Abstract

Purpose

Adolescent inguinal hernias are treated using high ligation or posterior wall suture repair with laparoscopic mesh implantation. This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of laparoscopic intracorporeal posterior wall suture repair without mesh implantation for treating adolescent indirect inguinal hernias.

Methods

Laparoscopic herniorrhaphy was performed between September 2012 and April 2015 in 244 patients aged 11–18 years who were diagnosed with indirect inguinal hernias at Damsoyu Hospital, Seoul, Korea. The patients were stratified by surgical procedure into the high-ligation (115 patients) and wall suture (129 patients) groups.

Results

Four (3.5%) of the 115 patients in the high-ligation group experienced recurrence, but those in the wall suture group did not. The difference in recurrence rates between these groups was significant (p < 0.001). The wall suture procedures were longer (mean 28.2 min) than the high-ligation procedures (mean 17.4 min) (p < 0.001). The lengths of postoperative hospital stays were similar in both groups. Few complications were observed: one patient developed hematoma and one developed seroma in the high-ligation group; two patients developed inguinal hematomas and one developed seroma in the wall suture group. Visual analog scale scores at 1 week after surgery and the mean times to return to normal activities were similar in both groups. No chronic inguinodynia after the operation in either group was observed.

Conclusions

Laparoscopic intracorporeal posterior wall suture repair without mesh implantation was effective for treating adolescent indirect inguinal hernias and resulted in fewer recurrences than those with high ligation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Inguinal hernia is a common condition in adolescents that requires surgical intervention, and its management has evolved from open surgery (high ligation, posterior wall suture repair, and tension-free surgery using synthetic mesh) to laparoscopic herniorrhaphy in recent years [1]. High ligation and posterior wall suture repair are the standard treatments in children and adults, respectively. Both methods are used in adolescents, and the choice of method depends on the surgeon [2]. High ligation and mesh implantation are widely performed in both open and laparoscopic approaches. Tissue repair methods using the anterior open approach have been reported, but few studies describing the laparoscopic approach have been published. To the best of my knowledge, there is no published report on laparoscopic tissue repair of adolescent inguinal hernias. Laparoscopic deep inguinal ring closure was performed to repair indirect inguinal hernias in animals in 1990 [3]. After noting a few recurrences in adolescents who underwent high ligation, the laparoscopic preperitoneal suture repair technique was adopted without mesh implantation for treating adolescent inguinal hernias. This study reports our experience with the laparoscopic posterior wall suture technique that can reduce recurrences in adolescents with indirect inguinal hernia.

Materials and methods

This retrospective study evaluated our experience with laparoscopic repair of adolescent inguinal hernias performed between September 2012 and April 2015 (Fig. 1). Adolescent patients aged 11–18 years who had undergone primary surgery were included; those who had undergone secondary surgeries were excluded. From September 2012 to December 2013, 115 patients (109 with a unilateral hernia and six with bilateral hernias) underwent laparoscopic high ligation, but on noting a few recurrences after this method, the posterior wall suture technique was adopted. From January 2014 to April 2015, 129 patients (124 with a unilateral hernia and five with bilateral hernias) underwent laparoscopic posterior wall suture. The size (diameter) of the hernia hole was measured based on the length of the laparoscopic instrument tip. All surgeries were performed by a highly experienced surgeon with 13 years of laparoscopic experience (SR Lee).

Laparoscopic herniorrhaphy

Laparoscopic herniorrhaphy was performed using high ligation or the wall suture technique, both of which were three-port laparoscopic procedures. The procedures were performed with the patient in the supine position under general anesthesia. The laparoscopy system included a 5.0-mm camera and 5.0-mm instruments. A transumbilical 5.0-mm incision was made, and a 5.0-mm trocar was used to create a CO2 pneumoperitoneum that was maintained at 7–10 mmHg. The other 5.0-mm instruments were inserted through separate 5.0-mm stab incisions on the lateral abdomen.

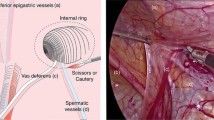

In high ligation, the peritoneum was closed with a continuous linear suture using nonabsorbable 3-0 silk after removing the hernial sac (Fig. 2). The wall sutures were placed as shown in Fig. 3. Initially, the bottom of the defect in the wall was tied and sutured in the upward direction to close the myopectineal orifice. The first stitch tied the lateral and medial walls with a space for the vas deferens and spermatic cord vessels to pass through without compression. The initial stitch was a suture of the inguinal ligament and the medial wall of the myopectineal orifice, avoiding the Triangle of Pain and Triangle of Doom (Fig. 4). The peritoneum was then closed in the downward direction using continuous sutures.

Laparoscopic high ligation with the posterior wall suture procedure. a Open deep inguinal ring (arrow). b Lateral incision of the peritoneum (arrow). c Detachment of the hernial sac from the vas deferens and spermatic cord vessels. d Removal of the hernial sac. e Initial lateral stitch of the myopectineal orifice avoiding the vas deferens (white arrow) and spermatic cord vessels (black arrow). f Medial stitch of the myopectineal orifice avoiding the vas deferens (white arrow) and spermatic cord vessels (black arrow). g Upward sutures for myopectineal orifice closure. h Finishing suture of the myopectineal orifice. i Continuous suture of the peritoneum. j Completion of high ligation

Change in shape after suture of the myopectineal orifice. a Circular shape of the myopectineal orifice after removal of the hernial sac. Preserved vas deferens and spermatic cord vessels are visible. The initial stitch was a suture of the inguinal ligament (white arrow) and the medial wall (black arrow) of the myopectineal orifice, avoiding the Triangle of Pain (black triangle) and Triangle of Doom (white triangle). b Change in the defect shape from a circle to a long line

Postoperative diet and follow-up

Drinking water was permitted after a 2-h observation. When patients could comfortably perform daily activities, such as walking and eating, and their monitored condition was satisfactory, they were discharged. Post-herniorrhaphy pain was evaluated using the visual analog scale (VAS). The medications prescribed for 3 days following discharge were the same in the two groups. Patients were telephoned 2 days after discharge to check for postoperative pain, wound status, and possible symptoms of hematoma or seroma. Routine outpatient follow-up included a physical examination after 7 days and annual telephonic interviews. Telephonic follow-up continued until the study ended in July 2017. Outpatient follow-up included routine questions and information obtained by a retrospective chart review. No patients were lost to follow-up. The mean follow-up period was 50.5 (43–58) months in the high-ligation group and 32.9 (27–42) months in the wall suture group.

Statistical methods

All statistical analyses were performed using the R 3.3.2(R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria, http://www.R-project.org). Continuous variables were presented by mean and standard deviation (SD). Categorical variables were presented by frequency and percentage. The Shapiro–Wilk’s test was used to test for the normality of the continuous variables. Because not all continuous variables were normally distributed, our choice of statistical test of continuous variables became the Wilcoxon rank sum test. For categorical variables, the Fisher’s exact test or χ2 test was used. A p value ≤ 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Patient clinical characteristics

The clinical characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. All patients had indirect inguinal hernias, and no patient was converted to open surgery. Both groups included a high proportion of males (74.8 vs. 74.4%), and between-group differences in age, sex, body mass index, laterality, herniated organs, and defect size were not significant. Both groups had more right unilateral hernias (63.5 vs. 61.2%) as well as bilateral hernias (5.2 vs. 3.9%). The omentum was the most frequently herniated organ in both groups (93.9 vs. 98.4%). Two patients in the high-ligation group and seven in the wall suture group had incarcerated hernias. Hernia defect sizes in the high-ligation (2.37 ± 0.52 cm; range 1.60–3.62 cm) and wall repair (mean 2.41 ± 0.58 cm; range 1.59–3.65 cm) groups were not significantly different.

Postoperative outcomes

Postoperative outcomes are shown in Table 2. Hernial sac removal and suturing proceeded without any damage to the vas deferens and spermatic cord vessels. The mean operative time was longer in the wall suture group (mean 28.2 ± 12.5 min; range 10–75 min) than that in the high-ligation group (mean 17.4 ± 8.81 min; range 7–65 min; p < 0.001). The mean lengths of postoperative hospital stays and 1-week post-herniorrhaphy pain scores were not significantly different between the two groups. The patients in both groups reported slight pain, with similar VAS scores of 1.0 ± 1.0 (range 0–4). The shape of the deep inguinal ring changed from a circle to a line (Fig. 4). The following complications were observed: one patient with hematoma and one with seroma in the high-ligation group and two patients with hematomas and one with seroma in the wall suture group. The difference between the groups was not significant, and the hematomas and seromas resolved with conservative treatment. Patients in the high-ligation group returned to normal activity in a mean of 3.48 days, which was similar to the mean of 3.59 days noted in the wall suture group. There was no chronic inguinodynia after the operation in the two groups. Four recurrences in the high-ligation group (3.5%) but none in the wall repair group occurred before the last follow-up (p = 0.048). There were three recurrences on the medial side of the previous sutures and one on the lower side of the previous sutures (Fig. 5). The mean interval from the date of surgery to recurrence was 7.5 ± 4.1 (range 4–12) months, and all recurrences occurred within 12 months after surgery.

Recurrent inguinal hernias in adolescents. a An 11-year-old male who had a recurrence at 4 months postoperatively. Right indirect inguinal hernia recurrence (white arrow) on the medial side of previous sutures (black arrow). b An 18-year-old male who had a recurrence at 12 months postoperatively. Left indirect inguinal hernia recurrence (white arrow) on the lower side of previous sutures (black arrow)

Discussion

Inguinal herniorrhaphy is a widely applied surgical correction procedure, but no single procedure is widely accepted to be the best. Open or laparoscopic high ligation is adequate for laparoscopic herniorrhaphy in pediatric patients. Posterior wall suture repair or tension-free repair with various types of mesh by open surgery and covering hernia defects with synthetic mesh by laparoscopic herniorrhaphy are adequate for adult patients. Both open anterior and laparoscopic approaches are used for treating adolescent patients [2], and the reported recurrence rates and complications vary depending on the technique used [4]. Even with the same surgical procedure, intraoperative and general postoperative complication and recurrence rates differ with patient age and the type and severity of the hernial defect [5, 6]. Recurrence rates of 0–6% have been reported; common complications include hematoma, seroma, and pain [7]. The myopectineal wall suture method in this study was performed after several recurrences after high ligation in adolescent hernia patients.

Whether to use a mesh is controversial and depends on the choice of the surgeon [2]. The use of a mesh reduces the recurrence rate, and the tension-free method reduces postoperative pain. However, if the pain and recurrence rate do not increase without the use of a mesh, I think it is better not to use a mesh for adolescent hernia patients. First, the insertion of a foreign body can have an impact (mesh adhesion, inflammation, etc.) because all the organs of the body are still growing. Second, patients and parents have a negative opinion regarding the use of a mesh because they think of hernia treatment as a minor operation. Adolescent patients are young but have physical characteristics similar to adult patients. In this study, the mean weight of patients in the high-ligation group was 48.6 kg and that of patients in the wall suture group was 42.3 kg. Currently, there are no treatment guidelines. The suture procedure used in this patient series was similar to Marcy repair in open anterior approach surgery. There was a report on the low rates of recurrence and complications associated with Marcy repair in children [8]. Tension-free mesh implantation is possible in both open anterior and laparoscopic approaches. However, physicians are under pressure to use mesh in adolescent patients, and there are concerns of recurrence following surgery using high ligation without mesh. Many reports on open anterior approach surgery for tissue repair without mesh have been published; in contrast, there are few reports on laparoscopic tissue repair without mesh. There is one report on suture repair of the deep inguinal ring in adolescent patients with inguinal hernia recurrence [9]. Four patients in this study developed recurrences after laparoscopic high ligation; thereafter, patients were treated using the new procedure, which included suture repair of the myopectineal orifice.

Generally, sutures are considered to cause tension compared with surgery to cover defects with mesh without suture. However, no strain or tension was noted when the myopectineal wall of the defect site was sutured using a continuous linear suture instead of the purse-string suture. The diameter of the deep inguinal ring is approximately 2.4 cm, and if the repair had resulted in tension that induced pain, the VAS pain scores should have increased. However, no difference was found in the 1-week VAS scores of the two groups. The intracorporeal wall suture included the iliopubic tract away from the Triangle of Pain and Triangle of Doom. When suturing, the femoral branch of the genitofemoral nerve is not well identified and care should be taken not to include it below the inguinal ligament. The entry point of the femoral branch of the genitofemoral nerve was 84% in the caudal location of the inguinal ligament and 5.2% in the medial direction in the anterior superior iliac spine [10]. Therefore, when suturing the lateral wall, it should be as close as possible to the inguinal ring. In the present study, no patients had chronic inguinodynia during follow-up. The length of hospital stay and time to return to daily activities were similar in the two groups. Seroma and hematoma are common early postoperative minor complications of endoscopic preperitoneal hernial repair. They may produce pain and require treatment, thereby delaying postoperative recovery. The incidence of seroma is approximately 5%, and various techniques have been used to reduce seroma development in adult inguinal hernia surgery [11, 12]. In this study, the occurrences of seroma and hematoma did not differ between the two groups. This result is consistent with that of other studies that found no increase in seroma development after transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) surgery [6].

The advantages of laparoscopic inguinal herniorrhaphy include superior cosmetic appearance, detection of contralateral patent processus vaginalis, low injury of the vas deferens and spermatic cord vessels, and decreased operative time [13, 14]. The laparoscopic operation for inguinal hernia can be simultaneously performed with the presence of hydrocele and lipoma of the spermatic cord or round ligament [15,16,17]. However, Alzahem did not find any clear benefit of laparoscopic herniorrhaphy over open herniorrhaphy other than reduction in MCIH development and shorter operative time in patients with bilateral hernias [18]. Other studies have shown that laparoscopic herniorrhaphy reduced recurrence and MCIH occurrence frequencies compared with open surgery for pediatric inguinal hernia repair [19,20,21].

Recurrences after pediatric or adult inguinal hernia repair are likely to occur within 2 years after surgery [9, 22,23,24,25]. There were four recurrences in the high-ligation group, all of which developed within 12 months of the first surgery; however, no recurrence was noted in the wall repair group. Note that the follow-up period was different between the two groups in this study; however, patients with recent surgery must be observed for a longer time to observe the true recurrence rate. Considering that most recurrences occurred within 12 months after surgery and that the mean follow-up period was approximately 33 months in the wall repair group. Although the follow-up period was short, the short-term outcome was significant. Nevertheless, data on more outcomes and longer follow-up periods are required to define the optimal laparoscopic procedure for indirect inguinal hernia repair because the recurrence rate can increase with time after surgery. This study compared high ligation with the wall suture technique but did not include a comparison with mesh implant surgery. A comparison of the wall repair and TAPP techniques is needed to more accurately determine surgical effectiveness; similarly, such a study with long-term follow-up is needed. Lastly, laparoscopic suturing requires experienced surgeons and has a steep learning curve.

In summary, we found that a linear suture technique without mesh implants was effective for laparoscopic herniorrhaphy for treating adolescent indirect inguinal hernias with the potential benefits of reducing recurrences. The intracorporeal suture of the myopectineal orifice may be useful for future procedures in adult patients.

References

Lichtenstein IL, Shulman AG, Amid PK, Montllor MM (1989) The tension-free hernioplasty. Am J Surg 157:188–193

Bruns NE, Glenn IC, McNinch NL, Rosen MJ, Ponsky TA (2017) Treatment of routine adolescent inguinal hernia vastly differs between pediatric surgeons and general surgeons. Surg Endosc 31:912–916

Ger R, Monroe K, Duvivier R, Mishrick A (1990) Management of indirect inguinal hernias by laparoscopic closure of the neck of the sac. Am J Surg 159:370–373

Gasior AC, Knott EM, Kanters A, St Peter SD, Ponsky TA (2015) Two-center analysis of long-term outcomes after high ligation inguinal hernia repair in adolescents. Am Surg 81:1260–1262

Esposito C, Escolino M, Cortese G, Aprea G, Turrà F, Farina A, Roberti A, Cerulo M, Settimi A (2017) Twenty-year experience with laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair in infants and children: considerations and results on 1833 hernia repairs. Surg Endosc 31:1461–1468

Kockerling F, Bittner R, Jacob DA, Seidelmann L, Keller T, Adolf D, Kraft B, Kuthe A (2015) TEP versus TAPP: comparison of the perioperative outcome in 17,587 patients with a primary unilateral inguinal hernia. Surg Endosc 29:3750–3760

Pokorny H, Klingler A, Schmid T, Fortelny R, Hollinsky C, Kawji R, Steiner E, Pernthaler H, Függer R, Scheyer M (2008) Recurrence and complications after laparoscopic versus open inguinal hernia repair: results of a prospective randomized multicenter trial. Hernia 12:385–389

Pogorelic Z, Rikalo M, Jukić M, Katić J, Jurić I, Furlan D, Budimir D, Biočić M (2017) Modified Marcy repair for indirect inguinal hernia in children: a 24-year single-center experience of 6826 pediatric patients. Surg Today 47:108–113

Shehata SM, El Batarny AM, Attia MA, El Attar AA, Shalaby AM (2015) Laparoscopic interrupted muscular arch repair in recurrent unilateral inguinal hernia among children. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 25:675–680

Reinpold W, Schroeder AD, Schroeder M, Berger C, Rohr M, Wehrenberg U (2015) Retroperitoneal anatomy of the iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal, genitofemoral, and lateral femoral cutaneous nerve: consequences for prevention and treatment of chronic inguinodynia. Hernia 19:539–548

Reddy VM, Sutton CD, Bloxham L, Garcea G, Ubhi SS, Robertson GS (2007) Laparoscopic repair of direct inguinal hernia: a new technique that reduces the development of postoperative seroma. Hernia 11:393–396

Daes J (2014) Endoscopic repair of large inguinoscrotal hernias: management of the distal sac to avoid seroma formation. Hernia 18:119–122

Bharathi RS, Arora M, Baskaran V (2008) Pediatric inguinal hernia: laparoscopic versus open surgery. JSLS 12:277–281

Lee Y, Liang J (2002) Experience with 450 cases of micro-laparoscopic herniotomy in infants and children. Pediatr Endosurg Innov Tech 6:25–28

Choi BS, Byun GY, Hwang SB, Koo BH, Lee SR (2017) A comparison between totally laparoscopic hydrocelectomy and scrotal incision hydrocelectomy with laparoscopic high ligation for pediatric cord hydrocele. Surg Endosc. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-017-5582-1

Lee SR (2017) Laparoscopic treatment of hydrocele of the Canal of Nuck in pediatric patients. Eur J Pediatr Surg. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0037-1607221

Yang XF, Liu JL (2016) Laparoscopic repair of inguinal hernia in adults. Ann Transl Med 4(20):402

Alzahem A (2011) Laparoscopic versus open inguinal herniotomy in infants and children: a meta-analysis. Pediatr Surg Int 27:605–612

Maillet OP, Garnier S, Dadure C, Bringuier S, Podevin G, Arnaud A, Linard C, Fourcade L, Ponet M, Bonnard A, Breaud J (2014) Inguinal hernia in premature boys: should we systematically explore the contralateral side? J Pediatr Surg 49:1419–1423

Yang C, Zhang H, Pu J, Mei H, Zheng L, Tong Q (2011) Laparoscopic vs open herniorrhaphy in the management of pediatric inguinal hernia: a systemic review and meta-analysis. J Pediatr Surg 46:1824–1834

Shalaby R, Ibrahem R, Shahin M, Yehya A, Abdalrazek M, Alsayaad I, Shouker MA (2012) Laparoscopic hernia repair versus open herniotomy in children: a controlled randomized study. Minim Invasive Surg 2012:484135

Collaboration EUHT (2002) Repair of groin hernia with synthetic mesh: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann Surg 235:322–332

Shalaby R, Ismail M, Gouda S, Yehya AA, Gamaan I, Ibrahim R, Hassan S, Alazab A (2015) Laparoscopic management of recurrent inguinal hernia in childhood. J Pediatr Surg 50:1903–1908

Esposito C, Montupet P (1998) Laparoscopic treatment of recurrent inguinal hernia in children. Pediatr Surg Int 14:182–184

Lee SR, Choi SB (2017) The efficacy of laparoscopic intracorporeal linear suture technique as a strategy for reducing recurrences in pediatric inguinal hernia. Hernia 21:425–433

Funding

SRL has no financial ties to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

SRL has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Damsoyu Hospital.

Human and animal rights

All procedures performed in studies human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, S.R. Benefits of laparoscopic posterior wall suture repair in treating adolescent indirect inguinal hernias. Hernia 22, 653–659 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-018-1745-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-018-1745-9