Abstract

Among pituitary adenomas, which are relatively common brain tumors, elements of ectopic, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) secretion, and intratumoral calcification are unusual. Here, we present an extremely rare case of a calcified ectopic TSH-secreting pituitary adenoma arising from the pars tuberalis mimicking craniopharyngioma based on neuroimaging findings. To our knowledge, this is the first case report of calcified ectopic TSH-secreting pituitary adenoma without symptoms of excessive thyroid hormone secretion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pituitary adenomas are the most common lesions found in the sellar region. Among pituitary adenomas, the incidence of calcification in pituitary adenomas is low, ranging from 0.2 to 14.0% in radiological studies [8]. Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH)-secreting pituitary adenomas are also rare, accounting for 0.5%–1% of all pituitary adenomas [5, 14]. Furthermore, there have been only about 100 ectopic pituitary adenomas reported in the literature with occurrence in the suprasellar cistern, sphenoid sinus, sphenoid wing, nasal cavity, petrous temporal bone, and third ventricle [6, 15]. The combination of these three elements (1—calcified-, 2—ectopic-, and 3—TSH-secreting pituitary adenoma) is very rare.

To our knowledge, this is the first case of ectopic TSH-secreting pituitary adenoma with intratumoral calcification radiologically mimicking craniopharyngioma and without symptoms of excessive thyroid hormone secretion reported in the literature.

Case report

History and examination

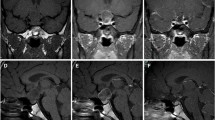

A previously healthy 41-year-old man presented with a 2-year history of worsening visual field defects. Physical examination showed no obvious symptoms of hyperthyroidism, such as sweating, hypertension, palpitations, or weight loss. Laboratory investigations, including tumor biomarkers, revealed no relevant findings. Neuro-ophthalmological examination revealed bitemporal hemianopsia. Computed tomography (CT) indicated a suprasellar round mass with calcification (Fig. 1a, d). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a right-sided peri-infundibular, contrast-enhanced mass that appeared to be separated from the pituitary gland. The mass compressed the right optic nerve and optic chiasm in the upward direction (Fig. 1b, c, e, f). 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18F-FDG) disclosed no hot lesions in the whole body. Taking the findings of a calcified peri-infundibular, contrast-enhanced mass in a middle-aged man into consideration, we suspected the tumor to be a craniopharyngioma. Therefore, endocrinological study was not conducted preoperatively because pituitary adenoma was not included in the differential diagnosis due to the lack of symptoms of excessive pituitary hormones, including hyperthyroidism and radiologically isolated normal pituitary gland.

Preoperative CT scans (a, d) showing a suprasellar iso-density mass with calcification. Preoperative T1-wighted post-contrast coronal (b, c) and sagittal images (e, f) revealing a right-sided suprasellar, contrast-enhanced mass with several non-enhanced calcified components. There is a normal pituitary gland in the sella turcica. No continuity between the tumor and the pituitary tissue is seen (c, e)

Surgery and histopathology

The patient underwent total tumor resection via the right-sided pterional approach. The calcified tumor was soft enough for suction, despite the presence of a granular gritty texture, intraoperatively. The component of the tumor attached to the stalk and optic apparatus was soft, vascular, and yellowish in color. The mass was not related to the anterior pituitary gland, and it was easily dissected from the stalk without injury (Fig. 2).

Intraoperative video-captured photographs. a Before tumor resection: showing the tumor located medial to the right internal carotid artery and inferior to the right optic nerve. b, c During tumor resection: the tumor, which originated from the surface of the stalk, was soft, vascular, and yellowish. d After tumor resection: showing the pituitary stalk and diaphragma sellae remained intact

Histological examination showed diffusely growing adenoma cells with acidophilic or chromophobic cytoplasm (Fig. 3a). Immunohistochemical studies for hormones showed that the tumor was positive for TSH (Fig. 3b) and negative for growth hormone (GH), prolactin, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and luteinizing hormone (LH). Proliferative index by Ki-67 (MIB-1 index) was 1%. Finally, a histopathological diagnosis of calcified ectopic TSH-secreting pituitary adenoma was made.

Postoperative course

The postoperative course was uneventful without complications. The patient was discharged 7 days after surgery with improved visual function. The results of endocrinological study were within the normal ranges, and MRI indicated total removal of the suprasellar tumor with preservation of the pituitary gland and stalk (Fig. 4a, b).

Follow-up

At 7-year follow-up evaluation, the patient’s thyroid function tests were within normal limits, and MRI revealed no tumor recurrence.

Discussion

Ectopic pituitary adenoma is defined as a pituitary adenoma located outside the sella turcica that is not in continuation with the intrasellar normal pituitary gland [3]. The pathogenesis and origin of ectopic pituitary adenomas are generally classified into four types [4]: (1) adenomas derived from residual cells of Rathke’s pouch, which is believed to become the anterior pituitary gland, persisting along the developmental pathway and located in the sphenoid sinus or nasopharynx; (2) adenomas derived from the cells of the supradiaphragmatic portion of the pars tuberalis located in the suprasellar region; and (3) dissemination of the primary intrasellar adenoma, which is not a true ectopic adenoma; and (4) adenomas derived from aberrant migrating cells of the craniopharyngeal duct in the third ventricle. The present case originated from the pars tuberalis completely separated from the normal anterior lobe of the pituitary gland in the sella turcica, as observed by pre- and postoperative MRI and confirmed during surgery, suggesting type 2 ectopic pituitary adenoma. Although these hypotheses have been proposed, the underlying mechanisms have not been elucidated [13].

The suprasellar cistern and sphenoid sinus are the most common location of ectopic pituitary adenoma (both 34.9%), followed by the cavernous sinus (9.3%) and the clivus (8.1%). Almost all of these tumors are midline lesions [6, 7, 11]. On the other hand, suprasellar tumors are generally similar to craniopharyngioma, germ cell tumor, or Rathke’s cleft cyst, and diagnosis of pituitary adenoma is difficult without histopathological evaluation. Although rare, the possibility of ectopic pituitary adenoma should be considered in cases with parasellar lesions.

Ectopic pituitary adenomas also vary in hormonal activities. ACTH-secreting adenomas are reported most frequently (37.2%), followed by prolactinomas (25.6%), endocrine inactive tumors (23.3%), and GH-secreting adenomas (10.5%). Ectopic TSH-secreting adenomas account for only 2.3% of reported ectopic adenomas [6], and only eight such cases have been reported to date. Their clinical features are summarized in Table 1 [1, 2, 7, 9, 10, 12, 13, 15].

Although it has been reported that ectopic pituitary adenomas are mostly found in the sphenoid sinus or bone [7], six of eight cases (75%) with ectopic TSH-secreting pituitary adenomas were located in the nasopharynx (Table 1). This may be a specific characteristic of ectopic TSH-secreting pituitary adenoma compared with other ectopic pituitary adenomas. Similar to TSH-secreting pituitary adenoma, the main clinical manifestations of ectopic TSH-secreting pituitary adenomas are the presence of typical signs and symptoms of excessive TSH production, including thyroid goiter, weight loss, palpitations, excessive sweating, and fatigue. However, not all patients show high levels of TSH or hyperthyroidism [7]. The pharyngeal hypophysis released all six normal pituitary hormones (ACTH, TSH, PRL, LH, FSH, and GH) [10]. It has been suggested that the embryonic residues of pituitary cells produce tumor lesions and synthesize pituitary hormones [10]. However, the types of hormones secreted by ectopic TSH-secreting pituitary adenoma were not identical to each other as shown in Table 1.

Ectopic TSH-secreting pituitary adenoma is difficult to distinguish from other pathologies, including primary hyperthyroidism or Graves’ disease and resistance to thyroid hormone syndrome in the initial clinical stages [10, 13]. However, misdiagnosis can lead to delayed/inappropriate treatment that worsens the disease. In fact, all eight cases of ectopic TSH-secreting pituitary adenoma reported to date (including our patient) were initially misdiagnosed (Table 1). In our case, based on the suprasellar location with intratumoral calcification separated from the normal pituitary gland, the neurosurgeon and radiologist made a diagnosis of craniopharyngioma. Furthermore, the absence of hyperthyroidism made the diagnosis more difficult.

The first-line surgical therapy for such lesions is ectopic adenomectomy. Previously reported tumors located mainly in the extradural nasopharynx were resected via endoscopic endonasal approach (EEA) (Table 1). The transcranial approach is a candidate when the tumor is located in the intradural suprasellar cistern, as in the present case. In some previous cases, the thyroid was targeted because of continued misdiagnosis. The possibility of ectopic TSH-secreting pituitary adenoma should be considered to avoid misdiagnosis and poor outcome. Adenomectomy should be also performed via the most suitable approach based on the surgeon’s preference.

In fact, preoperative hormonal examination was not conducted in the present case because ectopic pituitary adenoma was not included in the differential diagnosis. However, immunoreactivity for pituitary hormones has a distinct diagnostic value. In addition to histopathological confirmation, diagnostic criteria also include radiological evidence of normal pituitary gland [15]. Hence, the diagnosis of our case would be reasonable with ectopic TSH-secreting pituitary adenoma. Ultimately, histological diagnosis is important to make a correct diagnosis.

Conclusion

We presented the first case of calcified ectopic TSH-secreting pituitary adenoma in the suprasellar cistern, which caused bitemporal hemianopsia. Although extremely rare, this pathology should be taken into consideration in cases with parasellar lesions even if obvious hyperthyroidism is not apparent, to further reduce the possibility of future pitfalls and inadequate treatment.

References

Collie RB, Collie MJ (2005) Extracranial thyroid-stimulating hormone-secreting ectopic pituitary adenoma of the nasopharynx. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 133:453–454

Cooper DS, Wenig BM (1996) Hyperthyroidism caused by an ectopic TSH-secreting pituitary tumor. Thyroid 6:337–343

Jung S, Kim JH, Kim TS, Lee MC, Seo JJ, Park JW, Kang SS (2000) Supradiaphragmatic ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone-secreting adenoma. Pathol Int 50:901–904

Kohno M, Sasaki T, Narita Y, Teramoto A, Takakura K (1994) Suprasellar ectopic pituitary adenoma-case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 34:538–542

Mindermann T, Wilson CB (1993) Thyrotropin-producing pituitary adenomas. J Neurosurg 79:521–527

Mitsuya K, Nakasu Y, Nioka H, Nakasu S (2004) Ectopic growth hormone-releasing adenoma in the cavenous sinus-case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 44:380–385

Nishiike S, Tatsumi KI, Shikina T, Masumura C, Inohara H (2014) Thyroid-stimulating hormone-secreting ectopic pituitary adenoma of the nasopharynx. Auris Nasus Larynx 41(6):586–588

Ogiwara T, Nagm A, Yamamoto Y, Hasegawa T, Nishikawa A, Hongo K (2017) Clinical characteristics of pituitary adenomas with radiological calcification. Acta Neurochir 159(11):2187–2192

Pasquini E, Faustini-Fustini M, Sciarretta V, Saggese D, Roncaroli F, Serra D, Frank G (2003) Ectopic TSH-secreting pituitary adenoma of the vomerosphenoidal junction. Eur J Endocrinol 148:253–257

Song M, Wang H, Song L, Tian H, Ge Q, Li J, Zhu Y, Li J, Zhao R, Ji HL (2014) Ectopic TSH-secreting pituitary tumor: a case report and review of prior cases. BMC Cancer 28(14):544

Tamaki N, Shirakuni T, Kokunai T, Matsumoto S, Fujimori T, Maeda S (1991) Ectopic pituitary adenoma in the suprasellar cistern: case report. Surg Neurol 35:389–394

Tong A, Xia W, Qi F, Jin Z, Yang D, Zhang Z, Li F, Xing X, Lian X (2013) Hyperthyroidism caused by an ectopic thyrotropin-secreting tumor of the nasopharynx: a case report and review of the literature. Thyroid 23(9):1172–1177

Wang Q, Lu XJ, Sun J, Wang J, Huang CY, Wu ZF (2016) Ectopic suprasellar thyrotropin-secreting pituitary adenoma: case report and literature review. World Neurosurg 95(617):e13–e18

Wilson CB (1984) A decade of pituitary microsurgery. J Neurosurg 61:814–833

Yang J, Liu S, Yang Z, Shi YB (2017) Ectopic thyrotropin secreting pituitary adenoma concomitant with papillary thyroid carcinoma: case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 96(50):e8912

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures in studies involving human participants were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

The patient has consented to the submission of this case report for submission to the journal.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Pituitaries

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hanaoka, Y., Ogiwara, T., Kakizawa, Y. et al. Calcified ectopic TSH-secreting pituitary adenoma mimicking craniopharyngioma: a rare case report and literature review. Acta Neurochir 160, 2001–2005 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-018-3638-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-018-3638-1