Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the factors predictive of anastomotic leakage in patients undergoing elective right-sided colectomy.

Methods

The subjects of this retrospective study were 247 patients who underwent elective right hemicolectomy or ileocecal resection with ileocolic anastomosis between April 2012 and March 2019, at our institution.

Results

Anastomotic leakage occurred in 9 of the 247 patients (3.6%) and was diagnosed on median postoperative day (POD) 7 (range POD 3–12). There were no significant differences in the background factors or preoperative laboratory data between the patients with anastomotic leakage (anastomotic leakage group) and those without anastomotic leakage (no anastomotic leakage group). Open surgery was significantly more common than laparoscopic surgery (P = 0.027), and end-to-side anastomosis was less common (P = 0.025) in the anastomotic leakage group. The C-reactive protein (CRP) level in the anastomotic leakage group was higher than that in the no anastomotic leakage group on PODs 3 (P < 0.001) and 5 (P < 0.001). ROC curve analysis revealed that anastomotic leakage was significantly more frequent in patients with a serum CRP level ≥ 11.8 mg/dL [area under the curve (AUC) 0.83].

Conclusion

A serum CRP level ≥ 11.8 mg/dL on POD 3 was predictive of anastomotic leakage being detected on median POD 7.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Anastomotic leakage is associated with mortality, short- and long-term morbidity, a potentially increased risk of recurrence, and poor prognosis [1, 2]. The anastomotic leakage rate after right-sided colectomy is reported to range from 1.7 to 12% [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13].

There is limited information on the predictors of anastomotic leakage after ileocolic anastomosis. Several factors, including the host genetic profile, gut microbiome, inflammation, and other immune responses, have been reported to influence the occurrence of anastomotic leakage [1]. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after right-sided colectomy include age, male sex, body mass index (BMI), diabetes, weight loss > 10%, American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status (ASA-PS), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), smoking, arterial hypertension, ascites, peripheral vein disease, low protein or albumin (Alb) level, low sodium level, high CRP level, emergency surgery, long operation time, perioperative transfusion, stapled anastomosis, and delayed bowel motility [4, 7,8,9,10,11,12]. The ability to predict the risks of anastomotic leakage, preoperatively or immediately after surgery, would benefit patients scheduled to undergo elective right-sided colectomy.

The aim of this retrospective study was to investigate the pre-, intra-, and post-operative predictive factors for anastomotic leakage in patients undergoing elective right-sided colectomy.

Patients and methods

Patients

This retrospective single-center study was approved by our organization’s institutional review board, with written informed consent waived (approval number: 866). A total of 247 patients who underwent elective right hemicolectomy or ileocecal resection with ileocolic anastomosis between April 2012 and March 2019 at our institution were enrolled.

Ileocolic anastomoses were constructed in a handsewn, stapled functional end-to-end, or stapled end-to-side manner [14], and all procedures were extracorporeal. The method of anastomosis was decided by the surgeon. As perioperative prophylactic intravenous antibiotics, cefmetazole was administered on the day of the operation and then on a postoperative day (POD) 1. Perioperative peroral antibiotics were not given.

Diagnosis of anastomotic leakage

Anastomotic leakage was diagnosed based on the symptoms of fever, abscess, or septicemia associated with the escape of luminal contents from the site of anastomosis into a drain or an adjacent local area, detected on imaging [15].

Study design and outcome

We compared the background status, preoperative laboratory data, surgical procedure, and postoperative data in the patients with anastomotic leakage (anastomotic leakage group) and those without anastomotic leakage (no anastomotic leakage group). The controlling nutritional status (CONUT) score was calculated using the serum Alb level, total cholesterol level, and total lymphocyte count data [16].

Statistical analysis

Continuous values are expressed as means ± standard deviation and were compared using Student’s t test. Preoperative CA19-9 levels are expressed as medians and were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical values were compared using the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact probability test. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was done to investigate the factors predictive of anastomotic leakage. Differences with a P value < 0.05 were considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP software version 10 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

The perioperative mortality rate was 0.4% (1/247). The median postoperative hospital stay was 8 days (range 5–95 days). Postoperative complications of Clavien-Dindo grade III or higher developed in 14 of the 247 patients (5.7%). Anastomotic leakage was detected in 9 patients (3.6%) and diagnosed on median POD 7 (range PODs 3–12). Treatments for anastomotic leakage included fasting and antibiotics (n = 3), percutaneous drainage (n = 1), and ileostomy (n = 5). Ischemic change was considered one of the causes of leakage in two of the five patients surgically treated for anastomotic leakage and an obvious leakage point was not found in three patients. All nine patients with anastomotic leakage recovered uneventfully and were discharged (Table 1).

Background factors

There were no significant differences between the anastomotic leakage and no aanastomotic leakage groups in age (P = 0.26), sex (P = 0.63), BMI (P = 0.33), smoking history (P = 0.20), COPD (P = 0.22), diabetes mellitus (P = 0.39), hypertension (P = 0.27), CONUT score (P = 0.58), or ASA-PS (P = 0.45). The reasons for elective right-sided colectomy included benign disease (n = 1), cancer (n = 8), and lymphoma (n = 0) in the anastomotic leakage group, and benign disease (n = 25), cancer (n = 207), and lymphoma (n = 6) in the no anastomotic leakage group (P = 0.89) (Table 2).

Preoperative laboratory data

Preoperative laboratory data revealed no significant differences between the groups in white blood cell (WBC) count (P = 0.45), hemoglobin concentration (P = 0.56), serum Alb level (P = 0.75), serum creatinine level (P = 0.42), serum sodium level (P = 0.09), C-reactive protein (CRP) level (P = 0.39), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) level (P = 0.64), or carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) level (P = 0.69) (Table 3).

Surgical factors

Right hemicolectomy was performed more frequently than ileocecal resection in the anastomotic leakage group than in the no anastomotic leakage group (P = 0.051). Surgery was performed via an open approach significantly more often than via a laparoscopic approach in the anastomotic leakage group than in the no anastomotic leakage group (P = 0.027). The cancer stage and CONUT score were both significantly higher (P < 0.001) in the patients who underwent open surgery than in those who underwent laparoscopic surgery. End-to-side anastomosis was significantly less common in the anastomotic leakage group than in the no anastomotic leakage group (P = 0.025). There were no significant differences between the groups in epidural anesthesia (P = 0.39), lymph node dissection (P = 0.65), operation time (P = 0.88), or estimated blood loss (P = 0.98) (Table 4).

Postoperative laboratory data

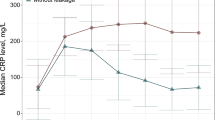

The CRP level was higher in the anastomotic leakage group than in the no anastomotic leakage group on PODs 3 (P < 0.001) and 5 (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1). ROC curve analysis revealed that anastomotic leakage was significantly more common in patients with a serum CRP ≥ 11.8 mg/dL, with an area under the curve (AUC) value of 0.83 (Fig. 2). There were no significant differences in the WBC counts on PODs 1 and 3 between the groups (P = 0.76 and P = 0.35, respectively). However, the WBC count on POD 5 was higher in the anastomotic leakage group than in the no anastomotic leakage group (P = 0.002) (Fig. 3). Likewise, there were no significant differences in the Alb level on PODs 1 and 3 between the groups (P = 0.47 and P = 0.22, respectively), but the Alb level on POD 5 was lower in the anastomotic leakage group than in the no anastomotic leakage group (P = 0.01) (Fig. 4).

No significant differences were observed in the WBC count on postoperative days 1 (P = 0.76) or 3 (P = 0.35) between the patients with and those without anastomotic leakage. The WBC count of the patients with anastomotic leakage was only significantly higher than that in those without anastomotic leakage on postoperative day 5 (P = 0.002)

No significant differences were observed in the albumin level on postoperative days 1 (P = 0.47) or 3 (P = 0.22) between the patients with and those without anastomotic leakage. The albumin level in the patients with anastomotic leakage was only significantly lower than that in those without anastomotic leakage on postoperative day 5 (P = 0.01)

Discussion

We conducted this study to investigate the pre-, intra-, and post-operative predictors of anastomotic leakage following elective right-sided colectomy to enable the selection of optimal treatment strategies for patients with leakage risk factors.

Rausa et al. conducted a meta-analysis of right hemicolectomy comparing open, laparoscopic-assisted, total laparoscopic, and robotic approaches [17]. They found that the anastomotic leakage rate was higher among patients who underwent laparoscopic-assisted and open approaches than among those who underwent total laparoscopic or robotic approaches [17]. Similarly, in the current study, the rate of anastomotic leakage was significantly higher after open surgery than after laparoscopic surgery. As this was a retrospective study, an open approach had been selected for advanced cancer patients with poor nutrition, which might also have affected the leakage rate.

In the current study, the frequency of anastomotic leakage was higher in patients who underwent stapled end-to-end anastomosis than in those with handsewn or stapled side-to-end anastomosis. One previous report found that stapled anastomosis was associated with a significantly lower frequency of anastomotic leakage than handsewn anastomoses [18]; however, several recent reports on ileocolic anastomosis have identified a higher anastomotic leakage rate for stapled vs handsewn anastomoses [5, 6, 10, 11, 13]. Lee et al. compared side-to-side and end-to-side anastomosis approaches in laparoscopic right hemicolectomy [14]. Although anastomotic leakage was not observed in either group, the overall complication rate was lower in the end-to-side group [14].

Previous studies have found that an elevated CRP level after colorectal surgery can be a predictor for anastomotic leakage [19,20,21]. The WBC count peaks 24–48 h after elective surgery, but the CRP level peaks later, at 24–72 h [22]. Watt et al. reported that WBC count was not associated with the magnitude of operative category or invasiveness of the procedure, whereas the CRP level was associated with the magnitude of inflammation, including that caused by anastomotic leakage [22]. Thus, postoperative CRP elevation, but not WBC count elevation, is a predictor of anastomotic leakage following elective right-sided colectomy. A high serum CRP level on POD 3 could be related to an inadequate anastomosis at the time of the operation; however, diagnosis on the day of leakage is too late [23] if all anastomotic leakages are related to the surgical procedure and a weakness has been present since the time of surgery. In the current study, even the obvious leakage point was not recognized in three of five surgically treated patients with anastomotic leakage. It is difficult to establish all the causes of anastomotic leakage after colorectal surgery.

The present study has several limitations. First, it was a retrospective study with a small number of patients at a single institution. The number of patients with anastomotic leakage was also too small to verify the risk factors for leakage. Second, several different surgeons performed the surgical procedures and selected the method of anastomosis according to their preference.

In conclusion, anastomotic leakage occurred in 3.6% of the patients who underwent elective right hemicolectomy or ileocecal resection and was diagnosed on median POD 7. The incidence of anastomotic leakage was significantly higher among patients who underwent open surgery and a stapled side-to-side anastomosis than in those who underwent laparoscopic surgery and a stapled end-to-side anastomosis. Anastomotic leakage also tended to occur more frequently after right hemicolectomy than after ileocecal resection. No predictors of anastomotic leakage were identified among the background factors or preoperative laboratory data we analyzed. A serum CRP level ≥ 11.8 mg/dL, but not an elevated WBC count or serum Alb level, on POD 3 was associated with anastomotic leakage, which assists only with the postoperative prediction of anastomotic leakage. However, anastomotic leakages are frequently diagnosed late and often after hospital discharge [23]. If anastomotic leakage could be predicted on POD 3 and diagnosed on median POD 7, this would help us prepare for the imminent change in the patient’s status.

References

Foppa C, Ng SC, Montorsi M, Spinelli A. Anastomotic leak in colorectal cancer patients: new insights and perspectives. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2020;46(6):943–54.

Ha GW, Kim JH, Lee MR. Oncologic impact of anastomotic leakage following colorectal cancer surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24(11):3289–99.

Kobayashi H, Miyata H, Gotoh M, Baba H, Kimura W, Kitagawa Y, et al. Risk model for right hemicolectomy based on 19,070 Japanese patients in the national clinical database. J Gastroenterol. 2014;49(6):1047–55.

Yoshida T, Miyata H, Konno H, Kumamaru H, Tangoku A, Furukita Y, et al. Risk assessment of morbidities after right hemicolectomy based on the national clinical database in Japan. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 2018;2(3):220–30.

Gustafsson P, Jestin P, Gunnarsson U, Lindforss U. Higher frequency of anastomotic leakage with stapled compared to hand-sewn ileocolic anastomosis in a large population-based study. World J Surg. 2015;39(7):1834–9.

Nordholm-Carstensen A, Schnack Rasmussen M, Krarup PM. Increased leak rates following stapled versus handsewn ileocolic anastomosis in patients with right-sided colon cancer: a Nationwide Cohort Study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2019;62(5):542–8.

Jurowich C, Lichthardt S, Matthes N, Kastner C, Haubitz I, Prock A, et al. Effects of anastomotic technique on early postoperative outcome in open right-sided hemicolectomy. BJS Open. 2019;3(2):203–9.

Elod EE, Cozlea A, Neagoe RM, Sala D, Darie R, Sardi K, et al. Safety of anastomoses in right hemicolectomy for colon cancer. Chirurgia (Bucur). 2019;114(2):191–9.

Kwak HD, Kim SH, Kang DW, Baek SJ, Kwak JM, Kim J. Risk factors and oncologic outcomes of anastomosis leakage after laparoscopic right colectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2017;27(6):440–4.

Jessen M, Nerstrom M, Wilbek TE, Roepstorff S, Rasmussen MS, Krarup PM. Risk factors for clinical anastomotic leakage after right hemicolectomy. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2016;31(9):1619–24.

Frasson M, Granero-Castro P, Rodriguez JLR, Flor-Lorente B, Braithwaite M, Martinez EM, et al. Risk factors for anastomotic leak and postoperative morbidity and mortality after elective right colectomy for cancer: results from a prospective, multicentric study of 1102 patients. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2016;31(1):105–14.

Sanchez-Guillen L, Frasson M, Garcia-Granero A, Pellino G, Flor-Lorente B, Alvarez-Sarrado E, et al. Risk factors for leak, complications and mortality after ileocolic anastomosis: comparison of two anastomotic techniques. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2019;101(8):571–8.

Espin E, Vallribera F, Kreisler E, Biondo S. Clinical impact of leakage in patients with handsewn vs stapled anastomosis after right hemicolectomy: a retrospective study. Colorectal Dis. 2020;22(10):1286–92.

Lee KH, Lee SM, Oh HK, Lee SY, Ihn MH, Kim DW, et al. Comparison of anastomotic configuration after laparoscopic right hemicolectomy under enhanced recovery program: side-to-side versus end-to-side anastomosis. Surg Endosc. 2016;30(5):1952–7.

Peel AL, Taylor EW. Proposed definitions for the audit of postoperative infection: a discussion paper. Surgical Infection Study Group. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1991;73(6):385–8.

de Ulibarri JI, Gonzalez-Madrono A, de Villar NG, Gonzalez P, Gonzalez B, Mancha A, et al. CONUT: a tool for controlling nutritional status. First validation in a hospital population. Nutr Hosp. 2005;20(1):38–45.

Rausa E, Kelly ME, Asti E, Aiolfi A, Bonitta G, Bonavina L. Right hemicolectomy: a network meta-analysis comparing open, laparoscopic-assisted, total laparoscopic, and robotic approach. Surg Endosc. 2019;33(4):1020–32.

Choy PY, Bissett IP, Docherty JG, Parry BR, Merrie A, Fitzgerald A. Stapled versus handsewn methods for ileocolic anastomoses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;7(9): CD004320.

Stephensen BD, Reid F, Shaikh S, Carroll R, Smith SR, Pockney P. C-reactive protein trajectory to predict colorectal anastomotic leak: PREDICT Study. Br J Surg. 2020;107(13):1832–7.

Singh PP, Zeng IS, Srinivasa S, Lemanu DP, Connolly AB, Hill AG. Systematic review and meta-analysis of use of serum C-reactive protein levels to predict anastomotic leak after colorectal surgery. Br J Surg. 2014;101(4):339–46.

Yeung DE, Peterknecht E, Hajibandeh S, Torrance AW. C-reactive protein can predict anastomotic leak in colorectal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2021;36(6):1147–62.

Watt DG, Horgan PG, McMillan DC. Routine clinical markers of the magnitude of the systemic inflammatory response after elective operation: a systematic review. Surgery. 2015;157(2):362–80.

Hyman N, Manchester TL, Osler T, Burns B, Cataldo PA. Anastomotic leaks after intestinal anastomosis: it’s later than you think. Ann Surg. 2007;245(2):254–8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

We have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Masuda, T., Takamori, H., Ogawa, K. et al. C-reactive protein level on postoperative day 3 as a predictor of anastomotic leakage after elective right-sided colectomy. Surg Today 52, 337–343 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-021-02351-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-021-02351-0