Abstract

Aims

Inequalities in diabetes prevalence among immigrants from Andean countries remain unknown. Andean populations are one of the largest groups of immigrants in Madrid city. We examined the association between country of birth and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) prevalence in Andean immigrant population relative to Spanish-natives; and whether this association varied by age, sex and length of residence.

Methods

We analyzed 1,258,931 electronic medical records from Spanish native and Andean immigrant adults aged 40–75 years of Madrid city. We used logistic regression and test interaction terms to address our aims.

Results

Andean immigrants showed 1.13 (95% CI 1.10–1.17) greater adjusted odds for T2DM than Spanish natives. This association was positive in Ecuadorians and Bolivians but protective in Peruvians and Colombians. There was heterogeneity of this association according to age and sex. Relative to Spanish natives, odds of T2DM in Andeans of all ages and women were higher but lower in men.

Conclusion

Andean adults showed greater odds of T2DM compared with Spanish native adults in Madrid, with variation observed by age and sex. These findings emphasize the need for studying immigrant populations in a disaggregated manner to implement specific clinical and preventive approaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a public health problem worldwide and an important cause of premature death, disability and large economic burden for the health care systems and the wider global economy [1]. Worldwide, 8.8% of the adult population had DM in 2015 [2], with around 90% of the cases being type 2 diabetes (T2DM). In Europe, the age-adjusted DM prevalence in adults was 6.8% (5.4–9.9%) in the same year [3]. For Spain, data showed a national age–sex-adjusted DM prevalence in adults ≥ 18 years of 13.8% in 2010 [4]; where 31–75 year-old adults showed a prevalence of DM of 8.3% in men and 5.6% in women. In Madrid Community, data showed an estimated prevalence among adults 30–74 years old of 12.3% in men and 6.4% in women in 2015 [5]. T2DM may be affected by social and cultural factors that may explain the greater prevalence in urban settings [6].

Immigration in Europe is an ongoing sociodemographic phenomenon that started in the 1950s and has increased since the 1990s [7], with Spain and Italy showing the highest increases between 2000 and 2015 [8]. Europe is one of the fastest growing destinations for migrants originating from Latin America and the Caribbean (6.4% per year) [8]. According to the 2015 Statistics National Institute of Spain (INE) [9], the immigrant population defined by country of birth comprised more than 12% of the total population of Spain; where for Madrid, this population represented 17.9%. The majority of the immigrant population in Madrid comes from South America (40.1%), a very diverse region, with a subgroup from Andean countries sharing important social, cultural, economic and historical ties [10]. According to the INE, Andean immigrants in Madrid city from Bolivia, Colombia, Peru and Ecuador represent 72.6% of the South Americans.

Despite the immigrant population being younger and healthier than natives, they are at greater risks of mortality and/or morbidity of DM than natives [11]. In the United States (US), Hispanics have the highest DM prevalence relative to other racial/ethnic minority groups [11]. In Europe, a recent review showed greater DM risk in minority groups, although high-quality data for minorities by country of birth are generally not available [12]. Evidence suggests that the higher levels of health status observed in immigrants deteriorate with increasing length of residence in the host country [13, 14]. These studies attribute this increase to the acculturation process or the adoption of the cultural customs, traditions, practices and behaviors of a host country or society [15]. Specifically, acculturation is influenced by social and cultural factors of the society of origin and of the host society, such as national immigration processes, integration policies, attitudes toward immigration and social support [16, 17], which can be different according to subgroups of the population. These aspects are often not accounted for to explain the deterioration of immigrants’ health regardless of their legal status and socioeconomic position [18].

While there are several studies of DM in Spain, only a few included findings for immigrant populations [19,20,21]. A study in Madrid Community on chronic disorders including DM in all Spanish citizens, found that Latin Americans had lower DM prevalence relative to Spanish nationals [21]. Moreover, a multicenter national study in Spain found a lower control of T2DM in all immigrant groups relative to natives [19]. However, these studies aggregate immigrant populations according to large regions (Latin America, Africa, East Europe, etc.) and have not always used the same aggregation (i.e., Latin America, Ibero-America and South America). These limitations could mask true differences between immigrant and native populations. To address these important gaps, this study aims to investigate the association of country of birth (Andeans vs Spanish-born) with the prevalence of T2DM; and whether this association vary with age, sex and length of residence. For this analysis, the Andean immigrant population was examined as a whole and disaggregated by country of birth (Ecuador, Peru, Colombia and Bolivia).

Methods

Design and data source

A population-based study was conducted using the National Health Insurance database of the Community of Madrid (NHDM) and electronic health records of Primary Healthcare Service of Madrid (AP-MADRID). These data contain anonymized clinical information of all the primary health care centers of Madrid and include among other information sociodemographic characteristics and health conditions coded according to the International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC). Data from AP-MADRID have demonstrated validity for the conduct of health services research and epidemiological studies [22,23,24,25], including the testing of the validity and reliability of DM and hypertension diagnosis codes [22, 23]. The current study is part of the Heart Healthy Hoods Project (hhhproject.eu), a European Research Council funded project aiming to examine the association of social and physical features of the urban environment with cardiovascular health among adults aged 40–75 years in Madrid city [26].

Study population

The Spanish National Health System provides health coverage to 95% of the population in Spain. The primary care is the main entrance to the national health system and is the level of care where most of the care contacts take place. The population coverage for adults aged 40–75 years is around 91% [27]. The study population was selected according to the HHH Project [26] using the following inclusion criteria: (a) individuals registered at one of the 128 primary health care centers of Madrid city; (b) who have the place of residence in the Municipality of Madrid; (c) adults aged 40–75 years; (d) active registers on June 30, 2015; and (e) in case of DM diagnosis: those with T2DM. From the total provided database (n = 1,434,402), we only included those records with country of birth information, Spain or Andean countries (Ecuador, Bolivia, Peru or Colombia), resulting in an analytical sample of 1,258,931 records.

Study variables

Dependent variable

The dependent variable was T2DM diagnosis (yes/no), defined by the Primary Health Service of Madrid through the T90 ICPC code and the methods used for periodic exploitations of indicators monitoring the service portfolio of Primary Healthcare Service of Madrid.

Independent variable

The independent variable was country of birth, specified as the self-report of being born in Spain or in selected Andean countries, as is defined in the NHDM, regardless of citizenship status. Andeans were defined as an aggregate (all Andeans) and disaggregated by country of birth (Ecuador, Colombia, Peru and Bolivia). Hereafter, we refer to those born in Spain as natives.

Covariates

Covariates considered during the analyses were sociodemographic (sex, age and length of residence) and clinical (dyslipidemia and hypertension) variables. Age was calculated as the difference between the data extraction date and the participant’s birth date. For analytical purposes, age was used as categorical according to population tertiles distribution (40–49, 50–60 and 61–75) for the descriptive analysis; and as continuous for the regression analyses. For the immigrant population, length of residence was determined using as proxy the time from immigrant’s registration to the NHDM until the data extraction date. Length of residence was categorized into four groups (0–6, 7–10, 11–13 and 14-more) based on its distribution in the population. Because evidence suggests that recent immigrants have better health outcomes than immigrants with longer stay in the host countries [13, 28], we considered two categories for the lower tertile (0–6 and 7–10). Moreover, for analytic purposes, a variable combining country of birth and length of residence was created and coded as those from Andean countries with 6 or fewer years of residence; Andean with 7–10 years of residence; Andean with 11–13 years of residence; Andean with 14 or more years of residence; and finally, Spanish-born. Dyslipidemia and uncomplicated hypertension have been considered as risk factors for diabetes [29]. These conditions were specified as the presence/absence of these conditions (yes/no), based on physician diagnoses using T93 and K86 ICPC codes, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted for individual characteristics for all Andeans and according to country of birth compared to the Spanish-born population. Differences were determined using the t test for continuous variables with a normal distribution and Chi-square statistic for categorical variables.

We used logistic regression to quantify the association between country of birth and T2DM. Foreign-born was examined first as an aggregate (Andeans) and then according to country of birth (Bolivia, Ecuador, Peru and Colombia). We fitted the following models: (1) unadjusted model; (2) adjusted for sex and age; and (3) finally, additionally adjusted for dyslipidemia and hypertension. Interactions of country of birth with sex, age and length of residence were examined in the fully adjusted model.

A 0.05 significance level was used to assess statistical significance for all comparisons and associations. All data management and statistical analyses were conducted with Stata software version 14.0, StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA.

Results

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the study population by country of birth. Andeans were younger (49.6 vs 55.6 years) and more likely to be women (57.1 vs 53%) than natives. Among Andeans, the largest proportion was from 40 to 49 years old. Bolivians were the youngest (mean age 48.2 vs 55.6 years) and had a higher proportion of women (64.5 vs 53%) relative to natives. Natives had higher prevalence of hypertension (21.7%) and dyslipidemia (28.2%) than Andeans. Among Andeans, Colombians had the highest prevalence of hypertension (11.3) and Peruvians, the highest one of dyslipidemia (24.4%). Overall, most Andeans had resided in Madrid for at least 11 years, except for Bolivians who had resided 7–10 years. This distribution varied according to country of birth, mainly in Bolivians and Ecuadorians. In the Online Resource TS1, we present detailed distribution for the study population by length of residence.

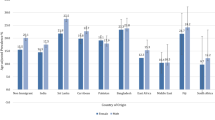

Table 2 shows the distribution of the unadjusted T2DM prevalence. Natives had almost twice the prevalence of Andeans (7.9 vs 4.6%). Compared to Spanish-born, Ecuadorians had the highest prevalence among Andeans. Among Ecuadorians, women had higher T2DM prevalence than men, among Bolivians, women had similar prevalence than men. However, in natives and other Andeans, the prevalence was higher in men than in women. The T2DM prevalence was higher in the Andeans who had resided longer in Spain; a similar pattern was observed by country of birth except in Ecuadorians. In the Online Resource TS2, we present standardized prevalence using the Spanish population of 01/01/2015 as reference.

Table 3 shows the results for the associations between country of birth and T2DM prevalence. In the unadjusted analyses, Andeans had lower odds of T2DM (OR 0.56 95% CI 0.55–0.58); the lower odds was also observed regardless of country of birth. However, after adjusting for age and sex (Model 1), Andeans had higher odds of T2DM than natives (OR 1.05 95% CI 1.02–1.08), with Ecuadorians (OR 1.25 95% CI 1.20–1.30) and Bolivians (OR 1.11 95% CI 1.01–1.22) exhibiting the highest odds. Finally, the fully adjusted model (Model 2) showed that the probability of T2DM in Andeans was 13% (95% CI 1.10–1.17) greater than the natives. As with Model 1, Bolivians and Ecuadorians had greater odds, whereas Peruvians had lower odds relative to natives.

Heterogeneity of the association between country of birth and T2DM was observed for age groups (p < 0.01) and sex (p interaction < 0.01). Andeans had higher odds of T2DM than natives in all the age groups. With the highest odds for Andeans aged 50–60 years (OR 1.20 95% CI 1.15–1.26; Table 4). Andean women had a 31% higher likelihood of T2DM than native women whereas Andean men had 6% lower odds than native men (Table 4). According to the country of birth, these results were significant only for Bolivian and Ecuadorian women, who had greater odds of T2DM than native women; and for Colombian and Peruvian men, who had lower odds than native men.

Andeans who had resided 11 years or more in the city had at least 19% greater odds of T2DM than natives (Online Resource TS3). Despite the lack of heterogeneity by length of residence (p = 0.052), we included the associations for country of birth in Online Resource TS3. Among Bolivians, a pattern of higher probability of T2DM is observed as length of residence increased. Compared with natives, Ecuadorians had greater odds regardless of length of residence, whereas Colombians and Peruvians with 10 years or less of length of residence showed lower or equal odds of T2DM.

Discussion

In this population-based study, Andean immigrants showed a greater odds of T2DM compared to natives, with Ecuadorians and Bolivians having greater odds than natives. Heterogeneity of this association was observed according to age and sex; when compared with natives, Andeans aged 50–60 years old and women had higher odds of T2DM, whereas Andean men showed lower odds of T2DM. Moreover and although not statistical heterogeneity was observed, the odds of T2DM seemed to increase with length of residence among Andeans relative to natives. This pattern was also observed across country of birth.

To the best of our knowledge, there are no previous studies focusing on Andean populations in Spain or Europe. Associations of region of origin with DM have been studied in the USA [13, 30, 31]. South Americans had 40% lower probability of DM than Mexicans [30]. Another US study showed that compared with European men and women, South American men had 12% higher odds of DM, whereas South American women had 12% lower odds [31].

Interestingly, these four Andean countries have lower prevalence of T2DM than Spain according to the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) and the WHO [2, 32]. It is worth noting that the population who migrates and the one staying in their home countries have different characteristics. For example, immigrant populations are mostly young populations [9], as shown in our results. In addition, not all immigrants come from the poorest countries or from the lowest socioeconomic strata. For instance, most of Peruvian immigrants belong to the two highest income quintiles per capita while the majority of those from Ecuador and Bolivia come from the two lowest quintiles [33]. Moreover, the settlement of the Andean population in Spain is mostly in Madrid, Ecuadorians and Bolivians tend to experience higher social isolation than Peruvians and Colombians [34]. Our findings of higher odds among Andeans, as a group or by country of birth relative to natives underscore the need to study this population given the variation of these population characteristics.

Andeans show a higher probability of T2DM than natives regardless of age group. While there are no studies showing results by age groups in immigrant populations, this finding may be important given that the Andean population is younger than the native one. In fact, a study conducted in Canada showed that some immigrant groups, such as Asians and Blacks, developed DM earlier compared with natives [35]. This finding calls attention to our finding of higher odds of T2DM in Andeans even at younger ages since early onset of DM has been linked to more severe and complicated disease [35].

Ecuadorian and Bolivian women have higher likelihood T2DM than native women, whereas Peruvian and Colombian men have lower odds of T2DM than the native men. Interestingly, international comparisons show that among the countries considered here, Colombian women are the only with higher DM prevalence than Spanish women and that Andeans men have lower prevalence than Spanish men [32]. The US study examining the association of country of birth with DM according to sex found similar odds of DM for South American men and women when compared with Mexicans [30]. Our findings underscore the need to examine DM not only for country of birth but also by sex to elucidate possible differences within and between the immigrant and native population.

When considering length of residence, Andeans who live in Madrid for at least 11 years have a significantly higher probability of T2DM than natives. While comparisons with previous studies are difficult due to different methodologies or the focused on different origins [22, 24, 30], our findings are consistent with previous studies showing higher T2DM prevalence as length of residence increases. It is worth noting that only two of these studies have included South Americans [30, 36] with one of them finding that a higher odds of DM in those with 10 or more years relative to those with less than 10 years in the USA [30]. In Spain, few studies have consistently shown poor outcomes among immigrants with longer length of residence for perceived health [37], obesity [38] and multimorbidity [39]. However, these studies did not show data disaggregated by country of birth or relative to natives.

While studies have included length of residence as a measure of acculturation, these studies are unable to explain their finding of worse outcomes as length of residence increases [36, 40]. However, it is possible that structural and socioeconomic factors and conditions related to health outcomes such as structural inequality, social mobility and socioeconomic position [41] may affect immigrants in the host country contributing negatively to their health status as time to such exposure increases. While more studies on immigrant populations’ health are still needed [42], as well as the best strategies to addresses it [43], this study provides a specific look at an important population group in Spain and Europe.

Several limitations to this study must be considered including some unique to the use of an administrative database. First, while we use the best proxy available for length of residence for immigrants, it is possible that length of residence may be underestimated as not all immigrants register right away with the NHDM. The latter may have underestimated our results. Second, it is possible that some irregular immigrants (illegal immigrants) may be unrepresented because the Spanish Royal Decree-Law 16/2012 limited their access to health care in 2012. However, in 2014, Madrid expanded its coverage, including people with chronic conditions, besides several primary health care centers opposed this action. Third, information on important covariates was missing. For instance, we could not adjust for potential confounders, like BMI or use of the service, as data were not available. Despite these limitations, this study relies on a large sample including data from the whole population of Madrid city [9]. This is especially relevant when studying immigrant populations as it allowed us to assess not only country-specific subgroups but also effect measure modifiers by age, sex and length of residence. Another strength is the representation of all primary health care centers of Madrid city. Finally, this is the only study in Spain and Europe showing the T2DM prevalence in Andean immigrant populations as a whole and disaggregated by country of birth. These findings emphasize the importance of studying immigrant population in a detailed and disaggregated manner and may suggest the need for specific clinical and preventive approaches for this population.

References

Harding JL, Pavkov ME, Magliano DJ et al (2018) Global trends in diabetes complications: a review of current evidence. Diabetologia 62:3–16

Ogurtsova K, Da-Rocha-Fernandes JD, Huang Y et al (2017) IDF Diabetes Atlas: global estimates for the prevalence of diabetes for 2015 and 2040. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 128:40–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2017.03.024

IDF (2017) Diabetes atlas. International Diabetes Federation, Brussels

Soriguer F, Goday A, Bosch-Comas A et al (2012) Prevalence of diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose regulation in Spain: the Di@bet.es Study. Diabetologia 55:88–93

Gandarillas A, Del Pino V, Ordobas et al (2016) Prevalence and evolution of the Diabetes Mellitus in the Community of Madrid: PREDIMERC Study 2. Gac Sanit 30:127. In: XXXIV Scientific Meeting of the Spanish Society of Epidemiology and XI Congress of the Portuguese Association of Epidemiology. Sevilla, 14–16 Sept 2016

Dagenais GR, Gerstein HC, Zhang X et al (2016) Variations in diabetes prevalence in low-, middle-, and high-income countries: results from the prospective urban and rural epidemiological study. Diabetes Care 39:780–787

Rechel B, Mladovsky P, Ingleby D et al (2013) Migration and health in an increasingly diverse Europe. Lancet 381:1235–1245

Menozzi C (2016) International migration report: 2015. United Nations

INE®: Instituto Nacional de Estadística. www.ine.es. Accessed 23 Dec 2019

Comunidad Andina (2018) Comunidad Andina. Official web site of the Andean Community. www.comunidadandina.org. Accessed 23 Dec 2019

Abate N, Chandalia M (2003) The impact of ethnicity on type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Complic 17:39–58

Testa R, Bonfigli AR, Genovese S, Ceriello A (2016) Focus on migrants with type 2 diabetes mellitus in European countries. Intern Emerg Med 11:319–326

Oza-Frank R, Stephenson R, Venkat Narayan KM (2011) Diabetes prevalence by length of residence among US immigrants. J Immigr Minor Health 13:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-009-9283-2

Menigoz K, Nathan A, Turrell G (2016) Ethnic differences in overweight and obesity and the influence of acculturation on immigrant bodyweight: evidence from a national sample of Australian adults. BMC Public Health 16:1–13

Last J (2007) A dictionary of public health Oxford. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Mckay L, Macintyre S, Ellaway A et al (2003) Migration and health: medical research council social and public health sciences unit migration and health: a review of the International literature. International Organization of Migration

Renzaho A, Polonsky M, Mellor D, Cyril S (2016) Addressing migration-related social and health inequalities in Australia: call for research funding priorities to recognise the needs of migrant populations. Aust Heal Rev 40:3–10

International Organization for Migration, The UN Migration Agency (2018) Social determinants of migrant health. https://www.iom.int/social-determinants-migrant-health. Accessed 23 Dec 2019

Franch-Nadal J, Martinez-Sierra MC, Espelt A et al (2013) The diabetic immigrant: cardiovascular risk factors and control. Contributions of the IDIME Study. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 66:39–46

Soler-González J, Marsal JR, Serna C et al (2013) Poorer diabetes control among the immigrant population than among the autochthonous population. Gac Sanit 27:19–25

Esteban-Vasallo MD, Dominguez-Berjon MF, Astray-Mochales J et al (2009) Prevalence of diagnosed chronic disorders in the immigrant and autochthonous population. Gac Sanit 23:548–552

De Burgos-Lunar C, Salinero-Fort MA, Cárdenas-Valladolid J et al (2011) Validation of diabetes mellitus and hypertension diagnosis in computerized medical records in primary health care. BMC Med Res Methodol 11:1–11

Gil Montalbán E, Ortiz Marrón H, López-Gay Lucio-Villegas D et al (2014) Validity and concordance of electronic health recors in primary care (AP-Madrid) for surveillance of diabetes mellitus. PREDIMERC study. Gac Sanit 28:393–396

Esteban-Vasallo MD, Dominguez-Berjon MF, Astray-Mochales J et al (2009) Epidemiological usefulness of population-based electronic clinical records in primary care: estimation of the prevalence of chronic diseases. Fam Pract 26:445–454. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmp062

Zoni AC, Domínguez-Berjón MF, Esteban-Vasallo MD et al (2018) Injuries among immigrants treated in primary care in Madrid, Spain. J Immigr Minor Health 20:456–464

Bilal U, Díez J, Alfayate S et al (2016) Population cardiovascular health and urban environments: the Heart Healthy Hoods exploratory study in Madrid, Spain. BMC Med Res Methodol 16:1–12

Madrid Department of Health (2017) Report on the state of health of the population of the community of Madrid 2017

Menigoz K, Nathan A, Turrell G (2016) Ethnic differences in overweight and obesity and the influence of acculturation on immigrant bodyweight: evidence from a national sample of Australian adults. BMC Public Health 16:932. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3608-6

American Diabetes Association (ADA) (2015) Standards of medical care in diabetes. Diabetes Care 38:S10

Commodore-Mensah Y, Ukonu N, Obisesan O et al (2016) Length of residence in the United States is associated with a higher prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors in immigrants: a contemporary analysis of the National Health Interview Survey. J Am Heart Assoc 5:1–10

Oza-Frank R, Narayan KMV (2010) Overweight and diabetes prevalence among US immigrants. Am J Public Health 100:661–668

World Health Organization (2016) Diabetes country profiles 2016. http://www.who.int/diabetes/country-profiles/en/. Accessed 23 Dec 2019

Bustillo RMDE, Antón J (2010) From the Spain that emigrates to the Spain that hosts: context, dimension and characteristics of Latin American immigration in Spain. Am Lat Hoy 55:15–39

Vono D, Bayona-i-Carrasco J (2010) The residential settlement of Latin Americans in the main Spanish cities (2001-2009). United Nations, Chile

Tenkorang EY (2017) Early onset of type 2 diabetes among visible minority and immigrant populations in Canada. Ethn Health 22:266–284

Kandula NR, Diez-Roux Av, Chang C et al (2008) Association of acculturation levels and prevalence of diabetes in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Diabetes Care 31:1621–1628

Salinero-Fort MA, Jiménez-García R, Otero-Sanz L et al (2012) Self-reported health status in primary health care: the influence of immigration and other associated factors. PLoS ONE 7:1–10

Marín-Guerrero A, Rodriguez-Artalejo F, Guallar P et al (2015) Association of the duration of residence with obesity-related eating habits and dietary patterns among Latin-American immigrants in Spain. Br J Nutr 113:343–349

Gimeno-Feliu LA, Calderón-larrañaga A (2017) Multimorbidity and immigrant status: associations with area of origin and length of residence in host country. Fam Pract 34:662–666

Pasupuleti SS, Jatrana S, Richardson K (2015) Effect of nativity and duration of residence on chronic health conditions among Asian immigrants in australia: a longitudinal investigation. J Biosoc Sci 48:322–341

Zambrana R, Carter-Pokras O (2010) Role of acculturation research in advancing science and practice in reducing health care disparities among Latinos. Am J Public Health 100:18–23

Friedrich M, Glaesmer H, Nesterko Y, Turrio CM (2018) Trajectories of health-related quality of life in immigrants and non-immigrants in Germany: a population-based longitudinal study. Int J Public Health 64:49–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-018-1113-7

Razum O, Spallek J (2014) Addressing health-related interventions to immigrants: migrant-specific or diversity-sensitive? Int J Public Health 59:893–895. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-014-0584-4

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the University of Alcala, Madrid, Spain and the City University of New York Graduate School of Public Health and Health Policy, New York, United States, and all researchers who work in the health of immigrants, of whom we are learning and using their knowledge.

Funding

The Heat Healthy Hoods Project (HHH Project) was funded by the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007_2013/ERC Starting Grant Heart Healthy Hoods Agreement No. 336893). M. Franco is the principal investigator of HHH Project. A.B. Bonilla is a researcher in the HHH project and was supported by a scholarship from the University of Alcala, Madrid, Spain.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ABB-E, LNB, MF and IDC-G were responsible for the conception, design, analysis and interpretation of data. ABB-E prepared the first draft of the manuscript with help of LNB, MF and IDC-G. All the authors were involved in critical revisions of the manuscript. LS-P contributed with data extraction process. All authors read and approved the final version for publication. ABB-E and LNB are the guarantors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical standard

All procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Madrid Region Clinical Research Ethics Committee ERC-2013-StG-336893, the Central Research Commission of the PHM HHH-15-15 and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was developed as stipulated in the Spanish Organic Law 15/1999 on the Protection of Personal Data.

Informed consent

This is a register-based study with anonymous data and no patient contacts. Thus, no informed consent was required for this study.

Additional information

Managed by Massimo Porta.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bonilla-Escobar, B.A., Borrell, L.N., Del Cura-González, I. et al. Type 2 diabetes prevalence among Andean immigrants and natives in a Southern European City. Acta Diabetol 57, 1065–1072 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-020-01515-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-020-01515-7