Abstract

Introduction

Surgical intervention is the treatment of choice in patients with thoracic disc herniation with refractory symptoms and progressive myelopathy. Due to high occurrence of complications from open surgery, minimally invasive approaches are desirable. Nowadays, endoscopic techniques have become increasingly popular and full-endoscopic surgery can be performed in the thoracic spine with low complication rates.

Methods

Cochrane Central, PubMed, and Embase databases were systematically searched for studies that evaluated patients who underwent full-endoscopic spine thoracic surgery. The outcomes of interest were dural tear, myelopathy, epidural hematoma, recurrent disc herniation, and dysesthesia. In the absence of comparative studies, a single-arm meta-analysis was performed.

Results

We included 13 studies with a total of 285 patients. Follow-up ranged from 6 to 89 months, age from 17 to 82 years, with 56.5% male. The procedure was performed under local anesthesia with sedation in 222 patients (77.9%). A transforaminal approach was used in 88.1% of the cases. There were no cases of infection or death reported. The data showed a pooled incidence of outcomes as follows, with their respective 95% confidence intervals (CI)—dural tear (1.3%; 95% CI 0–2.6%); dysesthesia (4.7%; 95% CI 2.0–7.3%); recurrent disc herniation (2.9%; 95% CI 0.6–5.2%); myelopathy (2.1%; 95% CI 0.4–3.8%); epidural hematoma (1.1%; 95% CI 0.2–2.5%); and reoperation (1.7%; 95% CI 0.1–3.4%).

Conclusion

Full-endoscopic discectomy has a low incidence of adverse outcomes in patients with thoracic disc herniations. Controlled studies, ideally randomized, are warranted to establish the comparative efficacy and safety of the endoscopic approach relative to open surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Minimally invasive techniques require significantly less tissue manipulation and, therefore, cause less collateral tissue damage during the surgery. This has been shown to minimize local and systemic inflammation and iatrogenic muscle injury [1,2,3]. Since the introduction of working-channel endoscopic spine surgery in 1980s for the treatment of lumbar disc herniations, its indications have rapidly expanded [4]. They have been used in the treatment of cervical foraminal stenosis, cervical disc herniations, and thoracic disc herniations [5,6,7,8,9].

Disc herniations in the cervical and lumbar spine are common conditions, whereas disc herniations in the thoracic spine are thought to be relatively rare. The annual incidence of symptomatic thoracic disc herniations (TDH) is reported to range from 0.0001 to 0.1% of the general population with a peak incidence occurring in the fourth decade [10, 11]. Emerging evidence suggests that TDH may be more common than previously thought [12]. TDH tends to occur more frequently in males, and T8–9 is the most affected level. TDHs occur centrally in most cases (66%), whereas the remaining are paramedian. Most cases are asymptomatic, and surgical management is indicated infrequently [13].

Traditional surgery for TDH includes laminectomy or discectomy, performed through many different access options, such as transpedicular or costotransversectomy. Although effective, these techniques are susceptible to complications, such as risk of injury to the magna radicular artery and spinal cord infarction, resulting in paraplegia [14]. Overall, complications from open surgery in TDH are reported to occur in over 25% of patients [15]. Recently, endoscopic surgery has emerged as a potential alternative for selective patients with TDH.

Given the increasing number of endoscopic surgeries for thoracic spine pathologies and the relatively low number of patients in individual reports, we aimed to perform a meta-analysis to pool outcomes of patients who underwent surgery for TDH through a full-endoscopic approach.

Material and methods

Eligibility criteria and data extraction

We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies that reported outcomes in patients undergoing surgery for thoracic disc herniation (TDH) through a full-endoscopic approach. We restricted inclusion to studies published in English. We excluded case reports and small case series (≤ 3 patients). There were no other restrictions based on study design or time of publication. Patients with cervical or lumbar disc herniations were excluded, as were cases with endoscopic-assisted procedures without a full-endoscopic approach, as defined below. Two reviewers independently screened titles, abstracts, and the full text of selected articles for data extraction following predefined search criteria. Disagreements were solved by consensus.

Search strategy

A systematic search of PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials was performed for studies that met inclusion criteria published until June 2022. To maximize sensitivity of our search, we elected to use a broad search strategy, as follows: (endoscopic OR endoscopy) AND ("disc herniation" OR "disc herniations").

Endpoints and definitions

We extracted the following outcomes from individual studies that met inclusion criteria: dural tear, myelopathy, epidural hematoma, dysesthesia, need for reoperation, and recurrent thoracic disc herniation.

As defined by AOSpine Consensus Paper on Nomenclature for Working-Channel Endoscopic Spinal Procedures, “full endoscopic” should be applied to describe procedures performed with a working-channel endoscope [16]. This distinguishes full-endoscopic procedures from “endoscope-assisted” operations, where tools are passed through trajectories separate from the endoscope. Only studies with a full-endoscopic approach were considered in this meta-analysis.

Statistical analyses

Meta-analysis was performed according to the recommendations of the Cochrane Collaboration and in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis statement [17]. It was performed with Open Meta, an open-source platform for advanced meta-analysis. Pooled estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were computed with random effects model [18].

Risk of bias assessment

Given the single-arm nature of this study, without a comparison group, we utilized the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Case Series to perform risk of bias assessment [19]. The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) is an international, membership-based research and development organization within the Faculty of Health Sciences at the University of Adelaide. The purpose of this appraisal is to assess the methodological quality of a study and to determine the extent to which a study has addressed the possibility of bias in its design, conduct, and analysis. The checklist consists of ten questions ranging from criteria for inclusion, selections of participants, reported about demographic, clinical and follow-up information, and statistical analysis. The answers can be yes, no, unclear, or not applicable. A response of “no” to any of the questions negatively impacts the quality of the study.

Results

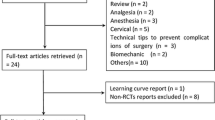

There were 3,299 studies that met search criteria, of which 2,429 were not related to the study question based on title/abstract review. There were 822 duplicate reports in the databases. Forty-eight studies were fully screened and assessed for potential inclusion. Of these, 13 articles were included in the meta-analysis after full review of the manuscript for inclusion and exclusion criteria (Fig. 1). There were 285 patients included, with age ranging from 17 to 82 years, and 56.2% were male (Table 1). The time of follow-up varied between 6 and 89 months. Axial pain was present in 131 (45.9%) patients, and 92 (32.2%) had sings of myelopathy.

Full-endoscopic surgery for TDH was performed through a transforaminal approach in 251 cases (88.1%), interlaminar in 25 (8.8%), and transthoracic extrapleural in 9 (3.1%). Local anesthesia was applied in 222 patients (77.9%). Operative time ranged from 35 to 255 min and was heavily dependent on the number of levels involved, aspect of disc herniation, and the presence of associated pathology, such as ligament flavum ossification or cyst (Table 1).

The data showed a pooled incidence of outcomes as follows: dural tear (1.3%; 95% CI 0–2.6%; Fig. 2); dysesthesia (4.7%; 95% CI 2.0–7.3%; Fig. 3); recurrent disc herniation (2.9%; 95% CI 0.6–5.2%; Fig. 4); myelopathy (2.1%; 95% CI 0.4–3.8%; Fig. 5); epidural hematoma (1.1%; 95% CI 0.2–2.5%; Fig. 6); and reoperation (1.7%; 95% CI 0.1–3.4%; Fig. 7). Blood loss ranged from 20 to 90 mL, and no blood transfusion was necessary in any patient. Hospital length of stay ranged from 0.25 to 8 days. No cases of infections or mortality were related.

Quality assessment of individual studies is reported in Table 2. All studies had a clear outline of the inclusion criteria for patient selection. The last question of the JBI tool inquires whether the correct statistical method was applied. More than two-thirds of studies had an “unclear” answer to this question, which is justified by the single-arm nature of most included studies.

Discussion

In this meta-analysis of 13 studies with 285 patients who underwent surgery for TDH with a full-endoscopic approach, the incidence of surgical complications was low. Dysesthesia was the most common complication, observed in 4.7% of cases in the pooled patient data. The occurrence of recurrent disc herniation and reoperation were only 2.9% and 1.7%, respectively, in a range of follow-up from 6 to 89 months. Overall, these rates compare favorably with another minimally invasive technique. A meta-analysis of 545 patients who underwent minimally invasive thoracoscopic discectomy found an overall complication rate of 24%, including 6% of intercostal neuralgia; 22 patients (4%) required reoperation [20].

Full-endoscopic spine surgery is performed through a working-channel endoscope, either with a transforaminal or interlaminar approach, similar to the approach for lumbar spine [21,22,23]. Full-endoscopic spine surgery provides high-resolution, off-axis visualization of the surgical field and is associated with a low rate of perioperative and postoperative complications compared with minimally invasive spine surgery or traditional spine surgery [24].

Incidental durotomy in patients undergoing laminectomy has been associated with increased blood loss, operative time, and length of stay, albeit with no impact differences in the incidence of nerve root injury, mortality, or need for additional surgeries in long-term follow-up. [25] In our meta-analysis, there was a pooled incidence of dural tear in 1.3% of patients undergoing surgery for TDH with a full-endoscopic approach, with a 95% CI ranging from 0 to 2.6%. In two of the five cases in this series, the TDHs were calcified. Central calcified TDH presents a surgical challenge as intradural lesions are frequently encountered with high rate of adhesion to the dura, leading to elevated rates of cerebrospinal fluid leaks that are difficult to manage with minimally invasive techniques such as thoracoscopy or mini-open thoracotomy [26, 27]. McCormick et al. found a 15% rate of dural breach in patients operated with traditional spine surgery for thoracic disc disease [28]. Wait et al. reported six (4.9%) breaches out of 121 thoracoscopy cases, all treated by lumbar drainage [29].

The intradural component at the thoracic spine has many rootlets and less cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which has important role as a buffer. Therefore, this region is more susceptible to heat injury with the use of laser [30, 31]. Direct nerve injury has also been reported with an incidence of 0–1.5% in lumbar endoscopic procedures, which may happen in the thoracic region also [32,33,34]. Both mechanisms, i.e., the direct injury or heat injury, can cause dysesthesia. We found a 4.7% (95% CI 2.0–7.3%) pooled incidence of dysesthesia after a full-endoscopic approach for TDH. It is important to highlight that two-thirds were transient. Intercostal neuralgia is a common complication of traditional spine surgery, especially in approach that involves rib resection, with a reported rate in the literature ranging from 17 to 21% [35, 36]. In fact, under a full-endoscopic approach, nerve injury may be monitored with the patient awake, if local anesthesia is performed. In this meta-analysis, local anesthesia was applied in 77.9% of TDH cases operated with a full-endoscopic approach, which is difficult in open approaches.

Incomplete decompression or residual fragment is defined as the clinical persistence of symptoms in the 2 weeks following the postoperative period, without a period of relief of symptoms and, also, with fragment findings in thoracic imaging [37]. Dutzmann et al. [38] reported outcomes on 456 consecutive patients treated for symptomatic TDH; 21 (4.8%) had a prior history of thoracic discectomy, with incompletely excised and symptomatic herniated thoracic discs. In the present study, we found this complication only in five cases among 196 surgeries (2.9%; 95% CI 0.6–5.2%), including one who had recurrent disc herniation only eight months after the procedure.

One significant complication of spine surgery is myelopathy. Myelopathies are caused primarily by compression of the anterolateral funiculus and can show signs of central neurological deficits (e.g., hyperreflexia, gait disorders, paresis, bladder disorders, paraplegia) [39,40,41]. Symptoms of postoperative myelopathy were found in four patients after 274 surgeries (2.1%; 95% CI 0.4–3.8%). Three cases had transient symptoms. One patient with permanent injury had a giant TDH, described as that which displaces more than 40% of the spinal canal [42]. In a review study by Yuan et al. [43], postoperative neurological deterioration developed in 16 of 257 patients (6.2%) who underwent open procedures for thoracic disc disorders.

Postoperative wound hematomas also represent a serious complication with the potential for long-term neurologic sequelae in any spine surgery. A multicenter retrospective review by Sen found an incidence of 0.4% of epidural hematoma after endoscopic spine surgery in total of 553 consecutive cases [44]. Our systematic review found two cases of epidural hematoma in 239 surgeries, with a pooled incidence of 1.1% (95% CI 0.2–2.5%). In one case, a revision was carried out at T1–T2 with removal of the hematoma and subsequent resolution of pain. The other case was treated clinically.

In this meta-analysis, we found only two cases of reoperation (1.7%; 95% CI 0.1–3.4%), for the treatment of epidural hematoma in one patient and for recurrent TDH in the other. Uribe et al. reported three (5%) cases of reoperation among 60 patients who underwent a mini-open lateral approach for the removal of 75 symptomatic TDHs [45]. The second endoscopic procedure, in reoperation cases, was satisfactory. This suggests that endoscopic spine surgery may be safe for revision surgery as well. A recent study with forty-eight patients who underwent revision full-endoscopic spine surgery (at 60 levels) under local anesthesia found no significant difference in operating time, intraoperative blood loss, or complication rates between revision full-endoscopic spine surgery and primary full-endoscopic spine surgery [46].

Surgical site infection (SSI) is the third most common complication after spinal surgery [47,48,49]. In the USA, this has resulted in direct and indirect medical expenditure amounting from 1 to 10 billion, with 8000 deaths per year [50]. Treatment of SSI often requires multiple readmissions, wound debridement or implant removal, and prolonged antibiotic therapy [51]. It increases hospital readmissions, worsens outcomes, and adds additional costs [52]. In this meta-analysis, there were no cases of SSI. In the study by Uribe et al., there was one case (1.7%) of SSI among 60 patients operated for TDH with a minimally invasive lateral approach [45]. Blood transfusion was not necessary in any patient, and there were no deaths reported in our report.

This meta-analysis had significant limitations. Most importantly, the single-arm nature of this meta-analysis precludes a definitive comparison of the full-endoscopic approach with other surgical techniques. In addition, despite the pooling of 13 studies, some studies had small patient populations. Finally, the time of postoperative follow-up was variable between the studies. Nevertheless, heterogeneity of statistical results was low.

Conclusion

Minimally invasive techniques have brought a paradigm shift in the management of cervical/lumbar spinal conditions, and similar techniques have been extrapolated to the thoracic region as well. Full-endoscopic discectomy has a low incidence of adverse outcomes in patients with thoracic disc herniations and can be done safe and effectively. Controlled studies, ideally randomized, are warranted to establish the comparative efficacy and safety of the endoscopic approach relative to open surgery.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence intervals

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- FC:

-

Facet cyst

- IntTL:

-

Interlaminar

- JBI:

-

The Joanna Briggs Institute

- NA:

-

Not available

- OFL:

-

Ossification flavum ligament

- OLLP:

-

Ossification ligament longitudinal posterior

- PS:

-

Posterior stenosis

- SSI:

-

Surgical site infection

- TDH:

-

Thoracic disc herniation

- TEP:

-

Transthoracic retropleural

- TrSF:

-

Transforaminal

References

Sasaoka R, Nakamura H, Konishi S et al (2006) Objective assessment of reduced invasiveness in MED. Compared with conventional one level laminotomy. Eur Spine J 15:577–582

Schick U, Dohnert J, Richter A, Konig A, Vitzthum HE (2002) Microendoscopic lumbar discectomy versus open surgery: an intraoperative EMG study. Eur Spine J 11:20–26

Shin DA, Kim KN, Shin HC, Yoon DH (2008) The efficacy of microendoscopic discectomy in reducing iatrogenic muscle injury. J Neurosurg Spine 8:39–43

Kambin P, Sampson S (1986) Posterolateral percutaneous suction-excision of herniated lumbar intervertebral discs. Report of interim results. Clin Orthop Relat Res 207:37–43

Wagner R, Telfeian AE, Iprenburg M, Krzok G (2017) Minimally invasive fully endoscopic two-level posterior cervical foraminotomy: technical note. J Spine Surg 3:238–242

Ye ZY, Kong WJ, Xin ZJ, Fu Q, Ao J, Cao GR et al (2017) Clinical observation of posterior percutaneousfull-endoscopic cervical foraminotomy as a treatment for osseous foraminal stenosis. World Neurosurg 106:945–952

Ruetten S, Komp M, Merk H, Godolias G (2008) Fullendoscopic cervical posterior foraminotomy for the operation of lateral disc herniations using 59-mm endoscopes: a prospective, randomized, controlled study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 33:940–948

Park JH, Jun SG, Jung JT, Lee SJ (2017) Posterior percutaneous endoscopic cervical foraminotomy and diskectomy with unilateral biportal endoscopy. Orthopedics 40:e779–e783

Wagner R, Telfeian AE, Iprenburg M, Krzok G, Gokaslan Z, Choi DB et al (2016) Transforaminal endoscopic foraminoplasty and discectomy for the treatment of a thoracic disc herniation. World Neurosurg 90:194–198

Brown CW, Deffer PA, Akmakjian J et al (1992) The natural history of thoracic disc herniation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 17:97–102

Yoshihara H, Yoneoka D (2014) Comparison of in-hospital morbidity and mortality rates between anterior and nonanterior approach procedures for thoracic disc herniation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 39:728–33

Cornips EMJ, Janssen MLF, Beuls EAM (2011) Thoracic disc herniation and acute myelopathy: clinical presentation, neuroimaging findings, surgical considerations, and outcome. J Neurosurg Spine 14:520–528

Sharma SB, Kim JS (2019) A review of minimally invasive surgical techniques for the management of thoracic disc herniations. Neurospine 16:24–33

Shlobin NA, Raz E, Shapiro M et al (2020) Spinal neurovascular complications with anterior thoracolumbar spine surgery: a systematic review and review of thoracolumbar vascular anatomy. Neurosurg Focus 49(3):E9

Gibson RDS, Wagner R, Gibson JNA (2021) Full endoscopic surgery for thoracic pathology: an assessment of supportive evidence. EFORT Open Rev 6(1):50–60

Hofstetter CP, Ahn Y, Choi G, Gibson JNA et al (2020) AOSpine consensus paper on nomenclature for working-channel endoscopic spinal procedures. Glob Spine J 10(2S):111S-121S

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the prisma statement. BMJ 339:b2535

Meta-Analyst O. Open Meta-Analyst – The tool|Evidence synthesis in health. https://www.brown.edu/academics/public-health/research/evidence-synthesis-in-health/open-meta-analyst-tool. Accessed 25 July 2022. www.cebm.brown.edu/openmeta.

Moola S, Munn Z, Tufanaru C, Aromataris E, Sears K, Sfetcu R, Currie M, Qureshi R, Mattis P, Lisy K, Mu PF (2017) Joanna Briggs institute reviewer’s manual. The Joanna Briggs Institute. Available from https://joannabriggs.org.

Elhadi AM, Zehri AH, Zaidi HA, Almefty KK, Preul MC, Theodore N et al (2015) Surgical efficacy of minimally invasive thoracic discectomy. J Clin Neurosci 22:1708–1713

Krzok G (2020) Transforaminal endoscopic surgery: outside-in technique. Neurospine 17(Supplement 1):S44–S57

Chung AS, Wang JC (2020) Introduction to endoscopic spinal surgery. Neurospine 17(Supplement 1):S1–S2

Chung AS, Wang JC (2020) The rationale for endoscopic spinal surgery. Neurospine 17(Supplement 1):S9–S12

Sen RD, White-Dzuro G, Ruzevick J et al (2018) Intra- and perioperative complications associated with endoscopic spine surgery: a multi-institutional study. World Neurosurg 120:e1054–e1060

Desai A, Ball PA, Bekelis K, Lurie J, Mirza SK, Tosteson TD, et al (2015) SPORT: does incidental durotomy affect long-term outcomes in cases of spinal stenosis? Neurosurgery 76(Suppl 1):S57–63 discussion S63.

Gille O, Soderlund C, Razafimahandri HJC, Mangione P, Vital MC (2006) Analysis of hard thoracic herniated discs: review of 18 cases operated by thoracoscopy. Eur Spine J 15:537–542

Moran C, Ali Z, McEvoy L, Bolger C (2012) Mini-open retropleural transthoracic approach for the treatment of giant thoracic disc herniation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 37:E1079–E1084

McCormick WE, Will SF, Benzel EC (2000) Surgery for thoracic disc disease. Complication avoidance: overview and management. Neurosurg Focus 9:e

Wait SD, Fox DJ, Kenny KJ, Dickman C (2012) Thoracoscopic resection of symptomatic herniated thoracic discs. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 37:35–40

Choi G, Pophale CS, Patel B et al (2017) Endoscopic spine surgery. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 60:485–497

Kim DH, Choi G, Lee SH (2011) Endoscopic spine procedures. Thieme Medical Publishers, New York

Chen X, Chamoli U, Lapkin S et al (2019) Complication rates of different discectomy techniques for the treatment of lumbar disc herniation: a network meta-analysis. Eur Spine J 28:2588–2601

Xie TH, Zeng JC, Li ZH et al (2017) Complications of lumbar disc herniation following full-endoscopic interlaminar lumbar discectomy: a large, single-center, retrospective study. Pain Physician 20:E379–E387

Shriver MF, Xie JJ, Tye EY et al (2015) Lumbar microdiscectomy complication rates: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurg Focus 39:E6

Le Roux PD, Haglund MM, Harris AB (1993) Thoracic disc disease: experience with the transpedicular approach in twenty consecutive patients. Neurosurgery 33:58–66

Currier BL, Eismont FJ, Green BA (1994) Transthoracic disc excision and fusion for herniated thoracic discs. Spine 19:323–328

Lee SH, Kang BU, Ahn Y et al (2006) Operative failure of percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy: a radiologic analysis of 55 cases. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 31:E285–E290

Dützmann S, Rose R, Rosenthal D (2020) Revision surgery in thoracic disc herniation. Eur Spine J 29(Suppl 1):39–46

Quint U, Bordon G, Preissl I, Sanner C, Rosenthal D (2012) Thoracoscopic treatment for single level symptomatic thoracic disc herniation: a prospective followed cohort study in a group of 167 consecutive cases. Eur Spine J 21:637–645

Radecki J, Feinberg JH, Zimmer ZR (2009) T1 radiculopathy: electrodiagnostic evaluation. HSS J 5:73–77

Roelz R, Scholz C, Klingler JH, Scheiwe C, Sircar R, Hubbe U (2016) Giant central thoracic disc herniations: surgical outcome in 17 consecutive patients treated by mini-thoracotomy. Eur Spine J 25:1443–1451

Hott JS, Feiz-Erfan I, Kenny K, Dickman CA (2005) Surgical management of giant herniated thoracic discs: analysis of 20 cases. J Neurosurg Spine 3:191–197

Yuan L, Chen Z, Li W et al (2021) Risk factors associated with post-operative neurological deterioration in patients with thoracic disc disorders with myelopathy. Int Orthop 45(6):1539–1547

Sen RD, White-Dzuro G, Ruzevick J, Kim CW, et al (2018) Intra- and perioperative complications associated with endoscopic spine surgery: a multi-institutional study. World Neurosurg e1–e7

Uribe JS, Smith WD, Pimenta L, Härtl R et al (2012) Minimally invasive lateral approach for symptomatic thoracic disc herniation: initial multicenter clinical experience. J Neurosurg Spine 16:264–279

Yagi K, Kishima K, Tezuka F, et al (2022) Advantages of revision transforaminal full-endoscopic spine surgery in patients who have previously undergone posterior spine surgery. J Neurol Surg A Cent Eur Neurosurg

Saeedinia S, Nouri M, Azarhomayoun A et al (2015) The incidence and risk factors for surgical site infection after clean spinal operations: A prospective cohort study and review of the literature. Surg Neurol Int 6:154

Lonjon G, Dauzac C, Fourniols E et al (2012) Early surgical site infections in adult spinal trauma: a prospective, multicentre study of infection rates and risk factors. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res OTSR 98:788–794

Lonjon G, Dauzac C, Fourniols E et al (2012) Early surgical site infections in adult spinal trauma: a prospective, multicentre study of infection rates and risk factors. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res OTSR 98:788–794

Hidron AI, Edwards JR, Patel J et al (2008) NHSN annual update: antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: annual summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006–2007. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 29:996–1011

Hedequist D, Haugen A, Hresko T et al (2009) Failure of attempted implant retention in spinal deformity delayed surgical site infections. Spine 34:60–64

Anderson PA, Savage JW, Vaccaro AR et al (2017) Prevention of surgical site infection in spine surgery. Neurosurgery 80:S114–S123

Bae J, Chachan S, Shin S, Lee S (2020) Transforaminal endoscopic thoracic discectomy with foraminoplasty for the treatment of thoracic disc herniation. J Spine Surg 6(2):397–404

Cheng XK, Chen B (2020) Percutaneous endoscopic thoracic decompression for thoracic spinal stenosis under local anesthesia. World Neurosurg 139:488–494

Choi K, Eun S, Lee S, Lee H (2010) Percutaneous Endoscopic Thoracic Discectomy; Transforaminal Approach. Minim Invasive Neurosurg 53(1):25–28

Gao S, Wei J, Li W, et al (2021) Full-endoscopic transforaminal ventral decompression for symptomatic thoracic disc herniation with or without calcification: technical notes and case series. Pain Res Manag 3

Houra K, Saftic R, Knight M (2021) Five-year outcomes after transforaminal endoscopic foraminotomy and discectomy for soft and calcified thoracic disc herniations. Int J Spine Surg 15(3):494–503

Lin W, Liu W, Ma WT, Xue Y (2021) Per pedicel-ligament flavum tunnel outside-in foraminoplasty for T10–T12 discectomy under a percutaneous endoscope. Orthop Surg 13(1):253–259

Nie HF, Liu KX (2013) Endoscopic transforaminal thoracic foraminotomy and discectomy for the treatment of thoracic disc herniation. Minim Invasive Surg

Ruetten S, Hahn P, Oezdemir S et al (2018) Full-endoscopic uniportal decompression in disc herniations and stenosis of the thoracic spine using the interlaminar, extraforaminal, or transthoracic retropleural approach. J Neurosurg Spine 29:157–168

Shen J, Telfeian A (2020) Fully endoscopic 360° decompression surgery for thoracic spinal stenosis: technical note and report of 8 cases. Pain Physician 23(6):659–663

Xiaobing Z, Xingchen L, Honggang Z et al (2019) U^ route transforaminal percutaneous endoscopic thoracic discectomy as a new treatment for thoracic spinal stenosis. Int Orthop 43(4):825–832

Yuefei L, Rui L, Jiabin R et al (2021) Three-dimensional CT analysis of the treatment of thoracic disc herniation by percutaneous endoscopic posterolateral approach: establishment of a good osseous channel. Zhongguo Zuzhi Gongcheng Yanjiu 25(21):3354–3359

Zhang LM, Lv WY, Cheng G et al (2019) Percutaneous endoscopic decompression for calcified thoracic disc herniation using a novel T rigid bendable burr. Br J Neurosurg 28:1–3

Zhenzhou L, Hongliang Z, Zheng C, Weilin S, Shuxun H (2020) Technical notes and clinical efficacy analysis of full⁃endoscopic thoracic discectomy via transforaminal approach. Natl Med J China 4(100)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors report no relationships that could be construed as a conflict of interest. All authors take responsibility for all aspects of the reliability and freedom from bias of the data presented and their discussed interpretation.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Silva, J.D.S., Carelli, L.E., de Oliveira, J.A.A. et al. Full-endoscopic discectomy for thoracic disc herniations: a single-arm meta-analysis of safety and efficacy outcomes. Eur Spine J 32, 1254–1264 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-023-07595-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-023-07595-7