Abstract

Background

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is characterized by progressive inflammation and necrosis of hepatocytes and eventually leads to a variety of phenotypes, including acute liver dysfunction, chronic progressive liver disease, and fulminant hepatic failure. Although the precise mechanisms of AIH are unknown, environmental factors may trigger disease onset in genetically predisposed individuals. Patients with the recently established entity of AIH with acute presentation often display atypical clinical features that mimic those of acute hepatitis forms even though AIH is categorized as a chronic liver disease. The aim of this study was to identify the precise clinical features of AIH with acute presentation.

Methods

Eighty-six AIH patients with acute presentation were retrospectively enrolled from facilities across Japan and analyzed for clinical features, histopathological findings, and disease outcomes.

Results

Seventy-five patients were female and 11 were male. Patient age ranged from adolescent to over 80 years old, with a median age of 55 years. Median alanine transaminase (ALT) was 776 U/L and median immunoglobulin G (IgG) was 1671 mg/dL. There were no significant differences between genders in terms of ALT (P = 0.27) or IgG (P = 0.51). The number of patients without and with histopathological fibrosis was 29 and 57, respectively. The patients with fibrosis were significantly older than those without (P = 0.015), but no other differences in clinical or histopathological findings were observed. Moreover, antinuclear antibody (ANA)-positive (defined as × 40, N = 63) and -negative (N = 23) patients showed no significant differences in clinical or histopathological findings or disease outcomes. Twenty-five patients experienced disease relapse and two patients died during the study period. ALP ≥ 500 U/L [odds ratio (OR) 3.20; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.12–9.10; P < 0.030] and GGT ≥ 200 U/L (OR 2.98; 95% CI 1.01–8.77; P = 0.047) were identified as independent risk factors of disease relapse.

Conclusions

AIH with acute presentation is a newly recognized disease entity for which diagnostic hallmarks, such as ALT, fibrosis, and ANA, are needed. Further investigation is also required on the mechanisms of this disorder. Clinicians should be mindful of disease relapse during patient care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a chronic liver disease characterized by immunologic and autoimmunologic features, generally including the presence of circulating autoantibodies and high levels of immunoglobulin G (IgG) [1]. Although autoantibodies are present in the vast majority of patients with AIH, there is little evidence supporting their involvement in AIH pathogenesis or predictive ability of histologic severity or treatment response [2]. Most cases of AIH respond to anti-inflammatory or immunosuppressive therapy. However, some show rapid progression to fulminant hepatic failure, cirrhosis, or complicating hepatocellular carcinoma over time. The precise cause of AIH remains unknown, but one theory is that environmental factors can trigger disease onset in genetically predisposed individuals. In support of this hypothesis, human leukocyte antigen (HLA) loci displayed the highest susceptibility or protectivity to AIH across ethnicities [3,4,5], along with several genes on non-HLA loci [6,7,8]. Moreover, a recent genome-wide association study identified variants of SH2B3 on chromosome 12 [9] and CARD 10 on chromosome 22 in addition to other HLA regions [9].

The incidence of AIH has been estimated as 1.1 per 100,000 individuals in the Netherlands [10], 1.68 in Denmark [11], and 1.52 in Japan [12], with a prevalence of 18.3, 23.9, and 15.0, respectively. The clinical manifestations of AIH patients are diverse and range from asymptomatic to fulminant hepatic failure. There have recently been rare, but remarkable, AIH cases with acute presentation [13, 14] since a first report in 1984 [15]. The incidence of AIH with acute presentation has increased over the last 2 decades [16]. As patients with AIH are becoming older while serum IgG levels are decreasing in Japan [16], it appears that atypical cases of AIH are expanding and the disease is more diverse than expected. In the diagnosis of AIH, guidelines from the European Association for the Study of the Liver [17] and the Japan Society of Hepatology [18] require liver biopsy as part of the evaluation. Regarding the histopathological features of AIH with acute presentation, we recently reported that the presence of prominent lobular and perivenular necroinflammatory activity, pigmented macrophages, and cobblestone appearance of hepatocytes were useful for diagnosis in addition to the classic AIH features of plasma cell infiltration and emperipolesis [19]. However, as the clinical features of AIH with acute presentation have not been conclusively elucidated, the present study examined the clinical characteristics of this disorder.

Patients and methods

The Japan Autoimmune Hepatitis Study Group (JAIHG) conducted this multicenter retrospective survey among eight hospitals (Shinshu Ueda Medical Center, Fukushima Medical University Hospital, Ehime University Hospital, Jikei University Hospital, Okayama University Hospital, Teine Keijinkai Hospital, Chiba University Hospital, and Kurume University Hospital). Eighty-seven patients who were diagnosed as having AIH with acute presentation of the acute hepatitis phase after ruling out AIH of the acute exacerbation phase by liver specialists between 2005 and 2014 were initially registered in this study. One subject exhibited histological disease progression with fibrosis stage 3 and was therefore excluded. Ultimately, a total of 86 patients having AIH with acute presentation were analyzed. The diagnosis of AIH with acute presentation was based on criteria from the International AIH Group (IAIHG) (1999) [20] as well as guidelines from the Japan Society of Hepatology [18], with scoring for definite or probable AIH and/or empirical judgements by experienced hepatologists on the basis of combined clinical, laboratory, serological, and histological data, as reported previously [19].

No patient had a history of organ transplantation or concurrent use of immunomodulatory drugs or corticosteroids, and none were coinfected with the hepatitis C virus (HCV) confirmed with the HCV antibody, hepatitis B virus confirmed with the HBs antigen, or human immunodeficiency virus type 1 confirmed with the HIV antibody. No subject exhibited evidence of other liver diseases, such as alcoholic liver disease or non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

This study was reviewed and approved by the head of the Institutional Review Board of Fukushima Medical University School of Medicine, Fukushima, Japan (Approval number: 2099) and the ethics committees of the other participating institutions. Written informed consent was obtained from all participating subjects. This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

Laboratory testing

Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (upper limit of normal: 330 U/L), IgG (upper limit of normal: 1700 mg/dL) and other relevant biochemical and serological evaluations were performed using standard methods at the time of liver biopsy at respective institutions.

Histological evaluation

Liver biopsies were performed on all patients and formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded specimens were prepared and used for subsequent histopathological studies. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and connective tissue staining, including Masson’s trichrome and reticulin stainings. All liver biopsy samples were independently evaluated by five experienced pathologists who were blinded to clinical data by means of identical histological scoring sheets covering several parameters that included fibrosis, central zone necrosis, perivenular necroinflammatory activity, lobular necrosis/inflammation, cobblestone appearance, plasma cell infiltration, and emperipolesis, as reported previously [19].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis and data visualization were carried out using StatFlex version 6.0 (Artech Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) and IBM SPSS Statistics version 23.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL) software. Data are presented as the median ± interquartile range for continuous variables. Linear data were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. Groups were compared using the Chi-square test for categorical variables. This model was checked by regression diagnostic plots to verify normality, linearity of the data, and constant variance. Stepwise logistic regression analysis with a forward approach was performed to identify independent factors associated with disease relapse after continuous variables were separated into two categorical variables by the nearest clinically applicable value to the cutoff, being considered as the optimal cutoff value for clinical convenience. All statistical tests were two-sided and evaluated at the 0.05 level of significance.

Results

Baseline clinical characteristics

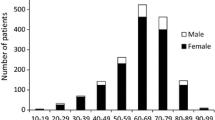

The baseline clinical characteristics in this study are summarized in Table 1. Of the 86 enrolled patients, 75 were female and 11 were male. Median age was 55 years and was distributed from adolescence to over 80 years (Fig. 1a). Median ALT and IgG levels were 776 U/L and 1671 mg/dL, respectively, and were comparable between genders (P = 0.27 and P = 0.51) (Fig. 2a, b). Twenty-three patients (27%) were antinuclear antibody (ANA)-negative (Fig. 1b). Sixty-three patients (73%) were ANA-positive (× 40) at diagnosis, with similar rates between men and women (Fig. 2c). The median duration between the onset of AIH with acute presentation, which was defined as when clinicians predicted based on medical interview and clinical findings, and liver biopsy was 21 days. Based on histological findings, the number of patients with fibrosis stage 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 was 29, 38, 19, 0, and 0, respectively. One patient succumbed to lung cancer and the other did to disease-related death. We next analyzed several parameters to elucidate the clinical features of AIH with acute presentation.

a ALT levels in all, female, and male AIH patients with acute presentation. No significant differences were found. b IgG levels in all, female, and male AIH patients with acute presentation. Dotted line indicates the upper normal limit of IgG level. No significant differences were found. c ANA positivity in all, female, and male AIH patients with acute presentation. No significant differences were found. ALT alanine aminotransferase, IgG immunoglobulin G, ANA antinuclear antibody, N.S. not significant

Comparisons according fibrosis 0 and fibrosis 1–2 stages

Although all patients met the criteria of AIH with acute presentation, 29 (34%) showed no fibrosis and 57 (66%) exhibited early or significant fibrosis. The median age of patients with fibrosis was significantly higher than that patients without (P = 0.015). Moreover, the median duration between disease onset and liver biopsy was markedly longer in the F1-2 group (29 days) than in the F0 group (15 days) (P = 0.052). There were no significant differences in laboratory data, pathological findings, or disease outcomes between the groups (Table 2).

Comparisons according to IgG level

Median IgG level was 1671 mg/dL, indicating that more than half of patients had IgG levels below the upper limit of normal (1700 mg/dL). After stratification according to this limit, the higher IgG group was significantly older than the lower IgG group (Table 3). Anti-smooth muscle antibody (ASMA) positivity was significantly higher in the higher IgG group (P = 0.005) along with IAIHG and simplified scores (P = 0.002 and P < 0.001). No other biochemical parameters or histopathological findings differed significantly between the groups.

Comparisons according to ANA status

Overall, 73% of patients were ANA-positive, defined as ANA ≥ × 40. The ANA-positive group showed significantly higher IgG levels than did the ANA-negative group (P < 0.001) (Table 4). Both IAIHG and simplified scores were significantly higher in the ANA-positive group (P = 0.004 and P < 0.001), although other biochemical parameters and histopathological findings were comparable between the groups.

Treatment

The vast majority of patients with AIH acute presentation were initially treated with prednisolone at an oral dosage of 20-50 mg/day that was gradually tapered after remission.

Clinical outcomes of AIH with acute presentation

Overall, 25 patients (30%) experienced AIH relapse (Fig. 3). The median levels of gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) in the disease relapse group were significantly higher than those in the disease non-relapse group (P = 0.002 and P < 0.001, respectively) (Table 5). No other biochemical parameters or histopathological findings differed remarkably between the groups. A stepwise logistic regression model to determine independent risk factors associated with disease relapse showed that ALP ≥ 500 U/L [nearly 1.5 times the upper limit of normal; odds ratio (OR) 3.20; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.12–9.10; P < 0.030) and GGT ≥ 200 U/L (nearly 4 times the upper limit of normal; OR 2.98; 95% CI 1.01–8.77; P = 0.047) were independent risk factors of disease relapse in AIH with acute presentation after adjustment by age and gender.

One patient ultimately died of lung cancer and one patient succumbed to disease-related death due to unresponsiveness to immune-mediated therapy.

Discussion

This study revealed the following clinical features of AIH with acute presentation: (1) afflicted patients showed elevated levels of ALT, which was compatible with acute hepatitis, while more than half displayed IgG levels lower than the upper limit of normal, unlike AIH with chronic hepatitis; (2) less than half of patients showed no fibrosis, with the remainder exhibiting histologically proven early or significant fibrosis stages; (3) a quarter of patients showed ANA negativity, which is a reminder for clinicians to consider AIH with acute presentation even when patients are ANA-negative; and (4) GGT and ALP were independent risk factors of disease relapse in AIH with acute presentation.

As AIH with acute presentation exhibits higher ALT levels than does chronic hepatitis [16, 21, 22], the diagnosis of acute hepatitis can be easily made in the clinical setting. Moreover, AIH patients with chronic hepatitis typically show high levels of IgG, which can help clinicians with diagnosis; indeed, IgG is included in both IAIHG scoring [20] and the simplified criteria for diagnosing AIH [23]. If scoring systems are relied on, however, there is a risk of underestimating the number of AIH patients with acute presentation. We therefore examined for the clinical characteristics of AIH with acute hepatitis in terms of IgG level but uncovered no significant differences apart from age, ASMA positivity, and the frequency of complicating autoimmune diseases. Moreover, no significant differences between definite and probable AIH groups were found in terms of clinical or histological features. These findings indicated that our cohort was uniform and hence the diagnosis of AIH with acute presentation is challenging. It can also be stated that diagnostic hallmarks for AIH with acute presentation are urgently needed in the clinical setting because treatment strategies differ among types of acute hepatitis, such as AIH patients better responding to corticosteroids.

Centrilobular necrosis without portal inflammation is a particular histopathological finding in AIH with acute presentation [13]. However, it was also reported that the disorder was associated with a variety of histological changes, and that lobular necrosis/inflammation, particularly centrilobular necrosis, plasma cell infiltration, emperipolesis, and pigmented macrophages, were common [19]. Specifically, emperipolesis and rosette formation appear superior to interface hepatitis and plasma cell-rich infiltration as histological predictors of adult AIH with chronic hepatitis [24]. The present study demonstrated no significant differences between patients with and without fibrosis in terms of laboratory findings, histopathological findings, or disease outcomes, including AIH relapse. Although the median duration between disease onset and liver biopsy was markedly longer in the F1-2 group (29 days) than in the F0 group (15 days) (P = 0.052), we were unable to objectively ascertain fibrosis progression rate. However, all cases of clinically diagnosed AIH with acute presentation were confirmed as having fibrosis stage 0, 1, or 2 except for one subsequently excluded patient with stage 3. Since there were no cases of AIH with acute presentation with severe fibrosis, we surmised a predominance of AIH with chronic hepatitis in this group.

ANAs are the most common circulating autoantibodies in AIH and are serologic hallmarks for systemic and organ-specific autoimmune diseases. ANAs are not believed to be involved in AIH pathogenesis and are not predictive of histologic severity or treatment response [2], but are included in both IAIHG scoring [20] and the simplified criteria for AIH diagnosis [23]. As a quarter of patients in this study were ANA-negative, we looked for clinical differences between ANA-negative and -positive groups and observed that IgG level and the frequency of complications with other autoimmune diseases were significantly higher in the ANA-positive group. Further study is required to clarify this intriguing significance of ANA positivity with AIH with acute presentation. Taken together, our findings indicated that ANA, IgG, and complicating autoimmune diseases may be hallmarks of AIH with acute presentation as well as AIH with chronic hepatitis. It was noteworthy that 13% of patients were positive for anti-mitochondrial antibody (AMA), which is a specific and sensitive marker for primary biliary cholangitis (PBC). This was consistent with a previous study revealing an association of AMA positivity with AIH/PBC overlap syndrome [25], wherein no AMA-positive AIH patients progressed to PBC over long-term follow-up. Clarification of the clinical significance of AMA positivity in AIH patients with acute presentation is needed.

Overall, 26 of 86 patients (30%) experienced disease relapse in this study, which was statistically comparable to the incidence in a previous study of 48 of 203 (24%) AIH patients in the chronic phase (P = 0.241) [26], indicating that disease relapse should be always considered both in AIH with acute presentation and AIH in the chronic phase. Comparisons of clinical markers between relapse and non-relapse groups identified two independent risk factors associated with disease relapse. Since relapse was reportedly associated with certain human leukocyte antigen (HLA) types in chronic phase AIH, including HLA-A1, HLA-B8, and HLA-DR3 [27], HLA typing might help uncover additional risk factors associated with disease relapse in AIH with acute presentation as well. Higher gamma globulin levels can also predict relapse after initial treatment [28], but there were no remarkable differences in IgG in this study. Rather, GGT and ALP were independent risk factors of disease relapse in AIH with acute presentation and might assist in disease treatment.

The present study has several limitations. Although multicenter, it was retrospective in nature and of a limited sample size due to our selection of only histopathologically proven cases. Liver biopsy for evaluating the degree of liver fibrosis was prone to sampling error. Some cases exhibited disease relapse. A longitudinal investigation of AIH patients with acute presentation is warranted as well. The environmental factors associated with disease onset according to prior studies on AIH pathogenesis should also be addressed by gathering detailed information in a larger cohort [29].

Conclusions

AIH with acute presentation is a newly recognized disease entity with apparent associations with ALT, fibrosis, ANA, and other clinical characteristics. Clinicians should be mindful of disease relapse, especially with patients exhibiting the above risk factors. Further studies are needed to clarify the diagnostic hallmarks and mechanisms of AIH with acute presentation.

References

Krawitt EL. Autoimmune hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(1):54–66.

Mehendiratta V, Mitroo P, Bombonati A, et al. Serologic markers do not predict histologic severity or response to treatment in patients with autoimmune hepatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(1):98–103.

Seki T, Kiyosawa K, Ota M, et al. Association of primary biliary cirrhosis with human leukocyte antigen DPB1*0501 in Japanese patients. Hepatology. 1993;18(1):73–8.

Yoshizawa K, Ota M, Katsuyama Y, et al. Genetic analysis of the HLA region of Japanese patients with type 1 autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2005;42(4):578–84.

Yoshizawa K, Umemura T, Ota M. Genetic background of autoimmune hepatitis in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46(Suppl 1):42–7.

Umemura T, Ota M, Yoshizawa K, et al. Association of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 gene polymorphisms with type 1 autoimmune hepatitis in Japanese. Hepatol Res. 2008;38(7):689–95.

Yokosawa S, Yoshizawa K, Ota M, et al. A genomewide DNA microsatellite association study of Japanese patients with autoimmune hepatitis type 1. Hepatology. 2007;45(2):384–90.

Umemura T, Joshita S, Hamano H, et al. Association of autoimmune hepatitis with Src homology 2 adaptor protein 3 gene polymorphisms in Japanese patients. J Hum Genet. 2017;62(11):963–7.

de Boer YS, van Gerven NM, Zwiers A, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies variants associated with autoimmune hepatitis type 1. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(2):443–52.

van Gerven NM, Verwer BJ, Witte BI, et al. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of autoimmune hepatitis in the Netherlands. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2014;49(10):1245–54.

Gronbaek L, Vilstrup H, Jepsen P. Autoimmune hepatitis in Denmark: incidence, prevalence, prognosis, and causes of death. A nationwide registry-based cohort study. J Hepatol. 2014;60(3):612–7.

Yoshizawa K, Joshita S, Matsumoto A, et al. Incidence and prevalence of autoimmune hepatitis in the Ueda area, Japan. Hepatol Res. 2016;46(9):878–83.

Takahashi H, Zeniya M. Acute presentation of autoimmune hepatitis: does it exist? A published work review. Hepatol Res. 2011;41(6):498–504.

Ohira H, Abe K, Takahashi A, et al. Autoimmune hepatitis: recent advances in the pathogenesis and new diagnostic guidelines in Japan. Intern Med. 2015;54(11):1323–8.

Lefkowitch JH, Apfelbaum TF, Weinberg L, et al. Acute liver biopsy lesions in early autoimmune (“lupoid”) chronic active hepatitis. Liver. 1984;4(6):379–86.

Takahashi A, Arinaga-Hino T, Ohira H, et al. Autoimmune hepatitis in Japan: trends in a nationwide survey. J Gastroenterol. 2017;52(5):631–40.

EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines. Autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2015;63(4):971–1004.

Onji M, Zeniya M, Yamamoto K, et al. Autoimmune hepatitis: diagnosis and treatment guide in Japan, 2013. Hepatol Res. 2014;44(4):368–70.

Nguyen Canh H, Harada K, Ouchi H, et al. Acute presentation of autoimmune hepatitis: a multicentre study with detailed histological evaluation in a large cohort of patients. J Clin Pathol. 2017;70(11):961–9.

Alvarez F, Berg PA, Bianchi FB, et al. International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group Report: review of criteria for diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1999;31(5):929–38.

Okano N, Yamamoto K, Sakaguchi K, et al. Clinicopathological features of acute-onset autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatol Res. 2003;25(3):263–70.

Miyake Y, Iwasaki Y, Kobashi H, et al. Autoimmune hepatitis with acute presentation in Japan. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42(1):51–4.

Hennes EM, Zeniya M, Czaja AJ, et al. Simplified criteria for the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2008;48(1):169–76.

Tiniakos DG, Brain JG, Bury YA. Role of histopathology in autoimmune hepatitis. Dig Dis. 2015;33(Suppl 2):53–64.

Muratori P, Granito A, Quarneti C, et al. Autoimmune hepatitis in Italy: the Bologna experience. J Hepatol. 2009;50(6):1210–8.

Yoshizawa K, Matsumoto A, Ichijo T, et al. Long-term outcome of Japanese patients with type 1 autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2012;56(2):668–76.

Sanchez-Urdazpal L, Czaja AJ, van Hoek B, et al. Prognostic features and role of liver transplantation in severe corticosteroid-treated autoimmune chronic active hepatitis. Hepatology. 1992;15(2):215–21.

Czaja AJ, Menon KV, Carpenter HA. Sustained remission after corticosteroid therapy for type 1 autoimmune hepatitis: a retrospective analysis. Hepatology. 2002;35(4):890–7.

Alla V, Abraham J, Siddiqui J, et al. Autoimmune hepatitis triggered by statins. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40(8):757–61.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Trevor Ralph for his English editorial assistance.

Funding

This study was conducted and supported by Health Labor Science Research Grants from Research on Measures for Intractable Diseases, the Intractable Hepato-Biliary Diseases Study Group in Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have nothing to disclose regarding funding from industries or other conflicts of interest with respect to this manuscript.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Joshita, S., Yoshizawa, K., Umemura, T. et al. Clinical features of autoimmune hepatitis with acute presentation: a Japanese nationwide survey. J Gastroenterol 53, 1079–1088 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-018-1444-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-018-1444-4