Abstract

Background

Currently, no markers predictive of response to nivolumab monotherapy in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) are currently recognized in Japan. The present study was undertaken to identify such markers.

Materials and methods

Medical records of 50 patients with advanced NSCLC and treated with nivolumab monotherapy at Shizuoka Cancer Center between December 2015 and April 2016 were retrospectively reviewed. The parameters studied were age, sex, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, smoking history, histological diagnosis, epidermal growth factor receptor or anaplastic lymphoma kinase status, therapeutic line of nivolumab, efficacy of treatment immediately before nivolumab monotherapy, and time since previous therapy.

Results

The objective response rate to nivolumab monotherapy was 18% [95% confidence interval (CI) 10–31]. Multivariate logistic regression identified “squamous histology” [odds ratio (OR) 0.00054; 95% CI 0–0.27] and “response to the treatment immediately before nivolumab monotherapy” (OR 0.0011; 95% CI 0–0.092) as independently associated with response to nivolumab monotherapy.

Conclusion

“Response to the treatment immediately before nivolumab monotherapy” might be a predictive marker of response to nivolumab in patients with advanced NSCLC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Since 2000 the standard second-line chemotherapy regimen used to treat patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has been docetaxel [1]. In 2015, two international open-label, randomized phase III studies, CheckMate-017 [2] and CheckMate-057 [3], compared nivolumab, a fully humanized immunoglobulin G4 programmed death 1 (PD-1) immune checkpoint inhibitor antibody, with docetaxel in patients with advanced NSCLC that had progressed during or after platinum-based chemotherapy. Both trials found that overall survival (OS) was significantly better with nivolumab than with docetaxel. Also in 2015, two phase II studies [4]—ONO-4538-05 and ONO-4538-06—conducted in patients with squamous and non-squamous advanced NSCLC in Japan found that the objective response rates (ORRs) to nivolumab were consistent with the efficacy achieved in CheckMate-017 and CheckMate-057. Based on these results, nivolumab was approved in Japan on 17 December 2015 for patients with previously treated advanced NSCLC.

The high cost of drugs used to treat advanced cancer, including nivolumab, are the most controversial aspects of this treatment. The rates of progressive disease (PD) according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) 1.1 criteria [5] have been reported to be higher in patients treated with nivolumab than with docetaxel [2–4]. To prevent wastage of medical resources, a predictive biomarker for effective response to nivolumab would be helpful. The predictive value of PD ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression [3, 6, 7], the density of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes [8], mutation burden [9, 10], and clonal neoantigens [11] have been evaluated. However, limited data are available on these candidate biomarkers in clinical practice in Japan. Therefore, the objective of this study was to investigate markers predictive of the clinical response to nivolumab monotherapy in patients with advanced NSCLC.

Patients and methods

The medical records of patients with advanced NSCLC treated with nivolumab monotherapy (3 mg/kg, every 2 weeks) at Shizuoka Cancer Center between December 2015 and April 2016 were retrospectively reviewed. Chemoradiotherapy or molecular targeted therapy was counted as a single regimen. Maintenance therapy that continued the administration of the initial chemotherapy regimen was considered to be first-line chemotherapy. Maintenance therapy that included a switch to the administration of a new chemotherapy agent that was not part of the original chemotherapy regimen was not considered to be first-line chemotherapy. Chemotherapy for recurrence within 6 months of the patient completing adjuvant chemotherapy or re-administration after the failure of a regimen was counted as the patient undergoing one chemotherapy regimen for advanced disease.

Treatment immediately before nivolumab monotherapy was recorded as either chemotherapy, curative-intent chemoradiotherapy, or palliative radiotherapy, wherein palliative radiotherapy included stereotactic radiosurgery, stereotactic radiotherapy, and whole-brain radiation therapy. For “response to the treatment immediately before nivolumab monotherapy,” the effect of radiotherapy was included together with that of chemotherapy if the chemotherapy had been initiated within 1 week of the last administration of radiotherapy.

The objective tumor response of nivolumab was determined following the RECIST version 1.1 guidelines [5]. The efficacy of the previous treatment of nivolumab was divided into two groups: responders and non-responders. In patients treated with chemotherapy or curative-intent chemoradiotherapy, responders were those patients achieved complete response (CR) or partial response (PR) according to the RECIST version 1.1 guidelines. A scan to confirm the response was not required in the present study. In patients treated only with palliative radiotherapy, responders were patients who achieved a >30% reduction in the diameter of target lesions with a pretreatment diameter of ≥10 mm. For our study, we selected up to two target lesions. The objective tumor response was confirmed using computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) within 2 months of the last administration of radiotherapy.

Univariate and multivariate analyses were conducted to identify the relationships between the response to nivolumab monotherapy and the clinical characteristics of patients with NSCLC. Categorical variables were tested for significance using the Fisher’s exact test or the Chi-squared test, as appropriate. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to assess the relationship between patient variables and the response to nivolumab monotherapy. Progression-free survival (PFS) was estimated using Kaplan–Meier curves with two-sided log-rank test. The cutoff date for the survival analysis was 15 November 2016. All p values were two-sided, and values of <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP software version 11.2.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Shizuoka Cancer Center (IRB No. 28-J48-28-1-2).

Results

Patient characteristics

Fifty patients with advanced NSCLC were treated with nivolumab monotherapy during the study interval (Table 1). The median patient age was 65 (range 39–76) years, 30 (60%) were men, 45 (90%) had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (PS) of 0 or 1, and 31 patients (62%) had a history of smoking. According to the seventh edition of the TNM lung cancer staging criteria, ten patients (20%) had stage III NSCLC (stage IIIA, n = 3; stage IIIB, n = 7), 29 patients (58%) had stage IV disease, and 11 patients (22%) had recurrent disease after surgical resection at the time of first-line chemotherapy. Based on histological criteria, six patients (12%) were diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma, and 44 patients (88%) with non-squamous NSCLC. Of the patients with non-squamous NSCLC, 16 patients (36%) were diagnosed with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-mutant NSCLC. Regarding the number of prior chemotherapy regimens before nivolumab monotherapy, ten patients (20%) had undergone one prior chemotherapy regimen, nine patients (18%) had undergone two, 14 patients (28%) had undergone three, and 17 patients (34%) had undergone four or more. Sixteen patients (32%) were administered palliative radiotherapy immediately before undergoing nivolumab monotherapy, including seven patients who underwent stereotactic radiosurgery due to brain metastasis (n = 7), seven patients who underwent stereotactic radiotherapy due to brain metastasis (n = 1), bone metastasis (n = 4), lymph node metastasis (n = 1), or adrenal gland metastasis (n = 1), and two patients who underwent whole-brain radiotherapy due to brain metastasis (n = 1) or due to carcinomatous meningitis and brain metastasis (n = 1). Among these 16 patients, the effect of palliative radiation was assessed in seven patients with CT or MRI before nivolumab administration and in six patients with CT or MRI within 1 month after nivolumab administration. Also, two patients (4%) were administered curative-intent concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Thirty-two patients (64%) underwent chemotherapy immediately before the initiation of nivolumab monotherapy. Fifteen patients (30%) were responders to the treatment immediately before nivolumab monotherapy and 35 patients (70%) were non-responders to the treatment immediately before nivolumab monotherapy. The median interval between the last administration of chemotherapy or radiotherapy and the initiation of nivolumab monotherapy was 1.3 (range 0.03–16.2) months. Patients were stratified according to the interval between the last day of the previous therapy and the initiation day of nivolumab monotherapy into two categories: 0–3 months (n = 39, 78%) and >3 months (n = 11, 22%). Only three (6%) patients were treated with EGFR–tyrosine kinase inhibitors immediately before nivolumab monotherapy.

Treatment efficacy

The median number of cycles of nivolumab monotherapy that were administered was four (range 1–20). Of the 50 patients nine achieved a PR, 12 achieved stable disease (SD) status, and 29 developed PD according to the RECIST criteria. None of the patients achieved a CR. The ORR was 18% [95% confidence interval (CI) 10–31].

The results of univariate and multivariate analysis of factors predictive of response to nivolumab monotherapy are shown in Table 2. In the univariate analysis, the patients with squamous cell carcinoma had a significantly better response rate than those with non-squamous cell carcinoma (ORR 67 vs. 11%, respectively; p = 0.0068). Also, patients receiving nivolumab as second- or third-line therapy tended to have better response rates than that those receiving nivolumab as fourth-line or later therapy (ORR 32 vs. 10%, respectively; p = 0.0670). Responders to the treatment immediately before nivolumab monotherapy had a significantly better response rate to nivolumab monotherapy than non-responders (ORR 47 vs. 3%, respectively; p < 0.0001). A waterfall plot of each patient’s best response to nivolumab treatment, classified as best overall response to chemotherapy or curative-intent chemoradiotherapy prior to nivolumab administration, is shown Fig. 1a. In addition, a waterfall plot of each patient’s best response to nivolumab treatment, classified as responder or non-responder to palliative radiotherapy prior to nivolumab administration, is shown in Fig. 1b. Nivolumab monotherapy was more effective in patients who had achieved a response to the previous treatment. In other words, among the non-responders, only two patients exhibited marginal tumor shrinkage. On the other hand, in this study response to the treatment administered before the final pre-nivolumab treatment was not associated with response to nivolumab monotherapy (p = 0.2501). Multivariate logistic regression found that “histology” [squamous: odds ratio (OR) 0.00054; 95% CI 0–0.27; p = 0.0040] and “response to the treatment immediately before nivolumab monotherapy” (OR 0.0011; 95% CI 0–0.092; p < 0.0001) were independent predictors of response to nivolumab monotherapy. Subgroup analyses of “response to the treatment immediately before nivolumab monotherapy” revealed that responders to palliative radiotherapy immediately before nivolumab monotherapy had significantly better responses to nivolumab monotherapy than non-responders (ORR 67 vs. 0%, respectively; p = 0.0082). Responders to chemotherapy or curative-intent chemoradiotherapy immediately before nivolumab monotherapy had better responses to nivolumab monotherapy than non-responder to previous chemotherapy or curative-intent chemoradiotherapy (ORR 44 vs. 4%, respectively, OR 0.05; 95% CI 0.0048–0.57; p = 0.0118).

a A waterfall plot, classified as best overall response to chemotherapy or curative-intent chemoradiotherapy prior to nivolumab administration, showing the percentage change from baseline in the sum of the diameters of tumor lesions in 32 patients who received nivolumab. b A waterfall plot, classified as responder or non-responder to palliative radiotherapy prior to nivolumab, showing the percentage change from baseline in the sum of the diameters of tumor lesions in 14 patients who received nivolumab. CR Complete response, PR partial response, SD stable disease, PD progressive disease, RECIST Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors

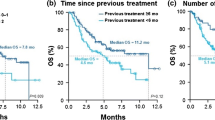

The median PFS at the time of nivolumab monotherapy was 2.1 months (Fig. 2a). On univariate analyses, responders to the treatment immediately before nivolumab monotherapy tended to have longer PFS than non-responders (median PFS 5.3 vs. 1.8 months, respectively; p = 0.09; Fig. 2b).

a Progression-free survival (PFS) curve at the time of nivolumab for 50 patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). b PFS curve at the time of initiation of nivolumab for 15 responders to the treatment immediately before nivolumab monotherapy with NSCLC and for 35 non-responders to the treatment immediately before nivolumab monotherapy with NSCLC. HR Hazard ratio, CI confidence interval

Discussion

The results of this retrospective analysis demonstrate that patients who responded to the treatment immediately before nivolumab monotherapy and those with squamous cell carcinoma nivolumab monotherapy had good response rates to nivolumab monotherapy. Markers predictive of effective response to nivolumab monotherapy have been previously proposed. In one study, PD-L1 expression on tumor cells was found to be a predictive biomarker of nivolumab monotherapy in previously treated patients with advanced NSCLC, melanoma, or renal cell cancer [6]. In the CheckMate-057 trial [3], PD-L1 expression was significantly associated with improved OS, and in the KEYNOTE-010 trial [7], treatment with pembrolizumab, a highly selective IgG4-κ humanized monoclonal antibody directed against the human cell surface receptor PD-1, significantly prolonged OS compared with treatment with docetaxel in patients with previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced NSCLC. Also, in the KEYNOTE-024 trial, pembrolizumab was significantly associated with longer OS than platinum-based combination chemotherapy in patients with previously untreated advanced NSCLC and a PD-L1 tumor proportion score of ≥50% [12]. However, PD-L1 expression did not predict improved OS of patients treated with nivolumab monotherapy in either the CheckMate-017 trial or OAK trial [2, 13]. Therefore, PD-L1 expression alone may be not be able to predict response to nivolumab monotherapy. In addition, little is known of other factors predictive of response to nivolumab monotherapy in patients with NSCLC in the clinical setting. In our study, therapeutic effectiveness immediately before the administration of nivolumab monotherapy was shown to be a predictive marker of response to nivolumab monotherapy.

Our results in this series of patients with NSCLC showed that the response of patients to the most recent treatment (chemotherapy or curative-intent chemoradiotherapy) before the initiation of nivolumab monotherapy had an impact on ORR. This effect may be due to either the immunogenic tumor cell death or the abscopal effect. Immunogenic tumor cell death caused by chemotherapy can stimulate anticancer immune effectors [14–16]. The abscopal effect refers to tumor regression at a site distant from the primary tumor because of radiotherapy [17] and is thought to depend on activation of the immune system [18–22]. Preclinical studies have found that radiation combined with immunotherapy may have a synergistic effect, significantly increasing CD4+ and CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in secondary tumors outside the field of radiotherapy [23]. Therefore, the immune response to agents, such as nivolumab and pembrolizumab, may be amplified by immunogenic tumor cell death or the abscopal effect.

The ORR of patients with non-squamous cell carcinoma in this series was lower than in that in the CheckMate-057 trial [3]. Possible explanations for this difference may be the proportion of patients in the two trials with a smoking history and with NSCLC harboring an EGFR mutation. Relatively more never-smokers and patients with EGFR mutation were included in our study than in CheckMate-057. The mutation burden associated with smoking [24] or deficient DNA mismatch repair [25, 26] may be predictive of response to anti-PD-1 therapy in lung cancer and colorectal cancer [9, 10]. Although the efficacy of nivolumab therapy for patients with driver mutations is controversial [27], a subanalysis of a recent prospective trial found that patients with NSCLC with EGFR mutations had a lower ORR rate [28]. Also, a recent retrospective study showed that patients who never smoked and had NSCLC tumors carrying EGFR mutations had a low response rate to PD-1 pathway blockade [29].

This study has several limitations. Firstly, PD-L1 expression was not routinely assayed because no diagnostic kits are commercially available in Japan. However, CheckMate-017 and CheckMate-057 met their primary endpoint regardless of PD-L1 expression. Therefore, the potential impact of PD-L1 on the response to nivolumab monotherapy was expected to be minimal. Secondly, this was a retrospective, non-randomized study performed at a single center.

However, the results presented here must be considered as a first report on the potential of the response to the most recent treatment before nivolumab monotherapy to be predictive of a response to nivolumab monotherapy. We suggest that “response to the treatment immediately before nivolumab monotherapy” may be a useful predictor of clinical response to nivolumab by patients with NSCLC in clinical practice. Also, patients categorized as never smoked, EGFR mutant, poor PS, and non-response to treatment before nivolumab would be unlikely to derive a benefit from nivolumab monotherapy and should not be administered nivolumab as an earlier line chemotherapy for NSCLC because the high cost of nivolumab is an issue. A larger study is needed to confirm this finding.

References

Shepherd FA, Dancey J, Ramlau R et al (2000) Prospective randomized trial of docetaxel versus best supportive care in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 18:2095–2103

Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P et al (2015) Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 373:123–135. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1504627

Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L et al (2015) Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 373:1627–1639. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1507643

Makoto N, Toyoaki H, Kazuhiko N et al (2015) Phase II studies of nivolumab (anti-PD-1, BMS-936558, ONO-4538) in patients with advanced squamous (sq) or nonsquamous (non-sq) non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). J Clin Oncol 33(suppl):abstr8027

Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J et al (2009) New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 45:228–247. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026

Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR et al (2012) Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med 366:2443–2454. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1200690

Herbst RS, Baas P, Kim DW et al (2016) Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 387:1540–1550. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01281-7

Tumeh PC, Harview CL, Yearley JH et al (2014) PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature 515:568–571. doi:10.1038/nature13954

Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A et al (2015) Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science 348:124–128. doi:10.1126/science.aaa1348

Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H et al (2015) PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N Engl J Med 372:2509–2520. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1500596

McGranahan N, Furness AJ, Rosenthal R et al (2016) Clonal neoantigens elicit T cell immunoreactivity and sensitivity to immune checkpoint blockade. Science 351:1463–1469. doi:10.1126/science.aaf1490

Reck M, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG et al (2016) Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 375:1823–1833. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1606774

Barlesi F, Park K, Ciardiello F et al (2016) Primary analysis from OAK, a randomized phase III study comparing atezolizumab with docetaxel in 2L/3L NSCLC. Ann Oncol 27[Suppl 6]:vi552–vi587

Obeid M, Panaretakis T, Tesniere A et al (2007) Leveraging the immune system during chemotherapy: moving calreticulin to the cell surface converts apoptotic death from “silent” to immunogenic. Cancer Res 67:7941–7944. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1622

Apetoh L, Ghiringhelli F, Tesniere A et al (2007) Toll-like receptor 4-dependent contribution of the immune system to anticancer chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Nat Med 13:1050–1059. doi:10.1038/nm1622

Zitvogel L, Kepp O, Kroemer G (2011) Immune parameters affecting the efficacy of chemotherapeutic regimens. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 8:151–160. doi:10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.223

Mole RH (1953) Whole body irradiation; radiobiology or medicine? Br J Radiol 26:234–241. doi:10.1259/0007-1285-26-305-234

Lee Y, Auh SL, Wang Y et al (2009) Therapeutic effects of ablative radiation on local tumor require CD8 + T cells: changing strategies for cancer treatment. Blood 114:589–595. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-02-206870

Lugade AA, Moran JP, Gerber SA et al (2005) Local radiation therapy of B16 melanoma tumors increases the generation of tumor antigen-specific effector cells that traffic to the tumor. J Immunol 174:7516–7523

Nesslinger NJ, Sahota RA, Stone B et al (2007) Standard treatments induce antigen-specific immune responses in prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res 13:1493–1502. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1772

Schaue D, Comin-Anduix B, Ribas A et al (2008) T-cell responses to survivin in cancer patients undergoing radiation therapy. Clin Cancer Res 14:4883–4890. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4462

Schaue D, Ratikan JA, Iwamoto KS et al (2012) Maximizing tumor immunity with fractionated radiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 83:1306–1310. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.09.049

Dewan MZ, Galloway AE, Kawashima N et al (2009) Fractionated but not single-dose radiotherapy induces an immune-mediated abscopal effect when combined with anti-CTLA-4 antibody. Clin Cancer Res 15:5379–5388. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0265

Lee W, Jiang Z, Liu J et al (2010) The mutation spectrum revealed by paired genome sequences from a lung cancer patient. Nature 465:473–477. doi:10.1038/nature09004

Timmermann B, Kerick M, Roehr C et al (2010) Somatic mutation profiles of MSI and MSS colorectal cancer identified by whole exome next generation sequencing and bioinformatics analysis. PLoS One 5:e15661. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0015661

Cancer Genome Atlas N (2012) Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature 487:330–337. doi:10.1038/nature11252

Larkin J, Lao CD, Urba WJ et al (2015) Efficacy and safety of nivolumab in patients with BRAF V600 mutant and BRAF wild-type advanced melanoma: a pooled analysis of 4 clinical trials. JAMA Oncol 1:433–440. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.1184

Gettinger S, Rizvi NA, Chow LQ et al (2016) Nivolumab monotherapy for first-line treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol 34:2980–2987. doi:10.1200/JCO.2016.66.9929

Gainor JF, Shaw AT, Sequist LV et al (2016) EGFR mutations and ALK rearrangements are associated with low response rates to PD-1 pathway blockade in non-small cell lung cancer: a retrospective analysis. Clin Cancer Res 22:4585–4593. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-3101

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr. Kobayashi is the guarantor of the article. Dr. Kobayashi contributed to conceiving the study design, performing the data analysis, and producing the initial draft of the manuscript; participated in data generation, interpretation of the analysis, final preparation of the manuscript; read and approved the final manuscript. Dr. Omori contributed to interpretation of the analysis and final preparation of the manuscript; read and approved the final manuscript. Dr. Nakashima contributed to interpretation of the analysis and final preparation of the manuscript; read and approved the final manuscript. Dr. Wakuda contributed to interpretation of the analysis and final preparation of the manuscript; read and approved the final manuscript. Dr. Ono contributed to interpretation of the analysis and final preparation of the manuscript; read and approved the final manuscript. Dr. Kenmotsu contributed to interpretation of the analysis and final preparation of the manuscript; read and approved the final manuscript. Dr. Naito contributed to interpretation of the analysis and final preparation of the manuscript; read and approved the final manuscript. Dr. Murakami contributed to interpretation of the analysis and final preparation of the manuscript; read and approved the final manuscript. Dr. Endo contributed to interpretation of the analysis and final preparation of the manuscript; read and approved the final manuscript. Dr. Takahashi contributed to conceiving the study design and producing the initial draft of the manuscript; participated in interpretation of the analysis, final preparation of the manuscript; read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

HK reports honoraria from Eli Lilly and Taiho Pharmaceutical. SO reports honoraria from Chugai Pharmaceutical, Ono Pharmaceutical, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Taiho Pharmaceutical. KN reports honoraria from Eli Lilly, Ono Pharmaceutical, Mochida Pharmaceutical, and Taiho Pharmaceutical. KW reports honoraria from Taiho Pharmaceutical, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Ono Pharmaceutical. AO reports honoraria from Taiho Pharmaceutical, Chugai Pharmaceutical, and Takeda Pharmaceutical. HK reports honoraria from Ono Pharmaceutical, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Bristol-Myers, Taiho Pharmaceutical, and Kyowa Hakko Kirin, and research funding from AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim. TN reports honoraria from Ono Pharmaceutical. HM reports honoraria from Chugai Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Taiho Pharmaceutical, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Ono Pharmaceutical, Bristol-Myers, and Astellas. EM reports honoraria from Ono Pharmaceutical. TT reports honoraria from Ono Pharmaceutical, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, Eli Lilly, and Chugai Pharmaceutical, and research funding from Ono Pharmaceutical, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Taiho Pharmaceutical, and MSD.

About this article

Cite this article

Kobayashi, H., Omori, S., Nakashima, K. et al. Response to the treatment immediately before nivolumab monotherapy may predict clinical response to nivolumab in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Clin Oncol 22, 690–697 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-017-1118-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-017-1118-x