Abstract

Purpose

We aimed to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis comparing postoperative outcomes in inguinal hernia repair with TIPP versus Lichtenstein technique.

Methods

Cochrane Central, Scopus, and PubMed were systematically searched for studies comparing TIPP and Lichtenstein´s technique for inguinal hernia repair. Outcomes assessed were operative time, bleeding, surgical site events, hospital stay, the Visual Analogue Pain Score, chronic pain, paresthesia rates, and recurrence. Statistical analysis was performed using RevMan 5.4.1. Heterogeneity was assessed with I2 statistics and random-risk effect was used if I2 > 25%.

Results

790 studies were screened and 44 were thoroughly reviewed. A total of nine studies, comprising 8428 patients were included, of whom 4185 (49.7%) received TIPP and 4243 (50.3%) received Lichtenstein. We found that TIPP presented less chronic pain (OR 0.43; 95% CI 0.20–0.93 P = 0.03; I2 = 84%) and paresthesia rates (OR 0.27; 95% CI 0.07–0.99; P = 0.05; I2 = 63%) than Lichtenstein group. In addition, TIPP was associated with a lower VAS pain score at 14 postoperative day (MD − 0.93; 95% CI − 1.48 to − 0.39; P = 0.0007; I2 = 99%). The data showed a lower operative time with the TIPP technique (MD − 7.18; 95% CI − 12.50, − 1.87; P = 0.008; I2 = 94%). We found no statistical difference between groups regarding the other outcomes analyzed.

Conclusion

TIPP may be a valuable technique for inguinal hernias. It was associated with lower chronic pain, and paresthesia when compared to Lichtenstein technique. Further long-term randomized studies are necessary to confirm our findings.

Study registration A review protocol for this meta-analysis was registered at PROSPERO (CRD42023434909).

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

As stated by recent guidelines for groin hernia management, no consensus can be made about which technique is preferred for open inguinal hernia repair [1]. Many techniques exist and the mesh can be placed anteriorly, as used in the Lichtenstein repair, or posteriorly with open preperitoneal techniques [2]. As first described by Pélissier [3], the TIPP technique dissects the preperitoneal space without transecting the transversalis fascia through the dilated internal ring in an indirect hernia or hernia sac in a direct hernia. This technique avoids opening the inguinal floor as in other open preperitoneal inguinal hernia repair techniques through groin incisions such as Kugel’s [4] and Read-Rives techniques [5]. Some studies suggest that the standard TIPP technique may present fewer recurrence rates when compared to other open preperitoneal mesh techniques due to the preservation of transversalis fascia anatomy [6].

Although Lichtenstein is the most commonly performed inguinal hernia repair technique, some studies suggest that placement of the mesh posteriorly and minimizing suture fixation may decrease postoperative pain and quality of life-related symptoms such as paresthesia after surgery [7,8,9,10]. Although the rates of chronic groin pain following hernia repair varies widely in the literature, studies have reported up to 21.5% chronic pain incidence following Lichtenstein inguinal hernia repair [1, 11, 12].

A meta-analysis from 2012 compared all open preperitoneal approaches to the Lichtenstein technique, founding fewer recurrence rates for preperitoneal techniques compared to Lichtenstein, but no statistically significant results regarding chronic pain, immediate postoperative complications, or paresthesia rates [2]. However, the study included several different open preperitoneal techniques, limiting the applicability of their findings to individual techniques.

As no previous meta-analysis compared the standard TIPP and Lichtenstein techniques, we aimed to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis on postoperative outcomes comparing the two methods.

Materials and methods

Registration

This systematic review and meta-analysis are conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement. A description of the study protocol was registered to the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO registration number CRD42023434909).

Study eligibility

We used as inclusion criteria and selection studies that (1) describe the standard TIPP technique; (2) evaluate postoperative outcomes; (3) used the standard Lichtenstein open repair technique as control group.

Information source and search strategy

The PubMed (Medline), EMBASE, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials databases were searched without date or language restrictions on studies that met eligibility criteria published from inception up to March 2023. The search strategy included the following terms: “inguinal hernia”, “groin hernia”, “transinguinal”, “TIPP”, “transinguinal preperitoneal”, “Lichtenstein”, and “open anterior”, and was conducted by two authors. References from the included studies were also reviewed.

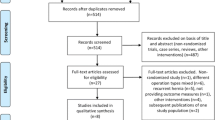

Study selection

After excluding duplicate studies, two reviewers independently screened the studies identified by the search strategy for eligibility. If the title and abstract showed potential eligibility or doubt about eligibility, the full text was accessed for final decision. If studies showed ineligibility during the full-text assessment, the reasons were documented. If there was doubt between the two authors' decisions, a third author was consulted for the final decision.

Long-term analysis from previous randomized controlled trials were used for outcomes that required long-term data and were not superimposed on original studies in the statistical analysis.

Data collection

The data collection was performed independently by the two authors, who did the study selection using a predefined data extraction label. After the data collection, the data was compared, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion. A last review was conducted by a third author.

Data items and outcomes

The study characteristics collected were year of publication, study period, study design, sample size, and participant specification data. The data collected included: operative time, surgery conversion rates, intraoperative bleeding, intraoperative complications, hospital stay, re-operation rates, hematoma, wound infection, seroma. Immediate and long-term postoperative pain rates, Visual Analogue Pain (VAS) score [13], sexual disturbance rates, numbness rates (paresthesia), general recurrence rates, and median follow-up time.

Risk of bias assessment

The risk of bias in the RCT was assessed using the Revised Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool (RoB 2) [14], assessing randomization, concealment, blinding, intention to treat, baseline comparisons, concomitant interventions, and completeness of follow-up. Nonrandomized studies biases were assessed using the ROBINS-I [15]. Two authors assessed the risk of bias independently in each study and discrepancies were resolved by a third author after discussing the reasons for the divergence.

Data analysis

The systematic review and meta-analysis were performed in accordance with recommendations from the Cochrane Collaboration and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement guidelines. The study and patient's baseline characteristics are presented descriptively. Based on the normality, the numerical data are presented as mean with standard deviation (SD) or median with interquartile range (IQR). Normality was checked by plotting a frequency distribution. Categorical data are presented as percentages and were collected as the number of events and number of individuals at risk to produce summary effects of both surgical hernia repair methods in terms of odds ratio (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Cochran Q test, I2 statistics, and visual inspection of the forest plots were used to assess heterogeneity. If the visual inspection was suggestive of heterogeneity in effect size, the p value < 0.10 or I2 statistics > 25%, heterogeneity was considered significant, and a random-effect model was used. For statistically significant results with high heterogeneity, a sensitivity analysis was performed. The statistical analysis was performed using Review Manager 5.4 (Nordic Cochrane Center, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark).

Results

Study selection

The primary search yielded 790 results. After removing duplicates, 446 studies were screened by title and abstracts, of which 402 were excluded by not meeting the inclusion criteria, and 44 were selected for full reading. After the final reading, 09 studies were included (Fig. 1).

Study and patient characteristics

Study and patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. We found five randomized controlled trials (RCT), of which two were long-term follow-up trials from two previous RCTs, one prospective cohort study, two retrospective cohorts’ studies, and one database comparative study, all published between 2009 and 2023.

The nine studies comprised 9804 patients, of whom 94.1% were men. 5696 (58.1%) patients received TIPP and 4108 (41.9%) received Lichtenstein inguinal hernia repair. All the studies included patients older than 18 years old. None of the studies included patients admitted for emergency conditions such as strangulated hernia. All studies reported mean patient ages between 43 and 60.8 years old. Body mass index ranged from 24.5 and 29.4 kg/m2. All the studies used PolySoft™ HerniaPatch with a memory ring for the TIPP technique. For the Lichtenstein technique, the meshes varied between Soft Mesh™ (Bard), Vypro II/Ultrapro Mesh™, Ethicon, and Parietex ProGrip™ self-fixating mesh.

Pooled analysis of all studies

Chronic pain

Five studies evaluated chronic pain at 3 months postoperatively. Less chronic pain was found on TIPP against the Lichtenstein group, with rates of 7.19% and 11.7%, respectively (OR 0.43; 95% CI 0.20, 0.93; P = 0.03; I2 = 84%) (Fig. 2). After the sensitivity analysis excluding the only study presenting heterogeneity by visual analysis (Berrevoet 2010 [16]), we still found results supporting TIPP against Lichtenstein, with a low heterogeneity (OR 0.66; 95% CI 0.56, 0.77; P < 0.00001; I2 = 0%).

Two RCTs and one prospective cohort study performed a 1-year pain rates comparison, but the meta-analysis found no statistically significant difference (OR 0.25; 95% CI 0.05, 1.26; P = 0.09; I2 = 89%), located in Supplementary information 1 (S1).

VAS score (14 days postoperatively)

VAS score was measured at 14 days after surgery in three studies, including two RCTs, and a lower median VAS score was found for the TIPP group (MD − 0.93; 95% CI − 1.48, − 0.39; P = 0.0007; I2 = 99%) (Fig. 3).

Paresthesia rates

The analysis comparing paresthesia rates included data from three RCTs and 2 cohort studies and found less rates of paresthesia for TIPP against Lichtenstein, 3.89% and 16.05% respectively (OR 0.27; 95% CI 0.07, 0.99; P = 0.05; I2 = 63%) (Fig. 4).

Recurrence rates

No difference with statistical significance was found between TIPP (2.45%) and Lichtenstein (3.45%) regarding general recurrence (OR 0.66; 95% CI 0.34, 1.28; P = 0.22; I2 = 0%). The analysis was performed with three RCTs and two cohort studies with at least 6 months of follow-up. The forest plot regarding recurrence rates is found in Supplementary information 1 (S1).

Operative time

Operative time was assessed by four studies, including 3 RCTs and one cohort study. Data showed a lower operative time in minutes for the TIPP technique (MD − 7.18; 95% CI − 12.50, − 1.87; P = 0.008; I2 = 94%) (Fig. 5). After performing a sensitivity analysis for this outcome excluding the nonrandomized study, we still found a lower operative time in TIPP group with a low heterogeneity rate (MD − 4.49; 95% CI − 5.98, − 2.99; P < 0.00001; I2 = 0%).

Length of hospital stay

We found no statistical difference between groups regarding length of hospital stay, in hours (MD − 11.66; 95% CI − 24.95, 1.63; P = 0.09; I2 = 97%) in the meta-analysis containing 3 nonrandomized studies. The forest plot regarding hospitalization is found in Supplementary information 1 (S1).

Reoperation rates

Three studies, including two RCTs and one nonrandomized study, reported reoperation rates. No statistical significance was identified by the meta-analysis (OR 0.84; 95% CI 0.41, 1.69; P = 0.62; I2 = 17%). The forest plot regarding reoperation rates is found in Supplementary information 1 (S1).

Wound infection

Two RCTs and one prospective cohort reported early postoperative complications. No difference was found between TIPP and Lichtenstein regarding wound infection (OR 0.34; 95% CI 0.09, 1.25; P = 0.10; I2 = 0%). All the data analysis and forest plots regarding postoperative complications are found in Supplementary information 1 (S1).

Seroma

Two RCTs and one prospective cohort reported seroma rates. No statistically significant difference was identified (OR 0.5; 95% CI 0.16, 1.58; P = 0.24; I2 = 2%). All the data analysis and forest plots regarding postoperative complications are found in Supplementary information 1 (S1).

Hematoma

Two RCTs and one prospective cohort reported hematomas. No statistically significant difference was identified between the groups (OR 0.88; 95% CI 0.43, 1.79; P = 0.72; I2 = 2%). All the data analysis and forest plots regarding postoperative complications are found in Supplementary information 1 (S1).

Risk of bias

The overall risk of bias was low to some concerns risk for the RCTs due to deviations from intended interventions, and measurement of the outcome’s biases, which are found in 3 of the 5 RCTs. The nonrandomized studies showed serious and critical risk of bias due to nonmeasured confounding factors, bias due to the selection of participants, deviations from intended interventions, measurement of outcomes and selection of reported results. The risk of bias domains and overall risks of included studies are summarized in Fig. 6.

Discussion

Groin hernias are one of the most common surgical conditions in the world and over 20 million patients undergo groin hernia repair annually [1]. In men, the literature estimates that the prevalence of groin hernia throughout their lifetime ranges from 27 to 43%, while in women, it is between 3 and 6% [21]. Although watchful waiting is an option for asymptomatic patients, approximately two-thirds of patients with inguinal hernias have symptoms and will require surgical intervention [22,23,24].

There are numerous surgical techniques described for inguinal hernia repair. Mesh repair, whether performed through an open procedure or a minimally invasive approach, is recommended as the preferred initial approach, assuming the surgeon possesses adequate expertise in the specific procedure [1]. The optimal surgical approach should have the following characteristics: minimal risk of complications, such as pain and recurrence, relatively straightforward to acquire proficiency, swift postoperative recovery, consistent outcomes, and cost-effectiveness [1].

Among the open inguinal hernia repair techniques, Lichtenstein´s herniorrhaphy has become the most commonly performed technique worldwide [1]. This method is reproducible and has low recurrence rates [25, 26]. Even though the Lichtenstein technique has brought improvement in the recurrence risk for hernias, one of its major drawbacks is postoperative chronic groin pain, defined as pain for more than 3 months postoperatively, which can range from 8 to 40% [11, 27,28,29]. Therefore, the best open method for inguinal hernia repair remains debatable.

It has been hypothesized that TIPP may be associated with decreased postoperative pain compared to the Lichtenstein technique due to the preperitoneal placement of the mesh and lack of suture fixation, which is concordant with our study findings. The mesh placement behind the abdominal wall musculature minimizes the presence of foreign body material in close proximity to peripheral nerves such as the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves. Also, placing the mesh in this location minimizes the need for suture fixation, which could also cause chronic pain by inadvertently injuring nerves while placing the sutures [11, 30]. However, the technique to develop the preperitoneal space varies importantly in their initial incision sites, mesh placement, and several techniques are described in the literature. The preperitoneal space can be developed through an anterior approach such as in the TIPP [3], Kugel [4], Horton/Florence [31], and Read’s technique [32]; or through a posterior approach like in the Nyhus [33], TREPP [28], Stoppa [34] or Ugahary [35] techniques. This differentiation is important as preperitoneal anterior approaches can result in scar tissue in both anterior and posterior planes, resulting in challenging reoperations in the setting of a future recurrence.

However, few studies compare different open preperitoneal techniques. A randomized study demonstrated benefits regarding TIPP compared to TREPP in recurrence rates, but better short-term pain outcomes for TREPP with similarly low rates of chronic pain between both techniques [36]. A randomized study conducted by Posthuma et al. found less chronic pain for Laparoscopic Totally Extraperitoneal (TEP) technique at 1 year compared to the TIPP technique, with the same recurrence and reoperation rates [37]. However, no difference in chronic pain and recurrence rates was found between TIPP and Laparoscopic TEP in the study conducted by Haroon et al.[38]. A database analysis compared TIPP, Transrectus Sheath Preperitoneal (TREPP), and minimally invasive trans-abdominal Preperitoneal (TAPP) techniques and a comparable chronic pain rate was found between those techniques [19]. A randomized controlled trial comparing Kugel Technique to TIPP found reduced chronic pain rates at 1 year postoperatively for TIPP, with a statistically significant result [39].

Chronic pain is one of the most common complications following inguinal hernia repair [40], and has devasting consequences to a patient quality of life [41, 42]. Iftikhar et al. evaluated the quality of life of patients with postoperative chronic groin pain and suggested that its most important repercussions are related to physical limitations and its consequences on mental and social health [41]. Generally, Lichtenstein repair has been associated with up to 21.5% of chronic groin pain, and TIPP has been reported to have 2.8–12.2% postoperative chronic groin pain [7,8,9, 11, 28]. Bokkerinkk et al. compared TIPP and Lichtenstein and found 3.5% and 12.9% chronic pain rates, respectively [7]. Berrevoet et al. found a 5.1% rate of chronic pain with Lichtenstein and 2.8% with TIPP [16]. Our results also showed less chronic pain with TIPP, and this technique can potentially minimize the number of patients that develop this complication following open inguinal hernia repair.

Nonetheless, in our study, the studies which reported chronic pain outcomes showed several differences in methodological quality, of which only one was a RCT, and the other four were observational studies with serious and critical risk of bias. The single included RCT obtained no statistical difference among groups [9]. Even though the pooled result shows statistically significant odds in favor of the TIPP technique, the inherent risk of a systematic error in observational studies must be considered.

Although the lack of fixation in the TIPP technique may play a role in minimizing postoperative pain, studies comparing self-gripping mesh, glue fixation or suture fixation for the Lichtenstein technique found no significant differences [43,44,45,46]. A 5-year follow-up randomized study evaluated self-gripping mesh, glue use, and suture fixating techniques and found no statistically significant differences between the groups regarding pain, recurrence rates, and sensory disturbance rates [11]. A meta-analysis from 2018 comparing self-gripping and sutured mesh also showed no statistically significant difference between the two groups other than shorter operative time with self-gripping mesh [46].

Despite the benefit of decreased pain in our study, it is important to emphasize an important limitation of TIPP. Given that TIPP is an anterior approach to the preperitoneal space, this results in the creation of scar tissue in both anterior and posterior planes, resulting in significant challenges in reoperation for recurrences following TIPP. Current guidelines stipulate that, in the setting of a recurrence, inguinal hernias should be approached through virgin planes, which wouldn’t exist in the setting of a recurrence from TIPP [1]. Reoperative groin surgery poses a greater technical difficulty, making anatomy identification more complex and increasing the risk of injuries [47]. There is limited data on reoperations following TIPP. In a retrospective cohort of 33 patients with recurrences following TIPP, van Silfhout et al. [48] reported that 18 patients underwent Lichtenstein repair, and 13 underwent re-TIPP. The complications noted on a mean follow-up of 4.3 months were 8 superficial hematomas that did not require intervention, 1 urinary tract infection and 1 hernia recurrence [48]. This suggests that an anterior approach for recurrences following TIPP is feasible. Ultimately, recurrences following TIPP should be approached by the technique that the surgeon is more comfortable with, as both anterior and posterior approaches can be challenging in this scenario.

There are significant limitations of our study. Although we included data from five randomized studies, we still could not perform subgroup analysis for our outcomes and included retrospective studies that carry potential biases inherent to retrospective data collection. Also, there was a lack of information reported in the included studies that could have affected our results, such as preoperative groin pain, hernia size and classification. In addition, some of the included studies [17, 19, 20] didn’t provide complete baseline characteristics, which can affect our results. There was significant variability in Patient Reported Outcomes (PROs) tools used to measure postoperative quality of life in the included studies, and we could not perform a meta-analysis of any PROs. These limitations highlight that further randomized studies with granular hernia-specific perioperative data, including PROs, are still needed to determine the role of TIPP in the armamentarium of the abdominal wall surgeon for managing patients with inguinal hernias.

Conclusion

TIPP may be a valuable technique for inguinal hernias considering it was associated with lower 14-day postoperative pain, chronic pain, and sensory disturbance compared to the Lichtenstein technique. Further randomized or larger prospective studies with propensity score matching are necessary to confirm our findings and evaluate the postoperative complications, learning curves, and recurrence rates.

Data availability

Not applicable.

References

HerniaSurge Group (2018) International guidelines for groin hernia management. Hernia 22(1):1–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-017-1668-x

Li J, Ji Z, Cheng T (2012) Comparison of open preperitoneal and Lichtenstein repair for inguinal hernia repair: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Surg 204(5):769–778. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2012.02.010

Pélissier EP, Blum D, Ngo P, Monek O (2008) Transinguinal preperitoneal repair with the Polysoft patch: prospective evaluation of recurrence and chronic pain. Hernia 12(1):51–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-007-0278-4

Kugel RD (1999) Minimally invasive, nonlaparoscopic, preperitoneal, and sutureless, inguinal herniorrhaphy. Am J Surg 178(4):298–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9610(99)00181-6

Rives J, Lardennois B, Flament JB, Convers G (1973) The Dacron mesh sheet, treatment of choice of inguinal hernias in adults. Apropos of 183 cases. Chirurgie 99(8):564–575

Andresen K, Rosenberg J (2017) Open preperitoneal groin hernia repair with mesh: a qualitative systematic review. Am J Surg 213(6):1153–1159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.01.014

Bökkerink WJV, Koning GG, Malagic D, van Hout L, van Laarhoven CJHM, Vriens PWHE (2019) Long-term results from a randomized comparison of open transinguinal preperitoneal hernia repair and the Lichtenstein method (TULIP trial). Br J Surg 106(7):856–861. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.11178

Bökkerink WJV, van Meggelen MGM, van Dijk JP, Čadanová D, Mollen RMHG (2023) Long-term results of the SOFTGRIP trial: TIPP versus ProGrip Lichtenstein’s inguinal hernia repair. Hernia 27(1):139–145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-021-02542-1

Čadanová D, van Dijk JP, Mollen RMHG (2017) The transinguinal preperitoneal technique (TIPP) in inguinal hernia repair does not cause less chronic pain in relation to the ProGrip technique: a prospective double-blind randomized clinical trial comparing the TIPP technique, using the PolySoft mesh, w. Hernia 21(1):17–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-016-1522-6

Koning GG, Keus F, Koeslag L, Cheung CL, Avçi M, Van Laarhoven CJHM et al (2012) Randomized clinical trial of chronic pain after the transinguinal preperitoneal technique compared with Lichtenstein’s method for inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg 99(10):1365–1373. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.8862

Matikainen M, Vironen J, Kössi J, Hulmi T, Hertsi M, Rantanen T et al (2021) Impact of mesh and fixation on chronic inguinal pain in Lichtenstein hernia repair: 5-year outcomes from the Finn Mesh Study. World J Surg 45(2):459–464. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-020-05835-1

Lyu Y, Cheng Y, Wang B, Du W, Xu Y (2020) Comparison of endoscopic surgery and Lichtenstein repair for treatment of inguinal hernias: a network meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 99(6):e19134

Genti G, Balint G, Borbas E (1980) Visual analogue pain scales. Ann Rheum Dis 39:414. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.39.4.414-a

Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I et al (2019) RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 366:l4898. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4898

Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M et al (2016) ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 355:i4919. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i4919

Berrevoet F, Maes L, Reyntjens K, Rogiers X, Troisi R, De Hemptinne B (2010) Transinguinal preperitoneal memory ring patch versus Lichtenstein repair for unilateral inguinal hernias. Langenbeck’s Arch Surg 395(5):557–562. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-009-0544-2

Djokovic A, Delibegovic S (2021) Tipp versus the Lichtenstein and Shouldice techniques in the repair of inguinal hernias–short-term results. Acta Chir Belg 121(4):235–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/00015458.2019.1706323

Koning GG, Koole D, De Jongh MAC, De Schipper JP, Verhofstad MHJ, Oostvogel HJM et al (2011) The transinguinal preperitoneal hernia correction vs Lichtenstein’s technique; Is TIPP top? Hernia 15(1):19–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-010-0744-2

Hurel R, Bouazzi L, Barbe C, Kianmanesh R, Romain B, Gillion JF et al (2023) Lichtenstein versus TIPP versus TAPP versus TEP for primary inguinal hernia, a matched propensity score study on the French Club Hernie Registry. Hernia. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-023-02737-8

Khan H (2021) A comparative study of Lichtenstein tension free mesh repair vs transinguinal pre-peritoneal mesh repair for inguinal hernias. J Cardiovasc Dis Res 12(4):2297–2301

Kingsnorth A, LeBlanc K (2003) Hernias: inguinal and incisional. Lancet (London, England) 362(9395):1561–1571. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14746-0

Chung L, Norrie J, O’Dwyer PJ (2011) Long-term follow-up of patients with a painless inguinal hernia from a randomized clinical trial. Br J Surg 98(4):596–599. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.7355

Fitzgibbons RJ, Ramanan B, Arya S, Turner SA, Li X, Gibbs JO et al (2013) Long-term results of a randomized controlled trial of a nonoperative strategy (watchful waiting) for men with minimally symptomatic inguinal hernias. Ann Surg 258(3):508–514. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182a19725

Hair A, Paterson C, Wright D, Baxter JN, O’Dwyer PJ (2001) What effect does the duration of an inguinal hernia have on patient symptoms? J Am Coll Surg 193(2):125–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1072-7515(01)00983-8

Nordin P, Bartelmess P, Jansson C, Svensson C, Edlund G (2002) Randomized trial of Lichtenstein versus Shouldice hernia repair in general surgical practice. Br J Surg 89(1):45–49. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.01960.x

Willaert W, De Bacquer D, Rogiers X, Troisi R, Berrevoet F (2012) Open preperitoneal techniques versus Lichtenstein repair for elective inguinal hernias. Cochrane DATABASE Syst Rev 7:CD008034. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008034.pub2

Eklund A, Montgomery A, Bergkvist L, Rudberg C (2010) Chronic pain 5 years after randomized comparison of laparoscopic and Lichtenstein inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg 97(4):600–608. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.6904

Koning GG, Andeweg CS, Keus F, van Tilburg MWA, van Laarhoven CJHM, Akkersdijk WL (2012) The transrectus sheath preperitoneal mesh repair for inguinal hernia: technique, rationale, and results of the first 50 cases. Hernia 16(3):295–299. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-011-0893-y

Callesen T, Bech K, Kehlet H (1999) Prospective study of chronic pain after groin hernia repair. Br J Surg 86(12):1528–1531. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2168.1999.01320.x

Sun P, Cheng X, Deng S, Hu Q, Sun Y, Zheng Q (2017) Mesh fixation with glue versus suture for chronic pain and recurrence in Lichtenstein inguinal hernioplasty. Cochrane database Syst Rev 2(2):CD010814. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010814.pub2

Horton MD, Florence MG (1993) Simplified preperitoneal marlex hernia repair. Am J Surg 165(5):595–599. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9610(05)804

Read RC, Barone GW, Hauer-Jensen M, Yoder G (1993) Properitoneal prosthetic placement through the groin: the anterior (Mahorner-Goss, Rives-Stoppa) approach. Surg Clin N Am 73(3):545–555. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0039-6109(16)46036-6

Nyhus LM (2003) The posterior (preperitoneal) approach and iliopubic tract repair of inguinal and femoral hernias—an update. Hernia 7(2):63–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-002-0113-x

Stoppa RE, Rives JL, Warlaumont CR, Palot JP, Verhaeghe PJ, Delattre JF (1984) The use of dacron in the repair of hernias of the groin. Surg Clin N Am 64(2):269–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0039-6109(16)43284-6

Ugahary F, Simmermacher RKJ (1998) Groin hernia repair via a grid-iron incision: an alternative technique for preperitoneal mesh insertion. Hernia 2:123–125

Bökkerink WJV, Koning GG, Vriens PWHE, Mollen RMHG, Harker MJR, Noordhof RK et al (2021) Open preperitoneal inguinal hernia repair, TREPP versus TIPP in a randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg 274(5):698–704. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000005130

Posthuma JJ, Sandkuyl R, Sloothaak DA, Ottenhof A, van der Bilt JDW, Gooszen JAH et al (2023) Transinguinal preperitoneal (TIPP) vs endoscopic total extraperitoneal (TEP) procedure in unilateral inguinal hernia repair: a randomized controlled trial. Hernia 27(1):119–125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-022-02651-5

Haroon M, Al-Sahaf O, Eguare E, Morarasu S, Wagner P, Batt R et al (2019) Postoperative outcomes and patient’s satisfaction after hybrid TIPP with UHS and TEP repair for inguinal hernias: a single-centre retrospective comparative study. Chirurgia (Bucur) 114(1):57–66. https://doi.org/10.21614/chirurgia.114.1.57

Okinaga K, Hori T, Inaba T, Yamaoka K (2016) A randomized clinical study on postoperative pain comparing the Polysoft patch to the modified Kugel patch for transinguinal preperitoneal inguinal hernia repair. Surg Today 46(6):691–698. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-015-1228-x

Bjurstrom MF, Nicol AL, Amid PK, Chen DC (2014) Pain control following inguinal herniorrhaphy: current perspectives. J Pain Res 7:277–290. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S47005

Iftikhar N, Kerawala A (2021) Quality of life after inguinal hernia repair. Pol Przegl Chir 93(3):1–5. https://doi.org/10.5604/01.3001.0014.8218

Srsen D, Druzijanić N, Pogorelić Z, Perko Z, Juricić J, Kraljević D et al (2008) Quality of life analysis after open and laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair–retrospective study. Hepatogastroenterology 55(88):2112–2115

Agarwal PK, Sutrave T, Kaushal D, Vidua R, Malik R, Maurya AP (2023) Comparison of postoperative chronic groin pain after repair of inguinal hernia using nonabsorbable versus absorbable sutures for mesh fixation. Cureus 15(2):e35562. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.35562

Emral AC, Anadol AZ, Kozan R, Cetinkaya G, Altiner S, Aytac AB (2022) Comparison of the results of using a self-adhesive mesh and a polypropylene mesh in open inguinal hernia repair: a prospective randomized controlled study. Pol Przegl Chir 94(6):46–53. https://doi.org/10.5604/01.3001.0015.7674

Zamkowski M, Ropel J, Makarewicz W (2022) Randomised controlled trial: standard lightweight mesh vs self-gripping mesh in Lichtenstein procedure. Pol Przegl Chir 94(6):38–45. https://doi.org/10.5604/01.3001.0015.7928

Molegraaf M, Kaufmann R, Lange J (2018) Comparison of self-gripping mesh and sutured mesh in open inguinal hernia repair: a meta-analysis of long-term results. Surgery 163(2):351–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2017.08.003

Schwab R, Conze J, Willms A, Klinge U, Becker HP, Schumpelick V (2006) Rezidivleistenhernienreparation nach vorangegangener netzimplantation. Eine herausforderung Chirurg 77(6):523–530. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00104-006-1158-7

van Silfhout L, van Hout L, Jolles M, Theeuwes HP, Bökkerink WJV, Vriens PWHE (2022) Treatment of recurrent inguinal hernia after transinguinal preperitoneal (TIPP) surgery: feasibility and outcomes in a case series. Hernia 26(4):1083–1088. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-021-02517-2

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept: CABS; Methodology, study selection, and data collection: CABS and YJMD; Statistical analysis: CABS, YJMD and ACDR; Manuscript draft: CABS, SMPF, RRHM, YJMD, and ACDR; Study supervision: SMPF and RL. All authors approved the final version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work related to its accuracy and integrity.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

R.L received payment/honoraria for lectures and presentations from Intuitive Surgical that are not related to this work. All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

As this concerns a literature review study, ethical approval was not required.

Human and animal rights

Not applicable.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Silveira, C.A.B., Poli de Figueiredo, S.M., Dias, Y.J.M. et al. Transinguinal preperitoneal (TIPP) versus Lichtenstein for inguinal hernia repair: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hernia 27, 1375–1385 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-023-02882-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-023-02882-0