Abstract

The causes of mental disorders are multifactorial including genetic and environmental exposures, parental psychopathology being the greatest risk factor for their offspring. We set out to quantify the risk of parental psychiatric morbidity with the incidence of mental disorders among their offspring before the age of 22 years and study the sex- and age-specific associations. The present study utilises the 1987 Finnish Birth Cohort (FBC) data, which is a register-based follow-up of all 60,069 children born in Finland 1987 and followed-up until 2008. Data on psychiatric morbidity are based on inpatient care episodes of parents and both inpatient and outpatient visits of offspring and were collected from the Finnish Hospital Discharge Register which covers all Finnish citizens accessing specialized care. Altogether 7.6% of the cohort members had a parent or both parents treated at psychiatric inpatient care during the follow-up. Parental psychiatric morbidity increased the offspring’s risk for psychiatric diagnoses two to threefold versus those children without parental psychiatric hospitalization, mother’s morbidity comprising a greater risk than that of father’s. The risk was prominent for both sexes of the offspring throughout childhood and adolescence. Psychiatric disorders possess significant intergenerational continuum. It is essential to target preventive efforts on the high-risk population that comprises families with a parent or both having mental disorders. It also implies developing appropriate social and health care interventions to support the whole family.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mental disorders prevalent among young adults may originate already in childhood or adolescence [1]. The causes of mental disorders are multifactorial and no specific markers for the onset of a psychiatric disorder have been identified [2, 3]. There is, however, ample evidence showing that parental psychopathology is the greatest risk factor for their offspring psychopathology due to the increased genetic and environmental risk [4,5,6,7].

A recent meta-analysis showed the magnitude of the risk for the offspring with parental severe mental illness to be 2.5-fold to that of the control offspring [7]. When both parents were affected, the risk of mental disorder among the offspring was even higher [8]. However, it is not known how the magnitude of the risk is modified by the sex of the parent or the offspring or by the age of the child at parental hospitalization.

There are studies showing that the sex of the ill parent modifies the risk among the offspring, so that maternal psychopathology [9, 10] possesses a greater risk for offspring mental health than paternal psychopathology. However, externalizing disorders in fathers and mothers were comparably associated with offspring’s externalizing symptoms [9]. Nevertheless, in the light of few recent studies, the influence of sex in terms of parent and child seems more complicated [11,12,13,14]. Whereas Bouma et al. [15] showed girls with parental depression to be more sensitive than boys to the depressogenic effect of stressful events, Aylott et al. [11] found that mental illness in the same-sex parent did not have a significant effect on psychotic symptoms in offspring. Similarly, in parental depression and psychosis, offspring morbidity was increased due to the disorders of the opposite-sex parent [12, 13]. As a mention, depression and especially maternal depression dominate the research literature of intergenerational transmission of mental disorders and likewise, offspring sex is less frequently studied.

There are few studies about parental illness and offspring diagnosis specificity, but still no consensus whether parental psychopathology increases their offspring’s risk for mental disorders generally or is the risk diagnosis specific [for review, see 16]. There are not only studies that indicate a general risk of parental morbidity [17, 18], but also studies showing specificity, so that externalizing problems increase the risk for externalizing problems and internalizing problems associate with internalizing problems among the offspring [9].

In addition, little is known about age-specific vulnerability of the offspring. To our knowledge, no long-term follow-up from childhood to early adulthood has been made before to study the vulnerability at different developmental stages. Previous studies have concentrated on life-long effects or specific developmental stages, showing the vulnerability of adolescents due to parental psychiatric illness [15, 19], and influences of parental prenatal and postnatal depression [14, 20, 21].

Previously, we have shown that 13% of the young adults of the 1987 Finnish Birth Cohort had a mental disorder diagnosis set in the specialized care during the 21-year follow-up [22] and 14% of the cohort members had received specialized psychiatric care [23]. The females used significantly more specialized psychiatric outpatient services than the males, whereas there was no statistical difference between sexes as regards psychiatric inpatient care. Median ages as regards the first instance of specialized psychiatric care as an inpatient were 12 years for males and 15 years for females [23].

The basis of Finnish health services and the first point of entry is primary health care. Most children and adolescents in Finland use public services through child and school health services, which are provided by the municipalities for all children and adolescents free of charge. The access to specialized services needs a referral from primary health care. However, most children and adolescents in Finland are referred to specialists in psychiatric matters, and e.g. between 1994 and 2008, outpatient visits to specialized child psychiatric care units almost tripled, and the number of people treated in adolescent psychiatric care almost quadrupled in Finland [24]. Still, we know that mental health problems in children and adolescents, as well as in adults, consequently remain unrecognized and untreated [25,26,27].

In many previous studies, data on different types of childhood adversities have been collected via questionnaires or interviews in retrospect, which predisposes to recall bias concerning both own [28] or parental symptoms [29]. In the present study, we set out to study the association of parental psychiatric morbidity with the prevalence of mental disorders among their offspring before the age of 22 years in a national level using longitudinal register-based cohort data of one total age cohort to avoid selection and recall bias. In the present study, we aimed to quantify the risk of offspring mental disorders and to examine the associations by sex of the parent or the child or the age of the child at parental hospitalization. This knowledge is needed for enhancing adolescents’ mental health and for targeting preventive interventions.

Subjects and methods

The present study utilises the 1987 Finnish Birth Cohort (FBC) data [30], which is a register-based follow-up of all 60,069 children born in Finland 1987 and followed-up until 2008 (21 years). The analyses were based on all children surviving infancy (n = 59,476). The study obtained ethics approval of the National Institute for Health and Welfare Ethical committee §28/2009.

The Finnish Hospital Discharge Register (HDR) includes all inpatient care episodes from all Finnish hospitals since 1969 and all specialised level outpatient visits in public hospitals since 1998 [31]. Data on psychiatric morbidity are based on inpatient care episodes of biological parents and both inpatient and outpatient visits of offspring with no minimal age for referral for specialized psychiatric care. Data on psychiatric diagnoses of the cohort members were collected from all specialised care visits and reported using the International classification of diseases (ICD) codes 290–319 between 1987 and 1995 and codes F01–F99 since 1996. Data on parental psychiatric morbidity were collected from the HDR and used to identify cohort members’ parents with psychiatric inpatient care between January 1, 1987 and December 31, 2008. The fact that the parents were treated in hospitals implies that they suffered from severe psychiatric disorders that have needed inpatient care. The children’s age at the time of parental first psychiatric hospitalization after children’s birth was determined and the cohort grouped according to the age: 0–6 years (early years), 7–12 years (childhood), 13–17 years (teen age), and 18–21 years (early adulthood).

The children’s psychiatric diagnoses were grouped according to ICD-10 classification. The cohort members with mental disorders due to known physiological conditions (F01–09) or intellectual disabilities (F70–79) were left out from the further analyses because of the very limited number of the cases F01–09 (N = 32), and F70–79 because of the distinct etiology of these disorders compared with other mental disorders. ICD-10 codes used are based on medical classification list by the World Health Organization (WHO) as follows:

- F01–F09:

-

Mental disorders due to known physiological conditions.

- F10–F19:

-

Mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use.

- F20–F29:

-

Schizophrenia, schizotypal, delusional, and other non-mood psychotic disorders.

- F30–F39:

-

Mood [affective] disorders.

- F40–F48:

-

Anxiety, dissociative, stress-related, somatoform and other nonpsychotic mental disorders.

- F50–F59:

-

Behavioral syndromes associated with physiological disturbances and physical factors.

- F60–F69:

-

Disorders of adult personality and behaviour.

- F70–F79:

-

Intellectual disabilities.

- F80–F89:

-

Pervasive and specific developmental disorders.

- F90–F98:

-

Behavioral and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence.

- F99:

-

Unspecified mental disorder.

The register data were combined using the encrypted personal identification numbers of the children and their parents.

Logistic regression analyses were used to define the odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for mental disorders according to parental psychiatric morbidity. The analyses were performed separately according to the sex of the parent and the child and the age of the child at parental hospitalization. The risk for offspring’s specific psychiatric diagnoses according to parental psychiatric illness was determined by comparing the cohort members with parental illness with the cohort members not having a parent with psychiatric hospitalization. The age-specific risks were determined by comparing the affected group with those having no parental hospitalization at any time during the 21-year follow-up. 7% of the cohort members’ diagnoses were prior to parental hospitalization. Statistical differences were determined with two-proportions z test.

The data analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics version 25 (IBM Corp. Released 2017. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp).

Results

Prevalence of offspring psychiatric diagnoses according to parental psychiatric morbidity

Based on the information from the Finnish HDR over the 21-year follow-up from 1987 to 2008, altogether 7578 (12.7%) out of 59,476 children from the 1987 FBC had received a psychiatric diagnosis (F in ICD-10); girls (14.2%) more often than boys (11.4%). Altogether, 7.6% (4495) of the cohort members had a parent or both parents treated at psychiatric inpatient care during the follow-up. 4.3% (1295) of the boys and 4.3% (1253) of the girls had a father treated at inpatient care and 3.6% (1091) of the boys and 3.6% (1047) of the girls had a mother treated at inpatient care, 199 cohort members (0.3%) had both parents treated.

Figure 1 shows the prevalence of offspring psychiatric diagnoses (ICD-10 codes F10–F98) by parental psychiatric morbidity. Overall, psychiatric diagnoses were twice more common among children with parental mental disorder (23.8%), and three times more common if both parents had mental disorder (34.7%) than among the offspring without parental psychiatric hospitalization (12.1%). Similarly, the prevalence of offspring’s all specific psychiatric diagnoses, except F50–59, was significantly higher (p < 0.001) when either parent had had psychiatric illness compared to no parental illness. The prevalence was the highest if both parents had been hospitalized. Any psychiatric diagnosis, and specifically mood (F30–39), neurotic, stress-related and somatoform (F40–48) and behavioural and emotional disorders (F90–98) among the offspring were significantly more common if mother had suffered from psychiatric illness compared to that of fathers.

Prevalence of children’s psychiatric diagnosis (%) according to parental mental disorder. *Statistical differences between the prevalence of the offspring with no parental psychiatric illness compared to the offspring having either parent with psychiatric illness, and the offspring with maternal illness compared to the paternal psychiatric illness are shown in the figure with brackets, respectively, and the statistical significances are marked with p values

Sex- and diagnosis specificity

Table 1 shows that 30.2% of the girls and 24.0% of the boys with maternal psychiatric illness had been diagnosed with a mental disorder before 22 years of age, whereas 13.8% of the girls and 11.1% of the boys without maternal psychiatric disorder had received such a diagnosis. Similarly, 24.3% of the girls and 19.8% of the boys with paternal psychiatric disorder had the diagnosis, whereas 14.0% of the girls and 11.2% of the boys without paternal diagnosis were diagnosed during the follow-up.

The frequencies of all other psychiatric diagnoses except behavioural syndromes associated with physiological disturbances and physical factors (F50–59) and pervasive and specific developmental disorders (F80–89) for boys were significantly higher among the offspring of the mothers with psychiatric illness compared to the cohort members with no maternal illness. Likewise, all other diagnoses except F50–59 for both sexes were significantly more common when father had suffered from psychiatric illness.

In general, the offspring had mental disorder more often when mother had suffered from a psychiatric illness than when father was the affected one. More specifically, mood (F30–39) disorders and among girls, behavioural and emotional disorders (F90–98), and among boys, schizophrenia group disorders (F20–29) were significantly more common if mother had had a psychiatric illness compared to that of fathers.

Figure 2 shows the odds ratios for children’s psychiatric diagnoses according to their parental mental disorder during the entire follow-up until the age of 22 years. Parental psychiatric illness possessed the increased risk for schizophrenia group disorders (F20–29), mood disorders (F30–39), neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders (F40–48), substance abuse disorders (F10–F19), disorders of adult personality and behaviour (F60–69) and behavioural and emotional disorders (F90–98) among their offspring. Only the risk for behavioural syndromes associated with physiological disturbances and physical factors (F50–59) was not increased, and pervasive and specific developmental disorders (F80–89) by maternal morbidity among boys.

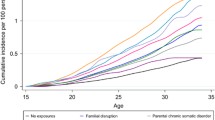

Timing of the first parental psychiatric hospitalization

During the whole 21-year follow-up, the odds ratios were higher for boys (OR 2.5) and girls (OR 2.7) when the mother had been hospitalized compared to when the father had been hospitalized (OR 2.0 for boys and girls) (Table 2). Parental hospitalization at children’s teen years showed significant sex specificity. The risk for the offspring was significantly higher (3.1–3.5) when mother had been hospitalized during children’s teen years compared to the paternal illness (OR 1.6–2.0). In contrast, paternal illness tended to possess higher risk the younger their sons. For the daughters, the risk was twofold irrespective of the timing of the hospitalization. The odds ratio for specific age group was determined by comparing the group with those having no parental diagnosis at any time during the 21-year follow-up.

Supplement Tables 1–4 show the risks for children’s specific mental diagnoses at 0–21 years according to the children’s age at the time of the parental hospitalization.

Maternal hospitalization before the children’s school age (under 7 years) increased the likelihood of all other specific diagnoses except F50–59 and F80–89 for boys over twofold (ORs 2.1–5.4) among the offspring (Supplement Tables 1 and 2). When at 7–12 years, maternal psychiatric morbidity increased the risk for specific diagnoses (F20–29, F30–39, F40–49, F90–98 and F10–19 for boys) two to threefold (ORs 2.1–3.3). The ORs were mostly highest, 2.9–3.7 for girls and 2.0–5.3 for boys if maternal psychiatric hospitalization took place at offspring’s teen years. In contrast, in terms of fathers’ hospitalization, the risks tended to be higher before teen years and for boys, especially under 7 years (Supplement Tables 3 and 4).

Discussion

This register-based study reports the association of parental psychiatric morbidity on their children’s mental disorders in different diagnostic groups at a national level using comprehensive longitudinal follow-up data. The results show clearly that any parental psychiatric disorder that has been severe with need for psychiatric inpatient treatment increases the children’s risk of mental disorders. Our study extends previous results showing the intergenerational transmission of parental mental health problems [6, 7, 17, 32, 33], but brings also new information of the diagnosis-, sex- and age-specific outcomes until early adulthood. This knowledge is needed for further preventing mental disorders.

Altogether, mental disorders were twice more common among children with parental psychiatric illness and three times more common if both parents have been treated in psychiatric inpatient care than among children without parental hospitalization. These results confirm the previous studies of the magnitude of the risk of parental psychopathology for their offspring [7, 8].

In general, parental psychiatric disorder comprises the risk for all offspring diagnoses, except behavioural syndromes associated with physiological disturbances and physical factors. The offspring’s specific diagnoses show a typical sex-specific pattern of the mental disorders and are in consistence with our previous results of the psychiatric morbidity [22]. Our results support the idea of general risk of parental morbidity for their offspring [17], and we conclude, that parental psychiatric illness increases the offspring risk for mental disorders with little specificity.

However, we found sex specificity in this intergenerational transmission of psychiatric disorders. The results indicate that maternal illness possesses higher risk for the offspring than paternal illness, which is in consistence with earlier studies [9, 10]. All the same, the results also confirm the earlier findings of the offspring’s increased risk due to father’s psychiatric illness [20]. No evidence of parental morbidity affecting only the offspring of specific sex was seen in this study. Any psychiatric diagnosis, and, specifically, mood, neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders and behavioural and emotional disorders were significantly more common among the offspring if mother had suffered from psychiatric illness compared to father’s morbidity. In more detail, when mother was hospitalized, girls suffered from mood and behavioural and emotional disorders and boys from mood and schizophrenia group disorders more than when father was the one treated in psychiatric care. It must be pointed out that the registers contain only information on biological parents, so the influence of family breakdown and reduced likelihood of the biological father living with the child compared to the biological mother cannot be excluded and this may partly explain the stronger association between mother’s illness to offspring disorders.

The sex specificity seen in our study may also be due to different parental morbidity affecting the offspring differently. Women suffer more from internalizing psychiatric outcomes, e.g. severe depression and men have more external psychiatric outcomes. It is known that maternal depression increases the stress in the whole family [34] and also predisposes the child for mothers’ negative cognition, critical or over-custodial behaviour or affect [35], which may increase the children’s vulnerability for mental problems.

In consistence with previous results [15, 19, 21, 36], we also found evidence that the vulnerability may be related to age. Although the risk is high at every stage of the development from childhood to early adulthood, both sexes showed increased risk for maternal morbidity at their teens. This may indicate an important age-specific vulnerability which should be considered when planning preventive efforts for offspring wellbeing. It is known that parental illness at teen years may additionally lead to harmful social consequences, which may increase offspring’s mental problems as such. However, the results should be interpreted with caution as hospitalization of a parent may occur after several years of suffering, and some offspring is affected by parental illness at all stages of development. In this study, we could not exclude the effects of offspring mental illness on parental morbidity, which may affect the results leading to overestimation of the intergenerational transmission. The results concerning the offspring’s teen age vulnerability for mother’s morbidity may be partly explained by the offspring’s increased psychiatric diagnoses at their teens, if we assume that mothers are more vulnerable for their adolescent’s mental problems than fathers. It is known that parents, especially mothers, may have difficulties in adjusting for challenging times in child’s development, such as teen years and this increases vulnerability for depression [37]. However, in this study, the associations between parental hospitalization and offspring mental disorders were strong and can only partially be explained by the offspring’s morbidity.

The limitation of this register-based study is that we concentrated solely on hospital treated psychiatric morbidity. This restricts the generalizability of the results to having a parent with less severe mental disorders. This also means that certain disorders are likely to be underreported (e.g. anxiety, depression). One may think that parental severe psychiatric illness possesses a more prominent risk for their offspring than non-severe conditions due to increased genetic and social burden, e.g. poverty, familial stress and disruptions [38]. This aspect is supported by a recent study, which found the offspring mental disorder prevalence to be the highest when primary carer had comorbid or more severe disorders [6]. On the other hand, at times of severe illness, intensive care is permitted which may be good for the whole family. In addition, parenthood predictability is crucial for children’s wellbeing and if parent suffers, not from severe illness, but from psychiatric symptoms, that affect one’s behaviour, the risk for the children could be even more harmful. Parental psychopathology has been associated with both withdrawn and intrusive parental behaviour and insensitive parenting, particularly neglectful or abusive caregiving [for review, see e.g. 39]. The severity of the illness and different parental morbidity should be addressed in the future studies.

To our knowledge, this is the first study in which both the sex of the affected parent and the offspring and the timing of parental psychiatric morbidity were analysed at the same setting with the long-term follow-up. The main strength of our study is that it involves a complete census of all infants born in a single year in Finland and followed-up until early adulthood, thus providing representative information about later mental disorders during the development to early adulthood. It is well-known that mental disorders often emerge in late adolescence or early adulthood, even though their roots may go back to childhood [e.g. 39]. The data of this longitudinal study are based on Finnish hospital discharge register, which covers all Finnish inhabitants treated at specialized care. Thus, the data are not biased by background variables or the factors involved with retrospective interviews. All Finnish citizens and permanent residents are entitled to health care, which is heavily subsidized.

Moreover, we did not consider any other adversities that may have also affected children’s mental wellbeing. Although the accumulation of different adversities may comprise the most crucial risk for the children’s psychiatric wellbeing [e.g. 3, 40], earlier studies [e.g. 22, 39, 41] show that parental psychiatric morbidity is an independent and notable risk factor for the children’s favourable development of mental health. Having a parent with severe hospital treated mental disorder may also associate with reduced resilience against other life stressors [19].

Another limitation is that the psychiatric diagnoses were based on the use of specialized health care only. Accordingly, those cohort members with mental problems who have received care only from the primary care or received no care at all are missing from the analyses. However, in Finland, practically all children and adolescents are referred to specialized care in case of mental health issues. The offspring in our study were 21 years old when the follow-up ended. In our data, a longer follow-up was not available for examining the specific effects of parental psychiatric disorders on the mental disorders that emerge around and after the age of 21, such as schizophrenia and mood disorders. The transition to adulthood might, therefore, lead to even more diagnoses. Moreover, we did not examine the effect of specific parental diagnoses but concentrated generally on the association of any parental psychiatric hospitalization on the children’s psychiatric morbidity. Nevertheless, previous studies have shown that virtually all parent disorders were associated with offspring disorders with little specificity [4, 11, 42].

In conclusion, our results show significant intergenerational transmission of psychiatric disorders, and parental psychiatric morbidity comprises a substantial risk for the offspring mental health. Parental psychiatric morbidity increased the offspring’s risk for psychiatric diagnoses two to threefold versus those children without parental psychiatric hospitalization, mothers’ morbidity associating with a greater risk than that of fathers. The risk was high through childhood to early adulthood and most prominent when mother was hospitalized at the offspring’s teens. Based on these register data, we do not know the developmental trajectories of this genetically and environmentally determined course. Our results support previous results on the need of screening and targeting preventive efforts on the high-risk population that comprises families with a parent or both having mental disorders [43]. It also implies developing appropriate social and health care interventions to support the whole family.

References

Kessler RC, Davis CG, Kendler KS (1997) Childhood adversity and adult psychiatric disorder in the US National Comorbidity Study. Psychol Med 27:1101–1119

Pirkola S, Isometsä E, Aro H, Kestilä L, Hämäläinen J, Veijola J et al (2005) Childhood adversities as risk factors for adult mental disorders. Results from the Health 2000 study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 40:769–777

Greif Green J, McLaughlin KA, Berglund PA, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM et al (2010) Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbility Survey Replication I. Arch Gen Psychiatry 67:113–123

McLaughlin KA, Gadermann AM, Hwang I, Sampson NA, Al-Hamzawi A, Andrade LH et al (2012) Parent psychopathology and offspring mental disorders: results from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Br J Psychiatry 200:290–299

D’Onofrio BM, Slutske WS, Turkheimer E, Emery RE, Harden KP, Heath AC et al (2007) Intergenerational transmission of childhood conduct problems. A children of twins study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64:820–829

Johnson SE, Lawrence D, Perales F, Baxter J, Zubrick SR (2018) Prevalence of mental disorders among children and adolescents of parents with self-reported mental health problems. Community Ment Health J 54:884–897

Rasic D, Hajek T, Alda M, Uher R (2014) Risk of mental illness in offspring of parents with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of family high-risk studies. Schizophr Bull 40:28–38

Gottesman II, Laursen TM, Bertelsen A, Mortensen PB (2010) Severe mental disorders in offspring with 2 psychiatrically ill parents. Arch Gen Psychiatry 67:252–257

Connell AM, Goodman SH (2002) The association between psychopathology in fathers versus mothers and children’s internalizing and externalizing behavior problems: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 128:746–773

Malmberg L-E, Flouri E (2011) The comparison and interdependence of maternal and paternal influences on young children’s behavior and resilience. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 40:434–444

Aylott A, Zwicker A, MacKenzie LE, Cumby J, Propper L, Abidi S et al (2019) Like father like daughter: sex-specific parent-of-origin effects in the transmission of liability for psychotic symptoms to offspring. J Dev Orig Health Dis 10:100–107

Goldstein JM, Cherkerzian S, Seidman LJ, Petryshen TL, Fitzmaurice G, Tsuang MT, Buka SL (2011) Sex-specific rates of transmission of psychosis in the New England high-risk family study. Schizophr Res 128:150–155

Nomura Y, Warner V, Wickramaratne P (2001) Parents concordant for major depressive disorder and the effect of psychopathology in offspring. Psychol Med 31:1211–1222

Gutierrez-Galve L, Stein A, Hanington L, Heron J, Ramchandani P (2015) Paternal depression in the postnatal period and child development: mediators and moderators. Pediatrics 135:2014–2411

Bouma E, Ormel J, Verhulst F, Oldehinkel A (2008) Stressful life events and depressive problems in early adolescent boys and girls: the influence of parental depression, temperament and family environment. J Affect Disord 105:185–193

van Santvoort F, Hosman CM, Janssens JM, van Doesum KT, Reupert A, van Loon LM (2015) The impact of various parental mental disorders on children's diagnoses: a systematic review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 18:281–299

Dean K, Stevens H, Mortensen PB, Murray RM, Walsh E, Pedersen CB (2010) Full spectrum of psychiatric outcomes among offspring with parental history of mental disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 67:822–829

Ramchandani P, Psychogiou L (2009) Paternal psychiatric disorders and children’s psychosocial development. Lancet 374(9690):646–653

Gershon A, Hayward C, Schraedley-Desmond P, Rudolph KD, Booster GD, Gotlib IH (2011) Life stress and first onset of psychiatric disorders in daughters of depressed mothers. J Psychiatr Res 45:855–862

Psychogiou L, Moberly NJ, Parry E, Nath S, Kallitsoglou A, Russell G (2017) Parental depressive symptoms, children’s emotional and behavioural problems, and parents’ expressed emotion-critical and positive comments. PLoS ONE 12(10):e0183546

Fletcher RJ, Feeman E, Garfield C, Vimpani G (2011) The effects of early paternal depression on children's development. Med J Aust 195:685–689

Paananen R, Ristikari T, Merikukka M, Gissler M (2013) Social determinants of mental health: a Finnish nationwide follow-up study on mental disorders. J Epidemiol Commun Health 67:1025–1031

Paananen R, Santalahti P, Merikukka M, Rämö A, Wahlbeck K, Gissler M (2013) Socioeconomic and regional aspects in the use of specialized psychiatric care—a Finnish nationwide follow-up study. Eur J Public Health 23:372–377

Saukkonen S (2009) Special health care and mental health care 2008. Statistical report/Terveyden ja hyvinvoinnin laitos (THL):200924/2009. http://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi-fe201205085018. Accessed 1 Apr 2020

Tick NT, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC (2008) Ten-year increase in service use in the Dutch population. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 17:373–380

Zwaanswijk M, Verhaak PF, Bensing JM, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC (2003) Help seeking for emotional and behavioural problems in children and adolescents: a review of recent literature. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 12:153–161

Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, Gasquet I, Kovess V, Lepine JP et al (2004) Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA 291:2581–2590

Patten SB, Williams VA, Lavorato DH, Bulloch AGM, D’Arcy C, Streiner DL (2012) Recall of recent and more remote depressive episodes in a prospective cohort study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 47:691–696

Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Taylor A, Kokaua J, Milne BJ, Polanczyk G, Poulton R (2010) How common are common mental disorders? Evidence that lifetime prevalence rates are doubled by prospective versus retrospective ascertainment. Psychol Med 40:899–909

Paananen R, Gissler M (2012) Cohort profile: the 1987 Finnish Birth Cohort. Int J Epidemiol 41:941–945

Gissler M, Haukka J (2004) Finnish health and social welfare registers in epidemiological research. Norsk Epidemiologi 14:113–120

Beardslee WR, Versage EM, Gladstone TR (1998) Children of affectively ill parents: a review of the past 10 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 37:1134–1141

Beardslee WR, Gladstone TR, O'Connor EE (2011) Transmission and prevention of mood disorders among children of affectively ill parents: a review. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 50:1098–1109

Burke L (2003) The impact of maternal depression on familial relationships. Int Rev Psychiatr 15:243–255

Elgar FJ, McGrath PJ, Waschbusch DA, Stewart SH, Curtis LJ (2004) Mutual influences on maternal depression and child adjustment problems. Clin Psychol Rev 24:441–459

Nath S, Russell G, Kuyken W, Psychogiou L, Ford T (2016) Does father-child conflict mediate the association between fathers' postnatal depressive symptoms and children's adjustment problems at 7 years old? Psychol Med 46:1719–1733

Allen JP, Manning N, Meyer J (2010) Tightly linked systems: reciprocal relations between maternal depressive symptoms and maternal reports of adolescent externalizing behavior. J Abnorm Psychol 119:825–835

Appleyard K, Egeland B, van Dulmen MH, Sroufe LA (2005) When more is not better: the role of cumulative risk in child behavior outcomes. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 46(3):235–245

Fryers T, Brugha T (2013) Childhood determinants of adult psychiatric disorder. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health 9:1–50

McGrath JJ, McLaughlin KA, Saha S, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Al-Hamzawi A, Alonso J et al (2017) The association between childhood adversities and subsequent first onset of psychotic experiences: a cross-national analysis of 23 998 respondents from 17 countries. Psychol Med 47:1230–1245

Solantaus T, Paavonen EJ (2009) Impact of parents' mental health disorders on psychiatric problems of the offspring (Article in Finnish). Duodecim 125:1839–1844

Zwicker A, MacKenzie LE, Drobinin V, Howes Vallis E, Patterson VC, Stephens M et al (2019) Basic symptoms in offspring of parents with mood and psychotic disorders. BJPsych Open 5(4):e54

Maciejewski D, Hillegers M, Penninx B (2018) Offspring of parents with mood disorders: time for more transgenerational research, screening and preventive intervention for this high-risk population. Curr Opin Psychiatry 31:349–357

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The study obtained ethics approval of the Ethical committee at the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare §28/2009 and have therefore been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Paananen, R., Tuulio-Henriksson, A., Merikukka, M. et al. Intergenerational transmission of psychiatric disorders: the 1987 Finnish Birth Cohort study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 30, 381–389 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01524-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01524-5