Abstract

Purpose

Despite strong demand from breast cancer survivors, there is a dearth of flexibly delivered, accessible psychological interventions addressing fear of cancer recurrence (FCR). This study aimed to explore patients’ and clinicians’ perspectives concerning the experience, utility and barriers to a novel clinician-led FCR intervention (CIFeR).

Methods

Twenty female participants (mean age, 59.8, SD = 11.43), diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer (mean years since diagnosis = 2.8, SD = 1.37 years) participated in telephone interviews, and their five oncologists completed a semi-structured electronic survey. Thematic qualitative analyses were performed on interview transcripts and survey responses.

Results

Findings indicated both patients and clinicians were positive about CIFeR with perceived cognitive, behavioural and emotional benefits of CIFeR most pronounced for patients with clinically significant FCR. All patients, however, found that receiving CIFeR (especially the tailored prognostic information) from their oncologists with whom they had a long-standing relationship added a much-needed human element to addressing FCR. Similarly, clinicians valued CIFeR as a clear and consistent way to address unmet needs around FCR, with some barriers around time, language and cultural issues noted.

Conclusion

Overall, all participants perceived CIFeR as strongly beneficial in reducing FCR and related worries, thus warranting further evaluation of its utility in clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Breast cancer prognosis has substantially improved in recent decades, yet survivors are often left with a range of unaddressed physical and psychological sequelae, including fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) [1]. FCR, the “fear, worry, or concern relating to the possibility that cancer will come back or progress” [2], is one of the most prevalent and severe unmet needs reported by cancer survivors globally [1, 3, 4]. Fifty to 70% of breast cancer survivors report moderate-to-severe FCR, while 7–10% report severe and disabling FCR [1, 3] manifesting as (1) constant and intrusive thoughts about cancer, (2) avoidant or hypervigilant behaviours (e.g. excessive symptom monitoring, missing follow-up appointments) and (3) an inability to plan for the future [4]. This characteristic combination of preoccupation, worry and hypervigilance can maintain and intensify over time, detrimentally impacting survivors’ quality of life and burdening medical and psycho-oncological resources in the health system [1, 5, 6].

Recently, psychological therapies addressing FCR have shown small, yet sustained effects in abating modifiable symptoms (e.g. perceived risk, self-efficacy, help-seeking) [7, 8]. However, these existing interventions are often resource-intensive, psychologist or nurse-delivered and inaccessible to many breast cancer survivors [9]. Oncologists — as medical experts with sustained, long-term, caring relationships with patients — are uniquely positioned to detect and manage FCR. Yet, a systematic review examining existing FCR interventions identified no doctor-led FCR interventions, with clinicians surveyed in the literature expressing discomfort in managing FCR and desire for further training [9].

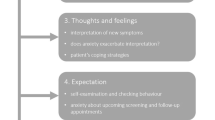

To address this gap, we designed the clinician intervention to address FCR (CIFeR) as one component in a stepped care intervention model. By matching patients’ needs to correspondingly resource-intensive interventions (i.e. low-need patients can utilise self-help Internet services; low-to-medium–need patients can receive CIFeR; those with high need can receive specialist referrals), stepped care models simplify the delivery of effective interventions [10] with randomised controlled studies indicating their value in reducing health care system burdens [11, 12]. The CIFeR intervention entailed:

-

1)

Normalising FCR — as a valid and common phenomenon within survivorship

-

2)

Providing concrete prognostic information tailored to patients’ needs and preferences

-

3)

Take-home education sheet: red-flag recurrence symptoms

-

4)

Take-home information sheet: simple psychological strategies to manage FCR-related worry and links to online resources

-

5)

Psychological referral (if appropriate)

Recently, the CIFeR single-arm phase I–II study demonstrated that oncologists could deliver CIFeR in 8 min at a follow-up consultation; CIFeR was acceptable, feasible and reduced FCR severity 3-month post-intervention [13, 14]. The current qualitative sub-study complements the quantitative CIFeR data, by exploring patients’ and clinicians’ experiences of receiving and delivering the CIFER intervention. It aims to examine the perceived utility of individual CIFeR components and clinical barriers to widespread adoption of CIFeR in routine cancer care. Given this is an exploratory study, no a priori hypotheses regarding patient and clinician perspectives on CIFeR were prepared.

Methods

Participants

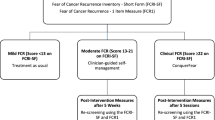

Female, early-stage (I–III inclusive) breast cancer survivors who had participated in the CIFeR study were eligible [13,14,15]. Inclusion criteria were women ≥ 18 years old, at least 6-month to 5-year post-treatment (i.e. surgery, adjuvant chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy) and proficient in English, with a fear of cancer recurrence inventory (FCRI) [13,14,15] severity subscale score > 0.

Measures

Patients participated in a single semi-structured phone interview (see Table 4), exploring their experience of the overall intervention, specific intervention components and views on how CIFeR could best be delivered to survivors in routine care. Oncologists completed a 16-item online survey (with Likert scale and open-ended questions) which explored barriers and facilitators to integrating CIFeR into clinical practice (see Supplementary file).

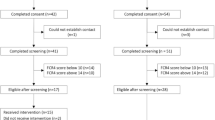

Procedure

A convenience sample of CIFeR participants, who at the time of the main study consented to this qualitative sub-study, was approached via telephone 1–3-month post-intervention, to participate in a 30-min telephone interview, at any private, convenient location with a trained female qualitative research assistant (AS). Participants had no prior relationship or knowledge of research assistant and their motivations for involvement in this study. Recruitment continued, with field notes recorded during the interviews until the saturation of themes was achieved at twenty participants. All five participating oncologists were emailed a brief REDCap survey at the conclusion of patient recruitment (6-month post-initial recruitment). Ethical approval was obtained, and all participants provided written informed consent to participate.

Data analysis

Patient interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim (not returned to participants for comment) and analysed using six phases of thematic analysis, (1) data familiarisation, (2) initial coding and inferences, (3) code combination into overarching themes, (4) examination of coherence with theoretical perspective, (5) theme description and definition and (6) checking for meaningful themes, validity and reliability across coders and participants (e.g. “member checking”) [17]. Two reviewers followed this iterative data-driven approach, double coding 30% of the interviews to ensure consistency and quality (discrepancies resolved through discussion) across two rounds of coding [18], stored in Microsoft Word and Excel files. Data were then compared for those with clinically significant (defined as total FCRI score ≥ 13) [15] versus subclinical FCR (total FCRI [15] score ≤ 13). Qualitative analyses were pre-planned and registered on the Australia and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (Ref no. ACTRN12618001615279) as part of the overall CIFeR study.

Results

Twenty of 61 breast cancer survivors participating in CIFeR and all five oncologists were recruited to the qualitative sub-study, with no attrition recorded. Independent t-tests and chi-squared testing indicated no differences between survivor interview participants and remaining CIFeR participants on age, years since diagnosis, education level or marital status (see Table 1).

Demographics

Survivors on average were 59.8 years old, with 12 women (60%) university educated and nine (45%) born outside of Australia (see Table 1). All participating oncologists were female, currently working at two large urban hospitals, on average 44.6 years old (SD = 9.4 years)Footnote 1 with 13.8 years (SD = 9.4 years) of oncology experience.

Patients’ perspectives on CIFeR

On average, patient interviews lasted 30.64 min (SD = 13.18 min), ranging from 15 to 58 min. Almost all patients interviewed (n = 19/20) would recommend the CIFeR intervention to others, except one participant who felt that patients should not require any peer recommendation to raise FCR with their oncologist. Two overarching themes (content and context) emerged in patient accounts (see Table 2 for additional quotes).

-

A.

Intervention content

Human, holistic intervention

All patients found the “human element” across the five-component CIFeR intervention holistically addressed their needs and unique personhoods, by reinforcing continuity of care and support across their cancer journey. CIFeR strengthened participants’ relationship with their oncologist: “I left feeling quite positive, I felt she was very open with me…when you are looking for establishing a professional relationship, I look for the openness and candidness, the feeling there is some form of mutual respect to who I am as an individual” (ID 154, high FCR) while retaining the opportunity for specialist involvement (clinical psycho-oncologist or counsellor). In addition, CIFeR provided reassurance, permission and space for patients to explore their fears around FCR and other mental health concerns, with one patient stating “The list of things people want to talk about could be small but knowing it doesn’t bother them [doctors] to discuss it is very helpful” (PID 49, high FCR) (Tables 3 and 4).

The initial normalisation component also provided the acknowledgement, permission and safety required for women to begin discussing and clarifying misinformation contributing to FCR. Even women with low FCR severity scores pre-intervention perceived value in CIFeR, stating “Absolutely, I recommend that doctors talk about this to their patients. There are a huge number of patients who have quite significant fears around it. I actually think that everyone going through this should be screening, it should be a standard” (PID125, low FCR).

Patients’ self-efficacy and confidence in managing their FCR

All patients felt CIFeR afforded them opportunities to address concrete aspects of survivorship (i.e. tailored, prognostic information), with most feeling confident enough to self-monitor and manage their FCR as a result: “I cut down on the crazy google searching. I realised I could get my stats, specifically, my risk, my grade, I walked away with my own stats and just to see that 1% on the paper, that was helpful. Personalised stats were really helpful. Google is way too generic. Tangible quantitative information. That was amazing, my Dr is amazing” (PID168, high FCR).

Most surveyed patients (n = 16) kept the take-home information sheets on red-flag recurrence symptoms and strategies to manage FCR, despite nine patients indicating prior use and familiarity with worry management and coping strategies detailed in CIFeR. These included reframing survivorship as a “second chance at life”, help-seeking (i.e. talking to family, friends) (PID138, clinically significant FCR) and distraction through absorbing activities like puzzles (PID87, low FCR) or pilates (PID242, low FCR). Patients nonetheless valued the spectrum of cognitive, emotional and behavioural coping approaches in CIFeR finding it “helpful because she [oncologist] …told me not to dwell on it and let it take over…. If it comes into mind, I learnt to get active, get out in garden. I used to think about it a couple of times a month; now once a month or less, so it has helped me a lot” (PID50, high FCR).

Finally, most interviewed patients appreciated yet declined psychological referrals, often noting sufficient external support sources (i.e. friends, family, GPs) and beliefs that others with worse prognoses would more greatly benefit from specialist psycho-oncology services. The two patients who accepted referrals to psycho-oncology services indicated an inability to anticipate and buffer the impact of FCR on their daily lives and poor pre-existing social supports. These patients felt exploring their FCR beyond the scope of CIFeR, normalised help-seeking, fortified their trust in their oncologist and bolstered their own confidence and competence in coping: “it prompted me to get help. I didn’t choose the same person, but just the idea of being told to see someone was planted, it’s ok to need someone. Going to therapy was one of the best things I’ve done” (PID168, high FCR).

-

B.

Context of CIFeR intervention delivery

Many patients felt contextual factors (i.e. timing, integration with standard care) facilitated their engagement with the CIFeR intervention. Whilst timing preferences varied, most participants agreed that delivering CIFeR immediately to 6-month post-treatment was most beneficial because it coincided with emerging needs to cope with isolation and vulnerability due to transitioning to survivorship (i.e. reduced daily access to services and their treating oncology team) and life events (i.e. death in family or friends). Furthermore, patients felt that delivery at a routine follow-up consultation increased feasibility both for themselves and the health system, stating “Less worry, no negatives it’s a good intervention point, everything is almost done and dusted, maybe the doctor could spend another 5 or 10 with me and it’s a time she was seeing me anyway, it’s not going to cost the system that much more and it will probably save other resources” (PID135, high FCR).

Oncologists’ perspectives on CIFeR

Practical benefits and ease of integrating CIFeR intervention

All five participating clinicians perceived CIFeR as fast and moderately to very useful and helpful. Clinicians’ perceived the delivery of CIFeR to take 0–5 min (n = 2) to 6–10 min (n = 3), which matched objective measures indicating CIFeR delivery took 8 min on average.14 All clinicians indicated they had used CIFeR with patients outside the study and would very likely continue using it in future: “Some women were reporting FCR many years later, and discussion was beneficial. Reminds us of the importance of discussing this topic with every patient during recovery from their treatment phase” (CID 242).

Usefulness of specific CIFeR components

Participating oncologists named the most useful components of CiFeR as normalisation (n = 5), provision of prognostic information (n = 3), the take-home information sheet (n = 3), information distinguishing recurrence from other symptoms (n = 2) and referral to a psycho-oncology service (n = 1). Specifically, all clinicians found utility in normalising FCR and discussing prognostic information, especially for highly anxious women, as: “something that is so obvious that we don't talk about it but it is so easy to say and I think has a huge impact for the patient knowing it is normal” (CID128).

After these frank discussions, oncologists noted most patients appeared significantly less anxious, with three oncologists stating the take-home sheets helped patients comfortably disclose their issues around FCR and seek help in their own time rather than seeking professional psycho-oncology referral. One clinician also stated that CIFeR introduced consistency by routinely reminding survivors about prognosis, as “some patients forget they’ve had chats about prognosis. Hence some believe that their risk of recurrence is much higher than it really is” (CID270) and that this reduced survivors’ anxiety in later conversations about their risk of developing recurrence of their breast cancer.

Challenges and barriers to implementing CIFeR

Most clinicians perceived prognosis (n = 4) and psychological issues (n = 1) as the most challenging (albeit useful) components of CIFeR to discuss with patients. Some clinicians noted their own discomfort in discussing prognosis as “If a patient had a high-risk cancer it can be tricky/scary telling them when you are not sure if they have understood their prognosis since diagnosis” (CID128). Others noted difficulties around estimating absolute risk, patients refusing survival statistics after treatment and in convincing patients to accept counselling referrals.

Suggested barriers to using CIFeR in routine care included time limitations and language and cultural issues in delivering CIFeR to non-English speaking survivors, whilst two oncologists reported no barriers and high survivor interest and acceptance. Only two changes were suggested to improve the intervention — providing oncologists with a “tick box” list of topics to address and screening patients to assess their needs around FCR. Barriers aside, all five clinicians were enthusiastic about routine use of CIFeR, stating it addressed an important survivor need, through a clear, simple and consistent structure. Oncologists also suggested offering CIFeR at the time of treatment completion or endocrine tolerability review and involving registrars in its delivery.

Discussion

As FCR continues to impact an expanding survivorship population [4], patients and clinicians will likely benefit from incorporating stepped, FCR interventions into routine clinical oncology practice [9,10,11,12]. Whilst a few FCR-targeted supportive care interventions delivered by non-psychosocial staff have shown feasibility in clinic, they are typically nurse-led and resource-intensive [9]. This CIFeR intervention aimed to provide a novel, efficacious and efficient clinical pathway to addressing FCR with inherently low resource costs (i.e. low clinical time dedicated to intervention delivery, training and implementation costs, psycho-oncologist referral load). This qualitative sub-study unpacked patients’ and clinicians’ experiences, respectively, of receiving and delivering the CIFeR intervention.

Both patients (across the FCR spectrum) and clinicians found CIFeR enhanced their clinical follow-up experience in a clear, structured and empathetic manner. Patients, especially those with clinically significant FCR, highly valued three CIFeR components: normalising FCR, re-iterating prognostic information and clarifying recurrence symptoms. These were reported to engender a warm, compassionate space in which to raise fears, correct misunderstandings about recurrence risks and increase patients’ self-efficacy in managing physical symptoms (i.e. distinguishing normal aging pains from recurrence symptoms). Furthermore, many patients interviewed reported greater engagement in their own FCR management and a reduced need for specialist psychological services to treat their FCR, as a result of CIFeR. Whilst interviews revealed reticence to accept referrals (due to patients feeling adequately supported), those who took up referrals felt supported by their oncologist and found therapy a worthwhile experience.

Importantly, patients perceived CIFeR as person-centric: strongly appreciating their clinician’s “whole person” approach, which valued their mental and physical health. This valued patients placed in holistic care is consistent with findings of a recent systematic review of 29 primarily qualitative studies examining patients’ needs, values and preferences in oncology care [19]. Review findings noted successful patient-centred care prioritised supporting patient values (autonomy, sincerity and hope) and flexibility in coordinating care and accommodating preferences for information delivery and shared decision-making [19,20,21], much of which is featured in CIFeR.

Participating oncologists reported that CIFeR provided a structured, stepped approach to identifying and managing FCR. Four of the five surveyed oncologists found FCR management to be challenging, which is comparable to other surveys of oncology clinicians, suggesting up to 96% of oncologists associate some level of challenge with FCR management [22, 23]. Thewes et al. [22], for example, indicated the majority of clinicians surveyed viewed managing FCR as somewhat (52.7%) to moderately (32.4%) challenging with all study participants (oncologists and other health professionals) interested in further FCR management training. Thus, CIFeR appears to be meeting a currently unaddressed need for oncologist education on this topic. Practical ways to potentially further increase the utility of CIFeR include introducing routine FCR screening in clinic (as suggested by participating oncologists) and incorporating a checklist of CIFeR steps for oncologists.

Both patients and clinicians ideally felt delivering CIFeR at treatment end during follow-up could consolidate patients’ understanding of prognosis and help them self-manage detecting signs of recurrence and emotional responses. Importantly, patients also observed that delivering CIFeR during a routine consultation may improve uptake without utilising other resources unnecessarily (i.e. psycho-oncologists, breast care nurses, patient travel time), highlighting an important sustainability feature of the intervention. Schell et al. [24] demonstrate potential intervention benefits are closely related to sustainability. Delivering CIFeR via current, trusted staff, within an existing consultation, could likely provide a cost-effective and sustainable approach for oncologists to address FCR.

Study findings, however, must be considered in light of limitations. This sample was largely homogenous, with predominantly Caucasian married women over 50 years of age, limiting cross-cultural generalisability of findings. A core study design strength involved using semi-structured interviews to facilitate in-depth comparison and contrast of stakeholder (clinician and patient) perspectives, yet wider interest in CIFeR uptake remains unclear.

Conclusions

This study suggests that an oncologist-delivered FCR intervention can provide an important stepped care model to reduce referral loads for psycho-oncology services. Oncologists, as experts in evidence-based medicine, can uniquely help reduce patients’ FCR through tailoring prognostic and potential recurrence symptom information to suit patient preferences and clinical circumstances. Furthermore, delivering CIFeR can consolidate the doctor–patient relationship and increase patients’ likelihood of engaging in FCR management by reinforcing perceptions they are at the centre of care provision. CIFeR appears to address a significant unmet educational need amongst oncologists, through its brief, evidence-based model for managing and ameliorating FCR symptoms. The strong qualitative support for integrating CIFeR into routine care shown by patients and clinicians alike will provide a foundation for a future implementation study.

Data availability

Data is available in de-identified form as an Excel spreadsheet on OSF under the link: https://osf.io/s9djt/files/.

Code availability

N/A.

Notes

One clinician participant did not specify their exact age or years in oncology, replying they were in their “late 40 s” and spent “15 to 20 years” in the profession. In order to proceed with analyses, the missing data were substituted with the mean values for age (47 years, between 45 and 50 years) and years of experience (17 years, between 15 and 20 years) within the boundaries specified by the participant, per Salkind [16]. No other missing data was recorded.

References

Simard S, Thewes B, Humphris G, Dixon M, Hayden C, Mireskandari S, Ozakinci G (2013) Fear of cancer recurrence in adult cancer survivors: a systematic review of quantitative studies. J Cancer Surviv 7(3):300–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-013-0272-z

Lebel S, Ozakinci G, Humphris G et al (2016) From normal response to clinical problem: definition and clinical features of fear of cancer recurrence. Support Care Cancer 24(8):3265–3268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3272-5

Thewes B, Butow P, Bell ML et al (2012) Fear of cancer recurrence in young women with a history of early-stage breast cancer: a cross-sectional study of prevalence and association with health behaviours. Support Care Cancer 20:2651–2659. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-011-1371-x

Butow P, Sharpe L, Thewes B et al (2018) Fear of cancer recurrence: a practical guide for clinicians. Oncology (Williston Park) 32(1):32-38. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29447419/

Lebel S et al (2017) Current state and future prospects of research on fear of cancer recurrence. Psychooncology 26(4):424–427. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4103

Fardell JE et al (2016) Fear of cancer recurrence: a theoretical review and novel cognitive processing formulation. J Cancer Surviv 10(4):663–673. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-015-0512-5

Tauber NM, O’Toole MS, Dinkel A et al (2019) Effect of psychological intervention on fear of cancer recurrence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol 37:2899–2915. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.19.00572

Cessna Palas JM, Hyland KA, Nelson AM et al (2020) An examination of the relationship of patient modifiable and non-modifiable characteristics with fear of cancer recurrence among colorectal cancer survivors. Supportive Care Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05552-4

Liu JJ, Butow P, Beith J (2019) Systematic review of interventions by non-mental health specialists for managing fear of cancer recurrence in adult cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 8:1–3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04979-8

Lynch FA, Katona L, Jefford M, Smith AB, Shaw J, Dhillon HM, Ellen S, Phipps-Nelson J, Lai-Kwon J, Milne D, Russell L (2020) Feasibility and acceptability of fear-less: a stepped-care program to manage fear of cancer recurrence in people with metastatic melanoma. J Clin Med 9(9):2969. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9092969

Krebber AM, Leemans CR, de Bree R, van Straten A, Smit F, Smit EF, Becker A, Eeckhout GM, Beekman AT, Cuijpers P, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM (2012) Stepped care targeting psychological distress in head and neck and lung cancer patients: a randomized clinical trial. BMC Cancer 12(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-12-173

Hauffman A, Alfonsson S, Bill-Axelson A, Bergkvist L, Forslund M, Mattsson S, von Essen L, Nygren P, Igelström H, Johansson B (2020) Cocreated internet-based stepped care for individuals with cancer and concurrent symptoms of anxiety and depression: results from the U-CARE AdultCan randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5489

Liu J et al (2020) CIFeR: A novel clinician-lead intervention to address fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) in breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 38(15):12115–12115. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2020.38.15_suppl.12115

Liu J, Butow P, Bui KT, Serafimovska A, Costa DS, Kiely BE, Hui MN, Goodwin A, McNeil CM, Beith JM (2021) Novel clinician-lead intervention to address fear of cancer recurrence in breast cancer survivors. JCO Oncology Practice OP-20 https://doi.org/10.1200/OP.20.00799

Simard S, Savard J (2009) Fear of cancer recurrence inventory: development and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of fear of cancer recurrence. Supportive Care Cancer 17:241–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-008-0444-y

Salkind, N. J (2010). Encyclopedia of research design (Vols. 1–0). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412961288

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3(2):77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, Moules NJ (2017) Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International journal of qualitative methods 28;16(1):1609406917733847. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847

Mitchell KA, Brassil KJ, Rodriguez SA, Tsai E, Fujimoto K, Krause KJ, Shay LA, Springer AE (2020) Operationalizing patient-centered cancer care: a systematic review and synthesis of the qualitative literature on cancer patients’ needs, values, and preferences. Psychooncology. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5500

Grassi L, Mezzich JE, Nanni MG, Riba MB, Sabato S, Caruso R (2017) A person-centred approach in medicine to reduce the psychosocial and existential burden of chronic and life-threatening medical illness. Int Rev Psychiatry 29(5):377–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2017.1294558

Grassi L, Spiegel D, Riba M (2017) Advancing psychosocial care in cancer patients. F1000Res 6:2083. Published 2017 Dec 4. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.11902.1https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5717468/

Thewes B, Brebach R, Dzidowska M, Rhodes P, Sharpe L, Butow P (2014) Current approaches to managing fear of cancer recurrence; a descriptive survey of psychosocial and clinical health professionals. Psychooncology 23(4):390–396. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3423

Berrett-Abebe J, Cadet T, Vitello J, Maramaldi P (2018) Developing content for an interprofessional training on fear of cancer recurrence (FCR): key informant interviews of healthcare professionals, researchers and cancer survivors. J Psychosoc Oncol 36(3):259–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347332.2018.1443987

Schell SF, Luke DA, Schooley MW, Elliott MB, Herbers SH, Mueller NB, Bunger AC (2013) Public health program capacity for sustainability: a new framework. Implementation Sci 8:15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-15

Acknowledgements

The research team would like to thank all participating patients, oncologists and research staff who contributed their time and insights.

Funding

The Avant Foundation and Sydney Breast Cancer Foundation funded this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jia Liu, Phyllis Butow and Jane Beith conceived and developed the study design. Material preparation, data collection and analyses were completed by Anastasia Serafimovska, Jia Liu and Jane Beith. Anastasia Serafimovska conducted all interviews, with Phyllis Butow also analysing qualitative findings. All authors commented on the first draft of the manuscript by Anastasia Serafimovska, and all authors contributed to and approved the manuscript in preparation for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

All phases of this study were conducted in line with the principles of the 1964 Helsinki Declaration. Ethical approval was gained on the 27th of September 2019 from Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee (CRGH Zone) (Reference: HREC/18/CRGH/237) and University of Sydney Human Ethics committee prior to study commencement. All study phases (i.e. data collection, analysis and presentation) were conducted in adherence with these ethical standards around data protection, confidentiality and privacy.

Consent to participate and consent for publication

All participants provided fully informed consent to participate in this study and for their data to be published in aggregate (de-identified) format.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This study was prospectively registered on the 2nd of October 2018 in the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12618001615279).

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Serafimovska, A., Liu, J., Beith, J. et al. Patients’ and oncologists’ perspectives on a novel Clinician-led Fear of Cancer Recurrence (CIFeR) Intervention . Support Care Cancer 29, 7637–7646 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06336-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06336-0