Abstract

The predictive values of current risk stratification scales such as the Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysm Treatment Score (UIATS) and the PHASES score are debatable. We evaluated these scores using a cohort of ruptured intracranial aneurysms to simulate their management recommendations had the exact same patients presented prior to rupture. A prospectively maintained database of ruptured saccular aneurysm patients presenting to our institution was used. The PHASES score was calculated for 992 consecutive patients presenting between January 2002 and December 2018, and the UIATS was calculated for 266 consecutive patients presenting between January 2013 and December 2018. A shorter period was selected for the UIATS cohort given the larger number of variables required for calculation. Clinical outcomes were compared between UIATS-recommended “observation” aneurysms and all other aneurysms. Out of 992 ruptured aneurysms, 54% had a low PHASES score (≤5). Out of the 266 ruptured aneurysms, UIATS recommendations were as follows: 68 (26%) “observation,” 97 (36%) “treatment,” and 101 (38%) “non-definitive.” The UIATS conservative group of patients developed more SAH-related complications (78% vs. 65%, p=0.043), had a higher rate of non-home discharge (74% vs. 46%, p<0.001), and had a greater incidence of poor functional status (modified Rankin scale >2) after 12–18 months (68% vs. 51%, p=0.014). Current predictive scoring systems for unruptured aneurysms may underestimate future rupture risk and lead to more conservative management strategies in some patients. Patients that would have been recommended for conservative therapy were more likely to have a worse outcome after rupture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Unruptured intracranial aneurysms (UIAs) are found in up to 3–5% of the population with greater prevalence among females [1, 2]. With the growing use of advanced imaging technology for diagnostic purposes, the detection rate of UIAs has been rising [3]. Cerebrovascular specialists are facing increased difficulty with management decisions, given the high morbidity and mortality rates of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) [4], the risks of treatment, and conflicting data on natural history [5]. In addition, non-specialists are increasingly unclear about current recommendations. Guidelines focusing on UIAs exist [6], but uncertainties and wide variations in management practices persist [7, 8].

In an effort to optimize decision-making in UIAs, risk stratification tools and management algorithms such as the Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysm Treatment Score (UIATS) [9] and the Population, Hypertension, Age, Size, Earlier subarachnoid hemorrhage, Site (PHASES) [10] score have been developed. The UIATS was developed using a Delphi consensus approach involving an international multidisciplinary panel of 69 cerebrovascular specialists and recommends a management decision (repair, conservative management, or non-definitive) based on 29 factors that estimate the risks of both hemorrhage and treatment. The PHASES score was created based on a pooled statistical analysis of six cohort studies and aims to predict the 5-year risk of aneurysm rupture based on six factors without offering a management recommendation. Although these scores are being used in clinical practice, validation efforts and effects on patient safety and long-term outcome are far from complete. While based on several individual patient and aneurysm characteristics, real-world applicability to clinical practice remains questionable, especially given our limited knowledge of aneurysm rupture and natural history. As these scores capture the current consensus on our understanding of UIAs and how they should be managed, it is important to test their performance rigorously.

We aimed to evaluate these scores in a cohort of exclusively ruptured intracranial aneurysms using a large, prospectively maintained database to simulate the management decisions that would have been recommended had the aneurysms been detected before rupture. Outcomes of these decisions were also assessed. We further performed a sensitivity analysis by modeling various assumptions that would drive recommendations towards or against treatment and compared these results. Any change in aneurysm size following rupture would complicate this analysis particularly if aneurysms shrink following rupture; however, pre- and post-rupture measurements on the same aneurysm have indicated the absence of shrinkage [11] or even possible enlargement in maximal diameter [12]. Studying natural history by following up unruptured aneurysms over a long period of time can be impractical, resource-intensive, and biased, given the lack of clinical equipoise and the necessity of treating unruptured aneurysms that are high-risk. This simulation-based approach provides a more feasible alternative.

Materials and methods

Patients

An IRB-approved, prospectively maintained database of consecutive patients presenting with ruptured intracranial aneurysms to Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions was retrospectively reviewed for this study. Patients presenting from January 1, 2002, to December 31, 2018, were included in the PHASES score analysis. Given that the UIATS constitutes a more complex scoring system with a larger number of demographic and radiological variables, a list of patients presenting over a smaller, 5-year period from January 1, 2013, to December 31, 2018, during which more detailed patient electronic records were available, was retrospectively reviewed. Patients with missing data that precluded accurate UIATS scoring were excluded. The exclusion criteria included fusiform, mycotic, dissecting, arteriovenous malformation-related, and previously treated aneurysms, as well as patients younger than 16 years of age.

PHASES and UIATS score variables

The PHASES [10] and UIATS [9] score variables were extracted at the time of presentation with aneurysmal SAH and were defined according to the criteria outlined in the original studies. Reports from the patient history of diplopia or other neurologic disturbances suggestive of cranial nerve palsy in the period prior to rupture were also noted. Additionally, the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) [13] was derived for patients in order to estimate life expectancy as has been described previously [14]. Digital subtraction angiography was used when available (n=261, 98%). CT angiography was used for the remaining patients. Imaging studies were reviewed in order to extract aneurysm-specific characteristics such as maximum diameter, parent artery diameter, neck width, and height. These measurements were used to calculate size and aspect ratios. CT angiography and data from other imaging studies were used to determine whether there was a significant mass effect from the aneurysm. An aneurysm was labeled as complex if it had any one of the following features: marked lobulations, neck wider than the parent artery, calcification, intra-aneurysm thrombus, branch artery incorporated into the neck or sac, very small diameter (<3 mm), or tortuosity/stenosis in the proximal vessel. These imaging characteristics were noted by trained neuroradiologists.

Hemorrhage severity and outcome

The Fisher grade, Hunt-Hess score, and World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies (WFNS) score were determined on presentation, and aneurysm treatment was recorded. Clinical outcomes included the occurrence of any SAH-related complication such as clinically significant vasospasm, hydrocephalus, seizure, syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH), hematoma formation, ischemic stroke, and third cranial nerve palsy. Clinically significant vasospasm was defined as angiographic vasospasm along with corresponding symptoms or severe vasospasm requiring intra-arterial vasodilator therapy. Other clinical outcomes included length of stay, discharge disposition, and functional status at 12–18 months post-discharge as measured by the modified Rankin scale (mRS).

Statistical analysis

The SPSS software (version 25.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used for data analysis with statistical significance set at p<0.05. The 6 PHASES and 29 UIATS score variables were utilized to calculate the respective score values. The percentage of ruptured aneurysms with a low PHASES score (≤5) [15, 16], reflecting a 5-year risk of rupture less than or equal to 1.3%, was calculated. Subsequently, the UIATS management recommendation was derived according to the methodology described by Etminan et al. in the original paper [9]. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient and aneurysm characteristics at the time of presentation, and these were broken down by UIATS management recommendation: “observation,” “treatment,” or “non-definitive.” Clinical and radiological severities of subarachnoid hemorrhage were compared between the UIATS-recommended “observation” aneurysms and all the other aneurysms. Outcome comparisons included treatment-related complications, SAH-related complications, length of stay, non-home discharge, and poor functional status (mRS>2). The chi-squared test and independent samples t test were used for these comparisons.

Sensitivity analysis

Given that a simulation of UIAs is being created from a series of ruptured aneurysms, there are two potential biases that can be accounted for. First, there were four variables from the UIATS that were more applicable to the scenario of UIAs: thromboembolic events from aneurysm, reduced quality of life from fear of aneurysm rupture, aneurysm growth on serial imaging, and de novo aneurysm formation. Since none of these characteristics can be realistically evaluated in patients presenting with ruptured aneurysms, a study on UIAs and the UIATS by Ravindra et al. [14] was used to extract the percentage of affected patients for every one of these variables for imputation purposes. This study was selected since it similarly evaluated the UIATS with identical definitions and because it took place at a tertiary academic referral center such as ours. Patients from our study sample were then randomly selected according to these percentages and were assigned a positive value for every variable of interest. Since all these characteristics favor aneurysm repair, the newly derived UIATS recommendations on that basis would be skewed more towards treatment. Second, aneurysm morphology may change after rupture. Namely, irregularities and lobulation (blebs or daughter sacs), which are characteristics that would favor treatment in UIAs, are more commonly found in ruptured aneurysms [12]. To account for that, extrapolation of the percentage of irregular/lobulated aneurysms from the UIA series of Ravindra et al. [14] was performed to obtain a more realistic incidence of irregular aneurysms and therefore UIATS recommendations that are more skewed towards conservative therapy.

Results

Presentation characteristics

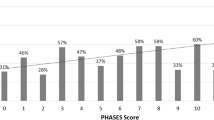

A total of 1000 patients presented with ruptured aneurysms during the period extending from January 1, 2002, to December 31, 2018, and the PHASES score variables were available for 992 (99%) of these aneurysms (Table 1). Most of these aneurysms (538/992, 54%) had a low PHASES (≤5) score (Fig. 1).

UIATS scores were calculated on a total of 273 patients presenting with a ruptured aneurysm during the 5-year period from January 1, 2013, to December 31, 2018. Because of incomplete data available in the medical record and thus inability to calculate the UIATS, 7 (2.6%) patients were excluded. UIATS scores were calculated for aneurysms as if they were unruptured, and recommendations were as follows: 68 (26%) labeled for observation, 97 (36%) labeled for treatment, and 101 (38%) labeled as non-definitive. Demographically, the mean age was 56 years (SD=15), and most patients were female (199/266, 75%). The racial composition of the cohort was 116 (44%) White, 107 (40%) Black, 13 (5%) Asian, 20 (7%) Hispanic, and 10 (4%) of other races. None of the patients was of Japanese, Finnish, or Inuit ethnicity. Most aneurysms were located in the anterior communicating artery (ACoA) or posterior communicating artery (PCoA) regions (151/266, 57%), and the mean aneurysm size was 6.5 mm (SD=3.5). The majority of aneurysms were treated (254/266, 96%) either with endovascular therapy (136/254, 53%) or open surgery (118/254, 47%). Presentation characteristics are summarized in Table 2.

After extrapolating for variables that would skew scores towards treatment (aneurysm thromboembolic events (n=60 patients), poor quality of life from fear of rupture (n=14 patients), aneurysm growth on serial imaging (n=11 patients), and de novo aneurysm formation on serial imaging (n=12 patients)), UIATS management recommendations were as follows: 60 (23%) labeled for observation, 123 (46%) labeled for treatment, and 83 (31%) labeled as non-definitive. Following extrapolation of aneurysms with irregular/lobulated morphology (n=60 patients) from an unruptured series (a process that would skew results towards conservative management), UIATS management recommendations were as follows: 90 (34%) labeled for observation, 77 (29%) labeled for treatment, and 99 (37%) labeled as non-definitive. Figure 2 summarizes the UIATS management recommendations in the three previously mentioned scenarios. The mean PHASES score increased successively while moving from the UIATS observation group to the non-definitive group followed by the treatment group of ruptured aneurysms (4.2±2.2 vs. 5.7±2.7 vs. 6.2±2.3, respectively, ANOVA p<0.001).

Outcomes

Outcome comparisons are summarized in Table 3. The Hunt-Hess (p=0.029) and WFNS (p=0.040) scores were significantly higher in the UIATS-recommended “observation” group of patients. The UIATS-recommended “observation” group of aneurysms was less likely to be treated (88% vs. 98%, p=0.003) and more likely to undergo endovascular therapy vs. open surgery when treated (p=0.082). SAH-related complications occurred in 181 (68%) patients (Fig. 3) and were significantly more common among the UIATS-recommended “observation” group (78% vs. 65%, p=0.043). Treatment-related medical or surgical complications occurred in 79 (29%) patients (Fig. 4), with no significant difference between both UIATS groups (p=0.166). The mean length of stay was 21 days (SD=14) with no significant difference between both groups (p=0.945). The UIATS-recommended “observation” group had significantly higher rates of non-home discharge (74% vs. 46%, p<0.001) and poor functional status (68% vs. 51%, p=0.014, Fig. 5) at 12–18 months. Similar results were obtained once the UIATS non-definitive aneurysms were grouped with the UIATS observation aneurysms (combined n=169) and compared to UIATS treatment (n=97) aneurysms (non-home discharge 60% vs. 39%, p=0.001; poor functional status 63% vs. 41%, p=0.001). Analyzing the observation, non-definitive, and treatment aneurysms separately, the non-home discharge and poor functional status rates were highest in the observation aneurysms (non-home discharge 74% vs. 52% vs. 39%, respectively, p<0.001; poor functional status 68% vs. 59% vs. 41%, respectively, p=0.002).

Discussion

There are several scoring systems for unruptured intracranial aneurysms that seek to predict future rupture risk. Given the low annual rupture rate of aneurysms, these are difficult to evaluate prospectively and may underestimate the true risk of rupture and therefore overly recommend conservative management. In this study, two current scores for unruptured intracranial aneurysms were evaluated using a cohort of ruptured intracranial aneurysms to simulate the management recommendations that would have been calculated if the same patients had presented prior to rupture. Using these scoring systems, 23–34% of these now known ruptured aneurysms would have been recommended for observation, had they been detected before rupture, and had the UIATS recommendations been followed. Another 31–37% would have been given equivocal recommendations with only 29–46% of these aneurysms recommended for definitive treatment to prevent rupture. In a larger cohort of around 1000 ruptured aneurysms, more than half (54%) were classified as having a low risk of rupture (5-year risk ≤1.3%). Furthermore, the presentation severity, incidence of SAH-related complications, rate of non-home discharge, and long-term functional status were all worse after rupture in the cohort of aneurysms for which observation would have been recommended. Although the purpose of these scores is not to predict the outcome, patients with aneurysms misclassified as “low-risk” may experience relatively poorer outcomes, emphasizing the clinical significance of our findings.

Effect of rupture on aneurysm size

To carry out these comparisons, we relied on recent multi-center studies that demonstrate that aneurysms do not undergo a significant change in their size at the time of rupture. Namely, Rahman et al. performed pre- and post-rupture measurements on the same aneurysm in 13 patients and concluded the absence of shrinkage following subarachnoid hemorrhage [11]. Moreover, Skovdin et al. conducted a similar comparative analysis in 29 patients and indicated that aneurysms may even increase in size following rupture (median maximal diameter increase by 2.1 mm, p<0.001) [12]. As an increase in size would generally lead to a higher-risk PHASES classification, the number of ruptured aneurysms misclassified as low-risk by PHASES may be higher than reported in this study.

UIATS correlation with management decisions

Real-world adherence to UIATS recommendations and actual management decisions have been previously evaluated in UIAs. An analysis by Smedley et al. of 296 patients with UIAs reported an over-treatment rate of 15.6% when actual management strategies were compared to UIATS recommendations [17]. Discrepancies between real-world decisions and UIATS recommendations have also been identified by Ravindra et al. who identified a limited predictive accuracy (area under the curve=0.646) when comparing UIATS results to actual treatment practices [14]. Namely, among the aneurysms labeled as “conservative” by the UIATS, 20% underwent intervention. Hernandez-Duran et al. reported a low correlation coefficient between UIATS recommendations and real-world practice, whereby 67% of aneurysms labeled for “conservative” management by UIATS were actually treated [18]. More recently, our team similarly indicated that 22% of UIATS-recommended “conservative” UIAs seen at our institution were discordantly treated [19]. Our results herein may help contextualize these rates of “over-treatment” encountered in the literature. Specifically, there might be many other variables that emerge in the physician-patient interaction and that are not adequately weighted or captured by the UIATS; these factors might be encouraging cerebrovascular specialists to treat unruptured intracranial aneurysms more frequently than the UIATS would recommend. This could possibly translate into better long-term patient outcomes given the underestimation of rupture by UIATS shown in our results. Moreover, the missed opportunity to treat these UIATS-recommended “conservative” aneurysms seems to be more detrimental when outcomes are compared to other aneurysms, most likely due to the increased age and comorbidity burden of these patients. For example, the UIATS gives significant weight to increasing patient age as a factor in conservative management recommendations. The mean age of the UIATS “conservative” cohort in our study was 68.5 years. However, effective treatment of aneurysms with low morbidity and mortality rates can still be achieved in elderly patients with reasonable life expectancy, especially when endovascular therapy is utilized [20,21,22,23,24].

UIATS correlation with aneurysm rupture

Validations of the UIATS have been previously performed in smaller cohorts with ruptured aneurysms including 146 patients in Italy and 212 patients in Germany [25, 26]. However, both studies neglected to account for variables that could only be assessed in unruptured aneurysms and for the higher prevalence of irregular morphology in ruptured aneurysms. As a result, the reported percentage of ruptured aneurysms that would have been offered a conservative recommendation was 32% in both cohorts, which lies at the higher end of the spectrum reported in our sensitivity analysis (23–34%). Our findings in a North American cohort of 273 patients suggest that false-negative rates for the UIATS may be lower than previously reported.

Despite selection bias, the UIATS has been evaluated in patients with unruptured aneurysms recommended for conservative management and followed up over time. In Juvela et al.’s analysis of 142 patients, the UIATS had a 100% sensitivity in recommending treatment for aneurysms that ruptured, yet also recommended treatment for 99% of aneurysms that did not rupture over a median follow-up of 21 years [27]. Molenberg et al. assessed the performance of the UIATS in 277 unruptured aneurysms followed up over a median of 1.3 years and revealed a sensitivity and specificity of 80% and 44%, respectively, in detecting aneurysm growth or rupture [28]. These results, taken together with our simulation, further emphasize the limitations of the UIATS.

PHASES score simulations in ruptured aneurysms

The PHASES score has been previously investigated in cohorts of ruptured aneurysms. In Hilditch et al.’s observational study of 700 ruptured aneurysms, 65% had a low PHASES score profile (≤5) and 15% were less than 3 mm in size [29]. Similar results were reported in another study on 149 ruptured aneurysms, whereby 62% of patients had a low PHASES score (≤5), and most ruptured aneurysms were less than 7 mm (62%) [15]. Pagiola et al. further corroborated these findings in 155 patients with ruptured aneurysms by noting that 71% of patients had a low PHASES score (≤5) and that 55% of aneurysms were smaller than 5 mm [16]. In another cohort of 100 ruptured aneurysms that underwent treatment, 65% also had a low PHASES score (≤5) [30]. Our PHASES score analysis in 992 ruptured aneurysms represents the largest series to date and further supports that PHASES may underpredict the true risk of aneurysm rupture. For example, as shown by Lindgren et al., aneurysm morphological characteristics such as irregularity and multi-lobular shape constitute important determinants of rupture and must weigh heavily in decision-making, even in aneurysms with low PHASES scores [31].

Ruptured aneurysms with small size

The literature also emphasizes that many of the ruptured aneurysms are in fact small. A 25-year analysis by Bender et al. revealed that 41% of ruptured aneurysms were <5 mm in size with a trend towards smaller sizes of ruptured aneurysms from 1991 to 2016 [32]. A Finnish study evaluating 2660 consecutive patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms comparably reported a trend towards a smaller maximal diameter from 1989 to 2008 [33]. The true pre-rupture size of aneurysms reported in all these ruptured aneurysm series may in fact be even smaller, as Skovdin et al. indicated that median diameter may increase by 2 mm following subarachnoid hemorrhage [12]. Whether increased treatment rates of smaller aneurysms would truly prevent future rupture is still unclear because conservative follow-up of many small aneurysms indicates negligible rupture risk [34]. A Markov decision model by Malhotra et al. failed to demonstrate the superiority of routine treatment in very tiny unruptured intracranial aneurysms (≤3 mm) and concluded that surveillance and preventive therapy should be reserved for tiny aneurysms with other elements that increase the likelihood of rupture [35]. In their review of the literature, Zanaty et al. highlight current evidence supporting the treatment of a subset of aneurysms less than 5–7 mm in view of new research findings regarding hemodynamic and inflammatory determinants of rupture [36].

Novel predictors of hemorrhage

Results of our study and other findings in the literature emphasize that our understanding of aneurysm natural history remains inadequate. Hence, long-term patient outcomes emerging from current management decisions and international consensus opinions regarding unruptured intracranial aneurysms remain unclear. Recent studies are highlighting new variables that might be more effective at determining future rupture risk. Inflammation appears to play a role in aneurysm formation, growth, and rupture [37]; accordingly, advanced imaging techniques have shown that wall enhancement is associated with elevated rupture risk [38]. Interestingly, Roa et al. demonstrated that enhancing UIA score higher on the PHASES score, likely due in part to a larger size, but do not correlate with the UIATS [39]. Greater insight into rupture risk is also being provided by dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging [40], hemodynamic parameters such as shear area [41, 42], and novel morphological characteristics such as aneurysm inflow angle [43]. Integrating these novel findings in future risk-stratification and management algorithms may improve accuracy. Ultimately, careful multidisciplinary assessment of patients with unruptured intracranial aneurysms on a case-by-case basis rather than strict adherence to published algorithms remains the optimal management approach.

Limitations

This study is a single-institution analysis conducted at a tertiary referral center with cerebrovascular expertise in North America. One of its strengths, however, is the prospective accrual of cases over this time period and confirmation of the high accuracy of this database, in particular [44]. Our findings might be generalizable only to similar institutions, but the congruence of our PHASES score analysis when compared to other smaller studies in the literature that emanate from different geographical regions does lend greater confidence in the generalizability of our results. Longer follow-up periods may also reveal whether outcome differences identified in our study persist over time. As the study attempts to estimate management decisions in UIAs from a cohort of ruptured aneurysms, biases do remain. We have conducted a sensitivity analysis in an effort to provide the range of estimates by modeling scenarios on each extreme with assumptions that would both over and under-estimate the treatment recommendations. We believe that this simulation-based approach may offer a more feasible alternative to long-term follow-up of UIAs and can still yield insightful findings regarding natural history despite obvious limitations.

Conclusion

In a simulation-based analysis, the UIATS would have recommended conservative management in a quarter to one-third of ruptured cases based on patient and aneurysm characteristics had the aneurysms been detected prior to rupture. Similarly, the PHASES score would have classified 54% of the ruptured aneurysms presenting over a 15-year period as harboring low risk for hemorrhage if detected prior to rupture. These observations underscore the limitations of strict adherence to simplified size thresholds or even comprehensive risk-stratification and management algorithms, as treatment would have been withheld for a significant number of patients who could have benefited from prophylactic interventions. Finally, patients for whom UIATS would have recommended conservative management had a worse outcome than patients who would have been assigned a treatment recommendation. Recommendations based on current scoring systems such as PHASES and UIATS may underestimate future aneurysm rupture risk, and further development of management algorithms remains warranted.

Data Availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Code availability

The code used to perform the analysis is available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Vernooij MW, Ikram MA, Tanghe HL, Vincent AJPE, Hofman A, Krestin GP, Niessen WJ, Breteler MMB, van der Lugt A (2007) Incidental findings on brain MRI in the general population. N Engl J Med 357:1821–1828. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa070972

Vlak MH, Algra A, Brandenburg R, Rinkel GJ (2011) Prevalence of unruptured intracranial aneurysms, with emphasis on sex, age, comorbidity, country, and time period: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol 10:626–636. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70109-0

Brown RDJ, Broderick JP (2014) Unruptured intracranial aneurysms: epidemiology, natural history, management options, and familial screening. Lancet Neurol 13:393–404. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70015-8

Nieuwkamp DJ, Setz LE, Algra A, Linn FHH, de Rooij NK, Rinkel GJE (2009) Changes in case fatality of aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage over time, according to age, sex, and region: a meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol 8:635–642. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70126-7

Etminan N, Rinkel GJ (2016) Unruptured intracranial aneurysms: development, rupture and preventive management. Nat Rev Neurol 12:699–713. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2016.150

Thompson BG, Brown RDJ, Amin-Hanjani S, Broderick JP, Cockroft KM, Connolly ESJ, Duckwiler GR, Harris CC, Howard VJ, Johnston SCC, Meyers PM, Molyneux A, Ogilvy CS, Ringer AJ, Torner J (2015) Guidelines for the management of patients with unruptured intracranial aneurysms: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 46:2368–2400. https://doi.org/10.1161/STR.0000000000000070

Darsaut TE, Estrade L, Jamali S, Bojanowski MW, Chagnon M, Raymond J (2014) Uncertainty and agreement in the management of unruptured intracranial aneurysms. J Neurosurg 120:618–623. https://doi.org/10.3171/2013.11.JNS131366

Etminan N, Rinkel GJE (2015) Cerebral aneurysms: cerebral aneurysm guidelines-more guidance needed. Nat Rev Neurol 11:490–491

Etminan N, Brown RD, Beseoglu K, Juvela S, Raymond J, Morita A, Torner JC, Derdeyn CP, Raabe A, Mocco J (2015) The unruptured intracranial aneurysm treatment score a multidisciplinary consensus. Neurology 85:881–889. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000001891

Greving JP, Wermer MJH, Brown RDJ, Morita A, Juvela S, Yonekura M, Ishibashi T, Torner JC, Nakayama T, Rinkel GJE, Algra A (2014) Development of the PHASES score for prediction of risk of rupture of intracranial aneurysms: a pooled analysis of six prospective cohort studies. Lancet Neurol 13:59–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70263-1

Rahman M, Ogilvy CS, Zipfel GJ, Derdeyn CP, Siddiqui AH, Bulsara KR, Kim LJ, Riina HA, Mocco J, Hoh BL (2011) Unruptured cerebral aneurysms do not shrink when they rupture: multicenter collaborative aneurysm study group. Neurosurgery 68:151–155. https://doi.org/10.1227/NEU.0b013e3181ff357c

Skodvin TO, Johnsen L-H, Gjertsen O, Isaksen JG, Sorteberg A (2017) Cerebral aneurysm morphology before and after rupture: nationwide case series of 29 aneurysms. Stroke 48:880–886. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015288

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40:373–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8

Ravindra VM, de Havenon A, Gooldy TC, Scoville J, Guan J, Couldwell WT, Taussky P, MacDonald JD, Schmidt RH, Park MS (2018) Validation of the unruptured intracranial aneurysm treatment score: comparison with real-world cerebrovascular practice. J Neurosurg 129:100–106. https://doi.org/10.3171/2017.4.JNS17548

Foreman PM, Hendrix P, Harrigan MR, Fisher WS 3rd, Vyas NA, Lipsky RH, Walters BC, Tubbs RS, Shoja MM, Griessenauer CJ (2018) PHASES score applied to a prospective cohort of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage patients. J Clin Neurosci 53:69–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2018.04.014

Pagiola I, Mihalea C, Caroff J, Ikka L, Chalumeau V, Iacobucci M, Ozanne A, Gallas S, Marques M, Nalli D, Carrete H, Caldas JG, Frudit ME, Moret J, Spelle L (2020) The PHASES score: to treat or not to treat? Retrospective evaluation of the risk of rupture of intracranial aneurysms in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neuroradiol =. J Neuroradiol 47:349–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurad.2019.06.003

Smedley A, Yusupov N, Almousa A, Solbach T, Toma AK, Grieve JP (2018) Management of incidental aneurysms: comparison of single centre multi-disciplinary team decision making with the unruptured incidental aneurysm treatment score. Br J Neurosurg 32:536–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/02688697.2018.1468019

Hernandez-Duran S, Mielke D, Rohde V, Malinova V (2018) The application of the unruptured intracranial aneurysm treatment score: a retrospective, single-center study. Neurosurg Rev 41:1021–1028. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-018-0944-2

Feghali J, Gami A, Caplan JM, Tamargo RJ, McDougall CG, Huang J (2020) Management of unruptured intracranial aneurysms: correlation of UIATS, ELAPSS, and PHASES with referral center practice. Neurosurg Rev. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-020-01356-6

Cai Y, Spelle L, Wang H, Piotin M, Mounayer C, Vanzin JR, Moret J (2005) Endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms in the elderly: single-center experience in 63 consecutive patients. Neurosurgery 57:1096–1102. https://doi.org/10.1227/01.neu.0000185583.25420.df

Gonzalez NR, Dusick JR, Duckwiler G, Tateshima S, Jahan R, Martin NA, Vinuela F (2010) Endovascular coiling of intracranial aneurysms in elderly patients: report of 205 treated aneurysms. Neurosurgery 66:711–714. https://doi.org/10.1227/01.NEU.0000367451.59090.D7

Kwinta BM, Klis KM, Krzyzewski RM, Wilk A, Dragan M, Grzywna E, Popiela T (2019) Elective management of unruptured intracranial aneurysms in elderly patients in a high-volume center. World Neurosurg 126:e1343–e1351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2019.03.094

Stiefel MF, Park MS, McDougall CG, Albuquerque FC (2010) Endovascular treatment of unruptured intracranial aneurysms in the elderly: analysis of procedure related complications. J Neurointerv Surg 2:11–15. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnis.2009.001685

Sturiale CL, Brinjikji W, Murad MH, Lanzino G (2013) Endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms in elderly patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke 44:1897–1902. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001524

Hernández-Durán S, Mielke D, Rohde V, Malinova V (2020) Is the unruptured intracranial aneurysm treatment score (UIATS) sensitive enough to detect aneurysms at risk of rupture? Neurosurg Rev. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-020-01246-x

Stumpo V, Latour K, Trevisi G, Valente I, D’Arrigo S, Mangiola A, Olivi A, Sturiale CL (2020) Retrospective application of UIATS recommendations to a multicenter cohort of ruptured intracranial aneurysms: how it would have oriented the treatment choices? World Neurosurg 147:e262–e271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2020.12.041

Juvela S (2019) Treatment scoring of unruptured intracranial aneurysms. Stroke 50:2344–2350. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.025599

Molenberg R, Aalbers MW, Mazuri A, Luijckx GJ, Metzemaekers JDM, Groen RJM, Uyttenboogaart M, van Dijk JMC (2021) The unruptured intracranial aneurysm treatment score as a predictor of aneurysm growth or rupture. Eur J Neurol 28:837–843. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.14636

Hilditch CA, Brinjikji W, Tsang AC, Nicholson P, Kostynskyy A, Tymianski M, Krings T, Radovanovic I, Pereira VM (2018) Application of PHASES and ELAPSS scores to ruptured cerebral aneurysms: how many would have been conservatively managed? J Neurosurg Sci. doi: 10.23736/S0390-5616.18.04498-3

Neyazi B, Sandalcioglu IE, Maslehaty H (2019) Evaluation of the risk of rupture of intracranial aneurysms in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage according to the PHASES score. Neurosurg Rev 42:489–492. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-018-0989-2

Lindgren AE, Koivisto T, Bjorkman J, von Und Zu Fraunberg M, Helin K, Jaaskelainen JE, Frosen J (2016) Irregular shape of intracranial aneurysm indicates rupture risk irrespective of size in a population-based cohort. Stroke 47:1219–1226. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.012404

Bender MT, Wendt H, Monarch T, Beaty N, Lin L-M, Huang J, Coon A, Tamargo RJ, Colby GP (2018) Small aneurysms account for the majority and increasing percentage of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a 25-year, single institution study. Neurosurgery 83:692–699. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuros/nyx484

Korja M, Kivisaari R, Rezai Jahromi B, Lehto H (2018) Size of ruptured intracranial aneurysms is decreasing: twenty-year long consecutive series of hospitalized patients. Stroke 49:746–749. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.019235

Johnston SC (2018) Leaving tiny, unruptured intracranial aneurysms untreated: why is it so hard? JAMA Neurol 75:13–14. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.2559

Malhotra A, Wu X, Forman HP, Matouk CC, Gandhi D, Sanelli P (2018) Management of tiny unruptured intracranial aneurysms: a comparative effectiveness analysis. JAMA Neurol 75:27–34. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.3232

Zanaty M, Daou B, Chalouhi N, Starke RM, Jabbour P, Hasan D (2016) Evidence that a subset of aneurysms less than 7 mm warrant treatment. J Am Heart Assoc 5. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.116.003936

Tulamo R, Frosen J, Hernesniemi J, Niemela M (2018) Inflammatory changes in the aneurysm wall: a review. J Neurointerv Surg 10:i58–i67. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnis.2009.002055.rep

Lv N, Karmonik C, Chen S, Wang X, Fang Y, Huang Q, Liu J (2019) Relationship between aneurysm wall enhancement in vessel wall magnetic resonance imaging and rupture risk of unruptured intracranial aneurysms. Neurosurgery 84:E385–E391. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuros/nyy310

Roa JA, Sabotin RP, Varon A, Raghuram A, Patel D, Morris TW, Ishii D, Lu Y, Hasan DM, Samaniego EA (2020) Performance of aneurysm wall enhancement compared with clinical predictive scales: PHASES, ELAPSS, and UIATS. World Neurosurg 147:e538–e551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2020.12.123

Qi H, Liu X, Liu P, Yuan W, Liu A, Jiang Y, Li Y, Sun J, Chen H (2019) Complementary roles of dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging and postcontrast vessel wall imaging in detecting high-risk intracranial aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 40:490–496. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A5983

Skodvin TO, Evju O, Helland CA, Isaksen JG (2018) Rupture prediction of intracranial aneurysms: a nationwide matched case-control study of hemodynamics at the time of diagnosis. J Neurosurg 129:854–860. https://doi.org/10.3171/2017.5.JNS17195

Varble N, Rajabzadeh-Oghaz H, Wang J, Siddiqui A, Meng H, Mowla A (2017) Differences in morphologic and hemodynamic characteristics for “PHASES-based” intracranial aneurysm locations. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 38:2105–2110. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A5341

Skodvin TO, Evju O, Sorteberg A, Isaksen JG (2019) Prerupture intracranial aneurysm morphology in predicting risk of rupture: a matched case-control study. Neurosurgery 84:132–140. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuros/nyy010

Woodworth GF, Baird CJ, Garces-Ambrossi G, Tonascia J, Tamargo RJ (2009) Inaccuracy of the administrative database: comparative analysis of two databases for the diagnosis and treatment of intracranial aneurysms. Neurosurgery 65:251–257. https://doi.org/10.1227/01.NEU.0000347003.35690.7A

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: JC. Methodology: JF and JC. Formal analysis and investigation: JF. Data acquisition: all authors. Writing—original draft preparation: JF and JC. Writing—review and editing: all authors. Supervision: JC

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Boards.

Consent to participate

Given the retrospective nature of the study and the absence of intervention as part of the study, patient consent was institutionally waived.

Consent for publication

No identifying information was included in the study; therefore, consent to publish was waived.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Feghali, J., Gami, A., Xu, R. et al. Application of unruptured aneurysm scoring systems to a cohort of ruptured aneurysms: are we underestimating rupture risk?. Neurosurg Rev 44, 3487–3498 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-021-01523-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-021-01523-3