., Chilton, J., Amsalem, D., Duvivier, R., & Goldenberg, M. (2020). Electroconvulsive therapy: A video-based educational resource using standardized patients. Academic Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-020-01292-z

Kmet, L. M., Lee, R.C., & Cook, L.S. (2004). Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields. (HTA Initiative #13). Edmonton, AB: Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research,

Knaak, S., Mantler, E., & Szeto, A. (2017). Mental illness-related stigma in healthcare: Barriers to access and care and evidence-based solutions. Healthcare Management Forum, 30(2), 111–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/0840470416679413

Koetting, C., & Freed, P. (2017). Educating undergraduate psychiatric mental health nursing students in screening, brief intervention, referral to treatment (SBIRT) using an online. Interactive Simulation. Arch Psychiatr Nurs, 31(3), 241–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2016.11.004

Kononowicz, A. A., Zary, N., Edelbring, S., Corral, J., & Hege, I. (2015). Virtual patients - what are we talking about? A framework to classify the meanings of the term in healthcare education. BMC Medical Education, 15(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-015-0296-3

Kononowicz, A. A., Woodham, L. A., Edelbring, S., Stathakarou, N., Davies, D., Saxena, N., Tudor Car, L., Carlstedt-Duke, J., Car, J., & Zary, N. (2019). Virtual patient simulations in health professions education: Systematic review and meta-analysis by the digital health education collaboration. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(7), e14676–e14676. https://doi.org/10.2196/14676

Kononowicz, A. A., Hege, I., Edelbring, S., Sobocan, M., Huwendiek, S., & Durning, S. J. (2020). The need for longitudinal clinical reasoning teaching and assessment: Results of an international survey. Medical Teacher, 42(4), 457–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159x.2019.1708293

Kullberg, M. J., Mouthaan, J., Schoorl, M., de Beurs, D., Kenter, R. M. F., & Kerkhof, A. J. (2020). E-learning to improve suicide prevention practice skills among undergraduate psychology students: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Ment Health, 7(1), e14623.

Kunaparaju, S., Hidalgo, M. S., Bennett, D. S., & Sedky, K. (2018). The effect of administering a boundary course to third-year medical students during their psychiatry clerkship. Academic Psychiatry, 42(3), 371–375. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-018-0904-8

Kunst, E. L., Mitchell, M., & Johnston, A. N. (2017). Using simulation to improve the capability of undergraduate nursing students in mental health care. Nurse Education Today, 50, 29–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2016.12.012

Lee, J. D., Triola, M., Gillespie, C., Gourevitch, M. N., Hanley, K., Truncali, A., Zabar, S., & Kalet, A. (2008). Working with patients with alcohol problems: A controlled trial of the impact of a rich media web module on medical student performance. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 23(7), 1006–1009. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0557-5

Lehmann, S. W., Hemming, P., Rios, R., & Meriden, Z. (2017). Recognizing and managing geriatric depression: A two-part self-learning module set. MedEdPORTAL, 13, 10537.

Lipari, R. N., Hedden, S. L., & Hughes, A. (2013). Substance Use and Mental Health Estimates from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Overview of Findings. In The CBHSQ Report (pp. 1–10). Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US).

Liu, W. (2021). The effects of virtual simulation on undergraduate nursing students’ beliefs about prognosis and outcomes for people with mental disorders. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 50, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2020.09.007

Martin, A., Jacobs, A., Krause, R., & Amsalem, D. (2020a). The mental status exam: An online teaching exercise using video-based depictions by simulated patients. MedEdPORTAL, 16, 10947.

Martin, A., Krause, R., Jacobs, A., Chilton, J., & Amsalem, D. (2020b). The mental status exam through video clips of simulated psychiatric patients: An online educational resource. Academic Psychiatry, 44(2), 179–183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-019-01140-9

Mastroleo, N. R., Humm, L., Williams, C. M., Kiluk, B. D., Hoadley, A., & Magill, M. (2020). Initial testing of a computer-based simulation training module to support clinicians’ acquisition of CBT skills for substance use disorder treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 114, 108014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108014

Matsumura, Y., Shinno, H., Mori, T., & Nakamura, Y. (2018). Simulating clinical psychiatry for medical students: A comprehensive clinic simulator with virtual patients and an electronic medical record system. Academic Psychiatry, 42(5), 613–621. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-017-0860-8

McNaughton, N., Ravitz, P., Wadell, A., & Hodges, B. D. (2008). Psychiatric education and simulation: A review of the literature. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 53(2), 85–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370805300203

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Nguyen, E., Chen, T. F., & O’Reilly, C. L. (2012). Evaluating the impact of direct and indirect contact on the mental health stigma of pharmacy students. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 47(7), 1087–1098. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-011-0413-5

Nongmeikapam, M., Sarala, N., Reddy, M., & Ravishankar, S. (2019). Video-assisted teaching versus traditional didactic lecture in undergraduate psychiatry teaching. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 61(4), 376–379. https://doi.org/10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_265_18

Øgård-Repål, A., De Presno, K., & Fossum, M. (2018). Simulation with standardized patients to prepare undergraduate nursing students for mental health clinical practice: An integrative literature review [Article]. Nurse Education Today, 66, 149–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2018.04.018

Pantziaras, I., Fors, U., & Ekblad, S. (2015). Innovative training with virtual patients in transcultural psychiatry: The impact on resident psychiatrists’ confidence. PLoS ONE, 10(3), e0119754. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0119754

Patel, V., Chisholm, D., Parikh, R., Charlson, F. J., Degenhardt, L., Dua, T., Ferrari, A. J., Hyman, S., Laxminarayan, R., Levin, C., Lund, C., Medina Mora, M. E., Petersen, I., Scott, J., Shidhaye, R., Vijayakumar, L., Thornicroft, G., & Whiteford, H. (2016). Addressing the burden of mental, neurological, and substance use disorders: key messages from Disease Control Priorities, 3rd edition. Lancet, 387(10028), 1672–1685. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(15)00390-6

Peddle, M., McKenna, L., Bearman, M., & Nestel, D. (2019). Development of non-technical skills through virtual patients for undergraduate nursing students: An exploratory study. Nurse Education Today, 73, 94–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2018.11.008

Pedersen, K., Moeller, M. H., Paltved, C., Mors, O., Ringsted, C., & Morcke, A. M. (2018). Students’ learning experiences from didactic teaching sessions including patient case examples as either text or video: A qualitative study. Academic Psychiatry, 42(5), 622–629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-017-0814-1

Pedersen, K., Bennedsen, A., Rungø, B., Paltved, C., Morcke, A. M., Ringsted, C., & Mors, O. (2019). Evaluating the effectiveness of video cases to improve patient-centeredness in psychiatry: A quasi-experimental study. International Journal of Medical Education, 10, 195–202. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.5d9b.1e88

Piot, M. A., Dechartres, A., Attoe, C., Jollant, F., Lemogne, C., Layat Burn, C., Rethans, J. J., Michelet, D., Cross, S., Billon, G., Guerrier, G., Tesniere, A., & Falissard, B. (2020). Simulation in psychiatry for medical doctors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medical Education, 54(8), 696–708. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14166

Priest, H. M., Roberts, P., Dent, H., Blincoe, C., Lawton, D., & Armstrong, C. (2008). Interprofessional education and working in mental health: In search of the evidence base. Journal of Nursing Management, 16(4), 474–485. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2008.00867.x

Robles, M. J., Miralles, R., Esperanza, A., & Riera, M. (2019). Different ways to present clinical cases in a classroom: Video projection versus live representation of a simulated clinical scene with actors. BMC Medical Education, 19(1), 70. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1494-1

Rosen, J., Stiehl, E., Mittal, V., Fox, D., Hennon, J., Jeste, D., & Reynolds, C. F. (2013). Late-life mental health education for workforce development: Brain versus heart? The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 21(11), 1164–1167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.031

Shaffer, D. W., & Resnick, M. (1999). “Thick” authenticity: New media and authentic learning. Journal of Interactive Learning Research, 10(2), 195–215.

Shariff, F., Hatala, R., & Regehr, G. (2020). Learning after the simulation is over: The role of simulation in supporting ongoing self-regulated learning in practice. Academic Medicine, 95(4), 523–526. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000003078

Smith, M. J., Bornheimer, L. A., Li, J., Blajeski, S., Hiltz, B., Fischer, D. J., Check, K., & Ruffolo, M. (2020). Computerized clinical training simulations with virtual clients abusing alcohol: Initial feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness. Clinical Social Work Journal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-020-00779-4

Soderstrom, N. C., & Bjork, R. A. (2015). Learning versus performance: An integrative review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 176–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615569000

Speyer, R., Denman, D., Wilkes-Gillan, S., Chen, Y. W., Bogaardt, H., Kim, J. H., Heckathorn, D. E., & Cordier, R. (2018). Effects of telehealth by allied health professionals and nurses in rural and remote areas: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 50(3), 225–235. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-2297

Stefanidis, D., Korndorffer, J. R., Sierra, R., Touchard, C., Dunne, J. B., & Scott, D. J. (2005). Skill retention following proficiency-based laparoscopic simulator training. Surgery, 138(2), 165–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2005.06.002

Stubbings, L., Chaboyer, W., & McMurray, A. (2012). Nurses’ use of situation awareness in decision-making: an integrative review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 68(7), 1443–1453.

Sunnqvist, C., Karlsson, K., Lindell, L., & Fors, U. (2016). Virtual patient simulation in psychiatric care - A pilot study of digital support for collaborate learning. Nurse Education in Practice, 17, 30–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2016.02.004

Talbot, T., Sagae, K., John, B., & Rizzo, A. (2012). Sorting out the virtual patient: how to exploit artificial intelligence, game technology and sound educational practices to create engaging role-playing simulations. International Journal of Gaming and Computer-Mediated Simulations, 4, 1–19.

Tanner, T. B., Wilhelm, S. E., Rossie, K. M., & Metcalf, M. P. (2012). Web-based SBIRT skills training for health professional students and primary care providers. Substance Abuse, 33(3), 316–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2011.640151

Taverner, D., & White. (2000). Comparison of methods for teaching clinical skills in assessing and managing drug-seeking patients. Medical Education, 34(4), 285–291.

Thornicroft, G., Rose, D., & Kassam, A. (2007). Discrimination in health care against people with mental illness. International Review of Psychiatry, 19(2), 113–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540260701278937

Triola, M., Feldman, H., Kalet, A. L., Zabar, S., Kachur, E. K., Gillespie, C., Anderson, M., Griesser, C., & Lipkin, M. (2006). A randomized trial of teaching clinical skills using virtual and live standardized patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21(5), 424–429.

Vandyk, A. D., Lalonde, M., Merali, S., Wright, E., Bajnok, I., & Davies, B. (2018). The use of psychiatry-focused simulation in undergraduate nursing education: A systematic search and review [Review]. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 27(2), 514–535. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12419

Verkuyl, M., Hughes, M., Tsui, J., Betts, L., St-Amant, O., & Lapum, J. L. (2017). Virtual gaming simulation in nursing education: A focus group study. Journal of Nursing Education, 56(5), 274–280. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20170421-04

Verkuyl, M., Romaniuk, D., & Mastrilli, P. (2018). Virtual gaming simulation of a mental health assessment: A usability study. Nurse Education in Practice, 31, 83–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2018.05.007

Warnell, R. L., Duk, A. D., Christison, G. W., & Haviland, M. G. (2005). Teaching electroconvulsive therapy to medical students: Effects of instructional method on knowledge and attitudes. Academic Psychiatry, 29(5), 433–436. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ap.29.5.433

Washburn, M., Bordnick, P., & Rizzo, A. S. (2016). A pilot feasibility study of virtual patient simulation to enhance social work students’ brief mental health assessment skills. Social Work in Health Care, 55(9), 675–693. https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2016.1210715

Washburn, M., Parrish, D. E., & Bordnick, P. S. (2020). Virtual patient simulations for brief assessment of mental health disorders in integrated care settings. Social Work in Mental Health, 18(2), 121–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332985.2017.1336743

Williams, C., Aubin, S., Harkin, P., & Cottrell, D. (2001). A randomized, controlled, single-blind trial of teaching provided by a computer-based multimedia package versus lecture. Medical Education, 35(9), 847–854.

Williams, B., Reddy, P., Marshall, S., Beovich, B., & McKarney, L. (2017). Simulation and mental health outcomes: A scoping review. Adv Simul (lond), 2, 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41077-016-0035-9

Winkler, P., Janoušková, M., Kožený, J., Pasz, J., Mladá, K., Weissová, A., Tušková, E., & Evans-Lacko, S. (2017). Short video interventions to reduce mental health stigma: A multi-centre randomised controlled trial in nursing high schools. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(12), 1549–1557. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-017-1449-y

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

No ethical approval was needed, as the study did not involve any human or animal participants.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

10459_2023_10247_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for inclusion in a systematic review on virtual patients in undergraduate psychiatry education (PDF 642 KB)

10459_2023_10247_MOESM2_ESM.pdf

Search equation medline via pubmed for a systematic review on virtual patients in undergraduate psychiatry education (PDF 603 KB)

10459_2023_10247_MOESM3_ESM.pdf

Description and quality assessment scores of 46 studies included in a systematic review on virtual patients in undergraduate psychiatry education (PDF 763 KB)

10459_2023_10247_MOESM4_ESM.pdf

Virtual patient characteristics and educational characteristics of 46 studies included in a systematic review on virtual patients in undergraduate psychiatry education (PDF 928 KB)

10459_2023_10247_MOESM5_ESM.pdf

Description and themes extracted from the five qualitative studies and the seven mixed-methods studies included in a systematic review on virtual patients in undergraduate psychiatry education (PDF 601 KB)

10459_2023_10247_MOESM6_ESM.pdf

Virtual patients and their outcomes: themes and codes related to knowledge (Table @@1), skills (Table @@2), and attitudes (Table @@3) (PDF 596 KB)

10459_2023_10247_MOESM7_ESM.pdf

Additional details about 11 of the 46 studies included in a systematic review on virtual patients in undergraduate psychiatry education (PDF 553 KB)

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Jensen, R.A.A., Musaeus, P. & Pedersen, K. Virtual patients in undergraduate psychiatry education: a systematic review and synthesis. Adv in Health Sci Educ 29, 329–347 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-023-10247-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-023-10247-6