Abstract

Purpose

The Core Outcome Measure Index (COMI) is a multidimensional questionnaire that investigates five dimensions in low back pain (LBP) patients, but does not address the psychological dimension. As the biopsychosocial perspective is recognized as important to capture the entire clinical picture of these patients, this multicenter prospective cohort study was designed to investigate the psychometric properties of a modified version of the COMI (COMIAD) which included 2 additional items, exploring anxiety and depression, respectively.

Methods

168 subacute or chronic LBP patients recruited in spine clinics completed a set of questionnaires before and after treatment (follow-up at 6 months). Construct validity was explored by comparing each item of the COMIAD to validated full-length questionnaires. Thus two additional questionnaires were included to assess the construct validity of the anxiety and depression measures. The psychometric properties of the COMI and COMIAD were then compared.

Results

The two new items showed good internal consistency, high correlations with the corresponding full-length questionnaires, no floor or ceiling effect and good reproducibility (test–retest agreement kappa 0.68 for anxiety, 0.62 for depression). The addition of the 2 items did not alter internal validity (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.88 and 0.87, respectively). The smallest detectable difference, the Minimal Clinically Important Improvement and the Patient Acceptable Symptom State were only minimally affected by the changes.

Conclusion

The questions exploring anxiety and depression have good intrinsic and psychometric capacities (i.e., no floor or ceiling effects and high correlations with full-length scales) and did not significantly modify the psychometrics of the original COMI questionnaire. The COMIAD offers the possibility to include the psychological dimension in the multidimensional evaluation without significantly affecting questionnaire length.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Many questionnaires are available to appraise various dimensions in low back pain (LBP) patients. The dimensions that were singled out for use in a variety of settings, including routine clinical care, quality management, and research, are pain (back and leg), symptom-specific function, generic well-being, social disability and work disability, along with satisfaction with treatment [1]. The Core Outcome Measures Index (COMI) was originally proposed to condense the measures of these dimensions in a short, easy to use questionnaire [1]. This 7-item quick-to-answer questionnaire was shown to be a reliable and valid [2–4] instrument for assessing multidimensional outcomes for patients suffering from LBP. A sum score from 0 (best health status) to 10 (worst health status) can then be computed. It is routinely used in the SpineTango, the European Spine registry [5].

Such a multidimensional assessment calls upon the biopsychosocial model [6] that has been widely advocated during the last three decades in the conceptualization of the etiology and prognosis of LBP [7]. However, it does not fully consider the identification of psychological risk factors for the development of disability following the onset of LBP as described by the “yellow flags” [8]. Both the biopsychosocial model and the yellow flags emphasize the importance of psychological factors and among those the role of distressed affect. Indeed, as Nicholas et al. [8] pointed in their reappraisal of psychological yellow flags, taken as a whole the evidence shows a clear relationship between these factors and future clinical and occupational outcomes. Among these yellow flags, distress, depressed mood and anxiety were consistently associated with the transition from acute to chronic pain problems [9]. It does actually appear that depression especially is associated with a number of negative outcomes [10]. However, anxiety and depression commonly coexist and when the disorders co-occur, patient disability is greater than when either one alone is present [10, 11]. Much in the same line, studies have highlighted that negative emotions such as anxiety and depression increase the risk for new-onset chronic pain [12] and that these emotions contribute to the deterioration in physical function [13]. Furthermore, the emotional burden of pain and depressive and anxiety disorders, separately or conjointly, is high [10, 14].

These data raise the issue of psychological distress as belonging to core outcomes. Anxiety and depression were selected as indicators of psychological distress because of the large body of literature stressing their impact on, and relevance to, pain and function. Therefore, adding items related to anxiety and depression to the COMI was particularly relevant. However, such modifications could alter the psychometric properties of the questionnaire. This study was set up to explore the psychometric properties of two new items (addressing anxiety and depression, respectively) and the impact of this new version on the psychometric properties of the questionnaire.

Methods

Study design

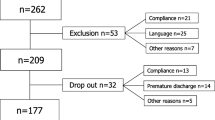

This study was part of a larger research aimed at providing additional knowledge on the psychometric properties of the French version of the COMI by examining the responsiveness of this self-assessment questionnaire to patients’ treatment [15]. A prospective 6-month multicentre cohort study involving patients from non-surgical spine centers was conducted in three French-speaking countries (France, Belgium and Switzerland). Patients were included if they had LBP, with or without radiating leg pain, for at least 4 weeks with an intensity of at least 3 on a 0–10 visual analogue pain scale and were fluent in French. They were excluded if they had a diagnosis of specific LBP (tumor, infection, spondylarthropathy or trauma) or the presence of co-morbidities (e.g., heart failure, knee osteoarthritis) with a functional impact.

During their first appointment to one of the centers for consultation, patients were invited to participate. After having obtained a signed informed consent form, they were instructed to complete a questionnaire booklet (Fig. 1 shows the timeline of the assessment procedure). In addition, a short version of the booklet was given to the patient with the instruction to complete and mail it back to the centre 1 week later for study of reproducibility and reliability (further referred as the short-term follow-up). The follow-up evaluation was scheduled 6 months later (long-term follow-up). The choice of treatment was left to the decision of each investigator. The study was approved by the Medical Ethic Committee of the University Hospitals of Geneva, Switzerland.

Core Outcome Measure Index

The validated French version of the COMI contains 7 questions evaluating 5 dimensions (pain, function, symptom-specific well-being, quality of life and disability) [3, 15]. Two numeric rating scales are used to evaluate back and leg pain and the highest value is used to compute the total score. The other items are rated on 5-point Likert scales. Two questions are used to evaluate social and work disability and the average score is taken to compute the total score. Each of these other items [function, well-being, quality of life, disability (average score of both social and work disability)] is then scaled from 0 to 10, with each incremental step of the 5-point Likert scale being allocated 2.5 points. All five dimension scores [including pain (highest value for either back or leg pain on the numeric rating scale is used)], are thus scaled into a value ranging between 0 (best condition) and 10 (worst condition). A mean score is then computed by the addition of the five subscales divided by five, thus ranging from 0 to 10, and referred to as the sum score [2–4].

Two items, addressing the importance of anxiety and depression during the past week (Table 1), were created and added to the 7 original items, forming the new questionnaire (COMIAD). Their content, i.e., their labeling regarding in particular the examples provided to focus on the issue at stake, was in part inspired by the items of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [16] and answers were on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from ‘not at all’ to ‘extremely’, in congruence with the other items of the COMI [4]. In order to compute the sum score, a “new” item called “psychological distress” was created by retaining the highest value between anxiety and depression. It was then scaled from 0 to 10, to parallel the procedure of the COMI, with each incremental step of the 5-point Likert scale being allocated 2.5 points. Hence, the COMIAD sum score is computed by the addition of the six subscales (pain, function, symptom-specific well-being, general well-being, disability, and psychological distress) divided by six and thus ranges from 0 (‘‘best health status’’) to 10 (‘‘worst health status’’) [4].

Additional assessment

The validated French version of the Roland and Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ) [17], Dallas Pain Questionnaire (DPQ) [18] and Euroquol 5-dimension (EQ-5D), [19]) were used to assess the external validity of the COMI. Two additional questionnaires were included to assess the construct validity of the anxiety and depression measures, i.e., the French validated versions of the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-S/-T) [20–23].

At the short-term follow-up, in addition to the COMIAD, the clinical evolution was evaluated through a question on a 7-point Likert scale (from “strong improvement” to “strong deterioration”).

At the 6-month follow-up, patients were asked to fill in a questionnaire booklet identical to the one received at baseline (Fig. 1); treatments administrated since inclusion were also recorded along with a question evaluating patient’s perceived efficacy assessed on a 5-point Likert scale (from “no effect” to “excellent effect, almost no symptoms at all”). Patients were also asked to state whether they considered their present state as satisfactory through the following statement: “Taking into account all activities you have to perform in your daily life, your amount of pain and the level of physical disability, if you were to remain the same for the next months, would this be acceptable for you?” [24]. This question is central for the determination of patient acceptable symptom state (PASS) [25].

Statistical analysis

According to recommendations [26], a sample size of 150 patients was included. A sample size of 150 patients allows a good analysis of factorial structure of the 7 questions index (>20 patients per question). Detecting an effect size of 0.25 for the improvement in condition between baseline and 6-month follow-up with an alpha of 0.05 and a power of 0.8 requires a sample size of 128. Thus, a sample size of 150 patients is sufficient to detect a small effect size while allowing for a 10 % drop-out. Data entry was checked. Missing data were treated according to the specific recommendations for each questionnaire. COMI scores were computed only when all data were present. The analyses described below are based on published recommendations [26].

Floor and ceiling effects Floor and ceiling effects were determined for each item of the COMI, for the 2 questions on anxiety and depression and for the COMIAD sum score by computing the percentage of answers at both extremities of the total score and each subscale.

Construct validity The external construct validity of the COMIAD was explored investigating correlations between subscales to the corresponding validated full-length questionnaire (e.g., BDI for the depression subscale) using Spearman rank correlation coefficients, corrected for ties. Spearman’s Rho coefficients were interpreted as follows: Rho 0.81–1.0 = excellent, 0.61–0.80 = very good, 0.41–0.60 = good, 0.21–0.40 = fair, and 0–0.20 = poor [27, 28]. Pre-specified hypothesis were made and at least good correlation were expected between COMIAD anxiety subscale and STAI-state and COMIAD depression subscale and BDI. In addition, a better correlation between COMIAD anxiety subscale and STAI-state compared to STAI-trait was postulated. For the sum score, our hypothesis was that the correlation with the total score of the DPQ, a multidimensional questionnaire that also includes psychological domains, would be higher for the COMIAD than for the COMI.

Internal validity The internal validity of the COMIAD score was first assessed using principal component analysis (PCA). PCA determines the number of underlying component in a set of items. Since the COMI is supposed to provide a score for a single dimension, we expect the PCA to yield a single component. Then, reliability of the scale was determined using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient.

Reproducibility Reproducibility was assessed by comparing baseline and short-term follow-up responses among those patients who reported no or only minimal change since inclusion. This was computed using weighted kappa for single item and intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for the total score and using the Bland–Altman plotting method which indicates the smallest detectable difference (SDD; i.e., the amount of detectable change above the random measurement error). The 95 % limits of agreements were calculated by Bland and Altman method [29] defined by the mean of the difference between the 2 measures ± 1.96 times the standard deviation of this difference.

Responsiveness, sensitivity to change and additional characteristics Assessment of the smallest detectable change (SDD) was done by multiplying 1.96 to the difference in score between baseline and the 1-week follow-up among patients declaring no or minimal improvement [27, 30]. The minimal clinically important improvement (MCII) was determined using an anchoring method based on the patient’s assessment of response to treatment at last follow-up through a 5-point Likert scale (0 = no effect, 1 = slight effect, 2 = moderate effect, could be better, 3 = good effect, still with some symptoms, 4 = excellent effect) [31]. These results were then divided in patients for whom the treatment did not provide change (0 and 1) and patients for whom the treatment provided change (2–4) and the threshold was determined by subtracting the mean change score of the group from that of the second group. The relationship between the change in COMIAD sum score and MCII was also assessed using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and the determination of the area under the curve (AUC). The MCII was defined as the value in change in COMIAD sum score providing the coordinates on the ROC curve closest to the top left corner (Euclidian method). The standardized variation of the items and the total score was assessed by effect sizes (mean difference divided by the standard deviation of the change).

Assessment of PASS was determined using an anchoring method based on the patient’s answer to the statement “Taking into account all activities you have to perform in your daily life, your amount of pain and the level of physical disability, if you were to remain the same for the next months, would this be acceptable for you?” [25]. The threshold for PASS was determined as being the 75th ‰ of the COMI sum score at last follow-up of patients answering “yes” to the previous statement [25]. The relationship between the change in COMIAD sum score and the PASS was also assessed using ROC curve and AUC.

Psychometric properties of the version of the COMIAD were then compared to those of the original COMI questionnaire.

Results

Eleven centers recruited 168 patients from May 2009 to June 2010. Four centers recruited 5 or less patients and there were at least 2 centers in each country (France, Belgium and Switzerland) recruiting more than 15 patients. The short-term follow-up questionnaire (for the study of reproducibility) was answered by 138 out of 168 patients at a mean time of 12.8 days, SD 32.0. The long-term follow-up was answered by 142 patients at a mean time of 5.5 months, SD 1.5.

Patients’ characteristics at baseline

Patients (n = 168; Table 2) had a mean (SD) age of 45.5 (12.2) years; there was slightly less male than female (43.9 versus 56.1 %). For the vast majority (82 %), the present episode lasted for more than 3 months. Fifteen percent had symptoms and signs compatible with lumbar radiculopathy. Twenty-five patients had had previous back surgery, discectomy for half of them. Overall, clinical characteristics of the patients (i.e., pain, disability, quality of life) evolved positively between baseline and last follow-up (Table 3).

Floor and ceiling effects

The depression and anxiety items had 2.4 % missing values and at least one item was missing in 4.8 % of the COMI and COMIAD questionnaires (Table 4). No significant floor (1.2 %) or ceiling effects (1.2 %) were observed for COMIAD sum score.

Internal validity

The first component analysis of a PCA of the 6 items explains 59.8 % of variance. While the eigenvalue for the second and third factors were slightly above 1, the screenplot favored a one-factor solution. The reliability, as measured by Cronbach’s alpha, was 0.88.

Construct validity

Concerning the construct validity, all hypotheses were fulfilled (Table 5). The item measuring anxiety had a good correlation with state anxiety, and this association was lower with trait anxiety. The item measuring depression had a very good correlation with the BDI. As expected, the COMIAD sum score had a higher correlation with the DPQ, the STAI and the BDI, than the original COMI sum score.

Reproducibility

Out of the 138 patients who responded to the short-term follow-up questionnaire, 132 answered that they had observed no or minimal change from inclusion and were thus included in the test–retest analysis. Test–retest agreement was acceptable for the anxiety and depression items (weighted kappa 0.68 and 0.62, respectively). The test–retest agreement for the sum score was very high (ICC 0.79 (95 % CI 0.71–0.84).

Responsiveness, sensitivity to change and additional characteristics

The SDD was 1.7 for the anxiety item and 1.9 for the depression item. The SDD was 2.1 for the COMIAD sum score (see Bland and Altman plot of COMIAD score, Fig. 2) and the mean difference between scores among stable patients was very low (<0.5). The MCII for the total score was 2.7 based on the distance to the upper left corner. The AUC for the prediction of patient’s own assessment of response to treatment by the change in COMIAD total score was 0.79, meaning that a patient who is reporting no or slight effect had 79 % chance of having a lower COMIAD sum score than a patient who reported a treatment effect. The effect size of the COMIAD sum score was 0.96.

The patient acceptable symptom state (PASS) for the total score (scale from 0 to 10) was 2.92. This threshold on the COMIAD sum score at the last follow-up correctly classified 90.6 % of the patients who declared being unsatisfied with their present state and 74.3 % of patients reporting being satisfied.

The AUC for the prediction of PASS by the change in COMIAD total score was 0.83 (Fig. 3), meaning that a patient who is unsatisfied has 83 % chance of having a lower COMIAD sum score change than a patient who is satisfied.

Relationship between the change in COMIAD sum score and the patient acceptable symptom state (PASS) assessed using ROC curve analysis. The area under the curve for the prediction of PASS by the change in COMIAD total score was 0.84, meaning that a patient who is unsatisfied has 84 % chance of having a lower COMIAD sum score change than a patient who is satisfied

Comparison between COMIAD and COMI

As measured by Cronbach’s alpha, COMIAD and COMI had similar internal validity (Table 6). Reproducibility, responsiveness and sensitivity to change characteristics were also similar for the 2 versions. However, as expected, the addition of psychological distress measured by anxiety and depression improved construct validity and the association with the Dallas Pain Questionnaire was also higher.

Discussion

The COMI is a well validated multidimensional questionnaire that is extremely useful both in clinic and in research because it is short, easy to use and enables to explore several dimensions [4, 5]. One of its limitations could be the absence of the psychological dimension, an important element of the biopsychosocial model used in the field of LBP for more than 20 years. Anxiety and depression are two key psychological aspects and their identification in LBP patients is recommended as their presence may influence therapeutic orientation (e.g., indication to use cognitive-behavioral therapies [32, 33], introduction of antidepressant or anxiolytic medication [34, 35]).

This study demonstrates that the addition of two questions exploring anxiety and depression is important and does not alter the psychometric properties of the questionnaire. Both new items showed good psychometric properties with no floor or ceiling effects and high correlations with full-length scales. Furthermore, MCII and smallest detectable difference remained very similar. Construct validity of the COMIAD was greatly improved not only for depression and anxiety, but also for measures of pain. The PASS for the COMIAD sum score set at 2.92 discriminate satisfied and unsatisfied patients just as well as the COMI sum score, correctly classifying more than 90 % of the patients who declare themselves unsatisfied and 74.3 % of the patients who declared being satisfied after treatments.

To the best of our knowledge, the only other multidimensional self-administered questionnaire specifically developed to assess severity and treatment efficacy in LBP patients is the DPQ [36]. The 16-item DPQ evaluates the impact of LBP on four aspects of daily life, i.e., daily activities, work and leisure activities, anxiety/depression, and social interest. The questionnaire provides 4 scores for each aspect (0–100), but it is not designed to provide a total score like the COMIAD. Furthermore, the values of SDD, MCII and PASS have not yet been established and the DPQ includes twice the number of items as compared to the COMIAD.

The strength of this study is its multicentre setting that includes several French-speaking countries, thus increasing the generalizability of our results. Each new item had its external validity controlled by a well-known and fully validated questionnaire in their respective field of anxiety and depression. But this study does not solve definitively the question of anxiety and depression as core outcomes or as predictors of LBP even if their importance among psychological risk factors has been largely acknowledged [37–39]. In a multicausal perspective, the identification of a factor as a predictor at one stage does not preclude the possibility that this factor may also be a consequence of pain. A biopsychosocial perspective on the onset and evolution of LBP [7] provides ample justification for the role of anxiety and depression at the various stages of the LBP process and as a possible outcome measure of a specific treatment for LBP. The introduction of anxiety and depression in the COMI increases the construct validity of the instrument for the measures of pain, thus providing further ground for the investigation of these variables in the clinical context. In particular, the inclusion of psychological distress in the COMI may increase the ability of the COMI to predict return to work or, conversely, longer sickness leaves [38, 40]. It may also increase the ability of the COMI to predict treatment effects [14, 39, 41, 42], in particular in those situations where yellow flags and the distressed affect can hinder treatment benefits, from the assessment phase and through treatment planning and implementation [8].

The limitation of this study is the relatively short time for the last follow-up. The addition of the two items measuring anxiety and depression also requires further investigation in a clinical cohort to investigate more precisely their role in the evaluation of the treatment effects. Further factors referring to the psychological dimension may also deserve consideration, and in particular fear of movement and self-efficacy where treatment explicitly focuses on such variables which may then be part of the core outcomes considered after such specific treatment for back pain.

In conclusion, the COMIAD, a modified version of the COMI that includes 2 additional items exploring psychological dimensions (anxiety and depression), has good psychometrics properties. With this new version of the COMI, researchers and clinicians have now access to a short and easy to answer questionnaire that allows an evaluation that better fits the biopsychosocial paradigm.

References

Deyo RA, Battie M, Beurskens AJ, Bombardier C, Croft P, Koes B, Malmivaara A, Roland M, Von Korff M, Waddell G (1998) Outcome measures for low back pain research. A proposal for standardized use. Spine 23(18):2003–2013

Ferrer M, Pellise F, Escudero O, Alvarez L, Pont A, Alonso J, Deyo R (2006) Validation of a minimum outcome core set in the evaluation of patients with back pain. Spine 31(12):1372–1379 (discussion 1380)

Genevay SS, Cedraschi CC, Marty MM, Rozenberg SS, De-Goumons PP, Faundez AA, Balagu FF, Porchet FF, Mannion AFA (2012) Reliability and validity of the cross-culturally adapted French version of the Core Outcome Measures Index (COMI) in patients with low back pain. Eur Spine J 21(1):130–137

Mannion AF, Elfering A, Staerkle R, Junge A, Grob D, Semmer NK, Jacobshagen N, Dvorak J, Boos N (2005) Outcome assessment in low back pain: how low can you go? Eur Spine J 14(10):1014–1026

Roeder C, Chavanne A, Mannion AF, Grob D, Aebi M (2005) SSE Spine Tango—content, workflow, set-up. Eur Spine J 14 (10):920–924

Engel GL (1977) The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science 196(4286):129–136

Waddell G (1987) 1987 Volvo award in clinical sciences. A new clinical model for the treatment of low-back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 12(7):632–644

Nicholas MK, Linton SJ, Watson PJ, Main CJ (2011) Early identification and management of psychological risk factors (“yellow flags”) in patients with low back pain: a reappraisal. Phys Ther 91(5):737–753. doi:10.2522/ptj.20100224

Linton SJ (2000) A review of psychological risk factors in back and neck pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 25(9):1148–1156

Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Katon W, Kroenke K (2003) Depression and pain comorbidity: a literature review. Arch Intern Med 163(20):2433–2445. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.20.2433

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Lowe B (2009) An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics 50(6):613–621. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613

Gureje O, Simon GE, Von Korff M (2001) A cross-national study of the course of persistent pain in primary care. Pain 92(1–2):195–200 (S0304-3959(00)00483-8 [pii])

Leeuw M, Goossens ME, Linton SJ, Crombez G, Boersma K, Vlaeyen JW (2007) The fear-avoidance model of musculoskeletal pain: current state of scientific evidence. J Behav Med 30(1):77–94. doi:10.1007/s10865-006-9085-0

Gerrits MM, van Oppen P, van Marwijk HW, Penninx BW, van der Horst HE (2014) Pain and the onset of depressive and anxiety disorders. Pain 155(1):53–59. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2013.09.005

Genevay S, Marty M, Courvoisier DS, Foltz V, Mahieu G, Demoulin C, Fontana AG, Norberg M, de Goumoens P, Cedraschi C, Rozenberg S (2014) Validity of the French version of the Core Outcome Measures Index for low back pain patients: a prospective cohort study. Eur Spine J 23(10):2097–2104. doi:10.1007/s00586-014-3325-8

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP (1983) The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67(6):361–370

Coste J, Le Parc JM, Berge E, Delecoeuillerie G, Paolaggi JB (1993) French validation of a disability rating scale for the evaluation of low back pain (EIFEL questionnaire). Rev Rhum Ed Fr 60(5):335–341

Marty M, Blotman F, Avouac B, Rozenberg S, Valat JP (1998) Validation of the French version of the Dallas Pain Questionnaire in chronic low back pain patients. Rev Rhum Engl Ed 65(2):126–134

Perneger TV, Combescure C, Courvoisier DS (2010) General population reference values for the French version of the EuroQol EQ-5D health utility instrument. Value Health 13(5):631–635. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4733.2010.00727.x

Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J (1961) An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 4:561–571

Delay J, Pichot P, Lemperiere T, Mirouze R (1963) the Nosology of Depressive States. Relation between Etiology and Semeiology. 2. Results of Beck’s Questionaire. Encephale 52:497–504

Spielberger C, Gorsuch R, Lushene R (1970) Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Palo Alto, California

Bruchon-Schweitzer M, Paulhan I (eds) (1993) French version of the STAY-Y. ECPA, Paris

Tubach F, Ravaud P, Beaton D, Boers M, Bombardier C, Felson DT, van der Heijde D, Wells G, Dougados M (2007) Minimal clinically important improvement and patient acceptable symptom state for subjective outcome measures in rheumatic disorders. J Rheumatol 34(5):1188–1193 (0315162X-34-1188 [pii])

Tubach F, Wells GA, Ravaud P, Dougados M (2005) Minimal clinically important difference, low disease activity state, and patient acceptable symptom state: methodological issues. J Rheumatol 32(10):2025–2029 (0315162X-32-2025 [pii])

Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, van der Windt DA, Knol DL, Dekker J, Bouter LM, de Vet HC (2007) Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol 60(1):34–42

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd edn. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale NJ

Steiner D, Norman G (1995) Health measurement scales: a practical guide to their development and use. Oxford Medical Publications, Oxford

Bland JM, Altman DG (1986) Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1(8476):307–310

Hopkins WG (2000) Measures of reliability in sports medicine and science. Sports medicine 30(1):1–15

Tubach F, Ravaud P, Baron G, Falissard B, Logeart I, Bellamy N, Bombardier C, Felson D, Hochberg M, van der Heijde D, Dougados M (2005) Evaluation of clinically relevant changes in patient reported outcomes in knee and hip osteoarthritis: the minimal clinically important improvement. Ann Rheum Dis 64(1):29–33. doi:10.1136/ard.2004.022905

Moore JE (2010) Chronic low back pain and psychosocial issues. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 21(4):801–815. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2010.06.005

Tlach L, Hampel P (2011) Long-term effects of a cognitive-behavioral training program for the management of depressive symptoms among patients in orthopedic inpatient rehabilitation of chronic low back pain: a 2-year follow-up. Eur Spine J 20(12):2143–2151. doi:10.1007/s00586-011-1810-x

Dickens C, Jayson M, Sutton C, Creed F (2000) The relationship between pain and depression in a trial using paroxetine in sufferers of chronic low back pain. Psychosomatics 41(6):490–499. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.41.6.490

van Tulder MW, Touray T, Furlan AD, Solway S, Bouter LM (2003) Muscle relaxants for nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane collaboration. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 28(17):1978–1992. doi:10.1097/01.BRS.0000090503.38830.AD

Lawlis GF, Cuencas R, Selby D, McCoy CE (1989) The development of the Dallas Pain Questionnaire. An assessment of the impact of spinal pain on behavior. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 14(5):511–516

Kendall N, Linton S, Main C (1997) Guide to assessing psychosocial yellow flags in acute low back pain: risk factors for long-term disability and work loss. Wellington, New Zealand

Melloh M, Elfering A, Salathe CR, Kaser A, Barz T, Roder C, Theis JC (2012) Predictors of sickness absence in patients with a new episode of low back pain in primary care. Ind Health 50(4):288–298 DN/JST.JSTAGE/indhealth/MS1335 [pii]

Wahlman M, Hakkinen A, Dekker J, Marttinen I, Vihtonen K, Neva MH (2014) The prevalence of depressive symptoms before and after surgery and its association with disability in patients undergoing lumbar spinal fusion. Eur Spine J 23(1):129–134. doi:10.1007/s00586-013-2896-0

Murray E, Franche RL, Ibrahim S, Smith P, Carnide N, Cote P, Gibson J, Guzman J, Koehoorn M, Mustard C (2013) Pain-related work interference is a key factor in a worker/workplace model of work absence duration due to musculoskeletal conditions in Canadian nurses. J Occup Rehabil 23(4):585–596. doi:10.1007/s10926-012-9408-7

Hirsch O, Strauch K, Held H, Redaelli M, Chenot JF, Leonhardt C, Keller S, Baum E, Pfingsten M, Hildebrandt J, Basler HD, Kochen MM, Donner-Banzhoff N, Becker A (2014) Low back pain patient subgroups in primary care: pain characteristics, psychosocial determinants and health care utilization. Clin J Pain 30(12):1023–1032. doi:10.1097/AJP.0000000000000080

Melloh M, Elfering A, Kaser A, Salathe CR, Barz T, Aghayev E, Roder C, Theis JC (2013) Depression impacts the course of recovery in patients with acute low-back pain. Behav Med 39(3):80–89. doi:10.1080/08964289.2013.779566

Acknowledgments

We thank all the team from “Nukleus” and, in particular, Mrs V. Gordin and M. Demonnet for their help and logistic support. We wish also to thank members of the Spine section of the French Rheumatology Society for their support in recruiting patients. This study also benefited from an unrestricted grant from Pfizer AG.

Conflict of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cedraschi, C., Marty, M., Courvoisier, D.S. et al. Core Outcome Measure Index for low back patients: do we miss anxiety and depression?. Eur Spine J 25, 265–274 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-015-3935-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-015-3935-9