Abstract

Common wisdom suggests that cross-holdings can lead to significant output contraction, and thus hurt consumers. On the contrary, we demonstrate that cross-holdings may increase industry output and benefit consumers in an asymmetric Cournot oligopoly with the presence of a welfare-maximizing tax/subsidy policy. The government will strategically use the tax/subsidy policy to regulate the market outcomes in anticipation of the adverse effect of cross-holdings, which could raise industry output and benefit consumers in certain situations depending on the cost distributions and cross-holding structures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Cross-holding, which entitles the acquiring firm to non-controlling ownership in the acquired firm, is very common in a wide range of industries (Alley 1997; Dietzenbacher et al. 2000; Gilo et al. 2006; Trivieri 2007; Brito et al. 2014). This increasing trend of cross-holding activities has led competition authorities to assess the anti-competitive effects of such acquisitions.Footnote 1 However, there is a vivid debate on this issue. In Europe, it is widely discussed whether or not to extend EU merger control to cover cross-holdings, but the anti-competitive effects of cross-holdings have not been confirmed so far (European Commission 2014).Footnote 2

Common wisdom in the literature is that cross-holdings hurt consumers because the output market becomes more concentrated. The reason, as argued in Reynolds and Snapp (1986), is that the acquiring firm is induced to take into consideration the effect of its output decision on the acquired firm’s profit. This consideration makes the acquiring firm compete less aggressively by reducing its production, and the equilibrium industry output (price) is thus reduced (raised). Thus, cross-holdings generate a consumer-hurting effect. Since then a growing literature has followed up on the work of Reynolds and Snapp (1986) to support the theory of harm, including Flath (1992), Dietzenbacher et al. (2000), Liu et al. (2018), and Ma and Zeng (2022), etc.Footnote 3 By introducing cost asymmetry into the homogeneous Cournot model, Farrell and Shapiro (1990) and Ma et al. (2021) demonstrate that cross-holding could benefit social welfare when a high-cost firm increases its ownership in a low-cost firm. In addition, in a Cournot duopoly, Fanti (2015) shows that cross-holding may raise social welfare when the solely-owned firm is less efficient than the other (cross-held) firm and the market size is not too large. The reason of welfare-improving lies in the increased market production efficiency due to output redistribution. But importantly, industry output always decreases, and then cross-holding hurts consumers.Footnote 4 However, the evidence does not always support this view. In Levy (2013) and European Commission (2014), there are a number of cases in which cross-holdings do not necessarily lead to anti-competitive outcomes.

The literature on cross-holdings generally ignores policies by the government.Footnote 5 Indeed, governments may use taxation to reduce the distortion created by imperfectly competitive product market. In this paper, we study whether and the circumstances under which the consumers could be harmed or benefited by cross-holdings in an asymmetric Cournot oligopoly with the consideration of a welfare-maximizing tax/subsidy policy before production. It is important to emphasize that we aim to focus on the effect of cross-holdings on consumer surplus (i.e., industry output and price) rather than social welfare in Farrell and Shapiro (1990) and Ma et al. (2021). The reason for us to focus on consumer surplus is that it is the most common welfare standard used by competition authorities (see Vergé 2010; Gassler 2018; Hu et al. 2022; Shelegia and Spiegel 2022; etc.). For example, the consumer surplus standard is a guiding principle of competition policy in the U.S., the EU, and the UK (see OECD 2012, p. 26–27). Therefore, investigating the outcome for consumer surplus is an important factor, as it yields significant antitrust implications. Our primary research question is: do cross-holdings always reduce (increase) industry output (price) and therefore hurt consumers?

The welfare-maximizing tax/subsidy policy provides the government with one effective instrument to achieve its objective of welfare maximization, which could generate different welfare implications. In an asymmetric oligopoly with n efficient firms and m inefficient firms, we consider four different cross-holding structures: (i) cross-holdings among efficient firms; (ii) cross-holdings among inefficient firms; (iii) efficient firms hold ownership shares in inefficient firms; and (iv) inefficient firms hold ownership shares in efficient firms.Footnote 6 We show that the government will strategically use tax/subsidy policy to regulate the market in anticipation of the adverse effect of cross-holdings. As cross-holdings increase, the government may tend to reduce taxes or increase subsidies in many cases. It turns out that cross-holdings may increase industry output and benefit consumers in the presence of the tax/subsidy policy, depending on the cost distributions and cross-holding structures. The finding of consumer-benefiting cross-holdings is very important for competition authorities to develop sound antitrust policies.

Two other papers in the literature of horizontal cross-holdings demonstrate that cross-holdings could benefit consumers. Ghosh and Morita (2017) consider knowledge transfer in an asymmetric Cournot oligopoly in which an efficient firm holds ownership shares in one of the inefficient rivals. Although cross-holding reduces industry output, the accompanied knowledge transfer improves production efficiency and thus raises industry output. Hence, an endogenously determined cross-holding in this model could improve industry output in a range of parameterizations. López and Vives (2019) introduce cost-reducing R &D investment with spillovers into a Cournot oligopoly with cross-holdings. The authors show that when spillovers are sufficiently large, some overlapping ownership may actually increase social welfare and may even be consumer welfare-enhancing. Obviously, the mechanisms in these two papers are significantly different from ours. In this paper, we demonstrate that the tax/subsidy policy is a significant and non-negligible factor for the competitive effects of cross-holdings. With the presence of endogenous tax/subsidy policy, cross-holdings could benefit consumers even if there are no innovation, knowledge transfer (or cost synergy), or firm entry. Our focus in this paper is cross-holdings in horizontal markets. With the presence of upstream firms, downstream cross-holding affects not only final production but also input prices. And reduced input prices may indirectly expand industry output to a greater extent than the output reduction directly induced by cross-holding (Shuai et al. 2023), which therefore, benefits consumers and social welfare. Similar arguments are provided in Fanti (2016a, 2016b) which study the effects of downstream cross-ownership with the consideration of pair-wise exclusive vertical relationships.Footnote 7

Another important paper by Liu et al. (2015) studies the merger incentive in a symmetric Cournot oligopoly with consumption externality and a strategic unit tax policy. The authors show that (i) a unit tax policy increases the incentive for a horizontal merger, and (ii) a horizontal merger with a sufficiently large number of inside firms could benefit consumers. It is important to note that there are essential differences between Liu et al. 2015 and our paper. Firstly, Liu et al. (2015) focus on mergers with full controlling acquisitions which reduce the number of active firms. But we consider cross-holdings with partial non-controlling acquisitions, which allow independent decisions by all engaged firms. This is also the main argument why merger control rules are not allowed to be extended to cover cross-holdings in most countries.Footnote 8 Secondly, the authors propose a model of symmetric Cournot firms and show that a horizontal merger may raise industry output and benefit consumers. But the consumer-benefiting merger requires a sufficient number of merged firms (i.e., a sufficient reduction in the number of firms) and a moderate marginal social cost of the public fund. By contrast, we consider asymmetric firms (efficient firms vs. inefficient firms) in our model, which are all active in the market. We further consider four different cross-holding structures and show that cross-holdings may benefit consumers depending on the cost distributions and cross-holding structures. To some extent, our results are much richer, and more clearly illustrate how the effects of tax/subsidy policy and cross-holdings interact and balance.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 builds up the basic model with asymmetric Cournot firms. Section 3 presents the analysis and main findings. Section 4 discusses the robustness of the main results under a different tax scheme and mode of competition. Section 5 concludes.

2 The model

We consider an asymmetric oligopoly with \(n\ge 1\) efficient firms with marginal cost d, and \(m\ge 1\) inefficient firms with marginal cost c, where \(0\le d<c\). All firms produce homogeneous products under Cournot competition. The inverse market demand function is \(P = a-Q\), where P is market price, and \(Q =\Sigma _{i=1}^n q_i +\Sigma _{j=1}^m q_j\) is industry output. We use \(q_i\) and \(q_j\) to denote the output of each efficient firm i, and each inefficient firm j, respectively.

Firms in the market are assumed to engage in cross-holdings. Following the literature, we assume throughout the paper that cross-holdings between firms are passive in the sense that each firm is entitled to a share of its target’s profit but not decision making (see Farrell and Shapiro 1990; Flath 1992; Gilo et al. 2006; Ghosh and Morita 2017), i.e., \(0<\delta <1/2\). We consider the following four different cross-holding structures:Footnote 9

-

Case 1.

efficient firms hold symmetric ownership shares in each others: each efficient firm i acquires a share, \(\delta /(n-1)\), of ownership in each efficient rival firm.

-

Case 2.

inefficient firms hold symmetric ownership shares in each others: each inefficient firm j acquires a share, \(\delta /(m-1)\), of ownership in each inefficient rival firm.

-

Case 3.

efficient firms hold symmetric ownership shares in inefficient firms: each efficient firm i holds a share, \(\delta /n\) in each inefficient firm j.

-

Case 4.

inefficient firms hold symmetric ownership shares in efficient firms: each inefficient firm j holds a share, \(\delta /m\) in each efficient firm i.

In all four cases, each acquiring firm holds a total fraction of ownership, \(\delta\), in acquired firms. And this fractional ownership is symmetrically distributed among acquired firms.Footnote 10 Indeed, our results continue to hold in a more general case in which the assumption of symmetric distribution of acquired shares fails as long as the total fraction of ownership held by others are the same for each acquired firm (see footnote 17 and 19).

As is known, another stylized fact is the existence of taxation in oligopolistic sectors. To be distinct from the cross-holding literature that does not consider government policies, we consider the case that the welfare-maximizing government imposes an ad valorem tax \(\tau\) on each firm (Anderson et al. 2001; Wang and Zhao 2009). Following the literature, the tax rate, \(\tau\), is assumed throughout to be strictly less than unit, i.e., \(\tau <1\). Otherwise, the profits are negative for firms and therefore they will not produce in equilibrium. Further, it could be a tax when \(\tau\) is positive and a subsidy when \(\tau\) is negative. The producer price is thus \((1-\tau )P\).

Note that our aim is not to endogenize the ownership acquisitions. Rather, we aim to re-examine the effect on consumer surplus of a small increase in the ownership of acquisition \(\delta\).Footnote 11 Without the presence of a welfare-maximizing tax policy, Farrell and Shapiro (1990) and Ma et al. (2021) study the effects of increasing ownership slightly on profits, industry performance, and market concentration. The authors find that increasing ownership reduces industry output and therefore hurts consumers in different contexts.Footnote 12 Our paper, as a direct contrast, challenges the result on consumer surplus with the introduction of a welfare-maximizing tax policy.

The timeline of the game is as follows. In stage 1, the government determines \(\tau\) to maximize social welfare. In stage 2, all firms compete in a Cournot fashion. We assume throughout this paper that all firms are active in production after cross-holdings. As usual, we solve this two-stage game with backward induction.

3 The analysis and results

To illustrate how cost asymmetry affects the outcomes of government regulation, we present the case of symmetric firms as a benchmark. After that, we incorporate cost asymmetry between firms into the model to clearly explain how it makes significant differences under different cross-holding structures.

3.1 Benchmark case: symmetric Cournot firms

The \(n+m\) firms are identical with marginal cost c and engage in symmetric cross-holdings. Assume that all firms produce a positive quantity in the (unique) Cournot equilibrium. In the second stage, each firm i, \(i=1, 2, \ldots , n+m\), determines \(q_i\) to maximize its profit

Solving the first-order conditions leads to the equilibrium quantities in the second stage as

The second-order conditions for the maximization problems are satisfied. To ensure positive outputs for the firms, we assume \(\tau <{(a-c)}/{a}\).

In the first stage, the government chooses \(\tau\) to maximize social welfare, i.e., the sum of industry profit, consumer surplus, and tax revenue:Footnote 13

By solving the first-order condition, we obtain the tax rate in equilibrium as

The second-order condition is assumed to be satisfied. Simple calculations lead to that

Footnote 14 which indicates that the government provides subsidies to firms in equilibrium, and the rate of subsidies increases with \(\delta\).Footnote 15 Simple calculations lead to

Proposition 1

When firms are symmetric in technology and hold symmetric shares in each other, an increase in \(\delta\) does not affect the industry output in equilibrium.

The strategic tax/subsidy policy considered here provides the government with one instrument to achieve its objective of welfare maximization, which is very effective when firms are identical in technology. Intuitively, increasing cross-holdings induces firms to compete less aggressively by reducing production. Hence, the government strategically increases subsidies to encourage the production of firms. With a well-designed subsidy, the government could realize the desirable result of perfect competition for any degree of cross-holdings.Footnote 16

By (1), we obtain the profit for each firm i as

Then we have

which confirms the motivations to increase the degree of cross-holdings jointly. This inequality implies that the profit of each firm is maximized when \(\delta\) reaches the maximum possible value in footnote 15. As the market becomes more concentrated due to an increase in cross-holdings, each firm receives a higher subsidy from the government and then realizes a higher profit.

However, when firms are asymmetric in technology, there exist competition among efficient firms, competition among inefficient firms and competition between efficient and inefficient firms, while only one kind of competition exists in the case of symmetric firms. Hence, the asymmetric-firms case may yield different implications because the government has to take all the factors into consideration.

3.2 Asymmetric Cournot firms

In this section, we examine whether consumers can benefit from cross-holdings with a higher industry output and a lower price when firms are asymmetric in production technology. We consider the following cases.

3.3 Case 1: Cross-holdings between efficient firms

In the second stage, each firm simultaneously chooses the optimal quantity to achieve profit maximization. The profit for each efficient firm is

where the first term on the RHS denotes firm i’s operating earnings, and the second term denotes its financial interests earned through ownership acquisitions.Footnote 17 Straightforwardly, the profit for each inefficient outside firm is

Solving the first-order conditions leads to the equilibrium quantities in the second stage as

The second-order conditions are satisfied. Thus, the industry output is given by

For any given tax rate, an increase in \(\delta\) reduces \(q_i\), but raises \(q_j\). The industry output decreases as a result. Hence, cross-holdings make consumers worse off under exogenous taxation. This result is well known in the literature (Farrell and Shapiro 1990). Intuitively, cross-holdings build up a financial relationship between efficient firms, and thus induces them to compete less aggressively by reducing production. All outside firms respond to raise production as a result.

In the first stage, the government chooses \(\tau\) to maximize social welfare, which is

By solving the first-order condition, we obtain the tax rate in equilibrium as

where \(H_1(\delta )\!=\!(1+m+(1\!-\!\delta )n)\left( (1\!-\!\delta )(1\!+\!m)d^2n\!-\!2(1\!-\!\delta )d c n m\!+\!(1\!+\!(1\!-\!\delta )n)c^2\,m\right) .\) The second-order condition for the maximization problem is assumed to be satisfied.

Lemma 1

\(\tau ^{1*}|_{\delta =0}<0\) when \(T_2< a < T_1\), and \(\tau ^{1*}|_{\delta =0}\in [0, 1)\) when \(a \le T_2\), where

further, \(\partial \tau ^{1*}/\partial \delta <0\) when \(d/c<m/(1+m)\). The sign of \(\partial \tau ^{1*}/\partial \delta\) is ambiguous (can be either positive or negative) when \(d/c>m/(1+m)\).

Lemma 1 indicates that the equilibrium tax can be either positive or negative without cross-holdings, which depends on the market size. That is, the government may either introduce a tax (when demand is small) or a subsidy (when demand is relatively large) to firms. In anticipation of the negative effect of cross-holdings on industry output and market efficiency, the government strategically reduces \(\tau\) to regulate the market outcomes when the low-cost firms are very efficient, aiming to achieve social welfare maximization. That is, as \(\delta\) increases, the government may tend to reduce taxes levied on firms or raise subsidies to firms.

Incorporating the equilibrium tax rate, we get the equilibrium quantities for all firms. By (9), the equilibrium industry output is

where \(D_1= c^2\,m (1+n (1-\delta ))-2 c d m n (1-\delta )+ d^2 n (m+1) (1-\delta ).\) We next examine how consumer surplus changes with a higher \(\delta\). Differentiating \(Q^{1*}\) with respect to \(\delta\) leads to

The following results follow straightforwardly from (13).

Proposition 2

In case 1, an increase in \(\delta\) benefits consumers when \(d/c<m/(1+m)\). Otherwise, it hurts consumers.

The literature following Reynolds and Snapp (1986) believes that cross-holdings create market concentration, and lead to a reduction in industry output and consumer surplus, which therefore results in a higher price and generates a main concern for both antitrust authorities and academics. This result is obtained without the consideration of strategic tax/subsidy policies. By contrast, we show that cross-holdings between efficient firms may unexpectedly raise industry output when these engaged firms are sufficiently efficient (i.e., exists large firm heterogeneity) with the consideration of strategic tax/subsidy policies.

The driving factor to our result is the strategic tax/subsidy policy by the government, which aims to correct market inefficiency due to the socially undesirable output shifting from engaged efficient firms towards outside inefficient firms. When efficient firms engage in cross-holdings, these firms produce less while outside inefficient firms produce more, which results in an inefficient production distribution. The total output decreases as a result. This anti-competitive effect of cross-holdings are identified in the literature. In anticipation of this, the government may reduce \(\tau\) to encourage production. This tax-reducing effect is positive to production. The resulting output expansion caused by government regulation dominates the well-known output reduction caused by cross-holdings when \(d/c<m/(1+m)\). As such, our results generate important insights for competition policy.

To end this section, we look at the joint profit of efficient firms to confirm the motivations to jointly increase \(\delta\). Straightforward calculations lead to

Even though the expressions are complicated, we can show that the derivative \(\partial (n\pi _i^*)/\partial \delta\) can be either positive or negative.Footnote 18 Under certain circumstances, efficient firms are motivated to increase cross-holdings. And if the condition in Proposition 2 is satisfied, increasing the degree of cross-holdings raises industry output and benefits consumers.

In the following example, we illustrate that increasing cross-holdings among efficient firms could be profitable for firms and benefit consumers.

Example 1

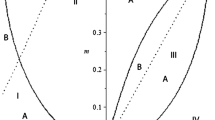

Consider \(a=100\), \(n=3\), \(m=4\), \(c=20\), \(d=9\). Standard calculations yield the equilibrium outcomes:

Any \(\delta \in (0, 1/2)\) would satisfy the constraints of \(\tau ^{1*}<1\), \(q_i^{1*}>0\), and \(q_j^{1*}>0\). Simple calculations yield \({\partial \tau ^{1*} }/{\partial \delta }<0\), holding for any \(\delta \in (0, 1/2)\). We have \(0<\tau ^{1*}<1 \text { when } 0< \delta < 0.3092,\) and \(\tau ^{1*}<0 \text { when } 0.3092< \delta < 0.5\). That is, increasing \(\delta\) induces the government to reduce the tax rate. The government levies taxes on firms when the degree of cross-holdings is small and provides subsidies to firms when that is large. The profit of each efficient firm is obtained as

which is positive for \(0<\delta <0.3703\) and is negative for \(0.3703<\delta <0.5\). This implies that the efficient firms have incentive to increase cross-holdings till \(\delta =0.3703\). Further, we have

Since \(d/c<m/(1+m)\), the condition in Proposition 2 is satisfied. Hence, increasing \(\delta\) raises industry output and thus benefit consumers.

3.4 Case 2: Cross-holdings between inefficient firms

By analogy, we can easily obtain the equilibrium outcomes when inefficient firms hold passive ownership in each other. A simple way to do this is to switch n and m with each other, and switch d and c with each other in case 1. It follows that cross-holdings in this case shift production from inefficient firms to efficient firms, which improves market efficiency. This is the major difference from that in case 1. The industry output decreases due to market concentration. As a result, the government strategically uses taxation as a tool to reduce the adverse effect of cross-holdings.

As in Lemma 1, we can derive the conditions for \(\tau ^{2*}|_{\delta =0}\) to be positive or negative. The two cutoffs can be written by switching m and n, c and d in \(T_1\) and \(T_2\), respectively. The distance between the two cutoffs is again \(cm+dn\). Further, we have \(\partial \tau ^{2*}/\partial \delta <0\), which holds when the assumptions on tax/subsidy and quantities are satisfied. That is, the government responds to reduce the tax levied on firms or raise the subsidy to firms to regulate the market outcomes.

In equilibrium, following (13) we have

Proposition 3

In case 2, an increase in \(\delta\) always benefits consumers.

As in case 1, there are two counteracting effects on industry output: the well-known anti-competitive effect due to an increase in cross-holdings, and a positive tax-reducing effect due to a reduction in tax rate. However, different from that in case 1, the firms that reduce production are those low-production inefficient firms. Meanwhile, the efficient firms respond to expand production. Hence, this anti-competitive effect is weaker in this case because of the above-mentioned efficient production distribution. It turns out that this weakened anti-competitive effect is dominated by the positive tax-reducing effect, which therefore benefits consumers.

We finally check whether the inefficient firms are motivated to increase shares in each other by examining how \(\delta\) influences \(\pi _j^{2*}\), which can be written as the mirror-image of \(\pi _i^{1*}\) in case 1. Similar to that in case 1, there exist certain circumstances under which inefficient firms have incentives to increase cross-holdings as illustrated in the following example.

Example 2

Consider \(a=100\), \(n=m=3\), \(c=45\), \(d=42\). Standard calculations yield the equilibrium outcomes:

Any \(\delta \in (0, 1/2)\) would satisfy the constraints of \(\tau ^{2*}<1\), \(q_i^{2*}>0\), and \(q_j^{2*}>0\). Simple calculations yield \({\partial \tau ^{2*} }/{\partial \delta }<0\) with \(\tau ^{2*}<0\), holding for any \(\delta \in (0, 1/2)\). That is, the government provides subsidies to firms and the level of which increases with the degree of cross-holdings, \(\delta\). The profit of each efficient firm is obtained as

which is positive when \(0<\delta <0.3375\), and is negative when \(0.3375<\delta <0.5\). This implies that the inefficient firms have incentives to increase cross-holding till \(\delta =0.3375\). Further, we have

which supports the finding in Proposition 3.

3.5 Case 3: Efficient firms hold shares in inefficient firms

In this case, all firms engage in cross-holdings. The profit for each efficient acquiring firm is

and the profit for each inefficient acquired firm is

Standard calculations by solving the first-order conditions yields thatFootnote 19

The second-order conditions are satisfied. The industry output is therefore

In the first stage, the government chooses \(\tau\) to maximize social welfare in (10), yielding the equilibrium tax rate as

where \(H_2(\delta )=c^2 m (n+1)-c d m (2 n+\delta )+d^2n (m+1)\). The second-order condition is assumed to be satisfied.

Lemma 2

\(\tau ^{3*}|_{\delta =0}<0\) when \(T_4< a < T_3\), and \(\tau ^{3*}|_{\delta =0}\in [0, 1)\) when \(a \le T_4\), where

further, the sign of \(\partial \tau ^{3*}/\partial \delta\) is ambiguous (can be either positive or negative).

Lemma 2 indicates that the government may respond to raise \(\tau\) when \(\delta\) increases, which is different from that in the previous two cases. The increase in \(\tau\) undoubtedly lowers the production of firms as we see below. The equilibrium industry output is

Differentiating \(Q^{3*}\) with respect to \(\delta\) leads to that

Proposition 4

In case 3, an increase in \(\delta\) hurts consumers.

In case 1 and 2 with outside firms, we identify the positive effect of tax policy on industry output and show that it could act as an effective tool to increase consumer surplus. However, when all firms are engaged in cross-holdings, things are very different. Firstly, the market becomes more concentrated with all firms involved. Furthermore, in case 3, the high-production efficient firms reduce production while those low-production inefficient firms expand production. The output reduction effect of cross-holding is more significant. Lastly, the government may raise taxes or reduce subsidies for firms. Apparently, the above three factors will lead to a reduction in industry output. Even when the government reduces taxes or increases subsidies to firms, the two above-mentioned negative effects will dominate the positive tax-reducing effect, which makes consumers worse off.

We have demonstrated that such cross-holdings are detrimental to industry output. Hence, our result suggest that the anti-trust authorities should pay greater attention to such cases. However, a natural question is: whether efficient firms have incentives to hold/increase shares in inefficient firms? In consideration of firms’ incentives to engage in cross-holdings, the joint profit of the involved firms must increase (see Farrell and Shapiro 1990; Ma et al. 2021; Shuai et al. 2023; etc). Let \(\Pi ^{3*}=n \pi _i^{3*} + m \pi _j^{3*}\) (see Appendix) denote the joint profit of involved firms. Straightforward calculations can yield the conditions for \(\partial \Pi ^{3*}/\partial \delta\) to be positive or negative. As before, these complicated conditions are omitted to avoid messy presentations. And we use the following example to illustrate that cross-holdings are jointly profitable for involved firms but are detrimental to consumers.

Example 3

Consider \(a=100\), \(n=m=3\), \(c=36\), \(d=28\). Standard calculations yield the equilibrium outcomes:

Any \(\delta \in (0, 1/2)\) would satisfy the constraints of \(\tau ^{3*}<1\), \(q_i^{3*}>0\), and \(q_j^{3*}>0\). It follows straightforwardly that \(\tau ^{3*}<0\) for any \(\delta \in (0, 1/2)\), and

That is, the government provides subsidies to firms without cross-holdings, but reduces subsidies as \(\delta\) increases. The industry output decreases as a result. In this case,

which is positive for \(0<\delta <0.36\) and is negative for \(0.36<\delta <0.5\). This implies that the firms have incentives to increase cross-holdings till \(\delta =0.36\). Such cross-holdings reduce industry output and hurt consumers.

3.6 Case 4: Inefficient firms hold shares in efficient firms

We can easily obtain the equilibrium outcomes in case 4 by switching n and m with each other, and switching d and c with each other in case 3. Following (20), we have

Proposition 5

In case 4, an increase in \(\delta\) benefits consumers when \(d/c>m/(m+1)\). Otherwise, it hurts consumers.

The result in Proposition 5 is in sharp contrast to that found in Proposition 4. The main reason is that the anti-competitive effect is weaker in this case because the firms that reduce production are those low-production inefficient firms while the efficient firms respond to expand production. Specifically, cross-holdings in this case shift production from inefficient firms toward efficient firms, which is socially desirable to the government. When the cost gap between efficient and inefficient firms is small, i.e., \(d/c>m/(m+1)\), the above positive effect on welfare due to output redistribution is not significant. To the government, increasing cross-holdings has “mainly negative” effect due to the reduction in industry output. Hence, the government strategically use the tax/subsidy policy to reverse this outcome. This positive policy effect turns out to dominate the anti-competitive effect, which therefore raises industry output. By contrast, when the cost gap between efficient and inefficient firms is large, i.e., \(d/c<m/(m+1)\), the above positive effect on welfare is significant, which could neutralize part of the negative effect from output reduction to the government. Hence, we do not have a strong positive policy effect that could dominate the anti-competitive effect.

As before, we use the following example to illustrate our finding in Proposition 5.

Example 4

Consider \(a=100\), \(n=m=3\), \(c=16\), \(d=14\). Standard calculations yield the equilibrium outcomes:

To ensure \(\tau ^{4*}<1\), \(q_i^{4*}>0\), and \(q_j^{4*}>0\), we need \(0<\delta <0.1717\). It follows straightforwardly that \(\tau ^{4*}<0\) in this case,

That is, the government always provides subsidies to firms. Furthermore, it tends to increase subsidies as \(\delta\) increases. The industry output increases as a result. In this case,

which is positive for \(0<\delta <0.1717\). This implies that the firms have incentives to increase cross-holdings till \(\delta =0.1717\). Since the condition, \(d/c>m/(m+1)\), in Proposition 5 is satisfied, such cross-holdings raise industry output and benefit consumers.

4 Further discussions

Before concluding the paper, we briefly discuss two extensions of the basic model in consideration of (i) unit tax and (ii) price competition. The detailed calculations for each of the following two cases are provided in the Appendix.

4.1 Unit taxation

In the basic model, we conduct the analysis with the consideration of strategic ad valorem taxation by the welfare-maximizing government. In the existing literature, another prevalent form of taxation is unit taxation, often referred to as specific taxation. It is widely acknowledged that unit (or specific) taxation and ad valorem taxation can yield distinct outcomes in the context of imperfect competition. Hence, it is interesting to assess the robustness of our main findings when considering strategic unit taxation.

Let us consider a scenario in which all firms are taxed at the same rate of t per unit of output, and reexamine the four cases in the basic model. Following the standard backward induction process, we find that an increase in the degree of cross-holdings harms consumers in cases 1 and 3 and benefits consumers in cases 2 and 4. The reasons for these outcomes are as follows: In cases 1 and 3 (and conversely in cases 2 and 4), under any given tax rate, efficient firms tend to reduce production, while inefficient firms increase production. The industry output decreases as a result. This essentially aligns with the consequence of reducing the number of efficient (inefficient) firms. The first instinct is that this will lead to a decrease in industry output due to reduced competition. However, following a similar line of reasoning as Dinda and Mukherjee (2014) which also consider unit taxation, we encounter an intriguing outcome in cases 2 and 4: engaging in cross-holdings actually leads to an increase in industry output and thus benefits consumers. This is because inefficient firms become less aggressive in production, thereby reducing competition between efficient and inefficient firms. Consequently, a welfare-maximizing government significantly increases subsidies to enhance market competition, resulting in higher industry output.

4.2 Price competition

The basic model focuses on Cournot competition. It would be interesting to explore the implications of cross-holdings when competition involves pricing in a market with differentiated products. A prior research paper authored by Fanti (2016b) demonstrates that the mode of competition has a significant impact on the welfare consequences of cross-holdings in a vertical market.Footnote 20 In this section, we assess the robustness of our previous findings by allowing firms to engage in price competition while offering differentiated products.

Following the IO literature on oligopoly with differentiated products, a representative consumer’s utility function is given by

which leads to the demand function for firm i’s product as

where y is the consumption of all other goods and \(\gamma \in (0, 1)\) measures the degree of product substitutability.

The standard backward induction process yields equilibrium results in the two stages; however, the expressions for equilibrium prices and quantities are highly complex, which obstructs a comprehensive analysis of welfare implications in a clear and concise manner. Consequently, for each case, we perform an extensive series of numerical simulations using Mathematica. Our simulations indicate that an increase in the degree of cross-holdings has adverse effects on consumers in cases 1 and 3, while benefiting consumers in cases 2 and 4. As we can observe, cross-holdings create anti-competitive effects for any given tax rate, which has a detrimental impact on consumers. However, the welfare-maximizing government can strategically employ taxation as a tool to devise appropriate remedies that benefit consumers. In the Bertrand model, prices are considered strategic complements. This is because when one firm opts to reduce prices, it incentivizes the other firm to follow suit for profitable outcomes. Especially in cases where efficient firms are encouraged to adopt less aggressive behaviors, such as in cases 1 and 3, this negative effect tends to be notably significant, consistently outweighing the positive effect arising from the taxation remedies.Footnote 21 In contrast, in cases 2 and 4, inefficient firms are motivated to conduct less aggressive practices, resulting in less substantial competition-related issues. The government’s tax remedies serve to mitigate the adverse effects of cross-holdings, ultimately leading to increased industry output.

5 Concluding remarks

It is believed in the literature that cross-holding leads to market concentration and hurts consumers by reducing industry output, which creates concerns for the antitrust authorities. Although there currently are no antitrust rules that can be reliably and effectively applied to curtail such anti-competitive effects, treatment of cross-holdings has gained increasing attention by antitrust authorities worldwide.

However, this view generally ignores the role of the government. As is know, another stylized fact is the existence of taxation in oligopolistic sectors with cross-holdings. Thus, a natural question arises: does the common wisdom that cross-holding decrease output and therefore hurt consumers still hold with the consideration of a welfare-maximizing tax/subsidy policy? We find that, with the presence of endogenous taxation by the government, cross-holdings could well increase industry output and reduce price in certain situations. Specifically, (i) when the low-cost firms are sufficiently efficient, increasing cross-holdings between efficient firms could benefit consumers; (ii) when the cost cap between firms are sufficient small, increasing cross-holdings in efficient firms by inefficient firms could benefit consumers; and (iii) increasing cross-holdings between inefficient firms always benefits consumers. These results are worthy of notice to both antitrust authorities and academics.

In this paper, we take the first step to study the welfare effects of cross-holdings under a welfare-maximizing tax/subsidy policy. To begin with, we make several simplifying assumptions for tractability, such as homogenous products, linear demand, and constant marginal costs. In the future, discussing the robustness of our main results by relaxing some of these assumptions is worthwhile. Furthermore, as that in most of the literature, we take cross-holdings as exogenously given to study how an increase in cross-holdings affects consumer surplus. A possible future direction is to endogenize the decision to acquire shares in our model, which can be assumed either before or after the stage of the welfare-maximizing tax policy.Footnote 22 We believe this will generate rich policy implications and greatly enrich the current literature.

Change history

20 May 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00712-024-00866-x

Notes

In 2006, the British Sky Broadcasting Group (BSkyB) acquired 17.9% of ITV. The UK Competition Commission ordered the partial investment down to a level below 7.5%. Comparably, in 2013, the Competition Commission investigated Ryanair’s acquisition in Aer Lingus and ordered Ryanair to reduce its shareholding to 5%.

So far, some countries in Europe such as Austria, Germany and the United Kingdom are competent to review passive cross holdings. The list outside Europe includes the United States, Japan, and Brazil.

There have also been studies on the collusive effects of cross-holdings in repeated settings. Malueg (1992) shows that cross-holdings have an ambiguous effect on collusion in a repeated Cournot duopoly. Gilo et al. (2006, 2013) find that cross-holdings can facilitate collusion in the infinitely repeated Bertrand model. Yang and Zeng (2021) examine the collusive effect of cross-holding with the introduction of cost asymmetry in an infinitely repeated Cournot duopoly game. The authors show that increasing cross-holding may either facilitate or hinder collusion. However, our analysis focuses on static competition.

We find a few exceptions. Bárcena-Ruiz and Campo (2012) study the effects of cross-holdings in a model with strategic environmental policy, Fanti and Buccella (2016, 2021) revisit the classic issue of the strategic trade policy with the consideration of unilateral and bilateral cross-holdings, respectively.

We discuss bilateral cross-holdings (seen also in Malueg 1992; Bárcena-Ruiz and Campo 2012; Fanti 2016a; López and Vives 2019 etc.) in case 1 and 2, and unilateral cross-holdings (seen also in Farrell and Shapiro 1990; Ghosh and Morita 2017; etc.) in case 3 and 4. Though unilateral cross-holdings are widely observed in reality, we also observe an increasing trend of bilateral cross-holdings. For example, there are bilateral shareholdings between Renault and Nissan, Toyota and Subaru, BAIC Motor and Daimler AG, Air China and Cathay Pacific Airways, Tencent and Spotify, etc. Fanti and Buccella (2021) have thoroughly discussed the reasons that drive bilateral cross-ownership while providing some real-world examples.

Fanti (2016a) shows that the downstream bilateral cross-holdings in a Cournot duopoly may be socially desirable when the (upstream) labor market is unionized. Fanti (2016b) demonstrates that the downstream unilateral cross-holding in a Bertrand competition may be socially desirable when the products are strategic complements and are not too differentiated, as the effect of reduced input price outweighs the collusive effect under such conditions.

Due to the critical difference between passive cross-holdings and mergers, the well-known results of mergers can not be naturally extended to the case of passive cross-holdings.

If we consider a horizontal merger, case 1 refers to the situation in which we have a reduction in the number of efficient firms. And the remaining cases (case 2–4) correspond to the situation in which we have a reduction in the number of inefficient firms. Our model of cross-holdings applies to a general case with partial ownership acquisitions among symmetric firms or asymmetric firms.

For the purpose of a clear presentation, we assume symmetric ownership shares in acquired firms. With the presence of identical firms, it is reasonable to assume symmetric ownership shares between identical firms in each group. The assumption of a symmetric case of ownership can also be observed in the literature such as Malueg (1992) and López and Vives (2019).

In each case, we show that firms may obtain the motivation to jointly increase the degree of cross-holdings. In other words, under certain circumstances, increasing the degree of cross-holdings leads to higher joint profit for involved firms.

We implicitly assume that there are no costs for the government to impose different taxes in different industries (see also in Anderson et al. 2001; Wang and Zhao 2009; Dinda and Mukherjee 2014). Our result does not change if there is a fixed cost for government to impose strategic taxes. Furthermore, if the implementation cost is a fraction of the tax revenue, our analyses should carry through but our result may depend on the magnitude of the implementation cost.

If \(\tau ^*>0\), we must have \(a-c >c (m+n) (1-\delta )\), which leads to \(\tau ^*>1\) by (4). This contradicts with the assumption of \(\tau <1\). Therefore, we have \(\tau ^*<0\).

Notice that we have \(\delta <1-\frac{a-c}{c (m+n)}\) given \(\tau ^*<0\). Thus, \(\delta < min\{\frac{1}{2}, 1-\frac{a-c}{c (m+n)}\}\).

Denote \(N=n+m\). It can be further calculated that \(\frac{\partial \tau ^*}{\partial N }= \frac{c (a-c)(1-\delta )}{(a-c (N(1-\delta ) +1))^2}>0,\) which indicates that the designed subsidy decreases with the number of firms.

As we see from (1), for case 1 and similarly for case 2, our results hold when each engaged firm owns \(1-\delta\) percent of its own shares and a total \(\delta\) percent of shares in target firms.

The condition for \(\partial \pi _i^{1*}/\partial \delta\) to be positive or negative can be obtained through straightforward calculations. However, these conditions are considerably complicated and therefore not informative. We thus omit the expressions of the derivative and the conditions in this and the subsequent cases for the sake of readability and clarity.

The unconventional result, where an increase in cross-ownership can enhance consumer surplus and social welfare within a vertical industry, is observed under price competition but not under Cournot competition.

Note that, under certain circumstances, the government may raise the tax rate to mitigate inefficiencies in product distribution, which can also have a negative impact on industry output.

Consider adding a stage in which firms choose the degree of cross-holdings to maximize their profits before the government optimizes social welfare. Our current numerical analysis indicates that, in Example 1–4, the equilibrium ownership rates are \(37.03\%\), \(33.75\%\), \(36\%\) and \(17.17\%\), respectively. We also have simulations which show that the equilibrium ownership rate can be either zero (i.e., the joint profit of involved firms decreases after engaging in cross-holdings) or 1/2 under other circumstances.

References

Alley WA (1997) Partial ownership arrangements and collusion in the automobile industry. J Ind Econ 45:191–205

Anderson SP, de Palma A, Kreider B (2001) The efficiency of indirect taxes under imperfect competition. J Public Econ 81:231–251

Bárcena-Ruiz JC, Campo ML (2012) Partial cross-ownership and strategic environmental policy. Resour Energy Econ 34:198–210

Brito D, Cabral L, Vasconcelos H (2014) Divesting ownership in a rival. Int J Ind Organ 34:9–24

Dietzenbacher E, Smid B, Volkerink B (2000) Horizontal intergration in the dutch financial sector. Int J Ind Organ 18:1223–1242

Dinda S, Mukherjee A (2014) A note on the adverse efect of competition on consumers. J Public Econ Theory 16:157–163

European Commission (2014) White paper: towards more effective EU merger control. Brussels, 9.7.2014. COM(2014) 449 final

Fanti L (2015) Partial cross-ownership, cost asymmetries, and welfare. Econ Res Int 2015:324507

Fanti L (2016a) Interlocking cross-ownership in a unionised duopoly: when social welfare benefits from ‘more collusion. J Econ 119:47–63

Fanti L (2016b) Social welfare and cross-ownership in a vertical industry: when the mode of competition matters for antitrust policy. Jpn World Econ 37–38:8–16

Fanti L, Buccella D (2016) Passive unilateral cross-ownership and strategic trade policy. Economics 10(1):1–21

Fanti L, Buccella D (2021) Strategic trade policy with interlocking cross-ownership. J Econ 134:147–174

Farrell J, Shapiro C (1990) Asset ownership and market structure in oligopoly. Rand J Econ 21:275–292

Flath D (1992) Horizontal shareholding interlocks. Manag Decis Econ 13(1):75–77

Gassler M (2018) Non-controlling minority shareholdings and EU merger control. World Compet 41(1):3–42

Ghosh A, Morita H (2017) Knowledge transfer and partial equity ownership. Rand J Econ 48(4):1044–1067

Gilo D, Moshe Y, Spiegel Y (2006) Partial cross ownership and tacit collusion. Rand J Econ 37:81–99

Gilo D, Spiegel Y, Temurshoev U (2013) Partial cross ownership and tacit collusion under cost asymmetries. In: Working paper, Tel-Aviv University

Hu Q, Monden A, Mizuno T (2022) Downstream cross-holdings and upstream R &D. J Ind Econ 70(3):775–789

Levy N (2013) EU merger control and non-controlling minority shareholdings: the case against change. Eur Compet J, 721–753

Liu C-C, Mukherjee A, Wang LFS (2015) Horizontal merger under strategic tax policy. Econ Lett 136:184–186

Liu L, Lin J, Qin C (2018) Cross-holdings with asymmetric information and technologies. Econ Lett 166:83–85

López ÁL, Vives X (2019) Overlapping ownership, R &D spillovers, and antitrust policy. J Polit Econ 127(5):2394–2437

Ma H, Zeng C (2022) The effects of optimal cross holding in an asymmetric oligopoly. Bull Econ Res 74(4):1053–1066

Ma H, Qin C, Zeng C (2021) Incentive and welfare implications of cross-holdings in oligopoly. Econ Theory (forthcoming)

Malueg DA (1992) Behavior and partial ownership of rivals. Int J Ind Organ 10:27–34

Nain A, Wang Y (2018) The product market impact of minority stake acquisitions. Manage Sci 64(2):825–844

OECD (2012) The role of efficiency claims in antitrust proceedings. Policy Roundtables, Available at http://www.oecd.org/competition/EfficiencyClaims2012.pdf

Reynolds RJ, Snapp BR (1986) The competitive effects of partial equity interests and joint ventures. Int J Ind Organ 4:141–153

Shelegia S, Spiegel Y (2022) Partial cross ownership and innovation. In: Working paper

Shuai J, Xia M, Zeng C (2023) Upstream market structure and downstream partial ownership. J Econ Manag Strategy 32(1):22–47

Trivieri F (2007) Does cross-ownership affect competition?: Evidence from the Italian banking industry. J Int Finan Markets Inst Money 17(1):79–101

Vergé T (2010) Horizontal mergers, structural remedies and consumer welfare in a Cournot oligopoly with assets. J Ind Econ 58(4):723–741

Wang XH, Zhao J (2009) On the efficiency of indirect taxes in differentiated oligopolies with asymmetric costs. J Econ 96:223–239

Yang J, Zeng C (2021) Collusive stability of cross-holding with cost asymmetry. Theor Decis 91(4):549–566

Acknowledgements

We thank the editor, Giacomo Corneo, and an anonymous reviewer for their constructive comments and suggestions that have helped to greatly improve the paper. Financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 72273153) and “the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities”, Zhongnan University of Economics and Law (Grant No. 2722023DK006) are gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: In this article Soumyananda D, Mukherjee A reference has been changed to Dinda S, Mukherjee A.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Proof of Lemma 1

Without cross-holdings, we have

where \(N= m+n\). Both the denominator and numerator are linear in a. Therefore, straightforward calculations yields

where \(T_1= \frac{(m+n+1) \left( c^2\,m+d^2n +mn (c-d)^2\right) }{c m+d n},\) and \(T_2= \frac{c^2\,m +d^2 n + m n (c-d)^2 (m+n+2) }{c m+d n}.\) Notice that we have \(T_1-T_2= cm + dn\).

Further, taking derivative with respect to \(\delta\) over \(\tau ^{1*}\) yields

where \(D_2= c d m (1+ m + 3 n (1-\delta ))- c^2\,m (2+ m + 2 n (1-\delta )) - d^2 n (m+1) (1-\delta ).\) It can be calculated that \(D_2<0\) for any \(c>d>0\), \(m>0\), \(n>0\) and \(0<\delta <1/2\). Therefore, if \(d/c<m/(1+m)\), we must have \(\partial \tau ^{1*}/\partial \delta <0\). If \(d/c>m/(1+m)\), we have \(\partial \tau ^{1*}/\partial \delta <0\) when \(a d (c m +d n (1-\delta ))+(d (m+1)-c m) D_2>0\) and \(\partial \tau ^{1*}/\partial \delta >0\) when \(a d (c m +d n (1-\delta ))+(d (m+1)-c m) D_2<0\).

1.2 Proof of Lemma 2

Without cross-holdings, we have

Both the denominator and numerator are linear in a. Therefore, we can simplify the condition of \(\tau ^{3*}\) being tax or subsidy into intervals in terms of a. Straightforward calculations yields

where \(T_3=\frac{(m+n+1) \left( c^2\,m+ \left( (c-d)^2\,m +d^2\right) n\right) }{c m+d n}\), and \(T_4=\frac{m \left( c^2+ (c-d)^2 (m+2) n + (c-d)^2 n^2\right) +d^2 n}{c m+d n}\). The distance between the two cutoffs is \(T_3-T_4= cm+dn\).

More generally, taking derivative with respect to \(\delta\) over \(\tau ^{3*}\) yields

where \(F=a c (c m (1-\delta )+d n)-L\), and

The sign of \(\partial \tau ^{3*}/\partial \delta\) depends solely on the sign of F. We have \(\partial \tau ^{3*}/\partial \delta >0\) if \(F<0\), and vice versa. Taking derivative of F with respect to \(\delta\) yields

When \(a<{(d+(c-d) m) (c+(c-d) n)}/{c}\), \(\partial F/\partial \delta >0\), which indicates F increases with \(\delta\) in (0, 1/2). We find that \(F|_{\delta =0}<0\) and \(F|_{\delta =1/2}<0\). Hence, \(F<0\) for any \(\delta \in (0, 1/2)\), which implies \(\partial \tau ^{3*}/\partial \delta >0\) in this case. When \(a>{(d+(c-d) m) (c+(c-d) n)}/{c}\), \(\partial F/\partial \delta <0\), which indicates F decreases with \(\delta\) in (0, 1/2). We find that

where \(G=\frac{c+(c-d) n}{c (c m+d n)}\left( c^2 m (m+2 n+2)-c d m (m+3 n+1)+d^2 n (m+1) \right)\); and

where \(H=\frac{c+(c-d) n}{c (c m+2 d n)}\left( c^2 m (m+4 n+4)-c d m (m+6 n+3)+2 d^2 n (m+1) \right)\). Since

given that \(\partial F/\partial \delta < 0\), we have the following results:

-

1)

when \({(d+(c-d) m) (c+(c-d) n)}/{c}<a<G\), we have \(F|_{\delta =0}<0\) and \(F|_{\delta =1/2}<0\). Then \(F<0\) for any \(\delta \in (0, 1/2)\). Thus, \(\partial \tau ^{3*}/\partial \delta >0\);

-

2)

when \(G<a<H\), we have \(F|_{\delta =0}>0\) and \(F|_{\delta =1/2}<0\). Then F decreases from a positive number to a negative number as \(\delta\) increases from 0 to 1/2. Thus, \(\partial \tau ^{3*}/\partial \delta\) would correspondingly be negative and then positive.

-

3)

when \(a>H\), we have \(F|_{\delta =0}>0\) and \(F|_{\delta =1/2}>0\). Then \(F>0\) for any \(\delta \in (0, 1/2)\). Thus, \(\partial \tau ^{3*}/\partial \delta <0\).

In conclusion, we have

1.3 The expression for joint profit in Case 3

\(\Pi ^{3*}= n \pi _i^{3*}+m \pi _j^{3*}\), straightforward calculations lead to

1.4 Detailed calculations for the case of unit tax

All settings remain consistent with the basic model, except that we have replaced the ad valorem tax \(\tau\) with a unit tax t. Moreover, this tax may function as a tax when t is positive and as a subsidy when t is negative.

Case 1: Cross-holdings between efficient firms

In the second stage, each firm simultaneously chooses the optimal quantity to achieve profit maximization. The profit for each efficient firm is

while the profit for each inefficient firm is \(\pi _j=(a-Q-t-c) q_j.\) Solving the first-order conditions leads to the equilibrium outputs as

All the second-order conditions in this section are satisfied.

In the first stage, the government chooses the unit tax t to maximize social welfare

By solving the first-order condition, we obtain

Substituting it into the outputs, we get the equilibrium industry output as

Differentiating it with respect to \(\delta\) leads to

Case 2: Cross-holdings between inefficient firms

By analogy, we can easily obtain the equilibrium outcomes when inefficient firms hold passive ownership in each other. A simple way to do this is to switch n and m with each other, and switch d and c with each other in case 1. Thus, we obtain

Simple calculations lead to

Case 3: Efficient firms hold shares in inefficient firms

The profit for each efficient acquiring firm is

while that for each inefficient acquired firm is \(\pi _j=(1-\delta )(a-Q-t-c) q_j.\) Standard calculations by solving the first-order conditions yields

In the first stage, the government chooses a optimal unit tax t to maximize social welfare, which yields

The equilibrium industry output is

Differentiating \(Q^{3*}\) with respect to \(\delta\) leads to

Case 4: Inefficient firms hold shares in efficient firms

We can easily obtain the equilibrium outcomes in case 4 by switching n and m with each other, and switching d and c with each other in case 3. Thus, we obtain

Simple calculations lead to

As in the basic model, numerous examples can be found to substantiate that, under certain circumstances, the firms have the incentive to increase cross-holdings in these four cases.

1.5 Simulations for the case of price competition

We conduct extensive numerical simulations and present the results in Tables 1, 2, 3, and 4. The Mathematica codes to solve each case and generate the tables are available upon request. In each table, we use \(a=100, c=10, d=6\) and \(\gamma =0.5\). We assign different values to m and d and increase \(\theta\) from 0.00 to 0.45. In each case, we consider four values for m, which are listed in the first column, and four values for d, which are given in the second row at the top. The equilibrium industry output is provided in the last four columns. The "/" in the tables implies that these parameter values fail to satisfy the assumptions in our model.

As we see in these tables, an increase in the degree of cross-holdings has adverse effects on \(Q^*\) and thus hurts consumers in cases 1 and 3, while improving \(Q^*\) and thus benefiting consumers in cases 2 and 4.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheng, H., Wu, X. & Zeng, C. Can cross-holdings benefit consumers?. J Econ 141, 245–273 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00712-023-00850-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00712-023-00850-x