Abstract

Background

Although bone and soft tissue sarcoma is recognized as a rare cancer that originates throughout the body, few comprehensive reports regarding it have been published in Japan.

Patients and methods

Bone and soft tissue sarcomas were tabulated from the Cancer Registries at eight university hospitals in the Chugoku–Shikoku region. Prognostic factors in cases were extracted in a single facility and have been analyzed.

Results

From 2016 to 2019, 3.4 patients with bone and soft tissue sarcomas per a general population of 100,000 were treated at eight university hospitals. The number of patients who underwent multidisciplinary treatment involving collaboration among multiple clinical departments has been increasing recently. In the analysis carried out at a single institute (Ehime University Hospital), a total of 127 patients (male/female: 54/73) with an average age of 67.0 y (median 69.5) were treated for four years, with a 5-year survival rate of 55.0%. In the analysis of prognostic factors by multivariate, disease stage and its relative treatment, renal function (creatinine), and a patient’s ability of self-judgment, and a patient’s mobility and physical capability were associated with patient prognosis regarding bone and soft tissue sarcomas. Interestingly, age did not affect the patient’s prognosis (> 70 vs ≦ 70).

Conclusions

Physical and social factors may affect the prognosis of patients with bone and soft tissue sarcomas, especially those living in non-urban areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Bone and soft tissue sarcoma is recognized as a malignant tumor that occurs throughout the body, including in subcutaneous tissue, bone, and muscle, and this disease contains several pathological entries. It is also recognized that this malignancy is one of the rare cancers (fewer than 6 cases per 100,000 population) and the majority of them do not have established standard treatments. Patients with bone and soft tissue sarcoma, whose tumors cannot be removed with surgical treatment have shown very poor and lethal prognoses. Recently, for rare cancers, such as bone and soft tissue sarcoma, it has been considered better to make integrated therapeutic bases such as treatment centers and to treat patients intensively by specialists in this field. The Chugoku–Shikoku region in Japan has ten university hospitals and two cancer centers, and their institutes provide intensive cancer care for not only general cancer patients but also those with bone and soft tissue sarcoma living in several non-urban areas.

In the current study, we have focused on the treatment outcome of bone and soft tissue sarcoma in the Chugoku–Shikoku region, and discussed the prognostic factors and disease-related problems of patients with this rare cancer living in non-urban areas in Japan.

Materials and methods

Patient with bone and soft tissue sarcoma and the excluding criteria

To avoid looking at cases during the COVID-19 pandemic from January 2016 to December 2019, cases of newly diagnosed and treated de novo bone and soft tissue sarcoma were reviewed based on their electronic medical records from the Cancer Registries at eight university hospitals in the Chugoku–Shikoku region (Ehime, Kagawa, Tokushima, Kochi, Yamaguchi, Hiroshima, Okayama, and Kawasaki university hospitals). The annual frequency of incidence by histopathology was summarized. In the single institute analysis, (Ehime University Hospital), three histological types of patients, such as Ewing sarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, and gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), have been excluded as unsuitable cases for the current prognostic analysis, because these three types have different treatment strategies for each.

The Cancer Registries in the current study include patients with bone and tissue sarcoma of (#1) all diagnosed cases, (#2) patients receiving first-line treatment (first-line treatment cases), (#3) patients on watchful waiting as the first line of treatment (watchful–waiting cases), (#4) the cases detected by cancer screening (screening cases), and (#5) patients who requested hospital transfers for further treatment after first-line treatments (hospital-change cases) at eight university hospitals from January 2016 to December 2019. These cases were counted according to Multiple Primary and Histology Coding Rules in the Japanese hospital-cancer registry.

Analysis of overall survival according to several prognostic factors in Ehime University Hospital

Survival time of the cases in Ehime University Hospital was studied from the date of enrollment in any treatment in 2016 to the date of the last follow-up (at the end of 2022) or date of death for the analysis of the prognostic factors. However, this includes some patients who requested hospital transfers for further treatment after first-line treatments (hospital-change cases).

The disease stage in each patient conformed with the AJCC 8th edition Cancer Staging System. Abnormal ‘mobility and ability’ indicates the situation in which a patient is not able to go to the treatment hospital without any assistance from family members or others. Abnormal ‘ability of self-judgment (mental illness)’ indicates the situation in which the patient has some kind of dementia and the ability of decision-making in everyday life is not possible. The patient is not socially independent in other words.

Overall survival (OS) curves were calculated for each prognostic group according to the Kaplan–Meier method and analyzed using the log-rank univariate test. Fisher’s exact test and Chi-squared test were performed to detect the statistical differences among the groups. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant. Prognostic factors were subjected to univariate and multivariate analyses, using Cox’s proportional hazard model, against OS. All statistical analyses were performed using the SAS software package version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Ethics of the study

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Clinical Studies at Ehime University Graduate School of Medicine (study IRB #2,102,015), and carried out in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1995 Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in Brazil 2013). Informed consent was by the opt-out principle; we disclosed information about the study on the associated website (https://www.m.ehime-u.ac.jp/school/clinical.oncology/?page_id=25) and provided an opportunity to decline to participate in this study.

Results

Diagnosis and qualified doctors for bone and soft tissue sarcomas in Chugoku–Shikoku region

Pathological variation of patients with bone and soft tissue sarcoma treated in the Chugoku–Shikoku region in the current study period is indicated in Fig. 1. GIST and liposarcoma are the most common sarcomas, and angiosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma/malignant fibrous histiocytoma (UPS/MFH), and leimyosarcoma are the secondary common sarcomas. The annual incidence of bone and soft sarcoma in this area (659 cases annually per year from January 2016 to December 2019) is 3.4 patients per a general population of 100,000 in the current study area. This analysis indicated no incidental difference of bone and tissue sarcoma in rural areas as compared to urban areas [1]. In addition, we have examined what kinds of qualified doctors engaged with the patients with bone and soft tissue sarcoma. The majority were orthopedic surgeons with oncological qualifications. However, multidisciplinary treatment (an integrated team approach in which medical professionals and oncologists consider treatment options and care of patients) had been increasing, and it was supposed that medical oncologists might be involved in those treatments, especially in non-urban areas (Fig. 2).

Patient characteristics and the survival with bone and soft tissue sarcoma in Ehime University Hospital

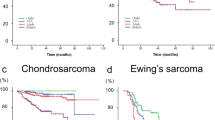

In the next study, we analyzed the prognosis of patients with bone and soft tissue sarcoma in the Chugoku–Shikoku region. This area covers a 50,725.53 km2 surface area, and has an 11,375 × 103 population. We have focused on a single prefecture, Ehime, and examined it in detail. Ehime University Hospital is located in the middle of Ehime Prefecture, which has a very long coastline dotted with about 270 islands and has many mountainous areas. This topography suggests that Ehime prefecture constitutes a typical non-urban medical environment in this country. In this analysis, we encountered one hundred twenty-seven patients with bone and soft tissue sarcoma from 2016 to 2019 in Ehime University Hospital, and the patient characteristics including their organ functions at the time of diagnosis, their treatments, and their social backgrounds are shown in Tables 1 and 2. The overall survival (OS) of a total of 127 patients is shown in Fig. 3, and the 5-year survival rate is 55.0% (Fig. 3, Supplementary data I &II).

Patient prognosis according to several patient factors such as baseline patient characteristics, organ function, treatments, and patient social background in Ehime University Hospital

Next, we performed Kaplan–Meier survival analysis to estimate the OS of the patients based on several patient factors in Ehime prefecture. Figures 4 and 5 indicate Kaplan–Meier OS curves of the currently analyzed patients (n = 127) with bone and soft tissue sarcoma according to several patient characteristics, and Tables 3 and 4 show univariate and multivariate analyses of patient-related factors. The strongest prognostic factor of patients with bone and soft tissue sarcoma living in Ehime prefecture was the disease stage, indicating that patients with bone and soft tissue sarcoma still had not received any effective and curative chemotherapeutic agents and their disease prognosis was poor without complete resection with an operative therapy (Table 3; Fig. 4). Renal function may be involved as one prognostic factor in the implementation and continuation of treatment. LDH may be involved as a tumor-related factor. Albumin and CRP level which are generally known to be related to cancer survival may be associated with patient prognosis (Table 3; Fig. 5). In addition, a patient’s mobility and physical capability also might be one prognostic factor (Table 3; Fig. 4), suggesting that it might be associated with easy access to the treatment hospital for the patients, especially for those living in non-urban areas. Patients farther from the treatment hospital and with few family supporters tended to have a worse prognosis. However, these factors were not statistically significant in the multivariate analysis (Table 4) because of the number of patients in the current study.

Interestingly, our examination did not show any statistical differences between patients with bone and soft tissue sarcoma aged 70 years or more and those younger than 70 years of age (Table 3). This result might indicate that proper treatment such as operative resection for bone and soft tissue sarcoma was leading to improvement in patient prognosis even if the patients were elderly.

Discussion

We reached two major conclusions in the current retrospective study of patients with bone and soft tissue sarcoma.

As a first conclusion, patients with bone and soft tissue sarcoma were diagnosed with a frequency of 3.4 per 100,000 population. The ratios for this rare cancer have no regional differences among urban and non-urban regions in Japan [1,2,3]. In addition, the majority of the patients had received their treatments at university hospitals and cancer centers located in their prefectures. Bone and soft tissue sarcomas had been fundamentally addressed by orthopedic oncologists. However, patients had already undergone regional consolidation and received multidisciplinary team care by specialists in major general hospitals. Increased frequency of regional consolidation seems to be an effective strategy by concentrating limited medical resources for treatment of this rare cancer [4,5,6].

Patients with rare cancers such as bone and soft tissue sarcoma are currently treated by specialists in this field by establishing treatment bases. In our study in Ehime University Hospital, factors affecting the patient’s prognosis were the disease stage, the type of treatment, and renal function as reported before [7,8,9,10]. Recently, two cytotoxic agents (eribulin and trabectedin) [11,12,13] and one small molecular compound (pazopanib) [14] have been introduced for the treatment of bone and soft tissue sarcomas. In addition, some new therapeutic agents [15, 16] are about to be introduced clinically. However, even with the introduction of new agents, our results still show no curative treatment other than surgery especially for advanced stage patients. Furthermore, analyses of other prognostic factors here suggested that the mobility and overall physical capability of the patients, number of family supporters, and the distance to the treatment hospitals had a certain impact on patient prognoses. Whether patients can easily go to the hospital depends on transportation facilities and social care systems for patients. Automobiles are one of the dominant means of transportation in non-urban arears with little public transportation available [17]. Patients living in non-urban areas need to be mobile and have some support from family members or have other social resources to continue receiving treatments. Therefore, our prognostic analyses suggest that the concentration of treatment bases in urban areas may be somewhat disadvantageous for patients with rare cancer living in non-urban areas; as a result, they may give up and discontinue their treatment.

As a second conclusion, another consideration came up in our current study. Looking at ‘real world’ data analyses for rare cancer treatment, we believe that social background is an important factor that affects treatment continuation and disease prognosis [18,19,20]. The centralization of rare cancer treatment bases in urban areas may have achieved certain positive results. However, equality in medical care is also necessary as well as centralization. From these observations, it is seen that some systems or specialists to manage rare cancers are needed even in local hospitals for patients living in non-urban areas.

One other conclusion pointed out in our study is that there is no major significance regarding a cutoff age of seventy years in relation to the prognosis of patients with bone and soft tissue sarcoma. There are several explanations for this result. First, the existence of no effective treatment for advance-staged patients other than surgery may have a strong impact on patient prognosis, more than the factor of age. Second, even if the patients were elderly, adequate multidisciplinary management and treatment might improve the prognosis of patients with bone and soft tissue sarcoma. The latter interpretation may suggest that the need for equality in medical care is as important as centralization.

Our current analysis is an observational study of a relatively moderate number of patients in a limited geographic area. We need to study more patients in the future to prove our hypothesis.

References

Ogura K, Higashi T, Kawai A (2017) Statistics of soft-tissue sarcoma in Japan: report from the Bone and Soft Tissue Tumor Registry in Japan. J Orthop Sci 22:755–764. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jos.2017.03.017

Ferrari A, Sultan I, Huang TT et al (2011) Soft tissue sarcomas across the age spectrum: a population-based study from the surveillance epidemiology and end results database. Pediatr Blood Cancer 57:943–949. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.23252

Wibmer C, Leithner A, Zielonke N et al (2010) Increasing incidence rates of soft tissue sarcomas? A population-based epidemiologic study and literature review. Ann Oncol 21:1106–1111. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdp415

Nakayama R, Mori T, Okita Y et al (2020) A multidisciplinary approach to soft-tissue sarcoma of the extremities. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 20:893–900. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737140.2020.1814150

D’Adamo DR (2011) Appraising the current role of chemotherapy for the treatment of sarcoma. Semin Oncol 38:19–29. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.seminoncol.2011.09.004

Blay JY, Sleijfer S, Schöffski P et al (2014) International expert opinion on patient-tailored management of soft tissue sarcomas. Eur J Cancer 50:679–689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2013.11.011

Bagaria SP, Wagie AE, Gray R et al (2015) Validation of a soft tissue sarcoma nomogram using a national cancer registry. Ann Surg Oncol 22:398–403. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-015-4849-9

Callegaro D, Miceli R, Bonvalot S et al (2016) Development and external validation of two nomograms to predict overall survival and occurrence of distant metastases in adults after surgical resection of localised soft-tissue sarcomas of the extremities: a retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol 17:671–680. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(16)00010-3

Sekimizu M, Ogura K, Yasunaga H et al (2019) Development of nomograms for prognostication of patients with primary soft tissue sarcomas of the trunk and extremity: report from the Bone and Soft Tissue Tumor Registry in Japan. BMC Cancer 19:657–668. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-019-5875-y

Kuntz CA, Dernell WS, Powers BE et al (1997) Prognostic factors for surgical treatment of soft-tissue sarcomas in dogs: 75 cases (1986–1996). J Am Vet Med Assoc 211:1147–1151

Schoffski P, Chawla S, Maki RG et al (2016) Eribulin versus dacarbazine in previously treated patients with advanced liposarcoma or leiomyosarcoma: a randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet 387:1629–1637. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01283-0

Demetri GD, von Mehren M, Jones R et al (2016) Efficacy and safety of trabectedin or dacarbazine for metastatic liposarcoma or leiomyosarcoma after failure of conventional chemotherapy: results of a phase III randomized multicenter clinical trial. J Clin Oncol 34:786–793. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.62.4734

Kawai A, Araki N, Sugiura H et al (2015) Trabectedin monotherapy after standard chemotherapy versus best supportive care in patients with advanced, translocation-related sarcoma: a randomised, open-label, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 16:406–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70098-7

van der Graaf WTA, Blay JY, Chawla SP et al (2012) Pazopanib for metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma (PALETTE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 379:1879–1886. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60651-5

Kyriazoglou A, Gkaralea LE, Kotsantis L et al (2022) Tyrosine kinase inhibitors in sarcoma treatment. Oncol Lett 23:183. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2022.13303

Saerens M, Brusselaers N, Rottey S et al (2021) Immune checkpoint inhibitors in treatment of soft-tissue sarcoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer 152:165–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2021.04.034

Brundisini F, Giacomini M, DeJean D et al (2013) Chronic disease patients’ experiences with accessing health care in rural and remote areas: a systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser 13:1–33

Coughlin SS (2020) Social determinants of colorectal cancer risk, stage, and survival: a systematic review. Int J Colorectal Dis 35:985–995. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-020-03585-z

Paredes TF, Canavarro MC, Simões MR (2012) Social support and adjustment in patients with sarcoma: the moderator effect of the disease phase. J Psychosoc Oncol 30:402–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347332.2012.684852

Storey L, Fern LA, Martins A, et al (2019) A critical review of the impact of sarcoma on psychosocial wellbeing. Sarcoma. 17: 9730867 https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/9730867

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the cooperation of the staff members of the chemotherapy room in Ehime University Hospital.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NN and YY carried out the design of the study, collected the clinical data, and drafted the manuscript. TF, TF, TK, KT, YS, YS, TO, TN, and MT participated in the design of the study and oversaw the clinical data. SH and SY carried out the statistical analysis of the study. YY conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read the draft, revised it critically, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

10147_2023_2453_MOESM1_ESM.jpg

Supplementary file1 (JPG 2079 KB) Supplementary data (I); Pathological incidents of bone and soft tissue sarcoma in Ehime University Hospital, data (II); With (A) or without (B) multidisciplinary treatment of patients with bone and soft tissue sarcoma in Ehime University Hospital according to treatment periods.

About this article

Cite this article

Nakamura, N., Hasebe, S., Yamanaka, S. et al. Treatments and prognostic factors for bone and soft tissue sarcoma in non-urban areas in Japan. Int J Clin Oncol 29, 345–353 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-023-02453-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-023-02453-4