Abstract

Introduction

The choice of the most appropriate approach to valuing productivity loss has received much debate in the literature. The friction cost approach has been proposed as a more appropriate alternative to the human capital approach when valuing productivity loss, although its application remains limited. This study reviews application of the friction cost approach in health economic studies and examines how its use varies in practice across different country settings.

Methods

A systematic review was performed to identify economic evaluation studies that have estimated productivity costs using the friction cost approach and published in English from 1996 to 2013. A standard template was developed and used to extract information from studies meeting the inclusion criteria.

Results

The search yielded 46 studies from 12 countries. Of these, 28 were from the Netherlands. Thirty-five studies reported the length of friction period used, with only 16 stating explicitly the source of the friction period. Nine studies reported the elasticity correction factor used. The reported friction cost approach methods used to derive productivity costs varied in quality across studies from different countries.

Conclusions

Few health economic studies have estimated productivity costs using the friction cost approach. The estimation and reporting of productivity costs using this method appears to differ in quality by country. The review reveals gaps and lack of clarity in reporting of methods for friction cost evaluation. Generating reporting guidelines and country-specific parameters for the friction cost approach is recommended if increased application and accuracy of the method is to be realized.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Economic evaluation is increasingly used to guide the allocation of scarce health care resources [1]. In many cases, economic evaluation studies are restricted to a narrow healthcare perspective [2], although there are strong arguments for consideration of a societal perspective [3]. Arguments in favour of adopting a societal perspective are related to the basic principles of economic evaluations founded in welfare economics [2, 4]. In addition, adopting a narrower perspective would be to deny the reality of costs falling outside the healthcare budget, which could lead to biased health policies for society [5]. If a societal cost perspective is adopted, one of the main areas of controversy is whether and how to include productivity costs. Productivity costs are defined as ‘costs associated with production loss and replacement costs due to illness, disability and death of productive persons, both paid and unpaid’ [6, 8, p 254]. Generally, in relation to paid work, productivity costs relate to benefits forgone to society as a result of absence from work (absenteeism), or working with reduced capacity due to illness (presenteeism), resulting in productivity loss. The main argument raised against incorporating productivity costs in economic evaluation is that they might favour interventions directed at employed individuals over those who are unemployed, as a result of including costs of paid labour and excluding those of unpaid labour [7–9].

There is also debate around methods for estimating productivity costs [3, 6, 10–12]. Indeed, there is no consensus on productivity loss valuation methods in existing national guidelines [13–19]. The two most commonly used approaches are the human capital approach (HCA) and the friction cost approach (FCA). These methods have been found to generate disparate productivity cost estimates [20]. Compared to the human capital approach, the friction cost approach often generates lower estimates, particularly in the long term [9, 21]. The friction cost approach was developed by health economists from the Netherlands who argued that the human capital approach to valuing productivity costs of morbidity and mortality generates overestimated costs from a societal perspective [12, 22]. The method limits productivity loss to the friction period, with friction costs broadly comprising lost production during the friction period and the costs of hiring and training new individuals [23]. Therefore, to effectively estimate productivity costs during the friction period, information is needed on: (1) when a friction period occurs, (2) the length of a friction period, (3) an estimate of production loss, with a particular focus on the elasticity of production versus labour productivity, (4) the costs of searching and training replacement workers and (5) medium-term macro-economic effects. The length of the friction period is the time required to replace a sick individual at their work place, often based on the average vacancy duration [12]. Start and end dates of each absence spell are therefore required in order to effectively apply the friction cost approach. Productivity losses for absence periods shorter than the friction period are then estimated with an elasticity adjustment factor [23]. Studies have demonstrated that work absence affects labour time at work, which in turn affects the productivity of that labour [12, 23]. Therefore, when using the friction cost approach, the change in work time versus work productivity—known as the elasticity factor—is often used to adjust for short-term work compensations. Although the friction cost method is limited to productivity costs in the short term, work absence, reduced productivity and disability could potentially lead to medium-term macroeconomic consequences [12]. A macro-econometric model has previously been recommended as a way of estimating macro-economic consequences of work absence and disability [12]. Some have argued that the friction cost approach is a more appropriate valuation approach, as it explicitly considers economic circumstances that limit production losses due to sickness [11, 12].

While the advantages and limitations of the friction cost approach have been clearly highlighted [10, 12, 23, 24], the number of health economic studies that have attempted to use this method, and their country settings, remains largely unknown [25]. This is important, as the friction cost approach generates more realistic productivity costs than the human capital approach, particularly in the long run, and there are likely to be important variations in key parameters and methods across different countries. No previous literature has comprehensively reviewed whether and how the friction cost approach has been applied within different country settings. A previous review investigated methods used to assess productivity costs in practice in economic evaluation studies, and recommended explicit reporting of methods when using the friction cost approach [26]. However, this review is relatively old and does not illustrate the current state of literature on this method. The more up-to-date review herein aims to inform further research in this area by specifically assessing the use of the friction cost approach in existing studies, to provide a comprehensive assessment of the current state of the literature. To inform this issue, the aim of this review is to investigate two related research questions: (1) To what extent has the friction cost approach been used to estimate productivity costs in economic evaluation? and (2) How consistent are the methods for valuing productivity costs using the friction cost approach?

Methods

A review of published applied economic costing studies was conducted to explore the two research questions stated in the introduction section, with criteria to include studies only if they: (1) were original applied economic evaluation studies; (2) incorporated costs related to productivity costs using the friction cost approach, and described the methods for doing so; and (3) were written in English.

Search strategy

Searches were conducted in MEDLINE (OVID), EMBASE (OVID), PsycINFO (OVID), Web of Science (ISI) and the specific health economics database NHS Economic Evaluation (NHS EED), and were limited to studies published between 1 January 1996 and 31 July 2013. The search strategies used were based on the following predefined search keywords: ‘friction cost’ or ‘friction cost approach’ or ‘friction cost method’ or ‘friction period’. Where relevant, Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) containing the words ‘friction costs’, ‘friction cost approach’, and ‘friction approaches’ were exploded. The list of study titles was supplemented by a bibliographic review of all retrieved papers.

Study selection

Following the removal of duplicates, the selection of studies was carried out in two phases. In the first phase, relevant studies were initially identified by their titles and abstracts. Where there was uncertainty, the full text was retrieved. Full texts for all selected articles were then obtained for the second phase of the review, and studies were excluded at this stage if they did not estimate productivity costs using the friction cost approach, or provided no details as to how the method was used in estimating these costs. Study selection and data extraction were done by one person. Where there was ambiguity, study selection was carried out by all four authors, using the extraction criteria described above.

Data extraction and analysis

A data extraction form was developed to extract systematic information on study country, publication year, type of economic evaluation, disease condition, and data context. To identify methodological characteristics of interest, data were extracted on the friction period value used, the labour elasticity value, the cost of labour/wage rate, whether compensation mechanisms or multiplier effects were included (and if so how?), whether recruitment and training costs were incorporated (and if so how?), and whether macroeconomic effect adjustments were applied. Narrative synthesis was used to summarise and explain the findings.

Results

Study selection

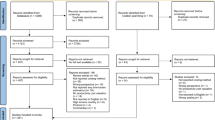

The literature search yielded a total of 186 papers, of which 63 were duplicates, resulting in a total of 123 papers. Of these, ten were systematic reviews not relevant to the friction cost approach, two were editorials or letters, 36 were not relevant to the friction cost approach, and 20 were conference abstracts. All of these were excluded. The full texts of the remaining 55 potentially relevant articles were obtained for the second phase of the study selection. A further 18 articles not meeting the study criteria were subsequently excluded. A further nine articles were located by searching references of the studies obtained from the databases. This resulted in a total of 46 studies that met the criteria for the review. A summary of this process is provided in Fig. 1.

Study characteristics

The characteristics of the 46 studies that are included in this review are presented in Table 1. The majority (n = 28) of the studies were conducted in the Netherlands, and others were conducted elsewhere in Europe, Australia and in North America. Seven studies were set in the United Kingdom [27–33], two in Germany [34, 35], and one in each of the following: Ireland [37], Sweden [38], Canada [21], Spain [39], Denmark [40], Austria [36], Norway [41] and Greece [42] (Table 1). One study, however, was based on a multinational clinical trial setting and used country-specific costing [43]. In addition, one study conducted economic evaluations in both Austria and the Netherlands [36].

The studies evaluated a wide range of disease areas, with the largest group of studies targeting back pain problems [40, 44–50], and mental-health-related disorders including depression [51–55]. Of the remaining studies, four related to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, four to limb disorders, and three to neck pain. All studies are summarised in Table 2. The results show that slightly over 55 % of the studies (n = 27) were published between 2002 and 2007, a period that followed various debates on the most appropriate method of estimating productivity costs. Of the remaining studies, only eight were published prior to 2002, and 11 were published between 2008 and 2013. All studies adopted a “societal” perspective either exclusively or in addition to a narrower perspective. Of studies that also adopted a narrower perspective, nine adopted a healthcare perspective and one used an employer perspective [56]. Two-thirds of the studies used information obtained through randomised clinical trials (RCT), nine were national-prevalence-based studies, one was an observational study, one a national survey and two were economic costing studies based in a hospital setting. The majority of studies were cost-effectiveness analyses (n = 26), of which five incorporated a cost-utility analysis. Of the remaining studies, 13 were economic cost-of-illness studies, and one used both cost-effectiveness analysis and cost benefit analysis.

Methods of estimating productivity costs using the friction cost approach

Overall, the level of detail on the methods used to incorporate productivity costs when using the friction cost approach appears to be driven by type and country of study. The first step in estimating productivity costs using the friction cost approach is to estimate the friction period [12]. Overall, the majority (35, 76 %) of studies explicitly reported the length of the friction period used, although only 16 clearly stated the source of this estimate. Studies that provided a clear source for the friction period were more likely to originate from the Netherlands or provide a friction period estimate obtained from the Netherlands. The explicitly reported sources of friction period data from these studies included the Central Statistics Office (n = 11) and the Dutch Costing Manual (n = 3) from the Netherlands, the Central Statistics Office from Ireland (n = 1), and the Federal Labour Office from Germany (n = 1). The mean length of a friction period was 4 months, and the reported values varied widely between 2 and 6 months. The most frequently used friction period in the studies identified was 3 months. One study used friction period estimates disaggregated by education status from a previous methodological piece of work in the Netherlands (i.e., not assuming a homogeneous market) [12, 45]. Where explicitly reported, the friction period used was from the Netherlands, with the exception of two UK studies that used a friction period estimate reported earlier by Maniadakis and Gray (2000) [30, 31], one from Germany [35], and one from Ireland [56]. In relation to friction costs of hiring and training replacement workers, only one study from Denmark provided estimates of the employers’ friction costs, reporting employer replacement costs of USD 1,670 [40].

The second step in estimating productivity costs using the friction cost approach is to provide a realistic valuation of the lost production during the friction period, often done by applying an elasticity adjustment factor to the cost valuation. Only a few studies (20 %) provided clear details about the elasticity correction factor [29, 35, 37, 41, 45, 57–60]. Of these, seven used an elasticity value of 0.8 originating from the Netherlands [12], and one [41] used a value of 0.7 without providing a clear source. A study from Germany used more than one elasticity value (1, 0.8, and 0.3) for different sick-leave periods, but provided no clear source for these [35]. The reported elasticity values were all based on data from the Netherlands and were obtained from either the central planning bureau or the Dutch economic institute, as reported in the Dutch Costing Manual [61]. In relation to adjustments to productivity costs during the friction period using the elasticity adjustment factor, the majority of studies did not provide enough details to identify whether this adjustment was performed, and neither was the actual estimation approach that was used clearly documented. This lack of detail makes it difficult to compare the calculations used by the studies from different countries. Only one recently published study [35] was identified as having explicitly applied elasticity values for varying sick-leave periods. The studies identified focused on generating short-term friction costs, and the majority did not explicitly estimate a medium-term effect or report using a technique, such as the model applied by Koopmanschap and colleagues [12]. However, three cost-of-illness studies adjusted productivity loss for rate of economic activity and current unemployment alongside the friction period [30, 31, 33].

Studies were also assessed for whether they considered the impact of work absence and reduced productivity at work on teamwork and productivity, often known as multiplier effects [62]. These have been reported to have a significant impact on overall productivity costs [63]. There was no obvious attempt in any study to assess the negative impacts of multiplier effects on overall productivity costs and outcomes. Furthermore, none of the studies considered specific work productivity loss compensation mechanisms shown to significantly reduce the impact of productivity costs on total societal costs [64].

When estimating the time related to productivity costs, the majority (82 %) used self-assessed days or hours absent from work as the productivity loss component for which cost was assessed; four others used certified days of incapacity [31–33, 49]. The rest of the studies did not provide details of the productivity metric used to estimate productivity costs. Only two studies [43, 53] explicitly reported using start and end dates for each absence spell. Most of the studies (46 %) that stated how productivity loss was estimated used a questionnaire. Only a few economic evaluation studies used cost diaries [36, 44, 46, 51, 59, 60, 65]. The studies using national certified work incapacity data (four studies) were cost-of-illness studies. The remaining studies did not provide sufficient information to identify how productivity loss was estimated.

Productivity loss was assessed through valuation of lost time. In the case of absence from work, productivity loss was assessed as the value of forgone time at work. When time was valued by using a wage rate for the value of work time forgone, studies used either a wage rate for the relevant age-sex dependent group (n = 19) or an average wage rate for all groups (n = 18). The exceptions were a weighted-average gross wage rate [43], a median wage rate [29], and the actual wage rate of respondents [36]. Seven studies reported using the age-group gender-based productivity cost per hour from the Dutch Costing Manual [52, 54, 60, 66–68]. The method of valuation of work time forgone could not be ascertained in the remaining four studies.

Indirect costs broadly include a variety of costs such as productivity losses (absenteeism and presenteeism), and informal costs such as family or relatives. All 46 studies that were reviewed included the estimation of lost time due to absence from paid working time, with only one study [54] incorporating loss from reduced productivity whilst at work (presenteeism) using the friction cost method. In this latter study, the researchers generated an estimate of lost productivity through presenteeism by estimating the days worked when ill, multiplied by a self-reported inefficiency score, and used average friction costs per working hour from the Netherlands [61] to value these losses. Only eight of the cost-of-illness studies incorporated costs of premature death by truncating the data to the appropriate friction period [30, 32, 33, 38, 39, 42, 56, 58]. Fifteen studies estimated monetary benefits for unpaid labour and four included patient travel-related costs. Detailed methodological and practical discussions on generating informal costs are demonstrated elsewhere in more detail [69, 70].

Discussion

This review found 46 studies that have applied the friction cost approach in estimating productivity costs. The majority were from the Netherlands, where the friction cost approach was first developed and is recommended in the reference case for economic evaluation [71]. The findings showed wide variations in the application of the friction cost approach and in the quality of reported methods when estimating productivity costs across different countries.

In practice, the length of the friction period has mostly been assessed as an average value assuming a homogeneous labour market across countries. In reality, however, the friction period depends on the level of unemployment (availability of labour) and the ability of the labour market to match demand and supply of labour, suggesting a need to consider different segments of the labour market. The review found only one study [45] that applied disaggregated friction periods by education status from a previous methodological study in the Netherlands (i.e., not assuming a homogeneous market) [12, 45]. The use of an average friction period may result in underestimating productivity costs [23]. Estimates of the elasticity factor and aspects of compensation mechanisms, multiplier effects and medium-term macro-economic effects were not considered in many of the studies that were reviewed. Clearly, there is no consensus on the type of productivity costs included among studies in the different countries. Overall, costing studies incorporating the friction costing approach are few outside the Netherlands, which could perhaps be attributed to the lack of any country context-relevant parameters for the method in these countries.

The findings from this review are in agreement with previous literature assessing the estimation of productivity costs [26]. In their review assessing how productivity costs are valued in economic evaluation practice, Pritchard and Sculpher [26] identified 40 economic evaluation studies, of which only seven used the friction cost approach. The findings from their review indicated that in a number of studies, the methods used to estimate productivity costs were not clearly stated, and they advocated improvements to the reporting of productivity costing methods. This was particularly the case for studies applying the friction cost approach and the US Panel cost-effectiveness approach. Nevertheless, the systematic review in this study differs from their review in two major ways. Firstly, Pritchard and Sculpher [26] assessed applications of the three productivity cost valuation methods. The systematic review here focuses in much greater detail on applications of the friction cost approach, and hence complements the findings from their review, which is now also somewhat dated. Secondly, they review only economic evaluation studies from the Health Economic Evaluation Database. This review considers cost-of-illness and economic evaluation studies from a much wider search, and therefore provides a more comprehensive assessment of the current state of the literature on the application of the friction cost methodology.

The review has some strengths and limitations. It assesses cost-of-illness and original economic evaluation studies from various databases showing how the friction cost approach is used in current practice. Although care has been taken to include all relevant studies in the literature, some studies may have been missed through the use of a search strategy with specific terms such as “friction period” and “friction cost approach”. Moreover, modelling studies were excluded, as the main focus was to assess how friction cost approach data are collected and generated in practice. Additionally, studies could have been missed by excluding non-English articles and through initially reviewing abstracts and titles.

Of the 46 studies reviewed, 28 were from the Netherlands, where practitioners are the strongest advocates of this method. There are more readily available data in the Netherlands, including information about the length of friction period, and the standard friction cost approach-related productivity costs per hour. Currently, a smaller proportion of economic evaluation studies outside the Netherlands formally estimate productivity costs using the friction cost approach. This may relate in part to different system requirements, both in terms of systems that advocate for a focus on health system costs, and those that advocate for a use of a human capital approach to value lost productivity [1]. Another possible reason for limited use, however, resulting from this review may be a lack of empirical data for use in applying the friction cost approach in different settings. For example, the findings showed that when the source of data for the length of a friction period was reported, more often than not, the value originated from the Netherlands, with the exception of few studies [30, 31, 35, 37]. Moreover, the extent to which the readily applied parameters from the Netherlands are appropriate when applied in other settings remains unexplored.

The review shows wide variations in clarity and level of detail in the information provided in the methods used to estimate productivity costs across country settings. In addition, few attempts have been made to disaggregate friction periods according to different population groups [12, 45]; this suggests that the reported friction costs could be underestimated. Koopmanschap et al. [12] previously reported friction period estimates disaggregated by education level in the Netherlands. The findings here confirm earlier work showing the need for explicit and detailed reporting of methods when the friction cost approach is used [26].

A research agenda

As a result of this review, it is important to highlight (1) the need for increased transparency in the way the friction cost method is applied to ensure reliable productivity cost outcomes, and (2) the need to generate country-specific friction cost approach parameter estimates. Even within studies from the same country, there is huge heterogeneity in the methods employed, with many different parameter values being applied without clear referencing/reporting. It is clear that there is no consensus on the sources for practical data across different countries. This area could benefit from further research to obtain more recent and appropriate data needed for the application of this method. One way forward is to establish guidance on a reference case of methods and data sources when using the friction cost approach tailored to specific country settings, and/or reporting guidelines for using the friction cost approach.

Further research drawing on existing best practice needs to be undertaken to generate the following country-specific practical data: (1) vacancy durations in order to generate length of friction estimates, including stratified friction periods by, for example, occupational classifications; (2) elasticity for labour time versus labour productivity, termed as elasticity factor herein; and (3) standard friction cost approach productivity costs per day/hour. Generating country-specific evidence on these parameters will enable improved application of this approach in different country contexts. Clear reporting of data for key variables specific to the friction cost approach that vary across countries, such as the friction period, is also important and would promote more transparency. Finally, further research is needed to determine appropriate methods for applying the friction cost approach to valuing productivity costs in the area of reduced productivity at work (presenteeism) [72] and the cost implications of incorporating wage-related multiplier effects when estimating productivity costs [73]. Presenteeism costs are often excluded from economic evaluation studies, although they have been shown to be significantly higher than absenteeism [74, 75].

Conclusion

Theory and literature to support estimation of productivity costs using the friction cost approach do not appear to have widely permeated applied economic costing literature in countries outside the Netherlands. Most of the studies that have estimated productivity costs using the friction cost approach were found to have been in the Netherlands, and in some cases when applied elsewhere, parameters specific to the Netherlands were employed as opposed to parameters specific to the country of study. The methods used varied widely in the level of detail reported and in the quality of valuation methods. To enable increased application of this method more widely, and to ensure realistic valuation approaches, data for specific country contexts are necessary to more accurately estimate true economic productivity costs for the purpose of societal economic evaluation. Overall, more attention needs to be given to the reporting of methods used to estimate productivity costs using the friction cost approach.

References

Knies, S., et al.: The transferability of valuing lost productivity across jurisdictions. Differences between national pharmacoeconomic guidelines. Value Health 13(5), 519–527 (2010)

Johannesson, M.J., Jönsson, B., Jönsson, L., Kobelt, G., Zethraeus, N.: Why should economic evaluations of medical innovations have a societal perspective? OHE Briefing, No. 51, Office of Health Economics, London (2009)

Gold, M., et al.: Cost-effectiveness in Health and Medicine. Oxford University Press, New York (1996)

Byford, S., Raftery, J.: Perspectives in economic evaluation. BMJ 316(7143), 1529–1530 (1998)

Drummond, M., et al.: Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes. Oxford University Press, New York (1996)

Brouwer, W.B., Koopmanschap, M.A., Rutten, F.F.: Productivity costs measurement through quality of life? a response to the recommendation of the Washington Panel. Health Econ. 6(3), 253–259 (1997)

Olsen, J.A., Richardson, J.: Production gains from health care: what should be included in cost-effectiveness analyses? Soc. Sci. Med. 49(1), 17–26 (1999)

Bojke, L., et al.: Capturing all of the costs in NICE appraisals: the impact of inflammatory rheumatic diseases on productivity. Rheumatology 51(2), 210–215 (2012)

Sculpher, M.: The role and estimation of productivity costs in economic evaluation. In: Drummond, M.F., McGuire, A. (eds.) Economic Evaluation in Health Care: Merging Theory with Practice, pp. 94–112. Oxford University Press, Oxford ((2001))

Liljas, B.: How to calculate indirect costs in economic evaluations. Pharmacoeconomics 13(1 Pt 1), 1–7 (1998)

Brouwer, W.B.F., Koopmanschap, M.A.: The friction-cost method : replacement for nothing and leisure for free? Pharmacoeconomics 23(2), 105–111 (2005)

Koopmanschap, M.A., et al.: The friction cost method for measuring indirect costs of disease. J. Health Econ. 14(2), 171–189 (1995)

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: Guide To The Methods Of Technology Appraisal, (NICE) (2013)

Norwegian Medicine Agency. (NMA): Norwegian Guidelines for Pharmacoeconomic Analysis in Connection with Applications for Reimbursement. Department for Pharmacoeconomics, Ministry of Health and Social Affaires, Oslo (2005)

von der GrafSchulenberg, J.G., Jost, W., Jost, F., et al.: German recommendations on health economic evaluation: third and updated version of the Hanover Consensus. Value Health 11, 539 (2008)

Zorgverzerkeringen, C.V.: Guidelines for Pharmacoeconomic Research, Updated Version. Diemen. College voor Zorgverzekeringen (CVZ), The Netherlands (2006)

The Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (AMCP): Format For Formulary Submissions. Version 3.1. (2012)

PBAC Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee. Department of Health and Ageing, Australian Government http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/health-pbs-general-pubs-pharmpac-gusubpac.htm. (2008)

CADTH, Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH). Guidelines for the Economic Evaluation of Health Technologies: Canada. Ottawa: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. 2006

van den Hout, W.B.: The value of productivity: human-capital versus friction-cost method. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 69, i89–i91 (2010)

Fautrel, B., et al.: Costs of rheumatoid arthritis: new estimates from the human capital method and comparison to the willingness-to-pay method. Med. Decis. Mak. 27(2), 138–150 (2007)

Koopmanschap, M.A., van Ineveld, B.M.: Towards a new approach for estimating indirect costs of disease. Soc. Sci. Med. 34(9), 1005–1010 (1992)

Koopmanschap, M.A., Rutten, F.F.H.: A practical guide for calculating indirect costs of disease. Pharmacoeconomics 10(5), 460–466 (1996)

Johannesson, M., Karlsson, G.: The friction cost method: a comment. J. Health Econ. 16(2), 249–255 (1997)

Tranmer, J.E., et al.: Valuing patient and caregiver time: a review of the literature. Pharmacoeconomics 23(5), 449–459 (2005)

Pritchard, C., Sculpher, M.: Productivity Costs: Principles and Practise in Economic Evaluation. Office of Health Economics, London (2000)

Lewis, M., et al.: An economic evaluation of three physiotherapy treatments for non-specific neck disorders alongside a randomized trial. Rheumatology (Oxford) 46(11), 1701–1708 (2007)

Gray, A.M., et al.: Applied methods of cost-effectiveness analysis in healthcare. In: Gray, A.M., et al. (eds.) Handbooks in Health Economic Evaluation, vol. 3. Oxford University Press, New York (2010)

McEachan, R., et al.: Testing a workplace physical activity intervention: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 8(1), 29 (2011)

Luengo-Fernandez, R., et al.: Cost of cardiovascular diseases in the UK. Heart 92, 1384–1389 (2006)

Liu, J.L.Y., et al.: The economic burden of coronary heart disease in the UK. Heart 88(6), 597–603 (2002)

RiveroArias, O., Gray, A., Wolstenholme, J.: Burden of disease and costs of aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage (aSAH) in the United Kingdom. Cost Eff. Resour. Alloc. 8(1), 6 (2010)

Saka, M., McGuire, A., Wolfe, C.: Cost of stroke in the United Kingdom. Age Ageing 38(1), 27–32 (2009)

Huscher, D., et al.: Cost of illness in rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus in Germany. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 65(9), 1175–1183 (2006)

Ponto, K.A., et al.: Public health relevance of Graves’ orbitopathy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 98(1), 145–152 (2013)

Van Tubergen, A., et al.: Cost effectiveness of combined spa-exercise therapy in ankylosing spondylitis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 47(5), 459–467 (2002)

Hanley, N., Ryan, M., Wright, R.: Estimating the monetary value of health care: lessons from environmental economics. Health Econ. 12(1), 3–16 (2003)

Neovius, K., et al.: Lifetime productivity losses associated with obesity status in early adulthood: a population-based study of Swedish men. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 10(5), 309–317 (2012)

Oliva, J., et al.: Indirect costs of cervical and breast cancers in Spain. Eur. J. Health Econ. 6, 309–313 (2005)

Soegaard, R., et al.: Circumferential fusion is dominant over posterolateral fusion in a long-term perspective––cost-utility evaluation of a randomized controlled trial in severe, chronic low back pain. Spine 32(22), 2405–2414 (2007)

Gallefoss, F., Bakke, P.S.: Cost-benefit and cost-effectiveness analysis of self-management in patients with COPD–a 1-year follow-up randomized, controlled trial. Respir. Med. 96(6), 424–431 (2002)

Kaitelidou, D., et al.: Economic evaluation of hemodialysis: implications for technology assessment in Greece. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 21(1), 40–46 (2005)

Rutten-van Molken, M.P., et al.: A 1-year prospective cost-effectiveness analysis of roflumilast for the treatment of patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Pharmacoeconomics 25(8), 695–711 (2007)

Goossens, M.E., et al.: Health economic assessment of behavioural rehabilitation in chronic low back pain: a randomised clinical trial. Health Econ. 7(1), 39–51 (1998)

Hutubessy, R.C., et al.: Indirect costs of back pain in the Netherlands: a comparison of the human capital method with the friction cost method. Pain 80(1–2), 201–207 (1999)

Jellema, P., et al.: Low back pain in general practice: cost-effectiveness of a minimal psychosocial intervention versus usual care. Eur. Spine J. 16(11), 1812–1821 (2007)

Steenstra, I.A., et al.: Economic evaluation of a multi-stage return to work program for workers on sick-leave due to low back pain. J. Occup. Rehabil. 16(4), 557–578 (2006)

Luijsterburg, P.A., et al.: Cost-effectiveness of physical therapy and general practitioner care for sciatica. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 32(18), 1942–1948 (2007)

Maniadakis, N., Gray, A.: The economic burden of back pain in the UK. Pain 84(1), 95–103 (2000)

van der Roer, N., et al.: Economic evaluation of an intensive group training protocol compared with usual care physiotherapy in patients with chronic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 33(4), 445–451 (2008)

Bosmans, J.E., et al.: Cost-effectiveness of interpersonal psychotherapy for elderly primary care patients with major depression. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 23(4), 480–487 (2007)

van Roijen, L.H., et al.: Cost-utility of brief psychological treatment for depression and anxiety. Br. J. Psychiatry 188, 323–329 (2006)

Hakkaart-van Roijen, L., et al.: The societal costs and quality of life of patients suffering from bipolar disorder in the Netherlands. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 110(5), 383–392 (2004)

Smit, F., et al.: Cost-effectiveness of preventing depression in primary care patients: randomised trial. Br. J. Psychiatry 188, 330–336 (2006)

Stant, A.D., et al.: Cost-effectiveness of cognitive self-therapy in patients with depression and anxiety disorders. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 117(1), 57–66 (2008)

Hanly, P., et al.: Breast and prostate cancer productivity costs: a comparison of the human capital approach and the friction cost approach. Value Health 15(3), 429–436 (2012)

Brouwers, E.P., et al.: Cost-effectiveness of an activating intervention by social workers for patients with minor mental disorders on sick leave: a randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Public Health 17(2), 214–220 (2007)

Borghouts, J.A.J., et al.: Cost-of-illness of neck pain in The Netherlands in 1996. Pain 80(3), 629–636 (1999)

van den Hout, W.B., et al.: Cost-utility analysis of treatment strategies in patients with recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. Arthritis Care Res. 61(3), 291–299 (2009)

Van Schayck, C.P., et al.: The cost-effectiveness of antidepressants for smoking cessation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients. Addiction 104(12), 2110–2117 (2009)

Oostenbrink, J.B., Koopmanschap, M.A., Rutten, F.F.: Standardisation of costs: the Dutch manual for costing in economic evaluations. Pharmacoeconomics 20(7), 443–454 (2002)

Nicholson, S., et al.: Measuring the effects of work loss on productivity with team production. Health Econ. 15(2), 111–123 (2006)

Krol, M., et al.: Productivity cost calculations in health economic evaluations: correcting for compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects. Soc. Sci. Med. 75(11), 1981–1988 (2012)

Jacob-Tacken, K.H.M., et al.: Correcting for compensating mechanisms related to productivity costs in economic evaluations of health care programmes. Health Econ. 14(5), 435–443 (2005)

De Bruijn, C., et al.: Cost-effectiveness of an education and activation program for patients with acute and subacute shoulder complaints compared to usual care. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 23(1), 80–88 (2007)

Brunenberg, D.E., et al.: Joint recovery programme versus Usual Care: an economic evaluation of a clinical pathway for joint replacement Surgery. Med. Care 43(10), 1018–1026 (2005)

Liem, M.S., et al.: Cost-effectiveness of extraperitoneal laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair: a randomized comparison with conventional herniorrhaphy. Coala trial group. Ann. Surg. 226(6), 668–675 (1997). Discussion 675–6

Steuten, L.M.G., Bruijsten, M., Vrijhoef, H.J.M.: Economic evaluation of a diabetes disease management programme with a central role for the diabetes nurse specialist. Eur. Diabet. Nurs. 4(2), 64–71 (2007)

Koopmanschap, M.A., et al.: An overview of methods and applications to value informal care in economic evaluations of healthcare. Pharmacoeconomics 26(4), 269–280 (2008)

Goodrich, K., Kaambwa, B., Al-Janabi, H.: The inclusion of informal care in applied economic evaluation: a review. Value Health 15(6), 975–981 (2012)

Tan, S.S., et al.: Update of the Dutch manual for costing in economic evaluations. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 28(02), 152–158 (2012)

Kigozi, J., et al.: Construct validity and responsiveness of the single-item presenteeism question in patients with lower back pain for the measurement of presenteeism. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 39(5), 409–416 (2014)

Zhang, W., et al.: Development of a composite questionnaire, the valuation of lost productivity, to value productivity losses: application in rheumatoid arthritis. Value Health 15(1), 46–54 (2012)

Braakman-Jansen, L.M.A., et al.: Productivity loss due to absenteeism and presenteeism by different instruments in patients with RA and subjects without RA. Rheumatology 51(2), 354–361 (2012)

Ricci, J.A., Chee, E.: Lost productive time associated with excess weight in the U.S. workforce. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 47(12), 1227–1234 (2005)

Dirksen, C.D., et al.: Cost-effectiveness of open versus laparoscopic repair for primary inguinal hernia. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 14(03), 472–483 (1998)

van Eijsden, M.D., et al.: Cost-effectiveness of postural exercise therapy versus physiotherapy in computer screen-workers with early non-specific work-related upper limb disorders (WRULD); a randomized controlled trial. Trials (Electronic Resour) 10, 103 (2009)

Korthals-de Bos, I.B., et al.: Cost effectiveness of physiotherapy, manual therapy, and general practitioner care for neck pain: economic evaluation alongside a randomised controlled trial. BMJ 326(7395), 911 (2003)

Mol, B.W., et al.: Treatment of tubal pregnancy in the Netherlands: an economic comparison of systemic methotrexate administration and laparoscopic salpingostomy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 181(4), 945–951 (1999)

Nikken, J.J., et al.: Acute peripheral joint injury: cost and effectiveness of low-field-strength MR imaging–results of randomized controlled trial. Radiology 236(3), 958–967 (2005)

Poley, M.J., et al.: The cost-effectiveness of neonatal surgery and subsequent treatment for congenital anorectal malformations. J. Pediatr. Surg. 36(10), 1471–1478 (2001)

Steuten, L., et al.: Evaluation of a regional disease management programme for patients with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 18(6), 429–436 (2006)

van Enckevort, P.J., et al.: Lifetime costs of lung transplantation: estimation of incremental costs. Health Econ. 6(5), 479–489 (1997)

Vijgen, S.M., et al.: An economic analysis of induction of labour and expectant monitoring in women with gestational hypertension or pre-eclampsia at term (HYPITAT trial). BJOG 117(13), 1577–1585 (2010)

Acknowledgments

Jesse Kigozi was supported by the Arthritis Research UK Primary Care Centre (Doctoral Research Award in the area of economics of back pain) as part of a National Institute for Health Research programme of work funded through Keele University. The publication of this work is independent of the supporter’s approval or censorship of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no other financial relationships to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kigozi, J., Jowett, S., Lewis, M. et al. Estimating productivity costs using the friction cost approach in practice: a systematic review. Eur J Health Econ 17, 31–44 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-014-0652-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-014-0652-y

Keywords

- Friction cost approach

- Friction period

- Presenteeism

- Reduced productivity

- Productivity costs

- Economic evaluation