Abstract

In this article the authors present their on-going research on a generic best-of-breed sustainability management process and toolkit for SMEs, based on an extensive comparative analysis of existing Flemish and Dutch sustainability management tools, literature and consultancy practices. The proposed best-of-breed process and toolkit will enable managers to plan and monitor sustainability implementation, to innovate/optimize their products and processes and also to rethink and innovate the existing business models. To facilitate SME managers to prioritize correctly, the authors define the main topics a toolkit should address. With this research, the authors aim to contribute to the development of literature about sustainability implementation and development in small and medium-sized enterprises in a European setting.

Zusammenfassung

Der Bedarf an Nachhaltigkeitsberatung bei flämischen KMUs ist groß, die Zahlungsbereitschaft jedoch klein. Eine Analyse des Angebots der zahlreichen kostenlosen Programme und Modelle zeigt, dass diese nicht geeignet sind um sowohl strategisch als taktisch zu planen. Dieser Beitrag zeigt, wie ein kostenloser, generischer Management Prozess gestaltet werden kann auf der Basis von Literatur, Praxiserprobung und einer Analyse jener existierenden kostenlosen Programme. Das neue vorgeschlagene generische Modell ermöglicht es KMU-Managern, die Implementierung von Nachhaltigkeitsinitiativen besser zu planen, koordinieren und kontrollieren, ihre Produkte und Prozesse zu verbessern und auch auf strategischer Ebene über Nachhaltigkeit nachzudenken. Das auf PDCA und Projekt Management basierende Modell besteht aus fünf Phasen (Analyse, Steuerung, Spezifizierung, Implementierung, Kontrolle & Rapportierung) wobei die dritte Phase (Spezifizierung) durch ein Dashboard mit sämtlichen Themenbereiche und möglicher operationellen Zielsetzungen erweitert wird.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Problem statement, research questions and methodology

The BASF-Deloitte-Elia-Chair on Sustainability, is a joint project between the University of Antwerp’s Faculty of Applied Economics and Antwerp Management School. SMEs compose one of the strong points of focus for the Chair. Driven by the ambition to present practice-relevant research we look at tangible business impacts, instead of focusing on abstract or ethical constructs. This approach is vital when convincing management of small SMEs to integrate sustainability into their strategy and operations. In 2013, the BASF-Deloitte-Elia Chair on Sustainability started a research project aimed at SMEs. The goal is to identify business relevant CSR-issues across the value chain and to create a CSR policy around them. Essential in this project are the assumptions that:

-

investing in process-efficiency;

-

reducing the ecological footprint of products and services;

-

investing in organizational excellence;

-

strategically rethinking the business model to create sustainable business or to enable shared value creation

leads to

-

a future-proof business model;

-

lesser costs and more revenue;

-

larger internal and external satisfaction.

Multiple organizations and initiatives offer help to Flemish SMEs to adopt at least some aspects of CSR and sustainability in their management practices via tools and/or roadmaps. Partial aspects of CSR and sustainability are already integrated in the quality and health & safety management programs of SMEs. But, backed by our experience with 20 sustainability-projects in Flemish SMEs and CSR market studies in Flanders (Maas 2012; Dockx and Detavernier 2013; Eelen and Truyens 2013), we still notice that there is a strong demand for a holistic, generic and user-friendly management approach for SMEs. Such a process and toolkit should allow managers to plan, implement and test their sustainability initiatives across the value chain. Until now, no real study was carried out to categorize and analyze existing tools and to discover which aspects of CSR and sustainability they focused on and which they neglected. Our research aimed to fill this gap and addressed the following questions:

RQ 1) “Which elements included in the Flemish and Dutch sustainability management tools can be used for the construction of a generic practice- and process-oriented toolkit?”

RQ 2) “Which generic management process model can be based on literature and the best-of-breed characteristics of the analyzed tools?”

RQ3) “Which sustainability domains/topics should a complete management approach address?”

In order to answer these questions we conducted a literature review, carried out a comparative analysis of available sustainability-tools in Belgium and analyzed consultancy approaches. In various stages of the research we also discussed preliminary findings and hypotheses with SME managers.

2 Literature review

2.1 CSR and sustainability

The understanding of CSR and sustainability has converged over the last decades (Montiel 2008). We are well aware of the discussion about CSR and sustainability definitions (e.g. Van Marrewijk 2003; Dahlsrud 2006; Rahman 2011) and assume CSR (focus on current organizational impact) to be a part of sustainability (focus on current and future organizational impact and societal needs). Our approach to CSR and sustainability is strongly determined by the 2011 definition of the European Commission and covers all these aspects and concerns: “the responsibility of enterprises for their impacts on society”. “Respect for applicable legislation, and for collective agreements between social partners, is a prerequisite for meeting that responsibility. To fully meet their corporate social responsibility, enterprises should have in place a process to integrate social, environmental, ethical, human rights and consumer concerns into their business operations and core strategy in close collaboration with their stakeholders, with the aim of: maximizing the creation of shared value for their owners/shareholders and for their other stakeholders and society at large; identifying, preventing and mitigating their possible adverse impacts. The complexity of that process will depend on factors such as the size of the enterprise and the nature of its operations. For most small and medium-sized enterprises, especially microenterprises, the CSR process is likely to remain informal and intuitive. To maximize the creation of shared value, enterprises are encouraged to adopt a long-term, strategic approach to CSR, and to explore the opportunities for developing innovative products, services and business models that contribute to societal wellbeing and lead to higher quality and more productive jobs.” (European Commission 2011, p. 6)

2.2 SMEs and sustainability

Sustainability has obtained a central position in the strategy and operations of larger corporations and organizations for some years now. Legislative initiatives such as the new 2014 European Council Directive concerning disclosure of non-financial and diversity information by large companies and groups (500 + employees) pave the way for even more corporate attention to the subject (European Commission 2014).

Research on the drivers of CSR/sustainability development and its underlying business rationale in SMEs is ample (Williamson and Lynch-Wood 2006; Spence and Rutherfoord 2001; Triguero et al. 2013; Burton and Goldsby 2009; Verboven et al. 2013). Many SMEs still find it difficult to determine the practical relevance of sustainability for their business or to focus on the potential gain or business case instead of the initial cost. Moreover, many SMEs have considerable time and resource constraints that keep them from professionally integrating sustainability and CSR in the value chain. One would be tempted to relate this to the size of the company. Still, research on the relationship between company size and CSR activities does not provide clear evidence to assume that the implementation of CSR is a direct function of company size (Baumann-Pauly et al. 2013; Udayasankar 2008; Smith 2013). Baumann-Pauly et al. claimed that “while firm size does not by definition determine the CSR implementation approach, size implies a range of organizational characteristics, some of which are more, others less advantageous for implementing CSR” (Baumann-Pauly et al.2013, p. 28).

2.3 Sustainability management advice and toolkits in Flanders

Next to the traditional large consultancy firms, some specialized sustainability firms operate on the Flemish market. This type of tailored-fit advice, however, comes at a serious cost, which is a barrier for smaller SMEs. The methods these practitioners use are not “open source” but part of their business capital. Previous studies (Daems and Van Eersel 2013; Eelen and Truyens 2013) analyzed the market for CSR advice in Flanders and compared it to the Netherlands. Both supply and demand side in Flanders are lesser developed and the propensity to pay for advice in Flanders is lower.

Government organizations, NGOs, employer, sector and industry associations and consultancy firms have identified the need for SMEs to adopt at least some aspects of sustainability in their management practices and stressed the necessity of a more systematic approach to sustainability in smaller business entities already. This gave rise to a series of tools and instruments that can measure and steer specific aspects of CSR and sustainability. These are the tools we focus on in our research. It seems that until now there is no real holistic tool for Flemish SMEs that allows them to think strategically and at the same time look at tactics and operations. Some tools are a sort of canvas for management processes whereas others only aim at reporting and yet others are so specific that they can only be applied in certain sectors or industries. Furthermore, there still seems to be a sort of fear of stressing the business effects of CSR and a vagueness in what CSR or sustainability really is about.

2.4 Features of a hypothetical “ideal” tool

The challenge for a generic tool is to address complexity and uniqueness. In the 2013 document “Tips and Tricks for Advisors” (European Commission/Adelphi 2013), the authors offer advice and instructions regarding toolkits and roadmaps for the implementation of CSR in SMEs. The authors also list aspects they believe to be important for a good toolkit (p. 7–10). Although this manual was designed for consultants and coaches, it contains useful advice for our approach which aims at an internal team without (much) intervention of consultants.

The authors summarize the four main aspects of the motivation of SMEs to engage in CSR (European Commission/Adelphi 2013, p. 10):

-

1.

Lead to business benefits—both tangible as intangible;

-

2.

Address personal values;

-

3.

Address institutional factors, i.e. comply with industry, social and legislative expectations;

-

4.

Address stakeholder expectations.

When we look at these aspects we notice that 1 and 2 are internal, 3 and 4 external drivers. These drivers match with the commonly stated fact that CSR is in the interests of companies and society as a whole, as stated in the 2011 EU document on CSR. (European Commission 2011, p. 3)

An extensive tool should therefore cover these four aspects. Still, in terms of deliverables, a good tool should focus especially on the business effects (1). Personal values (2) are a motivational driver and will probably lead to stronger preferences for a specific type of CSR but they can hardly be part of a toolkit. The external drivers (3 and 4) should be considered already in the design phase of the toolkit. A link with GRI4 or lesser complex reporting is necessary. A stakeholder dialogue can identify specific priorities which could lead to a focus on specific locations in the value chain.

With regard to the development of a process or roadmap the Adelphi manual identifies four important elements at start (European Commission/Adelphi 2013, p. 13):

-

1.

“Raise awareness of ways in which the company is already meeting its social responsibility.”

-

2.

“Identify small actions in areas such as human resources, supply chain, community, or environment that can lead to “quick wins” and foster employee motivation and engagement.”

-

3.

“Align CSR measures with the core objectives and competencies of the enterprise—mainstream it across all areas of business operations, embed it into day-to-day business culture and use the CSR strategy to increase competitiveness.”

-

4.

“Set more ambitious targets, such as taking a life cycle approach.”

The implementation phase of the roadmap is to our opinion the most important phase. Again the Adelphi manual offers some ideas and it identifies ten aspects which we summarize (European Commission/Adelphi 2013, p. 14–17):

-

1.

Internal CSR team

-

2.

Self-assessment and as-is

-

3.

Benchmarking

-

4.

Building a business case

-

5.

Asking about personal values

-

6.

Identify stakeholders

-

7.

Identify priority areas

-

8.

Support with implementation by providing tools

-

9.

Communicating CSR activities

-

10.

Measuring and assessing progress

We do doubt, however, the logical order in this list and want to stress that the only real “action” is taking place in 8. It is here that results are being made. We believe that the focus should be much more directed to this point. Our general critique is that too much attention is being paid to non-business-related factors. In a context with limited resources (time and money) one should immediately come to the point.

Though they are different concepts, there is quite some resemblance between CSR and quality management. Moreover, they can strengthen each other. Whereas CSR remains vague and somehow focusses too strong on the moral side and not enough on operations and tactics, QM is maybe too focused on the optimization of specific processes with the risk of losing track of the bigger picture and the “why it matters” (Verboven et al. 2013).

Third generation quality management (3QM) identifies this problem and combines the holistic vison of sustainability and value creation with tangible deliverables in processes. A combination of CSR and 3QM in a roadmap or toolkit could offer the solution for a sustainable optimization toolkit (Jonker and Reichling 2013, p. 10). To our opinion, a tool that would be capable of starting the CSR transformation both top down (systematic policy) as bottom up (process QM) would be the ideal tool to motivate SME managers with immediate tangible results. The CSR transformation would then take place along structural lines of processes throughout the entire value chain.

Our literature review and the findings from our interaction with SME managers led us to the statement of the following characteristics that a good tool/roadmap should offer:

-

Focus on feasible and tangible business results;

-

Offer clear definitions, concepts and how-to’s;

-

Be part of a trajectory/roadmap (Hohnen 2007);

-

Allow holistic approach with possible detailed focus;

-

CSR transformation from both top down (systematic policy) as bottom up (process QM) and delivers systematically tangible results throughout entire value chain;

-

Implement PDCA for policy, PMO for monitoring and BSC for evaluation;

-

Look for new ideas to make operations green from the start (strategic part).

3 Discussion

3.1 RQ1: Analysis of existing sustainability management tools and roadmaps

RQ1: “Which elements included in the Flemish and Dutch sustainability management tools can be used for the construction of a generic practice- and process-oriented toolkit?”

To answer this question, we identified general and specific features of the sustainability management tools. We characterized every tool by its level of detail, the sustainability themes it addresses and the phase in the sustainability implementation process it supports. Classification was necessary to reveal essential features and possible gaps or limitations of existing tools. Figure 1 shows our classification of the analyzed tools according to their level of detail and phase of the sustainability management process they support.

The level of detail (low, average, high) is closely linked to the objectives of the tools. In general, tools with a low level of detail are aimed at raising sustainability awareness and initiating certain topics. Tools with an average level of detail mostly cover a wide range of sustainability themes, however only superficially. Highly detailed tools aim to offer very specific support. Therefore we could state that the level of detail is often related to (the number of) sustainability themes a tool addresses. For a thematic integration we refer to RQ3.

The classification based on the sustainability management process phases is preliminary and a more detailed look into this is given in RQ2.

A quick scan, an as-is description or a clear benchmark to e.g. ISO 26000 is crucial at the start of every CSR and sustainability project. Still it remains somewhat unclear to us, how exactly the discussed initiation tools and quick scans in Flanders succeed at really convincing SMEs of the business effects of CSR. They seem to aim more at the moral side of arguments (CSR is good for society, so do so) or put the level of concordance with ISO26000 as the ideal state instead of focusing on business effects first and societal value secondly. We fear that such an approach is at risk of losing at least some attention of SME managers.

Furthermore, the available tools wave tools fall short of offering an integrated approach and roadmap for CSR policy implementation across the value chain. In fact, even the more extensive coordinating tools still do not cover all potential aspects and are not ambitious enough to our opinion. This statement was backed by the experience from our corporate projects.

Only the action & inspiration and combination tools (both coordinating and specific) succeed to some extent at making both a business case and a societal case for CSR. The lack of systemic approach and the rather dogmatic focus on ISO26000, however, hinders the applicability for SMEs. One of the obvious reasons for this is the fact that the elaboration of the coordinating tools into tactics is typically a thing for specialized consulting which cannot be an open source free model. Initiation and coordinating tools act in that aspect as teasers or freemium for a closed source level (specific tools).

Our classification reveals a wide diversity among the investigated tools, which hinders comparison. The suitability of each tool depends strongly on the SME’s intentions. However, this is not always clearly stated as tools sometimes claim to be an ‘all-in-one’ solution when they lack detail or only cover one phase of the sustainability management process.

Subsequently we combined the features of a hypothetical “ideal” tool (see 2.4) with the characteristics of the analyzed tools. These characteristics can be classified as ‘elements’ that need to be used for the construction of the generic practice- and process-oriented (best-of-breed) toolkit.

3.2 RQ2: The generic sustainability management process

RQ2: “Which generic sustainability management process model can be based on literature and the best-of-breed characteristics of the analyzed tools?”

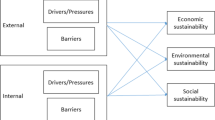

Best-of-breed characteristic 1 (Fig. 2) states that a separation between the description of the sustainability management process and the components, that could be integrated in the toolkit and used to support this process, should be made. We therefore start with the formulation of a hypothetically ideal process.

Although Flemish SMEs recognize the importance of sustainability and CSR, many of them implement sustainability initiatives ad hoc (Maas and Reniers 2013). Several authors emphasize that a good sustainability strategy and management process will enhance competitive advantage (Maas and Reniers 2013; Rangan et al. 2015). However, the specific nature of SMEs requires a steering and inspiring process, rather than a too prescriptive or formal one (European Commission/Adelphi 2013). Hence the ‘ideal’ toolkit should at least offer this process and explain possible uses to SMEs. The process could be executed cyclical, or only one (or more) phase(s) could be partially used, dependent on the SME’s needs. In case of cyclical use, the execution of some phases could be restricted in the 2nd, 3rd … cycle. The number of cycles will be finite when sustainability initiatives are limited to efficiency improvements and strategic innovation does not take place. Overlap of phases of the process is possible, especially when projects in different sustainability domains are executed simultaneously.

In our corpus of investigated tools we found but rarely a reference to a sustainability management process. Consequently, we looked into other theoretical models and approaches, mainly focused on SMEs, such as the Sus5-Framework from Maas and Reniers (2013), the business opportunity model of Jenkins (2004) and the CSR implementation framework of Hohnen (2007) for inspiration. The synthesis of the processes in consulted tools, roadmaps and models results in the following proposal for a sustainability management process (Fig. 3).

Our proposed generic sustainability management process consists of five phases. During each of the stages stakeholder engagement is advised. The practical implications of this process depend on the SME’s business context, nevertheless the ‘ideal’ toolkit could offer support for each phase.

Analyse

The first phase covers the analysis of the internal organization, which includes collecting general information about the SME (culture, annual reports etc.) and about the past and current sustainability activities; and the external context with focus on directives and laws, stakeholder analysis, sustainability benchmarking and industry trends. Analysis could be based on information from questionnaires, in-depth interviews and/or the SME’s own research.

The best-of-breed toolkit could support the analyse phase by providing detailed self-assessment questionnaires, concerning the different themes of sustainability. The questionnaires should examine the sustainability governance, topics, implementation, evaluation and responsibilities. This is congruent with the analyse tools in Fig. 1.

Decide on direction (steering)

‘Decide on direction’ ensures the establishment of a sustainability vision and values. Furthermore, a decision structure for sustainability initiatives should be created and thereafter themes could be chosen, based on phase 1. Phase 2, decide on direction, is necessary to ensure a well-directed sustainability management, rather than ad hoc initiatives.

The ‘ideal’ toolkit helps to make decisions about the strategic direction by generating good outputs (see characteristic 4, Fig. 2) based on the questionnaires from the analyse-phase. Futhermore, an overview of sustainability themes for SMEs should be provided. A proposal for this overview is given in 3.3. Phase 2 is partially consistent with the action & inspiration tools in Fig. 1.

Make specific

During this phase, the outlines chosen in phase 2 will be made concrete by proposing sustainability activities, prioritizing activities and providing KPIs. Prioritization of activities should be based on:

-

Necessity for the SME (based on the results of phase 1);

-

A balance between short term and long term initiatives and the realization of quick wins to keep employees motivated;

-

The SME’s impact on the subject;

-

The business case and available budget and resources.

In support of the execution of this phase, the best-of-breed toolkit should provide examples of cases and an overview of possible non-strategic and strategic activities to ameliorate the SME’s sustainability. Key performance indicators could be included too. For each theme, activities and KPIs have been found in the investigated tools and they were listed in extensive libraries. Due to their extent, they are not included in this article. Phase 3 has similarities with the action & inspiration (and measurement) tools in Fig. 1.

Implement

Implementation necessitates to assign activities and their execution to employers. The undertaken actions should be anchored in daily operations. In the Flemish and Dutch sustainability management tools there was no element of support found for this phase. Project and change management guidelines offer, however, ample information on implementation trajectories.

Control & report

This phase will examine if goals were achieved and if evolution over time was positive. This should be based on the determined KPIs and internal feedback. ‘Control & report’ could be executed internally or externally, which enhances credibility and transparence. A component that simplifies data registration and generates clear outputs could be integrated into the best-of-breed toolkit. The investigated tools did not elaborate on reporting. We proposed a report based on project management and the Balanced Scorecard Method. The measurement tools in Fig. 1 are most similar to the necessary features in this phase.

Stakeholder management

‘Stakeholder management’ aims to improve stakeholder commitment and to generate support for sustainability activities. The realization of this phase is strongly context-dependent. In the ‘ideal’ toolkit, examples of initiatives improving commitment of stakeholders towards the sustainability politics for every stage in the process could be mentioned.

3.3 RQ3: List of relevant topics

RQ3: “Which sustainability domains/topics should a complete management approach address?”

The investigated tools revealed three types of thematic classifications: classifications based on Elkington’s Triple Bottom Line (tools 1, 4, 5, 6, 9 and 11), based on ISO 26000 (tools 2, 3, 7, 10) and based on an integration of those classifications (tool 8). The range of covered sustainability subjects is extensive, however, the absence of themes and initiatives facilitating true business model innovation and strategic excellence is noteworthy and in contrast to academic literature.

In literature, a strategic approach is often mentioned, however definitions of strategic excellence, strategic transformation or business model innovation are mostly vague when sustainability is concerned. For our research, we used the definition of Bocken et al. (2014, p. 44): “Innovations that create significant positive and/or significantly reduced negative impacts for the environment and/or society, through changes in the way the organisation and its value-network create, deliver value and capture value (i.e. create economic value) or change their value propositions.” This definition results in a grey area for several sustainability themes and activities, because their level of strategicness depends on actions realised in the past by the SME.

To compensate for the lack of themes facilitating true strategic advance in the existing tools, in our classification, themes were added, based on academic literature and were classified (in the vertical dimension) as contributing to product, operational, organizational or strategic excellence. The focus of ‘product excellence’ is on the design and use phase of the product lifecycle, whereas ‘operational excellence’ focusses on production and distribution. ‘Organizational excellence’ concerns themes such as governance and HRM whereas ‘strategic excellence’ addresses, as mentioned before, true business model innovation. The horizontal dimension differentiates between topics that are internal, resources related (tangible and intangible), have an impact on the environment or, again, are related to strategical excellence. The sustainability topics/domains (1–20) are the result of an integration of the themes addressed by the 15 investigated tools. The absence of a financial dimension is justified by the large overlap with the included domains.

Figure 4 shows the proposed categorization and domains in which sustainability issues are to be situated. The given overview is concise, but comprehensive and a gateway to a more in-depth elaboration. For each of the domains we formulated extensive catalogues of possible tools, actions and matching KPIs. As a consequence, the given model supports several phases of the sustainability management process as well as various uses, ranging from the first choice of sustainability topics to the selection of concrete actions for the SME.

4 Conclusion

Based on market studies of CSR in Flanders we found that there is a demand for a holistic, generic and user-friendly management approach that allows SME managers to plan, implement and test their sustainability initiatives across the value chain. The construction of such a generic model was the central goal of this paper. We discussed the features of a hypothetically “ideal” process or CSR-tool in literature and combined these features with our own research findings. We identified 7 characteristics that are crucial to include in a generic model. Subsequently, we presented a classification of 15 CSR-tools and combined this with the findings of literature. This enabled us to list 5 best-of-breed-characteristics that were further elaborated.

We combined the findings of our literature review with results of the analysis of existing Flemish and Dutch tools for sustainability and formulated a five step cyclical process model that can be used by every SME. This generic sustainability management process model is a combination of PDCA and project management and is basically designed for self-steering CSR teams. The model consists of five stages (analyse, steer, make specific, implement, control & report) and allows for continuous stakeholder engagement.

Finally we focused in detail on the third phase of our model (make specific) and presented an overview of sustainability domains that can be covered by an SME. These domains and their categorization is based on both literature as practice. We presented this in the form of a dashboard-like toolkit with 20 domains or topics and 9 business model innovators. In the scope of this paper we could not zoom in on the content of each of those topics. We did however elaborate this extensively to offer tangible business impacts and are currently testing the tool with selected Flemish companies. In a further phase of this ongoing research the proposed tool will be integrated into a project management interface.

References

Baumann-Pauly D, Wickert C, Spence LJ, Scherer AG (2013) Organizing corporate social responsibility in small and large firms: size matters. J Bus Eth 115(4):693–705

Bocken N, Short S, Rana P, Evans S (2014) A literature and practice review to develop sustainable business model archetypes. J Clean Prod (65):42–56

Brammer S, Hoejmose S, Marchant K (2012) Environmental management in SMEs in the UK: practices, pressures and perceived benefits. Bus Strategy Environ 21(7):423–434

Burton B, Goldsby M (2009) Corporate social responsibility orientation, goals and behavior: a study of small business owners. Bus Soc 48(1):88–104

Daems K, Van Eersel L (2013) MVO- en Duurzaamheidsadvies in Vlaanderen en Nederland. Vergelijking van de markt (I). Masterproef Universiteit Antwerpen, Faculteit TEW

Dahlsrud A (2006) How corporate social responsibility is defined: an analysis of 37 definitions. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 15(1):1–13

Docxk D, Detavernier M (2013) MVO-management in KMO’s. Op weg naar een rendabele en duurzame implementatie. Masterproef Universiteit Antwerpen, Faculteit TEW

Eelen Y, Truyens L (2013) MVO- en Duurzaamheidsadvies in Vlaanderen en Nederland. Vergelijking van de markt (II). Masterproef Universiteit Antwerpen, Faculteit TEW

European Commission (2011) A renewed EU strategy 2011-14 for Corporate Social Responsibility. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2011:0681:FIN:en:PDF

European Commission (2014) Directive 2014/95/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2014 amending Directive 2013/34/EU as regards disclosure of non-financial and diversity information by certain large undertakings and groups Text with EEA relevance. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32014L0095)

European Commission/Adelphi (2013) Tips and Tricks for Advisors. Corporate Social Responsibility and Small & Medium Enterprises (SMEs). https://www.google.be/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0CCAQFjAAahUKEwj18uW9ssvHAhUKvRoKHfN6C9A&url=http%3A%2F%2Fec.europa.eu%2FDocsRoom%2Fdocuments%2F10368%2Fattachments%2F1%2Ftranslations%2Fen%2Frenditions%2Fpdf&ei=fCDgVfXENYr6avP1rYAN&usg=AFQjCNFxHQZDCeOx6kt5_lt9Fvd9wEi8pA

Hohnen P (2007) Corporate Social Responsibility. An implementation guide for businesses. http://www.iisd.org/pdf/2007/csr_guide.pdf

Jenkins H (2004) A critique of conventional CSR theory: an SME perspective. J General Manag 29(4):55–75

Rangan K, Chase L, Karim S (2015). The truth about CSR. Harvard Business Review, 93(1/2): 41-49

Reichling A, Jonker J (eds) (2013) Derde generatie kwaliteitsmanagement: vertrekken, zoeken, verbreden. Kluwer, Mechelen

Maas S (2012) Ontwikkeling van een kader voor een innovatief beheersysteem voor CSR: theoretische ontwikkeling en kwalitatieve evaluatie in Vlaanderen. Masterproef Universiteit Antwerpen, Faculteit TEW

Maas S, Reniers G (2013) Development of a CSR model for practice: connecting five inherent areas of sustainable business. J Clean Prod 64(1):104–114. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.07.039

Montiel I (2008) Corporate social responsibility and corporate sustainability: separate pasts, common futures. Organ Envron 21(3):245–269. doi:10.1177/1086026608321329

Rahman S (2011) Evaluation of definitions: ten dimensions of corporate social responsibility. World Rev Bus Res 1(1):166–176

Smith N (2013) When it comes to CSR, Size Matters. http://www.forbes.com/sites/insead/2013/08/14/when-it-comes-to-csr-size-matters/

Spence LJ, Rutherfoord R (2001) Social responsibility, profit maximisation and the small firm owner-manager. Small Bus Enterp Dev 8(2):126–139

Triguero A, Moreno-Mondéjar L, Davia MA (2013) Drivers of different types of eco-innovation in European SMEs. Ecol Econ 92:25–33 (August)

Udaysankar K (2008) Corporate social responsibility and firm size. J Bus Ethics 83(2):167–175

Van Marrewijk M (2003) Concepts and definitions of CSR and corporate sustainability: between agency and communion. J Bus Eth 44(2–3):95–105

Verboven H, Van Liedekerke L, Libert L (2013) Maatschappelijk verantwoord ondernemen in het midden- en kleinbedrijf (MKB). In: Reichling A, Jonker J (eds) Derde generatie kwaliteitsmanagement: vertrekken, zoeken, verbreden. Kluwer, Mechelen, pp 189–205

Williamson D, Lynch-Wood G (2006) Drivers of environmental behaviour in manufacturing SMEs and implications for CSR. J Bus Eth 6(3):317–330

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Verboven, H., Vanherck, L. Sustainability as a management process for SMEs. uwf 23, 241–249 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00550-015-0367-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00550-015-0367-2