Abstract

Objective

The objective of this study is to describe the first series of spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA) in Rio de Janeiro, whose population has a high proportion of mixed Portuguese and African ancestry.

Methods

We reviewed the medical records of patients with progressive ataxia evaluated at the Sarah Network of Rehabilitation Hospitals (Rio de Janeiro). Clinical course, genetic tests for hereditary ataxia, brain MRI, and electroneuromyography were analyzed.

Results

SCA was confirmed in 128 individuals, one-third of African descendants. SCA3 predominated (83.6%), followed by SCA7 (7%); SCA2 (3.9%); SCA1, SCA6, and SCA8 (1.6% each); and SCA10 (0.8%). Dysphagia, pyramidal signs, and neurogenic bladder occurred frequently. Oculomotor disorders occurred with SCA3, SCA7, SCA2, and SCA1; peripheral neuropathies with SCA3 and SCA1; extrapyramidal syndromes with SCA3, SCA7, and SCA2; bilateral visual impairment with SCA7; and epilepsy with SCA10. Mobility assistance was required in 75% after 11 years and wheelchair in 25%. The Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia scores at the last follow-up varied from 2 to 37 (median = 14.50) and correlated positively with duration of the disease. In SCA3, a higher CAG repeats correlated with a lower age at onset. African ethnicity was associated with earlier onset, regardless of CAG repeats. The main brain MRI abnormality was cerebellar atrophy, isolated or associated with brainstem atrophy, “hot cross bun” sign, or brain atrophy. Linear T2 hyperintensity along the medial margin of the globus pallidus occurred in SCA3, SCA2, SCA1, and SCA7. ENMG confirmed peripheral neuropathy in SCA3 and SCA1.

Conclusion

Machado Joseph disease/SCA3 was the most frequent inherited dominant ataxia in Rio de Janeiro. This study revealed new aspects of ethnic influence in the clinical course and new MRI findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cerebellar ataxia is a neurological syndrome that occurs due to injury or dysfunction of the cerebellum and its pathways characterized by incoordination of the limbs and gait, dysarthria, hypotonia, nystagmus, trunk asynergy, and dysdiadochokinesis; its onset may be acute, subacute, or progressive depending on the etiology [1].

Genetically determined ataxias have an insidious onset and a progressive course with different forms of inheritance (autosomal dominant, recessive, X-linked, or mitochondrial); family history is a clue for diagnosis but may be absent or unknown, and the disease, initially classified as sporadic ataxia [2,3,4]. It is essential to exclude acquired causes such as infection; intoxication; deficiency states; metabolic, autoimmune, tumoral, paraneoplastic, and vascular diseases; traumatic brain injury; and congenital malformations [5].

Spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA), an autosomal dominant disease with an estimated prevalence of 3.2/100,000 (1.8–4.6/100,000), comprises a heterogeneous group of rare diseases identified according to their subtypes (SCA 1 to 48) by genetic tests.

The first identified locus (SCA1) was on the short arm of chromosome 6, where an unstable expansion of CAG trinucleotides was identified. After that, the different types of SCA were numbered according to their order of discovery [6,7,8].

Geographic and ethnic differences in the frequency of SCA types occur worldwide [9, 10]. In Brazil, a Latin American country of continental dimensions colonized by the Portuguese, the most frequent spinocerebellar ataxia is SCA3 [11,12,13,14], described initially as Machado Joseph’s Disease in families from the Azores Islands. However, most of the Brazilian studies were from the South region, where the population has predominant Caucasian ethnicity by European immigration. Few patients were from Rio de Janeiro, located in the Southeast region, where more than 50% of the people are of African descent because of the high miscegenation between Portuguese and African slaves.

The objective of this study was to investigate the frequency and clinical and laboratory characteristics of SCA in a cohort of patients from Rio de Janeiro.

Materials and methods

Study design

This is a longitudinal descriptive study with retrospective data collection.

Patient selection

The Sarah Network of Rehabilitation Hospitals—Rio de Janeiro unit opened in 2009, and since then, patients with cerebellar ataxia admitted to the institution have undergone etiological investigation prior to receiving rehabilitation treatment.

An outpatient ataxia clinic was organized in 2018, with the purpose to get together patients with progressive ataxias attended by a multidisciplinary team.

For this study, we reviewed medical records of patients who attended the outpatient ataxia clinic between January 2018 and December 2019. Only individuals over 16 years with progressive cerebellar ataxia and genetic testing were included.

Patients with ataxia due to post stroke cerebellar syndrome, post-TBI care, post neurosurgical treatment, sequelae of congenital malformations, infections, demyelinating, autoimmune disease, or multisystem atrophy are followed in other institutional sectors.

Methods

Laboratory investigation

Cerebellar ataxia was classified as hereditary and sporadic according to family history. Genetic causes were investigated in both groups. The laboratory investigation for hereditary ataxia included the following genetic tests available at the institution: SCA1, SCA2, SCA3, SCA6, SCA7, SCA8, SCA10, and SCA17, dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy (DRPLA), Friedreich’s ataxia, ataxia-telangiectasia, fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome, and ataxia with vitamin E deficiency (AVED). Other tests performed were brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), electroneuromyography (ENMG), and the following biological marker and biochemical tests: vitamin E and B12 levels, cholestanol, cholesterol, alpha-fetoprotein, GDF-15, FGF-21, lactate, ammonia, acanthocytes, anti-GAD, antineuronal auto-antibodies, screening for celiac disease (anti-endomysium, anti-tissue transglutaminase), thyroid hormones, and serology for infectious diseases (HIV, syphilis).

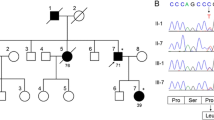

The methods used to test for SCA (SCA1, SCA2, SCA3, SCA6, SCA7, SCA8, SCA10, and SCA17) are described in the supplementary material.

Information collection

Demographic and clinical data extracted from hospital records: date of admission to the hospital, date of last follow-up visit, date of birth, nationality, address, sex, color/race (white, brown, black [African descendant], yellow [Asian], or indigenous), family history of ataxia, year of disease onset, initial symptoms, associated neurological syndromes, and neurological disability at the last follow-up. The cerebellar ataxia was measured by the Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (SARA) [15, 16]. Mobility was classified in four categories: ambulation free, unilateral support, bilateral support and wheel chair use.

Complementary tests

Brain MRI and ENMG performed in the institution or reported in the medical register were reviewed.

Ethical statements

The Research Ethics Committee of the institution approved this research involving human participants (CAAE29452620.0.0000.0022).

Participants provided written informed consent prior to participation.

Statistical analysis

The data were entered into an Excel spreadsheet and analyzed using SPSS software. Percentages means and medians were calculated according to the type of variable. The chi-square test was used for measures of association. The patients were divided into two groups according to the median disease duration to investigate the factors associated with long-term disability. Correlations between variables were determined using the Spearman method. Statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

Results

Overall genetic results

A total of 227 patients with progressive ataxia, most of whom were female, white, and aged between 16 and 84 years (mean = 46 years), were selected for the study. Genetic disease was defined in 169 patients. Machado Joseph disease (SCA3) and Friedrich’s ataxia were the most frequent causes (Fig. 1). For 58 patients (25.5%), it was no possible to establish etiology with the available complementary investigation tools. Among these patients, 25 had a family history of ataxia, and 33 were classified as sporadic ataxia.

Spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA)

Among the 128 cases of SCA confirmed by molecular tests, Machado Joseph disease/SCA3 predominated (83.6%). Less frequent forms were SCA7 (7%), SCA2 (3.9%); SCA1, SCA6, and SCA8 (1.6%); and SCA10 (0.8%). No cases of SCA17 or DRPLA were identified. Another 19 cases of ataxia with a family history of autosomal dominant inheritance were not confirmed by the available tests.

Polyglutamine repeat expansion

There was polyglutamine repeat expansion among the SCAs investigated in this study, and the most frequent type was CAG expansion. Of the 107 cases of SCA3, it was possible to quantify the number of CAG repeats in 93 cases; the number of repeats ranged from 50 to 78 (mean = 65). In the other 14 cases, there were more than 52 repeats. Among the eight patients with SCA7, CAG repeats ranged from 37 to 59 (mean = 45). In one case, the number was greater than 36. In the four cases of SCA2, the number of CAG repeats was greater than 32; in one case, it was 45. In one case of SCA1, the number of CAG repeats was greater than 38, and in the other, it was 53. In one case of SCA6, there were 24 CAG repeats; in the other, there were 30.

Demographic and clinical data

Table 1 describes the demographic characteristics according to SCA type. In most cases, SCA patients were female (n = 70, 54.6%) and white (n = 90, 70.3%), and the first symptoms of imbalance occurred in the 4th decade of life (mode, mean, and median: 39 years). The frequencies of the decade of onset were as follows: 1st decade (0–10 years), n = 1; 2nd decade, n = 7; 3rd decade, n = 21; 4th decade, n = 44; 5th decade, n = 33; 5th decade, n = 19; 7th decade, n = 3).

Ataxia cerebellar was present in all patients and noncerebellar neurological manifestations were identified in most of them, as described in Table 2. Progressive ataxia and dysphagia, pyramidal signs, and neurogenic bladder symptoms were the most frequent syndromes. Oculomotor disorders occurred in SCA3, SCA7, SCA2, and SCA1. In 30/108 patients with SCA3 (28%) occurred supranuclear ophthalmoplegia with different degrees of severity: 14 had vertical and horizontal gaze palsy, nine had only vertical gaze palsy, and five only horizontal gaze palsy. Most of the patients with vertical gaze palsy presented upgazed palsy. Associations with peripheral neuropathies confirmed by neurophysiological examination and clinically manifesting as predominantly sensory symptoms were identified in SCA3 and SCA1. Extrapyramidal syndromes, such as parkinsonism and dystonia, occurred in cases of SCA3 and SCA7. Bilateral visual deficit due to macular degeneration of the retina was found only in cases of SCA7, and epilepsy occurred in the unique case of SCA10.

Long-term assessment

The severity of the cerebellar ataxia measured by the Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (SARA) and the mobility aid were assessed at the last follow-up, after a median disease duration of 11 years (2 to 32 years). The results about SARA scores are shown at Fig. 2.

The SARA scores analyzed in 75% of the patients (n = 97) varied from 2 to 37 (median = 14.50) (Fig. 2A). The Spearman correlation between SARA scores and time of disease was strongly positive (rho = 0.477) and statistically significant (p = 0.001) (Fig. 2B).

Mobility aid at last follow up was classified as unilateral support (n = 26, 20.3%), bilateral support (n = 37, 28.9%), and wheelchair use (n = 31, 24.2%). Only 34 patients (26, 6%) were able to walk without assistance. Among the patients with a longer disease duration (> 11 years), 44.6% required a wheelchair for mobility, compared with only 8% of the patients with shorter disease duration (< 11 years) (p = 0.000). There was no association between sex or age at onset with loss of gait. Although with an ataxic component, ambulation without assistance was observed in 12.5% of patients with longer disease duration and 37.5% of patients with shorter duration.

Machado Joseph disease/SCA3

Most of the 107 patients with SCA3 were female (57.9%) and white (72.8%), and the mean age at onset was in the fourth decade (40.4 years). The SARA scores analyzed at the last follow-up in 78% of the patients varied from 2 to 37 (median = 14). Eighty-two percent of the patients in this group with longer disease duration required a wheelchair for mobility, compared with 17.9% of those with a disease duration less than 11 years.

The Spearman correlation between age at onset and number of CAG repeats was strongly negative (− 428) and statistically significant (p = 0.000), indicating that the higher the number of CAG repeats was, the earlier the age at onset. No correlation was found between the CAG repeats and the SARA scores (rho = 0.094, p = 0.423).

The age of onset was earlier among patients of African descent than among white patients (mean: 36.59 versus 42.24, p = 0.02). There was no significant difference in the number of CAG repeats between patients of white and African descent.

Complementary exams for SCA

Magnetic resonance imaging

Brain MRI was performed in 106 patients with SCA. Cerebellar atrophy was predominant among the changes found on brain MRI (88.6%).

Isolated cerebellar atrophy occurred in 50 patients (47.1%). Ponto-cerebellar atrophy was seen in 21 patients (19.8%). “Hot cross bun” sign isolated or associated with cerebellar or ponto-cerebellar atrophy occurred in 16 patients (15%). Brain atrophy associated with cerebellar or ponto-cerebellar atrophy was seen in 10 patients (9.4%). Linear T2 hyperintensity along the medial margin of the globus pallidus was seen in two SCA1, one SCA2, six SCA7, and 59 SCA3. The frequency of those brain MRI findings in different types of SCA is described in Table 3.

Figure 3 illustrates those brain MRI abnormalities in SCA.

Brain MRI abnormalities in SCA. A Sagittal T1 SPGR showing anterior vermis atrophy associated with pontine atrophy in patient with SCA3. B, C Axial FLAIR demonstrating atrophy of the upper (arrows) and middle (*) cerebellar peduncles. D Axial T2 showing the “hot cross bun sign” in patient with SCA2. E Coronal T2 showing brain and cerebellar atrophy in patient with SCA7. F Axial DP showing linear hyperintensity in the medial margin of globus pallidus in patient with SCA3

Eletroneuromyography

ENMG was performed in 55 patients with SCA3; the results were abnormal in 41 (74.5%). Neurophysiological changes indicative of polyneuropathy was detected in 28 patients (50.9%), motor neuronopathy in 22 (40%), and radiculopathy in 10 (18.5%).

Polyneuropathies were classified as follows:

-

Sensory and axonal polyneuropathy (n = 6)

-

Sensorimotor axonal polyneuropathy (n = 9)

-

Sensorimotor polyneuropathy with demyelination (n = 1)

-

Sensorimotor polyneuropathy with predominantly sensory and axonal polyneuropathy (n = 11)

-

Sensorimotor polyneuropathy with axonal and demyelinating sensory predominance (n = 1)

Abnormalities in ENMG were also identified in one case of SCA7 (motor neuronopathy) and one case of SCA1 (demyelinating sensorimotor polyneuropathy). Two patients with SCA6 had normal ENMG results.

Discussion

Machado Joseph disease is the most common form of SCA worldwide [9, 10].

It was described in families from São Miguel Island, Azores, Portugal, that immigrated for the USA at the nineteenth century [17, 18]. After introducing molecular biology techniques, the genetic locus associated with Machado Joseph disease was discovered, and the disease became known as SCA3 [19].

In the patients from Rio de Janeiro analyzed in the present study, Machado Joseph disease (SCA3) occurred in 83.6%. This high frequency was surpassed only by the Brazilian series of Jardim and colleagues (2001), in which 89% of patients tested had SCA3; most of the patients belonged to families born in the state of Rio Grande do Sul [11]. In a multicentric Brazilian study, most of the patients were also from the southern region, and among 544 patients tested, 62.5% were diagnosed with SCA3 [13]. Nascimento and colleagues (2019) conducted a study in a single neurological center in the state of Paraná, also in the southern region, and found a lower frequency of SCA3 (45.7%) [14]. The colonization patterns in Brazil differed among regions and states in the same region, which may explain the differences in the frequency of SCA3 in our country.

Countries in which SCA3 is quite rare include Italy (1%) and South Africa (4%).

Other SCA types predominated in Latin American countries, Europe, and Africa: SCA2 in Cantabria (Spain) and Cuba, SCA6 in England and SCA7 in Venezuela, and among black people from South Africa [9, 10, 20]. Interesting, the second most common mutation in RJ, with a population with a high African background, was SCA7 (7%). Among two other Brazilian series from South region with high European ancestry, the second most common type was SCA2 (7.8%) or SCA10 (18.3%) [13, 14]. In RJ, SCA2 affected five patients (3.9%) and SCA10 only one patient (0.78%).

Despite technological advances, Ruano and colleagues (2014) in a systematic review identified considerable variation (20% to 92%) in the frequency of spinocerebellar cases without genetic confirmation in patients tested for the most frequent mutations [9]. Among the 147 patients in Rio de Janeiro with ataxia and a family history of dominant inheritance, only 19 (12.9%) did not have genetic evidence based on available testing. Although this frequency is the lowest in the literature, the lack of available testing for rare types of SCA is a limitation of this study.

From a clinical point of view, SCA manifests as slow and progressive gait changes, limb motor incoordination, and nystagmus, with additional characteristics shown in Table 2 as dysphagia (54,60%), pyramidal syndrome (39,81%), neurogenic bladder (30,06%), ophthalmoplegia (28,12%), and extrapyramidal syndromes (16.40%).

In the 1980s, before recognizing the genetic locus, Anita Harding proposed the phenotypic classification of autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia (ADCA) into three types. In ADCA type I, ataxia is associated with pyramidal, extrapyramidal, and ophthalmoplegia signs; in ADCA type II, ataxia with pigmentary retinal degeneration; and in ADCA type III, pure ataxia [21]. After genetic testing, which allows the identification of 48 subtypes, it is possible to verify that most SCA types belong to the ADCA I type; additionally, other associated manifestations were identified as peripheral neuropathies, myoclonus, psychiatric disorders, narcolepsy, epilepsy, hearing loss, and ictiform plaques. It is also possible to establish phenotypes related to specific subtypes, such as visual deficits in SCA7, myoclonus in SCA14, facial and tongue fasciculations in SCA36, and ictiform plaques in SCA34 [8]. Corroborating data from the literature, 7/9 (78%) SCA7 cases from Rio de Janeiro, presented visual impairment corresponding to ADCA type II. Pure forms of ataxia that correspond to ADCA type III were rare, occurring in 12 patients; of these, nine had SCA3, and one each had SCA2, SCA7, and SCA8. These findings, however, can change throughout the disease. Pure forms have been associated more frequently with SCA types 5, 6, 11, 23, 26, 30, 37, 41, and 45, of which only type 6 has been widely researched [8]. Here, only two patients had SCA6 mutations; one had pure ataxia and the other, ataxia, was associated with dysphagia, pyramidal syndrome, and neurogenic bladder, demonstrating that the phenotype is variable even within the different types of SCAs.

As well documented in the literature [22, 23], we found a negative correlation between the higher number of CAG repeats and the earlier disease onset in SCA3. There was no influence of African ethnicity in the number of CAG repeats, but in the age of onset, there was a significant difference with white patients (p = 0.02). These data indicate that African ethnicity was an independent factor for early onset. Such data have not yet been reported in the literature but should be confirmed in future studies with a greater number of Afro descendants SCA3 patients.

The remarkable neuroradiological finding of SCA is cerebellar atrophy [24], as confirmed here, where this brain abnormality occurred in all SCA types. In patients with SCA3, cerebellar atrophy was isolated or associated with ponto-cerebellar atrophy, the “hot cross bun” sign, and diffuse brain atrophy. Those findings are not pathognomonic of SCA and can occur in other neurodegenerative conditions [25]. Linear T2 hyperintensity along the medial margin of the globus pallidus, indicating degeneration of lenticular fasciculus, was firstly described in 16 patients with SCA3 by Yamada and colleagues (2005) [26]. Later, this MRI finding was confirmed in small series of SCA3 patients [27, 28]. We identified this brain abnormality in 59/73 (80%) in SCA3 patients from Rio de Janeiro. Beyond that, we observed the linear T2 hyperintensity along the medial margin of the globus pallidus in other different SCA types: five SCA7, one SCA2, and in both cases of SCA1. Those finding not yet was reported in the literature.

Although Anita Harding also described the association of neuromuscular manifestations in ADCA type I [21], neurophysiological studies in spinocerebellar disease are scarce. Linnemann and colleagues (2015) investigated 162 patients with SCA and found the higher frequencies of peripheral neuropathy in SCA 2 (92%) and neurophysiological changes in SCA1 (82%). Among 47 patients with SCA3, 55% presented electrophysiological defined neuropathy, classified in sensorimotor (69%), motor (23%), sensory (8%); the distribution of neuropathy by electrophysiological means showed axonal damage (27%) or axonal/demyelinating (mixed) (73%) [29]. Similar frequency was found among 55 SCA3 cases in Rio de Janeiro who underwent ENMG; 47% had neurophysiological changes indicative of polyneuropathy (sensory or sensorimotor) with axonal or myelin involvement.

In summary, Machado Joseph disease/SCA3 was the most frequent type of inherited dominant ataxia in RJ, followed by SCA7, SCA2, SCA6, SCA8, and SCA10 rare cases. The onset of the disease showed a wide range of variation; both genders were affected, and one-third of the cases were African descendants. Ataxia was associated, in different frequencies, with other neurological syndromes; few cases had a pure cerebellar syndrome. Severe disabilities occurred in the long term. Cerebellar atrophy and linear T2 hyperintensity along the medial margin of the globus pallidus were the most frequent brain MRI abnormalities. Early onset on SCA3 was associated with a larger number of CAG repeats and African ethnic background.

Change history

07 May 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-022-06117-5

References

Marsden JF (2018) Cerebellar ataxia. Handb Clin Neurol 159:261–281

Klockgether T (2010) Sporadic ataxia with adult onset: classification and diagnostic criteria. Lancet Neurol 9:94–104

van de Warrenburg BPC, van Gaalena J, Boeschb S, Burgunderc JM, Durr A, Giuntig P et al (2014) EFNS/ENS Consensus on the diagnosis and management of chronic ataxias in adulthood. Eur J Neurol 21:552–562

Hadjivassiliou M, Martindale J, Shanmugarajah P, Grünewald RA, Sarrigiannis PG, Beauchamp N et al (2017) Causes of progressive cerebellar ataxia: prospective evaluation of 1500 patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 88:301–309

de SILVA, et al (2019) Diagnosis and management of progressive ataxia in adults. Pract Neurol 2019(19):196–207

Orr HT, Chung MY, Banfi S, Kwiatkowski TJ Jr, Servadio A, Beaudet AL et al (1993) Expansion of an unstable trinucleotide CAG repeat in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Nat Genet 4:221–226

Mol MO, van Rooij JGJ, Brusse E, Verkerk AJMH, Melhem S, den Dunnen WFA et al (2020) Clinical and pathologic phenotype of a large family with heterozygous STUB1 mutation. Neurol Genet 23(6):e417

Sullivan R, Yau WY, O’Connor E, Houlden HJ (2019) Spinocerebellar ataxia: an update. Neurol 266:533–544

Ruano L, Melo C, Silva MC, Coutinho P (2014) The global epidemiology of hereditary ataxia and spastic paraplegia: a systematic review of prevalence studies. Neuroepidemiology 42:174–183

Teive HAG, Meira AT, Caramargo HF, Munhoz RP (2019) The geographic diversity of spinocerebellar ataxias (scas) in the Americas: a systematic review. Mov Disord Clin Pract 6(7):531–540

Jardim LB, Silveira I, Pereira ML, Ferro A, Alonso I, de Céu Moreira M et al (2001) A survey of spinocerebellar ataxia in South Brazil - 66 new cases with Machado-Joseph disease, SCA7, SCA8, or unidentified disease-causing mutations. Neurol. 248:870–6

Teive HA, Munhoz RP, Arruda WO, Lopes-Cendes I, Raskin S, Werneck LC et al (2012) Spinocerebellar ataxias: genotype-phenotype correlations in 104 Brazilian families. Clinics 67:443–449

de Castilhos RM, Furtado GV, Gheno TC, Schaeffer P, Russo A, Barsottini O et al (2014) Spinocerebellar ataxias in Brazil–frequencies and modulating effects of related genes. Cerebellum 13:17–28

Nascimento FA, Rodrigues VOR, Pelloso FC, Camargo CHF, Moro A, Raskin S et al (2019) Spinocerebellar ataxias in Southern Brazil: genotypic and phenotypic evaluation of 213 families. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 184:105427

Schmitz-Hosh T, Tezenas du Montcel S, Baliko L, Berciano J, Depondt Boesch S et al (2006) Scale for the assessment and rating of ataxia. Development of a new clinical scale. Neurology. 66:1717–1720

Braga-Neto P, Godeiro-Junior C, Dutra LA, Pedroso JL, Barsottini OGP (2010) Translation and validation into Brazilian version of the Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (SARA). Arq Neuropsiquiatr 68:228–230

Nakano KK, Dawson DM, Spence A (1972) Machado disease. A hereditary ataxia in Portuguese emigrants to Massachusetts. Neurology. 22:49–55

Coutinho P, Andrade C (1978) Autosomal dominant system degeneration in Portuguese families of the Azores Islands. A new genetic disorder involving cerebellar, pyramidal, extrapyramidal and spinal cord motor functions. Neurology. 28:703–9

Kawaguchi Y, Okamoto T, Taniwaki M, Aizawa M, Inoue M, Katayama S et al (1994) CAG expansions in a novel gene for Machado-Joseph disease at chromosome 14q32.1. Nat Genet. 8(3):221–8

Klockgether T, Mariotti C, Paulson HL (2019) Spinocerebellar ataxia. Nat Rev Dis Primers 5:24

Harding AE (1983) Classification of the hereditary ataxias and paraplegias. Lancet 1(8334):1151–1155

Matilla T, McCall A, Subramony SH, Zoghbi HY (1995) Molecular and clinical correlations in spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 and Machado-Joseph disease. Ann Neurol 38:68–72

Maciel P, Gaspar A, DeStefano AL, Silveira I, Coutinho P, Radvany J et al (1995) Correlation between CAG repeat length and clinical features in Machado-Joseph disease. Am J Hum Genet 57(1):54–61

Meira AT, Arruda WO, Ono SE, Carvalho Neto A, Raskin S, Camargo CHF et al (2019) Neuroradiological findings in the spinocerebellar ataxias. Tremor Hyperkinet Mov 26:9

Gelleren HM, Guo CC, O’Callaghan C, Tan RH, Sami S, Hornberger M (2017) Cerebellar atrophy in neurodegeneration-a meta-analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 88:780–788

Yamada S, Nishimiya J, Nakajima T, Taketazu F (2005) Linear high intensity area along the medial margin of the internal segment of the globus pallidus in Machado-Joseph disease patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 76:573–575

Shirai W, Ito S, Hattori T (2007) Linear T2 hyperintensity along the medial margin of the globus pallidus in patients with Mahado Joseph disease and Parkinson disease, and in healthy subjects. Am J Neuroradiol 28:1993–1995

Horimoto Y, Matsumoto M, Akatsu H, Kojima A, Yoshida M, Nokura K (2011) Longitudinal study on MRI intensity changes of Machado Joseph disease: correlation between MRI findings and neuropathological changes. J Neurol 258:1657–1664

Linnemann C, Montcel ST, Rakowicz M, Schmitz-Hübsch T, Szymanski S, Berciano J et al (2016) Peripheral neuropathy in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1, 2, 3, and 6. Cerebellum 15:165–173

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

The Research Ethics Committee of the institution approved this research involving human participants (CAAE29452620.0.0000.0022).

Consent to participate

Participants provided written informed consent prior to participation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: Originally, the article contains an error in Table 3. In the twentieth row/third column, "1" should be change to "-".

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Alvarenga, M.P., Siciliani, L.C., Carvalho, R.S. et al. Spinocerebellar ataxia in a cohort of patients from Rio de Janeiro. Neurol Sci 43, 4997–5005 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-022-06084-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-022-06084-x