Abstract

Survivors of childhood maltreatment (CM) may experience difficulties in the peripartum period and in adjustment to motherhood. In this study we examined a model wherein CM is associated with maternal self-efficacy and maternal bonding three months postpartum, through mediation of peripartum dissociation and reduced sense of control during childbirth and postpartum-posttraumatic-stress disorder (P-PTSD). Women were recruited in a maternity ward within 48 h of childbirth (T1, N = 440), and contacted three-months postpartum (T2, N = 295). Participants completed self-report questionnaires: peripartum dissociation, sense of control (T1), and CM, P-PTSD, postpartum-depression, maternal self-efficacy and bonding (T2). Obstetrical data were collected from medical files. Structural equation modeling was conducted to test the hypothesized model, controlling for mode of delivery and postpartum-depression. Reported CM included child emotional neglect (CEN; 23.5%), child emotional abuse (CEA; 16.3%), child sexual abuse (CSA; 12.9%) and child physical abuse (CPA; 7.1%). CM was positively associated with peripartum dissociation and P-PTSD (p < .001). Peripartum dissociation was positively associated with P-PTSD (p < .001). P-PTSD was negatively associated with maternal self-efficacy (p < .001) and maternal bonding (p < .001). Association between CM and maternal self-efficacy and bonding was serially mediated by peripartum dissociation and P-PTSD, but not by sense of control. Findings remained significant after controlling for mode of delivery and postpartum-depression. CM is a risk factor for adjustment to motherhood, owing to its effects on peripartum dissociation and P-PTSD. Implementation of a trauma-informed approach in obstetric care and recognition of peripartum dissociative reactions are warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Childbirth may sometimes be a traumatic experience; up to 10% of women suffer from postpartum post-traumatic stress symptoms and up to 4% develop postpartum post-traumatic stress disorder (P-PTSD) (Ayers 2004; Grekin and O’Hara 2014). Childbirth may be especially traumatic for survivors of childhood maltreatment (CM) (Do et al. 2022). Among women, the reported prevalence of CM is 18.4% for child emotional neglect (CEN), 16.3% for child physical neglect (CPN), 36.3% for child emotional abuse (CEA), 18.0% for child sexual abuse (CSA), and 22.6% for child physical abuse (CPA) (Stoltenborgh et al. 2015). Although CM is common among women, it is a concealed phenomenon owing to inadequate screening by healthcare professionals and lack of disclosure by survivors (Berry and Rutledge 2016; Friedman et al. 1992).

Previous studies identified CM (Lev-Wiesel et al. 2009b; Oh et al. 2016; Sexton et al. 2015) and diagnoses of pre-partum PTSD (Dekel et al. 2017; Ertan et al. 2021; Lev-Wiesel et al. 2009a; O’Donovan et al. 2014) as risk factors for P-PTSD. However, little is known about the mechanisms that underlie the development of P-PTSD in women with a history of CM.

A negative subjective birth experience has emerged as the most important predictor of P-PTSD in a systematic review of 36 articles that examined predictors of P-PTSD (Dekel et al. 2017). Feeling out of control is a salient characteristic of traumatic birth (Elmir et al. 2010) and low levels of sense of control during childbirth was identified as a risk factor for P-PTSD (Adewuya et al. 2006; Elmir et al. 2010; Soet et al. 2003). History of CM is associated with reduced intrapersonal empowerment (Banyard and LaPlant 2002) and sense of control (Arens et al. 2014). More specifically, analyses of childbirth experiences of adult survivors of CM suggest that lack of privacy and feelings of passive participation in the birth process may bear resemblance to CM experiences (Chamberlain et al. 2019) and reduce the sense of control (Montgomery 2013). During childbirth, CM survivors may experience intrusive memories of previous traumatic experiences (Leeners et al. 2016), triggered by perinatal pain, constraint and a lack of control or care settings that may be experienced as invasive and violating (Chamberlain et al. 2019). However, the role of sense of control as an explanation for the association between CM and P-PTSD has not previously been examined.

Another negative birth experience that is prevalent among CM survivors is peripartum dissociation (Lev-Wiesel and Daphna-Tekoah 2010), that may be evoked by intrusive memories. The relation between CM and dissociative symptoms is well established (Sar 2011), and given that peri-traumatic dissociation was found to be the strongest predictor of non-postpartum-related PTSD (Ozer et al. 2003), it is reasonable to assume that peripartum dissociation may constitute a risk factor for P-PTSD. However, the literature regarding peripartum dissociation and its relation to P-PTSD has been inconsistent. While one meta-analysis identified dissociation as an intrapartum risk factor related to P-PTSD (Ayers et al. 2016), a systematic review by Dekel et al. (2017) did not identify such a relationship.

CM history (Christie et al. 2018) and P-PTSD may also influence adjustment to motherhood, as PTSD symptoms may be associated with reduced maternal self-efficacy, impaired mother–child dyad interactions and impairments in mother–infant bonding (Garthus-Niegel et al. 2017; Martini et al. 2022; Muzik et al. 2013; Sexton et al. 2015). Dissociation might also impair adjustment to motherhood (Greene et al. 2020) and has been identified as a potential mediator between CM history and impaired maternal bonding (Williams et al. 2022). Reduced sense of control during childbirth was shown to challenge early adaptation to motherhood in a narrative analysis of traumatic birth stories (Cronin-Fisher and Timmerman 2023). However, this combination of factors has not yet been addressed systematically. Better understanding of how CM affects the peripartum period and adaptation to motherhood in women survivors of CM is of great relevance.

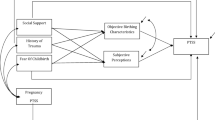

The aim of this study was to examine the mechanism underlying the association between CM and maternal self-efficacy and bonding, three months postpartum. We suggest a two-path model, according to which the associations between CM and maternal self-efficacy and bonding are mediated by peripartum dissociation and decreased sense of control during childbirth, leading to P-PTSD, which in turn mediates the associations between these variables and adaptation to motherhood. Finally, since cesarean section (CS) was shown to be a stronger predictor of P-PTSD than spontaneous vaginal delivery (SVD) (Carter et al. 2022), and due to the high comorbidity between P-PTSD and postpartum depression (Czarnocka and Slade 2000; Muzik et al. 2017), we controlled for both mode of delivery and postpartum depression.

Materials and methods

Participants and procedure

This longitudinal study was conducted from April 2018 through August 2020 among a convenience sample of adult postpartum women. Recruitment was in the maternity ward of a public hospital in Israel serving an economically and socially diverse community. On recruitment days, the researchers approached women in the maternity ward, within 48 h postpartum (T1). Exclusion criteria included: lack of knowledge of the local language and physical, emotional or psychiatric conditions hindering response to self-report questionnaires, including critical medical conditions, negative maternal or neonatal outcomes. Overall, we approached 636 women, of whom 440 agreed to participate (response rate- 69%). Following Institutional Review Board approval and provision of written informed consent, participants completed self-report questionnaires. Obstetrical data were collected from medical files. The researchers’ contact information was provided to all participants.

Three months postpartum (T2), participants received links for an online survey, through contact information they provided at T1. Two-hundred and ninety-five women (67.05% of those who participated at T1; 46.83% of the 636 that were approached in the maternity ward) completed the self-report questionnaires at T2. This sample size is in line with the recommended minimum of N = 250 for structural equation modeling (SEM; (Hu and Bentler 1999)).

Responders at T2 did not differ from dropouts in most background variables. Responders at T2 reported a somewhat higher level of education than dropouts (M = 14.71 ± 2.34 vs M = 14.11 ± 2.37, p = 0.01), and more dropouts reported that their income is considerably lower than the average wage as compared to T2 participants (n = 26, 20.2% vs n = 34, 11.7%, p = 0.04). T2 participants and dropouts did not differ in T1 assessments, i.e., sense of control and peripartum dissociation.

Participants who expressed emotional distress either at T1 or T2 were referred to the social worker on the maternity ward or to community support services, respectively.

Measures

Demographic and medical background

Demographic data, medical background and obstetrical information were retrieved from clinical files at T1.

Peripartum dissociation was assessed at T1, using an 8-item validated Hebrew version of the Peritraumatic Dissociative Experiences Questionnaire (PEDQ) (Shalev et al. 1996). Participants were asked to rate their experiences during labor, on a 5-point scale from (1) ‘not at all’ to (5) ‘completely’. One item, about pain perception, was omitted from analysis, due to the possible effect of analgesia. Mean scores were used, with higher scores representing greater levels of perinatal dissociation. Cronbach's alpha for the current sample was 0.82.

Sense of control during birth was assessed at T1, by the 10-item version of the Labor Agentry Scale (LAS) (Hodnett and Simmons-Tropea 1987). Participants were asked to rate their experiences on a 7- point scale from (1) ‘almost all of the time’ to (7) ‘never, or almost never’. Mean scores were used, with higher scores representing greater levels of sense of control. Cronbach's alpha for the current sample was 0.76.

Child maltreatment

CM was measured using the validated Hebrew version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) (Bernstein et al. 2003; Brenner and Ben-Amitay 2015). Due to the sensitivity of the immediate postpartum period, we decided to evaluate history of CM at T2 and not at T1. This scale consists of 28 items reflecting CEN, CPN, CEA, CSA, and CPA. The items were rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale with response options ranging from (1) ‘never true’ to (5) ‘very often true’. Sum scores were used, with higher scores representing greater levels of CM. Cutoff scores can be used, to classify subscale scores into severity quintiles: “none/minimal” (CEA < = 8, PA < = 7, CSA = 5, CEN < = 9, CPN < = 7), “low to moderate” (CEA > 8 and < = 12, CPA > 7 and < = 9, CSA > 5 and < = 7, CEN > 9 & < = 14, CPN > 7 and < = 9), “moderate to severe” (CEA > 12 and < = 15, CPA > 9 and < = 12, CSA > 7 and < = 12, CEN > 15 and < = 17, CPN > 9 and < = 12), and “severe to extreme” (CEA > = 16, CPA > = 13, CSA > = 13, CEN > = 18, CPN > = 13 (MacDonald et al. 2016). Cronbach’s alphas for the current sample were 88 for CEN, 0.45 for CPN, 0.79 for CEA, 0.89 for CSA, and 0.73 for CPA. Due to the low level of reliability of the score of CPN (see Paivio and Cramer 2004) we did not include it in the analyses.

P-PTSD symptoms

PTSD was assessed using the validated Hebrew version of the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) (Blevins et al. 2015; Horesh et al. 2018) was measured at T2. It contains 20 items assessing postpartum-induced posttraumatic symptoms. The items are rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1) ‘not at all’ to (5) ‘extremely’. Mean scores were used, with higher scores representing greater levels of P-PTSD. Cronbach's alpha for the current sample was 0.91. A cutoff score of 31 in the PCL-5 was used as a cutoff for probable PTSD (Bovin et al. 2016).

Maternal adjustment to motherhood 3 months postpartum was measured with 2 scales:

Maternal self-efficacy the 18-item Maternal Self-Efficacy Scale (MSES) (Kestler-Peleg et al. 2015) was measured at T2. Participants were asked to indicate the degree to which they agreed with the statements on a four-point scale ranging from (1) ‘not at all’ to (4) ‘very much’. Mean scores were used, with higher scores representing greater levels of perceived competence. Cronbach's alpha for the current sample was 0.85.

Maternal bonding was assessed at T2, using an 8-item Mother-to-Infant Bonding Scale (MIBS) (Taylor et al. 2005). Participants were asked to rate the extent each item describes their feelings, on a 4-point scale ranging from (1) ‘not at all’ to (4) ‘very much’. Mean scores were used, with higher scores representing greater levels of maternal bonding. Cronbach's alpha for the current sample was 0.81.

Depression was assessed at T2 using the validated Hebrew version of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) (Cox et al. 1987; Glasser et al. 1998), which evaluates overall emotional state since labor, with four response options each rated 0–3. Sum scores were used, with higher scores representing greater levels of depression. Cronbach’s alpha for the current sample was 0.89.

Data analysis

Missing data analysis using SPSS software (version 28) indicated that, across variables measured by the self-report questionnaires, 1.0–10.5% of values were missing. Little’s Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) model (Little 1988) indicated that the data were missing completely at random, χ2(473) = 511.32, p = 0.11. Missing data were replaced with maximum likelihood estimations based on all variables in the model, a procedure referred to as expectation maximization.

The associations between the study variables were examined by Pearson correlations and univariate analyses of variance (ANOVAs). The hypothesized model was tested using SEM, employing the AMOS software package (version 28). This technique enables users to examine the direct and indirect effects of the latent and observed constructs simultaneously, and to evaluate how well the hypothesized model’s structure fits the data. A latent variable of CM was indicated by four observed measured scores: CPA, CSA, CEA, and CEN. All other variables were indicated by their measured scores. Mode of delivery (vaginal/CS) and postpartum-depression were controlled. Two hundred bootstrap samples were used to test the significance of the serial mediation effects, in which peripartum dissociation, sense of control during childbirth, and P-PTSD were considered as mediators in the relation between CM and the outcome measures (maternal self-efficacy and maternal bonding).

The following fit indices were used to examine the fit of the hypothesized model to the data: Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Normed Fit Index (NFI), Tucker Lewis Index (TLI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and test of close fit (PCLOSE). For CFI, NFI, and TLI, values greater than 0.90 indicate an acceptable fit between the model and the data. For the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), values of less than 0.08 and a nonsignificant test of close fit (PCLOSE) represent a good fit (O’Boyle and Williams 2011), as well as a ratio of chi-square to degrees of freedom lower than 3 (Kline 1998).

Results

The participants’ demographic data and obstetric outcomes are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Prevalence of CM is presented in Table 3. Twenty-three percent reported some degree of CEN, 16.3% some degree of CEA, 12.9% some degree of CSA, and 7.1% some degree of CPA.

Thirteen women (4.1%) had scores of probable P-PTSD in the T2 assessments.

Table 4 presents the correlations between the study variables. All types of CM were associated with each other. Peripartum dissociation was positively associated with CEA, CEN, and negatively with sense of control during childbirth. P-PTSD symptoms, maternal bonding and maternal self-efficacy were associated with all study variables.

Research model

SEM indicated a good fit between the model and the data, χ2/df = 2.20, p < 0.001, NFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.94, CFI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.06, PCLOSE = 0.12. All of the four observed indicators for CM (CPA, CSA, CEA, and CEN) loaded significantly onto the corresponding hypothesized latent factor (p’s < 0.001). The results of the SEM are depicted in Fig. 1, with a presentation of the standardized estimates of the direct effects. The model explained 20% of P-PTSD, 44% of the variance of maternal self-efficacy, and 24% of maternal bonding, all evaluated at T2.

The model yielded the following direct effects: CM was positively associated with peripartum dissociation. CM was also positively associated with P-PTSD. Thus, the higher the levels of CM, the higher the levels of peripartum dissociation and P-PTSD. Peripartum dissociation was positively associated with P-PTSD, and sense of control during birth was negatively associated with P-PTSD, indicating that higher levels of peripartum dissociation and lower levels of sense of control were associated with higher levels of P-PTSD. Finally, P-PTSD was negatively associated with maternal self-efficacy and maternal bonding, indicating that the higher the level of P-PTSD – the lower the levels of maternal self-efficacy and maternal bonding. Peripartum dissociation and sense of control during birth, both measured at T1, were negatively correlated, and maternal self-efficacy and maternal bonding, both measured at T2, were positively correlated.

In addition, the following significant indirect effects were found: a) The association between CM and maternal self-efficacy was mediated by a serial mediation of peripartum dissociation and P-PTSD, effect = −0.03, SE = 0.01, 95%CI[−0.06, −0.01], p = 0.005. b) The association between CM and maternal bonding was mediated by a serial mediation of peripartum dissociation and P-PTSD, effect = −0.03, SE = 0.02, 95%CI [−0.07, −0.01], p = 0.006.

Finally, since mode of delivery and post-partum depression were controlled for, they are not presented in Fig. 1. However, postpartum depression was negatively associated with maternal self-efficacy (effect = −0.44, p < 0.001) but not with maternal bonding (effect = −0.10, p = 0.17). Mode of delivery was not associated with either maternal self-efficacy (effect = 0.05, p = 0.23) or maternal bonding (effect =−0.5, p = 0.39).

Discussion

This longitudinal study examined a two-path model, according to which the associations between CM and maternal self-efficacy and maternal bonding are mediated by both peripartum dissociation and sense of control which led to P-PTSD, which in turn impaired emotional adjustment to motherhood. CM was associated with lower self-reported emotional adjustment to motherhood in survivors, 3 months postpartum. These effects were mediated by peripartum dissociation and P-PTSD, but not by sense of control during labor, and remained significant after controlling for important risk factors such as mode of delivery and postpartum-depression.

In our sample, while P-PTSD rates were similar to the previously reported prevalence (Ayers 2004; Grekin and O’Hara 2014), CM self-reported rates were somewhat lower compared to previous reports (Finkelhor et al. 2015; Stoltenborgh et al. 2015). This difference might be attributed to the sensitive post-partum period during which women were asked about CM.

Our findings emphasize the role of peripartum dissociation, measured within 48-h postpartum, on the development of P-PTSD 3-months postpartum. Although perinatal dissociation is common among CM survivors (Leeners et al. 2016; Lev-Wiesel and Daphna-Tekoah 2010), its relation to P-PTSD has been questioned. Our findings are in line with reports that indicated that peripartum dissociation is a risk factor for P-PTSD (Ayers et al. 2016; Olde et al. 2005; Thiel and Dekel 2020), specifically among CM survivors (Lev-Wiesel and Daphna-Tekoah 2010), and contradict former studies that found no such association (Goutaudier et al. 2012; Vossbeck-Elsebusch et al. 2014). However, it should be noted that most research on the association between peripartum dissociation and P-PTSD is limited by cross-sectional design (Thiel and Dekel 2020), secondary analysis of data (Choi and Seng 2016), small sample sizes (Goutaudier et al. 2012; Olde et al. 2005) or retrospective assessment of peripartum dissociation 1–6 months postpartum (Lev-Wiesel and Daphna-Tekoah 2010; Thiel and Dekel 2020; Vossbeck-Elsebusch et al. 2014). These limitations risk recall bias related to P-PTSD, depression, or impaired bonding outcomes.

In our sample, CM was not associated with sense of control during childbirth. Qualitative research with CM survivors has found that loss of control during birth may mirror the loss of control during CM (Chamberlain et al. 2019; Montgomery 2013) and that retaining control and building a trusting relationship with maternity care providers during childbirth is of critical importance to their sense of empowerment and safety (Millar et al. 2021; Montgomery 2013). Despite the beneficial effects of obstetric care on both the woman and the baby’s health, heightened obstetric care during childbirth may reduce the woman’s sense of choice and control (Johanson 2002), limit the capacity to experience body agency (Reiger and Dempsey 2006) and evoke lack of control (Morris et al. 2014; Rubin and Steinberg 2011). Therefore, sense of control during childbirth might be related more to circumstantial characteristics (i.e., mode of delivery and the relationship with maternity care providers) than to CM history.

Although our findings do not support the suggestion that sense of control during childbirth has a mediating role between CM and adjustment to motherhood, we have shown that lower sense of control is related to P-PTSD. The latter findings are in line with previous reports (Adewuya et al. 2006; Elmir et al. 2010; Soet et al. 2003) and with studies indicating that feeling out of control is a key characteristic of traumatic birth experiences (Elmir et al. 2010). We also found lower levels of sense of control to be related to higher levels of peripartum dissociation. Since both control and dissociation were measured at T1, a causal effect cannot be determined. However, we suggest a vicious cycle in which feeling out of control evokes dissociative reactions, and becoming dissociated makes women feel increasingly out of control.

Finally, we observed that mothers with higher P-PTSD symptoms reported lower levels of maternal bonding, even after controlling for postpartum depression. Evidence for an association between P-PTSD and mother-infant bonding have been contradictory (Cook et al. 2018). A recent systematic review (Van Sieleghem et al. 2022) suggested a negative association between P-PTSD and mother-infant attachment and child behavior. However, the authors emphasized that confounding factors may explain this association, as well as the high comorbidity of P-PTSD with postpartum depression (Ertan et al. 2021), as postpartum depression alone or comorbid with PTSD was found to be associated with impaired bonding (Muzik et al. 2013; Seng et al. 2013). Our results emphasize the specific role of P-PTSD in impaired maternal adjustment.

Limitations and strengths

There are several limitations to this study. First, our findings are based on self-report questionnaires which did not provide precise medical diagnoses of P-PTSD, nor a direct clinical evaluation of maternal adjustment through observation of mother-infant interactions. However, because the study sought to capture women's perceptions of their own experiences, the utilization of self-report questionnaires for evaluation of CM, sense of control and dissociation was a strength. Furthermore, we lacked pre-delivery comparative data regarding participants’ baseline mental health, predelivery dissociation, PTSD and depression, as well as past or current therapy. Due to ethical considerations, CM data were collected at T2, thus reports may have been influenced by other parameters such as P-PTSD or depression measured at that point. Exclusion of women in critical conditions or with negative outcomes, may have led to a selection bias. Moreover, as the study used a convenience sample recruitment from a single medical center (though a large public hospital serving an economically and socially diverse community), there is an understandable threat to external validity. Additionally, the majority of the participants were Jewish, and we lack data on the race and ethnicity, therefore generalization of our results to other religious or ethnical groups should be with caution. Finally, the response rate at T2 was 67.05% of the original cohort, however a series of comparisons between T2 participants and dropouts reduced the threat of selection bias attrition.

The study’s longitudinal design, measurement of peripartum dissociation within 48 h postpartum, the relatively large cohort, the general similarity between T2 participants and dropouts and the control for recognized risk factors, all contribute to the strengths of our findings.

Implications

While CM is common among women and has significant implications for labor and for the post-partum period including increased risk for P-PTSD and impaired maternal adjustment, it is also under-diagnosed and often not disclosed. Perinatal caregivers should be trained to routinely implement a trauma-informed approach in obstetric care, including communication skills aimed at strengthening women’s sense of control, and recognition and response to signs of distress during childbirth including dissociative reactions.

Future studies should assess whether routine implementation of such an approach may decrease the incidence of P-PTSD and improve maternal emotional adjustment following childbirth.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author (I.B). The data are not publicly available due to restrictions (containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants).

References

Adewuya AO, Ologun YA, Ibigbami OS (2006) Post-traumatic stress disorder after childbirth in Nigerian women: prevalence and risk factors. BJOG 113(3):284–288. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00861.x

Arens AM, Gaher RM, Simons JS, Dvorak RD (2014) Child Maltreatment and Deliberate Self-Harm: A Negative Binomial Hurdle Model for Explanatory Constructs. Child Maltreat. 19:168–177. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559514548315

Ayers S (2004) Delivery as a traumatic event: Prevalence, risk factors, and treatment for postnatal posttraumatic stress disorder. Clin Obstet Gynecol 47:552–567. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.grf.0000129919.00756.9c

Ayers S, Bond R, Bertullies S, Wijma K (2016) The aetiology of post-traumatic stress following childbirth: a meta-analysis and theoretical framework. Psychol Med 46:1121–1134. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715002706

Banyard VL, LaPlant LE (2002) Exploring links between childhood maltreatment and empowerment. J Community Psychol 30:687–707. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.10026

Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD et al (2003) Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl 27:169–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0

Berry KM, Rutledge CM (2016) Factors that influence women to disclose sexual assault history to health care providers. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 45(4):553–564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogn.2016.04.0

Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, Witte TK, Domino JL (2015) The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation. J Trauma Stress 28:489–498. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22059

Bovin MJ, Marx BP, Weathers FW et al (2016) Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist for diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders-fifth edition (PCL-5) in veterans. Psychol Assess 28:1379–1391. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000254

Brenner I, Ben-Amitay G (2015) Sexual revictimization: the impact of attachment anxiety, accumulated trauma, and response to childhood sexual abuse disclosure. Violence Vict 30(1):49–65. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.vv-d-13-00098

Carter J, Bick D, Gallacher D, Chang YS (2022) Mode of birth and development of maternal postnatal post-traumatic stress disorder: a mixed-methods systematic review and meta-analysis. Birth 49:616–627. https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12649

Chamberlain C, Ralph N, Hokke S et al (2019) Healing The Past By Nurturing The Future: a qualitative systematic review and meta-synthesis of pregnancy, birth and early postpartum experiences and views of parents with a history of childhood maltreatment. PLoS ONE 14(12):e0225441. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0225441

Choi KR, Seng JS (2016) Predisposing and precipitating factors for dissociation during labor in a cohort study of posttraumatic stress disorder and childbearing outcomes. J Midwifery Womens Health 61:68–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmwh.12364

Christie H, Talmon A, Schäfer SK et al (2018) The transition to parenthood following a history of childhood maltreatment: a review of the literature on prospective and new parents’ experiences. Eur J Psychotraumatol 8(Suppl 7):1492834. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2018.1492834

Cook N, Ayers S, Horsch A (2018) Maternal posttraumatic stress disorder during the perinatal period and child outcomes: a systematic review. J Affect Disord 225:18–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.07.045

Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R (1987) Detection of postnatal depression: development of the 10-item edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Br J Psychiatry 150:782–786. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.150.6.782

Cronin-Fisher V, Timmerman LM (2022) Redefining “healthy mom, healthy baby”: making sense of traumatic birth stories through relational dialectics theory. West J Commun 87:1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10570314.2022.2118548

Czarnocka J, Slade P (2000) Prevalence and predictors of post-traumatic stress symptoms following childbirth. Br J Clin Psychol 39:35–51. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466500163095

Dekel S, Stuebe C, Dishy G (2017) Childbirth induced posttraumatic stress syndrome: a systematic review of prevalence and risk factors. Front Psychol 8:560. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00560

Do HP, Vo TV, Murray L et al (2022) The influence of childhood abuse and prenatal intimate partner violence on childbirth experiences and breastfeeding outcomes. Child Abuse Negl 131:105743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105743

Elmir R, Schmied V, Wilkes L, Jackson D (2010) Women’s perceptions and experiences of a traumatic birth: a meta-ethnography: women’s perceptions and experiences of a traumatic birth. J Adv Nurs 66:2142–2153. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05391.x

Ertan D, Hingray C, Burlacu E, Sterlé A, El-Hage W (2021) Post-traumatic stress disorder following childbirth. BMC Psychiatry 21:155. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03158-6

Finkelhor D, Turner HA, Shattuck A, Hamby SL (2015) Prevalence of childhood exposure to violence, crime, and abuse: results from the National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence. JAMA Pediatr 169:746–754. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0676

Friedman LS, Samet JH, Roberts MS, Hudlin M, Hans P (1992) Inquiry about victimization experiences. A survey of patient preferences and physician practices. Arch Intern Med 152(6):1186–1190. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.152.6.1186

Garthus-Niegel S, Ayers S, Martini J, von Soest T, Eberhard-Gran M (2017) The impact of postpartum post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms on child development: a population-based, 2-year follow-up study. Psychol Med 47:161–170. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329171600235X

Glasser S, Barell V, Shoham A et al (1998) Prospective study of postpartum depression in an Israeli cohort: prevalence, incidence and demographic risk factors. J J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 19(3):155–164. https://doi.org/10.3109/01674829809025693

Goutaudier N, Séjourné N, Rousset C, Lami C, Chabrol H (2012) Negative emotions, childbirth pain, perinatal dissociation and self-efficacy as predictors of postpartum posttraumatic stress symptoms. J Reprod Infant Psychol 30:352–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2012.738415

Greene CA, Haisley L, Wallace C, Ford JD (2020) Intergenerational effects of childhood maltreatment: a systematic review of the parenting practices of adult survivors of childhood abuse, neglect, and violence. Clin Psychol Rev 80:101891. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101891

Grekin R, O’Hara MW (2014) Prevalence and risk factors of postpartum posttraumatic stress disorder: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 34:389–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.05.003

Hodnett ED, Simmons-Tropea DA (1987) The labour agentry scale: psychometric properties of an instrument measuring control during childbirth. Res Nurs Health 10:301–310. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.4770100503

Horesh D, Nukrian M, Bialik Y (2018) To lose an unborn child: post-traumatic stress disorder and major depressive disorder following pregnancy loss among Israeli women. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 53:95–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2018.02.003

Hu LT, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling 6(1):1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Johanson R (2002) Has the medicalisation of childbirth gone too far? BMJ 324:892–895. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.324.7342.892

Kestler-Peleg M, Shamir-Dardikman M, Hermoni D, Ginzburg K (2015) Breastfeeding motivation and self-determination theory. Soc Sci Med 144:19–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.09.006

Kline RB (1998) Software Review: Software programs for structural equation modeling: amos, EQS, and LISREL. J Psychoeduc Assess 16:343–364. https://doi.org/10.1177/073428299801600407

Leeners B, Görres G, Block E, Hengartner MP (2016) Birth experiences in adult women with a history of childhood sexual abuse. J Psychosom Res 83:27–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.02.006

Lev-Wiesel R, Daphna-Tekoah S (2010) The role of peripartum dissociation as a predictor of posttraumatic stress symptoms following childbirth in Israeli Jewish women. J Trauma Dissociation 11:266–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299731003780887

Lev-Wiesel R, Chen R, Daphna-Tekoah S, Hod M (2009a) Past traumatic events: are they a risk factor for high-risk pregnancy, delivery complications, and postpartum posttraumatic symptoms? J Womens Health 18:119–125. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2008.0774

Lev-Wiesel R, Daphna-Tekoah S, Hallak M (2009b) Childhood sexual abuse as a predictor of birth-related posttraumatic stress and postpartum posttraumatic stress. Child Abuse Negl 33:877–887. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.05.004

Little RJA (1988) A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. J Am Stat Assoc 83:1198–1202. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1988.10478722

MacDonald K, Thomas ML, Sciolla AF et al (2016) Minimization of childhood maltreatment Is common and consequential: results from a large, multinational sample using the childhood trauma questionnaire. PLoS ONE 11:e0146058. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0146058

Martini J, Asselmann E, Weidner K, Knappe S, Rosendahl J, Garthus-Niegel S (2022) Prospective associations of lifetime post-traumatic stress disorder and birth-related traumatization with maternal and infant outcomes. Front Psychiatry 13:842410. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.842410

Millar HC, Lorber S, Vandermorris A et al (2021) “No, You Need to Explain What You Are Doing”: Obstetric care experiences and preferences of adolescent mothers with a history of childhood trauma. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 34(4):538–545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2021.01.006

Montgomery E (2013) Feeling safe: a metasynthesis of the maternity care needs of women who were sexually abused in childhood. Birth 40(2):88–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12043

Morris KL, Goldenberg JL, Heflick NA (2014) Trio of terror (pregnancy, menstruation, and breastfeeding): an existential function of literal self-objectification among women. J Pers Soc Psychol 107:181–198. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036493

Muzik M, Bocknek EL, Broderick A et al (2013) Mother–infant bonding impairment across the first 6 months postpartum: the primacy of psychopathology in women with childhood abuse and neglect histories. Arch Womens Ment Health 16:29–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-012-0312-0

Muzik M, Morelen D, Hruschak J, Rosenblum KL, Bocknek E, Beeghly M (2017) Psychopathology and parenting: an examination of perceived and observed parenting in mothers with depression and PTSD. J Affect Disord 207:242–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.08.035

O’Boyle EH Jr, Williams LJ (2011) Decomposing model fit: measurement vs. theory in organizational research using latent variables. J Appl Psychol 96:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020539

O’Donovan A, Alcorn KL, Patrick JC, Creedy DK, Dawe S, Devilly GJ (2014) Predicting posttraumatic stress disorder after childbirth. Midwifery 30:935–941. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2014.03.011

Oh W, Muzik M, McGinnis EW, Hamilton L, Menke RA, Rosenblum KL (2016) Comorbid trajectories of postpartum depression and PTSD among mothers with childhood trauma history: course, predictors, processes and child adjustment. J Affect Disord 200:133–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.04.037

Olde E, van der Hart O, Kleber RJ, van Son MJ, Wijnen HA, Pop VJ (2005) Peritraumatic dissociation and emotions as predictors of PTSD symptoms following childbirth. J Trauma Dissociation 6:125–142. https://doi.org/10.1300/J229v06n03_06

Ozer EJ, Best SR, Lipsey TL, Weiss DS (2003) Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 129:52–73. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.52

Paivio SC, Cramer KM (2004) Factor structure and reliability of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in a Canadian undergraduate student sample. Child Abuse Negl 28:889–904. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.01.011

Reiger K, Dempsey R (2006) Performing birth in a culture of fear: an embodied crisis of late modernity. Health Sociol Rev 15:364–373. https://doi.org/10.5172/hesr.2006.15.4.364

Rubin LR, Steinberg JR (2011) Self-objectification and pregnancy: are body functionality dimensions protective? Sex Roles 65:606–618. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-9955-y

Sar V (2011) Epidemiology of dissociative disorders: an overview. Epidemiol Res Int Article ID 404538. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/404538

Seng JS, Sperlich M, Low LK, Ronis DL, Muzik M, Liberzon I (2013) Childhood abuse history, posttraumatic stress disorder, postpartum mental health, and bonding: a prospective cohort study. J Midwifery Womens Health 58:57–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1542-2011.2012.00237.x

Sexton MB, Hamilton L, McGinnis EW, Rosenblum KL, Muzik M (2015) The roles of resilience and childhood trauma history: main and moderating effects on postpartum maternal mental health and functioning. J Affect Disord 174:562–568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.12.036

Shalev AY, Peri T, Canetti L, Schreiber S (1996) Predictors of PTSD in injured trauma survivors: a prospective study. Am J Psychiatry 153:219–225. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.153.2.219

Soet JE, Brack GA, DiIorio C (2003) Prevalence and predictors of women’s experience of psychological trauma during childbirth. Birth 30:36–46. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-536X.2003.00215.x

Stoltenborgh M, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Alink LRA, van IJzendoorn MH (2015) The prevalence of child maltreatment across the globe: review of a series of meta-analyses. Child Abuse Rev 24:37–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2353

Taylor A, Atkins R, Kumar R, Adams D, Glove V (2005) A new Mother-to-Infant Bonding Scale: links with early maternal mood. Arch Women’s Ment Health 8:45–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-005-0074-z

Thiel F, Dekel S (2020) Peritraumatic dissociation in childbirth-evoked posttraumatic stress and postpartum mental health. Arch Womens Ment Health 23:189–197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-019-00978-0

Van Sieleghem S, Danckaerts M, Rieken R et al (2022) Childbirth related PTSD and its association with infant outcome: a systematic review. Early Hum Dev 174:105667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2022.105667

Vossbeck-Elsebusch AN, Freisfeld C, Ehring T (2014) Predictors of posttraumatic stress symptoms following childbirth. BMC Psychiatry 14:200. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-200

Williams K, Moehler E, Kaess M, Resch F, Fuchs A (2022) Dissociation links maternal history of childhood abuse to impaired parenting. J Trauma Dissociation 23(1):37–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2021.1934938

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

• The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Shamir-Assaf Harofeh Medical center, Zrifin, Israel.

• We hereby affirm that the material contained in the manuscript has not been published, has not been submitted, or is not being submitted elsewhere for publication.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

Anna Padoa:

- royalties from Springer Editors

- Speaker Honorarium from Pierre Fabre

All other authors have nothing to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Brenner, I., Ginzburg, K., Golan, A. et al. Peripartum dissociation, sense of control, postpartum posttraumatic stress disorder and emotional adjustment to motherhood in adult survivors of childhood maltreatment. Arch Womens Ment Health 27, 127–136 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-023-01379-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-023-01379-0