Abstract

Purpose

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is associated with treatment-related complications and poor survival in patients with head and neck cancer (HNC). We investigated the effects of frailty on HRQoL in patients with HNC receiving definitive concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT).

Methods

A total of 461 consecutive patients with locally advanced HNC who received CCRT between 2017 and 2018 at three medical centers in Taiwan were included. Frailty and HRQoL were assessed using the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment and QLQ-H&N35 before CCRT. The sum score was calculated based on the first 30 questions of QLQ-H&N35. Multivariate analysis was performed to evaluate the impact of frailty on HRQoL.

Results

The overall sum score was 39 (34–49). The sum scores of patients with impairments in 0, 1, 2, 3, and ≥ 4 frailty domains were 34 (32–38), 40 (34–47), 46 (36–55), 48 (41–64), and 56 (50–60), respectively. Patients with impairments in more frailty domains had a higher symptom burden (p for trend < 0.001). Frail patients tended to experience symptoms across all QLQ-H&N35 subscales. Sex, body mass index, tumor type, tumor stage, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, and frailty were determinants of HRQoL in the univariate analysis. Frailty was an independent determinant of HRQoL in the multivariate analysis.

Conclusion

Routine frailty assessment may serve as a surrogate for the selection of patients with HNC with poor HRQoL before CCRT. Further studies are needed to determine whether appropriate interventions in frail patients would improve their HRQoL during CCRT.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Owing to the popularity of betel quid chewing [1], head and neck cancer (HNC) has become an endemic disease and is the fifth leading cause of cancer-related death in Taiwan [2]. HNC is usually diagnosed at a locally advanced stage and cannot be resected. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) is the treatment of choice in these instances [3,4,5]. The high intensity and efficacy of CCRT are associated with a higher incidence of treatment-related morbidity and mortality [3,4,5].

Frailty is defined as an accumulative decline in physiological reserves that leads to multiple functional disabilities and increased vulnerability to subsequent morbidity and mortality [6]. Malnutrition, functional impairment, depression, and social isolation are all predisposing factors for frailty. Consequently, the prevalence of frailty is much higher in HNC than in other cancer types [7, 8]. A previous study reported that frailty was associated with higher treatment-related toxicity, poor tolerance, and poor survival in patients with HNC receiving definitive CCRT [9]. Because frail patients are more susceptible to treatment-related complications, several clinical guidelines recommend routine frailty assessment in oncogeriatric patients before providing antitumor treatments [10, 11]. However, frailty assessment has not yet become standard clinical practice in Taiwan, due to the lack of concept and the tediousness of the questionnaire.

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) reflects the impact of a disease or treatment on the patient’s perception of their physical, mental, and social health [12]. Definitive CCRT often leads to the degradation of facial appearance, taste perception, and swallowing function, which is the deterioration of HNC-specific HRQoL [3,4,5]. HNC and its treatment affect core aspects of patient perception [13]. Deterioration in HRQoL is associated with treatment-related toxicity and poor survival in patients with HNC [14].

Impaired HRQoL is frequently reported in patients who are older, dependent, have comorbidities, and lack social support, all of which are predisposing factors for frailty [15]. Previous studies have shown that frailty is associated with worse HRQoL and may serve as a surrogate for outcomes in patients with HNC [15,16,17]. These studies were limited by their retrospective nature [16], small sample size [17], and inclusion of patients receiving different treatment modalities, including surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and combination therapy [15]. We conducted this large, prospective, multicenter study to evaluate the effect of pretreatment frailty on HRQoL in patients with HNC receiving definitive CCRT.

Material and methods

Patients

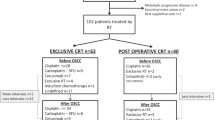

We prospectively enrolled 461 consecutive patients with HNC who received definitive CCRT with curative intent at three medical centers in Taiwan between August 2017 and December 2018. The inclusion criteria were as follows: age > 20 years, pathological diagnosis of primary HNC, and stage II–IVA disease. Patients who were unable to complete the questionnaire, who received radiotherapy or chemotherapy alone, or who did not provide written informed consent for any reason were excluded. All patients provided written informed consent before enrolment. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the CGMH (approval number: 1608080002) and was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Figure 1 shows the CONSORT diagram of the study.

Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy

All patients received intensity- or arc-modulated radiotherapy at a conventional fractionated daily dose of 200 cGy for 5 consecutive days per week, with a total prescribed dose of 7,000–7,400 cGy in 7 weeks [3,4,5]. A cisplatin-based regimen (40 mg/m2 per week or 100 mg/m2 every 3 weeks) was administered concurrently with radiotherapy [3,4,5]. Patients who received < 90% of the radiotherapy dose or who received a cumulative cisplatin dose of < 200 mg/m2 were considered to have received incomplete CCRT [18, 19].

Frailty and HRQoL assessments

All eligible patients were assessed by a trained clinical assistant using frailty and HRQoL assessments within 7 days prior to CCRT initiation.

Frailty was assessed using the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment, which includes eight domains: functional status, nutritional status, comorbidities, mobility/falls, social support, mood, cognition, and polypharmacy [9]. Patients with impairments in 0 or 1 domain were considered “non-frail,” while those with impairments in ≥ 2 domains were considered “frail.” The assessment tools and cutoff values for each domain are listed in Table 1.

HRQoL was assessed using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-H & N35 (QLQ-H&N35) [20]. Patient responses were rated on a 4-point Likert scale and converted to a scale ranging from 0 (least) to 100 (most symptoms). The sum score was calculated based on the first 30 questions, as reported previously [21].

Statistical analysis

Data are summarized as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and as median and range or interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables. The linear trend of the QLQ-H&N35 sum score and the number of impaired frailty domains (p for trend) were assessed using the Cochran–Armitage test [22]. Linear regression analysis was used to evaluate the impact of frailty on HRQoL. Clinically significant variables in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 23.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

The characteristics of the 461 patients are shown in Table 2. The median age was 54 (range: 24–86) years; 68 (14.8%) patients were aged ≥ 65 years. Men accounted for 87.2% of patients. The most common cancer sites were the oropharynx (32.8%), hypopharynx (24.9%), and nasopharynx (24.9%). Most patients (66.4%) had stage IVA/B disease; 16.7% had stage III disease.

Frailty assessment

Overall, 29.5%, 37.3%, 21.5%, 9.3%, 2.0%, 0.2%, and 0.2% of patients had impairments in 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 frailty domains of the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment, respectively. Accordingly, 308 (66.8%) and 153 (33.2%) patients were assigned to the non-frail and frail groups, respectively.

Quality of life outcomes

The frequency and severity of each symptom on the QLQ-H&N35 scale are shown in Table 3. The most prevalent symptoms were speech (77.4%), swallowing (55.5%), dry mouth (55.5%), pain (52.9%), and sticky saliva (51.6%). Sticky saliva (25.2), dry mouth (24.9), difficulty in opening the mouth (22.1), coughing (22.1), teeth (18.3), and swallowing (17.6) had the highest severity scores.

Association of HRQoL with frailty

The overall median QLQ-H&N35 sum score was 39 (IQR: 34–49). The median QLQ-H&N35 sum scores of patients with impairments in 0, 1, 2, 3, and ≥ 4 frailty domains were 34 (IQR: 32–38), 40 (IQR: 34–47), 46 (IQR: 36–55), 48 (IQR: 41–64), and 56 (IQR: 50–60), respectively (p for trend < 0.001; Fig. 2).

The impact of frailty on each symptom on the QLQ-H&N35 scale is shown in Fig. 3. Frail patients tended to experience symptoms across all QLQ-H&N35 subscales.

The impact of each frailty deficits within the CGA on HRQoL was ranked based on decreasing β-coefficient values: mood (β = 7.94, 95% CI: 4.21–11.7, p < 0.001), nutrition (β = 2.97, 95% CI: 2.54–3.40, p < 0.001), social support (β = 1.65, 95% CI: -1.83–5.12, p = 035), polypharmacy (β = 0.94, 95% CI: 0.45–1.44, p < 0.001), functionality (β = 0.47, 95% CI: 0.29–0.67, p < 0.001), Cognition (β = 0.37, 95% CI: -5.40–4.67, p = 0.89), mobility (β = 0.32, 95% CI: -4.65–4.01, p = 0.88), and comorbidity (β = 0.11, 95% CI: -0.90–1.13, p = 0.82) (Supplementary Table 1).

Univariate and multivariate analysis of HRQoL

In the univariate analysis, sex, body mass index (BMI), tumor type, tumor stage, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG-PS), and frailty were significantly associated with QLQ-H&N35 sum scores (Table 4).

After adjusting for tumor type (model 1), tumor type and tumor stage (model 2), tumor type, tumor stage, and ECOG-PS (model 3), sex, tumor stage, and ECOG-PS (model 4), and sex, BMI, tumor stage, and ECOG-PS (model 5), frailty remained an independent predictive factor for poor HRQoL (Table 5).

Quality of life and incomplete concurrent chemoradiotherapy

Totally, 46 of 461 patients (10%) had incomplete CCRT. Patients with sum score ≥ median had higher risk for incomplete CCRT (13.4% vs 6.5%, OR = 2.22, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.17–4.24, p = 0.015) than those with sum score < median. The presence of each symptom in the QLQ-HN35 group was associated with a higher risk of CCRT incompletion. The differences were significant among patients who presented with speech difficulties, illness, coughing, senses, and swallowing symptoms (supplementary Figure 1).

Discussion

Frailty is prevalent and linked to poor outcomes in patients with HNC receiving CCRT [7,8,9]. However, the impact of frailty on HRQoL in patients with HNC has not been extensively studied, especially in non-Western populations. This prospective cohort study demonstrated that frail patients tended to experience symptoms across all QLQ-H&N35 subscales. A positive linear relationship was observed between the number of impaired frailty domains and HRQoL/symptom burden. Frailty was the only modifiable factor associated with HRQoL in patients with HNC, along with non-modifiable factors such as sex, tumor stage, and ECOG-PS. Our findings suggest that frailty may be used as a surrogate for HRQoL and as an interventional tool to improve the medical care of patients with HNC.

Frailty is commonly associated with HRQoL in cancer patients. Frail patients tend to experience weight loss, limited mobility, and a lack of social support, which negatively affect their daily life and overall quality of life [16]. Similarly, patients with poor quality of life tend to experience negative effects on their psychological well-being and motivation to engage in normal physical activity, creating a vicious cycle [13]. Previous studies have found that frailty is associated with worse pretreatment HRQoL in patients with HNC [15,16,17]. However, treatment modalities vary widely and include surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy [15]. This is the first study to investigate the association between frailty and HRQoL in patients with HNC receiving definitive CCRT. Our results showed that frailty was significantly associated with worse pretreatment HRQoL, indicating that routine frailty assessment may assist physicians in identifying vulnerable patients with worse HRQoL and counseling patients regarding alternative treatment options before CCRT. Takahashi et al. [23] demonstrated that reduced-dose CCRT was associated with a favorable HRQoL outcome without compromising the long-term survival of selected patients with human papillomavirus-positive oropharyngeal carcinoma. This study used a similar approach to identify frail patients and adjust treatment accordingly to improve outcomes.

Pretreatment HRQoL is a well-known prognostic factor for short-term treatment outcomes [24] and long-term survival [21] in patients with HNC. A systematic review of 19 studies found a positive association between pretreatment HRQoL and survival in patients with HNC [25]. Using the same questionnaire as in our study, Aarstad et al. [21] showed that HRQoL has prognostic power for 10-year overall survival in patients with HNC. In addition to common symptoms such as fatigue and anorexia, patients with HNC frequently experience tumor-site symptoms such as dry mouth and speech and swallowing difficulties [20, 26]. The most severe symptoms in this study were sticky saliva, dry mouth, difficulty in opening the mouth, coughing, and swallowing, all of which are risk factors for malnutrition and odontogenic infection that could lead to treatment interruption and compromise survival [27].

In 2019, HNC was ranked the sixth most common cancer in Taiwan, with a median age of diagnosis of 57 years [2]. Only 14.8% of patients in this study were aged ≥ 65 years. A previous study indicated that the prevalence of frailty was similar in geriatric and non-geriatric cancer patients [9]. Our findings suggest that frailty, which is more predictive than age, is a determinant of HRQoL, consistent with a previous report that frailty may be assessed independently of age [9]. Our data were reinforced by multidimensional assessments to evaluate treatment outcomes and HRQoL in adult patients with HNC.

The common core features of frailty and poor HRQoL lead to an inevitable link between the number of impaired frailty domains and the risk of poor HRQoL [15,16,17]. Not surprisingly, our study showed that patients with impairments in a greater number of frailty domains had poorer HRQoL. Frail patients have poorer HRQoL than non-frail patients because they are more likely to have a low BMI, advanced tumor stage, and poor ECOG-PS [26,27,28,29]. The effect of frailty on HRQoL remained significant after adjusting for other potential confounders in the multivariate models, suggesting that improvements in frailty may improve treatment outcomes, independent of HRQoL.

Several variables, including patient characteristics, tumor features, and treatment modalities, may affect HRQoL in patients with HNC [30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. Older age [30, 31], male sex [34], comorbidities [35], depression [30, 36], and apprehensive coping strategies [35] are common characteristics of HRQoL in patients with HNC. Considering these factors may help build predictive models of HRQoL and provide valuable information for healthcare providers in terms of appropriate interventions and support to improve patient-centered care, HRQoL, and clinical outcomes.

In the multivariate analysis, the β-coefficients for HRQoL were highest for ECOG-PS and frailty. ECOG-PS is widely used in oncology practice to evaluate pretreatment physical fitness [37]. However, ECOG-PS is subjective [38]. A previous study suggested that ECOG-PS may not be appropriate for evaluating physical fitness in elderly patients with cancer [39]. Frailty assessment provides a more comprehensive evaluation of multiple dimensions to identify vulnerable patients and develop appropriate interventions.

This study showed that pre-treatment HRQoL was significantly associated with CCRT incompletion in patients with HNC. Furthermore, our data delved into the distinct impact of individual frailty deficits on HRQoL in HNC patients. We found mood and nutrition to be the most significant factors affecting HRQoL. Depressive mood and malnutrition, often linked with advanced disease stages, are inevitably associated with poorer HRQoL [40, 41]. Prompt interventions addressing mood and nutritional deficits have shown feasibility and positive effects on HRQoL and survival outcomes in HNC patients [42, 43]. Lesser yet notable effects were observed from social support, polypharmacy, functional abilities, cognitive health, mobility, and comorbidities, in descending order of their impact. These findings underscore the importance of targeted interventions that focus on these specific frailty aspects to improve HRQoL outcomes in this patient population.

This study was strengthened by the prospective cross-sectional design and the analysis of the association between pretreatment frailty and HRQoL in a large cohort of patients with HNC receiving definitive CCRT. This study also has several limitations. First, HRQoL may change over time after antitumor treatment, or potentially improve after symptom management or frailty intervention [44]. However, only baseline HRQoL data were available for this study. Second, multiple factors may influence HRQoL in patients with HNC; however, the reasons behind the variables measured were unknown. For example, difficulty in opening the mouth or swallowing may be related to trismus induced by betel quid chewing, an endemic disease in Taiwan, rather than cancer. Finally, while the QLQ-H&N35 questionnaire is commonly used for HNC-specific HRQoL, it lacks an overall quality of life assessment [20]. A sum score based on the first 30 questions of the QLQ-H&N35 questionnaire was used to represent overall quality of life [21]. Further research is needed to determine whether the sum score accurately represents overall quality of life. Additional studies are needed to assess whether appropriate interventions would improve HRQoL in frail patients during antitumor therapy.

Conclusions

Our study shows that frailty is an independent determinant of HRQoL in patients with HNC prior to definitive CCRT. Routine frailty assessment can identify patients with HNC with poor HRQoL before CCRT. Further studies are needed to determine whether appropriate interventions in frail patients would improve their HRQoL during CCRT.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CCRT:

-

Concurrent chemoradiotherapy

- ECOG-PS:

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status

- HNC:

-

Head and neck cancer

- HRQoL:

-

Health-related quality of life

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- QLQ-H&N35:

-

Quality of Life Questionnaire-H & N35

References

Hsu WL, Yu KJ, Chiang CJ, Chen TC, Wang CP (2017) Head and neck cancer incidence trends in Taiwan, 1980–2014. Int J Head Neck Sci 1:180–189. https://doi.org/10.6696/IJHNS.2017.0103.05

Cancer Registry Annual Report, 2019 Taiwan. Republic of China: Bureau of Health Promotion, Department of Health, Executive Yuan. https://twcr.tw/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Top-10-cancers-in-Taiwan-2019.pdf. Accessed January 20, 2023

Adelstein DJ, Li Y, Adams GL et al (2003) An intergroup phase III comparison of standard radiation therapy and two schedules of concurrent chemoradiotherapy in patients with unresectable squamous cell head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol 21(1):92–98. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2003.01.008

Hitt R, Grau JJ, López-Pousa A, Berrocal A et al (2014) A randomized phase III trial comparing induction chemotherapy followed by chemoradiotherapy versus chemoradiotherapy alone as treatment of unresectable head and neck cancer. Ann Oncol 25(1):216–225. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdt461

Haddad R, O’Neill A, Rabinowits G et al (2013) Induction chemotherapy followed by concurrent chemoradiotherapy (sequential chemoradiotherapy) versus concurrent chemoradiotherapy alone in locally advanced head and neck cancer (PARADIGM): A randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 14(3):257–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70011-1

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J et al (2001) Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 56(3):M146–M156. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146

van Deudekom FJ, Schimberg AS, Kallenberg MH, Slingerland M, van der Velden LA, Mooijaart SP (2017) Functional and cognitive impairment, social environment, frailty and adverse health outcomes in older patients with head and neck cancer: A systematic review. Oral Oncol 64:27–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2016.11.013

Bras L, Driessen DAJJ, de Vries J et al (2020) Patients with head and neck cancer: Are they frailer than patients with other solid malignancies? Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 29(1):e13170. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.13170

Chou WC, Chang PH, Chen PT et al (2020) Clinical significance of vulnerability assessment in patients with primary head and neck cancer undergoing definitive concurrent chemoradiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 108(3):602–611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.01.004

Mohile SG, Dale W, Somerfield MR et al (2018) Practical assessment and management of vulnerabilities in older patients receiving chemotherapy: ASCO guideline for geriatric oncology. J Clin Oncol 36(22):2326–2347. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2018.78.8687

Wildiers H, Heeren P, Puts M et al (2014) International Society of Geriatric Oncology consensus on geriatric assessment in older patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 32(24):2595–2603. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8347

US Food and Drug Administration (2006) Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims: draft guidance. Health Qual Life Outcomes 4:79. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-4-79

Yuwanati M, Gondivkar S, Sarode SC et al (2021) Oral health-related quality of life in oral cancer patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Future Oncol 17(8):979–990. https://doi.org/10.2217/fon-2020-0881

Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, van Nieuwenhuizen A, Leemans CR (2012) The value of quality-of-life questionnaires in head and neck cancer. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 20(2):142–147. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOO.0b013e32834f5fd7

de Vries J, Bras L, Sidorenkov G et al (2021) Association of deficits identified by geriatric assessment with deterioration of health-related quality of life in patients treated for head and neck cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 147(12):1089–1099. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2021.2837

Rogers SN, Waylen AE, Thomas S et al (2020) Quality of life, cognitive, physical and emotional function at diagnosis predicts head and neck cancer survival: analysis of cases from the Head and Neck 5000 study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 277(5):1515–1523. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-020-05850-x

Thomas CM, Sklar MC, Su J, Xu W, De Almeida JR, Alibhai SMH, Goldstein DP (2021) Longitudinal assessment of frailty and quality of life in patients undergoing head and neck surgery. Laryngoscope 131(7):E2232–E2242. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.29375

Garden AS, Harris J, Vokes EE et al (2004) Preliminary results of Radiation Therapy Oncology Group 97–03: A randomized phase II trial of concurrent radiation and chemotherapy for advanced squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck. J Clin Oncol 22(14):2856–2864. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2004.12.012

Loong HH, Ma BB, Leung SF et al (2012) Prognostic significance of the total dose of cisplatin administered during concurrent chemoradiotherapy in patients with locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Radiother Oncol 104(3):300–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2011.12.022

Singer S, Arraras JI, Chie WC et al (2013) Performance of the EORTC questionnaire for the assessment of quality of life in head and neck cancer patients EORTC QLQ-H&N35: a methodological review. Qual Life Res 22(8):1927–1941. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-012-0325-1

Aarstad HJ, Østhus AA, Aarstad HH, Lybak S, Aarstad AKH (2019) EORTC Quality of Life Questionnaire Head and Neck (H&N)-35 scores from H&N squamous cell carcinoma patients obtained at diagnosis and at 6, 9 and 12 months following diagnosis predict 10-year overall survival. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 276(12):3495–3505. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-019-05630-2

Armitage P (1955) Tests for linear trends in proportions and frequencies. Biometrics 11:375–386

Takahashi M, Hwang M, Misiukiewicz K et al (2022) Quality of life analysis of HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer patients in a randomized trial of reduced-dose versus standard chemoradiotherapy: 5-Year Follow-Up. Front Oncol 12:859992. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.859992

do Nascimento Santos Lima E, Ferreira IB, Lajolo PP, Paiva CE, de Paiva Maia YC, das Graças Pena G (2020) Health-related quality of life became worse in short-term during treatment in head and neck cancer patients: a prospective study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 18(1):307. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01543-5

van Nieuwenhuizen AJ, Buffart LM, Brug J, Leemans CR, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM (2015) The association between health related quality of life and survival in patients with head and neck cancer: a systematic review. Oral Oncol 51(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.09.002

Hanna EY, Mendoza TR, Rosenthal DI, Gunn GB, Sehra P, Yucel E, Cleeland CS (2015) The symptom burden of treatment-naive patients with head and neck cancer. Cancer 121(5):766–773. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29097

Østhus AA, Aarstad AK, Olofsson J, Aarstad HJ (2013) Prediction of survival by pretreatment health-related quality-of-life scores in a prospective cohort of patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 139(1):14–20. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2013.1056

Kirkhus L, Šaltytė Benth J, Grønberg BH et al (2019) Frailty identified by geriatric assessment is associated with poor functioning, high symptom burden and increased risk of physical decline in older cancer patients: Prospective observational study. Palliat Med 33(3):312–322. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216319825972

Decoster L, Quinten C, Kenis C et al (2019) Health related quality of life in older patients with solid tumors and prognostic factors for decline. J Geriatr Oncol 10(6):895–903. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2019.03.018

Chen SC, Liao CT, Chang JT (2011) Orofacial pain and predictors in oral squamous cell carcinoma patients receiving treatment. Oral Oncol 47:131–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.11.004

Wilson JA, Carding PN, Patterson JM (2011) Dysphagia after nonsurgical head and neck cancer treatment: patients’ perspectives. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 145:767–771. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599811414506

Nourissat A, Bairati I, Fortin A, Gélinas M, Nabid A, Brochet F, Têtu B, Meyer F (2012) Factors associated with weight loss during radiotherapy in patients with stage I or II head and neck cancer. Support Care Cancer 20(3):591–599. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-011-1132-x

Christianen ME, Schilstra C, Beetz I et al (2012) Predictive modelling for swallowing dysfunction after primary (chemo)radiation: results of a prospective observational study. Radiother Oncol 105(1):107–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2011.08.009

Shuman AG, Duffy SA, Ronis DL, Garetz SL, McLean SA, Fowler KE, Terrell JE (2010) Predictors of poor sleep quality among head and neck cancer patients. Laryngoscope 120(6):1166–1172. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.20924

Scharloo M, Baatenburg de Jong RJ, Langeveld TP, van Velzen-Verkaik E, Doorn-Op den Akker MM, Kaptein AA (2010) Illness cognitions in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: predicting quality of life outcome. Support Care Cancer 18(9):1137–1145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-009-0728-x

Howren MB, Christensen AJ, Karnell LH, Funk GF (2010) Health-related quality of life in head and neck cancer survivors: impact of pretreatment depressive symptoms. Health Psychol 29:65–71. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017788

Orr ST, Aisner J (1986) Performance status assessment among oncology patients: a review. Cancer Treat Rep 70:1423–1429

Simcock R, Wright J (2020) Beyond performance status. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 32:553–561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clon.2020.06.016

Ho YW, Tang WR, Chen SY, Lee SH, Chen JS, Hung YS, Chou WC (2021) Association of frailty and chemotherapy-related adverse outcomes in geriatric patients with cancer: a pilot observational study in Taiwan. Aging (Albany NY) 13(21):24192–24204. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.203673

Aarstad HJ, Aarstad AK, Heimdal JH, Olofsson J (2005) Mood, anxiety and sense of humor in head and neck cancer patients in relation to disease stage, prognosis and quality of life. Acta Otolaryngol 125(5):557–565. https://doi.org/10.1080/00016480510027547

Hsueh SW, Lai CC, Hung CY (2021) A comparison of the MNA-SF, MUST, and NRS-2002 nutritional tools in predicting treatment incompletion of concurrent chemoradiotherapy in patients with head and neck cancer. Support Care Cancer 29(9):5455–5462. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06140-w

Senchak JJ, Fang CY, Bauman JR (2019) Interventions to improve quality of life (QOL) and/or mood in patients with head and neck cancer (HNC): a review of the evidence. Cancers Head Neck 4:2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41199-019-0041-4

Ho YW, Yeh KY, Hsueh SW (2021) Impact of early nutrition counseling in head and neck cancer patients with normal nutritional status. Support Care Cancer 29(5):2777–2785. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05804-3

Rosenthal DI, Mendoza TR, Fuller CD et al (2014) Patterns of symptom burden during radiotherapy or concurrent chemoradiotherapy for head and neck cancer: a prospective analysis using the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Symptom Inventory-Head and Neck Module. Cancer 120(13):1975–1984. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28672

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support from the

Cancer Center of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taoyuan, Taiwan.

Funding

This study was supported by research grants (CMRPG3L1611 and CORPG3N0151) from Chang Gung Memorial Hospital at Linkou, Taoyuan, Taiwan, R.O.C., research grants (MOHW112-TDU-B-222–124011) from Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan, R.O.C., and research grants (NSTC 111–2314-B-182A-162 and NSTC 112–2314-B-182A-152) from National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan, R.O.C.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CHL, CYH, SWH, WCC provided the conception and design of the study; KYY, YSH, CHL, CYH, and WCC performed analysis and interpretation of data; CHL, CYH, SWH, KYY, YSH, WCC drafted of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics statements

The protocol for this research project has been approved by the suitably constituted Institutional Review Board (approval no. 201600916B0) and it conforms to the provisions of the 2013 Declaration of Helsinki. All informed consent was obtained from the subject(s).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

520_2024_8313_MOESM1_ESM.tif

Supplementary file1. Supplementary Figure 1. Effect of presence or absence of each symptomatic item in QLQ-HN35 on concurrent chemoradiotherapy incompletion among patients with head and neck cancer (TIF 426 KB)

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, CH., Hung, CY., Hsueh, SW. et al. Frailty is an independent factor for health-related quality of life in patients with head and neck cancer receiving definitive concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Support Care Cancer 32, 106 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-024-08313-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-024-08313-9