Abstract

Ramadan, the ninth month of the Muslim lunar calendar, is a period of intermittent fasting alternated with moments of refeeding. The last decades have seen a growing number of reports that examine the potential effect of Ramadan intermittent fasting (RIF) on chronic musculoskeletal disorders. In this paper, we reviewed data that assessed the relationship of intermittent diurnal fasting during Ramadan with rheumatic diseases. Currently, recent evidence indicates that RIF may attenuate the inflammatory state by suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokine expression and reducing the body fat and the circulating levels of leukocytes. Therefore, it may be a promising non-pharmacological approach for managing the course of rheumatic inflammatory diseases. Despite differences between studies in daily fasting duration and dietary norms, there appears to be a consensus that most of the patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) or spondyloarthritis (SpA) who fasted Ramadan experienced relief of their symptoms. Nevertheless, further clinical trials are required to assess the effect of RIF on other musculoskeletal and bone disorders. Additionally, we evaluated the impact of RIF on chronic medication intake. Even if a few studies on this issue are available, the primary outcomes indicate that RIF does not significantly impair either compliance or tolerance to chronic medications. These findings may give some reassurance to patients with a specific fear of drug intake during this month.

Key Points • Intermittent diurnal fasting during Ramadan can modulate the inflammatory status through the down-regulation of metabolic syndrome, the reduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and the reduction of circulating levels of leukocytes • Ramadan intermittent fasting (RIF) can effectively improve the activity of rheumatic inflammatory diseases. • Although further studies are still required, there seems no harm for patients with gout to participate in RIF. • Primary outcomes indicate that RIF may be a promising non-pharmacological intervention for the management of patients with osteoarthritis and osteoporosis. |

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Fasting for spiritual purposes and during special periods is a characteristic of major religions of the world. Various fasting rituals are differing from one religion to another. Ramadan, the ninth month of the Muslim lunar calendar, is a period of intermittent fasting alternated with moments of refeeding. During this month, approximately 1.5 billion Muslims all over the world abstain from food, drink, smoking, and sex from dawn until sunset [1]. They consume two meals per day, one large meal after sunset (Iftar), and one lighter meal before dawn (Suhur) [2]. Individuals to whom fasting may be harmful are exempted [3]. Since this month rotates during the Gregorian calendar, the range of fasting hours varies according to the season and the location’s latitudinal distance from the equator [2]. In fact, the length of daytime on any date varies according to the latitude. Therefore, the length of fasting hours is longer during summer, and this pattern is more pronounced in countries that are north of the equator.

In addition to its spiritual role, Ramadan intermittent fasting (RIF) has been suggested as a potential non-pharmacological intervention for improving the course of chronic diseases [2]. Indeed, many patients believe that RIF influences their disease activity and report either an improvement or a worsening of their symptoms during this month [4].

In the last two decades, a growing number of studies have examined the potential effect of RIF on chronic inflammatory diseases and musculoskeletal disorders.

Patients with chronic rheumatic conditions may consult their physicians and seek advice on the safety of RIF and its potential impact. Given the lack of standardized recommendations on this topic and the need for additional data to address patient concerns, our purposes were to evaluate the possible effects of RIF on rheumatic inflammatory, degenerative, and metabolic diseases and to suggest new perspectives for research. However, it is worth noting that we did not include other autoimmune and connective tissue diseases because of the lack of investigations in this field.

Search strategy

We performed a literature review of PubMed and Google Scholar databases using the following sets of keywords: (i) “Ramadan fasting,” “Intermittent fasting,” and “Islamic fasting” and (ii) “Rheumatic disease,” “Rheumatoid arthritis,” “Spondyloarthritis,” “Ankylosing spondylitis,” “Psoriatic arthritis,” “Gout,” “Chondrocalcinosis,” “Osteoarthritis,” and “Osteoporosis.” Studies, published up to April 2020, including patients with rheumatic diseases who fasted all or part of Ramadan, were eligible. All types of study designs restricted to humans were included. Articles not in English or French and with no translation were excluded.

Impact of RIF on rheumatic inflammatory status

The positive impact of RIF on the inflammatory status has been demonstrated in both healthy individuals [5,6,7] and patients with chronic inflammatory disorders [8, 9].

Firstly, a significant decrease of CRP, interleukin (IL)-6, IL-1β, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha has been reported during and after Ramadan [10, 11].

In addition to suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokine expression, attenuation of inflammatory state can be explained by the reduction of body fat and the control of metabolic risk factors [10]. Restricting feeding to a limited duration of the day is expected to result in reduced energy intake and weight loss. However, the effect of RIF on the dietary pattern and the daily intake of calories varies depending on other influencing factors such as age, gender, ethnicity, lifestyle, and eating habits [1]. The feasting period can be an opportunity to consume different kinds and a large amount of foods and drinks. In this context, a considerable number of studies, with mixed results, evaluated the effect of RIF on body weight and lipid profile. A meta-analysis, carried out in 2014 by Kul et al., included 30 studies and demonstrated that RIF can significantly reduce total body weight, total cholesterol, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDLC) levels compared with the pre-Ramadan period [1]. This reduction, contrasting with the reported insignificant changes in total energy intake, was partly explained by the efficient utilization of body fat during Ramadan [1, 12]. A more recent systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by Faris et al. in 2019 assessed the impact of RIF on metabolic syndrome features [13]. Data extracted from 85 studies conducted in 23 countries demonstrated that RIF induced small but significant reductions in waist circumference, fasting blood glucose level, systolic blood pressure, and triglyceride level, with a concomitant small increase in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDLC) [13].

An additional proven anti-inflammatory effect of RIF is the significant decrease in circulating levels of leukocytes [10]. However, despite the reduction of total leukocytes, lymphocytes, monocytes, and granulocytes noted during Ramadan, the values remained in the reference ranges [10].

Furthermore, RIF has been found to affect intestinal microbiota composition [5, 6]. A significant increase in A. muciniphila and B. fragilis group, considered healthy gut microbiota members, has been reported after fasting 29 days of Ramadan [5].

Given the above positive effects on the immune and inflammatory status (Fig. 1), it was hypothesized that RIF has an impact on rheumatic diseases. This potential impact of RIF has recently been the subject of scientific inquiry, with most of the research being performed in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Several investigations explored the relationship of the metabolic syndrome with the chronic inflammatory status and concluded to a close link between these entities [14, 15]. For example, the negative impact of overweight or obesity on RA disease activity has been demonstrated by previous reports, with a higher degree of synovitis and reduced odds of achieving remission [16, 17]. Thus, it was deemed that intermittent fasting may be a promising approach to manipulate the inflammatory process through the down-regulation of metabolic syndrome. On another note, the imbalance between useful and harmful bacteria in gut microbiota may contribute to the occurrence and the activity of inflammatory rheumatic diseases [14, 18]. Therefore, the induced changes of gut microbiota during Ramadan could attenuate and restore the alterations of the gut microbiomes in individuals with rheumatic diseases [19].

Impact of RIF on rheumatoid arthritis

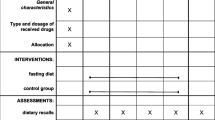

Previous studies that assessed the impact of RIF on RA activity were conducted in Irak, Malaysia, Iran, and Tunisia [8, 20,21,22]. As shown in Table 1, the number of fasting hours ranged from 11.5 to 16.5. Despite the differences between studies in daily fasting duration, dietary norms, and nutritional habits, there appears to be a consensus that most of the patients who fasted Ramadan experienced a relief of symptoms related to RA. RIF was shown to induce a significant decrease of morning stiffness [20, 22], pain assessed by visual analog scale (VAS) [8, 21], and tender and swollen joint count [8, 21, 22]. Regarding inflammatory markers, two studies have reported a significant reduction of CRP and/or ESR [8, 21], whereas two others showed no significant changes in these variables [20, 22]. These divergent results may be explained by differences in the follow-up period, the timing of evaluation, ethnicity, dietary intake, lifestyle, and cultural habits. Collectively, the majority of findings indicates an improvement in disease activity scores (DAS28) in patients fasting Ramadan. Therefore, intermittent fasting could be helpful for the management of patients with active RA. The minimal required duration and the sustainability of the positive impact of fasting need to be determined in further investigations.

On a separate note, it is worth mentioning that other fasting protocols have also been assessed. For example, partial continuous fasting followed by a vegetarian diet has been shown to induce subjective and objective improvements in RA, though of short duration [23,24,25].

Impact of RIF on spondyloarthritis

In a Tunisian study including 20 patients with spondyloarthritis (SpA), Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score ESR (ASDASESR) decreased significantly after RIF, whereas there was no significant change in the level of Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) and ASDASCRP [8]. In another study including 37 patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA), RIF was shown to reduce Disease Activity Index for Psoriatic Arthritis (DAPSA), BASDAI, Leeds Enthesitis Index (LEI), and Dactylitis Severity Score (DSS) [9]. However, the non availability of a control group may preclude generalization of these results. Additional studies with larger sample sizes and control groups are needed to confirm or refute the positive impact of RIF on SpA activity.

Impact of RIF on gout

During Ramadan, Muslims enjoy a feasting atmosphere at sunset and can consume different kinds of foods freely. Also, the improvement in the standards of living over the years may lead to several changes in eating habits, such as consumption of large quantities of meat and fats. Therefore, Ramadan fast could be a potential risk factor for the increase of serum uric acid levels. This statement has been confirmed by several studies that included either healthy people or patients with diabetes [26,27,28]. However, this risk has not been demonstrated in patients with gout. Habib et al. compared mean serum uric acid levels of two groups of patients (fasting group and non-fasting group) just prior and at the end of Ramadan and did not find a significant change [29]. Additionally, there was no significant difference in arthritis or renal calculi attacks between the two groups and also within each group during Ramadan compared with baseline [29]. Based on these results, there seems no harm for patients with gout to participate in RIF. However, considering the lack of randomized controlled trials, few definitive conclusions can currently be made on this topic. Future studies should focus on other metabolic rheumatic diseases.

Impact of RIF on osteoarthritis

There is still a lack of information regarding the effect of RIF on osteoarthritis (OA). However, given the pro-inflammatory mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of OA [30], the positive effects of RIF on the inflammatory process may be transposed to patients with OA.

A questionnaire-based survey conducted in a Muslim-majority area of India revealed that 49.3% of patients with OA believe that RIF improves the major symptoms (pain, swelling, range of motion) [4]. Conversely, 4% of patients experienced an aggravation of symptoms during Ramadan [4]. Few conclusions can currently be made regarding the impact of RIF on degenerative conditions. Further studies are needed to focus on this area.

Impact of RIF on osteoporosis

As RIF has been found to have a beneficial effect on the secretion of parathyroid hormone (PTH) [31], it was hypothesized that it could positively affect bone metabolism. A further potential positive impact of RIF is the activation of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors [32]. In fact, the DPP-4 gene has been identified as an important genetic factor contributing to the progression of osteoporosis [32]. Further investigations should examine the possible effects of RIF on bone disorders such as osteoporosis.

Studies limitations

Confounding variables that can influence the effect of RIF include variability in daily fasting time, smoking status, chronic medications, dietary intake, physical activity, and cultural habits [2]. Although most manuscripts reported the daily number of fasting hours, the other confounding variables were not always reported. Except for one study [20], detailed data related to nutrient and calorie intakes were not documented. Since smoking is forbidden during the daylight hours, reducing the number of cigarettes may contribute to improve the symptoms. However, the smoking status was examined as a potential confounding factor only in 2 reports [8, 9]. Future studies should minimize or even eliminate the effect of such confounding variables.

Additionally, another important point should be taken into account when assessing the effect of RIF. Given the long duration of this type of fast (1 month), a physiological adaptation can be progressively established. Therefore, the physiological changes of the first week of the month may differ from those occurring at the end of the month [33].

Finally, the main limitation of the studies included in this review is the relatively limited number of participants. Larger sample sizes in further studies would increase the power of the statistical findings.

Medication therapy during Ramadan

There are a limited number of reports about medication intake during Ramadan. In this context, three major issues arise: the adherence of patients to chronic medications, the tolerability, and the timing of drug intake. Since Muslims consume two major meals during Ramadan, compliance with medications that are taken once or twice a day should not be impaired. Despite some mixed results, the general opinion is that RIF does not significantly impair either compliance or tolerance to chronic medications [8, 29]. Regarding patients with gout, RIF did not hamper either allopurinol’s or colchicine’s adherence [29]. Furthermore, there was no significant change in the level of adherence to the low-purine diet during Ramadan [29]. The situation may be more delicate for patients with inflammatory chronic diseases, probably because of polypharmacy and/or the common gastrointestinal side effects related to some medications. Among 56 patients with RA or SpA who fasted Ramadan 2019, adherence to methotrexate was impaired in 30% of the patients, and the consumption of NSAIDs was reduced in 25% of patients [8]. The main reported reasons for discontinuation were the short duration between Iftar and Suhur (7.5–8.5 h) and the apprehension of gastrointestinal adverse effects. Nevertheless, compliance with biological agents, sulfasalazine, leflunomide, and corticosteroids was similar before and during fasting.

Alomi and coworkers have recently published the first suggestion draft of switch drug therapy from regular days to Ramadan days [34]. The suggested table may help the prescriber to adapt the timing of drug intake and the dosage to the lifestyle of Ramadan. Among the 171 drugs included in this research, six are commonly prescribed by rheumatologists (celecoxib, diclofenac, leflunomide, meloxicam, naproxen, piroxicam). No major adaptations have been recommended for these classes of medications. However, this approach needs to be validated by further randomized clinical trials. RIF effects in the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of DMARDs, corticosteroids, NSAIDs, and analgesics should be evaluated by future studies.

Conclusions

Diurnal intermittent fasting during Ramadan has been shown to have positive effects on rheumatic inflammatory diseases. The potential impact of RIF on metabolic and degenerative conditions is still understudied. Despite some heterogeneous findings, we can conclude that RIF does not significantly impair either compliance or tolerance to chronic medications.

To sum up, RIF seems to be a promising non-pharmacological approach that deserves complementary studies. Further investigations should focus on the sustainability of the positive effects and the minimum required duration of fasting.

References

Kul S, Savaş E, Öztürk ZA, Karadağ G (2014) Does Ramadan fasting alter body weight and blood lipids and fasting blood glucose in a healthy population? A meta-analysis. J Relig Health 53:929–942. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-013-9687-0

Trepanowski JF, Bloomer RJ (2010) The impact of religious fasting on human health. Nutr J 9:57. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-9-57

Rouhani MH, Azadbakht L (2014) Is Ramadan fasting related to health outcomes? A review on the related evidence. J Res Med Sci Off J Isfahan Univ Med Sci 19:987–992

Munshi Y, Iqbal M, Rafique H et al (2008) Role of diet in disease activity of arthritis-a questionnaire based survey. Pak J Nutr 7:137–140

Ebrahimi S, Rahmani F, Avan A et al (2016) Effects of Ramadan fasting on the regulation of inflammation. J Fasting Health 4:32–37

Aksungar FB, Topkaya AE, Akyildiz M (2007) Interleukin-6, C-reactive protein and biochemical parameters during prolonged intermittent fasting. Ann Nutr Metab 51:88–95. https://doi.org/10.1159/000100954

Adawi M, Watad A, Brown S, Aazza K, Aazza H, Zouhir M, Sharif K, Ghanayem K, Farah R, Mahagna H, Fiordoro S, Sukkar SG, Bragazzi NL, Mahroum N (2017) Ramadan fasting exerts immunomodulatory effects: insights from a systematic review. Front Immunol 8:1144. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2017.01144

Ben Nessib D, Maatallah K, Ferjani H, Kaffel D, Hamdi W (2020) Impact of Ramadan diurnal intermittent fasting on rheumatic diseases. Clin Rheumatol 39:2433–2440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-020-05007-5

Adawi M, Damiani G, Bragazzi NL, Bridgewood C, Pacifico A, Conic R, Morrone A, Malagoli P, Pigatto P, Amital H, McGonagle D, Watad A (2019) The impact of intermittent fasting (Ramadan fasting) on psoriatic arthritis disease activity, enthesitis, and dactylitis: a multicentre study. Nutrients 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11030601

Faris MA-IE, Kacimi S, Al-Kurd RA et al (2012) Intermittent fasting during Ramadan attenuates proinflammatory cytokines and immune cells in healthy subjects. Nutr Res N Y N 32:947–955. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nutres.2012.06.021

Ajabnoor GMA, Bahijri S, Shaik NA, Borai A, Alamoudi AA, al-Aama JY, Chrousos GP (2017) Ramadan fasting in Saudi Arabia is associated with altered expression of CLOCK, DUSP and IL-1alpha genes, as well as changes in cardiometabolic risk factors. PLoS One 12:e0174342. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0174342

El Ati J, Beji C, Danguir J (1995) Increased fat oxidation during Ramadan fasting in healthy women: an adaptative mechanism for body-weight maintenance. Am J Clin Nutr 62:302–307. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/62.2.302

Faris MA-IE, Jahrami HA, Alsibai J, Obaideen AA (2020) Impact of Ramadan diurnal intermittent fasting on metabolic syndrome components in healthy, non-athletic Muslim people aged over 15 years: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Nutr 123:1–22. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000711451900254X

Medina G, Vera-Lastra O, Peralta-Amaro AL, Jiménez-Arellano MP, Saavedra MA, Cruz-Domínguez MP, Jara LJ (2018) Metabolic syndrome, autoimmunity and rheumatic diseases. Pharmacol Res 133:277–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2018.01.009

Francisco V, Ruiz-Fernández C, Pino J, Mera A, González-Gay MA, Gómez R, Lago F, Mobasheri A, Gualillo O (2019) Adipokines: linking metabolic syndrome, the immune system, and arthritic diseases. Biochem Pharmacol 165:196–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2019.03.030

Liu Y, Hazlewood GS, Kaplan GG, Eksteen B, Barnabe C (2017) Impact of obesity on remission and disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res 69:157–165. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.22932

Alivernini S, Tolusso B, Gigante MR, Petricca L, Bui L, Fedele AL, di Mario C, Benvenuto R, Federico F, Ferraccioli G, Gremese E (2019) Overweight/obesity affects histological features and inflammatory gene signature of synovial membrane of rheumatoid arthritis. Sci Rep 9:10420. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-46927-w

Guerreiro CS, Calado Â, Sousa J, Fonseca JE (2018) Diet, microbiota, and gut permeability-the unknown triad in rheumatoid arthritis. Front Med 5:349. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2018.00349

Zhang X, Zhang D, Jia H, Feng Q, Wang D, Liang D, Wu X, Li J, Tang L, Li Y, Lan Z, Chen B, Li Y, Zhong H, Xie H, Jie Z, Chen W, Tang S, Xu X, Wang X, Cai X, Liu S, Xia Y, Li J, Qiao X, al-Aama JY, Chen H, Wang L, Wu QJ, Zhang F, Zheng W, Li Y, Zhang M, Luo G, Xue W, Xiao L, Li J, Chen W, Xu X, Yin Y, Yang H, Wang J, Kristiansen K, Liu L, Li T, Huang Q, Li Y, Wang J (2015) The oral and gut microbiomes are perturbed in rheumatoid arthritis and partly normalized after treatment. Nat Med 21:895–905. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.3914

Mohamed Said MS (2013) The effects of the Ramadan month of fasting on disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Turk J Rheumatol 28:189–194. https://doi.org/10.5606/tjr.2013.3147

Assar S, Almasi P, Almasi A (2020) Effect of Islamic fasting on the severity of rheumatoid arthritis. J Nutr Health 8:28–33. https://doi.org/10.22038/jnfh.2019.39142.1184

Al-Dubeikil KY, Abdul-Lateef WK (2003) Ramadan fasting and rheumatoid arthritis. Bahrain Med Bull 25:68–70

Müller H, de Toledo FW, Resch KL (2001) Fasting followed by vegetarian diet in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Scand J Rheumatol 30:1–10

Sköldstam L, Larsson L, Lindström FD (1979) Effect of fasting and lactovegetarian diet on rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol 8:249–255. https://doi.org/10.3109/03009747909114631

Kjeldsen-Kragh J, Haugen M, Borchgrevink CF et al (1991) Controlled trial of fasting and one-year vegetarian diet in rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet Lond Engl 338:899–902. https://doi.org/10.1016/0140-6736(91)91770-u

Gumaa KA, Mustafa KY, Mahmoud NA, Gader AM (1978) The effects of fasting in Ramadan. 1. Serum uric acid and lipid concentrations. Br J Nutr 40:573–581. https://doi.org/10.1079/bjn19780161

Schmahl FW, Metzler B (1991) The health risks of occupational stress in islamic industrial workers during the Ramadan fasting period. Pol J Occup Med Environ Health 4:219–228

Azizi F, Azizi F (2010) Islamic fasting and health. Ann Nutr Metab 56:273–282. https://doi.org/10.1159/000295848

Habib G, Badarny S, Khreish M, Khazin F, Shehadeh V, Hakim G, Artul S (2014) The impact of Ramadan fast on patients with gout. J Clin Rheumatol Pract Rep Rheum Musculoskelet Dis 20:353–356. https://doi.org/10.1097/RHU.0000000000000172

Goldring MB, Otero M (2011) Inflammation in osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 23:471–478. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOR.0b013e328349c2b1

Bahijri SM, Ajabnoor GM, Borai A, al-Aama JY, Chrousos GP (2015) Effect of Ramadan fasting in Saudi Arabia on serum bone profile and immunoglobulins. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab 6:223–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042018815594527

Kormi SMA, Ardehkhani S, Kerachian MA (2017) The effect of Islamic fasting in Ramadan on osteoporosis. J Nutr Health 5:74–77. https://doi.org/10.22038/jfh.2017.22955.1086

BaHammam AS, Almeneessier AS (2020) Recent evidence on the impact of Ramadan diurnal intermittent fasting, mealtime, and circadian rhythm on cardiometabolic risk: a review. Front Nutr 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2020.00028

Alomi YA, Al-Jarallah SM, Adouh AA, Alghuraibi MI (2019) Medication therapy during the holy month of Ramadan Pharmacol Toxicol Biomed Rep 5. https://doi.org/10.5530/PTB.2019.5.10

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ben Nessib, D., Maatallah, K., Ferjani, H. et al. The potential effect of Ramadan fasting on musculoskeletal diseases: new perspectives. Clin Rheumatol 40, 833–839 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-020-05297-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-020-05297-9