Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to examine the associations between self-reported spiritual/religious concerns and age, gender, and emotional challenges among cancer survivors who have completed a 5-day rehabilitation course at a rehabilitation center in Denmark (the former RehabiliteringsCenter Dallund (RC Dallund)).

Methods

The data stem from the so-called Dallund Scale which was adapted from the NCCN Distress Thermometer and comprised questions to identify problems and concerns of a physical, psychosocial, and spiritual/religious nature. Descriptive statistics were performed using means for continuous variables and frequencies for categorical variables. Odds ratios were calculated by logistic regression.

Results

In total, 6640 participants filled in the questionnaire. Among participants, 21% reported one or more spiritual/religious concerns, the most reported concerns related to existence and guilt. Having one or more spiritual/religious concerns was significantly associated with age (OR 0.88), female gender (OR 1.38), and by those reporting emotional problems such as being without hope (OR 2.51), depressed (OR 1.49), and/or anxious (OR 1.95). Among participants, 8% stated they needed help concerning spiritual/religious concerns.

Conclusions

Cancer patients, living in a highly secular country, report a significant frequency of spiritual/religious and existential concerns. Such concerns are mostly reported by the young, female survivors and by those reporting emotional challenges. Spiritual/religious and existential concerns are often times tabooed in secular societies, despite being present in patients. Our results call for an increased systemic attention among health professionals to these concerns, and a particular focus on identifying and meeting the spiritual/religious and existential concerns of women, the young and those challenged by hopelessness, depression, and anxiety.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In most Western countries, significant improvements in cancer survival in the past decade have given rise to a new reality of cancer survivorship and rehabilitation. As a consequence, and with the purpose of generating knowledge about how best to provide survivorship care, a large number of research studies have investigated how cancer survivors experience their everyday lives post-treatment [1].

Findings show that apart from suffering from physical, psychological, and social late effects, cancer survivors frequently experience multiple spiritual/religious and existential concerns, in many cases leading to distress that impacts negatively on their mental health [2]. Having completed their biomedical treatment, many cancer survivors feel alienated within their life and body, struggling with the challenge of integrating meaningfully into their lives [3].

A vast body of literature investigating the impact of spiritual/religious and existential factors on coping and meaning-making related to cancer demonstrate that spirituality and religiousness may constitute important coping resources to many cancer survivors; furthermore, that empirical links can be established between spirituality/religiousness and psychological well-being, adjustment to late effects and stress-related growth [4]. Given this evidence base, clinicians and researchers working within the field of psycho-oncology have stressed the importance of enhancing a focus on interventions that are attentive to cancer patients’ and cancer survivors’ spiritual/religious ways of meaning-making and coping [5, 6].

Although associations have been identified in a large number of international studies between spiritual/religious factors, existential meaning-making, and psychological adaptation to cancer, the question of what role spirituality/religiousness might play for cancer survivors in highly secular cultures such as Denmark has only received limited attention in a clinical setting and within Danish cancer survivorship research. Part of the reason for this lack of attention on spiritual/religious aspects of cancer survivorship might be due to the fact that spirituality/religiousness is assigned low priority and assumed by many to play an insignificant role in the lives of most Danes. Because of society’s predominant secular nature, many consider Denmark to be a “Society without God” [7]. Supporting this assumption, results of social surveys show that the majority of Danes are reluctant to identify themselves as “religious”; however, around 70% see themselves as “believers” [8, 9].

Findings from the few studies that have investigated the influence of spirituality/religiosity on adjustment to and coping with cancer and survivorship show that many cancer survivors experience problems (harmful or unwanted matters that should be dealt with), concerns (i.e., worries, preoccupations, disquietness), and needs (i.e., requirements for physical and mental well-being) of an existential nature, that spiritual/religious beliefs are experienced to be positive coping resources and that spiritual well-being is associated with reduced levels of distress and better mental adjustment [10,11,12]. Studies also found that women, older people, and those who are emotionally challenged are more oriented towards spirituality and religion than the average population [13,14,15]. A survey study based on responses from 1043 cancer survivors attending a rehabilitation course at Rehabilitation Centre Dallund (RcDallund) in Denmark from 2006 to 2008 found spiritual well-being to be associated with less distress and better mental adjustment [12]. However, it found specific aspects of faith to be both positively and negatively associated with distress and mental adjustment, highlighting “the complexity of associations between spiritual well-being and specific aspects of faith with psychological function among cancer survivors”. Thus, many studies confirm that religion may be not only a resource in the lives of cancer survivors but that they may experience concerns of a spiritual/religious and existential nature [16,17,18] and that such concerns require competent and systemic attention and care [19]. These results point to the importance of incorporating an assessment of existential and spiritual/religious concerns among Danish cancer survivors in order to provide them with a survivorship care that helps them restore a life of meaningfulness and well-being.

Thus, the purpose of this study was to examine the associations between self-reported spiritual/religious concerns and age, gender, and emotional challenges among cancer survivors who have completed a 5-day rehabilitation course at the former RcDallund.

We thus propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Older cancer survivors report more spiritual/religious concerns than younger.

Hypothesis 2: Women report more spiritual/religious concerns than men.

Hypothesis 3: Those who are emotionally challenged experience more spiritual/religious concerns than their counterparts.

Methods

Setting and population

The setting in this study was RcDallund that was established in 2001 by the Danish Cancer Society. The establishment of RcDallund can be seen as forming part of a development process in the middle of the 1990s, during which the broader focus on psychosocial problems pertaining to cancer was evolved into a more specific focus on cancer rehabilitation, including psychosocial issues [20]. RcDallund was the first rehabilitation center in Denmark to offer rehabilitation to cancer survivors in the form of a residential program. RcDallund was housed in a restored mediaeval castle in a scenic rural area. The rehabilitation intervention was a coordinated initiative with several cooperating specialists. The program focused on meeting physical, psychological, social, work-related, and existential needs through bodily and cognitive activities (lectures, group discussion sessions, individual consultations with specialists, creative arts, leisure and activities in nature, etc.). Each participant could choose one consultation with one of the specialists. All participants devised an action plan for the future at the end of their stay. Each week, 20 cancer survivors attended the week long course following the same overall schedule. However, in order to recruit cancer survivors with similar challenges, every week focused on a specific theme that was for example based on a diagnosis (e.g., breast cancer, gynecological cancer), late effect (e.g., lymphedema, fatigue, having an ostomy), or life situation (e.g., being young of age, having children, returning to work, suffering from incurable cancer). All participants were referred by a physician, and they could rank three rehabilitation weeks they wished to attend, from a published program. RcDallund’s annual capacity was around 700 participants [21].

Since 1st of January 2013, the Region of Southern Denmark (one of the five administrative units in Denmark) took over the center in a series of implemented changes in which RcDallund moved out of the Dallund Castle in 2015 and was transformed and merged with PAVI—the former Danish Knowledge Center for Palliative Care into a national knowledge center for rehabilitation and palliation based at Nyborg Hospital (REHPA—see www.rehpa.dk). Research and rehabilitation courses continue in this new setting.

Data collection

The following information was obtained from all participants attending the residential courses at RCDallund: information about diagnosis, treatment, current disease status (obtained from referring physician), marital status, education, and employment status. From 2004, all participants filled in The Dallund Scale that was inspired by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCC) Distress Thermometer and Problem List, first developed by Andrew Roth and colleagues in 1998 [22] and later translated to and validated across many languages and cancer settings [23, 24]. The Danish Dallund version was adapted and further developed by Kristensen on the basis of Dallund experience, earlier visitation instruments, and interviews in focus groups [25, 26]. The first version of the Dallund Scale was tested with two rounds of course participants (36 total), resulting in further optimization, mainly towards linguistic clarity. This optimized version of the Dallund Scale was then tested twice over 2 weeks with 102 healthy blood donors and 88 random earlier course participants. Test-retest reliability was performed resulting in Cronbach’s alpha scores of > 0.81. These were followed by statistical factor analyses indicating the Dallund Scale contained six factors with high internal consistency that resulted in the final structure of the Dallund Scale.

The Dallund Scale is thus a short questionnaire comprising, firstly, the question of how close or how far the respondents perceive they are from achieving their personal rehabilitation goals (indicating their assessment on a 10-step scale with 1 indicating “Very close” and 10 “Infinitely far away”). Secondly, the Dallund Scale comprised six batteries of items indicating problems and concerns, which inhibited the achievement of their rehabilitation goals, where participants could tick a box indicating whether they had the problem or concern. These six batteries related to various problems: eight practical, six work-related, two related to family, eight physical, and 29 psychological “problems” as well as to five spiritual/religious “concerns,” and the total of these problems and concerns qualified to what degree they had not yet arrived where they wanted to be in their cancer trajectory. All questions were added on the basis of extensive literature searches.

For the spiritual/religious concerns, respondents could tick a box indicating whether they had any or all of the five concerns relating to “God,” “faith,” “moral,” “guilt,” “existence,” and/or “other concerns” and finally whether they needed help to handle these concerns. For the psychological concerns, respondents could indicate whether they were “worried,” “sad,” “hopeless,” “lonely,” “depressed,” “nervous,” “stressed,” or “anxious,” or whether they experienced “other emotional problems”, and finally, whether they needed help. The purpose of filling in the questionnaire was twofold: To be able to plan an individualized program for each participant during the rehabilitation week at Dallund and to be able to analyze the results for research purposes.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.3. Descriptive statistics were performed by using means for continuous variables and frequencies for categorical variables. Age at the beginning of the rehabilitation stay was calculated, and age groups were coded in the following groups: < 40, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, and > 70 years. Cancer diagnosis was grouped according to cancer site into either breast cancer or other diagnosis. Odds ratios for reporting spiritual/religious concerns were calculated by logistic regression (proc logistic) with the spiritual/religious concerns as dependent variable (0/1) and age decades, gender, being without hope (0/1), depressed (0/1), and anxious (0/1) as independent variables in the model. In a further calculation, marital and employment status was included in the logistic regression to test a possible impact. Results are presented as odds ratios and thus a value below 1 means lower odds and a value of more than 1 higher odds of having the spiritual/religious concern in each column. We did not make any corrections as this is an explorative study that does not allow researchers to draw solid conclusions and because Bonferroni will lower the risk of a type I error, but increase the probability of a type II error [27].

Results

From 2004 to 2015, RcDallund conducted 360 rehabilitation weeks. Out of 6640 participants, 6640 (100%) completed the questionnaire 2 to 4 weeks prior to their stay. Most of the participants were women (86%) and the most common diagnosis was breast cancer. The women were on average younger (54.8 ± 11.0 years) than the men (59.7 ± 12.1 years). Characteristics of the population are shown in Table 1.

The frequency of self-reported spiritual/religious concerns is seen in Table 1. Among participants, 21% reported one or more spiritual/religious concerns. Concerns related to existence (11%) and guilt (8%) were the most commonly reported spiritual/religious concerns. Younger women reported spiritual/existential concerns more often than men (Fig. 1). For both genders, the existential concerns were most common among younger participants.

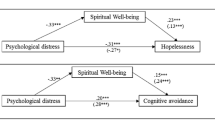

Emotional problems were reported by the participants more often than spiritual/religious concerns. “Being concerned” was the most common emotional problem, reported by 57% of all participants. Women reported more psychological problems than men. For both genders, those being without hope reported a high level of spiritual/existential concerns (Fig. 2).

Percentage with spiritual/religious concerns among all cancer survivors who participated in a 1-week rehabilitation stay from 2004 to 2015 and among the subsample who also reported that they had problems with being without hope, depressed, and anxious. See Table 2 for statistical significance of the variables

Logistic regression analysis showed that age group, gender, being without hope, being anxious, and being depressed were all associated with all three spiritual/religious concerns (one or more spiritual concerns/in relation to existence/do you need help?). Table 2 shows adjusted odds ratios, where all the dependent variables were in the model, for these three spiritual/religious items.

Crude analysis with one dependent variable at a time showed higher point estimates, but they were in the same magnitude. Diagnosis and year at RcDallund were not significant, neither in crude nor adjusted logistic regression analyses. Inclusion of marital and employment status did not change the point estimates much. The frequencies of spiritual/religious concerns by age group are presented in Fig. 1 and self-reported emotional problems in Fig. 2.

Discussion

This paper is the first large-scale study on spiritual/religious and existential concerns of cancer survivors in a highly secular country focusing on association with age, gender, and emotional challenges. We found that 21% of cancer survivors attending a rehabilitation course reported one or more spiritual/religious concerns. The most frequently reported spiritual/religious concerns in our study were related to guilt/blame (women (W) 8.8%; men (M) 4.1%) and existence (W 11. 5%; M 8.9%). We furthermore found significant associations with age, gender, and emotional problems. Concerns regarding guilt and existence were most commonly reported by women, young participants, and participants who also reported that they were without hope, depressed, and/or anxious.

Our overall findings on reported spiritual/religious concerns are in line with former studies, both qualitative and quantitative, demonstrating that spiritual/religious concerns and emotional problems are present in all treatment and survivorship stages of cancer. Receiving a cancer diagnosis has been described as evoking existential problems related to control, guilt and shame, identity, meaning, relationships, and mortality [2]. Negative associations between these existential problems and physical health, psychological adjustment, and spiritual well-being have been acknowledged [28]. Survivorship research into the existential consequences of a cancer disease show that the transition from active treatment to post-treatment and long-term survivorship is a critical time, when the biomedical treatment may leave the individual feeling alienated within his or her life and body, and in surroundings in which the individual no longer feels at home [29, 30]. Existential problems in these post-treatment phases are related to the challenges of how to integrate the experience of illness and treatment into life [3].

Whereas spiritual/religious concerns related to existence constituted the largest percentage in our study, spiritual/religious concerns in relation to God (W 2.2%; M 2.3%), faith (W 3.6%; M 3.1%), and morality (W 1.6%; M 1.7%) were less frequently reported. These findings might reflect the cultural context in which the participants are embedded. It is plausible to assume that individuals embedded in a highly secular culture [7, 31] relate to more secular concepts such as guilt, blame, and existence than to the more traditional religious concepts such as God, faith, and morality [32]. According to a Swedish study [33], the most frequently posed questions by palliative cancer patients to the hospital chaplain were of a general existential nature concerned with meaning-related issues and with death and dying. The authors suggest that the low prevalence (8%) of explicit religious concerns is a consequence of low religious belief and practice in a secular society. However, general existential problems seem to be of great importance to cancer patients across cultures and regardless of faith inclinations as demonstrated by an American study concluding that the ten most intense demands of colorectal cancer patients were predominately psychosocial and existential [34].

The results showing that 8% of patients indicate a need for help and support in relation to their spiritual/religious concerns highlight that cancer rehabilitation interventions should include systematic attention to the spiritual/religious and existential aspects of survivorship. Thus, they point to the importance of a broader appreciation of and attention to spiritual/religious concerns across the cancer trajectory and of developing interventions that might meet these concerns.

Age

In our sample, the experience of spiritual/religious concerns was most intense for the young cancer patients, and our first hypothesis was not supported. Thus, it seems that the situation is entirely different when we are in a setting of suffering and crisis than the normal progress of healthy life. In this context, the younger a person is when falling ill with cancer, the more meaningless it appears. When being a young parent, known to draw meaning in life from one’s children and parenthood, being struck by cancer makes life unbearably meaningless.

An interpretation could be that the replies were given in a context of illness and suffering. One should remember again that the question in the Dallund Scale did not concern personal beliefs but the experience of spiritual/religious concerns. It could be that the young are more open to life and cannot fathom non-existence or death as they are in the middle of their adult life. Or it could be that they to a higher degree are propelled to believe, in order to find meaning in an often frightening and meaningless situation of suffering, at life’s zenith. It may also be that the young have had less time than the elderly to come to terms with their own beliefs and sources of meaning. In a study by Fitchett [35], a similar difference between young and old cancer patients was found. Fitchett argued that the young people are more shocked by suffering earlier in life as “some forms of religious development or maturity come with age and protect older people against religious struggles”. As a general tendency, young cancer patients experience more religious struggles than older cancer patients [17, 35], something found in transplant survivors as well [36], whereas the older cancer patients experience higher levels of spiritual well-being as measured for instance with the FACIT-SP [37].

Obviously, one cannot rule out the possibility that the young in this sample actually are more religious than older people, and that this is why they report more spiritual/religious concerns. However, this is not consistent with general research literature documenting that young people in secular societies are much less religious than older people [38]. Furthermore, given that all types of reported spiritual/religious concerns are higher for the young people, this suggests that it is their level of concern (including guilt and existence) that is higher rather than their religiosity. This makes the unexpected finding of a higher degree of spiritual/religious concerns among the young in our sample of even higher clinical relevance, as it may suggest that the young are not prepared for navigating spiritual crises.

Gender

In line with others, we find more spiritual/religious concerns in women compared to men reflecting the general tendency that women are more religious than men for various reasons [14]. Men are likewise known to be less active in health-seeking behavior than women and less likely than women to want to discuss their ailments with other patients [39]. Several barriers may explain this tendency, such as avoiding disclosure of their illness as it does not correspond to “traditional masculine behavior”: man’s perceived social role in society, a sense of immunity, difficulty relinquishing control, a feeling that asking for help is unacceptable, etc. [40]. Thus, it was a challenge for RcDallund to recruit men to the courses (the normal gender distribution at RcDallund patient courses was around 86% women, see Fig. 1). The men that did enroll at these courses may have had similar characteristics to women, both in terms of health-seeking behavior and spiritual/religious concerns as behaviors and characteristics might overlap [14]. Second, it might also be that the men who did enroll at RcDallund did so because they had more spiritual/religious concerns than most male patients and that taking action in relation to these concerns was their motivation behind enrolling.

Emotional problems

The study shows a clear association between emotional problems such as hopelessness, depression, and anxiety and the spiritual/religious concerns that we address in this article. Those most struck mentally by their cancer disease are those who report most unmet spiritual/religious concerns. Hopelessness in particular predicts concerns of a spiritual/religious nature, in particular with regard to the existential dimension. The findings are consistent with vast bodies of research that suggest that spirituality and religiousness are powerful sources of hope when other sources of hope seem to fail [41], and hence, it is only natural that hopelessness propels spiritual/religious seeking. Thus, the saying “Faith moves mountains” is as true as its opposite–that mountains of disease and suffering seem to move faith [42]. This is true in particular for very secular nations where the most widespread type of religiosity is often described as “crisis religiosity” [43]. Similarly important is the strong association that we found between emotional problems in the sample and the experienced need for help. Such need for help obviously calls for action.

Strengths and limitations

The most important strength of this study is the large sample size (6400 respondents) and the high response rate (100%). Regarding limitations, the fact that the Dallund Scale was developed to serve both clinical purposes (assessing problems and concerns of cancer survivors attending the rehabilitation course so that the staff could target the rehabilitation interventions) as well as research purposes entails challenges. The fact that the Dallund Scale has not been developed primarily for research purposes means that it lacks scientific rigor (e.g., validation) and contains conceptual inconsistencies. For example, the battery “spiritual/religious concerns” seems to contain a mismatch between concepts in that one of the items (“in relation to existence”) can be chosen without intending a reference to spiritual/religious concerns. It is likewise possible that many more respondents would have reported having concerns of guilt/existence etc. if it had not been categorized under the “spiritual/religious concerns” battery. Assessment of spiritual/religious concerns presupposes both considerations on how conceptual constructs are understood and shaped by contextual factors as well as precise and explicit descriptions of how the concepts are employed in specific research contexts. The Dallund scale does not assess spirituality or religiosity per se, which also means that the interpretation of the age and gender effect is limited. We have dealt with conceptual discussions and scrutinization elsewhere [44]. For the purpose of this study, it suffices to specify that in line with an Anglo-Saxon understanding of “spirituality,” the construct spiritual/religious is understood to potentially encompass both a broad non-religious and a narrower religious sense of meaning and purpose in life. As the construct is employed in the Dallund scale, essential shared dimensions, such as faith, morality, guilt and existence, link the concepts spirituality and religion/religiosity as important existential domains [44]. Furthermore, it should be underlined that the study is cross-sectional and not longitudinal with the methodological challenges this entails.

Practical relevance and implications for research

Although Denmark is considered the least religious nation in the world, our study shows that many cancer survivors enrolled at RcDallund experienced various spiritual/religious concerns and existential problems. This holds particularly true for the concerns related to guilt and to existence. The findings of this study suggest that rehabilitation professionals must be attentive to the concerns reported in this study, even in a secular culture where spiritual/religious and existential issues are often considered taboo and private. Barriers are widely reported among health professionals in relation to communication about spiritual/religious and existential issues. Some of these barriers relate to factors such as lack of time, lack of training, fear of crossing professional boundaries, and experienced power inequities with patients [45], even in palliative settings [46].

The challenges of how to overcome such barriers might be addressed optimally in a systemic approach to multi-dimensional rehabilitation programs where the entire team is able to identify and address such concerns and needs through training and continued learning but also through the presence of spiritual/religious/existential care specialists such as chaplains. Such optimization requires competent knowledge of best practice care, which in turn calls for further research in this complex field. The results of such research may continue to inform the targeted development of existentially and spiritually oriented approaches to support individuals with cancer.

References

Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E (2006) From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in transition. National Academies Press

Henoch I, Danielson E (2008) Existential concerns among patients with cancer and interventions to meet them: an integrative literature review. Psycho-Oncology. 18(3):225–236

Assing Hvidt E (2015) The existential cancer journey: travelling through the intersubjective structure of homeworld/alienworld. Health. 21:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459315617312

Park CL (2012) Meaning making in cancer survivorship. In: Wong PTP (ed) The human quest for meaning. Theories, research and applications, 2nd edn. Routledge, New York

Breitbart W (2002) Spirituality and meaning in supportive care: spirituality- and meaning-centered group psychotherapy interventions in advanced Cancer. Support Care Cancer 10(4):272–280

Kristeller JL, Rhodes M, Cripe LD, Sheets V (2005) Oncologist assisted spiritual intervention study (OASIS): patient acceptability and initial evidence of effects. Int J Psychiatry Med 35(4):329–347

Zuckerman P (2008) Society without God : what the least religious nations can tell us about contentment. New York University Press, New York

Gundelach P (2011) Små og store forandringer danskernes værdier siden 1981. Hans Reitzels Forlag, Copenhagen

Rosen I (2009) I'm a believer - but I'll be damned if I’m religious. In: Belief and religion in the Greater Copenhagen area - a focus group study. Lund studies in Sociology of Religion. Lunds Universitet

Assing Hvidt E, Iversen HR, Hansen HP (2013) “Someone to hold the hand over me”: the significance of transpersonal “attachment” relationships of Danish cancer survivors. Eur J Cancer Care 22(6):726–737

Assing Hvidt E (2013) Sources of ‘relational homes’ - a qualitative study of cancer survivors’ perceptions of emotional support. Ment Health Relig Cult 16(6):617–632

Johannessen-Henry CT, Deltour I, Bidstrup PE, Dalton SO, Johansen C (2013) Associations between faith, distress and mental adjustment – a Danish survivorship study. Acta Oncol 52(2):364–371. https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186X.2012.744141

Hvidtjorn D, Hjelmborg J, Skytthe A, Christensen K, Hvidt NC (2014) Religiousness and religious coping in a secular society: the gender perspective. J Relig Health 53(5):1329–1341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-013-9724-z

Trzebiatowska M, Bruce S (2012) Why are women more religious than men? 1st edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Dein S, Cook CC, Koenig H (2012) Religion, spirituality, and mental health: current controversies and future directions. J Nerv Ment Dis 200(10):852–855. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e31826b6dle

World Health Organization. International classification of functioning disability and health (ICF). 2001. http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/. Accessed 23.10.13 2013.

Manning-Walsh J (2005) Spiritual struggle: effect on quality of life and life satisfaction in women with breast cancer. J Holist Nurs 23(2):120–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898010104272019

Pargament KI, Desai KM, McConnell KM (2006) Spirituality: a pathway to posttraumatic growth or decline? In: Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG (eds) Handbook of posttraumatic growth : research and practice. Mahwah, N.J. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp 121–137

Fitchett G, Risk JL (2009) Screening for spiritual struggle. J Pastoral Care Counsel 63(1–2):4–1-12

Hansen H, Tjørnhøj-Thomsen T (2008) Cancer rehabilitation in Denmark: the growth of a new narrative. Med Anthropol Q 22(4):360–380

Tjørnhøj-Thomsen T, Hansen HP (2013) The ritualization of rehabilitation. Med Anthropol 32(3):266–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/01459740.2011.637255

Roth AJ, Kornblith AB, Batel-Copel L, Peabody E, Scher HI, Holland JC (1998) Rapid screening for psychologic distress in men with prostate carcinoma. Cancer 82(10):1904–1908. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19980515)82:10<1904::AID-CNCR13>3.0.CO;2-X

Donovan KA, Grassi L, McGinty HL, Jacobsen PB (2014) Validation of the distress thermometer worldwide: state of the science. Psycho-Oncology. 23(3):241–250. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3430

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). NCCN distress thermometer and problem list. 2018. https://www.nccn.org/about/permissions/thermometer.aspx. Accessed 04 Nov 2018.

Kristensen T. Dallundskalaen. [Visitation of cancer patients to a rehabilitation, Project anno 2004] Visitation af kræftpatienter til rehabilitering, projekt årgang 2004. Søndersø: RehabiliteringsCenter Dallund2005.

Kristensen T, Hjortebjerg U, Larsen S, Mark K, Tofte J, Piester CB (2004) Rehabilitation after Cancer: 30 statements evaluated by more than 1.000 patients. Psycho-Oncology. 13:178 (poster)

Armstrong RA (2014) When to use the Bonferroni correction. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 34(5):502–508. https://doi.org/10.1111/opo.12131.

Strang P (1997) Existential consequences of unrelieved cancer pain. Palliat Med 11:299–305

Hansen HP, Tjornhoj-Thomsen T, Johansen C (2011) Rehabilitation interventions for cancer survivors: the influence of context. Acta Oncol 50(2):259–264. https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186X.2010.529460

Rosedale M (2009) Survivor loneliness of women following breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 36(2):175–183

Assing Hvidt E, Iversen HR, Hansen HP (2012) Belief and meaning orientations among Danish cancer patients in rehabilitation. A Taylorian perspective. Spiritual Care 1(3):1–22

la Cour P (2008) Existential and religious issues when admitted to hospital in a secular society: patterns of change. Ment Health Relig Cult 11(8):769–782

Strang S, Strang P, Ternestedt BM (2002) Spiritual needs as defined by Swedish nursing staff. J Clin Nurs 11(1):48–57. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2702.2002.00569.x

Klemm P, Miller MA, Fernsler J (2000) Demands of illness in people treated for colorectal cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 27(4):633–639

Fitchett G, Murphy PE, Kim J, Gibbons JL, Cameron JR, Davis JA (2004) Religious struggle - prevalence, correlates and mental health risks in diabetic, congestive heart failure, and oncology patients. Int J Psychiatry Med 34(2):179–196

King SD, Fitchett G, Murphy PE, Pargament KI, Martin PJ, Johnson RH, Harrison DA, Loggers ET (2017) Spiritual or religious struggle in hematopoietic cell transplant survivors. Psycho-Oncology. 26(2):270–277

Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady MJ, Hernandez L, Cella D (2002) Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-spiritual well-being scale (FACIT-Sp). Ann Behav Med 24(1):49–58

Crockett A, Voas D (2006) Generations of decline: religious change in 20th-century britain. J Sci Study Relig 45(4):567–584

Galdas PM, Cheater F, Marshall P (2005) Men and health help-seeking behaviour: literature review. J Adv Nurs 49(6):616–623. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03331.x

Eakin EG, Strycker LA (2001) Awareness and barriers to use of cancer support and information resources by HMO patients with breast, prostate, or colon cancer: patient and provider perspectives. Psychooncology. 10(2):103–113

Koenig HG (1994) Religion and hope. Religion in aging and health: theoretical foundations and methodological frontiers, pp 18–51

Hvidt NC, Hvidtjørn D, Christensen K, Nielsen JB, Sondergaard J (2016) Faith moves mountains-mountains move faith: two opposite epidemiological forces in research on religion and health. J Relig Health 56:294–304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-016-0300-1

Ahrenfeldt LJ, Möller S, Andersen-Ranberg K, Vitved AR, Lindahl-Jacobsen R, Hvidt NC (2017) Religiousness and health in Europe. Eur J Epidemiol 32(10):921–929. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-017-0296-1

la Cour P, Hvidt NC (2010) Research on meaning-making and health in secular society: secular, spiritual and religious existential orientations. Soc Sci Med 71(7):1292–1299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.06.024

Assing Hvidt E, Søndergaard J, Gulbrandsen P, Ammentorp J, Timmermann C, Hvidt NC (2018) ‘We are the barriers’: Danish general practitioners’ interpretations of why the existential and spiritual dimensions are neglected in patient care. Commun Med 14(2):108–120. https://doi.org/10.1558/cam.32147

Balboni MJ, Sullivan A, Enzinger AC, Epstein-Peterson ZD, Tseng YD, Mitchell C et al. Nurse and Physician Barriers to Spiritual Care Provision at the End of Life. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.09.020

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the Danish Cancer Society for the many decades they have financed the Rehabilitation Centre Dallund, where all data of this study was collected, and to thank all the cancer survivors who participated in the study. We also wish to thank Tom Kristensen who developed the Dallund scale.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hvidt, N.C., Mikkelsen, T.B., Zwisler, A.D. et al. Spiritual, religious, and existential concerns of cancer survivors in a secular country with focus on age, gender, and emotional challenges. Support Care Cancer 27, 4713–4721 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04775-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04775-4