Abstract

Introduction

The recently released classification has revised the nosology of tremor, defining essential tremor (ET) as a syndrome and fueling an enlightened debate about some newly conceptualized entities such as ET-plus. As a result, precise information of demographics, clinical features, and about the natural history of these conditions are lacking.

Methods

The ITAlian tremor Network (TITAN) is a multicenter data collection platform, the aim of which is to prospectively assess, according to a standardized protocol, the phenomenology and natural history of tremor syndromes.

Results

In the first year of activity, 679 patients have been recruited. The frequency of tremor syndromes varied from 32% of ET and 41% of ET-plus to less than 3% of rare forms, including focal tremors (2.30%), task-specific tremors (1.38%), isolated rest tremor (0.61%), and orthostatic tremor (0.61%). Patients with ET-plus were older and had a higher age at onset than ET, but a shorter disease duration, which might suggest that ET-plus is not a disease stage of ET. Familial aggregation of tremor and movement disorders was present in up to 60% of ET cases and in about 40% of patients with tremor combined with dystonia. The body site of tremor onset was different between tremor syndromes, with head tremor being most commonly, but not uniquely, associated with dystonia.

Conclusions

The TITAN study is anticipated to provide clinically relevant prospective information about the clinical correlates of different tremor syndromes and their specific outcomes and might serve as a basis for future etiological, pathophysiological, and therapeutic research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Tremor is deemed to be the commonest movement disorder. A population study performed in Northern Italy found tremor syndromes to be the most frequent movement disorder with a prevalence of 14.5% in people aged > 50 years, followed by restless legs syndrome (10.8%) and parkinsonism (6.95%) [1]. Different disorders can present with tremor and they span from very common conditions, including enhancement of physiological tremor (EPT), which is usually transient and non-symptomatic [2], to rare forms of tremor [3]. Probably being the commonest form of tremor seen in clinical practice, Essential Tremor (ET) has an estimated prevalence of 1% of the general population and has been formerly construed to be a mono-symptomatic condition with an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance and characterized by a slow progression of tremor intensity with age [4]. Despite its relative frequency, research efforts into the identification of key pathophysiologic markers and of a defined genetic etiology have been mostly inconclusive [5]. This probably owes to the fact ET has been over-diagnosed with the inclusion of patients in whom other clinical features, such as dystonia, were missed as well as of patients with other forms of tremor (i.e., isolated tremors of the head/voice or even orthostatic tremor), which are instead likely driven by a different pathophysiology [5, 6].

Following this uncertainty, in 2018, the Tremor Task Force of the International Parkinson’s and Movement Disorders Society (IPMDS) published a new tremor classification [7], the structure of which is based on two axes: clinical features (axis I) and etiology (axis II). Accordingly, ET has been re-conceptualized as a clinical syndrome (axis I), rather than as a single disease entity, consisting of an isolated bilateral action tremor of the upper limbs with a duration of at least 3 years [7]. Furthermore, the construct of “ET-plus” was introduced for those patients fulfilling the criteria of ET but also having either a rest tremor or additional “soft signs” that do not suffice to make an alternative diagnosis [7]. Compared to previous definitions of ET, recent studies have suggested that only 15 [8] to 50% [9] of patients would be classified as ET with all the remaining showing additional soft signs and therefore fulfilling the criteria of ET-plus. The high discrepancy between these figures probably owes to the retrospective nature of these studies and therefore precise frequency estimates of ET, ET-plus, and other tremor syndromes are currently unknown. Similarly, precise information of demographics, clinical features, and about the natural history of these conditions are lacking and are highly warranted. In view of the new classification that has revised the nosology of tremor syndromes [7], a longitudinal multicenter collection of accurate and reliable clinical information would increase our understanding of these conditions.

Here, we describe The ITAlian tremor Network (TITAN), a multicenter data collection platform, the aim of which is to prospectively assess the phenomenology and natural history of tremor syndromes and to serve as a basis for future etiological, pathophysiological, and therapeutic research. The TITAN study is also likely to facilitate the dissemination and implementation of the new classification of tremor [7], which is crucial to harmonize the diagnosis of tremor syndromes across centers and to ensure correct recruitment of patients in dedicated clinical trials. In this work, we present the study design, methods and preliminary findings obtained from a large cohort of patients with tremor upon their baseline assessment.

Methods

Study design

The TITAN study has been proposed by the Department of Medicine, Surgery and Dentistry “Scuola Medica Salernitana”, Neuroscience section, University of Salerno, Baronissi, Italy, and approved by the ethic committee of the coordinator center (study approval n.33_r.p.s.o._02/10/2020). In the first year of activity, 30 movement disorder centers distributed throughout Italy have adhered to the TITAN study.

The TITAN study consists of two phases: (1) a transversal phase aimed to assess the frequency and clinical correlates of different tremor syndromes; and (2) a longitudinal phase consisting of annual follow-up visits aimed to assess the natural history of different tremor syndromes. The longitudinal phase duration is set to 10 years.

A virtual investigator meeting was held on January 2021 to recapitulate inclusion criteria, discuss the new tremor classification, explain the study related activities and standard operating procedures, and discuss potential sources of data errors. The registration of the meeting is made available to all participating sites. Patients’ information are recorded into a web-based encrypted anonymised system within the web site of the Fondazione Limpe per il Parkinson ONLUS (http://www.fondazionelimpe.it/) that promoted the study and is only responsible for data handling and the maintenance of the online portal, which complies with the General Data Protection Regulation. The principal investigator of the study (RE) is responsible for the conduct and reporting of the research project and for managing, monitoring, and ensuring the integrity of any collaborative relationships. Sharing the deidentified dataset will be considered on a case-by-case basis, upon reasonable request addressed to the principal investigator (rerro@unisa.it).

Inclusion criteria

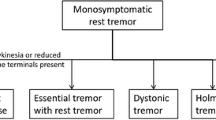

All subjects aged > 18 years with any tremor syndromes but the ones in the context of a clinical diagnosis of parkinsonism (i.e., presence of bradykinesia with either rest tremor or rigidity) [10] will be recruited upon signature of a dedicated consent form. Informed consent is an unconditional prerequisite for patient participation in the study, and data protection and privacy regulations are observed in capturing, forwarding, processing, and storing participant data. Participants are free to withdraw from the study at any time; unless otherwise requested by the participant, all data obtained up to that point will be retained.

Core evaluations

Core assessments include the collection of demographic data (sex and age at evaluation), family history for tremor or any other neurologic disorders, age at onset, tremor distribution at onset, task-specificity at onset, presence of sensory-trick or position-dependence at evaluation, diagnosis according to the 2018 IPMDS classification of tremor, presence of “soft signs” (a free text tab is present on the portal to specify the soft sign(s)) or of associated features, and information about eventually performed imaging studies. Moreover, core assessments include the Essential Tremor Rating Assessment Scale (TETRAS) [11]. Since TETRAS does not capture rest tremor and in order to homogenize comparisons among different tremor syndromes including ET-plus that might in fact present with a rest component, an item assessing rest tremor was added to the scale. It scores rest tremor identically to action tremor (i.e., from 0 = no tremor to 4 = tremor is > 20-cm amplitude) during two different conditions (sitting and walking). Moreover, in order to assess the influence of motor patterns on tremor upon drawing the Archimedes spirals, the relative item was duplicated to have subjects drawing the spirals clockwise and anti-clockwise for each hand. Because of these implementations, we refer to this scoring tool as modified TETRAS (mTETRAS).

Finally, core assessments include the scale for the assessment and rating of ataxia (SARA) [12], the Quality of Life in Essential Tremor Questionnaire (QUEST) [13], and the EuroQol-5D instrument and a collection of previous/current treatments for tremor along with patient-reported outcomes according to the Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) Scale-Improvement (CGI-I).

Ancillary evaluations

Optional evaluations include the MOntreal Cognitive Assessment (MOCA) [14], the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [15], and a customized questionnaire to assess the presence of prodromal symptoms of Parkinson’s disease [16]. Moreover, optional assessments include a video recording of the core-evaluation, an electrophysiologic study, and a collection of a blood sample for future genetic studies.

It is possible for all participating sites to propose ancillary studies that will be discussed and eventually approved by the scientific board of the TITAN study, with the relative assessment procedures/instruments made available on the online platform.

Analysis of baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the enrolled population

Statistical analysis herein presented has been performed by STATA 11 package using descriptive statistics (t-test, chi-squared test, one-way ANOVA, and post hoc tests as appropriate); p < 0.05 deemed as significant. Data were expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD) unless otherwise indicated.

Results

By 31 January 2022, 679 patients were recruited. For 12 patients (1.77%), there were missing data precluding the correct diagnostic allocation and 14 patients (2.06%) were diagnosed with tremor combined with parkinsonism, which represents an exclusion criterion: these records were therefore excluded, leaving a sample of 653 patients (348 males and 305 females) with a mean age (± SD) at evaluation of 67.63 + 12.25 years that is herein described.

ET-plus represented the most common diagnosis (41.34%), followed by ET (32.01%) and combined tremors (14.55%). Among the latter, 89 patients (93.68%) had tremor combined with dystonia (i.e., including both dystonic tremors and tremor associated with dystonia, definitions that are based on the relative distribution of dystonia with respect of tremor, as per consensus [7]), whereas in 3 patients (3.15%), it was associated with ataxia or with a complex epileptic syndrome each. The breakdown of diagnostic allocations is depicted in Table 1, whereas Table 2 details the soft signs in patients with ET-plus.

Preliminary descriptive analyses have been performed to compare the three most prevalent tremor syndromes, namely ET, ET-plus and tremor combined with dystonia (Table 3). Whereas sex distribution was relative homogenous in ET and ET-plus, a higher proportion of females were found to have tremor combined with dystonia (χ2 = 14.91; p < 0.01; Table 3). These patients were younger than both ET and ET-plus, and the latter were the oldest between the three groups (F = 7.19; p < 0.01; Table 3). Significant differences in terms of age at onset were also found between the three groups (F = 5.89; p = 0.05; Table 3) with ET-plus having the higher age at onset, whereas disease duration was longer in ET than in the other two groups (F = 6.89; p < 0.01). Family history for either tremor (χ2 = 17.03; p < 0.01; Table 3) or any movement disorders (χ2 = 11.11; p < 0.01; Table 3) was much more commonly reported by ET and ET-plus patients than patients with tremor combined with dystonia. Head tremor at onset was reported in a minority of patients with ET and ET-plus as compared to about 20% of patients with tremor combined with dystonia (χ2 = 46.67; p < 0.01; Table 3).

Discussion

Although a number of works [8, 9, 17,18,19,20,21,22] have been published after the release of the new tremor classification [7], most of which focused on the re-classification of formerly diagnosed patients with ET, the data herein presented provide the first accurate overview of different tremor syndromes, based on the baseline cross-sectional analysis of a prospective, multi-center assessment of patients with tremor.

Frequency figures of tremor disorders with regard to ET and ET-plus are largely in agreement with previously published studies [8, 9, 17,18,19,20,21,22], confirming the suggestion that ET-plus is more common than ET. Previous studies reported ET-plus frequency to range between about 50 to 85% of “ET” cases [8, 9, 17,18,19,20,21,22]. This large range across studies might be due to two main reasons: (1) the recruitment in tertiary movement disorder centers, which might have led to selection biases [23]; and (2) the fact that all these studies had a retrospective design, attempting a diagnostic reclassification based on medical record review. Our result of ET-plus representing about 56% of “ET cases” conservatively places at the lower boundary of the reported range and might be more representative of the entire population of ET-like tremors because one of the strengths of the TITAN study stands in its multi-center design, which involves both secondary and tertiary movement disorder centers and thus minimizes to some extent the risk of recruitment bias. Moreover, the figures here provided are based on the assessment of patients following the new tremor classification. Of note, this is the first study providing relative frequency of tremor syndromes beyond ET and ET-plus, therefore including rarer forms including isolated segmental action tremors, focal and task-specific tremors, and orthostatic tremor. It should be also noted that the commonest form of tremor (i.e., EPT) was found in less than 2% of our patients: this result, which would seem to contrasts with the conception that EPT is the commonest tremor [1], is easily explained by the fact that this form of tremor is usually non-symptomatic and subjects with EPT do not generally seek medical advice.

When looking at the types and frequency of soft signs associated with ET-plus, rest tremor was found to be largely the commonest (about 50% of cases), followed by questionable dystonia (about 11%) and undetermined slowing (about 9% of cases). These results are broadly in agreement with the majority of studies [17, 21, 22] but not with Pandey and Bhattad [19], who in their prospective assessment of ET-plus cases found rest tremor in only 2 out of 45 ET-plus cases (4.44%). The latter result might be due to the single-center recruitment as well as to the specific expertise of the raters (focused on dystonia) [24], limitations that are arguably minimized in the TITAN study because of its multi-center design, as mentioned above.

Sex distribution of ET (and ET-plus) is in line with previous findings [4], as it is for tremor combined with dystonia [25], which was found to be more common in females, recapitulating sex distribution of adult-onset dystonia in general [26].

Interestingly, a positive family history, particularly but not only for tremor, was found in about 50–60% of cases with ET and ET-plus which reinforces the concept of a genetic susceptibility in both syndromes, despite the largely negative efforts pursued in the past to find a genetic cause of ET [5]. Conversely, family history for tremor was much less common in patients with dystonia, although it was present in about 20% of cases. Given the self-report of family history, it is impossible to ascertain whether in these family members tremor was present in addition to dystonia or was an isolated finding. The latter hypothesis would support the concept of dystonia being a phenotypic continuum between abnormal posturing and tremor [27], with the two features being associated in some cases. Beyond this speculation, our results remark on the fact that tremor is part of the phenotypic spectrum of dystonia and therefore, dystonia should be carefully looked for when assessing tremulous patients to avoid misdiagnosis [28].

Of note, patients with ET-plus were older and had a higher age at onset than ET cases. Conversely, the latter had longer disease duration than the former. These results are in contrast with Louis et al. who found ET-plus cases to be older than ET as a function of longer disease duration, and therefore suggested ET-plus being a “disease stage” of ET [17]. Our results do not support this proposal and would rather suggest that ET-plus represents a group of different entities, which, at least in cases with onset in the elderly, might be linked to pathological aging and arguably less dependent on genetic predisposition [29].

Another novelty of the new tremor classification is the removal of patients with isolated focal tremor of the head and voice from the rubric of ET [7]. However, our results show that tremor at onset might involve other body regions beyond the arms in a minority of patients with ET and ET-plus. Therefore, although head tremor is more common in dystonia and patients with isolated head tremor are more likely to develop overt dystonia during the disease course [30], this would not always be the rule. Longitudinal assessments of patients with isolated focal tremors of the head or voice in this study will eventually clarify whether there are clinical features predicting the final diagnostic allocation.

We acknowledge some limitations. We cannot entirely exclude a recruitment bias that is inherent to studies without a population-based design. However, the inclusion of both secondary and tertiary movement disorder centers might have, at least in part, attenuated this risk and therefore might provide frequency figures of tremor syndromes that should be more realistic than those obtained in single-center studies. Moreover, we acknowledge that the diagnosis of tremor syndromes is made on clinical basis given the lack of available biomarkers, and this might carry the risk of misdiagnosis in a proportion of patients. However, we strictly adhered to the current classification [7], which does not require any additional testing for the formal definition of the proposed tremor syndromes [6]. Finally, there are no operational criteria for the definition of “soft signs” and their interpretation is, per consensus, subjective and left to the investigator [7]. This might clearly represent a source of ambiguity [31]. However, we note that (1) the frequency of ET-plus herein reported is in line with previous studies and (2) rest tremor, which was the most frequent soft sign in this as well as in many other studies, does not strictly represent a finding “of uncertain relationship to tremor” [7], thus minimizing the ambiguity regarding the highly debated construct of ET-plus [32].

In summary, we have here presented the rationale and design of the TITAN study, the preliminary results of which can already inform about the relative frequency and main clinical features of the newly conceptualized tremor syndromes. The TITAN study is anticipated to provide clinically relevant prospective information about the clinical correlates of different tremor syndromes, their specific outcomes, and the eventual transition across different diagnostic allocations and also to generate hypotheses for future investigations.

Change history

21 August 2022

Missing Open Access funding information has been added in the Funding Note.

20 June 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-022-06216-3

References

Wenning GK, Kiechl S, Seppi K, Müller J, Högl B, Saletu M, Rungger G, Gasperi A, Willeit J, Poewe W (2005) Prevalence of movement disorders in men and women aged 50–89 years (Bruneck Study cohort): a population-based study. Lancet Neurol 4(12):815–820

Elble RJ (1986) Physiologic and essential tremor. Neurology 36(2):225–231

Erro R, Reich SG (2022) Rare tremors and tremors occurring in other neurological disorders. J Neurol Sci 435:120200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2022.120200

Haubenberger D, Hallett M (2018) Essential tremor. N Engl J Med 378(19):1802–1810

Espay AJ, Lang AE, Erro R, Merola A, Fasano A, Berardelli A, Bhatia KP (2017) Essential pitfalls in “essential” tremor. Mov Disord 32(3):325–331

Erro R, Fasano A, Barone P, Bhatia KP. Milestones in tremor research: 10 years later. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/mdc3.13418

Bhatia KP, Bain P, Bajaj N, Elble RJ, Hallett M, Louis ED, Raethjen J, Stamelou M, Testa CM, Deuschl G; Tremor Task Force of the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society. Consensus Statement on the classification of tremors. from the task force on tremor of the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society. Mov Disord. 2018;33(1):75–87.

Rajalingam R, Breen DP, Lang AE, Fasano A (2018) Essential tremor plus is more common than essential tremor: insights from the reclassification of a cohort of patients with lower limb tremor. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 56:109–110

Prasad S, Pal PK (2019) Reclassifying essential tremor: implications for the future of past research. Mov Disord 34(3):437

Postuma RB, Berg D, Stern M, Poewe W, Olanow CW, Oertel W, Obeso J, Marek K, Litvan I, Lang AE, Halliday G, Goetz CG, Gasser T, Dubois B, Chan P, Bloem BR, Adler CH, Deuschl G (2015) MDS clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 30(12):1591–1601

Elble R, Comella C, Fahn S, Hallett M, Jankovic J, Juncos JL et al (2012) Reliability of a new scale for essential tremor. Mov Disord 27(12):1567–1569

Schmitz-Hübsch T, du Montcel ST, Baliko L, Berciano J, Boesch S, Depondt C, Giunti P, Globas C, Infante J, Kang JS, Kremer B, Mariotti C, Melegh B, Pandolfo M, Rakowicz M, Ribai P, Rola R, Schöls L, Szymanski S, van de Warrenburg BP, Dürr A, Klockgether T, Fancellu R (2006) Scale for the assessment and rating of ataxia: development of a new clinical scale. Neurology 66(11):1717–1720

Tröster AI, Pahwa R, Fields JA, Tanner CM, Lyons KE (2005) Quality of life in Essential Tremor Questionnaire (QUEST): development and initial validation. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 11(6):367–373

Santangelo G, Siciliano M, Pedone R, Vitale C, Falco F, Bisogno R, Siano P, Barone P, Grossi D, Santangelo F, Trojano L (2015) Normative data for the Montreal cognitive assessment in an Italian population sample. Neurol Sci 36(4):585–591

Costantini M, Musso M, Viterbori P, Bonci F, Del Mastro L, Garrone O, Venturini M, Morasso G (1999) Detecting psychological distress in cancer patients: validity of the Italian version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Support Care Cancer 7(3):121–127

Pilotto A, Heinzel S, Suenkel U, Lerche S, Brockmann K, Roeben B, Schaeffer E, Wurster I, Yilmaz R, Liepelt-Scarfone I, von Thaler AK, Metzger FG, Eschweiler GW, Postuma RB, Maetzler W, Berg D (2017) Application of the movement disorder society prodromal Parkinson’s disease research criteria in 2 independent prospective cohorts. Mov Disord 32(7):1025–1034

Louis ED, Huey ED, Cosentino S (2021) Features of “ET plus” correlate with age and tremor duration: “ET plus” may be a disease stage rather than a subtype of essential tremor. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 91:42–47

Iglesias-Hernandez D, Delgado N, McGurn M, Huey ED, Cosentino S, Louis ED (2021) “ET Plus”: instability of the diagnosis during prospective longitudinal follow-up of essential tremor cases. Front Neurol 12:782694

Pandey S, Bhattad S (2021) Soft signs in essential tremor plus: a prospective study. Mov Disord Clin Pract 8(8):1275–1277

Campbell JM, Ballard J, Duff K, Zorn M, Moretti P, Alexander MD, Rolston JD (2022) Balance and cognitive impairments are prevalent and correlated with age in presurgical patients with essential tremor. Clin Park Relat Disord 6:100134

Peng J, Li N, Li J, Duan L, Chen C, Zeng Y, Xi J, Jiang Y, Peng R. Reclassification of patients with tremor syndrome and comparisons of essential tremor and essential tremor-plus patients. J Neurol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-022-10985-4

Bellows ST, Jankovic J (2021) Phenotypic features of isolated essential tremor, essential tremor plus, and essential tremor-Parkinson’s disease in a movement disorders clinic. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y) 11:12

Louis ED, Hernandez N, Michalec M (2015) Prevalence and correlates of rest tremor in essential tremor: cross-sectional survey of 831 patients across four distinct cohorts. Eur J Neurol 22(6):927–932. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.12683

Becktepe J, Gövert F, Balint B, Schlenstedt C, Bhatia K, Elble R, Deuschl G (2021) Exploring Interrater disagreement on essential tremor using a standardized tremor elements assessment. Mov Disord Clin Pract 8(3):371–376

Erro R, Rubio-Agusti I, Saifee TA, Cordivari C, Ganos C, Batla A, Bhatia KP (2014) Rest and other types of tremor in adult-onset primary dystonia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 85(9):965–968

Defazio G, Esposito M, Abbruzzese G, Scaglione CL, Fabbrini G, Ferrazzano G, Peluso S, Pellicciari R, Gigante AF, Cossu G, Arca R, Avanzino L, Bono F, Mazza MR, Bertolasi L, Bacchin R, Eleopra R, Lettieri C, Morgante F, Altavista MC, Polidori L, Liguori R, Misceo S, Squintani G, Tinazzi M, Ceravolo R, Unti E, Magistrelli L, Coletti Moja M, Modugno N, Petracca M, Tambasco N, Cotelli MS, Aguggia M, Pisani A, Romano M, Zibetti M, Bentivoglio AR, Albanese A, Girlanda P, Berardelli A (2017) The Italian Dystonia Registry: rationale, design and preliminary findings. Neurol Sci 38(5):819–825

Albanese A, Sorbo FD (2016) Dystonia and tremor: the clinical syndromes with isolated tremor. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y) 6:319

Erro R, Schneider SA, Stamelou M, Quinn NP, Bhatia KP (2016) What do patients with scans without evidence of dopaminergic deficit (SWEDD) have? New evidence and continuing controversies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 87(3):319–323

Deuschl G, Petersen I, Lorenz D, Christensen K (2015) Tremor in the elderly: essential and aging-related tremor. Mov Disord 30(10):1327–1334

Ferrazzano G, Belvisi D, De Bartolo MI, Baione V, Costanzo M, Fabbrini G, Defazio G, Berardelli A, Conte A (2022) Longitudinal evaluation of patients with isolated head tremor. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 94:10–12

Fearon C, Espay AJ, Lang AE, Lynch T, Martino D, Morgante F, Quinn NP, Vidailhet M, Fasano A (2019) Soft signs in movement disorders: friends or foes? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 90(8):961–962. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2018-318455

Louis ED, Bares M, Benito-Leon J, Fahn S, Frucht SJ, Jankovic J, Ondo WG, Pal PK, Tan EK (2020) Essential tremor-plus: a controversial new concept. Lancet Neurol 19(3):266–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30398-9

Acknowledgements

We are extremely grateful to Lucia Faraco and the staff of the “Fondazione Limpe per il Parkinson ONLUS” for the continuing support in the maintenance of the portal and for coordinating the activities between centers.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Salerno within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Cristiano Sorrentino, Department of Medicine, Surgery and Dentistry “Scuola Medica Salernitana”, Neuroscience Section, University of Salerno, Baronissi (SA), Italy

Maria Russo, MD, Department of Medicine, Surgery and Dentistry “Scuola Medica Salernitana”, Neuroscience Section, University of Salerno, Baronissi (SA), Italy

Stefano Gipponi, Department of Clinical and Experimental Sciences, Neurology Unit, University of Brescia, Italy

Riccardo Morandi, Department of Clinical and Experimental Sciences, Neurology Unit, University of Brescia, Italy

Filippo Iorillo, Clinical Neurophysiology Unit, Cardarelli Hospital, Naples, Italy

Gabriella De Joanna, Clinical Neurophysiology Unit, Cardarelli Hospital, Naples, Italy

Lorena Belli, Neuromed Institute IRCCS, Pozzilli (IS), Italy

Luana Gilio, Neuromed Institute IRCCS, Pozzilli (IS), Italy

Silvia Gallo, Department of Translational Medicine, Movement Disorders Centre, Neurology Unit, University of Piemonte Orientale, Novara, Italy

Francesca Vignaroli, Department of Translational Medicine, Movement Disorders Centre, Neurology Unit, University of Piemonte Orientale, Novara, Italy

Massimo Sciarretta, Neurology Unit, Department of Medical Area, ASST Pavia

Gabriele Bellavia, Neurology Unit, Department of Medical Area, ASST Pavia

Tiziana Benzi Markushi, IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San Martino, Genova, Italy

Luca Angelini, Department of Human Neurosciences, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy

Simone Aramini, Department of Advanced Medical and Surgical Sciences, Università della Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli”, Napoli, Italy

Maria Concetta Altavista, Neurology Unit,San Filippo Neri Hospital ASL Roma1, Rome, Italy

Andrea Fasanelli, Primary Care, APSS Trento, Italy

Simone Regalbuto, Parkinson's Disease and Movement Disorders Unit, IRCCS Mondino Foundation, Pavia, Italy

Gianluigi Rosario Palmieri, Department of Neurosciences and Reproductive and Odontostomatological Sciences, Federico II University, Naples, Italy

Roberta Vitaliani, Unit of Neurology, Department of Neuro-cardio-vascular, Ca' Foncello Hospital, Treviso, Italy

Bianchi Marta, Unit of Neurology- Department of Medical Area. Esine Hospital, Esine (BS), Italy

Laura Bonanni, Department of Medicine and Aging Sciences, University G. d’Annunzio of Chieti-Pescara, Italy

Sandy Maria Cartella, Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, University of Messina, Italy

Vincenzo Di Lazzaro, Neurology Unit, Campus Bio-Medico University, Hospital Foundation, Rome, Italy; Unit of Neurology, Neurophysiology, Neurobiology, Department of Medicine, Università Campus Bio-Medico di Roma, Rome, Italy

Giulia Franco, Neurology Unit, Department of Neuroscience, Dino Ferrari Center, Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan, Italy

Federica Arienti, Neurology Unit, Department of Neuroscience, Dino Ferrari Center, Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan, Italy

Giovanni Mostile, University of Catania, Department “G.F. Ingrassia”, Section of Neurosciences, Catania, Italy; Oasi Research Institute—IRCCS, Troina, Italy

Stefano Zoccolella, Neurosensory Department, Neurology Unit, San Paolo Hospital, ASL Bari, Italy

Anna Castagna, Centro Disturbi del movimento-SAFLo IRCCS Fondazione Don carlo Gnocchi Onlus Milano, Italy

Laura Maria Raglione, Unit of Neurology of Florence, Central Tuscany Local Health Authority, Florence, Italy

Roberto Ceravolo, Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, University of Pisa, Pisa, Italy

Francesca Spagnolo, Neurological Department, A. Perrino’s Hospital, Brindisi, Italy

Susanne Buechner, Department of Neurology/Stroke Unit, General Hospital of Bolzano, Italy

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Roberto Erro receives royalties from publication of Case Studies in Movement Disorders—Common and Uncommon Presentations (Cambridge University Press, 2017) and of Paroxysmal Movement Disorders (Springer, 2020). He has received consultancies from Sanofi and honoraria for speaking from the International Parkinson's Disease and Movement Disorders Society. Paolo Barone received consultancies as a member of the advisory board for Zambon, Lundbeck, UCB, Chiesi, Abbvie, and Acorda. Anna De Rosa received consultancies from Lundbeck, and from Bial as a member of advisory board. Andrea Pilotto received grant support from Ministry of Education, Research and University (MIUR) and IMI H2020 Initiative (IDEA-FAST project- MI2-2018-15-06), received research support from Zambon SrL Italy and Bial italy; he received speaker honoraria from Abbvie, Biomarin, Bial and Zambon Pharmaceuticals. Alessandro Padovani received grant support from Ministry of Health (MINSAL) and Ministry of Education, Research and University (MIUR), from CARIPLO Foundation; personal compensation as a consultant/scientific advisory board member for Biogen 2019-2020-2021 Roche 2019-2020 Nutricia 2020-2021 General Healthcare (GE) 2019; he received honoraria for lectures at meeting ADPD2020 from Roche, Lecture at meeting of the Italian society of Neurology 2020 from Biogen and from Roche, Lecture at meeting AIP 2020 and 2021 from Biogen and from Nutricia, Educational Consulting 2019-2020-2021 from Biogen. Lazzaro di Biase has received a speaker honoraria from Bial, consultant honoraria from Abbvie and research funding from Zambon, is the scientific director and one of the shareholders of Brain Innovations Srl, a University spinoff of Campus Bio-Medico University of Rome. All other authors have nothing to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: Originally, the article was published with an error. The affiliation of the author Giulia Paparella should only be "Neuromed Institute IRCCS, Pozzilli, IS, Italy”.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Erro, R., Pilotto, A., Esposito, M. et al. The Italian tremor Network (TITAN): rationale, design and preliminary findings. Neurol Sci 43, 5369–5376 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-022-06104-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-022-06104-w