Abstract

Career selection in medicine is a complex and underexplored process. Most medical career studies performed in the U.S. focused on the effect of demographic variables and medical education debt on career choice. Considering ongoing U.S. physician workforce shortages and the trilateral adaptive model of career decision making, a robust assessment of professional attitudes and work-life preferences is necessary. The objective of this study was to explore and define the dominant viewpoints related to career choice selection in a cohort of U.S. IM residents. We administered an electronic Q-sort in which 218 IM residents sorted 50 statements reflecting the spectrum of opinions that influence postgraduate career choice decisions. Participants provided comments that explained the reasoning behind their individual responses. In the final year of residency training, we ascertained participating residents’ chosen career. Factor analysis grouped similar sorts and revealed four distinct viewpoints. We characterized the viewpoints as “Fellowship-Bound-Academic,” “Altruistic-Longitudinal-Generalist,” “Inpatient-Burnout-Aware,” and “Lifestyle-Focused-Consultant.” There is concordance between residents who loaded significantly onto a viewpoint and their ultimate career choice. Four dominant career choice viewpoints were found among contemporary U.S. IM residents. These viewpoints reflect the intersection of competing priorities, personal interests, professional identity, socio-economic factors, and work/life satisfaction. Better appreciation of determinants of IM residents’ career choices may help address workforce shortages and enhance professional satisfaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Many factors contribute to medical graduates’ decisions about their chosen career path.

In the US, nearly one-quarter of all postgraduate training positions are in Internal Medicine (IM) (NRMP, 2020). Therefore, there is great interest in IM trainees’ career choices because they influence both the depth and breadth of the entire US physician workforce, which may not always align with societal needs. Despite a great need for primary care physicians in the US, interest in primary care careers has declined among internal medicine (IM) residents over the last 20 years (West & Dupras, 2012, Garibaldi et al., 2005). Among the IM subspecialties, some (like cardiology and gastroenterology) are highly competitive and consistently fill 99% of their available training positions (NRMP, 2020). In contrast, other subspecialties like geriatrics and nephrology have seen a drastic decline in applications and filled positions in recent years, leading to concerns about unmet community needs and impending workforce shortages (NRMP, 2020, Parker et al., 2011).

Due to disparities between IM physician supply and societal need, researchers have looked for the variables that associate with career selection. Prior studies of North American IM trainees have identified many socio-demographic factors (age, gender, race, marital status, and educational debt) and professional preferences (time with family, opportunities for procedures, work/life balance, intellectual interest, patient continuity, scope of practice, remuneration, and the presence of a mentor) that associate with career selection (Kassebaum and Szenas, 1992, Hauer et al., 2008, Kassebaum & Szenas, 1994, Dorsey et al., 2003, Dorsey et al., 2005, Diehl et al., 2006, McDonald et al., 2008, Garibaldi et al., 2005, West et al., 2009, Horn et al., 2008, Daniels & Kassam, 2011, Douglas et al., 2018). In both the UK and Australia, recent longitudinal surveys of graduating medical students and junior physicians observed similar trends regarding the influence of expected future income, controllable work hours, lifestyle, and intrinsic interest in general practice on final career selection (Cleland et al., 2014; Kumwenda et al., 2019; Sivey et al., 2012; Lennon et al., 2019).

However, the relevance of these studies to the US workforce is limited for two reasons. First, many of these studies are outdated. Since 2005, the medical workforce has changed: there are now more female than male graduates of U.S. medical schools (AAMC, 2020), the current generation of workers are more willing to make career sacrifices to share family responsibilities compared to prior generations (Global Generations, 2018), and in the US, hospital medicine has emerged as a popular, alternate pathway to primary care or subspecialization (Ratelle et al., 2014). Second, we now recognize that residents experience high levels of burnout and low professional satisfaction during training (Dyrbye et al., 2014, 2016; Ludmerer, 2005). When studied recently, burnout and professional satisfaction during training directly affects career choice decisions, career choice regret, and breadth of the physician workforce (Dyrbye et al., 2018; Lennon et al., 2020). However, burnout and professional satisfaction were conspicuously not assessed in earlier IM-focused career choice studies.

These existing studies mostly focused on individual demographics and conscious preferences during medical school (before entering the workforce.) To better understand career decision making, an updated theory on career selection is needed. Historical approaches to career selection relied on trait-factor theory, which proposed that career selection is made by simply matching individual traits to work requirements (Parsons, 1909). Krieshok et al. (2009) proposes an updated theory of career decision making, called the trilateral adaptive model. This theory places greater emphasis on the interplay between conscious/rational, non-conscious/intuitive thoughts, and how these thoughts are influenced by adapting to an ever-changing environment. In the context of medical career decision making, the trilateral adaptive model suggests that occupational enrichment during post-graduate residency training is the optimal time for exploration, socialization, and having the experiences that test the individual’s flexibility, resilience, and tolerance for ambiguity. Occupational engagement plus the interplay between rational and intuitive thoughts here serves as a catalyst for professional identity formation (Cruess et al., 2015) and career decision making.

Medical career choice decisions are inherently complex processes driven by a multitude of subjective variables and experiences that vary in importance from person to person. Likert scale surveys have been used to measure subjectivity, but quantitative analysis of these responses is fraught with methodologic assumptions (confusion between ordinal and interval scales) and systematic errors (Jamieson, 2004). For example, Likert scale surveys are sensitive to desirability bias and response-style bias, in which content-irrelevant factors (survey structure, question characteristics, category characteristics, and response scale characteristics) influence the participants’ responses (Kieruj & Moors, 2010; Baumgartner & Steenkamp, 2001). Collectively, these issues limit the ability to intercorrelate resident preferences and draw meaningful conclusions from Likert scale surveys. Some researchers have evaluated physician career preferences with the more robust discrete choice experiment (Kalb et al., 2018), which is an experiment used to elicit preferences without directly asking participants to state them. While helpful for analyzing latent preferences regarding specific decisions or trade-offs, the discrete choice experiment is not designed to understand the various ‘types’ of decision makers across the spectrum of potential variables. Also, this type of study has not been performed on US IM trainees, who exist in a unique socio-cultural training context compared to other countries. Informed by the trilateral adaptive model of career decision making, we believe a different, exploratory research approach is needed to better understand the number and diversity of unique viewpoints regarding career choice selection among IM trainees.

We chose to use Q-methodology, which is a mixed methodology for defining subjective viewpoints (Brown, 1996; McKeown & Thomas, 2013). In Q-methodology, subjects rank a series of relevant declarative statements against all others to elicit a hierarchy of agreement, which overcomes the systematic errors seen in Likert scale surveys. This allows the researcher to intercorrelate dimensions of subjectivity between the participants. In other words, the purpose is to identify the number and types of viewpoints present, not to test the proportional distribution of these viewpoints within the larger population (Valenta & Wigger, 1997; Watts & Stenner, 2012). Informed by the trilateral adaptive model of career selection, our primary objective is to explore and identify the latent variables or ‘types’ of decision-makers in a cohort of US IM residents. Our secondary objective was to measure associations between any identified viewpoint groupings and final career choice made at the end of residency training.

Materials and methods

Q-methodology

Q-methodology is an approach to study subjectivity. We chose to perform an exploratory Q-study that allowed IM residents to define what matters most for career decisions. Q-methodology allows the researcher to extract and describe the unique viewpoints by performing factor analysis on participants’ Q-sorts. As opposed to typical factor analysis, the variables are the individuals (not traits of the individuals), and the validity of the results is less sensitive to sample size or response rates (Valenta & Wigger, 1997). Participants in a Q-study create Q-sorts by placing a series of statements onto a score sheet that has been ranked with columns representing the spectrum from most disagree to most agree. This design allows the participant to provide a snapshot of their subjective viewpoint. Finally, participants give commentary on statements ranked at each extreme column of the distribution map. All the Q-sorts are then subjected to by-person factor analysis, which identifies latent correlations between participants (not participant traits). A viewpoint profile is defined by the unique list of distinguishing statements and scores on the agree-disagree spectrum, such that a composite Q-sort is created for each viewpoint. The narrative comments associated with statements can then be used to understand the rationale for the statement scores.

Definition of the Q-sample

In a Q-study, the researchers develop the set of statements to be sorted. To generate the set of statements for this study, we examined peer-reviewed journal articles that studied IM resident career selection (West & Dupras, 2012; Garibaldi et al., 2005; Kassebaum & Szenas, 1992; Hauer et al., 2008; Kassebaum & Szenas, 1994; Dorsey et al., 2003; Dorsey et al., 2005; Diehl et al., 2006; McDonald et al., 2008; Garibaldi et al., 2005; West et al., 2009; Horn et al., 2008; Daniels & Kassam, 2011; Ratelle et al., 2014; Dyrbye et al., 2014, 2018; Daniels & Kassam, 2013; Douglas et al., 2018). The lead researcher (JKR) formulated a concourse of 75 statements, including statements from a study of Canadian IM residents (Daniels & Kassam, 2013), used with permission. Two investigators with experience writing Q-sort statements (JKR and CWH) (Roberts et al., 2015, Roberts et al., 2016, Dotters-Katz et al., 2016, Hargett et al., 2017) were selected to group the statements into relevant themes and judge them according to thematic completeness and relevance. All statements were crafted to be legible, unambiguous, and not overly positive or negative in tone. The investigators refined, deleted, and combined statements in each thematic group to arrive at a final set of 50 statements across the themes thought to influence career selection (See Fig. 1 for the final statement set organized by theme.)

Study sites and population

The study included IM residents at ten accredited U.S residency training programs. We first conducted a pilot study at Duke University Medical Center between November 2018 and January 2019. In the pilot, we observed no problems with the Q-sort procedure or any problems regarding any statements in the Q-sample. We then continued the study at the following residency programs between November 2019 through February 2020: Rush University, Stanford University, University of Colorado, Oregon Health & Science University, Northwestern University, University of Iowa-Des Moines, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, and Mount Sinai Hospital. We chose these sites based on the program’s willingness to participate and our desire to achieve broad geographic representation. Individual training programs invited their residents to complete the survey during the study period. Resident participation was voluntary, and a raffle for $50 Amazon gift cards was used to incentivize participation.

Procedure and data collection

We delivered the survey electronically using FlashQ (Version 1.0, Hackert and Braehler, Germany), a web-based program designed to administer a Q-study. Supplemental Fig. 1 shows the procedure for completing the Q-study. First, FlashQ randomly presented each of the 50 statements as a card to be sorted into one of three initial piles: agree, neutral, or disagree. Next, the resident was asked to pull cards from these piles and place them into the Q-Sort diagram columns rated from strongly agree (+ 5) to strongly disagree (-5). Participants were given a final option to swap card positions across the diagram. At the conclusion of the survey, all columns on the score sheet were occupied by a statement card. Finally, participants had the opportunity to provide written commentary on the two statements with which they most agreed and most disagreed.

We collected sociodemographic information including gender, age at medical school graduation, training site location, post-graduate training year, educational debt, and residents’ final career choice, which was defined as the career chosen at the beginning of their final year of training. Residents who had not yet decided on final careers and residents who did not provide identifying information were counted as missing. Compensation categories (normal vs. high) were defined according to a recent physician salary survey (Medscape, 2019). Specialties with an average physician salary that was within $50,000 of the mean salary for general IM were coded as “normal compensation.” Specialties with an average physician salary greater than $50,000 above the mean salary for general IM were coded as “high compensation” careers.

Factor analysis

We used PQMethod software (Version 2.33, Schmolck, Germany), which performs by-person factor analysis. We input 218 sorts into PQMethod software, which then created an inter-correlation matrix for the participants. We extracted factors according to Horst’s centroid method, followed by varimax rotation. We extracted factors and chose the factor solution according to published methodological criteria (factor eigenvalues > 1) (Watts and Stenner, 2012) and whether the solution had a coherent interpretation supported by the narrative comments. Using Horst’s method, PQMethod extracted four factors and stopped after reaching the limiting level of residual correlations (further factor extraction explained < 3% of residual variance). A five and six-factor solution was also analyzed, and we thought that the four-factor solution was the most coherent and best supported by narrative commentary. A “defining sort” was any sort that loaded significantly (γ > 0.32 for a 95% confidence interval) on only one unique factor. The authors interpreted the defining Q-sort matrix, read the associated narrative comments, and found consensus on the appropriate label for each of the four profiles.

Statistical analysis

We conducted all quantitative analyses in STATA, version 14.0 (Statacorp, College Station, Texas). Normally distributed data are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Age was treated as a continuous variable and compared across groups using t-tests (analyses of 2 groups) or one-way analysis of variance (analyses of > 2 groups). Two-tailed P values less than 5% were considered statistically significant. We used the Bonferroni correction in instances of multiple comparisons. Gender was analyzed as female, male, and non-binary. Educational debt was analyzed categorically as no debt, < $100,000, $100,000–300,000, and > $300,000. Geographic training site was analyzed as Southeast, Northeast, Central, and West. To compare the association of demographic variables with viewpoint groups, we performed multinomial logistic regression with the viewpoint groups as the dependent variable and demographics as predictors. To investigate associations of the four career choice viewpoints with ultimate career choice categories (high vs. low compensation, inpatient vs. outpatient, subspecialty vs. general IM), we used logistic regression including the viewpoint groups as the independent variable and career categories as the outcome variables. For both sets of analyses, the “Unaffiliated” group (residents who did not statistically sort into a defined viewpoint) served as the referent viewpoint group.

All participant responses were kept confidential and private. Resident responses were not released or shared with residency program leadership. Participation in the study was voluntary.

The Duke Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved this study prior to data collection.

Results

A total of 218 residents participated in the Q-study. 161 (74%) of the respondents identified as being in the PGY-2 year of training or above. The mean age at the time of medical school graduation was 26.9 (2.2). 130 (60%) of the respondents identified having educational debt. Geographically, more participants were from the Southern (31%) and Western regions (33%), compared to the Northeast (17%) and Midwest (19%). 102 (47%) identified as female, 94 (43%) identified as male, and 2 (1%) identified as non-binary.

Descriptions of four career choice viewpoints

We characterized resident career choice profiles according to the four-factor solution. Residents that were not uniquely associated with a single factor were placed in the “Unaffiliated” group. Table 1 shows the correlations between factor scores for each factor. Figure 1 contains the representative (composite) Q-sorts for each of the four viewpoints. Positive Q-sort values represent agreement and negative values represent disagreement with the statement. Table 2 lists representative comments from residents who defined each factor. The comments are aggregated according to the broad subject domains from which the associated statements came.

Fellowship-bound-academic (Factor 1)

This group was defined by 63 residents. These residents are driven primarily by an interest in human physiology and career in academic medicine. They strongly value having future opportunities to conduct research and teach others. Their career interests have been influenced by the presence of a mentor or faculty role model. They are interested in becoming an expert in a single area as opposed to working as a generalist. They are also interested in performing procedures as a part of their clinical practice. Career decisions for this group are less affected by the presence of student loan debt, but instead they are primarily driven by intellectual curiosity, teaching, and scholarly work. Therefore, this group is looking forward to the professional development opportunities of a fellowship training program. These residents are not interested in finishing their training as soon as possible: they are lifelong learners who are willing to train as long as is necessary to achieve their desired career.

Altruistic-longitudinal-generalist (Factor 2)

This group was defined by 43 residents. This group embraces holistic patient care, and they are sustained by clinical variety and close, longitudinal relationships with patients. They do not have much interest in being the expert or consultant, but instead seek ownership and assuming longitudinal responsibility for their patients’ care. To achieve this, they prefer an outpatient/ambulatory practice as opposed to an inpatient-based practice. They are not motivated by interest in single organ diseases, research, or human physiology, but instead they enjoy a broad range of clinical interests and patient care responsibilities. They have a strong interest in teaching residents and students. They value having personal time and are willing to make career sacrifices to achieve better work-life balance, acknowledging that self-care will help them be better doctors. Their career choices are not affected by student loan debt or remuneration, but instead they are highly motivated to care for underserved patients and reduce disparities through their practice.

Inpatient-burnout-aware (Factor 3)

This group was defined by 34 residents. These residents strongly prefer acute, episodic patient care in the inpatient setting. This group enjoys a wide variety of practice over specialization, but they strongly prefer the inpatient setting in part due to more predictable time management and control compared to the outpatient setting. They are not motivated by research interests or specific single organ diseases but are instead interested in a little bit of everything. They strongly value having more personal time and lifestyle control, and they are willing to make career sacrifices to obtain a good work-life balance. They have thought hard about the consequences of physician burnout and have considered this risk when deciding a career. They are not willing to endure any more years of training: they are eager to finish and start a career that pays well given how long they have been a student/trainee thus far.

Lifestyle-focused consultant (Factor 4)

This group was defined by 33 residents. They strongly value preserving personal time and having considerable control over their lifestyle and future practice. They prefer being a consultant with expertise in a single area as opposed to being a generalist. They also have a strong preference for outpatient, longitudinal care and they have an aversion to episodic, inpatient care. They are not motivated by research interests or working with underserved patients. Instead, they are strongly interested in a career that pays well and will be in demand with good job prospects. They are mindful of physician burnout, but they are especially sensitive to physician remuneration, desiring a career that will pay well. The narrative comments for this group (see Table 2) suggest how high levels of student loan debt influence this perspective.

Effects of demographics on viewpoint group

Multinomial regression analysis on age at medical school graduation only showed a significant association between age and being in the “Altruistic-Longitudinal-Generalist” group (OR per year 1.43, 95% CI 1.11–1.85, P < 0.006). Multinomial regression on gender categories, educational debt categories, and PGY year showed no significant associations with viewpoint groups.

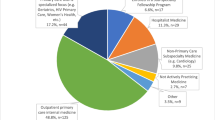

Final career choice

Table 3 shows residents’ final career choices according to their Q-sort derived profiles. For each of the four viewpoints, we observed concordance between the residents’ practice preferences and the career they ultimately chose. Figure 2 shows the odds of choosing a career category (subspecialty vs. general IM, inpatient vs. outpatient career, and high compensation vs. normal compensation career) according to being a defining member of one of the four viewpoints. Age, gender, geographic region, and medical education debt were not associated with choice according to the career categories.

Odds of Choosing Certain type of Career According to the Four Viewpoints Derived from the Q-sort Activity. A Odds ratios (OR) for choosing a sub-specialty career; B OR for choosing an inpatient-based career; and C OR for choosing a “high compensation” career. The referent group is the “Unaffiliated” group of residents who did not load into any of the four factors

Discussion

We distinguished IM residents in the US according to four career choice profiles that reflect characteristic covariation according to practice preferences, intellectual interests, professional identity, socio-economic factors, concerns about work/life balance and professional burnout. These findings advance the discussion of career selection in the modern era. In line with an existing Q study (Daniels and Kassam, 2013), we observed a group that was interested in sub-specialization, longer training time, and interest in procedures (“Fellowship-Bound Academic”). In follow up, most of the residents in this group went into subspecialties like Cardiology, Pulmonary-Critical Care Medicine, Hematology-Oncology, and Infectious Disease. While we also identified some residents with a strong preference for variety and general internal medicine (GIM) like Daniels and Kassam (2013), we were able to further distinguish them in two viewpoints (“Altruistic-Longitudinal-Generalist” and “Inpatient-Burnout Aware”) that primarily differed according to location of practice, patient continuity, altruism, remuneration, and concerns over burnout. Consistent with our factor grouping, most of the residents in the “Altruistic-Longitudinal-Generalist” group chose a GIM-primary care career, while most of the residents in the “Inpatient-Burnout Aware” group chose a GIM-hospitalist career. Unlike existing studies, we observed the novel influence of physician burnout, negative attitudes towards hospitalized patients, concerns about work-life integration, perceived prestige, loss of physician autonomy, and remuneration concerns, particularly among the “Inpatient-Burnout-Aware” and “Lifestyle-Focused Consultant” groups. These attitudes are congruent to a country with high medical education costs, fee-for-service payment structure, and structural bias against general practice (Rosenthal et al., 1994; Dowdy, 2011; Greysen et al., 2011; Palmeri et al. 2010). In follow-up, most of the residents who made up the “Lifestyle-Focused Consultant” group went into high remuneration specialties like Gastroenterology and Hematology-Oncology.

Our findings align with contemporary professional identity formation and career decision theories. For example, Cruess et al. (2015) applied social learning theory concepts like communities of practice (Wenger, 1998) and situated learning (Lave & Wenger, 1991) to describe professional identity formation in medical education. In this framework, socialization in the training environment is influenced by a multitude of different factors (clinical/non-clinical experiences, role-models/mentors, and internal or external attitudes) through either conscious reflection or unconscious acquisition. In terms of identity formation, the significance of each varies from person to person. For example, in our study, having a role-model/mentor and positive attitudes towards research/scholarship uniquely influenced the “Fellowship-Bound Academic,” while aversion to inpatient general medicine and a desire for control and high remuneration influenced the “Lifestyle-Focused Consultant.” Witnessing physician burnout (or perhaps experiencing burnout themselves) uniquely influenced the “Inpatient-Burnout Aware” residents in their career choice. In accordance with the trilateral adaptive model of career decision making, our results demonstrate how professional identity and career choices are influenced by occupational enrichment and how the individual responds to a complex and changing environment.

These results raise questions worthy of future investigation. For example, how stable are these viewpoints over time? To what extent, if any, have these attitudes changed from matriculation into medical school through the final year of residency? To what extent does burnout during residency training or perceptions of burnout in different careers influence final career selection? To what extent are attitudes intrinsic to the trainee vs. adopted by the trainee as they align with perceived values of a given specialty?

Until that work is complete, we’ve identified some practical uses for these results. First, careers or subspecialties with workforce shortages could use these foundational viewpoints to guide educational efforts, career advertising, or practice overhaul to restore recruitment. For example, subspecialties at risk of workforce shortages could tailor clinical training experiences to better reflect the breadth of practice opportunities within the subspecialty. Second, knowledge of these viewpoints can inform discussions and policy decisions aimed at addressing residency training environments, professional satisfaction, and trainee burnout. For example, our results raise questions about inpatient learning environments and the negative experiences that might influence practice preferences and career decisions. Third, while our results reflect attitudes and perspectives of trainees in the US, the Q-sort activity presented here could be easily replicated in other countries, providing a robust assessment of trainee preferences in different contexts. Finally, because resident viewpoints correlate well with final career choice, the Q-sort activity could be used by individual training programs as a formative career self-assessment. The sorting task could help an undecided resident prioritize her/his interests and preferences, leading to fruitful discussions, coaching, and career counseling from the program leadership.

Our study has limitations. First, the single assessment of resident perspectives means that these viewpoints reflect those at a single time point in training. A small proportion of our sample (11%) were first-year residents (PGY-1). It is likely that length of training is correlated with an established professional identity and a more stable Q-sort viewpoint, thus the PGY-1 resident responses may change with time (West et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2020). Therefore, our study targeted residents in the PGY-2 level or above, a time point when residents are nearing completion of their training, attitudes are solidified, and career decisions are finalized. Second, the statement set itself could introduce systematic bias if the statements are ambiguously or extremely worded. However, use of a forced distribution mitigates against this. Third, response bias could exist if participants perceived certain responses as more socially acceptable rather than true to their subjective experience. Fourth, our study included only US IM trainees, so the results may be less generalizable to trainees in other countries. Finally, it is worth noting that the defining statements for each viewpoint represent attitudes that are intercorrelated, and we cannot make conclusions about causation or sequencing of attitude development.

Values, attitudes, and lived experiences are all involved in the complex processes that are professional identity formation and career selection. In a contemporary cohort of IM trainees, we identified four dominant types of residents through the lens of professional identity and career choice decisions. For better or worse, a substantial number of US physicians are making these decisions in accordance with the viewpoints we identified through by-person factor analysis. Knowledge of these viewpoints can inform discussions and policy decisions designed to balance the desires of the individual, the goals of the training program, and the needs of our patients and their communities.

References

American Association of Medical Colleges. (2020). Applicant and matriculant data tables. https://www.aamc.org/data/facts/applicantmatriculant/.

Baumgartner, H., & Steenkamp, J. E. M. (2001). Response styles in marketing research: A cross-national investigation. Journal of Marketing Research., 38, 143–156.

Brown, S. R. (1996). Q methodology and qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research, 13, 561–567.

Cleland, J. A., Johnston, P. W., Anthony, M., Khan, N., & Scott, N. W. (2014). A survey of factors influencing career preference in new-entrant and exiting medical students from four UK medical schools. BMC Medical Education, 14, 151.

Cruess, R. L., Cruess, S. R., Boudreau, J. D., Snell, L., & Steinert, Y. (2015). A schematic representation of the professional identity formation and socialization of medical students and residents: A guide for medical educators. Academic Medicine, 90, 718–725.

Daniels, V. J., & Kassam, N. (2011). Determinants of internal medicine residents’ choice in the Canadian R4 fellowship match: A qualitative study. BMC Medical Education, 11, 44.

Daniels, V. J., & Kassam, N. (2013). Impact of personal goals on the internal medicine R4 subspecialty match: A Q methodology study. BMC Medical Education, 13, 171.

Diehl, A. K., Kumar, V., Gateley, A., Appleby, J. L., & O’Keefe, M. E. (2006). Predictors of final specialty choice by internal medicine residents. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21, 1045–1049.

Dorsey, E. R., Jarjoura, D., & Rutecki, G. W. (2003). Influence of controllable lifestyle on recent trends in specialty choice by US medical students. JAMA, 290, 1173–1178.

Dorsey, E. R., Jarjoura, D., & Rutecki, G. W. (2005). The influence of controllable lifestyle and sex on the specialty choices of graduating US medical students, 1996–2003. Academic Medicine, 80, 791–796.

Dotters-Katz, S., Hargett, C. W., Zaas, A. K., & Criscione-Schreiber, L. G. (2016). What motivates residents to teach? The attitudes in clinical teaching study. Medical Education, 50(7), 768–777.

Douglas, P. S., Rzeszut, A. K., Bairey Merz, C. N., Duvernoy, C. S., Lewis, S. J., Walsh, M. N., Gillam, L., College, A., & of Cardiology Task Force on Diversity and Inclusion and American College of Cardiology Women in Cardiology Council. (2018). Career preferences and perceptions of cardiology among US internal medicine trainees: factors influencing cardiology career choice. JAMA Cardiology, 3(8), 682–691.

Dowdy, D. W. (2011). Trained to avoid primary care. Annals of Internal Medicine, 154, 776–777.

Dyrbye, L. N., Burke, S. E., Hardeman, R. R., Herrin, J., Wittlin, N. M., Yeazel, M., Dovidio, J. F., Cunningham, B., White, R. O., Phelan, S. M., Satele, D. V., Shanafelt, T. D., & van Ryn, M. (2018). Association of clinical specialty with symptoms of burnout and career choice regret among US resident physicians. JAMA, 320, 1114–1130.

Dyrbye, L. N., West, C. P., Satele, D., Boone, S., Tan, L., Sloan, J., & Shanafelt, T. D. (2014). Burnout among U.S. medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Academic Medicine, 89, 443–451.

Dyrbye, L., & Shanafelt, T. (2016). A narrative review on burnout experienced by medical students and residents. Medical Education, 50(1), 132–149.

Garibaldi, R. A., Popkave, C., & Bylsma, W. (2005). Career plans for trainees in internal medicine residency programs. Academic Medicine, 80, 507–512.

Global Generations. (2018). A global study on work-life challenges across generations. https://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/EY-global-generations-a-global-study-on-work-life-challenges-across-generations/$FILE/EY-global-generations-a-global-study-on-work-life-challenges-across-generations.pdf.

Greysen, S. R., Chen, C., & Mullan, F. (2011). A history of medical student debt: Observations and implications for the future of medical education. Academic Medicine., 86, 840–845.

Hargett, C. W., Doty, J. P., Hauck, J. N., Webb, A. M., Cook, S. H., Tsipis, N. E., Neumann, J. A., Andolsek, K. M., & Taylor, D. C. (2017). Developing a model for effective leadership in healthcare: A concept mapping approach. Journal of Healthcare Leadership, 28(9), 69–78.

Hauer, K. E., Durning, S. J., Kernan, W. N., et al. (2008). Factors associated with medical students’ career choices regarding internal medicine. JAMA, 300, 1154–1164.

Horn, L., Tzanetos, K., Thorpe, K., & Straus, S. E. (2008). Factors associated with the subspecialty choices of internal medicine residents in Canada. BMC Medical Education, 8, 37.

Jamieson, S. (2004). Likert scales: How to (ab)use them. Medical Education, 38, 1217–1218.

Kalb, G., Kuehnle, D., Scott, A., Cheng, T. C., & Jeon, S. H. (2018). What factors affect physicians’ labour supply: Comparing structural discrete choice and reduced-form approaches. Health Economics, 27(2), e101–e119.

Kassebaum, D. G., & Szenas, P. L. (1992). Relationship between indebtedness and the specialty choices of graduating medical students. Academic Medicine, 67, 700–707.

Kassebaum, D. G., & Szenas, P. L. (1994). Factors influencing the specialty choices of 1993 medical school graduates. Academic Medicine, 69, 164–170.

Kieruj, N., & Moors, G. (2010). Variations in response style behaviour by response scale format in attitude research. Journal of Public Opinion Research., 22, 320–342.

Krieshok, T. S., Black, M. D., & McKay, R. A. (2009). Career decision making: The limits of rationality and the abundance of non-conscious processes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 75, 275–279.

Kumwenda, B., Cleland, J., Prescott, G., Walker, K., & Johnston, P. (2019). Relationship between sociodemographic factors and specialty destination of UK trainee doctors: A national cohort study. British Medical Journal Open, 9(3), e026961.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

Lennon, M., O’Sullivan, B., McGrail, M., Russell, D., Suttie, J., & Preddy, J. (2019). Attracting junior doctors to rural centres: A national study of work-life conditions and satisfaction. The Australian Journal of Rural Health, 27, 482–488.

Lennon, M. J., McGrail, M. R., O’Sullivan, B., Tan, A., Mok, C., Suttie, J. J., & Preddy, J. (2020). Understanding the professional satisfaction of hospital trainees in Australia. Medical Education, 54(5), 419–426.

Ludmerer, K. (2005). Time to heal: American medical education from the turn of the century to the era of managed care. Oxford University Press.

McDonald, F. S., West, C. P., Popkave, C., & Kolars, J. C. (2008). Educational debt and reported career plans among internal medicine residents. Annals of Internal Medicine, 149, 416–420.

McKeown, B., & Thomas, D. (2013). Q methodology (quantitative applications in the social sciences). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2nd Edition.

Medscape: Physician Compensation Report 2019. https://www.medscapecom/slideshow/2019-compensation-nephrologist-6011335#1.

National Resident Matching Program. (2020). Results and data specialties matching service. Appointment year. https://mk0nrmp3oyqui6wqfm.kinstacdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Results-and-Data-SMS-2020.pdf.

Palmeri, M., Pipas, C., Wadsworth, E., & Zubkoff, M. (2010). Economic impact of a primary care career: A harsh reality for medical students and the nation. Academic Medicine., 85, 1692–1697.

Parker, M. G., Ibrahim, T., Shaffer, R., Rosner, M. H., & Molitoris, B. A. (2011). The future nephrology workforce: Will there be one? Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 6, 1501–1506.

Parsons, F. (1909). Choosing a vocation. Houghton Mifflin.

Ratelle, J. T., Dupras, D. M., Alguire, P., Masters, P., Weissman, A., & West, C. P. (2014). Hospitalist career decisions among internal medicine residents. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 29, 1026–1030.

Roberts, J. K., Hargett, C. W., Nagler, A., Jakoi, E., & Lehrich, R. W. (2015). Exploring student preferences with a Q-sort: The development of an individualized renal physiology curriculum. Advances in Physiology Education, 39(3), 149–157.

Roberts, J. K., Sparks, M. A., & Lehrich, R. W. (2016). Medical student attitudes toward kidney physiology and nephrology: A qualitative study. Renal Failure, 38(10), 1683–1693.

Rosenthal, M. P., Diamond, J. J., Rabinowitz, H. K., et al. (1994). Influence of income, hours worked, and loan repayment on medical students’ decision to pursue a primary care career. JAMA, 271, 914–917.

Sivey, P., Scott, A., Witt, J., Joyce, C., & Humphreys, J. (2012). Junior doctors’ preferences for specialty choice. Journal of Health Economics, 31, 813–823.

Valenta, A. L., & Wigger, U. (1997). Q-methodology: Definition and application in health care informatics. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 4(6), 501–510.

Watts, S., & Stenner, P. (2012). Doing Q methodological research: Theory, Method, and Interpretation. Sage Publications.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

West, C. P., Drefahl, M. M., Popkave, C., & Kolars, J. C. (2009). Internal medicine resident self-report of factors associated with career decisions. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 24, 946–949.

West, C. P., & Dupras, D. M. (2012). General medicine vs. subspecialty career plans among internal medicine residents. JAMA, 308, 2241–2247.

West, C. P., Popkave, C., Schultz, H., Weinberger, S. E., & Kolars, J. C. (2006). Changes in career decisions of internal medicine residents during training. Annals of Internal Medicine, 145, 774–779.

Yang, J., Singhal, S., Weng, Y., et al. (2020). Timing and predictors of subspecialty career choice among internal medicine residents: A retrospective cohort study. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 12, 212–216.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge Dr. Vijay Daniels for giving permission to include existing Q-sort statements into the statement set used in this study. We also acknowledge the Internal Medicine program leadership at each training program that participated in this study. The authors also acknowledge the American Society of Nephrology and the William and Sandra Bennett Clinical Scholars Program, who supported this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed substantially to the design, recruitment, and implementation of the study. The authors also substantially contributed to the interpretation of data as well as review and approval of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

10459_2022_10172_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Supplemental Figure 1: Study Flow Diagram. Sequence of steps used to perform the Q-sort study. The figure includes a sample score sheet with forced distribution. (PDF 405 kb)

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Roberts, J.K., Schub, M., Singhal, S. et al. Exploring US internal medicine resident career preferences: a Q-methodology study. Adv in Health Sci Educ 28, 669–686 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-022-10172-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-022-10172-0