Abstract

This study aimed to disentangle time-stable and time-varying effects of maternal and paternal depression on trajectories of adolescent depression from ages 13 to 23 and examined whether self-esteem moderates the examined associations. Sex differences in the direct effects of parental depression and its interacted effects with self-esteem were further explored. Data were collected from a sample of 2502 adolescents and their parents participating in a panel study spanning from the year 2000 to 2009 in northern Taiwan. Multilevel modeling was conducted to disentangle the time-stable and time-varying effects of parental depression on adolescent depression. The moderating role of self-esteem and the potential sex differences in the transmission process were tested by adding two- and three-way interactions among parental depression, self-esteem, and sex of adolescents in the models. As predicted, significant time-stable intergenerational transmission of depression was found, indicating that adolescents of parents with higher levels of depression were at increased risks for depression. Self-esteem was further found to buffer the negative effects of maternal depression on development of depression in offspring. No sex-specific intergenerational transmission of depression was observed. In sum, both maternal and paternal depression contributed to elevated levels of adolescent depression. The effects of maternal depression, however, may not be uniform, but depend on levels of self-esteem. Intervention and prevention strategies that enhance self-esteem may help participants withstand the negative effects of maternal depression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Depression is an important contributor to disability around the world [1], with high prevalence in both adult [2] and adolescent populations [3]. Depression has also been linked to several negative health and behavioral outcomes, including obesity [4], substance use [5], and antisocial behavior [5]. The onset of depression often begins during adolescence and could be chronic and recurrent throughout the individual’s life-span [3]. Developmental research further shows a significant upsurge in rates of depression in adolescence [6], making identification for the causes and etiology of depression in youth a public health priority.

One of the important risk factors of adolescent depression is parental depression. The transmitted process of depression across generations has been recognized such that parental depression contributes to increased risk of psychopathology in offspring [7]. Specifically, research has found that offspring of depressed parents are at an elevated risk for a variety of psychopathology throughout their life-span [7, 8]. During childhood, higher parental depression predicted greater risks of internalizing symptoms among children [9]. The negative effects of parental depression on offspring depression were also observed during adolescence [10]. Research also found that the impacts of parental depression may last through adulthood and result in negative influences on adults’ health outcomes [11], even when their parents have recovered [12].

Despite considerable research demonstrating the effects of parental depression on risk for depression in offspring, important gaps in the field remain. First, most previous research is cross-sectional [13] or only examined the short-term influences of parental depression using two or three-time points of data [14, 15], without disentangling the time-varying and time-stable effects of parental depression. Informed by prior research [16], the time-stable effects reflect the average levels of parents’ depression across times that influence adolescent depression during the same period of time and can provide “who” is at risk for depressive symptoms. In contrast, time-varying effects suggest the risk factors for “when” risk is elevated. However, most current research focuses exclusively on testing a severity hypothesis, addressing the question of whether adolescents who have depressive parents are more likely to have higher levels of depression than those who do not have depressive parents. The lack of research on “when” adolescents are at risk prevents us from timely intervention to decrease the risk of depression. Supporting the views of time-varying effects, Flouri et al. [17] showed that time-varying effects of maternal depression predicted both initial and levels of internalizing problems in a sample of 17,160 children. Similarly, in understanding the association between parental depression and children’s externalizing outcomes, Brammer et al. [18] found that children whose parents reported increasing patterns of depression over time demonstrated higher levels of oppositional defiant disorder. Since the influences of parental depression may change over the course of adolescent development, incorporating the time domain in understanding the intergenerational transmission of depression can provide valuable information for intervention and prevention efforts. However, research that simultaneously examines both the time-stable and time-varying effects of parental depression on adolescent depression is still limited.

Another gap in the literature is that only a few studies have investigated the protective factors that help adolescents withstand the negative effects of parental depression. Research has found that the association between parental depression and youth problems is not the same for all families [19, 20], indicating the existence of factors that may moderate the risks of parental depression on adolescent health outcomes. Across studies examining moderators in the intergenerational transmission of depression, one factor that has received little attention is self-esteem, which is defined as an individual’s conscious feeling of self-worth and acceptance [21]. Based on the self-esteem theory of depression [22], a positive view of the self helps to buffer the risks of stressful events on depression. Specifically, adolescents with high self-esteem may have more psychological resources than do those with low self-esteem to help ameliorate their depressive symptoms associated with stressful events such as parental depression. Empirical evidence also supports the views that individuals’ personal characteristics, such as self-esteem, are stress-protective [23,24,25]. For example, in a sample of 238 children and adolescents aged between 8 and 16 years, self-esteem acted as a buffer in the association between negative life events and psychological symptoms [23]. Similarly, Tobia et al. [24] found that children with higher levels of self-esteem performed better on cognitive performance following social exclusion. No study, however, has ever tested the buffering role of self-esteem in the intergenerational transmission of depression.

The current study

To fill the gaps in the literature, this study aims to extend previous research on intergenerational transmission of depression by examining (1) the effects of time-stable and time-varying parental depression on offspring depression from adolescence to young adulthood, and (2) the moderating role of self-esteem in the association between parental depression and adolescent depression. In addition, because some studies have observed sex differences in the manifestation, prevalence, and risk factors of depression [26, 27], we also examined the sex differences in the main effects of parental depression and the moderated effects of self-esteem on adolescent depression. Due to the potential sex-dependent effects of parental depression on adolescent health outcomes [28,29,30,31], we further considered the interaction between the sex of the parent and that of the adolescent in the observed associations by examining the effects of parental depression separately for mothers and fathers.

We hypothesized that adolescents of parents with higher average levels of depression (i.e., time-stable effects of depression) during the study period would have elevated levels of depression during the same period of time. Similarly, we hypothesized that adolescents of parents who demonstrated episodic spikes in depression (i.e., time-varying effects of depression) would show increased levels of depression. Regarding the moderating effects of self-esteem, we hypothesized that the effects of time-stable and time-varying effects of parental depression on adolescent depression would be buffered by self-esteem such that the effects of parental depression on adolescent depression would be weaker for adolescents with higher levels of self-esteem than those with lower levels of self-esteem. In addition, research has suggested that females may be more vulnerable to the negative effects of stressful interpersonal events (e.g., parental depression) [32] as they value interpersonal intimacy more than males do due to the influences of gender-specific socialization processes. Therefore, we further hypothesized that the extent of intergenerational transmission of depression would be more evident in females than in males, and that adolescent depression would be more affected by their same-sex parent’s depression [28,29,30,31], particularly in the presence of low self-esteem.

Methods

Data and sample

Data were obtained from the Taiwan Youth Project (TYP), conducted by the Institute of Sociology, Academia Sinica, Taiwan. The TYP is a longitudinal study spanning from the year 2000 to 2009 to investigate the trajectories of adolescent health and health behavior as well as risk and protective factors from different domains of life, including individual, family, school, and neighborhood domains. Multistage stratified sampling was used to select two student cohorts from northern Taiwan: seventh graders (Junior 1 sample) and ninth graders (Junior 3 sample). Baseline data were collected in schools with self-administrated questionnaires. Nine waves of data were collected for the Junior 1 sample and eight waves of data were collected for the Junior 3 sample. To maintain confidentiality and fidelity, trained data collectors were asked to follow a written protocol for describing the study, obtaining assent, and giving instructions for completing questionnaires. Before the survey was administered, each student completed a written consent form. In addition, TYP also conducted five waves of parent surveys that corresponded with Waves 1, 3, 6, 8, and 9 of the school-based data collections for the Junior 1 sample. For the Junior 3 sample, parent surveys were conducted in Waves 1, 4, 6, and 7.

For the current study, the data mainly came from the Waves 1, 3, 6, 8, and 9 of the TYP study for the Junior 1 sample and their parents because more waves were collected for this sample and because our time-varying study variables (i.e., adolescent depression and self-esteem) were only available for this sample at each of the five selected waves. Response rates ranged between 64.50 and 99.80% during the study period. Our analytical sample included adolescents who were 13–14 years old in Wave 1, participated in at least two waves, and have parent data for at least one wave of data collection, resulting in a total study sample of 2502 adolescents. Of those in the analysis sample, 47.80% (n = 1196) participated in all five waves and 23.54% (n = 589), 14.27% (n = 357), and 14.39% (n = 360) participated only in four, three, and two waves, respectively. Models for maternal effects used data from all adolescents who ever have data about their mother (n = 2032) and models for paternal effects used data from all adolescents who had data about their father (n = 997). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Taiwan University Hospital (201807007RINA).

Measures

Adolescent depression

In each wave, 16 items from the short version of the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R) [33] were used to assess whether adolescents had experienced certain depressive symptoms (e.g., loneliness, depressed mood, insomnia, numbness in some parts of the body, and feeling as if something is sticking to your throat) and how serious the experience was in the past week. The response options ranged from 1 = never to 5 = yes, very serious. The 16 items were averaged to create a depression score, with a higher score indicating a higher level of adolescent depression. The measure of adolescent depression in the current study had a good reliability with an average Cronbach's α of 0.88 across waves.

Parental depression

Parental depression was measured using 11 items from the short version of the SCL-90-Reversed [33]. At each wave, either mother or father self-reported whether they had experienced various depressive symptoms during the past weeks. The items were assessed based on a five-point Likert scale (1 = never to 5 = yes, very serious). Scores were calculated by averaging the 11 items, with higher scores indicating higher levels of parental depression. The average Cronbach's α for parental depression across waves in the study sample was 0.89.

Self-esteem

Six items adapted from the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale [21] were used to assess adolescent self-esteem. In each wave, adolescents were asked to indicate the degree of agreement with the following statements: (1) I cannot solve some of my problems; (2) I cannot control what happens to me; (3) I have a positive attitude toward myself; (4) I am satisfied with myself; (5) I certainly feel useless at times; and (6) at times I think I am no good at all. The responses were measured on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = strongly agree to 4 = strongly disagree. Items were averaged after appropriate reverse coding to reflect levels of self-esteem, with higher scores indicating higher self-esteem. In the current study, the measure of self-esteem had an acceptable reliability with an average Cronbach's α of 0.74 across waves.

Covariates

The biological sex of adolescents was self-reported and was coded such that 1 = males and 2 = females. Age was calculated based on the adolescents’ self-reported data for the date of birth at each wave and was coded in years. The education of fathers and mothers were assessed using adolescents’ reports of the highest level of education attained by their parents across waves and was coded such that 0 = junior high and below, 1 = senior high school, and 2 = college and above. Family structure was assessed based on parents’ reports of their current marital status and living arrangements across waves and was coded such that 1 = single-parent household and 0 = two-parent household. Family income was measured based on parents’ reports of monthly household income across waves and was coded such that 0 = less than or equal to $29,999 New Taiwan Dollars (TWD), 1 = from TWD 30,000 to TWD 59,999, 2 = from TWD 60,000 to TWD 89,999, and 3 = more than or equal to TWD 90,000. During the study period, 1 US dollar was about TWD 33.

Data analysis

Data analysis involved three phases: imputation of missing data, estimation of longitudinal trajectories of adolescent depression, and hypothesis testing. First, the issue of missing data was addressed through multiple imputations using SAS PROC MI [34]. All covariates had rates of missingness between 0 and 34% across all waves and were assumed to be missing at random. The patterns of missing data were examined by conducting an attrition analysis [35]. We used logistic regression to predict study dropout (coded as “one” for adolescents who did not participate at one or more waves and “zero” for adolescents who participate in all waves). Adolescents with one and more waves of dropout were more likely from families with less educational attainment, from families with higher incomes, or whose parents had reported higher levels of depression at baseline. Ten sets of missing values were imputed using multiple-chain Markov Chain Monte Carlo methods. Models were fitted to each of the 10 imputed datasets and the parameter estimates were combined using SAS PROC MIANALYZE [34].

Next, the optimal unconditional growth curve model of adolescent depression was determined by using age as the primary metric of time to estimate the average trajectory of adolescent depression from ages 13 to 23. The optimal unconditional model was determined by examining and comparing the functional form of the trajectories (i.e., flat, linear, and quadratic) as well as specifying the random effects structure. The best-fitting unconditional model of adolescent depression was a quadratic model with a heteroscedastic error structure and included two random effects (individual random intercept and individual random slope). All variables were then centered appropriately before hypothesis testing. Specifically, time-varying parental depression scores were person-mean centered (i.e., by subtracting the person-specific mean of the parental depression scores from each of that person's score at each wave such that they represented fluctuations from one's average level) and time-stable parental depression scores were grand-mean centered (i.e., by subtracting the mean for the sample from each individual's score averaged across the study period to represent average effects of parental depression across the study period) [36]. In addition, a time-varying moderator (i.e., self-esteem) was person-mean centered and all other time-stable variables (parental education, family structure, and family income) were grand-mean centered.

Finally, a series of conditional multilevel models were conducted to test study hypotheses with separate analyses for mothers and fathers. Model building proceeded as follows: first, we estimated the main effects of time-stable parental depression, the time-varying spike in parental depression, and self-esteem on development of adolescent depression. Next, we tested our moderation hypothesis by including interactions between self-esteem and parental depression (self-esteem time-stable parental depression and self-esteem time-varying parental depression). Finally, to examine potential sex differences, we added two- and three-way interactions among sex, self-esteem, and parental depression measures: (1) sex × self-esteem (2) sex × time-varying parental depression (3) sex × time-stable parental depression (4) sex × self-esteem × time-varying parental depression, and (5) sex × self-esteem × time-stable parental depression. To produce the final reduced model, the multivariate Wald test was used to determine if the set of interactions significantly contribute to the model; significant interactions were retained in the model. Post hoc analyses were then used to probe the nature of significant interactions in the final model. All analyses were conducted using PROC MIXED in SAS version 9.3 [34].

Results

Sample characteristics

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of the study variables. Approximately half of the sample were males (51.48%). The mean age at baseline was 13.29 years. The most frequently reported parental education level was senior high school and about 18% of participants came from a single-parent household. The majority of the families (44.13%) had a monthly income between TWD 30,000 and TWD 59,999. Mothers generally reported higher levels of depression than fathers at each wave.

Characterizing the trajectory of adolescent depression

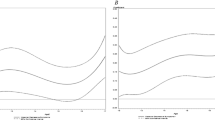

The trajectory of adolescent depression is depicted in Fig. 1 and the results of the unconditional model are presented in Supplementary Table 1. Our results indicated that the average developmental trajectory of adolescent depression was quadratic, increasing from ages 13 to 18 (positive liner slope, B = 0.046, p < 0.001) and then slightly decreasing from age 19 onward (negative quadratic slope, B = − 0.004, p < 0.001). The significant random intercept (B = 0.124, p < 0.001) and random slope (B = 0.001, p < 0.001) suggests that there was meaningful individual variability in both the initial level and the rate of change in adolescent depression over time.

Main effects of time-varying and time-stable parental depression

The main effects of maternal and paternal depression are presented in Model 1 of Tables 2 and 3, respectively. The time-stable effects of maternal and paternal depression were both significant for adolescent depression. Specifically, adolescents whose mother and father reported higher average levels of depression during the study period had higher levels of depression across the waves (B = 0.10 and 0.11 for maternal and paternal depression, respectively; both p < 0.001). Unexpectedly, the time-varying effects of maternal and paternal depression were both nonsignificant, indicating that the time-varying spike in parental depression was not associated with adolescent depression.

Moderated effects of self-esteem

Model 2 in Tables 2 and 3 shows the results for the moderated effects of self-esteem in the association between maternal depression and adolescent depression, and between paternal depression and adolescent depression, respectively. Self-esteem significantly moderated the time-stable effects of maternal depression (B = − 0.06, p < 0.05), but not paternal depression on adolescent depression. The nature of the significant interaction between self-esteem and time-stable maternal depression was further examined by conducting a post hoc analysis to understand the time-stable effects of maternal depression on adolescent depression at high and low levels of self-esteem (i.e., one standard deviation above and below the mean, respectively). As illustrated in Fig. 2, the effects of time-stable effects of maternal depression on adolescent depression were weaker in adolescents with high levels of self-esteem than those with low levels of self-esteem (B = 0.08 and 0.12, respectively).

Regarding the time-varying effects of parental depression, there was no evidence of moderated effects of self-esteem in either the association between the time-varying effects of maternal depression and adolescent depression or between the time-varying effects of paternal depression and adolescent depression.

Sex differences

We also tested whether there were sex differences in the main or interacted effects of parental depression and self-esteem on adolescent depression (results not shown). Multivariate Wald tests for the two- and three-way interactions with sex were not significant, indicating that the main effects of parental depression on adolescent depression and the moderated effects of self-esteem in the association between parental depression and adolescent depression did not vary by sex.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to disentangle the time-stable and time-varying effects of intergenerational transmission of depression. Specifically, we examined whether adolescent depression is more severe when parents show higher average levels of depression over time (time-stable effects) or when parents reported that their depression is more severe than normal (time-varying). We also investigated whether adolescent self-esteem buffered the risks of intergenerational transmission of depression. Consistent with expectations, we found significant time-stable effects of parental depression on adolescent depression. This intergenerational transmission of depression was further found to vary by adolescent self-esteem; however, the buffering effects of self-esteem were only significant for the influences of maternal depression. Unexpectedly, no significant time-varying effect of parental depression on adolescent depression was observed.

Consistent with previous findings on the intergenerational transmission of depression [7, 8], the current findings demonstrate significant associations between time-stable effects of maternal and paternal depression on adolescent depression from ages 13 to 23. Specifically, our results support the hypothesis that the adolescents of parents with higher average levels of depression over time had higher levels of depression during the same period of time than those of parents with lower average levels of depression. Both genetic and environmental factors have been found to contribute to the similarities in manifestations of depression across generations [37] and several explanations in addition to heritability have also been proposed to explain the intergenerational transmission of depression, including neuro-regulatory dysfunction, exposure to parental negative cognitions and behaviors, and increased stress in the family (Goodman and Gotlib [38]). For example, the intergenerational interpersonal stress model of depression indicates that the negative influences of parental depression on offspring depression are largely due to the stressful conditions in families, including family, marital, and parenting stress, as well as maladaptive parenting [39]. Similarly, a “launch and grow” model of intergenerational transmission of depression suggests that parental depression is an earlier risk factor, which disrupts certain processes during development, such as family relationships, and in turn sets the course for the growth of children’s depression over time [40].

Building on prior research, our results further suggest that the extent of intergenerational transmission of depression depends on levels of adolescent self-esteem. Despite studies that have sought to understand continuity in depression across generations and have generally acknowledged that adolescents vary in susceptibility to the risk of parental depression [19, 20], no previous study has ever tested whether individual self-esteem could help withstand the negative influences of parental depression. In accordance with the perspectives from the self-esteem model of depression [22], we found significant buffering effects of adolescent self-esteem in the intergenerational transmission of depression such that the effects of maternal depression were weaker for adolescents with higher than lower levels of self-esteem. Some mechanisms might be responsible for the buffering effects of self-esteem observed in the current study. Research has suggested that individuals with high self-esteem are more resilient [41, 42] and often encompass more coping resources [43] that help against the risks of stressful circumstances, such as parental depression, than those with lower levels of self-esteem. The differential coping strategies used by individuals with varying levels of self-esteem may also help explain the observed buffering effects. For example, individuals with low self-esteem were found to cope by directly confronting stressful events, whereas those with high self-esteem usually coped by lowering their appraisal of the importance of the event, which helped avoid maladaptive behaviors in such situations [23]. In addition, evidence has found links between self-esteem and human information processing [24], indicating that recovery from negative experiences may require less effort for individuals with higher self-esteem because they might perceive such negative events as less threatening.

The observed buffering effects of self-esteem, however, were only significant for the intergenerational transmission of maternal depression. Several explanations are proposed. First, compared to the model predicting adolescent depression from maternal depression, our sample size for the model examining the effects of paternal depression was much smaller, which may limit the statistical power to detect a significant moderating effect of self-esteem. Second, the variations in paternal depression in the current sample were likely not large enough to produce significant statistical interactions, which require variations in both the independent variable and the moderator [44]. In addition, the nonlinearity of the independent variable and the moderator is likely to pose difficulties in the detection of moderating effects [45]. It is also possible that the effects of paternal depression on adolescent depression are buffered only by an even higher level of self-esteem. Because there are currently no other studies exploring whether the intergenerational transmission of paternal depression varies by the levels of self-esteem, more research is needed to clarify these relationships.

Counter to our hypothesis, time-varying spikes in parental depression did not contribute to elevated levels of depression in adolescents. That is, adolescents did not report higher levels of depression at time points when their parents reported higher-than-average levels of depression. The reason for not observing a significant time-varying effect may be that the influences of intergenerational transmission of depression only become evident after the depressive symptoms of parents are present over a certain period of time. A small fluctuation in parental depression may not produce effects that are strong enough to influence levels of depression in adolescents. In addition, there may be other variables, such as social support, that were not controlled for in our model, but that could suppress the influences of time-varying spikes in parental depression on adolescent depression. Future research should continue exploring the extent to which adolescent depression is affected by the fluctuation of depression in their parents.

There is also no support for the hypothesis that the intergenerational transmission of depression varied by sex of the adolescent. Our study found that male and female adolescents were at equally higher risk for depression under the influences of maternal and paternal depression. The current findings support the views of the parent equivalent socialization hypothesis that suggests that mothers and fathers affect their sons and daughters in the same way [46]. There are also studies [7, 47] that found no differences in outcomes of daughters and sons with respect to the effects of parental depression, although some evidence did show sex-specific intergenerational transmission of depression [28,29,30,31]. Different sample characteristics, study designs, and analytical strategies may have contributed to these discrepancies. For example, compared to the past research that usually examined intergenerational transmission of depression among children and young adolescents [19, 48, 49], the age of the current sample was older. It is likely that sex differences in the effects of parental depression can only be observed during a particular developmental period, possibly in a younger age group because later in development, offspring are less exclusively dependent on their parents, with peers and other environmental factors having more influence, and potentially attenuating some of the sex-specific transmission of depression from parents [7]. In addition, unlike most existing research that was cross-sectional or used only two time points to test hypotheses, we disentangled the time-varying and time-stable effects of parental depression on adolescent depression from adolescence to young adulthood. Because sex-specific intergenerational transmission of depression remains uncertain, more longitudinal and methodologically rigorous studies are warranted to understand the underpinning transmission process.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several strengths. Our data came from a large community sample with assessments of both mothers and fathers, and repeated follow-ups of adolescents. The longitudinal nature of the data allowed us to examine developmental trajectories of depression from adolescence through young adulthood. Moreover, we were able to disentangle the time-stable and time-varying influences of parental depression on adolescent depression, thus providing information on both who is at risk for depression and when they are at risk. This is also the first study to examine the moderating role of self-esteem in the intergenerational transmission of depression. Finally, we applied multiple imputation techniques to minimize attrition effects, and the use of both parent and adolescent reports of depression further strengthened the robustness of our study findings.

Nevertheless, some limitations are worth noting. First, our sample was from northern Taiwan and was characterized by nonclinical levels of depression, limiting the ability to draw conclusions regarding the development of major depressive disorder in adolescents. The generalizability of the current findings was further constrained by the fact that far fewer fathers than mothers participated in the study. In addition, our measure of depression relied on self-reporting, which could lead to under- or over-estimation of symptom severity. The use of an objective assessment of depression could strengthen our study results. In this study, we investigated how self-esteem moderated the intergenerational transmission of depression. However, there could be additional factors that moderate the observed association, such as family structure, parenting styles, and parents’ expression and regulation of their own emotions. Furthermore, the measures of maternal and paternal depression in this study were not simultaneously assessed at each wave, reducing our ability to examine the joint effects of maternal and paternal depression on adolescent depression. Finally, limited by the use of secondary data, our study design could not infer causality between parental depression and adolescent depression. It is likely that the examined link is bidirectional and that other factors (e.g., shared genetic and environmental factors) may also influence the transmission process.

Conclusion and clinical implications

This study demonstrates the detrimental effects of both maternal and paternal depression on the development of depression in offspring from adolescence to young adulthood. Because treating parental depression can have a positive impact on an offspring’s health outcomes [50], interventions of adolescent depression could benefit from further targeting their depressed parents. In addition, because we observed that the risk of intergenerational transmission of depression to male and female adolescents are comparable and not dependent on the sex of parents, clinical professions may wish to pay equal attention to females and males under the influences of maternal and paternal depression. Finally, the significant buffering effects of self-esteem in the current study provide valuable information on protective factors that prevention and intervention could target to mitigate the risks of intergenerational transmission of depression. Specifically, by enhancing the adolescent’s self-esteem, the negative effects of maternal depression could be minimized. Clinicians could also stratify patients according to their levels of self-esteem and pay greater attention to those with low self-esteem because such patients are more vulnerable to the influences of maternal depression. Furthermore, tailored interventions could be developed for patients with different levels of self-esteem to improve depression.

References

Greden JF (2001) The burden of recurrent depression: causes, consequences, and future prospects. J Clin Psychiatr 62(22):5–9

Richards D (2011) Prevalence and clinical course of depression: a review. Clin Psychol Rev 31(7):1117–1125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.07.004

Polanczyk GV, Salum GA, Sugaya LS, Caye A, Rohde LA (2015) Annual research review: a meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatr 56(3):345–365. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12381

Goodman E, Whitaker RC (2002) A prospective study of the role of depression in the development and persistence of adolescent obesity. Pediatr 110(3):497–504

Measelle JR, Stice E, Hogansen JM (2006) Developmental trajectories of co-occurring depressive, eating, antisocial, and substance abuse problems in female adolescents. J Abnorm Psychol 115(3):524–538. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843x.115.3.524

Hankin BL, Young JF, Abela JR, Smolen A, Jenness JL, Gulley LD, Technow JR, Gottlieb AB, Cohen JR, Oppenheimer CW (2015) Depression from childhood into late adolescence: Influence of gender, development, genetic susceptibility, and peer stress. J Abnorm Psychol 124(4):803–816. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000089

Goodman SH, Rouse MH, Connell AM, Broth MR, Hall CM, Heyward D (2011) Maternal depression and child psychopathology: a meta-analytic review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 14(1):1–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-010-0080-1

Gelaye B, Rondon MB, Araya R, Williams MA (2016) Epidemiology of maternal depression, risk factors, and child outcomes in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Psychiatr 3(10):973–982. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(16)30284-x

Yan N, Zhou N, Ansari A (2016) Maternal depression and children’s cognitive and socio-emotional development at first grade: the moderating role of classroom emotional climate. J Child Fam Stud 25(4):1247–1256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0301-9

Monti JD, Rudolph KD (2017) Maternal depression and trajectories of adolescent depression: the role of stress responses in youth risk and resilience. Dev Psychopathol 29(4):1413–1429. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579417000359

Reinherz HZ, Giaconia RM, Hauf AM, Wasserman MS, Paradis AD (2000) General and specific childhood risk factors for depression and drug disorders by early adulthood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatr 39(2):223–231. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200002000-00023

Lee CM, Gotlib IH (1991) Adjustment of children of depressed mothers: a 10-month follow-up. J Abnorm Psychol 100(4):473–477

Delany-Brumsey A, Mays VM, Cochran SD (2014) Does neighborhood social capital buffer the effects of maternal depression on adolescent behavior problems? Am J Commun Psychol 53(3–4):275–285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-014-9640-8

Olino TM, McMakin DL, Nicely TA, Forbes EE, Dahl RE, Silk JS (2016) Maternal depression, parenting, and youth depressive symptoms: mediation and moderation in a short-term longitudinal study. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 45(3):279–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2014.971456

Brieant A, Holmes CJ, Deater-Deckard K, King-Casas B, Kim-Spoon J (2017) Household chaos as a context for intergenerational transmission of executive functioning. J Adolesc 58:40–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.05.001

Hussong AM, Huang W, Curran PJ, Chassin L, Zucker RA (2010) Parent alcoholism impacts the severity and timing of children's externalizing symptoms. J Abnorm Child Psychol 38(3):367–380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-009-9374-5

Flouri E, Ruddy A, Midouhas E (2017) Maternal depression and trajectories of child internalizing and externalizing problems: the roles of child decision making and working memory. Psychol Med 47(6):1138–1148. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291716003226

Brammer WA, Galan CA, Mesri B, Lee SS (2016) Parental ADHD and depression: time-varying prediction of offspring externalizing psychopathology. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2016.1183495

Schleider JL, Chorpita BF, Weisz JR (2014) Relation between parent psychiatric symptoms and youth problems: moderation through family structure and youth gender. J Abnorm Child Psychol 42(2):195–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-013-9780-6

Suveg C, Shaffer A, Morelen D, Thomassin K (2011) Links between maternal and child psychopathology symptoms: mediation through child emotion regulation and moderation through maternal behavior. Child Psychiatr Hum Dev 42(5):507–520. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-011-0223-8

Rosenberg M (1965) Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Brown GW, Harris T (1978) Social origins of depression. Free Press, New York

Kliewer W, Sandler IN (1992) Locus of control and self-esteem as moderators of stressor-symptom relations in children and adolescents. J Abnorm Child Psychol 20(4):393–413

Tobia V, Riva P, Caprin C (2017) Who are the children most vulnerable to social exclusion? The moderating role of self-esteem, popularity, and nonverbal intelligence on cognitive performance following social exclusion. J Abnorm Child Psychol 45(4):789–801. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-016-0191-3

Corning AF (2002) Self-esteem as a moderator between perceived discrimination and psychological distress among women. J Counsel Psychol 49(1):117–126. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-0167/49.1.117

Hankin BL (2006) Adolescent depression: description, causes, and interventions. Epilepsy Behav 8(1):102–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2005.10.012

Van Damme L, Colins OF, Vanderplasschen W (2014) Gender differences in psychiatric disorders and clusters of self-esteem among detained adolescents. Psychiatr Res 220(3):991–997. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.10.012

Mason WA, Chmelka MB, Trudeau L, Spoth RL (2017) Gender moderation of the intergenerational transmission and stability of depressive symptoms from early adolescence to early adulthood. J Youth Adolesc 46(1):248–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0480-8

Chen M, Johnston C, Sheeber L, Leve C (2009) Parent and adolescent depressive symptoms: the role of parental attributions. J Abnorm Child Psychol 37(1):119–130. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-008-9264-2

Cortes RC, Fleming CB, Catalano RF, Brown EC (2006) Gender differences in the association between maternal depressed mood and child depressive phenomena from grade 3 through grade 10. J Youth Adolesc 35(5):815–826. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-006-9083-0

Hops H (1992) Parental depression and child behaviour problems: implications for behavioural family intervention. Behav Change 9(3):126–138

Cyranowski JM, Frank E, Young E, Shear MK (2000) Adolescent onset of the gender difference in lifetime rates of major depression: a theoretical model. Arch Gen Psychiatr 57(1):21–27

Derogatis LR (1983) SCL–90–R: administration, scoring, and procedures manual II. Clinical Psychometric Research, Baltimore

SAS Institute Inc. (2011) SAS Software, Version 9.3. SAS Institute Inc., Cary

Saunders JA, Morrow-Howell N, Spitznagel E, Dore P, Proctor EK, Pescarino R (2006) Imputing missing data: a comparison of methods for social work researchers. Soc Work Res 30(1):19–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/30.1.19

Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS (2002) Hierarchical linear models: applications and data analysis methods, 2nd edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Sullivan PF, Neale MC, Kendler KS (2000) Genetic epidemiology of major depression: review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatr 157(10):1552–1562. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1552

Goodman SH, Gotlib IH (1999) Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: a developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychol Rev 106(3):458–490

Hammen C, Shih JH, Brennan PA (2004) Intergenerational transmission of depression: test of an interpersonal stress model in a community sample. J Consult Clin Psychol 72(3):511–522. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.72.3.511

Garber J, Cole DA (2010) Intergenerational transmission of depression: a launch and grow model of change across adolescence. Dev Psychopathol 22(4):819–830. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579410000489

Dumont M, Provost MA (1999) Resilience in adolescents: protective role of social support, coping strategies, self-esteem, and social activities on experience of stress and depression. J Youth Adolesc 28(3):343–363. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1021637011732

Balgiu BA (2017) Self-esteem, personality and resilience. Study of a students emerging adults group. J Edu Sci Psychol 7(1):93–99

Zeigler-Hill V (2011) The connections between self-esteem and psychopathology. J Contempor Psychother 41(3):157–164

Rutter M (1983) Statistical and personal interactions: facets and perspectives. In: Magnusson D, Allen V (eds) Human development: an interactional perspective. Academic Press, New York, p 295e319

McClelland GH, Judd CM (1993) Statistical difficulties of detecting interactions and moderator effects. Psychol Bull 114(2):376–390

O'Bryan M, Fishbein HD, Ritchey PN (2004) Intergenerational transmission of prejudice, sex role stereotyping, and intolerance. Adolesc 39(155):407–426

Currier D, Mann MJ, Oquendo MA, Galfalvy H, Mann JJ (2006) Sex differences in the familial transmission of mood disorders. J Affect Disord 95(1–3):51–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2006.04.014

Eberhart NK, Shih JH, Hammen CL, Brennan PA (2006) Understanding the sex difference in vulnerability to adolescent depression: an examination of child and parent characteristics. J Abnorm Child Psychol 34(4):495–508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-006-9020-4

Reeb BT, Conger KJ (2009) The unique effect of paternal depressive symptoms on adolescent functioning: associations with gender and father-adolescent relationship closeness. J Fam Psychol 23(5):758–761. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016354

Gunlicks ML, Weissman MM (2008) Change in child psychopathology with improvement in parental depression: a systematic review. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatr 47(4):379–389. https://doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181640805

Acknowledgements

Data analyzed in this study were collected by the research project “Taiwan Youth Project” sponsored by the Academia Sinica (AS-93-TP-C01). This research project was carried out by the Institute of Sociology, Academia Sinica, and directed by Dr. Chin-Chun Yi. The Center for Survey Research of Academia Sinica is responsible for the data distribution. The authors appreciate the assistance in providing data by the institutes and individuals aforementioned. The views expressed herein are the authors’ own.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology under Grant MOST 107-2410-H-002-084-MY2. The funding source had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the articles, or the decision to submit the articles for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chang, LY., Fu, M. Disentangling the effects of intergenerational transmission of depression from adolescence to adulthood: the protective role of self-esteem. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 29, 679–689 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-019-01390-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-019-01390-w