Abstract

Aim

One of the public health objectives of the Swedish and Danish alcohol policies is to reduce harm to individuals from the risky consumption of alcohol. In furtherance of this objective, it is interesting to research the purchasing and consumption patterns of drinkers, with a particular focus on clarifying the purchasing behavior of heavy drinkers relative to moderate and light drinkers. Thus, this article examines demand for alcoholic beverages in Denmark and Sweden.

Subjects and methods

Since there are significant differences in alcohol policy in Denmark and Sweden, it is interesting to study a comparative analysis of consumer behavior. Our study included a randomly drawn sample of the alcohol-buying population in both countries. A proportional odds model was applied to capture the natural ordering of dependent variables and any inherent nonlinearities.

Results

The findings show that individual demand for alcoholic beverages depends on economic, regional, and socio-demographic variables but that there is also a heterogeneity in consumer response to alcohol consumption under competition and monopoly.

Conclusion

This study provides some evidence and support to the notion that people can generally be characterized by certain factors associated with alcohol demand. This information can help policymakers when they discuss concepts related to public health issues.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The aim of this study is to estimate the determinants of individual demand for alcoholic beverages in Sweden and Denmark. According to the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs in Sweden, the aim of the Swedish alcohol policy is to reduce the total consumption of alcohol to alleviate the medical and social damage caused by alcoholic beverages. Swedish alcohol policy follows the total consumption model, formulated by the World Health Organization (WHO), which is the basis of the European region’s plan of action for reducing alcohol consumption. The total consumption model assumes a correlation between total alcohol consumption in a country and the damage caused by alcohol.

Sweden’s most important means of limiting availability are the alcohol monopoly and the price instrument. Like many other products, alcoholic beverages are sensitive to price. Thus, Sweden has been pursuing a policy of high alcohol taxes for many years. Since July 1, 1992, the tax on alcohol has been determined exclusively by the alcoholic content of the beverage. Furthermore, Swedish alcohol policy provides some additional measures such as restrictions on private imports, rules governing licensing permits for restaurants, age limits for purchasing alcohol, controlling marketing and sales, limiting private profit-making interests, and provision of information about the harmful effects of alcohol.

The availability of alcohol has increased over time in terms of the number of licenses (Swedish Council for Information on Alcohol and Other Drugs 2017). The price of alcohol has always varied, but retail prices have risen especially in the past few years. Men drink more alcohol than women, but over time, the difference between men’s and women’s self-reported alcohol consumption has narrowed. In recent years, nearly 6% of the Swedish population are estimated to have developed either alcohol abuse or dependency. Among adults in Sweden, however, total alcohol consumption is under the European average (Swedish Council for Information on Alcohol and Other Drugs 2017).

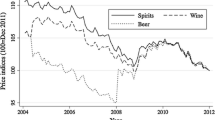

There are significant differences in alcohol policies in Denmark and Sweden. The Danish alcohol policy is more liberal than the Swedish one, without any state-owned, off-premise retail alcohol monopoly. In Sweden, the minimum legal age for purchasing all alcoholic beverages is 20 years, while in Denmark it is 16 years for purchasing wine and beer and 18 for strong alcoholic beverages. In comparison, taxation is much lower in Denmark than Sweden. In Denmark, the tax rate is 20.1%, 14.2%, and 7.5% for spirits, wine, and beer, respectively, while in Sweden it is 53.9%, 24.8%, and 21.1% for spirits, wine, and beer, respectively.

Furthermore, Denmark has the lowest prices for alcoholic beverages of all the Nordic countries. In Denmark and Sweden, the total alcohol consumption was about 10.2 l and 9.0 l per adult population, respectively, in 2016 (Penttilä and Österberg 2017). In Sweden, advertising of alcoholic beverages is only allowed for those which are at most 15% by volume, and the content of the advertisements is restricted. It is forbidden by law to advertise alcohol on the radio or television. In Denmark, advertising of alcoholic beverages is mostly regulated by voluntary agreements (Penttilä and Österberg 2017).

Previous studies on demand for alcohol have been influenced by a number of factors such as price, income, advertising, licensing restrictions, and social and legal factors, among others (Berggren 1997; Cook and Moore 2001; Saffer and Dave 2006; Gallet 2007; Wagenaar et al. 2009; Saffer et al. 2016). With respect to price, the existing literature clearly indicates that the demand curve for alcoholic beverages (beer, wine, and spirits), both individually and as a whole, slopes downward and that demand for alcohol is relatively inelastic, at −0.5. Previous studies also show that heavy drinkers are more responsive to advertising and less responsive to price than are moderate or light drinkers.

Studies comparing the prevalence of heavier or moderate and light drinking have produced mixed findings. Most alcohol demand studies have been conducted either by time-series analysis or used a cross-sectional approach and were based on evidence from the UK, Russia, Australia, and the US. Furthermore, with a few exceptions, they did not consider any nonlinearities in their estimations. To the best of the author’s knowledge, there has not been any econometric study of demand for alcohol in Sweden and Denmark. This article aimed to fill these gaps by modeling the Swedish and Danish alcohol market to explore differences in alcohol control policy. A proportional odds model (POM) was used here, which appropriately captures the natural ordering of dependent variables and any inherent nonlinearities (Agresti 2007). The article is organized as follows. The next section describes theoretical considerations and research questions; then data and methodology are introduced. The fourth section presents estimation results and a discussion, followed by a summary and the conclusion.

Theoretical considerations and research questions

Multiple factors influence alcohol demand. The most important variables cited in the literature are as follows.

Income

Because alcohol is usually considered a normal good, income is a relevant explanatory variable. Several studies show that there is a positive income elasticity of demand for alcohol. For example, Gallet (2007) reports an income elasticity for all alcoholic beverages of 0.50, meaning that a 1% increase in consumer incomes leads to a 0.5% increase in alcohol consumption. Lifetime patterns of income may be an important driver of alcohol use.

Cerdá et al. (2011) studied the relationship between long- and short-term measures of income and the relative odds of abstaining, drinking lightly/moderately, and drinking heavily. They utilized data from the US panel study on income dynamics, a national population-based cohort that has been followed annually or biannually since 1968. They examined 3111 adult respondents aged 30–44 in 1997. Their multinomial generalized logit models estimated the odds of abstinence or heavy drinking relative to light/moderate drinking. They found that lower income was associated with higher odds of abstinence and of heavy drinking relative to light/moderate drinking. For example, belonging to a household with a stable low income ($11,000–20,000) over 30 years was associated with 1.57 odds of abstinence and 2.14 odds of heavy drinking in adulthood. The association between lifetime income patterns and alcohol use decreased in magnitude and became non-significant once it was controlled for past-year income, education, and occupation.

Research has revealed that while lower-income individuals are at higher risk of engaging in heavy, hazardous drinking (Batty et al. 2008; Huckle et al. 2010), higher income is correlated with a higher frequency of light drinking (Ziebarth and Grabka 2009; Huckle et al. 2010). Disproportionate engagement in heavy drinking among lower-income individuals may be due to the notion of “self-medication,” whereby individuals exposed to higher levels of stress use alcohol as a way to relieve stressful life experiences or to alleviate strain (Boardman et al. 2001).

Hu and Stowe (2013) considered income as a budget constraint of the present as well as a component of future utility and found that those with lower incomes discounted future utility more heavily. They utilized data from the US and a multinomial logit method to assess two drinking behaviors, namely frequency of alcohol consumption and frequency of excessive alcohol consumption. Their results indicate that alcohol consumption frequency positively correlates with income, but that excessive alcohol use mostly takes place among the lower-income population. Such findings give support to the hypothesis that low-income individuals are more likely to make poor choices with regard to future health, since they discount future utility relatively heavily. However, with rising income the variety of other affordable options increases as well. Therefore, increasing opportunity costs of drinking alcohol, due to its harmful effect, may lead to a reduction in consumption.

Education

Several studies have identified the important role of education in explaining alcohol consumption. That is, more education is associated with more modest drinking behavior. Crum et al. (1993a, 1993b) found that individuals who had dropped out of high school were 6.34 times more likely to develop alcohol abuse or dependency than were individuals with a college degree; for those who had entered college but failed to achieve a degree, the estimated relative risk was 3.01 higher.

Droomers et al. (1999) concluded that excessive alcohol consumption was more common among lower educational groups in The Netherlands. Huerta and Borgonovi (2010) examined whether the probability of abusing alcohol differed across educational groups. They utilized data from the UK and found that higher educational attainment was associated with increased odds of daily alcohol consumption and problem drinking. Johnson et al. (2011) also reported that average drinking levels were highest among the most educated in Denmark.

Assari and Moghani Lankarani (2016) explored the idea that education is positively associated with ever drinking in the US. However, they found that race interacted with education level to influence drinking, suggesting a smaller effect of education on drinking for blacks than whites (Assari and Moghani Lankarani 2016). Drinking patterns and drinking outcomes were both shaped by an individual’s socioeconomic status, which determined patterns and frequency of alcohol use. While inconsistent findings have been reported, Brinkley (1999) found that moderate drinkers tend to enjoy higher socioeconomic status and suffer less frequently from alcohol-related problems.

Word-of-mouth/advertising

Word of mouth (WOM) has been shown to have a significant effect on alcohol consumption. It has been argued that WOM can be a credible means to share information about good and bad alcoholic beverages. Changes in the alcohol consumption behavior of an individual’s social network in turn have a statistically significant effect on their subsequent alcohol consumption behavior (Rosenquist et al. 2010). Based on behavioral economic theory, Saffer et al. (2016) reported that advertising has a small positive effect on consumption and that this effect is relatively larger at high consumption levels in the US. Nelson and Young (2001) studied a number of Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development countries over the period 1970–1990 and found a positive effect for advertising bans on alcohol consumption.

Snyder et al. (2006) showed that for every 4% more alcohol advertisements, 1% more drinks were consumed per month, and for every 15% more exposure in media markets to alcohol advertising, 3% more drinks were consumed per month in the US. It has also been found that exposure to some types of alcohol advertising on TV, in newspapers and magazines, on the internet, and on billboards/posters and promotional materials in bottle shops, bars, and pubs is associated with increased alcohol consumption (Jones and Magee 2011).

Age

Older individuals are more likely than younger ones to be abstainers, and the percentages of heavier drinkers and problem drinkers are higher among the young than older people (Higuchi et al. 1994). Research in the US found that alcohol consumption decreased with age (Kerr et al. 2002). A study from Great Britain also reported that mean consumption rose sharply during adolescence, peaked at around 25 years, and then declined and stabilized during mid-life, before declining from around 60 years onwards (Britton et al. 2015). This implies that willingness to consume alcohol subsides at an increasing rate as reported age advances.

Gender

It is widely known that gender has an impact on alcohol consumption. Drinking per se and high-volume drinking are consistently more prevalent among men than among women, and lifetime abstention from alcohol is consistently more widespread among women (Parry et al. 2005; Wilsnack et al. 2009). Schulte et al. (2009) explained the reasons for this different behavior and observed that physiological and social changes, particularly in adolescence, appear to differentially impact boys and girls as they transition into adulthood. They also revealed that boys begin to manifest a constellation of factors that put them at greater risk for disruptive drinking, such as low response to alcohol, later maturation in brain structures and executive function, greater estimates of perceived peer alcohol use, and socialization into traditional gender roles.

Nolen-Hoeksema and Hilt (2006) showed that although the same risk factors may be in place for men and women, men were more likely to exhibit the endogenous vulnerabilities and exogenous risks that increase their likelihood of meeting criteria for an alcohol use disorder (AUD). Furthermore, they pointed out that women’s physiological sensitivity to lower doses of alcohol, their experience of greater social sanctions against drinking, and increased risk for physical and sexual assault resulting from alcohol consumption constitute factors which prevent female drinkers from engaging in heavier alcohol use.

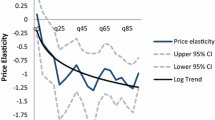

Willingness to pay

Studies have concluded that increases in the price of alcoholic beverages disproportionately reduce alcohol consumption among young people and also have a greater impact in terms of alcohol intake on more frequent and heavier drinkers than on less frequent and lighter drinkers (Anderson and Baumberg 2006). Gallet (2007) found a long- and short-term own price elasticity of −0.82 and − 0.5 for all alcoholic beverages, respectively. Akerlof (1970) discussed issues that arise because of asymmetric information possessed by the buyer and the seller of a product regarding its value. In many markets, sellers of a product are better informed about the good’s quality than buyers, resulting in the well-known “lemon” problem, whereby, since it is impossible for many consumers to distinguish high from low quality, goods of each type sell for the same price.

A growing body of literature has shown that the lemon problem is an important issue for experience and credence goods for which quality cannot be ascertained before consumption. However, producers can signal quality, and high quality can be signaled by advertising (Milgrom and Roberts 1986). One behavioral explanation, supported by empirical evidence, suggests that consumers infer information, such as quality, from price (Rao and Monroe 1988; Stiving 2000). Consequently, price appears to play two opposing roles, allocative and informational, in consumer demand, whereby higher price decreases consumer utility, because they must pay more for the product, but higher price may also create higher quality perceptions, which in turn increase utility. Intuitively, this complex relationship may lead to a non-monotonous (individual) utility function over price, which should then induce an (aggregate) demand function that is not necessarily downward sloped, as assumed ubiquitously in the literature. As a result, consumers may be willing to pay more than the original price if they perceive that their utilities are still increasing. Therefore, a nonlinear relationship would realistically account for the effects of price on demand.

Marital status

Prior studies have documented an association between marriage and lower alcohol consumption (Leonard and Rothbard 1999). For example, a general population survey of Swedish young adults showed that the frequency and quantity of alcohol consumption among married individuals were 41% and 51% lower than among single individuals (Plant et al. 2008). In an epidemiological study of Stockholm county, Halldin (1984) found a diagnosis of alcoholism was 2.1 times more common in single compared with cohabiting adults. This robust association was also confirmed by Kendler et al. (2016), who used Cox proportional hazard methods to estimate the risk of onset of AUD as a function of marital status and established the protective effects of marriage on the risk of alcoholism.

Rural-urban differences

Regional differences, i.e., conditions in urban versus rural areas in terms of availability and price of alcoholic drinks and closeness to other neighboring countries, can, among other things, influence alcohol consumption and/or drinkers’ perceptions of alcohol use. Bränström and Andreasson (2008) concluded that high alcohol consumption was more prevalent in those parts of Sweden that are closer to the European continent and that this might be an effect of the proximity to other European countries with lower prices for alcohol, less strict alcohol control policies, and higher availability of alcoholic drinks. Both the perceived and actual availability of alcohol from formal and informal sources can affect the prevalence of drinking (Treno et al. 2008).

According to an Australian report (Victorian Health Promotion Foundation 2017), the most important factors regarding regional differences are acceptability of intoxication (i.e., is it generally considered acceptable to be affected by alcohol?), affordability, and accessibility. The report also mentions that lack of adequate public transport in rural areas and work obligations (for example, the requirement to get up early the next day to work on the farm) are seen to limit drinking.

Dawson et al. (2011) suggested that prevalence rates of past-year drinking in the adult population were higher for urban residents compared with rural ones. Community disorder more generally, defined by population density, crime, etc., is positively associated with alcohol use in adolescents and adults (Bryden et al. 2013). Another strand of the literature has revealed that alcohol consumption is higher in rural areas than urban areas, especially in the US and Australia (Borders and Booth 2007; Chan et al. 2016). Studies comparing the prevalence of heavier or moderate and light drinking based on a dichotomous urban/rural classification have produced mixed findings. In addition to population density and proximity to a metropolitan area, a number of social and cultural factors characterize urban and rural settings. These include religious and cultural practices, community and family relationships, economic conditions, the enforcement of alcohol laws, alcohol outlet density, and advertising, etc. (Dixon and Chartier 2016).

However, research on alcohol consumption associated with living in a rural versus urban setting is complicated by the varied systems used to classify geographic location. Studies comparing the prevalence of heavier or moderate and light drinking based on a dichotomous urban/rural classification have produced mixed findings. Some from the US and Australia have revealed that alcohol consumption is higher in rural than urban areas (Borders and Booth 2007). This may stem from the fact that the US and Australia have different geographical conditions and alcohol policies compared with Sweden and Denmark. In the US and Australia, lower-income populations are also exposed to excess risks related to the presence of greater concentrations of alcohol outlets in their communities. This is due to dynamic processes that shape urban retail markets, such as outlets being attracted to areas of higher population density because of increased demand, but being excluded from higher income areas because of land and structure rents (Morrison 2015). The other mechanism which may explain increased alcohol consumption in rural and remote areas is due to a range of factors specifically characteristic of rural areas in the US and Australia, including lack of venues for recreation, economic and employment disadvantage, and less access to healthcare professionals and alcohol treatment services (National Rural Health Alliance 2014).

Research questions

One important outcome associated with this study was to answer the following questions: Does WOM or advertising affect demand for alcohol? Is high income associated with high alcohol consumption? Are married individuals less likely to consume alcohol than single individuals? Do urban and rural differences, under monopoly, affect demand for alcohol more than free competition? Is age important in demand for alcohol? Are highly educated individuals more likely to consume alcohol than less well-educated individuals? How is alcohol demand related to an increase in age? Are men more likely to consume alcohol than women? Do individuals with more WTP represent monopoly alcohol markets? Does consumer response differ under competition and monopoly?

Data and methodology

In Sweden, the sample was drawn from individuals in the two biggest cities of Skåne County, namely Malmö and Helsingborg. Skåne’s population is 1.3 million, and it has a relatively high population density of 123 inhabitants per km2. In Denmark, the sample was drawn from the Greve municipality, which is located southwest of Copenhagen. The municipality covers an area of 60 km2 and has a total population of around 50,000. The data for variables were collected from responses to a questionnaire which was distributed manually during June and July 2017 in Sweden and during December 2017 in Denmark.

In Sweden, a number of Systembolaget (alcohol shops which are a government-owned chain of alcohol stores and the only retail stores allowed to sell alcoholic beverages) were selected in the sample cities. A systematic stochastic sample of 190 individuals was chosen from outside these shops. Statistics Sweden does not make any distinction between rural and sparsely populated areas—it simply delimits built-up areas with a population > 200. By that definition, 16% of the population lives in rural areas, a level that has remained largely unchanged since about 1970. In the present study, rural areas are defined as those areas where there are no alcohol shops (Systembolaget) to buy alcoholic beverages and which are located outside the municipalities of Malmö and Helsingborg. In the case of Denmark, rural areas are defined as those with a population < 200, and one of the most popular chain stores named Bilka Hundige was selected. A systematic stochastic sample of 95 individuals was chosen from inside of these shops. The questionnaire was distributed to randomly selected individuals who were buying alcoholic beverage. To maintain anonymity, a box was placed in the location and respondents were asked to put their filled questionnaires into it.

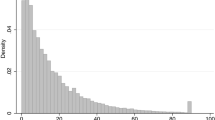

Regional, economic, and socio-demographic characteristics were included in the questionnaire. The observations on our dependent variable took three different forms: individuals with light alcohol consumption (LAC), individuals with moderate alcohol consumption (MAC), and individuals with heavy alcohol consumption (HAC). LAC, MAC, and HAC were defined as drinkers who drank one drink or less, two drinks, and three drinks or more per day, respectively.

Independent variables

The independent variables were as follows. Income (1 if earnings were > 25,000 Swedish Kronor or 2500 euros per month, 0 otherwise); level of education (1 for completion of higher studies, 0 otherwise); age, age square, which measured any nonlinearities; gender (1 if the respondent was male, 0 otherwise); marital status (1 if respondents were married legally or de facto, 0 otherwise); WOM (in the case of Sweden) and advertising (in the case of Denmark), regarding a specific alcoholic beverage (1 if the respondent paid attention to it when deciding to buy, 0 otherwise); WTP, which showed an individual’s willingness to pay more than the original price for an alcoholic beverage; WTP square, which measured any nonlinearities; and rural-urban differences (1 if respondent lived in an urban or suburban area, 0 otherwise). Appendix 1 shows the percentage distribution of the variables and the correlation matrix for the explanatory variables in Denmark and Sweden.

Estimation strategy

Ordered response variables are very common in social science research. In the 1980s and 1990s, methods such as ordinal logistic regression gained popularity, and researchers would often estimate models with ordinal dependent variables using ordinary least squares (OLS) regression. However, the unrealistic assumption of equal spacing between the categories of ordinal variables (e.g., Likert scales numbered 1–5) and the potential for misleading results eventually caused researchers to consider methods designed explicitly for ordinal outcomes (Long 1997). POMs are appropriate when the ordinal categorical responses are treated as ordinal categorical variables and the frequencies of the categories of the responses are of interest (McCullagh 1980). Another advantage of POMs is invariance to selection of the response categories (Agresti 2007). This implies that when the nine categories and three categories which were collapsed from the nine categories are used in parallel, similar conclusions will be reached (Agresti 2007).

A POM is used here, too, which appropriately captures the natural ordering of dependent variables and any inherent nonlinearities (Agresti 2007). This means that not only is the effect of a regressor non-constant on the probability of a given attitude, but its influence also varies across different attitudes. This model, which is based on a constrained ordinal model, has better statistical power than simple logistic regression (Capuano 2012). Furthermore, since our response, i.e., the observations on our dependent variable, was a three-level ordinal variable, it was wise to consider the natural ordering to the response levels when modeling the effects of the explanatory variables on consumer behavior (Agresti 2007). Appendix 2 provides a description of the POM in more detail.

Estimation results

Tables 1 and 2 show the relative importance of the explanatory variables described earlier. In Sweden, all variables were found to be statistically significant at conventional levels with expected signs except WOM/advertising, which was not significant. In Denmark, all variables were statistically significant at conventional levels with excepted signs except rural-urban differences, WTP, education, and income. The likelihood of being a heavy drinker depended on age. Thus, young individuals were more likely to be heavy drinkers, although the effect was nonlinear. This implies that drinking decreases at an increasing rate as age increases. The influence of marriage decreases the likelihood of being a heavy drinker. Having a university education decreases the likelihood of being a heavy drinker in Sweden, but not in Denmark, where a university education increases the likelihood of being a heavy drinker. Also, having a high income decreases the likelihood of being a heavy drinker in Sweden, but not in Denmark, where having a high income increases the likelihood of being a heavy drinker.

The probability of being a heavy versus a moderate or low drinker was also determined by gender. Being male increased the probability of being a heavy drinker. The likelihood of being a heavy drinker was also determined by WOM/advertising, but the effect was not significant in Sweden and only advertising was significant in Denmark. WTP was positive and significant in Sweden, showing that alcohol consumers were willing to pay more than the original price, although the effect was nonlinear. WTP was positive, but not significant, in Denmark. The table also shows alcohol use patterns among rural and urban residents. The likelihood of being a heavy drinker versus a moderate or low drinker was higher in urban than rural areas for Sweden, but this was not the case for Denmark, where the variable was not statistically significant.

Note that Tables 1 and 2 also show odds ratios. For example, in Sweden, in the case of rural-urban differences, the estimated odds ratio of being a heavy versus moderate or low alcohol drinker was 3.364, with lower and upper 95% confidence limits of 1.33 and 9.25, respectively. We performed a score test as a check for the proportional odds assumption. The resulting p value was 0.5590 for Sweden and 0.4350 for Denmark, implying that we cannot reject the null hypothesis of the proportional odds assumption. We also carried out a check for predictive power with a concordance index, indicating the probability of agreement between predicted probability and response. We found a value of 0.8971 for Sweden and 0.8159 for Denmark, both of which indicate a high predictive power.

Summary and conclusion

As shown earlier, the study of alcohol demand is multidisciplinary. The general consensus among researchers shows that future studies devoted to the investigation of the effects of issues related to alcohol demand should use a combination of demographic, socioeconomic, regional, and family situation aspects. Results can then be used to develop a model for understanding the important factors affecting the demand for alcohol. In practice, researchers require reliable and accurate information about ways that can be used to characterize individuals in their demand for alcohol. Any additional study that can provide a broader perspective regarding individual demand for alcohol contributes to the tools and techniques that policymakers can use when working with alcohol policy issues.

This study examined the determinants of individual demand for alcoholic beverages in Denmark and Sweden. Since there are significant differences in alcohol policy in the two countries—Denmark has a more liberal alcohol policy, while Sweden has a state-owned monopoly—it was interesting to study a comparative analysis of consumer behavior. The novel contribution of this study stems from the methodology it used, which took into account any nonlinearities in household alcohol purchases.

Based on the estimation of a POM, our results indicate that the probability of being a heavy alcohol consumer is affected by rural-urban differences, marital status, age, income, gender, WTP, WOM or advertising, and education, but that there is a heterogeneity in consumers’ response to alcohol consumption under competition and monopoly. These differences stem mainly from the fact that Denmark has a more liberal alcohol policy, with higher availability of alcoholic beverages and much lower alcohol prices compared with Sweden and that there is no advertising ban in Denmark.

The fact that demand for alcohol is correlated with regional, economic, and socio-demographic variables has important implications for theoretical and empirical research in regional economics. Results from this study provide some evidence and support to the notion that people can generally be characterized by certain factors associated with alcohol demand. This information can help policymakers when discussing concepts related to demand for alcohol. There are a few limitations inherent in this study. First, the survey relies on self-report data and there might have been under-reporting or underestimating of alcohol consumption due to social desirability; second, the sample only consisted of people who were buying alcoholic beverages from Systembolaget and Bilka Hundige and therefore could not take into account those who were buying alcoholic beverages from other sources.

References

Agresti A (2007) An introduction to categorical data analysis, 2nd edn. John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY

Akerlof GA (1970) The market for lemons: quality uncertainty and the market mechanism. Q J Econ 84(3):488–500

Anderson P, Baumberg B (2006) Alcohol in Europe: a public health perspective. London: Institute of Alcohol Studies. European Commission (OIL), Luxembourg, ISBN 92-79-02241-5

Assari S, Moghani Lankarani M (2016) Education and alcohol consumption among older Americans; black-white differences. Front Public Health 4:67

Batty GD, Lewars H, Emslie C, Benzeval M, Hunt K (2008) Problem drinking and exceeding guidelines for 'sensible' alcohol consumption in Scottish men: associations with life course socioeconomic disadvantage in a population-based cohort study. BMC Public Health 8:302

Berggren F (1997) Essays on the demand for alcohol in Sweden: review and applied demand studies, Lund Economic Studies no. 71., Lund University

Boardman JD, Finch BK, Ellison CG, Williams DR, Jackson JS (2001) Neighborhood disadvantage, stress, and drug use among adults. J Health Soc Behav 42(2):151–165

Borders TF, Booth BM (2007) Rural, suburban, and urban variations in alcohol consumption in the United States: findings from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. J Rural Health 23(4):314–321

Bränström R, Andréasson S (2008) Regional differences in alcohol consumption, alcohol addiction and drug use among Swedish adults. Scand J Public Healt 36(5):493–503

Brinkley GL (1999) The causal relationship between socioeconomic factors and alcohol consumption: a Granger-causality time series analysis, 1950-1993. J Stud Alcohol 60:759–768

Britton A, Ben-Shlomo Y, Benzeval M, Ku D, Bell S (2015) Life course trajectories of alcohol consumption in the United Kingdom using longitudinal data from nine cohort studies. BMC Med 13:47

Bryden A, Roberts B, Petticrew M, McKee M (2013) A systematic review of the influence of community level social factors on alcohol use. Health Place 21:70–85

Capuano AW (2012) Constrained ordinal models with application in occupational and environments health. Ph.D dissertation, University of Iowa

Cerdá M, Johnson-Lawrence VD, Galea S (2011) Lifetime income patterns and alcohol consumption: investigating the association between long- and short-term income trajectories and drinking. Soc Sci Med 73(8):1178–1185

Chan CK, Leung J, Quinn C, Kelly AB, Connor JP, Weier M, Hall WD (2016) Rural and urban differences in adolescent alcohol use, alcohol supply, and parental drinking. J Rural Health 32(3):280–286

Cook P, Moore M (2001) Environment and persistence in youthful drinking patterns. In: Gruber J (ed) Risky behavior among youths: an economic analysis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 375–337

Crum RM, Helzer JE, Anthony JC (1993a) Level of education and alcohol abuse and dependence in adulthood: a further inquiry. Am J Public Health 83(6):830–837

Crum RM, Anthony JC, Bassett SS, Folstein MF (1993b) Population-based norms for the mini-mental state examination by age and educational level. JAMA 12 269(18):2386–2391

Dawson DA, Hingson RW, Grant BF (2011) Epidemiology of alcohol use, abuse and dependence. In: Tsuang MT, Tohen M, Jones PB (eds) textbook in psychiatric epidemiology, 3rd edn. Wiley, Chichester

Dixon MA, Chartier KG (2016) Alcohol use patterns among urban and rural residents’ demographic and social influences. Alcohol Res 38(1):69–77

Droomers M, Schrijvers CT, Stronks K, van de Mheen D, Mackenbach JP (1999) Educational differences in excessive alcohol consumption: the role of psychosocial and material stressors. Prev Med 29(1):1–10

Gallet CA (2007) The demand for alcohol: a meta-analysis of elasticities. The Aust J Agric Resour Econ 51(2):121–135

Halldin J (1984) Prevalence of mental disorder in an urban population in central Sweden with a follow up of mortality. Thesis. Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden, Stockholm

Higuchi S, Parrish KM, Dufour MC, Towle LH, Harford TC (1994) Relationship between age and drinking patterns and drinking problems among Japanese, Japanese-Americans, and Caucasians. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 18(2):305–310

Hu X, Stowe CJ (2013) The effect of income on health choices: physical activity and alcohol use, 2013 annual meeting, August 4-6, Washington, DC 149616. Agricultural and Applied Economics Association, Washington DC

Huckle T, Quan You R, Casswell S (2010) Socio-economic status predicts drinking patterns but not alcohol-related consequences independently. Addiction 105(7):1192–1202

Huerta MC, Borgonovi F (2010) Education, alcohol use and abuse among young adults in Britain. Soc Sci Med 71(1):143–151

Johnson W, Kyvik KO, Mortensen EL, Skytthe A, Battylan GD, Deary J (2011) Does education confer a culture of healthy behavior? Smoking and drinking patterns in Danish twins. Am J Epidemio 173(1):55–63

Jones SC, Magee CA (2011) Exposure to alcohol advertising and alcohol consumption among Australian adolescents. Alcohol and Alcoholism 46(5):630–637

Kendler KS, Larsson Lönn S, Salvatore J, Sundquist J, Sundquist K (2016) Effect of marriage on risk for onset of alcohol use disorder: a longitudinal and co-relative analysis in a Swedish national sample. Am J Psychiatry 173:911–918

Kerr WC, Fillmore KM, Bostrom A (2002) Stability of alcohol consumption over time: evidence from three longitudinal surveys from the United States. J Stud Alcohol 63:325–333

Leonard KE, Rothbard JC (1999) Alcohol and the marriage effect. J Stud Alcohol Suppl 13:139–146

Long JS (1997) Regression models for categorical and limited dependent variables. Thousand Oaks, CA

McCullagh P (1980) Regression models for ordinal data. J R Stat Soc B 42(2):109–142

Milgrom P, Roberts J (1986) Price and advertising signals of product quality. J Polit Econ 94(4):796–821

Morrison C (2015) Exposure to alcohol outlets in rural towns. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 39(1):73–78

National Rural Health Alliance (2014) Alcohol use in rural Australia, Victoria, Australia, Victoria

Nelson JP, Young DJ (2001) Do advertising bans work? An international comparison. Int J Advert 20(3):273–296

Nolen-Hoeksema S, Hilt L (2006) Possible contributors to the gender differences in alcohol use and problems. J Gen Psychol 133(4):357–374

Parry CDH, Plüddemann A, Steyn K, Bradshaw D, Norman R, Laubscher R (2005) Alcohol use in South Africa: findings from the first demographic and health survey (1998). J Stud Alcohol 66:91–97

Penttilä R, Österberg E (2017) Information on the Nordic alcohol market. National Institute for health and welfare (THL), Helsinki

Plant M, Miller P, Plant M, Kuntsche S, Gmel G, Ahlstrom S (2008) Marriage, cohabitation and alcohol consumption in young adults: an international exploration. J Subst Use 13(2):83–98

Rao AR, Monroe KB (1988) The moderating effect of prior knowledge on cue utilization in product evaluations. J Consum Res 15(2):253–264

Rosenquist JN, Murabito J, Fowler JH, Christakisa NA (2010) The spread of alcohol consumption behavior in a large social network. Ann Intern Med 152(7):426–433

Saffer H, Dave D (2006) Alcohol advertising and alcohol consumption by adolescents. Health Econ 15(6):617–637

Saffer H, Dave D, Grossman M (2016) A behavioral economic model of alcohol advertising and price. Health Econ 25(7):816–828

Schulte MT, Ramo D, Brown SA (2009) Gender differences in factors influencing alcohol use and drinking progression among adolescents. Clin Psychol Rev 29(6):535–547

Snyder LB, Milici FF, Slater M, Sun H, Strizhakova Y (2006) Effects of alcohol advertising exposure on drinking among youth. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 160(1):18–24

Stiving M (2000) Price-endings when prices signal quality. Manag Sci 46(12):1617–1629

The Swedish Council for Information on Alcohol and Other Drugs (2017) Alcohol consumption in Sweden. Stockholm, Sweden, Stockholm

Treno AJ, Ponicki WR, Remer LG, Gruenewald PJ (2008) Alcohol outlets, youth drinking, and self-reported ease of access to alcohol: a constraints and opportunities approach. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 32(8):1372–1379

Victoria Health Promotion Foundation (2017) Brief insights drinking cultures in rural and regional settings, generation X and baby boomers. Victoria, Australia, Victoria

Wagenaar AC, Salois MJ, Komro KA (2009) Effects of beverage alcohol price and tax levels on drinking: a meta-analysis of 1003 estimates from 112 studies. Addiction 104(2):179–190

Wilsnack RW, Wilsnack SC, Kristjanson AF, Vogeltanz-Holm ND, Gmel G (2009) Gender and alcohol consumption: patterns from the multinational GENACIS project. Addiction 104(9):1487–1500

Ziebarth N, Grabka M (2009) In vino Pecunia? The association between beverage-specific drinking behavior and wages. J Labor Res 30(3):219–244

Acknowledgments

I thank two anonymous referees for their comments. Any remaining errors are my responsibility.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval: Informed consent

Verbal consent was taken, i.e., the participants were verbally informed about the structure of the study and verbally agreed to participate. Information was presented to enable individuals to freely decide whether or not to participate in the process. The participants were informed about the study’s purpose and duration and assured of confidentiality and their right to withdraw from the study at any time.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Proportional odds model (POM)

Since our response, i.e., the observations on our dependent variable, was a three-level ordinal variable, it is wise to consider the natural ordering to the response levels when modeling the effects of the explanatory variables on consumer behavior (Agresti 2007). Let:

and

where π1(xi) is the probability of being a heavy alcohol consumer (HAC) at the ith setting of values of k explanatory variables xi = (x1i,..., xki), while π2(xi) and π3(xi) are the probabilities of being a moderate alcohol consumer (MAC) and being a low alcohol consumer (LAC), respectively. Thus, θ1(xi) and θ2(xi) represent cumulative probabilities: θ1(xi) is the probability of being an HAC, and θ2(xi) is the probability of being an MAC or even being an HAC. Let us define the two cumulative logits:

and

The first cumulative logit should be interpreted as the log odds of being an HAC compared with being an MAC or an LAC, and the second logit is the log odds of being an MAC or an HAC compared with an LAC. By assuming that the log odds are linear functions of the explanatory variables, we can write:

We maximized the log of the likelihood function to obtain maximum likelihood estimates:

subject to Eq, (5), where dhi = 1 if the ith individual gets the hth purchasing option i = 1, 2 …, n, h = 1, 2, 3 dhi = 0 otherwise.

However, this approach does not take into account the ordinal scale of the response variable. Thus, we suggest using the following, more parsimonious, model:

Hence, the effect of an explanatory variable on the log odds of being an HAC compared with being an MAC or LAC is the same as the log odds of being an MAC or HAC compared with being an LAC. Furthermore, to better grasp the consequences implied by the restriction, let x1 and x2 be two different settings of the explanatory variables. We then have the following result:

The log cumulative odds ratios are proportional to the distance between the values of the explanatory variables. This feature has also given the model its name as the POM model. However, maximizing the log of the likelihood function given by Eq. (6) subject to the constraints in Eq. (7) yields the parameter estimates of α1, α2, and β.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Irandoust, M. A non-linear approach to alcohol consumption decisions: monopoly versus competition. J Public Health (Berl.) 29, 1443–1453 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-020-01264-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-020-01264-5