Abstract

Background and purpose

Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) is a clinical and radiologic entity for which eclampsia is one of the most common predisposing conditions. Despite the imaging changes typically reported, the predisposing factors and clinical implications of atypical presentations have yet to be fully clarified.

Methods

A total of 56 patients with PRES were selected for study. Demographic, clinical, and laboratory data were analyzed, focusing on atypical presentations of PRES. Multiple logistic regression was applied to identify factors impacting such atypical presentations, and functional outcomes were assessed upon patient discharge.

Results

Overall, 22 of the 56 patients (39.3%) displayed features of atypical PRES. By multiple logistic regression, headache (OR = 5.39; 95% CI, 1.24–23.51; p = 0.025) and frequent convulsions (OR = 4.41; 95% CI, 1.09–17.91; p = 0.038) proved to be independent factors associated with atypical PRES. Ultimately, outcomes of 18 patients were gauged as poor, based on the modified Rankin Scale (mRS). Logistic regression indicated that visual disturbances (OR = 9.02; 95% CI, 1.37–59.35; p = 0.02), frequent convulsions (OR = 9.47; 95% CI, 1.67–53.63; p = 0.01), and restricted diffusion on imaging (OR = 11.96; 95% CI, 1.76–81.11; p = 0.01) were independently associated with poor outcomes in patients with eclampsia-related PRES.

Conclusion

Headache and frequent convulsions are independently associated with atypical presentations of PRES. If present, restricted diffusion may help in predicting poor outcomes of such patients upon discharge.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) is a clinical and radiologic entity first described by Hinchey et al. [1]. Patients may present with acute neurologic symptoms (i.e., impaired consciousness, visual disturbances, seizures, or headache) and focal neurologic signs [2]. Symmetric, bilateral vasogenic edema involving regions of occipital and parietal lobes is the most common finding by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [3].

Currently, there is no consensus on the pathophysiology of PRES, given the variety of suspected causes [4,5,6,7]. However, there are two widely accepted theories, one implicating dysregulation of cerebrovascular mechanisms, and the other alleging a vasculopathy. Neither of the theories has been fully corroborated under the pathophysiologic constraints of PRES [8]. Eclampsia is characterized by clinical hypertension, peripheral edema, proteinuria, and seizures during pregnancy and is one of the commonest conditions predisposing patients to PRES [9]. Past studies have speculated that endothelial dysfunction plays an important role in the development of PRES [10] and likely bears an association with eclampsia [10, 11]. Indeed, Liman et al. have documented a distinct correlation between PRES and eclampsia [12].

Atypical distributions including anterior cerebral lobes, brain stem, cerebellum, and basal ganglia and aberrant imaging defects, such as restricted diffusion, hemorrhage, and subarachnoid hemorrhage, have been attributed to PRES in recent studies [13,14,15,16], although they are usually reported in various primary diseases [17,18,19,20] and they are at odds with what is known about typical PRES. Whether they share common pathophysiologic mechanisms and clinical ramifications is not yet known. To determine factors associated with atypical presentations of PRES, we focused on a single etiology (i.e., eclampsia), examining patients whose course at our hospital resulted in fairly high morbidity. We also assessed the potential effects of atypical PRES on functional patient recovery.

Methods

Patients and study protocol

This study was a hospital-based retrospective investigation conducted at a single medical center between 2012 and 2016. All participants provided written informed consent prior to study enrollment. Each diagnosis of eclampsia adhered to criteria established by the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology [21]. Qualifying patients with eclampsia were subject to the following conditions: (1) acute or subacute onset of at least one neurologic symptom, such as severe headache, seizures, visual disturbances, or impaired consciousness; (2) MRI obtained within 48 h of symptom onset, revealing bilateral or unilateral focal edema of cortex and subcortical white matter; and (3) complete resolution of radiologic findings during pregnancy or postpartum [22].

Clinical parameters reviewed included patient age, blood pressure (BP), and gestational history. Data on neurologic symptoms, such as headache, visual disturbances, and convulsive frequencies, were also obtained. BP was recorded upon onset of neurologic symptoms, calculating mean blood pressure (MBP) as two thirds of diastolic blood pressure (DBP) and one third of systolic blood pressure (SBP). Frequent convulsions were defined as seizures in excess of three episodes. Routine laboratory diagnostics (platelet count, hemoglobin, d-dimer level, and serum creatinine) were retrieved as well.

Neuroimaging

MRI studies were conducted using an Achieva 3.0 Tesla scanner (Philips Healthcare, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), equipped with eight-channel phased array coil for brain imaging. The standard protocol consisted of axial T1- and T2-weighted sequences, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences, and diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI). Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps were calculated on a pixel-by-pixel basis. Mean ADC values for each region of interest were calculated automatically, and all follow-up MRI studies were performed during the course of hospitalization.

Patients were divided into typical and atypical presentation groups by MRI findings, specifically lesions identified on T2-weighted imaging and FLAIR, distributions of such lesions, extent of edema, evidence of restricted diffusion on DWI, and presence of intraparenchymal or subarachnoid hemorrhages. Two neuroimaging professors blinded to clinical data interpreted all MRI studies, reaching consensus decisions in event of any disagreement. In this study, extensive edema corresponded with involvement of more than five anatomic areas of the brain [23].

High DWI signals in conjunction with decreased ADC were indicative of restricted diffusion (cytotoxic edema), whereas low DWI signals with increased ADC indicated vasogenic edema [24, 25]. Involvement of anterior the cerebral lobes, brain stem, cerebellum, and basal ganglia or lesions demonstrating restricted diffusion on DWI constituted atypical presentations in this study [26, 27].

Treatment and outcomes

The primary treatment was to monitor and control any sudden increase in BP in patients with SBPs ≥ 160 mmHg, DBPs ≥ 110 mmHg, or MBPs ≥ 140 mmHg who received intravenous labetalol treatment. As seizure prophylaxis, we administered 25% magnesium sulfate solution (20 ml) diluted in 10% glucose solution by intravenous route (5–10 min) to all patients. Sudden-onset seizures were controlled by diazepam (10 mg).

Clinical outcomes were scored at time of patient discharge using a modified Rankin Scale (mRS), applied by a neurologist with mRS expertise. Assigned mRS scores of 0–2 were considered good outcomes in terms of functional independence, whereas scores of 3–6 signaled poor outcomes [28].

Statistical methods

All statistical computations relied on standard software (SPSS v17.0, SPSS Inc. (IBM), Chicago, IL, USA), setting statistical significance at p < 0.05. Continuous variables were each expressed as mean ± SD, reporting discrete data as frequencies and percentages. Student’s t test was applied for continuous variables, and for discrete variables, Fisher’s exact test was used. In multivariate analysis, a forward stepwise variable selection method was invoked to calculate odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for factors related to atypical presentations of PRES and predictive of PRES outcomes at discharge in patients with eclampsia.

Results

Clinical characterizations

A total of 141 obstetric patients diagnosed with eclampsia underwent MRI scans of the brain within 48 h of neurologic symptom onset. However, only 56 patients (mean age 28.3 ± 5.8 years) qualified for the study, having excluded 66 patients with normal radiologic diagnoses, one with cerebral hemorrhage, one with subarachnoid hemorrhage, and 17 with inadequate clinical records.

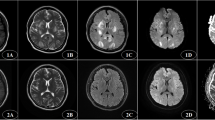

The spectrum of neurologic symptoms included headache (30/56, 53.6%), frequent convulsions (22/56, 39.3%), and visual disturbances (18/56; 32.1%). When analyzing lesion distributions, we found that parietal and occipitoparietal lobes were the most commonly involved regions (89.3% and 71.4%, respectively) (Fig. 1), although in atypical presentations of PRES, the basal ganglia (60.7%) and cerebellum (19.6%) (Fig. 2) prevailed. In Fig. 3, bilateral occipital vasogenic edema and a right occipital zone of restricted diffusion are depicted.

A 31-year-old woman with sudden blood pressure surge, complaining of blurred vision and headache for 10 h: a axial T2-weighted image of lesions in typical bilateral occipital distribution; b axial DWI imaging showing bilateral occipital hypointensities, with right occipital zone of restricted diffusion; and c complete resolution of bilateral occipital lesions in repeat axial T2-weighted image (mRS score of 3 at discharge)

Factors linked to atypical presentations of PRES in patients with eclampsia

A total of 22 patients were assigned to the atypical presentation group. In comparing clinical and laboratory data of both groups with PRES (typical and atypical), headache (p = 0.004), visual disturbances (p = 0.021), and frequent convulsions (p < 0.001) were more common in the atypical group, and DBP was higher (Table 1). In logistic regression analysis, headache (OR= 5.39; 95% CI, 1.24–23.51; p = 0.025) and frequent convulsions (OR = 4.41; 95% CI, 1.09–17.91; p = 0.038) emerged as variables independently associated with atypical presentation of PRES in patients with eclampsia (Table 2).

Factors associated with clinical outcomes at time of discharge

Poor functional outcomes (i.e., mRS scores of 3–6) were evident in 18 patients (32.1%). The remaining 38 patients had good functional outcomes at discharge (Table 3). We stratified patients by mRS scores to compare outcomes (poor vs good) at discharge, finding that these subsets differed in incidences of visual disturbances (p = 0.01), convulsive frequencies (p < 0.001), and restricted diffusion (p = 0.002). A greater incidence of occipital involvement and higher platelet counts were observed in the poor (vs good) outcome group (Table 4). In logistic regression analysis, visual disturbances (OR = 9.02; 95% CI, 1.37–59.35; p = 0.02), frequent convulsions (OR = 9.47; 95% CI, 1.67–53.63; p = 0.01), and restricted diffusion (OR = 11.96; 95% CI, 1.76–81.11; p = 0.01) showed independent associations with poor outcomes of PRES in patients with eclampsia at discharge (Table 5).

Discussion

PRES is one of the most common neurologic complications in patients with eclampsia. However, acute intermittent porphyria, intravenous cyclophosphamide therapy, post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis, and hematologic malignancies may similarly predispose to PRES [29,30,31]. Given the variety of conditions implicated, the precise pathogenesis of PRES remains controversial. Aleksandra et al. have noted that the capacity to autoregulate BP in the cerebral vasculature declines or is completely attenuated during pregnancy. Thus, if severe endothelial injury occurs (as in instances of eclampsia), even a moderate increase in BP may lead to neurologic complications [27, 32]. Consequently, the endothelial injury sustained during eclampsia is an important potential contributor to PRES [33], with endothelial dysfunction exerting more influence than hypertension in this setting.

Typically, PRES presents as bilateral, symmetric vasogenic edema, predominantly involving the subcortical white matter of occipital and parietal lobes, and it is usually reversible [8]. However, atypical patterns of PRES have been increasingly recognized [26, 34, 35], showing lesions of the deep white matter, basal ganglia, brainstem, and the splenium of the corpus callosum (otherwise rarely seen). Rare imaging findings are also present, such as a restricted diffusion, hemorrhage, and subarachnoid hemorrhage. These features have led many researchers to speculate on predisposing factors and clinical implications in atypical presentations of PRES. For the present study, we selected patients with eclampsia and PRES showing relatively high morbidity in our hospital, focusing on a single etiology to facilitate comparisons made. We subsequently found that the occurrence rate of headache was much higher in the atypical presentation group and was independently related to atypical imaging findings. Hence, it may be that BP (SBP, DBP, and MBP) in the atypical group exceeded that of the typical group, encouraging cerebrovascular autoregulatory disorders and leading to headaches. Alternatively, we found that in patients with atypical (vs typical) PRES, intracranial lesions were more widespread, and enlarging, swollen areas are more apt to cause headaches [17]. Another independent factor in atypical presentations was frequent convulsions. In patients with eclampsia, frequent seizures usually imply more severe vascular endothelial damage and increased vascular permeability, accentuating edema of the brain edema. This may further explain the development of atypical presentations [36].

Hemorrhage or subarachnoid hemorrhage is becoming more widely recognized as an atypical manifestation of PRES [37]. Unfortunately, clinical imaging data for the one patient with intracerebral hemorrhage and the other with subarachnoid hemorrhage were incomplete, prompting their exclusion from this study.

Upon early diagnosis and treatment of the underlying cause, the prognosis of PRES is usually satisfactory. In our study, 18 patients received poor prognostic mRS scores at time of discharge, most showing moderate disability. In logistic regression analysis of factors impacting patient prognosis, we found that visual disturbances, restricted diffusion, and frequent convulsions were independently linked to the short-term prognosis of patients with PRES. The visual disturbances typically manifested are blurred vision, homonymous hemianopsia, and cortical blindness, which were more likely experienced by those in our cohort with poor outcomes. Both occipital and parietal lobes (as visual centers) are most often affected, but there are visual conductive fibers also at risk within subcortical white matter and the basal ganglia. A broader distribution of lesions increases the likelihood of visual symptoms, thus contributing to poor prognoses. Restricted diffusion is the second most frequent feature encountered in atypical presentations of PRES [5]. Although the reversibility of cytotoxic edema remains controversial, our previous studies in this regard have demonstrated that cytotoxic edema is a reversible event in patients with preeclampsia or eclampsia.

Data from various studies have supported the role of restricted diffusion in predicting the development of infarctions by some patients [27]. However, we found that cytotoxic edema (by DWI criteria) is usually accompanied by vasogenic edema, and as vasogenic edema resolves, cytotoxic edema simultaneously eases. This transient cytotoxic edema is not the same as that incited by acute cerebral infarction. In our view, restricted diffusion is a consequence of severe edema or heightened vascular permeability due to endothelial damage, heralding poor prognostic outlooks for such patients. Severe vascular endothelial injury, inducing convulsions or increasing their frequency and causing secondary brain edema and cerebral ischemia/hypoxia, is also likely to result in a poor prognosis [10]. Furthermore, our patients with poor outcomes had comparatively higher platelet counts. Arterial endothelial injury may promote platelet aggregation, increasing the number of circulating platelets, which then reflects the degree of vascular endothelial injury [38] and provides an additional prognostic index.

In patients with eclampsia, the recommended treatment of PRES generally includes delivery of the baby and placenta as soon as possible, antihypertensive drug therapy to manage arterial hypertension, use of magnesium sulfate as prophylaxis of eclamptic convulsions, and phenytoin or diazepam administration for rapid control of convulsions that may ensue [39, 40].

In the present study, we had a singular objective, namely the study of eclampsia-induced PRES. We also focused on a single etiology for comparative purposes, hoping to eliminate bias in part. Nonetheless, there are several acknowledged limitations. First, this was a single-center retrospective review, and the number of patients was relatively small. Second, due to the brief window for prognostication (i.e., time of discharge), the long-term ramifications of PRES in patients with eclampsia could not be determined.

Conclusions

Atypical radiologic findings should not exclude PRES as a possible diagnosis if the appropriate clinical presentation exists. In patients with eclampsia, headache and frequent convulsions may be independently related to atypical presentations of PRES. When assessing the short-term prognoses of such patients, we found that visual disturbances, restricted diffusion (on DWI), and frequent convulsions may help identify patients at a greater risk of poor outcomes.

References

Hinchey J, Chaves C, Appignani B, Breen J, Pao L, Wang A, Pessin MS, Lamy C, Mas JL, Caplan LR (1996) A reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome. N Engl J Med 334(8):494–500. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199602223340803

Fugate JE, Rabistein AA (2015) Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: clinical and radiological manifestations, pathophysiology, and outstanding questions. Lancet Neurol 14(9):914-925

Bartynski WS, Boardman JF (2007) Distinct imaging patterns and lesion distribution in posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. Am J Neuroradiol 28(7):1320–1327. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A0549

Chen Z, Xu M, Shang D, Luo B (2012) A case of reversible splenial lesions in late postpartum preeclampsia. Intern Med 51(7):787–790. https://doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.51.6500

Benziada-Boudour A, Schmitt E, Kremer S, Foscolo S, Riviere AS, Tisserand M, Boudour A, Bracard S (2009) Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: a case of unusual diffusion-weighted MR images. J Neuroradiol 36(2):102–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurad.2008.08.003

Ishikura K, Hamasaki Y, Sakai T, Hataya H, Goto T, Miyama S, Kono T, Honda M (2011) Children with posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome associated with atypical diffusion-weighted imaging and apparent diffusion coefficient. Clin Exp Nephrol 15(2):275–280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10157-010-0380-2

Pande AR, Ando K, Ishikura R, Nagami Y, Takada Y, Wada A, Watanabe Y, Miki Y, Uchino A, Nakao N (2006) Clinicoradiological factors influencing the reversibility of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: a multicenter study. Radiat Med 24(10):659–668. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11604-006-0086-2

Li Y, Gor D, Walicki D, Jenny D, Jones D, Barbour P, Castaldo J (2012) Spectrum and potential pathogenesis of reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 21(8):873–882. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2011.05.010

Wagner SJ, Acquah LA, Lindell EP, Craici IM, Wingo MT, Rose CH, White WM, August P, Garovic VD (2011) Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome and eclampsia: pressing the case for more aggressive blood pressure control. Mayo Clin Proc 86(9):851–856. https://doi.org/10.4065/mcp.2011.0090

Bartynski WS (2008) Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, part 2: controversies surrounding pathophysiology of vasogenic edema. Am J Neuroradiol 29(6):1043–1049. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A0929

Hod T, Cerdeira AS, Karumanchi SA (2015) Molecular mechanisms of preeclampsia. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 5(10). https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a023473

Liman TG, Bohner G, Heuschmann PU, Scheel M, Endres M, Siebert E (2012) Clinical and radiological differences in posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome between patients with preeclampsia-eclampsia and other predisposing diseases. Eur J Neurol 19(7):935–943. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03629.x

Karampekios SK, Contopoulou E, Basta M, Tzagournissakis M, Gourtsoyiannis N (2004) Hypertensive encephalopathy with predominant brain stem involvement: MRI findings. J Hum Hypertens 18(2):133–134. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jhh.1001654

Chen TY, Lee HJ, Wu TC, Tsui YK (2009) MR imaging findings of medulla oblongata involvement in posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome secondary to hypertension. Am J Neuroradiol 30(4):755–757. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A1337

Ekawa Y, Shiota M, Tobiume T, Shimaoka M, Tsuritani M, Kotani Y, Mizuno Y, Hoshiai H (2012) Reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome accompanying eclampsia: correct diagnosis using preoperative MRI. Tohoku J Exp Med 226(1):55–58. https://doi.org/10.1620/tjem.226.55

Tari Capone F, Candela S, Bozzao A, Orzi F (2015) A new case of brainstem variant of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: clinical and radiological features. Neurol Sci 36(7):1263–1265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-014-1999-7

Hinduja A, Habetz K, Raina S, Ramakrishnaiah R, Fitzgerald RT (2017) Predictors of poor outcome in patients with posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. Int J Neurosci 127(2):135–144. https://doi.org/10.3109/00207454.2016.1152966

Golombeck SK, Wessig C, Monoranu C-M, Schutz A, Solymosi L, Melzer N, Kleinschnitz C (2013) Fatal atypical reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome: a case report. J Med Case Rep 7:14–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1947-7-14

O'Kane M, Elhalwagy H, Kumar S, Badawi C (2014) Unusual presentation of PRES in the postnatal period. BMJ Case Rep. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2013-203406

Li Q, Lv F, Wei Y, Yan B, Xie P (2013) Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus after cessation of oral prednisone. Neurol Sci 34(12):2241–2242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-013-1479-5

American College of O, Gynecologists, Task Force on Hypertension in P (2013) Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 122(5):1122–1131. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.aog.0000437382.03963.88

Porcello Marrone LC, Marrone BF, Gadonski G, Huf Marrone AC, da Costa JC (2012) Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol 10(9):614–615

Schweitzer AD, Parikh NS, Askin G, Nemade A, Lyo J, Karimi S, Knobel A, Navi BB, Young RJ, Gupta A (2017) Imaging characteristics associated with clinical outcomes in posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. Neuroradiology 59(4):379–386. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00234-017-1815-1

Singh RR, Ozyilmaz N, Waller S, U-King-Im J-M, Lim M, Siddiqui A, Sinha MD (2014) A study on clinical and radiological features and outcome in patients with posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES). Eur J Pediatr 173(9):1225–1231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-014-2301-y

Provenzale JM, Petrella JR, Cruz LCH, Wong JC, Engelter S, Barboriak DP (2001) Quantitative assessment of diffusion abnormalities in posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. Am J Neuroradiol 22(8):1455–1461

McKinney AM, Short J, Truwit CL, McKinney ZJ, Kozak OS, SantaCruz KS, Teksam M (2007) Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: incidence of atypical regions of involvement and imaging findings. Am J Roentgenol 189(4):904–912. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.07.2024

Aracki-Trenkic A, Stojanov D, Trenkic M, Radovanovic Z, Ignjatovic J, Ristic S, Trenkic-Bozinovic M (2016) Atypical presentation of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: clinical and radiological characteristics in eclamptic patients. Bosn J Basic Med Sci 16(3):180–186. https://doi.org/10.17305/bjbms.2016.1201

Bloch RF (1988) Interobserver agreement for the assessment of handicap in stroke patients. Stroke 19(11):1448–1448

Tavares M, Arantes M, Chacim S, Campos Junior A, Pinto A, Mariz JM, Sonin T, Pereira S (2015) Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in children with hematologic malignancies. J Child Neurol 30(12):1669–1675. https://doi.org/10.1177/0883073815578525

Alp A, Akdam H, Akar H, Koseoglu K, Ozkul A, Meteoglu I, Yenicerioglu Y (2014) Polyarteritis nodosa complicated by posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: a case report. Nefrologia 34(6):789–796. https://doi.org/10.3265/Nefrologia.pre2014.Sep.12510

Zhao B, Wei Q, Wang Y, Chen Y, Shang H (2014) Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in acute intermittent porphyria. Pediatr Neurol 51(3):457–460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2014.05.016

Lin JT, Wang SJ, Fuh JL, Hsiao LT, Lirng JF, Chen PM (2003) Prolonged reversible vasospasm in cyclosporin A-induced encephalopathy. Am J Neuroradiol 24(1):102–104

Rykken JB, McKinney AM (2014) Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. Seminars In Ultrasound Ct And Mri 35(2):118–135. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.sult.2013.09.007

Donmez FY, Basaran C, Ulu EMK, Yildirim M, Coskun M (2010) MRI features of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in 33 patients. J Neuroimaging 20(1):22–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-6569.2008.00306.x

Kastrup O, Schlamann M, Moenninghoff C, Forsting M, Goericke S (2015) Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: the spectrum of MR imaging patterns. Clin Neuroradiol 25(2):161–171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00062-014-0293-7

Bartynski WS, Boardman JF (2008) Catheter angiography, MR angiography, and MR perfusion in posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. Am J Neuroradiol 29(3):447–455. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A0839

Stevens CJ, Heran MKS (2012) The many faces of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. Br J Radiol 85(1020):1566–1575. https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr/25273221

de Groot PG, Urbanus RT, Roest M (2012) Platelet interaction with the vessel wall. Handb Exp Pharmacol 210:87–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-29423-5_4

Shankar J, Banfield J (2017) Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: a review. Can Assoc Radiol J 68(2):147–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carj.2016.08.005

Sibai BM (2005) Diagnosis, prevention, and management of eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol 105(2):402–410. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.aog.0000152351.13671.99

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards

This study conformed to Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects endorsed by the Chinese government and was authorized by the Ethics Committee of Shengjing Hospital at China Medical University.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dong, X., Nao, J. Influential factors and clinical significance of an atypical presentation of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in patients with eclampsia. Neurol Sci 40, 377–384 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-018-3642-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-018-3642-5