Abstract

Introduction

Delayed graft function (DGF) is considered a risk factor for rejection after kidney transplantation (KTx). Clinical guidelines recommend weekly allograft biopsy until DGF resolves. However, who may benefit the most from such an aggressive policy and when histology should be evaluated remain debated.

Methods

We analyzed 223 biopsies in 145 deceased donor KTx treated with basiliximab or anti-thymocyte globulin (rATG) and calcineurin inhibitor-based maintenance. The aim of the study was to assess the utility and safety of biopsies performed within 28 days of transplant. Relationships between transplant characteristics, indication, timing, and biopsy-related outcomes were evaluated.

Results

Main indication for biopsy was DGF (87.8%) followed by lack of improvement in graft function (9.2%), and worsening graft function (3.1%). Acute tubular necrosis was the leading diagnosis (89.8%) whereas rejection was detected in 8.2% specimens. Rejection was more frequent in patients biopsied due to worsening graft function or lack of improvement in graft function than DGF (66.7% vs. 3.5%; P = 0.0075 and 33.3% vs. 3.5%; P = 0.0104, respectively) and in biopsies performed between day 15 and 28 than from day 0 to 14 (31.2% vs. 3.7%; P = 0.0002). Complication rate was 4.1%. Management was affected by the information gained with histology in 12.2% cases (7% considering DGF).

Conclusions

In low-immunological risk recipients treated with induction and calcineurin inhibitors maintenance, protocol biopsies obtained within 2 weeks of surgery to rule out rejection during DGF do not necessarily offer a favourable balance between risks and benefits. In these patients, a tailored approach may minimize complications thus optimizing results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the last two decades, the overwhelming discrepancy between available donors and patients on the transplant waiting list has heralded an increased utilization of expanded-criteria donation after brain death (DBD) and donation after circulatory death (DCD) kidneys [1, 2]. Even though several studies have demonstrated that renal transplants performed using such organs offer acceptable long-term outcomes [2,3,4], it is well known that they have a greater risk of primary non-function (PNF), delayed graft function (DGF), and rejection than standard-criteria DBD [5,6,7]. With these assumptions, it is reasonable to expect that DGF rates will rise significantly in the future.

Main predisposing factors for DGF are DCD donor, donor age, cold and warm ischemia time, dialysis vintage, and recipient sensitization [8]. Differential diagnosis is challenging because in the early post-transplant phase many conditions may present with low urinary output and impaired renal function. Doppler-ultrasound and contrast-enhanced computed tomography evaluation of the allograft allows to detect urological and vascular complications. However, imaging and standard laboratory tests are mostly unable to clarify the underlying cause of DGF. For these reasons, prolonged DGF usually prompts a kidney biopsy to rule out rejection, thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA), drug-related nephrotoxicity or recurrent primary renal disease [9]. Albeit generally safe, a transplant biopsy in the first weeks after surgery is not without risk [10]. Recent manipulation of the allograft and anticoagulation for deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis may increase biopsy-related complications. Modern immunosuppressive protocols have significantly reduced acute rejection rates within 6 months of transplant [11]. This is especially true for non-sensitized patients receiving a standard-criteria DBD kidney [12]. Early biopsy in this subset of recipients might have limited diagnostic yield and, therefore, it could represent an unnecessary risk.

Our aim was to assess the utility and safety of early biopsy in a recent cohort of deceased donor kidney transplants (KTx).

Methods

Study design

In this single-centre retrospective study with 1-year follow-up, we analyzed data from patients undergoing deceased donor KTx between January 2010 and December 2013 at the Royal London Hospital (London, UK). Exclusion criteria were: (1) recipient age < 18 years; (2) induction other than basiliximab or rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin (rATG); and (3) maintenance other than tacrolimus or cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), and steroid. Donor data, organ details, recipient characteristics, allograft histology, and transplant-related outcomes were prospectively recorded in a central database by dedicated staff (as per standard practice at our institution) and reviewed by the authors. For analysis purpose, transplants were sorted in different sub-categories according to donor type (DBD vs. DCD), donor age (< 60 years vs. ≥ 60 years), induction (basiliximab vs. rATG), and immunological risk (low-risk vs. high-risk). Transplants were defined as low-immunological risk if all the following conditions were met: (1) de novo recipient; (2) last panel-reactive antibody (PRA) status < 50%; (3) undetectable donor-specific antibody (DSA); and (4) donor-recipient human leukocyte antigen (HLA) mismatch < 4.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was to assess the utility of allograft biopsy performed within 28 days of transplant (early biopsy). As utility measure we considered the ability of the information obtained with histology to change the clinical management. Such a parameter was evaluated as an overall outcome and as a specific outcome for different clinical settings (DGF vs. worsening graft function vs. lack of improvement in graft function), transplant sub-categories (DBD vs. DCD, donor < 60 years vs. donor ≥ 60 years, low-immunological risk vs. high-immunological risk, basiliximab vs. rATG), and post-transplant periods (post-operative day 0–14 vs. post-operative day 15–28). Indications for early biopsy were: (1) DGF (need for dialysis during the first week after surgery); (2) worsening graft function (increase in serum creatinine ≥ 20% from nadir); and (3) lack of improvement in graft function (serum creatinine unchanged or decreased < 10% for 3 consecutive days). The following secondary endpoints were evaluated: safety of early biopsy, agreement between clinical and pathological diagnoses, and biopsy-proven rejection within 28 days of transplant (early rejection). Possible relationships between donor type, donor age, induction, immunological risk, and biopsy-related outcomes were also investigated. Safety was assessed considering the complications caused by the procedure. Rejection was suspected for serum creatinine increase ≥ 20% from nadir and always confirmed by histology [13]. Borderline, grade-I, and grade-IIA cell-mediated rejections (CMR) were treated with intravenous methylprednisolone 500 mg/day for 3 days. Grade-IIB and grade-III CMR were treated with intravenous rATG 1.5 mg/kg/day for 4 days. Antibody-mediated rejection (AMR) was treated with intravenous steroid, intravenous immunoglobulin, and plasma exchange. Histology was considered positive for acute tubular necrosis (ATN) if any evidence of acute tubular injury was mentioned in the report (without regard to severity). Polyomavirus-associated nephropathy was suspected in case of persistent (> 21 days) BK-virus plasma polymerized chain reaction (PCR) ≥ 10,000 copies/mL [14]. Protocol biopsies were obtained between 3 and 6 months after surgery in patients with a previous transplant failed due to rejection or calcineurin inhibitor (CNI)-related nephrotoxicity, early biopsy-proven rejection, serum creatinine persistently > 2 mg/dL, and de novo DSA. Biopsies were performed bed-side under ultrasound guidance using a 16-gauge automatic biopsy needle and evaluated by two expert renal pathologists. Before the procedure, patients were assessed with coagulation and platelet function tests. Specimens were embedded in paraffin, stained with H&E and PAS, and checked with immunohistochemistry for C4d and SV40. Histology was assessed using Banff 2007 classification [15]. Renal function was measured by estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) according to the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) formula [16].

Immunosuppression

As induction, patients received intravenous basiliximab (Simulect®, Novartis, Basel, Switzerland) 20 mg on days 0 and day 4 or rATG (Thymoglobulin®, Genzyme, Cambridge, MA, USA) 4 mg/kg total-dose at day 0 and day 4. Participants were also given intravenous methylprednisolone 500 mg on day 0, 250 mg on day 1, and 125 mg on day 2. As maintenance, a triple-agent CNI based scheme was administered. From day 0, patients orally received tacrolimus (Adoport®, Novartis, Basel, Switzerland) 0.15 mg/kg/day or cyclosporine (Neoral®, Novartis, Basel, Switzerland) 7 mg/kg/day, and MMF (Myfenax®, Teva, Petach Tikva, Israel) 2000 mg/day. Tacrolimus dose was adjusted to achieve a trough level of 8–10 ng/mL during the first month and 6–8 ng/mL thereafter whereas cyclosporine dose was adjusted to achieve a trough level of 200 ng/mL during the first month and 100–150 ng/mL thereafter. From day 3, patients received oral prednisone 20 mg/day, progressively tapered to 5 mg/day after 1 month.

Concomitant medications

Recipients were given prophylaxis for Pneumocystis jirovecii (oral trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole 80 + 400 mg 3 times a week for 3 months). Patients at increased risk of Cytomegalovirus (CMV) disease (i.e. recipient negative CMV immunization with donor positive CMV immunization, rATG induction or anti-rejection treatment) received oral valganciclovir (dose titrated according to renal function) for 6 months. As deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis, participants were given subcutaneous tinzaparin 175 anti-Xa IU/kg/day up to post-operative day 28.

Statistical analysis

Categorical and numerical variables were described using proportions, medians, and first–third interquartile ranges (IQR). Data were compared using Fisher’s exact test, Chi-square test or Mann–Whitney U test as appropriate. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to analyze patient survival, graft survival, and rejection rates. Curves were compared with log-rank test. Significance was defined as P value < 0.05. We ran analyses with SPSS 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, USA).

Results

Patient demographics and characteristics

From January 2010 to December 2013, 282 patients have undergone deceased donor KTx at our centre. 270 participants were enrolled into the study. Reasons for exclusion were: daclizumab induction (n = 2), immunoglobulin induction (n = 1), alemtuzumab induction (n = 2), azathioprine maintenance (n = 5), and steroid-free maintenance (n = 2). The cohort included 171/270 (63.3%) DBD and 99/270 (36.7%) DCD recipients. Main ethnic groups were Caucasian (102/270, 37.8%) and Afro-Caribbean (52/270, 19.3%). Median recipient and donor age were 50 (IQR 39–57) and 51 (IQR 39–61) years, respectively. As induction, 141/270 (52.2%) patients received rATG whereas 129/270 (47.8%) basiliximab. All participants were given a CNI-MMF-steroid maintenance: 186/270 (68.9%) cyclosporine and 84/270 (31.1%) tacrolimus. No recipients were lost to follow-up. Characteristics of the population are detailed in Table 1.

Transplant outcome

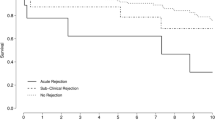

One-year patient and death-censored graft survival rates were 92.6% and 90%, respectively. There were two episodes of PNF (0.7%). DGF was recorded in 116/270 (43%) recipients with a median duration of 10 (IQR 7–13) days. One-year biopsy-proven rejection rate was 17%. Overall, we observed 55 episodes of rejection in 46 patients: 45/55 (81.8%) CMR, 4/55 (7.3%) AMR, and 6/55 (10.9%) borderline. Median time from transplant to first episode of rejection was 84 (IQR 42.75–115) days. Eight/270 (3%) patients were diagnosed rejection within 28 days of transplant. One-year median MDRD eGFR was 47 (IQR 35.8–61.9) mL/min/1.73 m2. Characteristics and outcomes of patients experiencing DGF are summarized in Table 1.

Time distribution of allograft biopsy

The flow diagram of the study is depicted in Fig. 1. During the follow-up, we performed 223 allograft biopsies in 145 recipients. Fifty-one/145 (35.2%) patients were biopsied twice or more. Adequate specimens (as per pathologist’s report) were obtained in all cases. Median time from transplant to first biopsy was 12 (IQR 8–81) days. Eighty-eight/145 (60.7%) recipients were biopsied within 28 days of transplant for a total amount of 98 (98/223, 43.9%) early biopsies; 30/98 (30.6%) in the first, 52/98 (53.1%) in the second, 9/98 (9.2%) in the third, and 7/98 (7.1%) in the 4th week after surgery. Time distribution of allograft biopsies is described in Fig. 2.

a Time distribution of kidney allograft biopsies during the first year after transplant. b Indications for early (day 0–28) or late (day 29–365) kidney allograft biopsies; DGF: need for dialysis during the first week after surgery; worsening graft function: increase in serum creatinine ≥ 20% from nadir; lack of improvement in graft function: serum creatinine unchanged or decreased < 10% for 3 consecutive days; polyomavirus viremia: persistent BK-virus plasma PCR ≥ 10,000 copies/mL; protocol histology: previous transplant failed due to rejection or CNI-related nephrotoxicity, early biopsy-proven rejection, serum creatinine persistently > 2 mg/dL, and de novo DSA

Indication for allograft biopsy

Early biopsies were performed due to DGF (86/98, 87.8%), lack of improvement in graft function (9/98, 9.2%), and worsening graft function (3/98, 3.1%). As shown in Fig. 2, indications for early or late allograft biopsies were significantly different; in particular there was a disproportionate number of procedures performed due to DGF (86/98, 87.8% vs. 1/125, 0.8%, P < 0.00001), worsening graft function (3/98, 3.1% vs. 53/125, 42.4%, P < 0.00001), protocol histology (0/98, 0% vs. 49/125, 39.2%, P < 0.00001), and polyomavirus viremia (0/98, 0% vs. 7/125, 5.6%, P = 0.0189).

Histology

Considering early biopsies, histology demonstrated: ATN (88/98, 89.8%), CMR (5/98, 5.1%), borderline rejection (3/98, 3.1%), thrombotic microangiopathy (1/98, 1%), and normal allograft (1/98, 1%). The distribution of histological diagnoses in early and late biopsies was significantly different for ATN (88/98, 89.8% vs. 36/125, 28.8%; P < 0.00001), CMR (5/98, 5.1% vs. 40/125, 32%; P < 0.00001), and polyomavirus-associated nephropathy (0/98, 0% vs. 6/125, 4.8%; P = 0.036). As shown in Fig. 3, the prevalence of ATN was significantly higher in biopsies performed from day 0 to 14 than from day 15 to 28: 79/82, 96.3% vs. 9/16, 56.2% (P = 0.000001). On the other hand, rejection (CMR, AMR, and borderline) was more frequently observed in specimens obtained between day 15 and 28 than between day 0 and 14: 5/16, 31.2% vs. 3/82, 3.7% (P = 0.0002). We matched indications for early allograft biopsy with histology findings (Fig. 4). In case of DGF, pathology demonstrated ATN (82/86, 95.3%), CMR (3/86, 3.5%), and normal allograft (1/86, 1.2%). In patients biopsied due to worsening graft function we found CMR (2/3, 66.7%) and TMA (1/3, 33.3%) whereas biopsies performed due to lack of improvement in graft function showed ATN (6/9, 66.7%) and borderline rejection (3/9, 33.3%). Recipients undergoing early biopsy due to DGF were more likely to be diagnosed ATN than recipients with worsening graft function (82/86, 95.3% vs. 0/3, 0%; P = 0.0003) or lack of improvement in graft function (82/86, 95.3% vs. 6/9, 66.7%; P = 0.0174). On the contrary, diagnosis of rejection was more frequent in patients biopsied due to worsening graft function or lack of improvement in graft function than DGF: 2/3, 66.7% vs. 3/86, 3.5% (P = 0.0075) and 3/9, 33.3% vs. 3/86, 3.5% (P = 0.0104), respectively.

Agreement between clinical diagnosis and histology

One/98 (1%) early biopsy was performed suspecting a CNI-induced TMA (worsening graft function, thrombocytopenia, elevated LDH, schistocytes on blood film, undetectable haptoglobin, and elevated Doppler resistive index). Clinical hypothesis was confirmed by histology and the graft was rescued stopping cyclosporine and administering belatacept (Nulojix®, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Uxbridge, UK). Eleven/98 (11.2%) procedures were carried out due to a clinical diagnosis of rejection (worsening graft function or lack of improvement in graft function, low CNI trough level, and elevated Doppler resistive index). Histology demonstrated ATN in 6/11 (54.5%) biopsies and confirmed rejection in 5/11 (45.5%). Rejections (2 CMR and 3 borderline) were successfully treated with intravenous steroid whereas patients with ATN did not have their treatment modified. In the remaining 86/98 (87.8%) cases, recipients were biopsied to rule out rejection during DGF. In this group, histology showed ATN in 82/86 (95.3%), rejection in 3/86 (3.5%), and normal allograft in 1/86 (1.2%) specimens. Recipients diagnosed with rejection (3 CMR) were administered intravenous steroid whereas 3/82 (3.7%) patients with ATN were treated using rATG and reduced CNI. Overall, agreement between clinical diagnosis and histology was limited to 9/98 (9.2%) matches and rejection detected in 8/98 (8.2%) reports.

Early allograft biopsy and clinical management

Treatment strategy was affected by the information gained with histology in 12/98 (12.2%) cases. Investigating possible associations between indication for allograft biopsy, timing of allograft biopsy, transplant sub-category and the primary endpoint, we found that early biopsies performed due to worsening graft function or lack of improvement in graft function were more likely to affect clinical management than those performed due to DGF: 3/3, 100% vs. 6/86, 7% (P = 0.0007) and 3/9, 33.3% vs. 6/86, 7% (P = 0.0376), respectively. The proportion of biopsies leading to treatment modification was also higher for procedures performed from day 15 to 28 than from day 0 to 14 (6/16, 37.5% vs. 6/82, 7.3%; P = 0.0008) and in patients receiving basiliximab than rATG (7/32, 21.9% vs. 5/66, 7.6%; P = 0.0428). No statistically significant differences in the primary endpoint were observed comparing DBD vs. DCD (6/48, 12.5% vs. 6/50, 12%; P = 1), standard-criteria vs. expanded-criteria (6/60, 10% vs. 6/38, 15.8%; P = 0.5289), and high-immunological risk vs. low-immunological risk (10/59, 16.9% vs. 2/39, 5.1%; P = 0.0805) transplants. Neither episodes of early rejection nor biopsies leading to treatment modification were recorded among low-immunological risk recipients treated with rATG.

Biopsy-related complications

We observed five biopsy-related complications (5/223 procedures, 2.2%): haematuria requiring bladder catheterization (n = 1), haematuria requiring transfusion (n = 2), peri-graft haematoma requiring embolization (n = 1), and retroperitoneal haematoma requiring surgical exploration (n = 1). Eighty percent (4/5) of the complications were associated with early biopsies (4/98, 4.1%). Complication rate was significantly higher for procedures performed within 2 weeks of transplant than at a later stage: 4/82, 4.9% vs. 1/141, 0.7% (P = 0.0426).

Allograft biopsy and transplant characteristics

Outcomes of low- and high-immunological risk transplants were evaluated (Table 2). DGF rate (54/139, 38.8% vs. 62/131, 47.3%; P = 0.1770), duration of DGF (8, IQR 7–11 days vs. 10, IQR 7–14 days; P = 0.8851), and proportion of patients undergoing early biopsy (39/139, 28.1% vs. 49/131, 37.4%; P = 0.1193) were comparable. However, the early rejection rate was significantly higher in the high-risk group: 7/131, 5.3% vs. 1/139, 0.7% (P = 0.0318). More in details, a single episode of borderline rejection was recorded in the low-immunological risk group and indication for biopsy was worsening graft function. Subanalysis of DBD or DCD transplants (Online Resource 1) demonstrated that DCD recipients were more likely to develop DGF and undergo early biopsy than DBD: 52/171, 30.4% vs. 64/99, 64.6% (P < 0.00001) and 41/171, 24% vs. 47/99, 47.5% (P = 0.0001), respectively. Nevertheless, early rejection rates were similar: 4/171, 2.3% vs. 4/99, 4% (P = 0.4701). Comparison between transplants from donor < 60 and ≥ 60 years (Online Resource 2) showed that recipients of elderly kidneys had higher DGF rate (75/194, 38.7% vs. 41/76, 53.9%; P = 0.0285) and longer duration of DGF (8, IQR 6–11 days vs. 11, IQR 8–14 days; P = 0.0008) than their younger counterpart. They were also more frequently biopsied early after transplant (53/194, 27.3% vs. 35/76, 46.1%; P = 0.0039) but early rejection rates were equivalent: 5/194, 2.6% vs. 3/76, 3.9% (P = 0.6906). Analysis of induction protocols (Online Resource 3) showed that the proportion of patients experiencing DGF or undergoing early allograft biopsies was significantly higher in rATG than basiliximab: 77/141, 54.6% vs. 39/129, 30.2% (P = 0.0001) and 57/141, 40.4% vs. 31/129, 24% (P = 0.0044), respectively. Early rejection rates were similar: 5/141, 3.5% vs. 3/129, 2.3% (P = 0.7247).

Discussion

Persistent shortages of organs have compelled the transplant community to stretch criteria for organ donation and acceptance [17]. Characteristics of patients on the national waiting list have also changed. More than 20% of all KTx candidates are now older than 60 years [18, 19] while about 30% are hard-to-match due to difficult blood group or previous sensitization [20]. Wise use of organ allocation strategies and implementation of organ reconditioning techniques have allowed to optimize outcomes of renal transplants from marginal donors [3, 21, 22]. Nevertheless, both expanded-criteria DBD and DCD kidneys, especially in elderly or highly sensitized recipients, deserve special consideration on how to manage the greater risk of DGF associated with these organs [5,6,7, 23, 24].

We evaluated the utility and safety of allograft biopsies performed within 4 weeks of transplant in a contemporary cohort of deceased donor KTx. To reduce bias and increase generalizability, we focused on patients treated with basiliximab or rATG and a CNI-MMF-steroid maintenance.

In this series, DGF was the leading indication for early biopsy (88%), followed by lack of improvement in graft function (9%) and worsening graft function (3%). ATN was the most frequent diagnosis (90%) whereas signs of rejection were detected in only 8% of the specimens. Matching indication for early biopsy with histology, we found that patients biopsied due to worsening graft function or lack of improvement in graft function were more likely to be diagnosed rejection than those with DGF (67% vs. 33% vs. 3.5%). Furthermore, analysis of time-dependent distribution of histological diagnoses demonstrated that the chance of finding rejection was significantly higher for biopsies performed between day 15 and 28 than those obtained at an earlier stage after transplant (31.2% vs. 3.7%).

Our results are in contrast with other studies reporting acute rejection rates of 30% in patients with DGF [25] and as high as 25% in recipients with adequate graft function biopsied within 10 days of transplant [26]. A reasonable explanation is that we routinely use rATG induction in sensitized recipients (previous transplant, PRA ≥ 50%, detectable DSA) and in transplants deemed at greater risk of DGF such as DCD and expanded-criteria DBD [27,28,29]. All patients included in the analysis also received a standard-dose CNI-MMF-steroid maintenance since day 0 [9]. The majority of the studies describing the outcome of early allograft biopsy in patients with DGF, refers to data collected more than 15 years ago, when trends in induction treatment were in favour of high-dose steroid or anti-IL-2 receptor antagonists and tacrolimus or MMF were not considered standard maintenance immunosuppressant [30,31,32,33]. In the last two decades, the widespread use of lymphocyte-depleting agents and tacrolimus-MMF immunosuppressive schemes has undoubtedly led to a significant reduction of early acute rejection rates [30, 32]. Management of DGF has also evolved [34]. As a consequence, we must consider the possibility that past literature may not be representative of current clinical practice. More recent analyses in recipients with or without DGF, support this point of view and in line with our study show much lower incidences of acute rejection than previously reported [35,36,37,38].

Most authors recommend weekly allograft biopsies until DGF is resolved [9]. However, the exact timing of histologic assessment during DGF is yet to be determined. As previously suggested by Ortiz et al. [37] and Kikik et al. [38], we demonstrated that in patients receiving induction and standard-dose CNI, the diagnostic yield of allograft biopsies performed within 14 days of surgery is extremely low. Moreover, direct comparison between the proportion of patients with DGF who actually benefited from histologic diagnosis of rejection in the first 2 post-transplant weeks (3.7%) and the proportion of patients experiencing biopsy-related complications during the same period (4.9%), rises the hypothesis that the approach proposed by current guidelines may be too aggressive and more risky than beneficial. At least in low-immunological risk patients, postponing the biopsy until post-operative day 15 would probably represent a safer and more effective option for managing DGF.

According to Dominguez and colleagues, graft biopsies obtained early after transplant should lead to diagnoses resulting in changes of clinical management in about 30% of cases [39]. In our experience, treatment strategy was affected by the information gained with histology in only 12% of the patients undergoing early biopsy. Considering DGF, results were even less reassuring as only 7% of the procedures actually led to treatment modifications. In an attempt to define who may benefit the most from early histology, we analyzed DGF and biopsy-related outcomes in different transplant categories. As expected, DGF and early biopsy rates were highest for patients receiving a DCD or an expanded-criteria DBD kidney [5,6,7]. However, early rejection rates were similar between DCD and DBD donors (2.3% vs. 4%) and between donors < 60 and ≥ 60 years (2.6% vs. 3.9%). The results observed in both low- and high-immunological risk transplants also indicate that the incidence of early rejection, in patients receiving induction and full-dose CNI, is probably overestimated. As a matter of fact, no early CMR or AMR were recorded among low-immunological risk recipients and overall early rejection rate in high-immunological risk patients was only 5%. As previously mentioned, these findings can be explained by the preferential use of rATG in DCD, expanded-criteria DBD, and high-immunological risk transplants [27,28,29].

The present study was not designed to compare immunosuppressive treatments and is clearly underpowered to offer conclusive evidence supporting first-line use of rATG over basiliximab. However, as already demonstrated by our group in DCD [27, 29] and in line with recent findings from other authors in standard- and expanded-criteria DBD transplants [40], it suggests to extend indications for lymphocyte-depleting agents to all recipients at the higher spectrum of DGF and with a substantial risk of rejection-related allograft loss [41, 42]. The fact that public insurance does not cover the use of rATG for prophylaxis of acute rejection in some countries, might theoretically limit the application of this therapeutic strategy outside formal research projects. However, in Europe and in the United States, rATG represents the main induction treatment both on-label and off-label [30]. Recent Food and Drug Administration approval will further increase the proportion of patients receiving lymphocyte-depleting agents as the standard of care and will probably lead to modification of clinical guidelines in the near future [9]. Similarly, it is reasonable to expect a progressive change in the prescription pattern of immunosuppressive medications in Asia [43].

Even though DGF may not be necessarily associated with a substantial increase in early rejection rates, at least in specific sub-groups of transplant recipients, it still represents a significant complication with several prognostic implications such as more complex management of immunosuppression, prolonged hospitalization, inferior renal function, and reduced allograft survival [44]. In an attempt to predict and possibly prevent the occurrence of DGF, many scoring systems have been proposed with mixed results [45]. The use of time 0 biopsies has been also evaluated. Depending on the study considered, DGF has been associated with interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy [46], glomerulosclerosis [47], arteriosclerosis [48] or arterial hyalinosis [44]. However, given the heterogeneity of the populations included and the inconsistency of the results observed, evidence in favour of pre-implantation histology as a predictor of DGF remain weak. A recent analysis conducted at our centre in 112 controlled DCD kidney transplants, confirms this uncertainty as it failed to demonstrate any significant associations between allograft histology and DGF [29]. Due to limited supporting data [49] and lack of formal clinical guidelines, procurement biopsy is not standard practice in the UK and the vast majority of the kidneys is accepted and allocated considering clinical characteristics of both donors and recipients. To reduce organ discard rates and minimize cold ischemia time, our policy is to perform pre-implantation biopsies only if the allografts are considered at high risk of PNF (DCD ≥ 60 years, DBD ≥ 80 years, DCD or DBD with evidence of acute kidney injury at the time of organ retrieval or warm ischemia time ≥ 40 min). Therefore, information regarding pre-transplant histology for most of the patients included in the present series were not available.

In line with previous reports, the overall biopsy-related complication rate was around 2% [9]. Nevertheless, early biopsies accounted for 80% of the complications with a significant difference between procedures performed within 2 weeks of surgery and those obtained at a later stage (4.9% vs. 0.7%). As discussed above, such a finding suggests to reconsider indications for allograft biopsy in the very early post-transplant course and to reserve histologic assessment to those patients with DGF who actually have the highest change of benefiting from the procedure. Since no episodes of early rejection were recorded among low-immunological risk recipients treated with rATG, in this group of patients allograft biopsy should be probably avoided unless DGF exceeds post-operative day 28. In low-immunological risk patients receiving basiliximab, a reasonable approach would be to postpone allograft biopsy until post-operative day 15. Instead, weekly histological evaluation should be offered to all high-risk recipients with additional predisposing factors for rejection such as low CNI exposure or abnormal Doppler ultrasound findings.

Conclusions

The importance of allograft histology for diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic purposes is unquestionable. Nevertheless, our data demonstrate that biopsies obtained within 2 weeks of transplant to rule out rejection during DGF do not offer a favourable balance between risks and benefits. This is especially true for low-immunological risk patients treated with basiliximab or rATG induction and a standard-dose CNI-MMF-steroid maintenance. In this subgroup of recipients, a more conservative approach would minimize complications thus optimizing results. Prospective multi-centre studies evaluating cost-effectiveness of early biopsy in different transplant categories and immunosuppressive therapies are warranted.

References

Pérez-Sáez MJ, Montero N, Redondo-Pachón D, Crespo M, Pascual J. Strategies for an expanded use of kidneys from elderly donors. Transplantation. 2017;101:727–45.

Summers DM, Watson CJ, Pettigrew GJ, et al. Kidney donation after circulatory death (DCD): state of the art. Kidney Int. 2015;88:241–9.

Fritsche L, Horstrup J, Budde K, et al. Old for-old kidney allocation allows successful expansion of the donor and recipient pool. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:1434–9.

Querard AH, Foucher Y, Combescure C, et al. Comparison of survival outcomes between expanded criteria donor and standard criteria donor kidney transplant recipients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transpl Int. 2016;29:403–15.

Weber M, Dindo D, Demartines N, Ambühl PM, Clavien PA. Kidney transplantation from donors without a heartbeat. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:248–55.

Snoeijs MG, Winkens B, Heemskerk MB, et al. Kidney transplantation from donors after cardiac death: a 25-year experience. Transplantation. 2010;90:1106–12.

Heldal K, Leivestad T, Hartmann A, Svendsen MV, Lien BH, Midtvedt K. Kidney transplantation in the elderly—the Norwegian experience. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:1026–31.

Nashan B, Abbud-Filho M, Citterio F. Prediction, prevention, and management of delayed graft function: where are we now? Clin Transplant. 2016;30:1198–208.

Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Transplant Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the care of kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(Suppl 3):S1–S155.

Fereira LC, Karras A, Martinez F, Thervet E, Legendre C. Complications of protocol renal biopsy. Transplantation. 2004;77:1475–6.

Opelz G, Unterrainer C, Süsal C, Döhler B. Efficacy and safety of antibody induction therapy in the current era of kidney transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31:1730–8.

Gharibi Z, Ayvaci MUS, Hahsler M, Giacoma T, Gaston RS, Tanriover B. Cost-effectiveness of antibody-based induction therapy in deceased donor kidney transplantation in the United States. Transplantation. 2017;101:1234–41.

Kasiske BL, Andany MA, Danielson B. A thirty percent chronic decline in inverse serum creatinine is an excellent predictor of late renal allograft failure. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39:762–8.

Favi E, Puliatti C, Sivaprakasam R, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and outcome of BK polyomavirus infection after kidney transplantation. World J Clin Cases. 2019;7:270–90.

Solez K, Colvin RB, Racusen LC, et al. Banff 07 classification of renal allograft pathology: updates and future directions. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:753–60.

Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Roth D. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease study group. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:461–70.

NHS. Blood and Transplant. Organ Donation and Transplantation. Activity report 2016/17. https://nhsbtdbe.blob.core.windows.net/umbraco-assets-corp/4657/activity_report_2016_17.pdf. Accessed 18 Mar 2019.

Roodnat JI, Zietse R, Mulder PG, et al. The vanishing importance of age in renal transplantation. Transplantation. 1999;67:576–80.

Ponticelli C, Podestà MA, Graziani G. Renal transplantation in elderly patients. How to select the candidates to the waiting list? Transplant Rev (Orlando). 2014;28:188–92.

Holscher CM, Jackson K, Thomas AG, et al. Temporal changes in the composition of a large multicenter kidney exchange clearinghouse: do the hard-to-match accumulate? Am J Transplant. 2018;18:2791–7.

De Deken J, Kocabayoglu P, Moers C. Hypothermic machine perfusion in kidney transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2016;21:294–300.

Weissenbacher A, Hunter J. Normothermic machine perfusion of the kidney. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2017;22:571–6.

Qureshi F, Rabb H, Kasiske BL. Silent acute rejection during prolonged delayed graft function reduces kidney allograft survival. Transplantation. 2002;74:1400–4.

Jain S, Curwood V, White SA, Furness PN, Nicholson ML. Sub-clinical acute rejection detected using protocol biopsies in patients with delayed graft function. Transpl Int. 2000;13(suppl 1):S52–S5555.

Gaber LW, Gaber AO, Hathaway DK, Vera SR, Shokouh-Amiri MH. Routine early biopsy of allografts with delayed function: correlation of histopathology and transplant outcome. Clin Transplant. 1996;10:629–34.

Shapiro R, Randhawa P, Jordan ML, et al. An analysis of early renal transplant protocol biopsies–the high incidence of subclinical tubulitis. Am J Transplant. 2001;1:47–50.

Popat R, Syed A, Puliatti C, Cacciola R. Outcome and cost analysis of induction immunosuppression with IL2Mab or ATG in DCD kidney transplants. Transplantation. 2014;97:1161–5.

Koyawala N, Silber JH, Rosenbaum PR, et al. Comparing outcomes between antibody induction therapies in kidney transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:2188–200.

Favi E, Puliatti C, Iesari S, Monaco A, Ferraresso M, Cacciola R. Impact of donor age on clinical outcomes of primary single kidney transplantation from Maastricht category-III donors after circulatory death. Transplant Direct. 2018;4:e396.

Alloway RR, Woodle ES, Abramowicz D, Segev DL, Castan R, Ilsley JN, Jeschke K, Somerville KT, Brennan DC. Rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin for the prevention of acute rejection in kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2019;19(8):2252–61.

Ali H, Mohiuddin A, Sharma A, Shaheen I, Kim JJ, El Kosi M, Halawa A. Implication of interleukin-2 receptor antibody induction therapy in standard risk renal transplant in the tacrolimus era: a meta-analysis. Clin Kidney J. 2019;12(4):592–9.

Liu JY, You RX, Guo M, Zeng L, Zhou P, Zhu L, Xu G, Li J, Liu D. Tacrolimus versus cyclosporine as primary immunosuppressant after renal transplantation: a meta-analysis and economics evaluation. Am J Ther. 2016;23(3):e810–e824824.

Wagner M, Earley AK, Webster AC, Schmid CH, Balk EM, Uhlig K. Mycophenolic acid versus azathioprine as primary immunosuppression for kidney transplant recipients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;12:CD007746s.

Chapal M, Foucher Y, Marguerite M, Neau K, Papuchon E, Daguin P, Morélon E, Mourad G, Cassuto E, Ladrière M, Legendre C, Giral M. PREventing Delayed Graft Function by Driving Immunosuppressive InduCtion Treatment (PREDICT-DGF): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16:282.

Hart A, Smith JM, Skeans MA, Gustafson SK, Stewart DE, Cherikh WS, Wainright JL, Kucheryavaya A, Woodbury M, Snyder JJ, Kasiske BL, Israni AK. OPTN/SRTR 2015 annual data report: kidney. Am J Transplant. 2017;17(Suppl 1):21–116.

Hatoum HH, Patel A, Venkat KK. The Utility of Serial allograft biopsies during delayed graft function in renal transplantation under current immunosuppressive regimens. ISRN Nephrol. 2014;2014:292305.

Ortiz J, Parsikia A, Mumtaz K, Khanmoradi K, Balasubramanian M, Feyssa E, Campos S, Zaki R, Chewaproug D. Early allograft biopsies performed during delayed graft function may not be necessary under thymoglobulin induction. Exp Clin Transplant. 2012;10(3):232–8.

Kikic Z, Lorenz M, Sunder-Plassmann G, et al. Effect of hemodialysisbefore transplant surgery on renal allograft function–a pair ofrandomized controlled trials. Transplantation. 2009;88(12):1377–85.

Dominguez J, Kompatzki A, Norambuena R, et al. Benefits of early biopsy on the outcome of kidney transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:3361–3.

Ravindra KV, Sanoff S, Vikraman D, Zaaroura A, Nanavati A, Sudan D, Irish W. Lymphocyte depletion and risk of acute rejection in renal transplant recipients at increased risk for delayed graft function. Am J Transplant. 2019;19(3):781–9.

Irish WD, Ilsley JN, Schnitzler MA, Feng S, Brennan DC. A risk prediction model for delayed graft function in the current era of deceased donor renal transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2010;10(10):2279–86.

Haller J, Wehmeier C, Hönger G, Hirt-Minkowski P, Gürke L, Wolff T, Steiger J, Amico P, Dickenmann M, Schaub S. Differential impact of delayed graft function in deceased donor renal transplant recipients with and without donor-specific HLA-antibodies. Transplantation. 2019;103(9):e273–e280280.

Chang JY, Yu J, Chung BH, Yang J, Kim SJ, Kim CD, Lee SH, Lee JS, Kim JK, Jung CW, Oh CK, Yang CW. Immunosuppressant prescription pattern and trend in kidney transplantation: a multicenter study in Korea. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(8):e0183826.

Matignon M, Desvaux D, Noël LH, Roudot-Thoraval F, Thervet E, Audard V, Dahan K, Lang P, Grimbert P. Arteriolar hyalinization predicts delayed graft function in deceased donor renal transplantation. Transplantation. 2008;86:1002–5.

Michalak M, Wouters K, Fransen E, Hellemans R, Van Craenenbroeck AH, Couttenye MM, Bracke B, Ysebaert DK, Hartman V, De Greef K, Chapelle T, Roeyen G, Van Beeumen G, Emonds MP, Abramowicz D, Bosmans JL. Prediction of delayed graft function using different scoring algorithms: a single-center experience. World J Transplant. 2017;7(5):260–8.

Pokorná E, Vítko S, Chadimová M, Schück O, Ekberg H. Proportion of glomerulosclerosis in procurement wedge renal biopsy cannot alone discriminate for acceptance of marginal donors. Transplantation. 2000;69(1):36–433.

Gaber LW, Moore LW, Alloway RR, Amiri MH, Vera SR, Gaber AO. Glomerulosclerosis as a determinant of posttransplant function of older donor renal allografts. Transplantation. 1995;60(4):334–9.

Taub HC, Greenstein SM, Lerner SE, Schechner R, Tellis VA. Reassessment of the value of post-vascularization biopsy performed at renal transplantation: the effects of arteriosclerosis. J Urol. 1994;151(3):575–7.

Lentine KL, Naik AS, Schnitzler MA, Randall H, Wellen JR, Kasiske BL, Marklin G, Brockmeier D, Cooper M, Xiao H, Zhang Z, Gaston RS, Rothweiler R, Axelrod DA. Variation in use of procurement biopsies and its implications for discard of deceased donor kidneys recovered for transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2019;19(8):2241–51.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Claudio Ponticelli for kindly reviewing the manuscript before submission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research involving human participants

Treatments and procedures described in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional committee at which it was conducted and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. At the time the study was designed, it was formally discussed in a regular Multidisciplinary Research Meeting at the Royal London Hospital (London, UK) and the consensus was that Institutional Review Board approval was not necessary because it was retrospective and non-interventional. All participants were consented for both treatment and research purpose at the time of activation on the National Kidney Transplant Waiting List as per National Health Service Blood and Transplant (NHS-BT). According to Barts Health NHS Trust General Data Protection Act, General Data Protection and Regulation 2016, and Data Protection Act 2018, all subject enrolled into the study were already aware that their anonymized data including viral status as well as other biomedical parameters would have been used for research purpose. Patients who did not want their personal information to be used for planning or research were given the possibility to express their preference under National Data Opt-Out Programme.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

About this article

Cite this article

Favi, E., James, A., Puliatti, C. et al. Utility and safety of early allograft biopsy in adult deceased donor kidney transplant recipients. Clin Exp Nephrol 24, 356–368 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10157-019-01821-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10157-019-01821-7