Abstract

This study scrutinizes the ramifications of the strategic use of a consumer welfare argument in regulating foreign acquisitions and foreign market entry (i) on a multinational’s choice between acquiring a local firm’s existing assets (via negotiations or auctions) and investing in new assets via greenfield entry, or trade, under both complete and incomplete information; and (ii) on welfare. Any foreign acquisition fulfilling a minimum output requirement imposed by the host country as part of the foreign market entry regulation is in the best interest of the multinational even when there is complete trade liberalization. A local firm appropriates a bigger share from acquisition gains in an auction, and prefers generating information asymmetries. Welfare improves with a larger scope for ex-post firm heterogeneity when the foreign market entry regulation includes a minimum output requirement for foreign acquisitions based on consumer welfare.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Foreign direct investment (FDI) has been the driving force of the global economy since the 1980s, and mergers and acquisitions (acquisition of existing assets in host countries) have been the leading mode of FDI, especially in developed countries in the late 1990s.Footnote 1 There is now a large body of the literature analyzing (i) the gains from acquisition of existing assets and the merger paradox (e.g., Salant et al. 1983; Perry and Porter 1985; Deneckere and Davidson 1985; Farrell and Shapiro 1990; Lommerud and Sorgard 1997; Hennessy 2000); and (ii) the choice between partnership arrangements with local firms (joint ventures, mergers or acquisitions) and a wholly-owned subsidiary (greenfield investment in new assets) in foreign countries (e.g., Görg 2000; Bjorvatn 2004; Desai et al. 2004; Norbäck and Persson 2004, 2007; Müller 2007; Raff et al. 2006, 2009a, 2012; Qiu 2010; Fatica 2010; Qiu and Wang 2011).Footnote 2

Mergers and acquisitions are mostly subject to certain enforcement practices, which may confine their clearance to some performance measures, that is, only a subset of potentially profitable deals will be approved, which will change firm behavior and welfare. The literature focuses on aggregate surplus on this matter assuming that any firm acquisition would be approved by an antitrust authority so long as it did not decrease aggregate welfare. In most countries, however, antitrust authorities bring consumer welfare to the forefront. In New Zealand, for instance, mergers and acquisitions that lessen competition and adversely affect consumers are prohibited under the Commerce Act 1986.Footnote 3 Australia has a similar practice under the Competition and Consumer Act.Footnote 4 Similarly, enforcement practices in the US and the EU can be best approximated by a consumer-welfare standard (Breinlich et al. 2017). The implications of adopting a consumer-surplus standard on firm behavior and welfare have been delineated, to some extent, by the Industrial Organization (IO) literature. This literature focuses on competition policy practices, and thus on mergers and acquisitions between firms that are already competing in the same market and on the application of a consumer-welfare standard in approvals of domestic mergers or acquisitions; see, for example, Dertwinkel-Kalt and Wey (2016); Breinlich et al. (2015); Nocke and Whinston (2010); Goppelsroeder et al. (2008). A consumer welfare argument in the context of potential foreign market entry by a multinational (that is not yet in the market) is, however, overlooked especially by the trade and FDI literature. This study, thus, would like to make progress on this.

The main contribution of this study to the trade and FDI literature is that in a simple Cournot oligopoly model, it incorporates the strategic use of a consumer welfare argument into foreign market entry regulations and looks into potential foreign market entry by a multinational (either by greenfield investment/trade, or via foreign acquisition of a local firm) and its welfare implications. To this end, although the scope of the main (consumer welfare) argument is consistent with one as in the IO literature, it is not employed as a competition policy practice in this study, but rather it is determined as the outcome of negotiations for foreign market entry between the host country and the multinational; that is, it is geared especially toward regulating potential foreign market entry by a multinational. In the case of domestic acquisitions, any transfer of surplus among firms still contributes to total welfare, and thus a competition policy practice that secures a level of consumer welfare that is at least as good as the initial (pre-acquisition) market structure is sufficient from the host country perspective. This is not the case in the context of potential market entry by a multinational, which implies in most cases an increase in aggregate output (relative to the initial case with no market entry) and a decrease in local profits (as some surplus is transferred from local firms to the multinational), with an ambiguous impact on local welfare (assuming the multinational does not retain its profits in the host country). In particular, borrowing the idea from the IO literature, this study shows that by strategically using a consumer-surplus standard in regulating foreign market entry, the host country will not be worse-off, but can substantially gain in terms of local welfare.

The strategic use of a consumer-surplus standard (as the outcome of negotiations between the host country and the multinational) in regulating foreign market entry warrants a minimum output requirement for foreign acquisition of a local firm if the host country decides to allow for foreign market entry. Given the multinational is allowed to enter the market and required to not produce below a certain output level if its entry is via acquisition of a local firm (and given that there are two local firms, foreign acquisition of which will fulfill the minimum output requirement), in the first part of the study, under complete cost information, an investor’s firm selection for foreign acquisition and the acquisition price are endogenously determined in three different mechanisms: sequential offers, generalized Nash bargaining, and an ascending auction. In this regard, the first part of the study can be related to Norbäck and Persson (2008) and Pagnozzi and Rosato (2016). While Norbäck and Persson (2008) also focus on the choice between foreign acquisition and greenfield entry, potential implications of a foreign market entry regulation that includes a consumer welfare argument on multinational behavior and on local welfare are not studied. By the some token, in Pagnozzi and Rosato (2016), a foreign market entry regulation that includes a consumer welfare argument is not an issue, nor is the choice of a multinational between foreign acquisition and greenfield entry (or trade).

Considering no private cost information and no ex-ante significant cost asymmetry between local firms, but ex-post firm heterogeneity due to an efficient firm’s greenfield entry, or due to firm-specific synergies (if entry is by foreign acquisition), the first part of the study shows that some results suggested for domestic firm acquisitions by the IO literature, where a consumer-surplus standard is employed as a competition policy practice, can be extended also to foreign acquisitions, for which a consumer welfare argument is strategically used to regulate foreign market entry, such that (i) a minimum output requirement for foreign acquisition warranted by the strategic use of a consumer-surplus standard in regulating foreign market entry implies an upper-bound threshold of ex-post marginal production costs (similar to Farrell and Shapiro 1990; ii) irrespective of the method by which the multinational acquires existing assets of a local firm, the multinational prefers acquiring the firm that decreases ex-post marginal costs more (the ex-post efficient firm); and (iii) the multinational prefers sequential offers to an ascending auction under complete information, while the local firms’ profits (and thus welfare) are greater in an auction than in negotiations. An interesting result that provides an alternative explanation to an important observation is that if there is some potential foreign takeover that will fulfill the minimum output requirement of the foreign market entry regulation, then it is in the best interest of the multinational (more profitable than greenfield entry or trade) even under complete trade liberalization.

In the FDI literature, studies mostly rely on models with complete information. In cross-border investments, however, some firms are better informed than others. In the case of foreign acquisition of existing local assets, for instance, the majority of targets have been the firms that are not publicly listed (Ang and Kohers 2001; Draper and Paudyal 2006) resulting in information asymmetries that crucially affect multinationals’ investment strategies (Koska and Stähler 2014; Lópes Duarte and García-Canal 2004; García-Canal et al. 2002; Shen and Reuer 2005). To address this, the model is extended so as to take information asymmetries among firms on board. The second part of the study delineates the optimal foreign market entry choice of the multinational and scrutinizes welfare ramifications of strategically using a consumer-surplus standard in regulating foreign market entry under incomplete cost information such that firm-specific synergies (generated by foreign acquisition of a local firm’s existing assets) are private information. By extending the model to the case of information asymmetries in foreign takeovers with endogenous profit shares, the second part of the study also addresses the problem of identifying good matches with potential local targets. The second part of the study can be related, to some extent, to the literature on auctions with externalities. Koska et al. (2017), for instance, show that if the target firms are ex ante heterogeneous in their production costs that are their private information, then any auction mechanism that separates costs will lead to a commitment problem on the investor’s part. Jehiel and Moldovanu (2000) look at the sale of a cost-reducing innovation, which generates negative externalities on other firms, in a second-price, sealed-bid auction; and Goeree (2003) considers an auction setup for a cost-reducing patent, and finds an upward bias on the equilibrium bidding strategies, especially when bidders signal their private information via the winning bid. Ding et al. (2013), in a signaling model, compare different takeover auction mechanisms (e.g., first-price vs. second-price, cash vs. profit-sharing auction) that are followed by Cournot competition. Janssen and Karamychev (2010) consider after-market Cournot competition and look into auctioning of multiple licenses. They show that the auction mechanism does not always choose the most cost-efficient firms. The main focus in these studies is, however, exclusively on the optimal sale mechanism. That is, they do not look at the implications of a foreign market entry regulation that incorporates a consumer welfare argument on the conflict between the host country and the investor in terms of the preferred market entry mode.

The second part of the study further contributes to the trade and FDI literature by not only incorporating the consumer welfare argument into the host country’s foreign market entry regulation, but also by scrutinizing the multinational’s optimal foreign market entry mode and its welfare implications under incomplete cost information. The results suggest that, unlike the conventional wisdom, private information by local firms regarding the “quality of the match” (modeled as the size of the ex-post marginal production cost of a potential foreign takeover) need not bias the multinational’s choice toward greenfield investment, or trade, especially when there is a minimum output requirement in the case of acquisition of existing assets of a local firm. On the contrary, by auctioning off its participation to local firms, the multinational can identify the most profitable (ex-post efficient) local target firm and can gain from acquisition of that firm’s assets, insofar as acquisition of the local firm’s assets fulfills the minimum output requirement. Similar to the result from the first part of the study, also under incomplete information, the multinational prefers acquiring a local firm’s assets over greenfield entry or trade even in the times of complete trade liberalization. The welfare implications of such foreign takeovers depend on the spread of the distribution of ex-post productivity: local welfare improves (i) if the local firms have ex-ante sufficiently high marginal costs; (ii) if the expected contribution of acquisition of existing assets to the productivity of the multinational is sufficiently large; or (iii) if the expected negative impact of a foreign takeover on the other local rival is sufficiently small. If, however, the local firms have only a small productivity disadvantage relative to the multinational, foreign market entry can have detrimental effects on local welfare.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Sect. 2 first introduces the model with complete information and the minimum output requirement (based on consumer welfare) for foreign acquisition as the outcome of negotiations for foreign market entry between the host country and the multinational, then solves the model (i) for a subgame perfect Nash equilibrium in pure strategies for the case of sequential offers (Sect. 2.1), which is extended also to generalized Nash bargaining (“Appendix 1”); and (ii) for a pure-strategy equilibrium for the case of an ascending auction (Sect. 2.2). Section 3 extends the model to a private cost information structure and introduces a second-price, sealed-bid auction by which the investor’s share from acquisition profits is determined. In what follows, Sect. 4 scrutinizes the welfare implications of the strategic use of a consumer-surplus standard in regulating foreign market entry, and briefly discusses the policy implications of the model. Section 5 provides some extensions and discussions of the main argument for the case of complete trade liberalization and for potential buyer competition for foreign acquisition when the host country strategically uses a consumer welfare argument in regulating foreign market entry. Section 6 concludes. For convenience, most of the proofs and technical details are relegated to the “Appendix”.

2 The model

Consider a host country market that initially has two local firms: firms i and j. Entry to this market is restricted as in Norbäck and Persson (2008) and Koska et al. (2018). More specifically, similar to Koska et al. (2018), and following the stylized facts on multinationals such that their intangible assets enable them to penetrate oligopolistic markets, Z units of a specific factor are required to develop intangible assets within firm boundaries so as to be able to produce at all. The aggregate supply of this factor is assumed to be strictly less than 4Z and the outside option of this factor determines its wage, which is normalized to unity. Therefore, the model focuses on two local firms (already invested in the specific factor) and a potential entrant with its headquarters outside the host country (to avoid dissipation of its knowledge capital), namely the multinational firm. All firms are risk neutral and produce a homogeneous good. Note that investment in specific factor Z only makes the firms productive for the host country market, and thus fixed cost Z plays no role in determining the multinational’s foreign market entry mode.

Empirical evidence from various countries (documented largely by the empirical literature on firm heterogeneity that follows especially Helpman et al. 2004) shows that productivity differences among firms are mostly attributed to multinationality; e.g., see, among others, Castellani and Zanfei (2007) for evidence from Italian firms. Thus the local firms are assumed to have ex-ante identical marginal costs, denoted by \(c=c_{i}=c_{j}\in (0,1)\). Conditional on the host country allowing for foreign market entry, the MNF can invest in new assets (greenfield investment) in the host country, and can produce the homogeneous good with a lower marginal cost denoted by \(c^{*}\in (0,c)\).Footnote 5 Alternatively, the MNF can acquire existing assets of a local firm, which generates synergies and decreases marginal production costs. Let \(\theta _k\in [0,\overline{\theta }]\) denote the ex-post marginal cost of the MNF after having acquired existing assets of firm k, \(k\in \{i,j\}\). \(\overline{\theta }\) is the upper bound that is implied by a minimum output requirement for foreign acquisition warranted by the host country’s strategic use of a consumer welfare argument in regulating foreign market entry, that is, any foreign takeover that generates sufficient synergies such that \(\theta _k \le \overline{\theta }\), \(k\in \{i,j\}\) (so that the minimum output requirement is fulfilled) will be allowed by the host country; see Condition 1.Footnote 6

Consumers have quasilinear preferences such that the inverse demand function is given by \(P(Q)=\left( 1-Q\right)\), where P is the market price of the homogeneous good and Q stands for aggregate output. Total production (or sales) if the MNF undertakes greenfield FDI, \(Q^{g}=q^{g}_{m}+\sum _{k} q_k^{g}\), comprises the MNF’s output \(q^{g}_{m}\) and the local outputs \(\sum _k q_k^{g}\), \(k\in \{i,j\}\), where superscript g stands for greenfield, and subscript m represents the MNF. If the MNF enters the market by foreign acquisition, then there will be one less firm, in which case total sales, \(Q^{v}=q^{v}+q^{e}_{-k}\)—if firm k’s assets are acquired—will comprise the MNF’s output \(q^{v}\) and the non-acquired firm’s output \(q^{e}_{-k}\), \(k\in \{i,j\}\). Note that superscript v represents the new entity (after foreign acquisition takes place), and superscript e represents the non-acquired firm that will have to compete against the new entity.

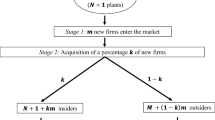

The MNF can acquire existing assets of a local firm either via negotiations or through an auction. In the case of negotiations with the local firms, the MNF can sequentially make take-it-or-leave-it offers to the local firms with the option to interrupt negotiations any time so as to opt for greenfield entry, and if both firms reject the offers that they receive, then the MNF enters the market via greenfield FDI.Footnote 7 An extensive form (a game tree) representation of sequential offers including the greenfield FDI option is given by Fig. 1 (Sect. 2.1), where \(\pi _{m}^{g}\) and \(\pi _{k}^{g}\), \(k\in \{i,j\}\), represent, respectively, the investor’s and the local firms’ profits when the MNF undertakes greenfield investment, and \(\pi _{m}^{v}, \pi _{k}^{v}\) and \(\pi _{-k}^{e}\) represent those when the MNF acquires firm k, \(k\in \{i,j\}\). The interaction between firms takes place such that (i) after having invested in specific factor Z, the MNF expresses its interest to enter the market and negotiates with the host country (the outcome of which will determine the minimum output requirement for foreign acquisition if the host country allows for foreign market entry); (ii) if the host country allows for foreign market entry, given the minimum output requirement for foreign acquisition, the MNF decides on its foreign market entry mode; (iii) finally, all active firms compete by quantities. The game is solved backwards.

In the last stage of the game (once the MNF’s entry mode is sorted), all active firms in the market engage in Cournot competition. Given the inverse demand function above, in a linear Cournot oligopoly model with n firms, each producing a homogeneous good with a constant marginal cost, each firm maximizes its profits, given by \(\pi _k(\cdot )=(p(Q)-c_k)q_k\), where \(k \in \{m,i,j\}\). Each firm’s Cournot–Nash equilibrium production can be represented by \(q^*_{k}=(1-nc_{k}+\sum \nolimits _{l\ne k}^{n}c_{l})/(n+1)\), where \(k,l \in \{m,i,j\}\), and \(\sum \nolimits _{l\ne k}^{n}c_{l}\) represents the sum of the marginal costs of all firms excluding firm k. In a Cournot–Nash equilibrium, the maximized firm profits are equal to \(\pi _k^*=-p^\prime (Q) (q^*_k)^2\), where \(p^\prime (Q)=-1\), and thus, \(\pi _k^*=(q^*_k)^2\), where \(k \in \{m,i,j\}\). It is straightforward to show that a firm produces and earns more with a decrease in its costs, while it produces and earns less with a decrease in its rivals’ costs. Also, an increase in the number firms competing in the market raises competition, with which the market price decreases (aggregate sales increase), although average firm size (i.e., the intensive margin) decreases.

When there is no investment (if the host country does not allow for foreign market entry), there will be only two local firms (\(n=2\)) that are symmetric in costs (c). Each local firm produces \(q^a_i=q^a_j=(1-c)/3\), where a represents the case of no investment. The MNF’s profit from the host country is \(\pi _{m}^{a}=0\), and the local Cournot duopoly profits are

The MNF can undertake greenfield investment by paying a fixed investment cost, which is, for the sake of simplicity and to save space in notation, normalized to zero: this implies that greenfield investment is profitable, and thus the MNF will always have a genuine interest in entering the market.Footnote 8 Greenfield investment earns the MNF \(\pi _{m}^{g}=(q^g_m)^2\), while the local firms earn \(\pi _{i}^{g}=(q^g_i)^2\) and \(\pi _{j}^{g}=(q^g_j)^2\) s.t.

Assuming \((1-2c+c^{*})>0\)—no crowding-out effect of greenfield investmentFootnote 9—relative to local duopoly, (i) competition raises with an increase in the number of firms by one; (ii) local firms’ sales and profits decrease (some surplus is transferred to the MNF); and (iii) the average industry marginal cost decreases, with which total industry output increases.

The MNF can enter the market also by acquiring existing assets of a local firm, which decreases competition (relative to greenfield entry) by decreasing the number of firms by one. Foreign acquisition, however, may generate synergies, such that the ex-post marginal cost of the MNF acquiring firm k will be \(\theta _k\), \(k\in \{i,j\}\). It is clear that, unless the ex-post marginal cost of the new entity is above the ex-ante marginal cost of the (replaced) acquired firm (assuming no spillover that may change the non-acquired firm’s ex-post marginal cost), compared to the initial local duopoly case, the average industry marginal cost decreases, with which total industry output increases. If such new market entry had been through domestic firm acquisition, then a consumer-surplus standard employed as a competition policy practice would have been already fulfilled under some positive efficiency gains from firm acquisition. The host country striving to increase aggregate local welfare, however, would need more than that provided by such a competition policy practice, especially in the case of foreign acquisitions. The reason is simple: in the case of domestic acquisitions, any transfer of surplus among firms still contributes to total welfare, and thus a competition policy practice that secures a level of consumer welfare that is at least as good as the initial (pre-acquisition) market structure is sufficient also from the host country perspective. By contrast, new market entry by foreign acquisitions, in most cases, leads to an increase in aggregate output (relative to the initial case with no market entry) and a decrease in local profits (as some surplus is transferred from local firms to the MNF), with an ambiguous impact on local welfare (assuming the MNF does not retain its profits in the host country).

Following the fact that multinationals do negotiate with host countries before their foreign market entry, and that certain production requirements can be imposed by host countries on foreign market entry, an alternative approach that is especially geared toward regulating potential investments by multinationals is proposed in this study: instead of employing a consumer-surplus standard as a competition policy practice, the host country can incorporate a consumer welfare argument into a foreign market entry regulation. In the first stage of the game, after having invested in a specific factor that makes itself productive for the market, the MNF expresses interest in entering the host country market. The host country asks the multinational to open its books which will reveal the particulars of its performance should it enter the host country market as a solo firm. Upon investigating the books, the host country can easily solve the firm problem backwards, and can either ban foreign market entry (especially if local welfare deteriorates), or can allow for foreign market entry and can require the MNF to commit to not produce below a certain output level in the case of market entry by foreign acquisition. By choosing the minimum output requirement as one that secures the same aggregate output as in the case of entry as a solo firm, the host country can make sure that it will not lose but can gain in terms of welfare: in the second stage of the game, (i) if there is no market entry by the MNF following their negotiations, the host country loses nothing (back to the benchmark case of local duopoly); (ii) if the MNF decides to undertake greenfield investment, then the host country gains in terms of consumer welfare (and given that foreign market entry is allowed based on its positive impact on overall local welfare, the host country gains also in terms of total welfare); or (iii) if there is foreign acquisition, which generates sufficient efficiency gains, and thus meets the host country’s minimum output requirement, then the host country can gain even further. These arguments are formalized in the rest of the paper.

The investor’s acquisition of existing assets of a local firm leads to Cournot duopoly between the MNF (the new entity) and the non-acquired local firm, the outcome of which is the new entity producing \(q^v=(1-2\theta _k +c)/3\) and the non-acquired local firm producing \(q^e_{-k}=(1-2c+\theta _k )/3\), where \(k\in \{i,j\}\) represents the acquired local firm. A minimum output requirement for foreign acquisition warranted by the strategic use of a consumer-surplus standard in regulating foreign market entry is, thus, given by

Condition 1

(Minimum output for foreign acquisition) With foreign acquisition, the MNF should commit to produce at least\(\bar{q}^v(\bar{\theta },c)\)such that\(Q^v(\bar{\theta },c)=Q^g(c,c,c^*)\), where\(\bar{\theta }= (2c+3c^*-1)/4\).

In this Cournot setting with constant marginal costs, Condition 1 puts an upper bound to the ex-post marginal cost of the new entity such that \(\theta _k\in [0,(2c+3c^*-1)/4]\), \(k\in \{i,j\}\), which is the necessary and the sufficient condition for \(Q^v\ge Q^g\). Intuitively, Condition 1 warrants that the negative effect of reduced competition (one rival less) on aggregate production should always be outweighed by the positive effect of increased competition caused by a more efficient new entity.

Firm profits when firm \(k\in \{i,j\}\) is acquired can be expressed as:

where the net return from acquisition of existing assets of firm \(k \in \{i,j\}\) to the MNF is \(\pi _{m}^{v}(\theta _k)=\pi ^{v}(\theta _{k})-\pi _{k}^{v}\), and to the acquired firm is \(\pi _{k}^{v}\), that is, the acquisition price determined endogenously.

2.1 Sequential offers for foreign acquisition

If the host country allows for foreign market entry in the first stage, then in the second stage, the MNF has to choose between greenfield investment and foreign acquisition (subject to the minimum output requirement given by Condition 1). Figure 1 depicts an extensive form game between the MNF and the local firms, where the MNF makes sequential offers to the local firms for potential foreign acquisition. The game is solved for a subgame perfect Nash equilibrium (SPNE).

In the last subgame (on the left) starting with firm j’s decision node, the MNF offers firm j its rejection profit (\(\pi _j^g\))—or rather, \(\lim _{\epsilon \rightarrow 0} \pi _j^g+\epsilon\)—which will be accepted by firm j. Offering firm j its rejection profit if firm i has rejected the MNF’s initial offer is individually rational for the MNF as \(\pi ^v(\theta _j)-\pi _j^g \ge \pi _m^g\) for any \(\theta _j \in [0,(2c+3c^*-1)/4]\). Therefore, if the MNF makes its initial offer to firm i, then this offer will be equal to firm i’s rejection profit \(\pi _i^e(\theta _j)\)—or rather, \(\lim _{\epsilon \rightarrow 0} \pi _i^e(\theta _j)+\epsilon\)—that is, the profit firm i would have earned by competing against the investor had the investor acquired firm j’s assets. Similarly, moving backwards from the last subgame (on the right) starting with firm i’s decision node, it can be shown that if the MNF makes its initial offer to firm j, then this offer will be equal to firm j’s rejection profit \(\pi _j^e(\theta _i)\)—or rather, \(\lim _{\epsilon \rightarrow 0} \pi _j^e(\theta _i)+\epsilon\)—that is, the profit firm j would have earned by competing against the investor had the investor acquired firm i’s assets. Therefore, the MNF can acquire firm k’s assets simply by offering the firm its rejection profit \(\pi _k^e(\theta _{-k})\), \(k\in \{i,j\}\). Note that \(\pi _k^g \ge \pi _k^e(\theta _{-k})\) for any \(\theta _{-k}\in [0,(2c+3c^*-1)/4]\), \(k\in \{i,j\}\), that is,

Lemma 1

(Rejection profits) A minimum output requirement for foreign acquisition generates a credible threat on the local firms and decreases the potential acquisition price by reducing their rejection profits.

Which local firm should the investor target and make the initial offer? Which entry mode is optimal for the MNF? If the MNF makes the initial offer to firm i, then it pays \(\pi _i^e(\theta _j)\) and acquires firm i’s assets, and earns \(\pi ^v(\theta _i)-\pi _i^e(\theta _j)\). If, however, it makes the initial offer to firm j, then it pays \(\pi _j^e(\theta _i)\) and acquires firm j’s assets, and earns \(\pi ^v(\theta _j)-\pi _j^e(\theta _i)\). The equilibrium paths (excluding the MNF’s initial decision on making an offer first to firm i or firm j, or undertaking greenfield investment) are depicted by arrow heads in Fig. 1. The MNF has to compare its payoffs to find out about the optimal entry mode. Without loss of generality, let firm i be the ex-post efficient firm such that \(\theta _i \le \theta _j\). It is clear from Eq. (3) that the MNF has to pay more to acquire the ex-post efficient firm such that \(\pi ^{e}_{i}(\theta _j)\ge \pi ^{e}_{j}(\theta _i)\). That said, the ex-post efficient firm, however, increases ex-post profits by more than the increase in the acquisition price leading to the unique SPNE of the game depicted in Fig. 1 and to the optimal foreign market entry mode:

Proposition 1

(SPNE in pure strategies) The unique SPNE of the game in pure strategies is that the MNF makes the initial offer to ex-post efficient firm k, \(k\in \,\{i,j\}\)(that reduces the ex-post marginal cost of the investor the most) and this offer is accepted leading the MNF to acquire ex-post efficient firm k. In equilibrium, the MNF will earn\(\pi ^v_m=\pi ^v(\theta _k)-\pi _k^e(\theta _{-k})\ge \pi _m^g\), and the acquired and the non-acquired firms will earn, respectively,\(\pi ^v_k=\pi _k^e(\theta _{-k})\)and\(\pi _{-k}^e(\theta _k)\).

Proof

There is a clear ranking of the payoffs: \([\pi ^v(\theta _i)-\pi _i^e(\theta _j)] \ge [\pi ^v(\theta _j)-\pi _j^e(\theta _i)]\ge \pi _m^g\), \(\forall\)\(\theta _k\in [0,(2c+3c^*-1)/4]\), \(k\in \{i,j\}\), where \(\theta _i \le \theta _j\). \(\square\)

This result extends the finding on domestic acquisitions (by the IO literature modeling the consumer-surplus standard as a competition policy practice) to foreign acquisitions for which a consumer welfare argument is applied as part of a foreign market entry regulation, and suggests that acquisition of existing assets of a local firm that fulfills the minimum output requirement for foreign acquisition given by Condition 1 is also in the best interest of the investor as compared to greenfield entry. The next section shows that this result also extends to the case where foreign acquisition takes place via an auction, so long as both firms qualify for the minimum output requirement.

2.2 Foreign acquisition by an auction

The MNF can make multiple offers simultaneously as an alternative to sequential offers. Multiple offers in this respect can be modeled as auctions. In this section, foreign acquisition of existing assets of a local firm is modeled such that the MNF’s (net) acquisition profit is determined by the local firms’ bids in an open (reverse) ascending auction. That is, the investor (buyer) asks the local firms (sellers) to participate in an ascending auction and to quote prices that they would like to give to the investor as the investor’s share from acquisition profits.Footnote 10 Given that there are only two firms, the specific mechanism is as follows. The price starts from low levels and increases continuously, while bidders keep pressing a button. At any price, any bidder can release the button and can drop out from the auction. Once one firm drops out, the other firm is declared to be the winner.Footnote 11 The MNF acquires the winning firm’s assets, and competes against the other firm in Cournot duopoly. Acquisition profits are shared between the MNF and the acquired firm such that the price at which the firm has dropped out in the auction will be kept by the MNF, and the rest will be paid to the winning firm as a compensation for its assets.

In the auction, firm k’s willingness to pay to the MNF as the MNF’s share from acquisition profits is given by

which represents the local firms’ valuation of foreign acquisition of their assets by the MNF. Their valuation depends on two effects:

-

1.

The increase in profits compared to greenfield profits if the investor acquires firm k’s assets, that is, \(\pi ^v(\theta _k)-\pi _k^g>0\); \(\theta _k\in [0,(2c+3c^*-1)/4]\); \(k\in \{i,j\}.\)

-

2.

The decrease in profits compared to greenfield profits if the investor acquires the other firm’s assets, that is, \(\pi ^e_k(\theta _{-k})-\pi _k^g\le 0\); \(\theta _{-k}\in [0,(2c+3c^*-1)/4]\); \(k\in \{i,j\}.\)

The first effect is equivalent to firms’ takeover valuations as in Norbäck and Persson (2008). The second effect is the negative externality exerted on the non-acquired firm due to the strategic use of a consumer welfare argument in regulating foreign market entry that warrants a minimum output requirement for foreign acquisition as given by Condition 1. Following Norbäck and Persson (2008), it is now clear that

Lemma 2

(Preemptive motive) A minimum output requirement for foreign acquisition leads the local firms to compete for foreign acquisition of their assets by their preemptive valuations, given by equation (4), that are greater than their takeover valuations.

As discussed earlier, the negative externality exerted on the non-acquired firm increases with a decrease in the ex-post marginal cost of the new entity, while the gain from foreign acquisition increases with a decrease in the ex-post marginal cost of the new entity. The proof of Proposition 1 has already shown that (i) the local firms’ preemptive valuations given by Eq. (4) are greater than the MNF’s greenfield profits, which can be considered as the minimum acceptable (reservation) bid, that is, the MNF will not accept any lower price; and that (ii) the ex-post efficient local firm has a higher preemptive valuation than the other firm. For the ex-post efficient firm, it is easy to show that it is individually rational to participate in the auction. As for the firm with a lower valuation, however, a specific belief structure is warranted. The reason is that in this model with complete information, the firm with a lower valuation (the ex-post inefficient firm) is indifferent between participating and seriously bidding in the auction and not participating (or participating, but dropping out at zero price); in either case it can be argued that the ex-post inefficient firm would have to compete against the new entity. If, however, the ex-post inefficient firm believes there is some chance (though arbitrarily small) that the ex-post efficient firm may drop out before the price reaches its valuation, then not only participating (bidding seriously) in the auction is individually rational for both local firms, but also in a pure-strategy equilibrium, the firm with lower valuation will stay active in the auction until the price reaches its valuation.

This leads to

Lemma 3

(Equilibrium price in the auction) In a pure-strategy equilibrium, (i) the (ex-post inefficient) firm with a lower preemptive valuation drops out once the price is equal to its preemptive valuation; (ii) the (ex-post efficient) firm with a higher preemptive valuation wins the auction at a price that is equal to the ex-post inefficient firm’s preemptive valuation; and thus, (iii) the investor can acquire the ex-post efficient firm’s assets and compete against the ex-post inefficient firm in Cournot duopoly, and can earn a share of acquisition profits equal to the ex-post inefficient firm’s preemptive valuation, given by Eq. (4).

Proof

Let \(\epsilon\) be an arbitrarily small probability of the ex-post efficient firm dropping out before the price reaches the ex-post inefficient firm’s valuation. In open ascending auctions, bidders, observing each other’s decision on staying active, evaluate whether or not to stay active at every price that is announced. Given that the firms’ valuations are common knowledge, each firm knows the maximum price, beyond which a firm will not stay active so as to secure non-negative surplus. The ex-post efficient firm (with a higher valuation than the other firm) participates in the auction and stays active so long as the rival firm is active. As for the firm with a lower valuation, given its belief that the ex-post efficient firm drops out at any price below its valuation with (an arbitrarily small) probability \(\epsilon\) (\(\lim _{\epsilon \rightarrow 0}\)), participating in the auction is also individually rational, and it stays active until the price reaches its valuation as there is some chance (though arbitrarily small) that the ex-post efficient firm may drop out leading to a greater profit (see below) than the profit it can earn should it not participate in the auction or should it drop out at any price below its valuation. \(\square\)

Without loss of generality, let firm i be the ex-post efficient firm such that \(\theta _i \le \theta _j\). The investor acquires firm i’s assets and competes against firm j in Cournot duopoly. Firm j earns \(\pi _j^e(\theta _i)\), while the acquisition profits are equal to \(\pi ^v(\theta _i)\), and are shared by the investor and firm i such that

-

the investor will receive a share equal to the equilibrium price in the auction: \(\pi _m^v=\pi ^v(\theta _j)-\pi _j^e(\theta _i)\ge \pi _m^g\) for any \(\theta _k\in [0,(2c+3c^*-1)/4]\), \(k\in \{i,j\}\), where \(\theta _i \le \theta _j\), and

-

firm i will keep the rest: \(\pi _i^v=\pi ^v(\theta _i)-[\pi ^v(\theta _j)-\pi _j^e(\theta _i)]\ge \pi _i^e(\theta _j)\), for any \(\theta _k\in [0,(2c+3c^*-1)/4]\), \(k\in \{i,j\}\), where \(\theta _i \le \theta _j\).

This immediately leads to

Corollary 1

(Optimal entry mode via an auction) Using an auction for foreign acquisition that warrants a minimum output requirement does not change the investor’s optimal entry mode: foreign acquisition is in the best interest of the MNF as compared to greenfield entry.

Comparing the MNF’s and the local firms’ profits in the auction with those from sequential offers (given by Proposition 1) leads to a similar result that can be argued to hold also for domestic acquisitions for which a consumer-surplus standard is employed as part of a competition policy practice:

Proposition 2

(Preferred method of foreign acquisition) The investor prefers the method of sequential offers to an auction, whereas the sum of the local firms’ profits are greater in the auction than in the case of sequential offers.

Proof

The investor’s share from acquisition profits is bigger when the method of foreign acquisition is to make local firms sequential offers than when it is an auction, that is, \([\pi ^v(\theta _i)-\pi _i^e(\theta _j)] \ge [\pi ^v(\theta _j)-\pi _j^e(\theta _i)]\ge \pi _m^g\), \(\forall\)\(\theta _k\in [0,(2c+3c^*-1)/4]\), \(k\in \{i,j\}\), where \(\theta _i \le \theta _j\). The non-acquired firm’s profit is the same in both methods as the MNF acquires the ex-post efficient firm’s assets in either case. The ex-post efficient firm, however, appropriates a share of gains from foreign acquisition in the auction as the price it pays to the MNF (the non-acquired firm’s preemptive valuation) is below its valuation: \(\pi _i^v=\pi ^v(\theta _i)-[\pi ^v(\theta _j)-\pi _j^e(\theta _i)]\ge \pi _i^e(\theta _j)\), for any \(\theta _k\in [0,(2c+3c^*-1)/4]\), \(k\in \{i,j\}\), where \(\theta _i \le \theta _j\). \(\square\)

Proposition 2 implies that although the MNF prefers negotiations over an auction, the host country may ask the MNF to conduct an auction in the case of foreign acquisition as (while consumer welfare is the same in both methods) the sum of the local firms’ profits (and thus aggregate welfare) are greater in the auction than in sequential offers.

To extend the discussions in this section to a general bargaining model, a generalized Nash bargaining solution concept is considered in “Appendix 1”. The results suggest that, depending on the MNF’s and the local firms’ bargaining power, and on their disagreement profits (threat points), (i) the MNF’s profit can be the same as in sequential offers, or less than that in both negotiations and the auction; (ii) the acquired firm’s profit can be the same as, or even more than that in sequential offers; and (iii) conditional on foreign acquisition taking place, the non-acquired firm’s profits will always stay the same as in any mechanism. That said, irrespective of the firms’ bargaining power and disagreement profits, the MNF prefers acquiring the ex-post efficient firm’s assets, which is at least as good as greenfield entry (strictly preferred to greenfield investment for non-zero values of the MNF’s bargaining power) so long as foreign acquisition fulfills Condition 1.

3 Private cost information

This section extends the model to incomplete cost information. Suppose now that the ex-post marginal cost of the new entity is the (to-be-acquired) local firm’s private information. As is commonly used in the literature, the private information that each firm holds is referred to as its type, and thus the ex-post marginal cost of the new entity will be referred to as the local firm’s type: \(\theta _{k}\), \(k\in \{i,j\}\), represents firm k’s type.Footnote 12 Each local firm knows the realization of the new entity’s marginal cost if it is acquired by the MNF, but this is not known by the rival local firm or by the MNF.Footnote 13 However, the distribution of \(\theta\) is common knowledge. To keep the extension of the model as simple as possible, the local firms’ types \(\theta _k\), \(k\in \{i,j\}\), are assumed to be independently and (identically) uniformly distributed over the interval \([0,\overline{\theta }]\) where \(\overline{\theta }\) can take any value in the range \(0<\overline{\theta }\le \left( 2c+3c^{*}-1\right) /4\), and measures the size of the support of the possible cost types.Footnote 14 The upper bound follows Condition 1. The analysis in this section (and in the following section) is carried out for any value of \(\overline{\theta }\) in the relevant range (including the case that this measure is maximized for a minimum output requirement for foreign acquisition given by Condition 1) so as to see the impact of this measure on multinational behavior and on local welfare.

In this section, foreign acquisition is modeled such that the MNF’s (net) acquisition profit is determined by the local firms’ bids in a second-price, sealed-bid auction.Footnote 15 In a second-price sealed-bid auction, each risk-neutral local firm independently submits a single bid without observing the rival’s bid. The MNF acquires the existing assets of the firm making the highest bid, and earns the second-highest bid as its share from acquisition profits.Footnote 16 Similar to the valuations of the firms in the ascending auction under complete information, each local firm’s bid represents its willingness to pay to the MNF as its share from acquisition profits, and thus, the MNF will earn \(\pi _{m}^{v}\) equal to the runner-up’s willingness to pay. The difference is that there is now incomplete cost information: firm k of type \(\theta _k\) has a valuation that is not only a function of its own type, but also a function of the rival firm’s type (due to negative externality implied by the minimum output requirement for foreign acquisition), which is the rival firm’s private information; see Eq. (4) for the local firms’ valuations. “Appendix 2” proves that

Proposition 3

(Equilibrium bids and optimal entry) In a pure-strategy symmetric separating equilibrium, firm\(k\in \{i,j\}\)bids\(b_{k}(\theta _{k})=[\pi ^{v}(\theta _{k})-\pi _{k}^{e}(\theta _{-k})\vert _{\theta _{-k}\rightarrow \theta _k}]>\pi _m^g\), \(\forall\)\(\theta _k\in [0,\overline{\theta }]\), where\(0<\overline{\theta }\le (2c+3c^{*}-1)/4\)and\(b^\prime _{k}(\theta _{k})<0\).

It is clear from Proposition 3 that foreign acquisition that fulfills the minimum output requirement (given by Condition 1) still earns the MNF more than greenfield entry, even when private local targets know more about potential gains from foreign acquisition.Footnote 17 Holding an auction leads the MNF to avoid the lemon’s problem such that it always picks a relatively efficient firm. The reason is that a firm’s optimal bid is negatively related to its own type. The more productive the foreign acquisition, the smaller the size of \(\theta _k\), \(k\in \{i,j\}\), the higher the local firm’s bid. Therefore, the MNF can pick a good-type firm via the auction because the winner will be the firm making the highest bid, that is, the firm making foreign acquisition most productive.

Without loss of generality, let firm i be the ex-post efficient firm such that \(\theta _i \le \theta _j\). Then, the MNF acquires firm i’s assets and competes against firm j in Cournot duopoly. Firm j earns \(\pi _j^e(\theta _i)\), while the acquisition profits are equal to \(\pi ^v(\theta _i)\), and are shared by the MNF and firm i such that

-

the MNF will receive a share equal to the firm j’s bid in the second-price auction: \(\pi _m^v=\pi ^v(\theta _j)-\pi _j^e(\theta _i)\vert _{\theta _{i}\rightarrow \theta _j}\ge \pi _m^g\) for any \(\theta _k\in [0,(2c+3c^*-1)/4]\), \(k\in \{i,j\}\), where \(\pi _j^e(\theta _i)\vert _{\theta _{i}\rightarrow \theta _j}\equiv \pi _i^e(\theta _j)\ge \pi _j^e(\theta _i)\), as can be seen from Eq. (3), and \(\theta _i \le \theta _j\);

-

firm i will keep the rest: \(\pi _i^v=\pi ^v(\theta _i)-[\pi ^v(\theta _j)-\pi _j^e(\theta _i)\vert _{\theta _{i}\rightarrow \theta _j}]\ge \pi _i^e(\theta _j)\), for any \(\theta _i \le \theta _j\), where \(\pi ^v(\theta _j)-\pi _j^e(\theta _i)\vert _{\theta _{i}\rightarrow \theta _j} \le \pi ^v(\theta _j)-\pi _j^e(\theta _i)\) as \(\pi _j^e(\theta _i)\vert _{\theta _{i}\rightarrow \theta _j}\equiv \pi _i^e(\theta _j)\ge \pi _j^e(\theta _i)\).

This immediately leads to

Proposition 4

(Private information) From an ex-post perspective, the local firm that reduces the ex-post marginal cost of the investor the most appropriates a bigger share from acquisition gains when potential gains from foreign acquisition are the local firms’ private information than when such gains are common knowledge.

One interpretation of Proposition 4 (along with the other results) could be that, as far as uncertainties in R&D outcomes are concerned, the strategic use of a consumer welfare argument in regulating foreign market entry, which warrants a minimum output requirement for foreign acquisition, may have important implications on R&D activities of the local firms facing potential market entry by a more efficient foreign firm: engaging in R&D activities (insofar as the outcome is positive) (i) may make the local firms more efficient, and thus more profitable against a greenfield entrant; (ii) may help them qualify for foreign acquisition warranting a minimum output requirement; (iii) may help them alleviate a possible negative externality exerted by a rival’s takeover by the MNF; and (iv) may enable them to generate some private information on potential acquisition gains as this will lead to lower bids for foreign acquisition so as to avoid the winner’s curse (so as to avoid an undesirable outcome of paying unnecessarily more due to information asymmetries).

4 Welfare implications

In this section, welfare ramifications of greenfield investment and foreign acquisition that fulfills the minimum output requirement (given by Condition 1) are scrutinized. That is, this section studies the first stage of game, in which the host country decides whether or not to allow for foreign market entry. Local welfare is defined as the sum of consumer welfare and total profits of the domestic firms (Eq. (9), “Appendix 3”). Let \(W^{a}(c)\) and \(W^{g}(c,c^{*})\) denote local welfare, respectively, when there is no foreign market entry (local duopoly) in the host country and when the MNF invests in new assets (greenfield entry). Also denote by \(W_{a}^{g}\) the welfare change relative to local duopoly when the MNF undertakes greenfield investment. It is straightforward to show that (see “Appendix 3” for details)

Lemma 4

(Greenfield FDI and welfare) Relative to local duopoly, local welfare improves with greenfield entry (\(W_{a}^{g}>0\)) if the MNF is sufficiently productive vis-à-vis the local firms.

Local competition increases with greenfield investment because a more productive firm enters the market and increases the number of firms, which increases production and decreases the market price, and thus increases consumer welfare. The more productive the foreign firm—the smaller is \(c^{*}\)—the more the increase in consumer welfare. Although the local firms’ profits decrease with the investor’s greenfield entry, consumer welfare increases by more than the decrease in local firms’ profits, especially when the industry’s average marginal cost decreases sufficiently with greenfield entry.

From an ex-ante perspective, the host country has to form expectations over local welfare when the MNF enters the market by acquiring a local firm’s assets, denoted \(W^{v}\), as the ex-post marginal cost of the acquired firm is private information. Let \(E_{\theta }\left[ W^{v}\right]\) denote the expected value of \(W^{v}\), which is a function of \(\overline{\theta }\), as \(\theta _k\), \(k\in \{i,j\}\), is distributed over support \([0,\overline{\theta }]\). Computations show that the wider is the interval over which the ex-post marginal costs are distributed (the bigger is the size of \(\overline{\theta }\) within the permissible range implied by the minimum output requirement for foreign acquisition), the higher is local welfare with foreign acquisition (see “Appendix 3” for details). The intuition is as follows. If the size of the support of the possible cost types is bigger, the ex-post marginal cost of the acquired firm is expected to be higher, with which the expected increase in aggregate production will be less, and thus the expected decrease in the market price will be less: consumer welfare is expected to increase less. Similarly, the expected gains from foreign acquisition will be less, although the local firm is expected to increase its share from acquisition profits as the bids decrease by more than the decrease in expected acquisition profits. As for the non-acquired firm, the negative impact of firm acquisition is expected to be less severe. Denoting by \(E[W_{a}^{v}]\) the expected welfare change relative to local duopoly when the MNF enters the market by foreign acquisition, it can be shown that (see “Appendix 3” for details)

Proposition 5

(Foreign acquisition and welfare) Relative to local duopoly, foreign acquisition is expected to improve welfare (\(E[W_{a}^{v}]>0\)) if the local firms have, ex ante, sufficiently high marginal costs, or if the size of the support of the potential cost types is sufficiently large.

With which entry mode does local welfare improve more? Let \(E[W_{g}^{v}]\) denote the expected welfare change relative to greenfield investment when the MNF enters the market by foreign acquisition. It is clear from Lemma 4 and Proposition 5 that foreign market entry (by either way) improves local welfare (relative to local duopoly) when the MNF is sufficiently productive (relative to the local firms), and when the local firms have, ex ante, sufficiently high marginal costs. Also, Proposition 5 suggests that a sufficiently wide interval over which the ex-post marginal cost of the acquired firm is distributed plays an important role in the welfare implications of foreign acquisition. It can be deduced that ex-ante cost asymmetry between the MNF and the local firms, or potential (ex-post) firm heterogeneity (as measured by the size of the support of the potential cost types) seems to be the key for welfare improvement. “Appendix 4” proves that

Proposition 6

(Welfare comparison) Relative to local duopoly, when the degree of potential firm heterogeneity with foreign market entry is sufficiently high, local welfare improves, and does so more with foreign acquisition subject to a minimum output requirement than with greenfield entry.

Both greenfield entry and foreign acquisition increase local competition relative to local duopoly. In the greenfield entry case, a more productive firm enters the market and increases the number of firms, whereas in the case of foreign acquisition, a more productive firm replaces a less productive firm. The average productivity in the industry increases, which increases aggregate production and decreases the market price, and thus consumer welfare increases with foreign market entry. The strategic use of a consumer welfare argument in regulating foreign market entry guarantees a size of consumer welfare with foreign acquisition that is at least as big as one with greenfield investment. Moreover, while greenfield entry decreases both firms’ profits relative to local duopoly, foreign acquisition decreases only the non-acquired firm’s profits.

The following questions are important to understand the policy implications of the model. Under what parameter values of c, \(c^{*}\) and \(\overline{\theta }\), if any, is it optimal for the host country to permit only greenfield entry? In which situations, if any, is it optimal for the host country to ban foreign market entry? Figure 2 uses the parameter constraints implied by the model and illustrates the policy implications, simply by dividing the relevant area into four different regions. In Regions I, II and III, \(c^{*}>\left( 26c-11\right) /15\), and in Region IV, \(c^{*}<\left( 26c-11\right) /15\); relative to local duopoly, greenfield entry improves welfare only in Region IV (Lemma 4 and “Appendix 3”). Moreover, in Regions III and IV, \(c>4/9\); relative to local duopoly, foreign acquisition improves welfare in these two regions, whereas in Region II, where \(c<4/9\), foreign acquisition improves welfare if and only if \(\overline{\theta }>\widetilde{\overline{\theta }}(c)\) (Proposition 5 and “Appendix 3”). In Region I, where \(c<4/9\) and \(\overline{\theta }<\widetilde{\overline{\theta }}(c)\), relative to local duopoly, welfare deteriorates not only with greenfield entry, but also with foreign acquisition.

Clearly, foreign acquisition that fulfills the minimum output requirement based on consumer welfare is preferred not only by the MNF, but also by the host country, especially in Regions III, and IV, as well as in Regions II insofar as the size of the support of the potential cost types is sufficiently large. In Regions II and III, however, the host country may consider introducing restrictive measures on greenfield entry as it deteriorates welfare. In Region I, the host country may want to introduce restrictive measures on foreign market entry. This is also the case in Region II if the size of the support of the potential cost types is not sufficiently large. It is now clear that

Corollary 2

(Policy implication) The strategic use of a consumer welfare argument in regulating foreign market entry, which warrants a minimum output requirement for foreign acquisition, aligns the nationally optimal entry mode to the MNF’s optimal entry mode, unless the local firms are fairly productive.

It is not optimal for the host country to permit greenfield entry and prohibit foreign acquisition. On the contrary, for any permissible greenfield entry (Region IV in Fig. 2), the model predicts that foreign acquisition that fulfills the minimum output requirement given by Condition 1 is optimal not only for the MNF, but also for the host country. This prediction is consistent with what UNCTAD (2000) has reported, that is, allowing for foreign ownership is mostly accompanied by permitting also foreign acquisitions of local assets subject to some enforcement practices.Footnote 18

5 Extensions and discussions

This section provides an alternative interpretation of the model that captures the trade aspect of the model, and discusses potential implications of buyer competition for foreign acquisition when the host country strategically uses a consumer welfare argument in regulating foreign market entry.

5.1 Trade liberalization

Although the analyses in the previous sections have been conducted by focusing on the choice of the MNF between foreign acquisition and greenfield entry and by modeling negotiations for foreign market entry between the host country and the MNF, the same analyses apply in the case of complete trade liberalization that abolishes all trade costs.Footnote 19 In such a case, the MNF will be indifferent between trade and greenfield investment (without any fixed investment costs) as both will earn the MNF the same profit as in Eq. (2). As is now clear, the rest of the analyses will be the same as in previous sections leading to an important result:

Proposition 7

Foreign acquisition fulfilling the minimum output requirement imposed by the host country as part of the foreign market entry regulation is in the best interest of the multinational even when there is complete trade liberalization.

Statistical evidence shows that cross-border mergers and acquisitions have surpassed greenfield investment, which has dominated international trade since the 1980s, around the time most countries liberalized trade and foreign investments. Traditional trade and FDI models, (i.e., the proximity-concentration trade off and the tariff-jumping hypothesis) however, suggest that multinationals face a trade-off between trade costs and fixed investment costs when choosing between trade and greenfield investment, and thus complete trade liberalization that abolishes trade costs should lead firms to trade, but not to FDI. Koska et al. (2018) show that if there is ex ante incomplete cost information, and if FDI can serve as a signal of high productivity, then FDI can be optimal even when trade costs are zero. Alternatively, Koska (2015) shows that complete trade liberalization can be aligned with the surge in greenfield investment and cross-border mergers and acquisitions so long as (i) investment and trade liberalizations are carried out together, and (ii) there is multinational competition for FDI. This study now shows that without competition, a multinational firm may still prefer FDI through acquisition of a local firm under complete trade liberalization insofar as the host country strategically uses a consumer-surplus standard to regulate foreign market entry.

5.2 Buyer competition for foreign acquisition

Similar to the analysis by Norbäck and Persson (2008) discussing the profitability of foreign acquisitions under both seller and buyer competition, the model can be reversed such that there is a single local firm and two multinationals that compete for foreign market penetration. In this case, a minimum output requirement for foreign acquisition can be modeled as follows. After having invested in a specific factor that makes the two multinationals productive for the market, the multinationals express their interest in entering the market. The host country then asks the multinationals to open their books,which will reveal the particulars of their performance should they enter the host country via independent sales (greenfield investment or trade under complete liberalization), and solves their problem backwards, so as to require any multinational that would like to acquire the local firm to commit to not produce below a certain output level in the case of entry by foreign acquisition (which puts an upper bound on ex-post marginal production costs in the Cournot setting with constant marginal costs).

Choosing the minimum output requirement for foreign acquisition as one that leads to the same aggregate output as in the case both multinationals enter the market via independent foreign sales, the host country can lead the multinationals to compete for the local firm for preemptive reasons: given the rival firm opts for independent foreign sales, each firm can gain more by deviating and acquiring the local firm relative to the case both firms opt for independent foreign sales; and if the rival multinational acquires the local firm, the non-acquiring multinational’s profit decreases relative to its profit when both multinationals opt for independent foreign sales. Therefore, both multinationals’ preemptive valuations are greater than their takeover valuations for foreign acquisition, and each multinational will have a strong incentive to preempt the rival’s acquisition of the local firm, which can be referred to as “buyer competition” for foreign acquisition.

In such a case, if the multinationals’ ex-post marginal costs (in the case of foreign acquisition) are sufficiently close to each other, then their preemptive valuations are sufficiently close to each other, which leads to fierce competition (a bidding war) for foreign acquisition. In this case, fierce competition among multinationals for the acquisition of the local firm even may bid up the price to the extent that the multinationals would have been better off had they both undertaken greenfield investment. In such a case, it may turn out that the strategic use of a consumer welfare argument in regulating foreign market entry may lead to a prisoner’s dilemma situation for the multinationals, although the results would still suggest a preemptive foreign takeover by the ex-post more efficient multinational in a non-cooperative equilibrium, and even greater local welfare for the host country (see Koska 2018, for details).

6 Concluding remarks

Foreign acquisitions can be anti-competitive and foreign market entry by multinationals can have detrimental effects on local welfare. To avoid such anti-competitive outcomes of foreign acquisitions and detrimental welfare effects of multinational behavior, most countries regulate foreign market entry and negotiate with multinationals, not only to encourage them for foreign direct investment, but also for certain production requirements. In a simple Cournot oligopoly model, this study has incorporated the strategic use of a consumer welfare argument into foreign market entry regulations and has scrutinized potential market entry by a multinational (either by greenfield investment/trade, or via foreign acquisition of a local firm) and its welfare implications. The results have shown that any foreign acquisition fulfilling a minimum output requirement imposed by the host country as part of the foreign market entry regulation is in the best interest of the multinational even when there is complete trade liberalization. A local firm appropriates a bigger share from acquisition gains in an auction, and prefers generating information asymmetries. Welfare improves with a larger scope for ex-post firm heterogeneity when the foreign market entry regulation includes a minimum output requirement for foreign acquisition based on consumer welfare. According to the results, it can be argued that the strategic use of a consumer welfare argument in regulating foreign market entry may be most beneficial especially in under-performing oligopolistic industries (with entry barriers) in which local firms are fairly unproductive, and may even have important implications on local R&D activities.

Notes

In the late 1990s and the early 2000s, the share of cross-border mergers and acquisitions in global FDI was around 75 and 60%, respectively (Navaretti and Venables 2004). This type of foreign market entry is, however, too sensitive to global economic changes, and thus was negatively and significantly affected by the economic crises, the last of which hit the global economy in 2008. After some recovery period, according to UNCTAD (2014, 2015), around 25-30% of all global FDI took place as such investment lately (valued at US$349bn in 2013, and US$400bn in 2014).

The existing literature, by and large, agrees that (i) firms benefit from combining assets, especially under sufficient efficiency gains, sufficiently convex demand or differentiated products, or when products/assets are strategic complements; and (ii) firms prefer greenfield entry to acquiring a firm’s existing assets if there are significant asymmetries in asset structures and little scope for synergies, or if the costs of shared ownership (e.g., dissipation of proprietary knowledge) are relatively high.

The MNF has a cost advantage over the local firms: \(c^{*}<c\), as this is the common observation in most countries where multinationals are actively operating; see Navaretti and Venables (2004).

As the focus of this study is the implications of the strategic use of a consumer-surplus standard in regulating foreign market entry on multinational behavior and local welfare, the study focuses only on the cases that fulfills the minimum output requirement given by Condition 1, and assumes that both local target firms qualify for foreign acquisition in that sense.

While the MNF will not exclude any target firm from negotiations so as to decrease the acquisition price, especially given the minimum output requirement for foreign acquisition that generates a credible threat on the local firms (see Lemma 1 in Sect. 2.1), a more general bargaining model for acquisition of existing assets of a local firm, generalized Nash bargaining, is given in “Appendix 1”.

It should be clear in the following sections that even under non-prohibitive fixed investment costs all results stay intact.

This assumption is the implication of the fact that the host country will not allow the MNF to earn monopoly profits by greenfield entry.

There are many formats by which this auction could be run. As the investor’s revenues coincide for all formats, an ascending auction format is considered here. In the case of incomplete cost information, for the ease of exposition, a second-price sealed-bid auction is considered.

If both firms drop out at the same price, then the investor randomly picks one firm.

Firm i is a good-type firm relative to firm j if \(\theta _{i}<\theta _{j}\), or a bad-type firm if \(\theta _{i}>\theta _{j}\).

The new entity’s marginal cost is the local firms’ private information at the time of the auction, but will be revealed after the auction. This is merely a simplification as the MNF can easily find out each firm’s type, simply by observing how much each firm offers in the auction, then by solving the problem backwards. In particular, with the revelation assumption, the optimal entry mode can be figured out without assigning any probabilities to the realization of firms’ true types. If the firms’ types were to remain private information even after the auction, there would have been Bayesian equilibria without further insights such that the firms would have determined their equilibrium production levels according to their beliefs about their opponent’s type, and hence the equilibrium profit levels given by Eq. (3) would have changed to include such beliefs.

An alternative interpretation could be that it measures ex-post firm heterogeneity. For a similar interpretation, see Koska et al. (2018).

In terms of the firms’ bidding strategies with independent private values, a second-price auction is equivalent to an ascending auction, while a first-price auction is equivalent to a descending auction. That said, the Revenue Equivalence Theorem suggests that if the bidders are risk-neutral and if they have privately known values independently and identically drawn from a common and strictly increasing distribution, any symmetric equilibrium of any standard auction, in which the expected payment of the bidder with the lowest value is zero and the bidder with the highest value wins, yields the same expected revenue for the seller; see Krishna (2002).

If the firms bid the same price, then the MNF randomly chooses the firm to acquire. The acquisition profits are determined after the auction is over, and after the MNF and the non-acquired firm competes against each other in Cournot duopoly. Once the Cournot profits are realized, the MNF and the acquired firm share the acquisition profits according to the outcome of the auction.

Raff et al. (2009b), considering a model in which a local firm’s private information is its potentially valuable assets, and Qiu and Zhou (2006), considering a model in which local firms know more about local demand, find a similar result. Raff et al. (2009b) also show that this prediction is consistent with the ownership choices of Japanese multinationals.

As in the case of greenfield entry with or without non-prohibitive fixed investment costs, the model can also accommodate some non-prohibitive per-unit trade/transport costs, and the results will be qualitatively similar, although unlike the case with or without non-prohibitive fixed investment costs, some modifications of the equations will be warranted with non-prohibitive per-unit trade costs.

References

Ang, J., & Kohers, N. (2001). The take-over market for privately held companies: The US experience. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 25, 723–748.

Bjorvatn, K. (2004). Economic integration and the profitability of cross-border mergers and acquisitions. European Economic Review, 48, 1211–1226.

Breinlich, H., Nocke, V., & Schutz, N. (2017). International aspects of merger policy: A survey. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 50, 415–429.

Breinlich, H., Nocke, V., & Schutz, N. (2015). Merger policy in a quantitative model of international trade (CEPR Discussion Paper 10851). Center for Economic Policy Research.

Castellani, D., & Zanfei, A. (2007). Internationalisation, innovation and productivity: How do firms differ in Italy? World Economy, 30, 156–176.

Deneckere, R., & Davidson, C. (1985). Incentive to form coalitions with Bertrand competition. Rand Journal of Economics, 16, 473–486.

Dertwinkel-Kalt, M., & Wey, C. (2016). Merger remedies in oligopoly under a consumer welfare standard. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 32, 150–179.

Desai, M. A., Foley, C. F., & Hines, J. R, Jr. (2004). The costs of shared ownership: Evidence from international joint ventures. Journal of Financial Economics, 73, 323–374.

Ding, W., Fan, C., & Wolfstetter, E. G. (2013). Horizontal mergers with synergies: Cash vs. profit-share auctions. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 31, 382–391.

Draper, P., & Paudyal, K. (2006). Acquisitions: Private versus public. European Financial Management, 12, 57–80.

Farrell, J., & Shapiro, C. (1990). Horizontal mergers: An equilibrium analysis. American Economic Review, 80, 107–126.

Fatica, S. (2010). Investment liberalization and cross-border acquisitions: The effect of partial foreign ownership. Review of International Economics, 18, 320–333.

García-Canal, E., Lópes Duarte, C., Rialp, J., & Valdés, A. (2002). Accelerating international expansion through global alliances: A typology of cooperative strategies. Journal of World Business, 37, 91–107.

Goeree, J. K. (2003). Bidding for the future: Signaling in auctions with an aftermarket. Journal of Economic Theory, 108, 345–364.

Goppelsroeder, M., Schinkel, M. P., & Tuinstra, J. (2008). Quantifying the scope for efficiency defense in merger control: The Werden–Froeb index. Journal of Industrial Economics, 56, 778–808.

Görg, H. (2000). Analyzing foreign market entry: The choice between greenfield investment and acquisitions. Journal of Economic Studies, 27, 165–181.

Helpman, E., Melitz, M. J., & Yeaple, S. R. (2004). Export versus FDI with heterogeneous firms. American Economic Review, 94, 300–316.

Hennessy, D. A. (2000). Cournot oligopoly conditions under which any horizontal merger is profitable. Review of Industrial Organization, 17, 277–284.

Janssen, M. C. W., & Karamychev, V. A. (2010). Do auctions select efficient firms? Economic Journal, 120, 1319–1344.

Jehiel, P., & Moldovanu, B. (2000). Auctions with downstream interaction among buyers. Rand Journal of Economics, 31, 768–791.

Koska, O. A. (2015). A model of competition between multinationals. METU Studies in Development, 42, 271–298.

Koska, O.A. (2018). Gains from multinational competition for cross-border firm acquisition (Economics Discussion Papers, No 2018-19). Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW).

Koska, O. A., Long, N. V., & Stähler, F. (2018). Foreign direct investment as a signal. Review of International Economics, 26, 60–83.

Koska, O. A., Onur, I., & Stähler, F. (2017). The scope of auctions in the presence of downstream interactions and information externalities. Journal of Economics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00712-017-0590-0.

Koska, O. A., & Stähler, F. (2014). Optimal acquisition strategies in unknown territories. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics, 170, 406–426.

Krishna, V. (2002). Auction theory. San Diego: Academic Press.

Lommerud, K. E., & Sorgard, L. (1997). Merger and product range rivalry. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 16, 21–42.

Lópes Duarte, C., & García-Canal, E. (2004). The choice between joint ventures and acquisitions in foreign direct investment: The role of partial acquisitions and accrued experience. Thunderbird International Business Review, 46, 39–58.

Markusen, J., & Stähler, F. (2011). Endogenous market structure and foreign market entry. Review of World Economics, 147, 195–215.

Müller, T. (2007). Analyzing modes of foreign entry: Greenfield investment versus acquisition. Review of International Economics, 15, 93–111.

Navaretti, B. G., & Venables, A. J. (2004). Multinational firms in the world economy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Nocke, V., & Whinston, M. D. (2010). Dynamic merger review. Journal of Political Economy, 118, 1200–1251.

Norbäck, P.-J., & Persson, L. (2008). Globalization and profitability of cross-border mergers and acquisitions. Economic Theory, 35, 241.

Norbäck, P. J., & Persson, L. (2007). Investment liberalization—Why a restrictive cross-border merger policy can be counterproductive. Journal of International Economics, 72, 366–380.

Norbäck, P. J., & Persson, L. (2004). Privatization and foreign competition. Journal of International Economics, 62, 409–416.

Norbäck, P. J., & Persson, L. (2005). Privatization policy in an international oligopoly. Economica, 72, 635–653.

Pagnozzi, M., & Rosato, A. (2016). Entry by takeover: Auctions vs. bilateral negotiations. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 44, 68–84.

Perry, M. K., & Porter, R. H. (1985). Oligopoly and the incentive for horizontal merger. American Economic Review, 75, 219–227.

Qiu, L. D. (2010). Cross-border mergers and strategic alliances. European Economic Review, 54, 818–831.

Qiu, L. D., & Wang, S. (2011). FDI policy, greenfield investment and cross-border mergers. Review of International Economics, 19, 836–851.

Qiu, L. D., & Zhou, W. (2006). International mergers: Incentives and welfare. Journal of International Economics, 68, 38–58.

Raff, H., Ryan, M., & Stähler, F. (2006). Asset ownership and foreign-market entry (CESifo Working Paper. No. 1676). Munich: Center for Economic Studies and Ifo Institute for Economic Research.

Raff, H., Ryan, M., & Stähler, F. (2012). Firm productivity and the foreign-market entry decision. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 21, 849–871.

Raff, H., Ryan, M., & Stähler, F. (2009a). The choice of market entry mode: Greenfield investment, M&A and joint venture. International Review of Economics and Finance, 18, 3–10.

Raff, H., Ryan, M., & Stähler, F. (2009b). Whole vs. shared ownership of foreign affiliates. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 27, 572–581.

Salant, S., Switzer, S., & Reynolds, R. J. (1983). Losses from horizontal merger: The effects of an exogenous change in industry structure on Cournot–Nash equilibrium. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 98, 185–199.

Shen, J., & Reuer, J. R. (2005). Adverse selection in acquisitions of small manufacturing firms: A comparison of private and public targets. Small Business Economics, 24, 393–407.

UNCTAD. (2000). World Investment Report 2000. New York: United Nations.

UNCTAD. (2014). World Investment Report 2014. New York: United Nations.

UNCTAD. (2015). World Investment Report 2015. New York: United Nations.

Acknowledgements