Abstract

Introduction

Meningiomas account for over 30% of all primary brain tumors. While surgery can be curative for these tumors, several factors may lead to a higher likelihood of recurrence. For recurrent meningiomas, bevacizumab may be considered as a therapeutic agent, but literature regarding its efficacy is sparse. Thus, we present a systematic review of the literature and case series of patients from our institution with treatment-refractory meningiomas who received bevacizumab.

Methods

Patients at our institution who were diagnosed with recurrent meningioma between January 2000 and September 2020 and received bevacizumab monotherapy were included in this study. Bevacizumab duration and dosages were noted, as well as progression-free survival (PFS) after the first bevacizumab injection. A systematic review of the literature was also performed.

Results

Twenty-three patients at our institution with a median age of 55 years at initial diagnosis qualified for this study. When bevacizumab was administered, 2 patients had WHO grade I meningiomas, 10 patients had WHO grade II meningiomas, and 11 patients had WHO grade III meningiomas. Median PFS after the first bevacizumab injection was 7 months. Progression-free survival rate at 6 months was 57%. Two patients stopped bevacizumab due to hypertension and aphasia. Systematic review of the literature showed limited ability for bevacizumab to control tumor growth.

Conclusion

Bevacizumab is administered to patients with treatment-refractory meningiomas and, though its effectiveness is limited, outperforms other systemic therapies reported in the literature. Further studies are required to identify a successful patient profile for utilization of bevacizumab.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Meningiomas account for over 30% of all primary brain tumors and are the most common primary brain tumor [31]. The vast majority of meningiomas are World Health Organization (WHO) grade I, and complete surgical resection may be curative. However, WHO grade II and grade III tumors typically harbor poorer long-term outcomes with 5-year overall survival between 30 and 60%, high recurrence rates, and an arduous clinical course [16, 24, 40].

While surgery with adjuvant radiation is often the first treatment for WHO grade II and grade III meningiomas, re-operations with additional radiation and chemotherapy are considered upon recurrence. An array of chemotherapeutic and targeted molecular drugs are used for the treatment of treatment-refractory meningiomas; however, the majority of these drugs have proven to be largely ineffective, and some may lead to significant complications [40]. Yet, therapies targeting vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) may prove useful for tumor control as meningiomas are known to express large amounts of VEGF [3, 8]. To prevent VEGF activity, bevacizumab, a monoclonal antibody that binds free VEGF and prevents signal transduction, may be administered. Bevacizumab has shown some success in cranial and non-cranial tumors alike, such as metastatic colorectal cancer, non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer, glioblastoma, metastatic renal cell carcinoma, and treatment-refractory carcinomas of the cervix [11, 25]. In theory, bevacizumab should decrease the tumor’s vascularity and inhibit angiogenesis, a key factor in the growth and spread of tumors.

Given the limited literature regarding the effectiveness of bevacizumab for recurrent meningiomas, we present a series of patients from our institution with treatment-refractory cranial meningiomas who were treated with bevacizumab and a systematic review of the literature.

Methods

Institutional data

Patients at our institution who were diagnosed with a recurrent cranial meningioma between January 2000 and September 2020 and received bevacizumab monotherapy specifically for their meningioma were included in this study. Those with neurofibromatosis (NF) (n = 5) or no documentation of compliance with bevacizumab (n = 5) in the electronic health record were excluded. Additionally, patients who did not have consent for their data to be used or had bevacizumab administered for radiation necrosis alone were excluded. Bevacizumab duration and dosages were noted, as well as progression-free survival (PFS) after the first bevacizumab injection. PFS was measured either until clear radiographic tumor recurrence/regrowth or last follow-up. No particular volume of recurrence/regrowth was required for classification as progression. Patients were placed on either 7.5, 10, or 15 mg/kg of bevacizumab every 2 or 3 weeks for the duration of their treatment. Pertinent information regarding previous treatment for the meningioma, including chemotherapy, surgery, and radiotherapy, were collected. Simpson grade of resection of the operation directly prior to the bevacizumab therapy was also noted. Complications secondary to bevacizumab were recorded. The study was approved by our institutional review board approval (IRB number 15–006838).

Systematic review of the literature

The literature was searched by a medical librarian for the concepts of bevacizumab combined with meningioma. The search strategies were created using a combination of keywords and standardized index terms. Searches were performed on July 2020 in Ovid EBM Reviews, Ovid Embase (1974 +), Ovid Medline (1946 + including epub ahead of print, in-process, and other non-indexed citations), Scopus (1970 +), and Web of Science Core Collection (1975 +). Results were limited to the English language with study subjects being limited to humans. All results were exported to Endnote where obvious duplicates were removed leaving 598 citations. An additional search on PubMed was also conducted. The search strategies are provided in Electronic Supplemantary Material 1. The PRISMA flow chart for systematic review inclusion criteria is provided in Supplementary Fig. 2. Patients with NF and studies solely looking at NF-affected cohorts were excluded. Patients and studies without mention of NF were treated as NF negative cohorts. Variables of interest extracted from each of the cohorts included previous treatments, length and dosage of bevacizumab administration, PFS after bevacizumab induction, and any complications from bevacizumab.

Results

Institutional results

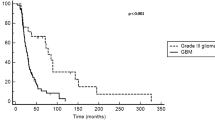

Twenty-three patients from our institution qualified for inclusion in this study. There were 13 men and 10 women with a median age of 55 years at initial meningioma diagnosis. In our cohort, 2 patients had WHO grade I meningiomas, 10 patients had WHO grade II meningiomas, and 11 patients had WHO grade III meningiomas. All patients had surgery and received radiotherapy prior to bevacizumab. The median number of surgeries for these patients was 3 (range 1–10), and the median number of radiotherapies was 3 (range 1–5). In this cohort, 6 patients had a history of chemotherapy prior to bevacizumab. Five patients had one prior chemotheraputic agent, and one had three. Previous chemotherapies included tamoxifen (n = 2), somatostatin analogues (n = 3), everolimus (n = 1), sunitinib (n = 1), and hydroxyurea (n = 1). A swimmer plot detailing each patient’s treatment history prior to bevacizumab initiation can be found in Fig. 1. The median number of doses administered was 10 (1–34 doses), and median duration on bevacizumab monotherapy was 4 months. A total of 3 patients were placed on a dosing regimen of 7.5 mg/kg every 3 weeks, 7 were placed on a schedule of 10 mg/kg every 2 weeks, and 2 patients were placed on 15 mg/kg every 2 weeks. Of the patients on the 15 mg/kg regimen, one shifted the dose and interval to 10 mg/kg every 3 weeks 2 months after beginning bevacizumab due to hypertension secondary to bevacizumab: the other transitioned to 15 mg/kg infusion every 3 weeks. The median PFS after the first bevacizumab injection was 7 months (1–75 months). A Kaplan–Meier curve depicting PFS can be seen in Fig. 2. Progression-free survival rate at 6 months (PFS-6) was 57%. Of the 23 patients included, 18 patients had tumor progerssion after bevacizumab. With the exception of one patient with a WHO grade III meningioma with distant metastasis, all recurence was local. Seventy-seven percent of the patients in this cohort went on to further treatment after bevacizumab failure. Reported complications during bevacizumab monotherapy included hypertension (n = 3), nausea (n = 1), fatigue (n = 1), proteinuria (n = 1), bleeding (n = 1), aphasia (n = 1), anorexia (n = 1), and pulmonary embolism (n = 1). Of these patients, two were taken off bevacizumab due to hypertension and aphasia. These results are displayed in Table 1.

Two patients in our cohort had a WHO grade I meningioma at the time of bevacizumab infusion. Of note, one patient’s most recent biopsy before starting bevacizumab was 12 years prior, and the biopsy 22 months after bevacizumab induction indicated that the meningioma had transformed into a WHO grade II. One of the patients had one surgery and one radiotherapy prior to the first bevacizumab administration, and the other one had two and three, respectively. One patient received 10 mg/kg of bevacizumab every 2 months. The other patient had an infusion of 15 mg/kg every 2 weeks, which was reduced to 10 mg/kg every 3 weeks after his treatment was complicated by hypertension. The average duration of treatment with bevacizumab was 12 months. For these two patients, the median PFS was 11 months (PFS-6 = 50%).

Ten patients had WHO Grade II meningiomas in our cohort. The median age of these patients at initial tumor diagnoses was 55.5 years. All patients had surgery and radiotherapy prior to starting on bevacizumab. The median number of surgeries was 3.5 (range 1–10), and the median number of radiation treatments was 3 (range 1–5). Of the patients whose charts detailed dosage modalities (n = 4), 2 patients received 10 mg/kg of bevacizumab every 2 weeks for a median duration of 16 months (15–17), and 2 patients received 7.5 mg/kg of bevacizumab every 3 weeks for a median of 14.5 months (12–17). Overall, the median time receiving bevacizumab was 7.5 months. Seven patients had progressive disease. The median PFS for this group of patients was 12 months (range 1–45 months, PFS-6 = 56%). One patient stopped treatment after one dose of bevacizumab due to hypertension and rigidity. Subsequent surgery, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy was utilized after failure of bevacizumab in 86% of patients.

Eleven patients had WHO grade III meningiomas. Median age at initial tumor diagnoses was 53 years. All patients had surgery and radiotherapy prior to starting bevacizumab. The median number of surgeries was 3 (range 1–7), and the median number of radiation treatments was 2 (range 1–5). Among patients with recorded data regarding dosage (n = 6), 4 patients received 10 mg/kg of bevacizumab every 2 weeks for a median duration of 4 months (3–7), 1 patient received 7.5 mg/kg of bevacizumab every 3 weeks for 2 months, and one patient received 15 mg/kg of bevacizumab every 3 weeks for 16 months. The median duration on bevacizumab was 4 months (1–21). Overall, this cohort had a median PFS of 7 months (1–75 months) and PFS of 60% at 6-month follow-up. Nine of eleven had recurrence of their meningioma, and 70% of the patients in this cohort went on to further treatment after bevacizumab failure. Of the four patients having complications due to the bevacizumab, one had to discontinue bevacizumab due to anorexia and aphasia. Patient characteristics and progression results stratified by grade can be seen in Table 2.

Though no meaningful analysis could be performed due to the size of the cohort, extent of resection and bevacizumab dosing regimen did not seem to effect disease progression.

Systematic review of the literature

A total of 11 studies containing 101 patients were included in this review [1, 10, 13, 15, 18, 23, 26, 28, 33, 38, 42]. The studies were distributed into 5 case reports, 3 retrospective series, one prospective study, and 2 clinical trials. Of the patients with data regarding recurrences, all patients had at least one recurrence, with one patient having 11 recurrences. Forty-nine patients had at least one previous round of radiotherapy, 30 patients had received at least one cycle of stereotactic radiosurgery, and one patient received proton beam therapy. Twenty-three patients received previous chemotherapy, and at least three patients received three rounds of chemotherapy. Previous chemotherapies included paclitaxel, hydroxyurea, octreotide, sunitinib, pasireotide, tamoxifen, imatinib, etoposide, and temozolomide. Among the patients with bevacizumab dosage data, all received either 5 or 10 mg/kg every 2 or 4 weeks. The results of the systematic review are further outlined in Table 3.

Discussion

In our institution’s cohort, patients who underwent treatment with bevacizumab often had a long clinical course which frequently included multiple sessions and types of radiation therapy, medical therapy, and surgical interventions before bevacizumab was initiated. Yet, the median PFS after bevacizumab was only 7 months after a median treatment time of 4 months. The patients in our cohort with WHO grade I meningiomas had a PFS of 11 months, the median PFS for WHO grade II meningiomas was 12 months, and the median PFS for WHO grade III meningiomas was 7 months.

A systematic review of the literature indicated that patients who received bevacizumab for their recurrent meningiomas had complicated prior histories as well. Many had several rounds of medical therapy, radiatiotherapy, and surgical treatment. Nayak et al. reported one patient who had been living with his WHO grade III meningioma for 12 years and had seven surgeries, radiotherapy, and 11 recurrences or episodes of progression before being placed on bevacizumab, only to present with progression of his tumor after 10 weeks. Their entire cohort had multiple previous surgeries, and seven had prior chemotherapy. Overall, this group had a median of 4 recurrences and had lived with the disease for an average of 10 years. After bevacizumab, the cohort had a median PFS of 6.5 months, and 4 went on to receive further treatment [28].

While bevacizumab, both in our series and in the literature, has not proven to be effective in extending PFS, other medical therapies also seem to have a limited effect on tumor behavior. Among all clinical trials using chemotherapy to target aggressive meningiomas, only four therapies provided results comparable to the results of bevacizumab at our institution and in the literature: a cyclophosphamide-adriamycin-vincristine cocktail, an interferon-alpha-2B drug, tamoxifen, and a hydroxyurea-imatinib cocktail [14, 19, 23, 35]. In a phase 2 trial of trabectadin for recurrent grade 2 and 3 meningioma, the patients who received bevucizumab in the “physician’s choice of treatment” control arm (n = 9 patients) showed a better response in terms of PFS and OS. Although the study was not powered to assess this response, the result warrants further investigation of anti-VEGF drugs in clinical trials [34]. The results of all published trials with alternative medical agents can be seen in Table 4. More robust studies are needed to decide the comparative efficacy of these drugs.

Of note, our study included a heterogeneous cohort in terms of WHO grade. Further, PFS after bevacizumab induction was not significantly different between WHO grades—corroborating results in the literature. One reason for this finding may be due to an increase in VEGF expression not correlating with higher WHO grades. Pistolesi et al. showed that VEGF expression was not correlated with WHO grade through immunohistochemical analyses and reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction of 40 intracranial meningiomas [32]. This may further complicate treatment modalities as no clear indications are given to administer bevacizumab other than the treatment-refractory nature of the tumor.

To better identify which tumors should receive bevacizumab, it may be useful to investigate whether bevacizumab is more effective in meningiomas with increased VEGF expression. Another possible reason for the lack of correlation between WHO grade and PFS is that WHO grade may have a limited ability to predict recurrence and aggressiveness of meningiomas. This may explain the inclusion of two WHO grade I tumors in our study. To stratify the risk of recurrence for meningiomas, several new studies have looked at utilizing a molecularly integrated grading system. The utilization of these new grading schemes has proven to be more predictive of tumor recurrence and has created more homogenous tumor groups in terms of predicted behavior [10, 27, 37]. Further, correlation of VEGF and tumor behavior should be studied, and, if predictive, its inclusion in molecular grading schemes may be considerd. The advent of more targeted and effective therapies may be possible as tumor aggressivness and pathogenesis are classified on a molecular level.

While reclassification into increasingly homogenous groups may result in more targeted research and more effective therapies for patients afflicted with treatment-refractory meningiomas, treatment staging may also affect tumor progression. The outcomes for patients in a study by Furuse et al. showed that radiation—at any point in the treatment timeline—prior to starting bevacizumab had a positive impact in extending PFS when bevacizumab was used. For anaplastic tumors that were previously radiated, 5 tumors stayed stable while 4 reduced in size. For anaplastic tumors not previously radiated, 1 tumor stayed stable while 2 tumors progressed [13]. This study may highlight the importance of treating meningiomas with radiation prior to trying bevacizumab, and not attempting medical treatment before other modalities have been tried. Comparing the two strategies in our study was not possible in our study, as all included patients had a history of radiotherapy. Though no biological explanation can currently be proposed, the sample size of the study is small, and the efficacy of radiotherapy in WHO grade 2 and 3 meningiomas requires further study, this specific treatment sequence may serve to increase the effectiveness of bevacizumab or rule out its use altogether if the tumor responds to radiation.

While bevacizumab does not seem to halt meningioma progression effectively, its relatively low-risk profilein our series and the literature makes it more tolerable than alternative medical therapies. Eight patients in our cohort had complications, of which two stopped treatment. None, however, were debilitating or lifethreatening. In the literature, only a small proportion of patients experienced complications from bevacizumab. Regarding trials of other chemotherapies and targeted molecular therapies, sunitinib had the worst complications including several hemorrhages and gastrointestinal perforations [20].

Limitations

Despite providing the one of the largest cohorts of treatment-refractory meningiomas treated with bevacizumab to date, this study does harbor limitations. Regarding our institutional results, there was heterogenity in site of previous treatments and bevacizumab administration, treatment doses, and tumor classification. Thus, data including dosage, extent of resection prior to receiving bevacizumab, and duration on bevacizumab is missing in several patients. Further, as meningiomas are more acurately being classified based on molecular characteristics, WHO grade, the only classification available for the patients in our cohort, may be a poor predictor of the efficacy of bevacizumab. Our study also utilized Simpson grade to categorize extent of resection, which is largely qualitative and may be inacurate. To address these limitations, a more objective classification, such as the “Copenhagen classification,” could have been used [17]. Regarding the systematic review, outcomes of interest were heterogenous between studies, precluding the possibility of a formal meta-analyses.

Conclusion

Patients with recurrent meningiomas do not seem to benefit significantly from bevacizumab, and tumor response is not correlated with any known patient or tumor characteristics. When compared to other systemic therapies for recurrent meningiomas in the literature, however, bevacizumab may be the most effective, and select patients had long-term tumor control. To better identify and treat treatment-refractory meningiomas, further studies utilizing molecular grading schemes and looking at variations in treatment staging are needed.

References

Boström JP, Seifert M, Greschus S, Schäfer N, Glas M, Lammering G, Herrlinger U (2014) Bevacizumab treatment in malignant meningioma with additional radiation necrosis. An MRI diffusion and perfusion case study. Strahlenther Onkol 190:416–421

Chamberlain MC (1996) Adjuvant combined modality therapy for malignant meningiomas. J Neurosurg 84:733–736

Chamberlain MC, Glantz MJ (2008) Interferon-alpha for recurrent World Health Organization grade 1 intracranial meningiomas. Cancer 113:2146–2151

Chamberlain MC, Glantz MJ, Fadul CE (2007) Recurrent meningioma: salvage therapy with long-acting somatostatin analogue. Neurology 69. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000271382.62776.b7

Chamberlain MC, Johnston SK (2011) Hydroxyurea for recurrent surgery and radiation refractory meningioma: a retrospective case series. J Neurooncol 104:765–771

Chamberlain MC, Tsao-Wei DD, Groshen S (2004) Temozolomide for treatment-resistant recurrent meningioma. Neurology 62:1210–1212

Chamberlain MC, Tsao-Wei DD, Groshen S (2006) Salvage chemotherapy with CPT-11 for recurrent meningioma. J Neurooncol 78:271–276

Champeaux-Depond C, Weller J (2021) Tamoxifen. A treatment for meningioma? Cancer Treat Res Commun 27:100343

Diaz RJ, Maggacis N, Zhang S, Cusimano MD (2014) Determinants of quality of life in patients with skull base chordoma. J Neurosurg 120:528–537

Driver J, Hoffman SE, Tavakol S, Woodward E, Maury EA, Bhave V, Greenwald NF, Nassiri F, Aldape K, Zadeh G, Choudhury A, Vasudevan HN, Magill ST, Raleigh DR, Abedalthagafi M, Aizer AA, Alexander BM, Ligon KL, Reardon DA, Wen PY, Al-Mefty O, Ligon AH, Dubuc AM, Beroukhim R, Claus EB, Dunn IF, Santagata S, Bi WL (2021) A molecularly integrated grade for meningioma. Neuro Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/noab213

Franke AJ, Skelton WP IV, Woody LE, Bregy A, Shah AH, Vakharia K, Komotar RJ (2018) Role of bevacizumab for treatment-refractory meningiomas: a systematic analysis and literature review. Surg Neurol Int 9:133

Fuentes S, Chinot O, Dufour H, Paz-Paredes A, Métellus P, Barrie-Attarian M, Grisoli F (2004) Hydroxyurea treatment for unresectable meningioma. Neurochirurgie 50:461–467

Furuse M, Nonoguchi N, Kawabata S, Miyata T, Toho T, Kuroiwa T, Miyatake S-I (2015) Intratumoral and peritumoral post-irradiation changes, but not viable tumor tissue, may respond to bevacizumab in previously irradiated meningiomas. Radiat Oncol 10:156

Goodwin JW, Crowley J, Eyre HJ, Stafford B, Jaeckle KA, Townsend JJ (1993) A phase II evaluation of tamoxifen in unresectable or refractory meningiomas: a Southwest Oncology Group study. J Neurooncol 15:75–77

Grimm SA, Kumthekar P, Chamberlain MC, Schiff D, Wen PY, Iwamoto FM, Reardon DA, Purow B, Raizer JJ (2015) Phase II trial of bevacizumab in patients with surgery and radiation refractory progressive meningioma. J Clin Oncol 33:2055–2055

Hanft S, Canoll P, Bruce JN (2010) A review of malignant meningiomas: diagnosis, characteristics, and treatment. J Neurooncol 99:433–443

Haslund-Vinding J, Skjoth-Rasmussen J, Poulsgaard L, Fugleholm K, Mirian C, Maier AD, Santarius T, Rom Poulsen F, Meling T, Bartek JJ, Förander P, Larsen VA, Kristensen BW, Scheie D, Law I, Ziebell M, Mathiesen T (2022) Proposal of a new grading system for meningioma resection: the Copenhagen Protocol. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 164(1):229–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-021-05025-5

Hawasli AH, Rubin JB, Tran DD, Adkins DR, Waheed S, Hullar TE, Gutmann DH, Evans J, Leonard JR, Zipfel GJ, Chicoine MR (2013) Antiangiogenic agents for nonmalignant brain tumors. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base 74:136–141

Kaba SE, DeMonte F, Bruner JM, Kyritsis AP, Jaeckle KA, Levin V, Yung WK (1997) The treatment of recurrent unresectable and malignant meningiomas with interferon alpha-2B. Neurosurgery 40:271–275

Kaley TJ, Wen P, Schiff D, Ligon K, Haidar S, Karimi S, Lassman AB, Nolan CP, DeAngelis LM, Gavrilovic I, Norden A, Drappatz J, Lee EQ, Purow B, Plotkin SR, Batchelor T, Abrey LE, Omuro A (2015) Phase II trial of sunitinib for recurrent and progressive atypical and anaplastic meningioma. Neuro Oncol 17:116–121

Kim Y-S, Jang W-Y, Lee K-H, Moon K-S, Jung T-Y, Jung S (2020) Bevacizumab-refractory radiation necrosis with pathologic transformation of benign meningioma following adjuvant gamma knife radiosurgery: A rare case report. Medicine 99. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000021637

Lamberts SW, Tanghe HL, Avezaat CJ, Braakman R, Wijngaarde R, Koper JW, de Jong H (1992) Mifepristone (RU 486) treatment of meningiomas. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 55:486–490

Lou E, Sumrall AL, Turner S, Peters KB, Desjardins A, Vredenburgh JJ, McLendon RE, Herndon JE 2nd, McSherry F, Norfleet J, Friedman HS, Reardon DA (2012) Bevacizumab therapy for adults with recurrent/progressive meningioma: a retrospective series. J Neurooncol 109:63–70

Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, Burger PC, Jouvet A, Scheithauer BW, Kleihues P (2007) The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol 114:97–109

Marty M, Pivot X (2008) The potential of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy in metastatic breast cancer: clinical experience with anti-angiogenic agents, focusing on bevacizumab. Eur J Cancer 44:912–920

Mukherjee D, Hu JL, Chu RM (2018) Isolated extracranial intraosseous metastasis of an intracranial meningioma following bevacizumab therapy: case report and review of the literature. Asian J Neurosurg 13:98

Nassiri F, Liu J, Patil V, Mamatjan Y, Wang JZ, Hugh-White R, Macklin AM, Khan S, Singh O, Karimi S, Corona RI, Liu LY, Chen CY, Chakravarthy A, Wei Q, Mehani B, Suppiah S, Gao A, Workewych AM, Tabatabai G, Boutros PC, Bader GD, de Carvalho DD, Kislinger T, Aldape K, Zadeh G (2021) A clinically applicable integrative molecular classification of meningiomas. Nature 597:119–125

Nayak L, Iwamoto FM, Rudnick JD, Norden AD, Lee EQ, Drappatz J, Omuro A, Kaley TJ (2012) Atypical and anaplastic meningiomas treated with bevacizumab. J Neurooncol 109:187–193

Newton HB, Scott SR, Volpi C (2004) Hydroxyurea chemotherapy for meningiomas: enlarged cohort with extended follow-up. Br J Neurosurg 18:495–499

Norden AD, Raizer JJ, Abrey LE, Lamborn KR, Lassman AB, Chang SM, Alfred Yung WK, Gilbert MR, Fine HA, Mehta M, DeAngelis LM, Cloughesy TF, Ian Robins H, Aldape K, Dancey J, Prados MD, Lieberman F, Wen PY (2010) Phase II trials of erlotinib or gefitinib in patients with recurrent meningioma. J Neurooncol 96:211–217

Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Farah P, Ondracek A, Chen Y, Wolinsky Y, Stroup NE, Kruchko C, Barnholtz-Sloan JS (2013) CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2006–2010. Neuro Oncol 15 Suppl 2:ii1-56

Pistolesi S, Boldrini L, Gisfredi S, De Ieso K, Camacci T, Caniglia M, Lupi G, Leocata P, Basolo F, Pingitore R, Parenti G, Fontanini G (2004) Angiogenesis in intracranial meningiomas: immunohistochemical and molecular study. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 30:118–125

Puchner MJA, Hans VH, Harati A, Lohmann F, Glas M, Herrlinger U (2010) Bevacizumab-induced regression of anaplastic meningioma. Ann Oncol 21:2445–2446

Preusser M, Silvani A, Le Rhun E, Soffietti R, Lombardi G, Sepulveda JM, Brandal P, Brazil L, Bonneville-Levard A, Lorgis V, Vauleon E, Bromberg J, Erridge S, Cameron A, Lefranc F, Clement PM, Dumont S, Sanson M, Bronnimann C, Balaná C, Thon N, Lewis J, Mair MJ, Sievers P, Furtner J, Pichler J, Bruna J, Ducray F, Reijneveld JC, Mawrin C, Bendszus M, Marosi C, Golfinopoulos V, Coens C, Gorlia T, Weller M, Sahm F, Wick W (2022) Trabectedin for recurrent WHO grade 2 or 3 meningioma: a randomized phase II study of the EORTC Brain Tumor Group (EORTC-1320-BTG). Neuro Oncol 24(5):755–767

Raizer JJ, Grimm SA, Rademaker A, Chandler JP, Muro K, Helenowski I, Rice L, McCarthy K, Johnston SK, Mrugala MM, Chamberlain M (2014) A phase II trial of PTK787/ZK 222584 in recurrent or progressive radiation and surgery refractory meningiomas. J Neurooncol 117:93–101

Renard V, Leach DR (2007) Perspectives on the development of a therapeutic HER-2 cancer vaccine. Vaccine 25 Suppl 2:B17-23

Sahm F, Schrimpf D, Stichel D, Jones DTW, Hielscher T, Schefzyk S, Okonechnikov K, Koelsche C, Reuss DE, Capper D, Sturm D, Wirsching H-G, Berghoff AS, Baumgarten P, Kratz A, Huang K, Wefers AK, Hovestadt V, Sill M, Ellis HP, Kurian KM, Okuducu AF, Jungk C, Drueschler K, Schick M, Bewerunge-Hudler M, Mawrin C, Seiz-Rosenhagen M, Ketter R, Simon M, Westphal M, Lamszus K, Becker A, Koch A, Schittenhelm J, Rushing EJ, Collins VP, Brehmer S, Chavez L, Platten M, Hänggi D, Unterberg A, Paulus W, Wick W, Pfister SM, Mittelbronn M, Preusser M, Herold-Mende C, Weller M, von Deimling A (2017) DNA methylation-based classification and grading system for meningioma: a multicentre, retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol 18:682–694

Shih KC, Chowdhary S, Rosenblatt P, Weir AB 3rd, Shepard GC, Williams JT, Shastry M, Burris HA 3rd, Hainsworth JD (2016) A phase II trial of bevacizumab and everolimus as treatment for patients with refractory, progressive intracranial meningioma. J Neurooncol 129:281–288

Simó M, Argyriou AA, Macià M, Plans G, Majós C, Vidal N, Gil M, Bruna J (2014) Recurrent high-grade meningioma: a phase II trial with somatostatin analogue therapy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 73:919–923

Wen PY, Quant E, Drappatz J, Beroukhim R, Norden AD (2010) Medical therapies for meningiomas. J Neurooncol 99:365–378

Wen PY, Yung WKA, Lamborn KR, Norden AD, Cloughesy TF, Abrey LE, Fine HA, Chang SM, Robins HI, Fink K, Deangelis LM, Mehta M, Di Tomaso E, Drappatz J, Kesari S, Ligon KL, Aldape K, Jain RK, Stiles CD, Egorin MJ, Prados MD (2009) Phase II study of imatinib mesylate for recurrent meningiomas (North American Brain Tumor Consortium study 01–08). Neuro Oncol 11:853–860

Wilson TJ, Heth JA (2012) Regression of a meningioma during paclitaxel and bevacizumab therapy for breast cancer. J Clin Neurosci 19:468–469

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors including A. Yohan Alexander, Chiduziem Onyedimma, Archis R. Bhandarkar, Yagiz U. Yolcu, Giorgos Michalopoulos, Mohamad bydon, and Michael J. Link contributed to the study conception and design. Data collection and analysis were performed by A. Yohan Alexander, Chiduziem Onyedimma, Archis R. Bhandarkar, Yagiz U. Yolcu, and Giorgos Michalopoulos. The manuscript was written by A. Yohan Alexander and reviewed by all authors. All authors including A. Yohan Alexander, Chiduziem Onyedimma, Archis R. Bhandarkar, Yagiz U. Yolcu, Giorgos Michalopoulos, Mohamad bydon, and Michael J. Link read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This retrospective chart review study involving human participants was in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The Human Investigation Committee (IRB) of the Mayo Clinic approved this study. The study was approved by our institutional review board approval (IRB number 15–006838).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Individual patient data and details are not included in our manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Tumor - Meningioma

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Electronic Supplemantary Material 1

(PDF 422 kb)

Supplementary Figure 2

(PNG 343 kb)

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Alexander, A.Y., Onyedimma, C., Bhandarkar, A.R. et al. The role of bevacizumab for treatment-refractory intracranial meningiomas: a single institution’s experience and a systematic review of the literature. Acta Neurochir 164, 3011–3023 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-022-05348-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-022-05348-x