Abstract

Objectives

In the burning mouth syndrome (BMS), patients experience a burning sensation in the oral cavity with no associated injury or clinical manifestation. The etiology of this condition is still poorly understood, and therefore, treatment is challenging. The aim of this study is to perform a systematic review of treatment possibilities described in the literature for BMS.

Materials and methods

PubMed, Embase, and SciELO databases were searched for randomized clinical trials published between 1996 and 2016.

Results

Following application of inclusion and exclusion criteria, 29 papers were analyzed and divided into five subcategories according to the type of treatment described: antidepressants, alpha-lipoic acid, phytotherapeutic agents, analgesic and anti-inflammatory agents, and non-pharmacological therapies. In each category, the results found were compared with regard to the methodology employed, sample size, assessment method, presence or absence of adverse effects, and treatment outcomes.

Conclusions

The analysis revealed that the use of antidepressants and alpha-lipoic acid has been showing promising results; however, more studies are necessary before we can have a first-line treatment strategy for patients with BMS.

Clinical relevance

To review systematically the literature about Burning Mouth Syndrome treatment may aid the clinicians to choose the treatment modality to improve patients symptoms based on the best evidence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The burning mouth syndrome (BMS) is characterized by the presence of chronic orofacial pain despite the absence of any visible lesion in the patient’s oral mucosa [1]. The condition occurs more frequently in post-menopausal women and is relatively common, with an incidence estimated at 5:100,000 people; no predilection for a specific ethnicity or socioeconomic class has been identified [2]. The actual cause of BMS remains to be clarified, but several local, systemic, and psychological factors have been investigated as potentially related to the condition [1, 3, 4]. The term syndrome is used because BMS co-occurs with other subjective symptoms, such as xerostomia and dysgeusia [3].

BMS manifests as pain of unknown origin and a burning sensation affecting oral soft tissues, most commonly the tongue, but also lips, palate, gums, and buccal mucosa, and less frequently the floor of the mouth and oropharynx [3, 5]. For the diagnosis of BMS, the oral mucosa must be intact, with all clinical aspects within normality standards [3]. Differential diagnosis should rule out chronic orofacial pains and painful oral diseases that cause injuries to the mucosa, such as thrush, Sjögren’s syndrome, xerostomia and hyposalivation, among others, and also systemic conditions such as hormonal alterations, vitamin deficiencies, use of medications, and diabetes [6, 7] (Fig. 1).

Given the difficulties faced by practitioners in understanding the etiology of this syndrome, adequate treatment becomes challenging and several therapeutic options can be found in the literature. Therefore, the objective of this study was to conduct a systematic review of therapeutic possibilities for BMS, the question behind the review being “what is the best treatment for BMS?”

Materials and methods

Databases and search strategy

This study was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA checklist [8]. The PubMed, Embase, and SciELO databases were searched using the following keywords combined: “(burning mouth syndrome [MeSH Terms] OR burning mouth syndrome [Supplementary Concept] OR burning mouth syndrome [All Fields] OR stomatodynia [Supplementary Concept] OR stomatodynia [All Fields] AND (“therapy”[Subheading] OR “therapy”[All Fields] OR “treatment”[All Fields] OR “therapeutics”[MeSH Terms] OR “therapeutics”[All Fields])”. Randomized clinical trials reporting the effects of different treatments for BMS were selected. The search focused on papers published between 1996 and 2016, and was performed on November 27, 2016. This systematic review was registered at the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews with protocol no. CRD42017054237.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

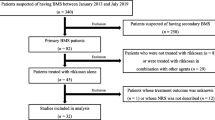

After searching the three databases using the selected keywords, a total of 233 papers were retrieved. Only randomized clinical trials were selected. After reviewing title and abstracts, 157 were found to be duplicates and 5 were excluded because they were published in languages other than English. The complete article review resulted in 19 papers excluded because they were not randomized clinical trials (case reports, letters to the editor, clinical observations with no control group, and literature reviews), and 23 were excluded because they focused on other conditions and not BMS. As a result, our final review comprised 29 papers (Fig. 2).

Analysis of results

Data from selected papers were entered into tables for subsequent analysis, divided into five subcategories according to the type of treatment assessed.

Analysis of biases

Following data analysis, papers were assessed with regard to possible biases. We evaluated patient randomization, whether both patients and research staff were blinded to group allocation, and the statistical tests employed. In case of doubts, an email would be sent to the corresponding author asking for more information.

Results

Following literature search and selection, a total of 29 papers were included in the analysis. These papers were divided into five subcategories, as described below.

Antidepressants

This category included papers in which BMS symptoms were treated with topical or oral antidepressants (Table 1). We found six papers: two using systemic clonazepam compared to placebo [9] and acupuncture [10], two using topical clonazepam comparing its effectiveness with placebo [11, 12], one using trazodone compared to placebo [13], and one using paroxetine compared to sertraline hydrochloride and amisulpride [14]. Treatment time for all substances ranged from 4 to 9 weeks. The most common adverse effects were drowsiness and dizziness, reported in four of six papers. With regard to treatment, clonazepam topical presented improvement in the two articles studied [11, 12]. Already in its systemic use, it only showed improvement in one of the papers [9]. Trazodone was not effective in improving BMS symptoms [13], whereas paroxetine, sertraline hydrochloride, and amisulpride equally improved symptoms at similar levels—the latter three, however, were not compared to placebo [14].

Alpha-lipoic acid (ALA)

Alpha-lipoic acid (ALA) is a compound produced at small amounts in the human body. It is essential to the functioning of different oxidative enzymes involved in metabolism. Currently, it is believed that ALA, or its reduced form, dihydrolipoic acid (DHLA), has several biochemical functions, acting as a biological antioxidant, chelating agent for metals, reducer of oxidized forms of other antioxidants, such as vitamins C and E and glutathione (GSH), and modulator of the signaling transduction of several pathways, e.g., insulin and nuclear factor kappa B [15, 16].

We found seven papers that assessed the effectiveness of ALA in the treatment of BMS (Table 2). In all seven papers, ALA was administered systemically at concentrations ranging from 400 to 800 mg, divided into two or three daily administrations, and most studies lasted for 2 months [4, 15,16,17,18,19,20]. With regard to side effects, only two studies reported patients with gastrointestinal discomfort [18, 19]. Five studies assessed patients after the end of the treatment protocol: four of them after 2 months [4, 18,19,20] and one after 1 year [15]. All studies were placebo-controlled, and three of them compared and/or associated the use of ALA with other substances. Of the seven studies, only one did not find a significant reduction in burning after treatment [19]. The other six reported improved symptoms, even though ALA was superior to placebo in only four [4, 15, 16, 19].

Phytotherapeutic agents

Another group of therapies used in the treatment of BMS are natural substances, including a wide variety of agents (Table 3). We found seven papers in this category [21,22,23,24,25,26,27], with drugs being administered either topically or systemically. Each of the seven studies analyzed a different substance. Minimal side effects were reported: one patient with drowsiness and weight gain [25]; and another with insomnia and two patients with burning after the use of capsaicin 0.02% oral rinse [26]. All seven substances caused symptom improvement.

In the two papers testing the effectiveness of Catuama [28], and capsaicin 0.02% oral rinse [26], significant improvement was observed when compared to placebo. The other five papers, testing the use of 2% chamomile gel [21], urea 10% [23], a spray containing lycopene-enriched virgin olive oil (300 ppm) [22], the use of a tongue protector associated with 0.5 mL of Aloe Vera 70% [24], and Hypericum perforatum extract 300 mg [27], reported effectiveness in symptom reduction, however, without statistical difference when compared with the placebo/control groups.

Analgesic and anti-inflammatory agents

Another category of medications investigated for the treatment of BMS included analgesic and anti-inflammatory drugs (Table 4). Four papers tested topical anesthesia with 5 mg bupivacaine lozenges [29], topical anesthesia with lidocaine [30], oral administration of Lafutidine 10 mg associated with gargling with azulene 4% [31], and Benzydamine hydrochloride 0.15% oral rinse [32].

Adverse effects were described in the papers testing bupivacaine (burning sensation in eight patients treated with bupivacaine and in five receiving placebo) [29] and Lafutidine (two patients reported minimal effects) [31]. No side effects were reported for lidocaine [30]. Of the effects reported, none resulted in treatment abandonment. In this subcategory, 5 mg bupivacaine lozenges and Lafutidine 10 mg were statistically superior to placebo in symptom improvement [29, 31]. Conversely, topical anesthesia with lidocaine and oral rinsing with Benzydamine hydrochloride 0.15% did not show significant results with regard to BMS symptom improvement [30, 32].

Non-pharmacological therapies

The remainder of the papers that tested treatments for BMS used strategies categorized as non-pharmacological, i.e., that did not fit any of the preceding subcategories. A total of seven papers were included in this group (Table 5), being two already present in other categories [10, 24]. In these papers, five different therapies were identified, namely laser techniques [25, 33], repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) [34], acupuncture [10], use of tongue protectors [24, 35], and psychotherapy [36]. Of these seven papers, only the one using rTMS reported side effects: 12 patients complained of headache at the beginning of the study. In the other studies, no side effects were reported.

With regard to treatment results, three papers observed statistically significant improvement with the strategy tested when compared to placebo, namely the ones using rTMS [34], laser techniques (infrared and red) [25], and tongue protector [35]. Acupuncture [10], use of tongue protector associated or not with Aloe Vera 70% [24], and use of infrared laser [33] showed symptom improvement, however, without statistically significant differences in relation to the control groups. No symptom improvement was found with psychotherapy [36].

Analysis of biases

In the study quality analysis, all studies mentioned randomization: Nine informed that patients were randomly allocated but did not inform how this was accomplished; the other 20 specified the method employed (computer software, web sites, or list of numbers). Also, most studies reported patient blinding, offering similar formulations (similar appearance and administration) to both the experimental group and that taking the placebo. However, we also found studies in which patient blinding was not a concern, especially when therapies involved personal interventions or combined treatments. Conversely, with regard to examiner blinding, most studies did not report or specify how this was achieved, and only 12 papers detailed the process (Table 6). Due to the great heterogeneity of the studies included, it was not possible to conduct a meta-analysis.

Discussion

BMS remains poorly understood with regard to both its etiology and treatment. It is described as the presence of chronic orofacial pain in the absence of any detectable injury in the patient’s oral mucosa [1]. Several factors have been suggested as possible causes of BMS, including local, systemic, and psychological characteristics [1, 3]; even risk factors have been researched to try to understand patients with BSM [37]. Because a well-defined etiology is lacking, a number of diverse treatments have been proposed in the literature to deal with this condition. However, such therapies do not always take into consideration the possible causes of burning in the oral cavity. Moreover, a totally effective protocol for the treatment of BMS is not currently available.

In the present review, we divided therapies into five categories. In the antidepressant category, we found reports on the use of both systemic clonazepam [9, 10] and topical clonazepam [11, 12]. Clonazepam is a benzodiazepine and an agonist for gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors; this receptor is widely distributed in the central nervous system and also along the peripheral tissues, and this medication, acting in this receptor, can present good results in the treatment of this syndrome [11]. Used systemically, clonazepam causes inhibition of the central nervous system as a result of its anticonvulsive action, leading to sedation, muscle relaxation, and tranquilization [38]. Used topically, clonazepam has been shown to reduce BMS symptoms without the adverse effects associated with systemic use [11, 12]. Therefore, topical use of clonazepam seems to be a promising alternative for the treatment of BMS. More studies, with larger samples and longer follow-up times, are required to confirm these preliminary findings.

Drugs such as amisulpride (50 mg/day), paroxetine (20 mg/day), and sertraline hydrochloride (50 mg/day) have also been reported to improve symptoms in BMS—paroxetine and sertraline hydrochloride are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [14]. This category not only presented positive results but also showed the highest number of adverse effects, including dizziness, insomnia, nausea, and drowsiness [10,11,12,13,14]. The occurrence of side effects should be taken into consideration when prescribing these drugs, especially because of their systemic administration, which may bring other problems to the patient.

As previously mentioned, ALA is produced in the human body at small amounts; its presence is essential to the functioning of different oxidative enzymes involved in metabolism [15, 16]. ALA works as a coenzyme, producing energy (adenosine triphosphate (ATP)) and improving glucose metabolism. Moreover, ALA seems to stimulate the production of nerve growth factor (NGF) and has been used in the treatment of diabetic neuropathy [39]. Another mechanism of action of ALA reported in the literature is the increase in cellular levels of glutathione, which when low can cause oxidative stress, inflammation, and damage to the nerves, leading to peripheral neuropathy; thus, ALA is beneficial in this supplementation [40, 41]. ALA was tested in seven of the papers included in the present review, and all of them, except one [19], found positive results. Cavalcanti and da Silveira, and Carbone et al. compared ALA with placebo and found improvement, however, without differences between the groups, suggesting that psychological aspects of patients with BMS should be taken into consideration. The other papers tested ALA vs. placebo but included other experimental groups, using, e.g., GABA [17] and capsaicin [42], all with positive results. In the study by [18], treatment was maintained for 1 month only (compared to 2 months in all other papers). However, differences in treatment duration do not seem to have an influence on treatment outcomes, as the only study that did not find positive effects of ALA in the treatment of BMS [19] used the standard 2-month protocol [42]. Considering that ALA presented results superior to placebo in only four of the seven studies, its efficacy is still controversial. More studies, with longer follow-up, could shed more light on its efficacy.

The use of phytotherapeutic agents for medical purposes is a millennium-old practice. Phytotherapy or herbal medicine, derived from popular knowledge, has been increasingly investigated to confirm the beneficial effects of the substances employed. In our literature review, seven papers were found in this segment, testing different protocols; all seven reported positive results, with symptom improvement. Again, it should be taken into consideration that five papers described symptom improvement [21,22,23,24, 27], but one of them also observed improvement in the placebo group. Once again, these results reinforce the importance of looking into psychological characteristics of patients with BMS. Treatments with the herbal drug Catuama 310 mg [28] and capsaicin 0.02% oral rinse [26] yielded positive results in improving BMS symptoms when compared to placebo, suggesting that these potential therapies should be studied in more detail. One last aspect that favors the potential use of phytotherapy in BMS is the virtual absence of side effects.

In our review, laser therapy emerged as a non-pharmacological treatment option. Low-intensity laser radiation is used due to its capacity to modulate metabolic, biochemical, and photophysical processes that transform laser light into energy that is useful to cells. The energy provokes mitochondrial reactions and increases in ATP production, intracellular calcium levels, and number of mitoses. The analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and tissue repair properties of low-intensity laser radiation are consensual. In BMS, laser therapy seems to have a positive effect only if used more frequently, i.e., three times weekly for 3 weeks [25, 33]—studies with shorter treatment durations failed to find results superior to placebo. The analgesic action of laser therapy is related to the inhibition of pain mediators and the increase of the cell membrane potential, reducing the speed of conduction of the nerve impulse [43, 44], and this may be the explanation for the results found for this treatment.

Several treatment modalities were found in the literature for BMS, but very few were tested in more than one randomized clinical trial with a control group; this scarcity of clinical trials prevents the comparison of results. Therapies involving psychotherapy [36], topical anesthesia with lidocaine [30], and benzydamine hydrochloride 0.15% oral rinse [32] failed to obtain significant results. This scenario underscores the need to investigate the effectiveness of a multidisciplinary treatment approach to patients with BMS. Some of the therapies described in the papers showed positive results, e.g., the use of 5 mg bupivacaine lozenges three times daily for 2 weeks [29] and rTMS daily for 14 days [34]. Both therapies were associated with statistically significant symptom reductions compared to placebo; however, some patients reported side effects such as burning sensation after the use of lozenges and headache after rTMS sessions. Therefore, even though these therapies were associated with symptom improvement, the occurrence of side effects urges them to be better evaluated before being indicated.

An important point to be considered is the improvement of the symptoms reported by the patients under placebo treatment. In our review, seven articles fit into this situation [11, 13, 18, 19, 25, 31, 33], where placebo treatment showed improvement of symptoms even though it was not statistically significant, thus showing that psychological factors may be related to BMS pathogenesis. The articles reported the exclusion of patients with other alterations (systemic or psychological), which leads us to suggest that to be under a clinical follow-up already is beneficial for BMS patients. However, we can not only focus on psychological treatment, since in the study where the efficacy of psychotherapy was evaluated solely [36], no promising results were found either. Therefore, we can suggest that combined therapies be used, taking into account the symptoms and psychological aspects of the patients.

In summary, assessment of the papers included in the present review revealed that, in addition to the difficulties involved in diagnosing BMS, major difficulties are also present in treatment decision-making. Initially, more research is warranted to improve our understanding of the etiology of this syndrome, up to possible genetic polymorphisms have been studied to try to understand the mechanisms of the BMS, without success [45]. In the papers here reviewed, patients with disorders other than true BMS were excluded. Another important point is the assessment of treatment duration and follow-up time: The syndrome has continuous, long-lasting symptoms, and treatment should be long enough and last for at least 2 months, as most papers propose. Finally, more studies, with larger samples, are necessary to further assess existing therapies, testing each of the protocols in randomized clinical trials with control groups and adequate blinding.

Final remarks

Several treatment modalities are available for BMS, but none is totally satisfactory from the point of view of evidence-based research, given the heterogeneity of the studies and therapies employed. The use of Clonazepan and ALA was the only tested in more than two studies and showed promising results, but more studies, with larger samples, are necessary before we can have a first-line treatment strategy for patients with BMS. Also, it is important to point out that in some studies, both the therapies assessed and placebo showed similar results. This underscores the need to look into psychological and/or psychiatric characteristics of the patients, possibly requiring a multidisciplinary approach to the treatment of BMS.

Change history

30 July 2019

The original version of this article contained two mistakes. First, in the subchapter ���Alpha-lipoic acid (ALA)��� page 1895, reference 4 is cited three times, however reference 42 is the correct one.

30 July 2019

The original version of this article contained two mistakes. First, in the subchapter ���Alpha-lipoic acid (ALA)��� page 1895, reference 4 is cited three times, however reference 42 is the correct one.

References

Jimson S, Rajesh E, Krupaa RJ, Kasthuri M (2015) Burning mouth syndrome. J Pharm Bioallied Sci 7:S194–S196. https://doi.org/10.4103/0975-7406.155899

Oliveira GMR, Pereira HSC, Silva-Júnior GO et al (2013) Síndrome da Ardência Bucal: aspectos clínicos e tratamento. Revista do Hospital Universitário Pedro Ernesto, UERJ 12:21–29

Scala A, Checchi L, Montevecchi M, Marini I, Giamberardino MA (2003) Update on burning mouth syndrome: overview and patient management. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med Off Publ Am Assoc Oral Biol 14:275–291

Marino R, Picci RL, Ferro G, Carezana C, Gandolfo S, Pentenero M (2015) Peculiar alexithymic traits in burning mouth syndrome: case–control study. Clin Oral Investig 19:1799–1805. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-015-1416-5

Barker K, Savage N (2005) Burning mouth syndrome: an update on recent findings. Aust Dent J 50:220–223. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1834-7819.2005.tb00363.x

López-Jornet P, Camacho-Alonso F, Andujar-Mateos P et al (2010) Burning mouth syndrome: an update. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 15:e562–e568. https://doi.org/10.4317/medoral.15.e562

Aravindhan R, Vidyalakshmi S, Kumar MS, Satheesh C, Balasubramanium AM, Prasad VS (2014) Burning mouth syndrome: a review on its diagnostic and therapeutic approach. J Pharm Bioallied Sci 6:S21–S25. https://doi.org/10.4103/0975-7406.137255

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol 62:1006–1012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005

Heckmann SM, Kirchner E, Grushka M, Wichmann MG, Hummel T (2012) A double-blind study on clonazepam in patients with burning mouth syndrome. Laryngoscope 122:813–816. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.22490

Jurisic Kvesic A, Zavoreo I, Basic Kes V, Vucicevic Boras V, Ciliga D, Gabric D, Vrdoljak DV (2015) The effectiveness of acupuncture versus clonazepam in patients with burning mouth syndrome. Acupunct Med 33:289–292. https://doi.org/10.1136/acupmed-2015-010759

Gremeau-Richard C, Woda A, Navez ML, Attal N, Bouhassira D, Gagnieu MC, Laluque JF, Picard P, Pionchon P, Tubert S (2004) Topical clonazepam in stomatodynia: a randomised placebo-controlled study. Pain 108:51–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2003.12.002

Rodríguez de Rivera Campillo E, López-López J, Chimenos-Küstner E (2010) Response to topical clonazepam in patients with burning mouth syndrome: a clinical study. Bull Group Int Rech Sci Stomatol Odontol 49:19–29

Tammiala-Salonen T, Forssell H (1999) Trazodone in burning mouth pain: a placebo-controlled, double-blind study. J Orofac Pain 13:83–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3913(99)70067-3

Maina G, Vitalucci A, Gandolfo S, Bogetto F (2002) Comparative efficacy of SSRIs and amisulpride in burning mouth syndrome: a single-blind study. J Clin Psychiatry 63:38–43. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.v63n0108

Femiano F, Scully C (2002) Burning mouth syndrome (BMS): double blind controlled study of alpha-lipoic acid (thioctic acid) therapy. J Oral Pathol Med Off Publ Int Assoc Oral Pathol Am Acad Oral Pathol 31:267–269. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0714.2002.310503.x

Palacios-Sánchez B, Moreno-López L-A, Cerero-Lapiedra R et al (2015) Alpha lipoic acid efficacy in burning mouth syndrome. A controlled clinical trial. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 20:e435–e440. https://doi.org/10.4317/medoral.20410

López-D’alessandro E, Escovich L (2011) Combination of alpha lipoic acid and gabapentin, its efficacy in the treatment of burning mouth syndrome: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 16:e635–e640. https://doi.org/10.4317/medoral.16942

Cavalcanti DR, da Silveira FRX (2009) Alpha lipoic acid in burning mouth syndrome—a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. J Oral Pathol Med Off Publ Int Assoc Oral Pathol Am Acad Oral Pathol 38:254–261. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0714.2008.00735.x

López-Jornet P, Camacho-Alonso F, Leon-Espinosa S (2009) Efficacy of alpha lipoic acid in burning mouth syndrome: a randomized, placebo-treatment study. J Oral Rehabil 36:52–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2842.2008.01914.x

Carbone M, Pentenero M, Carrozzo M, Ippolito A, Gandolfo S (2009) Lack of efficacy of alpha-lipoic acid in burning mouth syndrome: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Eur J Pain Lond Engl 13:492–496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.06.004

Valenzuela S, Pons-Fuster A, López-Jornet P (2016) Effect of a 2% topical chamomile application for treating burning mouth syndrome: a controlled clinical trial. J Oral Pathol Med Off Publ Int Assoc Oral Pathol Am Acad Oral Pathol 45:528–533. https://doi.org/10.1111/jop.12412

Cano-Carrillo P, Pons-Fuster A, López-Jornet P (2014) Efficacy of lycopene-enriched virgin olive oil for treating burning mouth syndrome: a double-blind randomised. J Oral Rehabil 41:296–305. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.12147

da SLA, de SJTT, Teixeira MJ, de SSRDT (2014) The role of xerostomia in burning mouth syndrome: a case-control study. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 72:91–98. https://doi.org/10.1590/0004-282X20130218

López-Jornet P, Camacho-Alonso F, Molino-Pagan D (2013) Prospective, randomized, double-blind, clinical evaluation of Aloe vera Barbadensis, applied in combination with a tongue protector to treat burning mouth syndrome. J Oral Pathol Med Off Publ Int Assoc Oral Pathol Am Acad Oral Pathol 42:295–301. https://doi.org/10.1111/jop.12002

Spanemberg JC, López López J, de Figueiredo MAZ et al (2015) Efficacy of low-level laser therapy for the treatment of burning mouth syndrome: a randomized, controlled trial. J Biomed Opt 20:098001. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.JBO.20.9.098001

Silvestre F-J, Silvestre-Rangil J, Tamarit-Santafé C, Bautista D (2012) Application of a capsaicin rinse in the treatment of burning mouth syndrome. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 17:e1–e4. https://doi.org/10.4317/medoral.17219

Sardella A, Lodi G, Demarosi F, Tarozzi M, Canegallo L, Carrassi A (2008) Hypericum perforatum extract in burning mouth syndrome: a randomized placebo-controlled study. J Oral Pathol Med Off Publ Int Assoc Oral Pathol Am Acad Oral Pathol 37:395–401. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0714.2008.00663.x

Spanemberg JC, Cherubini K, de Figueiredo MAZ, Gomes APN, Campos MM, Salum FG (2012) Effect of an herbal compound for treatment of burning mouth syndrome: randomized, controlled, double-blind clinical trial. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 113:373–377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oooo.2011.09.005

Treldal C, Jacobsen CB, Mogensen S, Rasmussen M, Jacobsen J, Petersen J, Lynge Pedersen AM, Andersen O (2016) Effect of a local anesthetic lozenge in relief of symptoms in burning mouth syndrome. Oral Dis 22:123–131. https://doi.org/10.1111/odi.12386

Grémeau-Richard C, Dubray C, Aublet-Cuvelier B, Ughetto S, Woda A (2010) Effect of lingual nerve block on burning mouth syndrome (stomatodynia): a randomized crossover trial. Pain 149:27–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2009.11.016

Toida M, Kato K, Makita H, Long NK, Takeda T, Hatakeyama D, Yamashita T, Shibata T (2009) Palliative effect of lafutidine on oral burning sensation. J Oral Pathol Med Off Publ Int Assoc Oral Pathol Am Acad Oral Pathol 38:262–268. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0714.2008.00736.x

Sardella A, Uglietti D, Demarosi F, Lodi G, Bez C, Carrassi A (1999) Benzydamine hydrochloride oral rinses in management of burning mouth syndrome. A clinical trial. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 88:683–686. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1079-2104(99)70010-7

Sugaya NN, da Silva ÉFP, Kato IT et al (2016) Low intensity laser therapy in patients with burning mouth syndrome: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Braz Oral Res 30:e108. https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-3107BOR-2016.vol30.0108

Umezaki Y, Badran BW, DeVries WH et al (2016) The efficacy of daily prefrontal repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) for burning mouth syndrome (BMS): a randomized controlled single-blind study. Brain Stimul 9:234–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brs.2015.10.005

López-Jornet P, Camacho-Alonso F, Andujar-Mateos P (2011) A prospective, randomized study on the efficacy of tongue protector in patients with burning mouth syndrome. Oral Dis 17:277–282. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1601-0825.2010.01737.x

Miziara ID, Filho BCA, Oliveira R, Rodrigues dos Santos RM (2009) Group psychotherapy: an additional approach to burning mouth syndrome. J Psychosom Res 67:443–448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.01.013

Netto FOG, Diniz IMA, Grossmann SMC, de Abreu MHNG, do Carmo MAV, Aguiar MCF (2011) Risk factors in burning mouth syndrome: a case–control study based on patient records. Clin Oral Investig 15:571–575. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-010-0419-5

Sun A, Wu K-M, Wang Y-P, Lin HP, Chen HM, Chiang CP (2013) Burning mouth syndrome: a review and update. J Oral Pathol Med 42:649–655. https://doi.org/10.1111/jop.12101

Singh U, Jialal I (2008) Alpha-lipoic acid supplementation and diabetes. Nutr Rev 66:646–657. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00118.x

Tirosh O, Sen CK, Roy S, Kobayashi MS, Packer L (1999) Neuroprotective effects of alpha-lipoic acid and its positively charged amide analogue. Free Radic Biol Med 26:1418–1426. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0891-5849(99)00014-3

Arivazhagan P, Panneerselvam C (2000) Effect of DL-alpha-lipoic acid on neural antioxidants in aged rats. Pharmacol Res 42:219–222. https://doi.org/10.1006/phrs.2000.0679

Marino R, Torretta S, Capaccio P, Pignataro L, Spadari F (2010) Different therapeutic strategies for burning mouth syndrome: preliminary data. J Oral Pathol Med Off Publ Int Assoc Oral Pathol Am Acad Oral Pathol 39:611–616. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0714.2010.00922.x

Pozza DH, Fregapani PW, Weber JBB et al (2008) Analgesic action of laser therapy (LLLT) in an animal model. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 13:E648–E652

Romeo U, Del Vecchio A, Capocci M et al (2010) The low level laser therapy in the management of neurological burning mouth syndrome. A pilot study. Ann Stomatol (Roma) 1:14–18

Kim M-J, Kim J, Chang J-Y, Kim YY, Kho HS (2017) Polymorphisms of interleukin-1β and MUC7 genes in burning mouth syndrome. Clin Oral Investig 21:949–955. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-016-1866-4

Funding

The work was supported by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (Brazil).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

de Souza, I.F., Mármora, B.C., Rados, P.V. et al. Treatment modalities for burning mouth syndrome: a systematic review. Clin Oral Invest 22, 1893–1905 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-018-2454-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-018-2454-6