Abstract

The pathological diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is often difficult because biopsy material may not contain pathognomonic features, making distinction between Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis and other forms of colitides a truly challenging exercise. The problem is further complicated as several diseases frequently mimic the histological changes seen in IBD. Successful diagnosis is reliant on careful clinicopathological correlation and recognising potential pitfalls. This is best achieved in a multidisciplinary team setting when the full clinical history, endoscopic findings, radiology and relevant serology and microbiology are available. In this review, we present an up-to-date evaluation of the histopathological mimics of IBD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The diagnosis of IBD is easy when characteristic/pathognomonic features are present. However, in many cases, the biopsy material does not contain the complete range of changes required for definite diagnosis. This reflects the fact that histological changes of IBD constitute a spectrum rather than the binary distinction suggested by the nomenclature of Crohn’s disease (CD) and Ulcerative colitis (UC). Cases that fall into this grey zone pose the greatest diagnostic challenge, as the features seen are not unique to IBD, and there are many other diseases which mimic the histological changes that are encountered in most cases of IBD. A proper understanding of the range of microscopic appearances of IBD and its mimics therefore is crucial to providing an accurate diagnosis. In this review, we attempt to address this question by comparing and contrasting IBD and its mimics with emphasis on potentially useful discriminatory features.

Mimics of IBD

Infections

Infection is the major differential diagnosis of IBD, and there are several well-described infections that can mimic IBD. Usually, this does not pose a significant challenge; however, difficulty arises when there is a protracted course as the delay in biopsy acquisition results in the loss of the classical characteristics of an acute infectious colitis, for example, in Campylobacter infection. The resultant resolving/chronic picture can mimic CD. It is vital to rule out infection as misdiagnosis can lead to serious complications if these patients are treated with IBD-directed therapy such as corticosteroids. In general, basal plasmacytosis, crypt distortion and an irregular mucosal surface are good discriminators of IBD over infection [1]. In cases of established IBD, in which there is a sudden unexpected flare-up of symptoms, in an otherwise disease-controlled patient, superimposed infection must always be considered. The commonest causes are CMV and Clostridium difficile [2, 3].

Intestinal tuberculosis

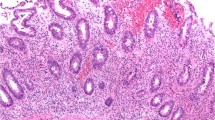

Intestinal tuberculosis (TB) favours the ileocaecal region in 90 % cases [4] with acid-fast bacilli demonstrable in approximately 50 % of cases [5]. Both CD and TB cause granulomatous inflammation [4] with macroscopic ulceration and fibrous scarring ± inflammatory mass-like lesions. The histological hallmarks of TB are large, compact epithelioid granulomas with central necrosis and Langhans giant cells surrounded by a cuff of lymphoid tissue (Fig. 1) [6]. These can become florid and confluent, whereas the granulomas seen in CD rarely have necrosis and, when present, are small and circumscribed. Intestinal TB shows asymmetric transmural thickening, a lack of fat wrapping and nodal granulomas in the absence of intramural granulomas [4, 5].

Tuberculosis (TB). A young male presented with a 2-week history of weight loss, diarrhoea and abdominal mass. Histology of the terminal ileum and caecum demonstrates extensive necrotic granulomatous inflammation with areas of caseation necrosis and multinucleated giant cells. Often the special stains do not reveal the bacilli, but negative stain does not preclude the diagnosis of TB (H&E ×10)

Yersinia

Yersinia paratuberculosis infection is also characterised by suppurative epithelioid granulomas with prominent lymphoid cuffing. Histological overlap with CD is seen with cryptitis, ±transmural lymphoid aggregates and lymphoid hyperplasia with overlying aphthous ulceration [6, 7]. Evidence of established chronicity such as crypt distortion, muscularis mucosa thickening and neural hyperplasia favours CD over Yersinia [6, 7]. Serological tests are also available clinically should further confirmation be required [5].

Amoebiasis

Endoscopically, amoebiasis (Entamoeba histolytica) may present with punctuate ulcers most commonly in the right colon and caecum, and mimics CD. Histologically, flask-shaped ulcers are seen extending into the submucosa associated with an extensive necroinflammatory exudate in an established infection. Amoebae may be identified within the exudate but may be sparse and can be overlooked (Fig. 2). In contrast to IBD, normal mucosa is present adjacent to these lesions [7] and granulomas are not a feature. Chronic infection leads to fibrosis and crypt architectural changes which can closely mimic CD [6] or UC.

Lymphogranuloma venereum

Lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) is a sexually transmitted disease cause by Chlamydia trachomatis of which serovars L1–3 can cause a proctitis that mimics IBD [1, 8, 9]. LGV proctitis is almost exclusively reported in men who have sex with men, the majority of whom are HIV-positive (70–96 %) [9]. Clinically, the presentation mimics IBD, but unlike IBD there is an associated painful inguinal lymphadenopathy which is bilateral in a third of patients [9]. Histologically, LGV proctitis is characterised by an intense lymphohistiocytic infiltrate associated with prominent plasma cells within the mucosa and submucosa [10] but minimal basal plasmacytosis. Characteristically, the associated acute inflammation is mild to moderate with cryptitis and crypt abscesses but is disproportionate to the chronic inflammatory infiltrate present. Crypt distortion and granulomas are minimal and Paneth cell metaplasia is rare [1, 8–10]. Thickening and fibrosis in chronic infections are seen which leads to rectal strictures and stenosis. Serology is not reliable, and real-time polymerase chain reaction on rectal swab specimens is the most reliable diagnostic test [8, 9].

Iatrogenic causes

Drugs including non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

The range of drugs which are known to be associated with significant gastrointestinal side effects is very large and includes potassium compounds, sodium phosphate bowel preparations, many chemotherapy agents such as adriamycin, vincristine, cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil, ergotamine derivatives, mercaptopurine, oral contraceptive pill, cannabis, methyldopa, penicillins, digoxin and parenteral gold [4, 5, 11, 12]. The majority of drug effects are usually non-specific and endoscopically appear with varying degrees of ulceration, stricture formation, inflammation and ischaemia [12]. Histological features which favour a drug aetiology include raised numbers of eosinophils, epithelial apoptosis, cytoplasmic vacuolation and increased intraepithelial lymphocytes, but none of these are conclusive [12]. Slow release preparations are particularly problematic as their nature allows them to involve the terminal ileum and caecum where they can cause local effects [13]. Immunosuppressive drugs are also important which, as well as their direct effects, can allow opportunistic infections such as CMV which may mimic IBD [12].

Less commonly described are the effects of NSAIDS on the colon that can mimic the features of IBD. The prevalence of colon-associated NSAID pathology is thought to be in the region of 0.2–0.45 % [14]. The endoscopic patterns of NSAID-related changes include mucosal ulceration and discrete, sharply demarcated ulcers that are either single or multiple [11, 13–15]. Histologically, there are no definitive features, but typically an NSAID-associated colitis will show a low number of mucosal inflammatory cells associated with ulcers, in contrast to the pattern observed in IBD. If strictures are present they often show preservation of cryptal architecture with a normal number and distribution of inflammatory cells in comparison with CD [13, 16].

Radiation colitis

Radiation colitis can be acute (within 2 weeks of exposure) or chronic (6 months to >5 years post-exposure) [6, 10]. The endoscopic appearances are of a non-specific ulcerating colitis which may be associated with strictures and fistulas, mimicking IBD. Histologically, the appearances differ depending on the type of presentation. In the acute setting, the pathology is situated in the epithelium with epithelial flattening, a prominent eosinophilic inflammatory infiltrate with formation of eosinophilic microabscesses, apoptosis and slough. Cryptal injury with or without abscesses are also seen with so-called exploding crypts. Regenerative cellular atypia can be marked and may mimic dysplasia with meganucleosis [6, 17]. In chronic disease, the pathology is centred on the vascular changes with hyalinisation, especially submucosal, arteriolar intimal proliferation and telangiectasia (Fig. 3). This may give rise to features similar to ischaemic colitis characterised by stromal fibrosis and hyalinisation with a thickened and splayed muscularis mucosa associated with crypt architectural distortion and Paneth cell metaplasia. Characteristic radiation fibroblasts are present within the hyalinised stroma [6, 10].

Chronic radiation colitis. A 74-year-old male previously treated with radiotherapy for prostate carcinoma presented with tenesmus, faecal urgency and anal pain on defecation. Histology shows distortion of crypt architecture with mucosal oedema and radiation changes. Often there is vascular telangiectasia which are the causes for rectal bleeding (H&E ×4)

It is not always possible to differentiate between ischaemic colitis and radiation colitis histologically, so knowledge of the patient’s previous history is essential in making the diagnosis especially in biopsy specimens where material is superficial and changes can be subtle [18, 19].

Ischaemia

Ischaemic colitis is most prevalent in the over 65 years age group but can also occur in younger patients, for example, as a complication of oral contraceptive pill usage or marathon running [10]. In the acute phase of the disease, there is usually not an issue with diagnosis, but in the reparative and chronic phases it may mimic changes of CD [5].

In the reparative phase, the lamina propria has a homogenous eosinophilic hyalinised appearance with haemosiderin-laden macrophages [6, 20]. Crypt withering and dropout are seen [5, 21], with a relative lack of chronic inflammatory cells. There is a notable absence of basal plasmacytosis, a feature commonly seen in CD [1, 5, 21].

In the presence of chronic ischaemia, there is progressive submucosal fibrosis with atrophic microcrypts, crypt distortion, chronic inflammation and neuroendocrine hyperplasia including Paneth cell and pseudo-pyloric gland metaplasia [1, 5, 6]. Granulomas, fissures and lymphoid follicles are absent, which may aid distinction from CD [20].

Segmental colitis associated with diverticulosis

Segmental colitis associated with diverticulosis (SCAD) is defined as “a chronic colitis that is confined to the diverticular segment in individuals with an otherwise uncomplicated diverticular disease” [22]. By definition, the rectum and proximal colon are endoscopically and histologically normal so this information is crucial when considering the diagnosis. SCAD always has a symptomatic presentation but characteristically there is no fever, leukocytosis, weight loss or nausea in contrast to the classical CD presentation [22]. SCAD is male predominant and commonest in the over 60 years age group, whereas the majority of CD diagnosis are made in women <40 years old, although a second peak of CD incidence in later life is well described.

Endoscopically and histologically, there are four different manifestations of SCAD: (1) crescentic fold disease; (2) mild to moderate UC-like; (3) Crohn’s colitis-like; and (4) severe UC-like [23, 24]. All share the fundamental endoscopic features of interdiverticular mucosal inflammation with sparing of the diverticular orifices and normal appearances of the proximal colon and rectum [5, 6, 22, 23, 25, 26]. It is crucial that these appearances are recognised endoscopically as SCAD. This is because histologically the appearances range from mild non-specific, active chronic inflammation to features indistinguishable from either UC or CD as occasionally granulomas are seen. The findings of sigmoid colitis in an older male with diverticular disease should raise the possibility that the primary diagnosis is SCAD rather than IBD. Furthermore, empiric treatment may compound the error, as SCAD often responds to treatment with 5-ASAs and corticosteroids. It is essential to biopsy the rectum in such cases as inflammation of the rectum excludes SCAD and favours IBD [25].

Non-classical features of IBD: Is it ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease?

Classical UC

UC is characterised by inflammation limited to the mucosa which is diffuse and continuous in nature (Fig. 4). Classically, the rectum is nearly always involved with a variable amount of proximal extension. Microscopically, the inflammation is transmucosal with basal plasmacytosis, crypt branching and atrophy. Crypt abscesses are commonly seen with possible granulomas related to cryptolysis. The appearances vary with duration of disease and also with treatment [1, 5, 13, 27, 28].

Ulcerative colitis. A young male underwent subtotal colectomy for pancolitis refractory to medical therapy. a Histology shows diffuse mucosal limited moderately active inflammation with cryptitis, crypt abscesses and submucosal oedema. b There are features of chronicity as evident by crypt distortion and a dense chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate deep in the lamina propria. The muscularis propria is not thickened. There are no granulomata, cytomegalovirus inclusions, dysplasia or neoplasia. This is active chronic colitis with no distinguishing histological features, and in the setting of inflammatory bowel disease, the appearances are compatible with ulcerative colitis (H&E ×2 and ×20)

Non-classical features of UC

Non-classical features of UC present another potential diagnostic pitfall. Classically, UC extends continuously from the rectum and can involve a variable length of colon. However, discontinuous disease may be seen and this finding does not exclude a diagnosis of UC [10]. Mucosal healing, particularly following topical treatment with steroid enemas, or oral anti-inflammatories, such as 5-aminosalicylic acid or steroids, can produce rectal sparing or a patchy mucosal appearance with almost complete reversion to normal [10, 14, 27–29]. Apparent rectal sparing is also recognised in fulminant UC where inflammation of the transverse colon is so severe as to make the rectum look comparatively spared. Rectal sparing is also seen in some paediatric presentations of UC.

Limited left-sided disease with an unaffected transverse colon can be associated with isolated right-sided disease in the form of a “caecal patch” of inflammation, usually sited around the periappendiceal orifice, sometimes with appendicitis or limited proximal disease of the ascending colon [30].

Backwash ileitis is thought to occur due to retrograde flow of bowel contents secondary to the ileocaecal valve being rendered incompetent by inflammation, although other factors such as infection and drugs may play a role [10, 14, 29]. It is present in <20 % of UC cases, with 94 % of these showing pancolitis [14, 29, 31]. Unlike CD ileitis, the inflammation is restricted to the first few centimetres of terminal ileum and histologically shows mild patchy neutrophil infiltration of the lamina propria, focal cryptitis/crypt abscesses and mild villous atrophy [10, 27, 28, 31].

Although primarily a colonic disease, UC can rarely be associated with inflammation in the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract, principally the stomach, in the form of focal gastritis or duodenitis. This may be the source of some confusion as until recently the presence of upper gastrointestinal involvement was regarded as a useful pointer towards a diagnosis of CD, where involvement of any of the GI tract from mouth to anus can be part of the presentation [1, 10, 32, 33].

Other features formerly thought to be the exclusive preserve of CD are now also recognised to occur, though rarely, in UC. Aphthous ulceration is seen in up to 17 % of UC resection specimens [14, 29], and up to 30–50 % of UC cases contain sparse, small epithelioid cell clusters which some regard as micro-granulomas. These are usually mucosal and associated with ruptured crypts or extravasated mucin [14, 15, 29]. On occasions “bare” multinucleated cells are seen in the lamina propria in cases of UC and should not be confused with microgranulomata in CD.

Classical CD

CD is a transmural disorder that affects the entire GI tract from mouth to anus and is associated with various extraintestinal manifestations, for example, ocular inflammation, arthritis and biliary disease. A significant part of the diagnosis is the distribution pattern of the disease which is classically patchy with skip lesions both macro- and microscopically. The terminal ileum is the most commonly involved site, and the rectum is usually spared. Perianal disease in the form of skin tags, fistulae, abscesses and blind sinus tracts is present at some point in 75 % of cases [10, 20, 21, 27–29]. Microscopically, inflammation is transmural and patchy with focal crypt architectural distortion, basal plasmacytosis and epithelioid granulomas unrelated to cryptolysis (Fig. 5).

Crohn’s disease. A middle aged male with poorly controlled CD underwent excision of a splenic flexure stricture. Histology demonstrates a transmural disease involvement with prominent mural hypertrophy and lymphoid rosary b knife-like ulceration of the mucosa and c nonnecrotic granuloma formation (H&E ×2, ×20, ×20)

Colonic limited CD (L2 subtype)

It is estimated that CD is limited to the colon in between 14 and 32 % of cases with the Montreal Classification of IBD (2005) recognising that CD limited to the colon (L2) may be a distinct subtype [34, 35]. In these colon-limited cases, usually only the superficial mucosa is involved in a UC-like pattern, with little or no submucosal or transmural inflammation. The presence of granulomas is variable. Diagnosis is usually made on colectomy specimens with other CD-associated features such as fat wrapping, granulomas, skip lesions and adhesions being variably present. Soucy et al. [34] in their study of 16 cases found that overall there were no clinical or pathological differences between colon-limited CD and classical CD, except that the mean age of onset was younger in colon-limited (23 vs. 35 years) and notably 50 % of cases of colon-limited CD had left-sided disease.

Indeterminate colitis

The Montreal Working Party on the Classification of IBD (2005) has recommended that: “the term “indeterminate colitis” should be reserved only for those cases where colectomy has been performed and pathologists are unable to make a definitive diagnosis of either CD or UC after full examination” [35]. For biopsy specimens where diagnostic uncertainty exists, the term “inflammatory bowel disease unclassified” (IBDU) should be used. Indeterminate colitis (IC) and IBDU should therefore be used as holding diagnoses, as approximately 80 % of IC cases go on to be reclassified as either CD or UC within 8 years [27–29]. It is estimated that between 1 and 15 % of cases are eventually classified as CD and more than 80 % will behave like UC [36, 37]. Within the acute colitic phase, it is well recognised that the features of UC and CD may overlap and hence the majority of cases identified as IC will be colectomy specimens from cases of fulminant colitis [36, 37].

Microscopically, in IC resection specimens there is severe ulceration with a sharp transition to normal mucosa [36] accompanied by myocytolysis, telangiectasia and fissuring. The fissures of IC are multiple, squat “V”-shaped clefts sparsely lined by inflammatory cells and are present in extensively ulcerated areas. This is in contrast to CD fissures that are fewer (1–3 per colectomy) and appear as serpiginous breaks in an intact mucosa that are lined by granulation tissue/inflammatory cells [5, 12, 27, 36]. The features which aid distinction between UC, CD and IC are shown in Table 1.

Inflammation in a diverted segment of bowel: could this be IBD?

Diversion colitis

Diversion colitis (DC) is an iatrogenic inflammatory disorder that occurs in blind ending colonic segments that have been excluded from the faecal stream for any reason, e.g. IBD, carcinoma, functional or trauma. It is usually seen 3–36 months post-diversion with an incidence of between 50 and 100 % [39].

Histologically, characteristic prominent lymphoid follicles (with or without germinal centres) are seen, which correspond to nodularity observed endoscopically [5, 14, 29, 39]. Overlying ulceration can be associated with these follicles along with atrophy and distortion of adjacent crypts [5, 10]. In the cases relating to underlying IBD, the changes should be regarded as DC rather than disease relapse in this setting [10]. Resolution of the colitis occurs within 3–6 months after re-establishment of the faecal stream [29].

Pouchitis

A diagnosis of pouchitis requires a combined clinical, endoscopic and histological correlation as most pouches show histological inflammation but are clinically asymptomatic. Risk factors for pouchitis include severe appendiceal inflammation, pancolitis and superficial fissuring ulcers [38].

Pouch biopsies can be difficult to interpret as histologically nearly all pouches undergo “colonisation”/colonic metaplasia. Superimposed CD-like changes are often present including granulomas, transmural inflammation and fissures regardless of the original pathology. For these reasons, CD should never be diagnosed on pouch material alone [5] and if there is doubt about the diagnosis, this should prompt a full review of all the previous biopsy or excision material.

Rare mimics

Intestinal lymphoma

Primary colorectal lymphomas are rare (0.2–0.6 %) occurring predominantly in males aged 50–70 years [40]. Several population-based studies have demonstrated that IBD alone is not associated with an increased risk of lymphoma but IBD therapy, particularly immunosuppressive drugs, does confer a fourfold to sixfold increased risk [41].

Endoscopically, lymphoma tends to occur in regions of active inflammation and longstanding disease [10]. Histologically, in most cases, the features are similar to nodal non-Hodgkin lymphoma, typically a low- or high-grade B cell type, and often showing evidence of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection [40, 42]. Hodgkin lymphoma is less commonly seen and usually arises in the context of CD [10].

Behçet’s disease

Behçet’s disease is a multisystemic vasculitis characterised by Behçet’s triad of uveitis, aphthous stomatitis and genital ulcers with variable involvement of joints, skin and central nervous system that primarily affects young adults, with intestinal involvement present in 1–2 % of cases. This is characterised by punched out or longitudinal ulcers which can be superficial or deep with extension into the muscularis propria [39, 43].

Graft versus host disease

The gastrointestinal tract is the most commonly affected site in graft versus host disease (GVHD) together with the skin and liver [44]. Endoscopic findings are most commonly of normal, or near normal, mucosa, but these correlate poorly with symptoms and histology. The duration of the disease governs the histological appearances that are seen. The hallmark of GVHD is epithelial cell apoptosis focused at the base of crypts with a relatively sparse mononuclear cell infiltrate (Fig. 6). So-called exploding crypt cells can be seen that contain vacuoles of karyorrhectic debris and nuclear dust [10, 44]. Chronic GVHD can mimic CD by causing crypt destruction, distortion and lamina propria fibrosis. Severe GVHD can produce crypt abscesses [44]. Diagnosis depends on clinical history, histology and laboratory findings.

Our suggested approach

The above discussion clearly shows that frequently it is histologically impossible to confidently distinguish between the mimics of IBD, and it is therefore imperative that comprehensive clinical information is available to the pathologist. This will enable them to go further than a pure morphological description and interpret the histological appearances seen in the correct context and arrive at a meaningful diagnosis.

We have developed an approach which we find useful and this is summarised in Fig. 7. Specimens are submitted with the endoscopy report and any clinical information which is available at the time, including endoscopic photographs where available. An interim, pattern-based report, including differential diagnoses, is issued by the pathologist pending further discussion at a regular clinico-pathological conference (CPC) or multidisciplinary meeting (MDM). Here the full clinical history, microbiological and any other data are available and a final diagnosis is agreed upon. The final diagnosis is reached following consultation with all relevant parties and is the combined responsibility of the CPC/MDM, including the clinician and pathologist [45, 46].

In this approach, there is no place for the term “non-specific colitis” because it has no clinical relevance and can easily confuse the treating clinician [47]. In places where CPC or MDM is not available, we designed a combined endoscopy and pathology form which when implemented improved accuracy of histopathological diagnosis by 16 %. This alternative method still falls short of our gold standard approach of a CPC/MDM-derived final diagnosis [48].

Conclusions

It is apparent that IBD shares many features in common with other diseases both histologically and endoscopically. The diagnosis of many of these diseases hinges on the quality of clinical information provided. Thus, in order to make a correct diagnosis, the histopathologist must first be familiar with these mimics and then interpret the histology in the context of other available information such as clinical history, endoscopic appearances, microbiology, serology and imaging. Misdiagnosis has a profound effect on the treatment plan in every case, and inappropriate therapy is associated with significant morbidity.

References

Feakins RM, British Society of Gastroenterology (2013) Inflammatory bowel disease biopsies: updated British Society of Gastroenterology reporting guidelines. J Clin Pathol 66:1005–1026

Domènech E, Vega R, Ojanguren I et al (2008) Cytomegalovirus infection in ulcerative colitis: a prospective, comparative study on prevalence and diagnostic strategy. Inflamm Bowel Dis 14:1373–1379

Price AB, Davies DR (1977) Pseudomembranous colitis. J Clin Pathol 30:1–12

Dilauro S, Crum-Cianflone NF (2010) Ileitis: when it is not Crohn’s disease. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 12:249–258

Shepherd NA (1991) Pathological mimics of chronic inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Pathol 44:726–733

Khor TS, Fujita H, Nagata K, Shimizu M, Lauwers GY (2012) Biopsy interpretation of colonic biopsies when inflammatory bowel disease is excluded. J Gastroenterol 47:226–248

Lamps LW (2007) Infective disorders of the gastrointestinal tract. Histopathology 50:55–63

Arnold CA, Limketkai BN, Illei PB, Montogomery E, Voltaggio L (2013) Syphilitic and lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) proctocolitis: clues to a frequently missed diagnosis. Am J Surg Pathol 37:38–46

Høie S, Knudsen LS, Gerstoft J (2011) Lymphogranuloma venereum proctitis: a differential diagnose to inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol 46:503–510

Odze RD, Goldblum JR (2014) Odze and Goldblum surgical pathology of the GI tract, liver, biliary tract and pancreas, 3rd edn. Saunders, Philadelphia

Parfitt JR, Driman DK (2007) Pathological effects of drugs on the gastrointestinal tract: a review. Hum Pathol 38:527–536

Price AB (2003) Pathology of drug-associated gastrointestinal disease. Br J Clin Pharmacol 56:477–482

Püspök A, Kiener HP, Oberhuber G (2000) Clinical, endoscopic, and histologic spectrum of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced lesions in the colon. Dis Colon Rectum 43:685–691

Yantiss RK, Odze RD (2007) Pitfalls in the interpretation of nonneoplastic mucosal biopsies in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 102:890–904

Pitt MA, Knox WF, Haboubi NY (1993) Multinucleated stromal giant cells of the colonic lamina propria in ulcerative colitis. J Clin Pathol 46:874–875

Byers RJ, Marsh P, Parkinson D, Haboubi NY (1997) Melanosis coli is associated with an increase in colonic epithelial apoptosis and not with laxative use. Histopathology 30:160–164

Haboubi NY, Schofield PF, Rowland PL (1988) The light and electron microscopic features of early and late phase radiation-induced proctitis. Am J Gastroenterol 83:1140–1144

Haboubi NY, El-Zammar O, O’Dwyer ST, James RJ (2000) Radiation bowel disease: pathogenesis and management. Colorectal Dis 2:322–329

Haboubi NY, Kaftan SM, Schofield PF (1992) Radiation colitis is another mimic of chronic inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Pathol 45:272

Md JR (2011) Rosai and Ackerman’s surgical pathology, 10th edn. Mosby, Edinburgh, New York

Gramlich T, Petras RE (2007) Pathology of inflammatory bowel disease. Semin Pediatr Surg 16:154–163

Harpaz N, Sachar DB (2006) Segmental colitis associated with diverticular disease and other IBD look-alikes. J Clin Gastroenterol 40(Suppl 3):S132–S135

Tursi A (2011) Segmental colitis associated with diverticulosis: complication of diverticular disease or autonomous entity? Dig Dis Sci 56:27–34

Tursi A, Elisei W, Brandimarte G et al (2010) The endoscopic spectrum of segmental colitis associated with diverticulosis. Colorectal Dis 12:464–470

Mann NS, Hoda KK (2012) Segmental colitis associated with diverticulosis: systematic evaluation of 486 cases with meta-analysis. Hepatogastroenterology 59:2119–2121

Kruis W, Spiller RC, Papagrigoriadis S, Engel A, Kreis ME (2012) Diverticular disease: a fresh approach to a neglected disease: preface. Dig Dis 30:5

Langner C, Magro F, Driessen A et al (2014) The histopathological approach to inflammatory bowel disease: a practice guide. Virchows Arch 464:511–527

Magro F, Langner C, Driessen A et al (2013) European consensus on the histopathology of inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 7:827–851

Yantiss RK, Odze RD (2006) Diagnostic difficulties in inflammatory bowel disease pathology. Histopathology 48:116–132

Levine A, de Bie CI, Turner D et al (2013) Atypical disease phenotypes in pediatric ulcerative colitis: 5-year analyses of the EUROKIDS Registry. Inflamm Bowel Dis 19:370–377

Haskell H, Andrews CW, Reddy SI et al (2005) Pathologic features and clinical significance of “backwash” ileitis in ulcerative colitis. Am J Surg Pathol 29:1472–1481

Lin J, McKenna BJ, Appelman HD (2010) Morphologic findings in upper gastrointestinal biopsies of patients with ulcerative colitis: a controlled study. Am J Surg Pathol 34:1672–1677

Valdez R, Appelman HD, Bronner MP, Greenson JK (2000) Diffuse duodenitis associated with ulcerative colitis. Am J Surg Pathol 24:1407–1413

Soucy G, Wang HH, Farraye FA et al (2012) Clinical and pathological analysis of colonic Crohn’s disease, including a subgroup with ulcerative colitis-like features. Mod Pathol 25:295–307

Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, Colombel J-F (2006) The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut 55:749–753

Mitchell PJ, Rabau MY, Haboubi NY (2007) Indeterminate colitis. Tech Coloproctol 11:91–96

Martland GT, Shepherd NA (2007) Indeterminate colitis: definition, diagnosis, implications and a plea for nosological sanity. Histopathology 50:83–96

Yantiss RK, Sapp HL, Farraye FA et al (2004) Histologic predictors of pouchitis in patients with chronic ulcerative colitis. Am J Surg Pathol 28:999–1006

Nielsen OH, Vainer B, Rask-Madsen J (2008) Non-IBD and noninfectious colitis. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol 5:28–39

Wong MTC, Eu KW (2006) Primary colorectal lymphomas. Colorectal Dis 8:586–591

Subramaniam K, D’Rozario J, Pavli P (2013) Lymphoma and other lymphoproliferative disorders in inflammatory bowel disease: a review. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 28:24–30

Heise W (2010) GI-lymphomas in immunosuppressed patients (organ transplantation; HIV). Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 24:57–69

Kim E-S, Chung W-C, Lee K-M et al (2007) A case of intestinal Behcet’s disease similar to Crohn’s colitis. J Korean Med Sci 22:918–922

Washington K, Jagasia M (2009) Pathology of graft-versus-host disease in the gastrointestinal tract. Hum Pathol 40:909–917

Haboubi NY, Schofield PF (1994) Large bowel biopsies in colitis: a clinicopathological collaboration. J R Soc Med 87:16–17

Haboubi NY, Schofield PF (2000) Reporting colonic mucosal biopsies in inflammatory conditions: a new approach. Colorectal Dis 2:66–72

Haboubi NY, Kamal F (2001) Non-specific colitis, is it a justifiable diagnosis? Colorectal Dis 3:263–265

Absar S, Mason J, Anjum K, Haboubi N (2006) A new combined form significantly improves accuracy of pathological diagnosis in inflammatory bowel disease in absence of the clinicopathological conference. Tech Coloproctology 10:227–232

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The work is compliant with ethical standards.

Informed consent

For this type of study formal informed consent is not required.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Woodman, I., Schofield, J.B. & Haboubi, N. The histopathological mimics of inflammatory bowel disease: a critical appraisal. Tech Coloproctol 19, 717–727 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-015-1372-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-015-1372-8