Abstract

Purpose

This study examined relationships between sedentary behavior accumulated in different bout durations and quality of life (QoL) among breast cancer survivors.

Methods

Postmenopausal breast cancer survivors completed the Short Form Health Survey to assess QoL and wore an accelerometer to measure sedentary behavior and physical activity between August 2011 and May 2013.

Results

Participants (n = 134) averaged 509.7 min/day in sedentary time with 285.2 min/day in short bouts (<20 min) and 224.5 min/day long bouts (≥20 min). Linear regression models indicated that greater total sedentary time was significantly associated with worse physical QoL (b = −0.70, p = 0.02) but not mental QoL (p = 0.92). Models that examined the accumulation of sedentary time in short bouts and long bouts together showed that time in long sedentary bouts was significantly related to physical QoL (b = −0.72, p = 0.02), while time in short bouts was not (p = 0.63). Moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity (MVPA) was a significant effect modifier of the relation between time spent in long sedentary bouts and physical QoL (p = 0.028) such that greater time in long bouts was associated with worse physical QoL only among women with lower levels of MVPA.

Conclusions

Findings indicate that time spent in long sedentary bouts is associated with worse physical QoL among breast cancer survivors who do not engage in high levels of MVPA. Future research should examine reducing sedentary time as a potential strategy to improve physical QoL.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Breast cancer and its treatments can have a significant and potentially long-term negative impact on a woman’s quality of life (QoL) [1]. Increasing physical activity has been shown in several reviews and meta-analyses to improve a variety of physical and psychosocial health outcomes, including QoL [2–4]. However, much less is known about the impact of sedentary behavior on QoL outcomes, especially among breast cancer survivors. Sedentary behavior refers to any sitting or reclining activities that do not increase energy expenditure substantially above the resting level [5] such as watching TV, reading a book, working on a computer, or driving in your car. Research indicates that cancer survivors spend about two thirds of their day in sedentary behaviors such as sitting and reclining [6–8]. Poor health-related quality of life has been shown to reduce time to breast cancer recurrence and all-cause mortality among breast cancer survivors [9]. Therefore, understanding the relationship between sedentary time and QoL among breast cancer patients is an important first step in determining if changing sedentary time could be a potential intervention target to improve breast cancer-related outcomes.

A limited number of published studies have examined the relationships between sedentary behavior and QoL in breast cancer survivors, and findings from these studies have been mixed. For example, George et al. found that sedentary time was not associated with health-related QoL among 710 breast cancer survivors [10]. Conversely, Phillips et al. found that greater sedentary time was associated with worse fatigue and physical well-being among 358 survivors [6]. Explanations for these discrepant findings may relate to differences in measures used to assess both QoL and sedentary time. Evidence in non-cancer populations suggests that the relationship between sedentary behavior and QoL varies based on the aspect of QoL that is measured. Specifically, data suggests that sedentary behavior is more strongly associated with physical QoL than mental QoL [11, 12]. Similarly, studies with concurrent self-reported and objective measures of sedentary behavior have shown that relationships between sedentary behavior and health outcomes vary depending on the measurement tool used to assess sedentary behavior [11, 13, 14].

An emerging area of sedentary behavior research suggests that the way in which sedentary time is accumulated (e.g., in long uninterrupted vs. short bouts) can also influence the effect of sedentary behavior on health outcomes. Extended periods of uninterrupted sedentary time may have a different impact on QoL and other outcomes than shorter bouts. Although we are not aware of published studies that have compared the relationship of sedentary bout lengths on QoL outcomes in breast cancer survivors, there is growing evidence in non-cancer populations that prolonged unbroken bouts of sedentary behaviors (e.g., 20 to 30 min in duration) have a particularly negative impact on a number of metabolic risk factors [15]. Interestingly, breaking up sedentary time has been shown to be positively associated with health outcomes [16–19]. Taken together, these findings highlight the importance of partitioning time spent in sedentary behavior into different bout lengths when examining relationships between sedentary behavior and health outcomes.

Research in non-cancer populations has shown that the benefits of engaging in physical activity, including those done at moderate-to-vigorous intensity, may not reduce negative impacts associated with prolonged sitting [20]. One reason for the mixed findings for the relationship of moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity (MVPA) and sedentary behavior on health may be due to the conceptual/statistical treatment of MVPA. Many early studies included MVPA as a covariate in their models to assess “independent” associations between sedentary behavior and health, effectively treating it as a confounder [21]. Emerging evidence suggests that MVPA is most likely a moderator (a.k.a. effect modifier) whereby greater sedentary time is associated with increased mortality risk and worse physical functioning only among adults with low levels of MVPA [20, 22–24]. However, a recent meta-analysis in non-cancer populations found that increasing time spent in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) did not result in large decreases in sedentary time [25]. Therefore, it is important to examine the relationship of these two distinct behaviors, MVPA and sedentary time, with quality of life.

The primary objective of the present study was to investigate the relationships between objectively measured sedentary time and the accumulation of sedentary time in short bouts (<20 min) and long bouts (≥20 min), with physical and mental QoL among breast cancer survivors. We hypothesized that total sedentary time would be inversely associated with QoL among women with a history of breast cancer. We also hypothesized that greater time in long sedentary bouts, but not short bouts, would be associated with worse QoL. Given the evidence that the relationship of sedentary behavior and QOL may not be independent of MVPA [10, 26], we additionally adjusted all models for time spent in MVPA and examined whether MVPA modified the relationship between sedentary time and QoL. These analyses can provide a better understanding of sedentary behavior and QoL, which can inform lifestyle interventions to improve QoL among women with a history of breast cancer.

Methods

Study design and sample

Participants were postmenopausal breast cancer survivors from the UC San Diego Transdisciplinary Research in Energetics and Cancer (TREC) center. The TREC center was a program project examining the role of insulin resistance and inflammation in breast cancer risk [27]. Ninety-six overweight and obese women (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) were recruited for the Reach for Health Study, a randomized trial examining the impact of metformin and weight loss interventions on breast cancer mortality [28]. The baseline data used for this analysis were obtained prior to randomization into the intervention. An additional 40 lean women (BMI < 25 kg/m2) were recruited specifically to enrich the Reach for Health Study sample by concurrently collecting data on women with BMI < 25 kg/m2 for investigations of lifestyle factors and health outcomes across the BMI continuum. Recruitment of participants was conducted simultaneously by means of flyers at community events, physician referral, and use of cancer patient registries, and assessments were conducted with the same measures and clinical space. In addition, the same study staff and protocols were used for both groups. There were no significant differences between the two groups in regard to age, race, education, or stage of breast cancer (p > 0.05).

Eligibility was assessed via a telephone interview. Eligible participants were diagnosed with primary operable breast carcinoma (stages I-III) within the past 5 years, were postmenopausal at the time of breast cancer diagnosis, and were not scheduled for or currently undergoing chemotherapy. Women were excluded if they had been diagnosed with any additional primary or recurrent invasive cancer within the last 10 years or had a serious medical condition such as renal insufficiency, liver impairment, or congestive heart failure. Participants were also excluded if they were diabetic or using hormone replacement therapy.

Of the 1157 women who were contacted, 166 were eligible and 134 completed all relevant study assessments. The most frequent reasons for ineligibility were not being postmenopausal at diagnosis and diagnosed more than 5 years ago. All participants attended an in-person study visit where they completed a series of physical measurements and study questionnaires. After the clinic visit, participants were provided a hip-worn accelerometer to wear for 7 days. The UC San Diego institutional review board approved all study procedures, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Measures

Objective assessment of physical activity and sedentary behavior

The ActiGraph GT3X+ accelerometer (ActiGraph, Pensecola, FL), which records integrated acceleration information as an activity “count,” provides an objective estimate of the movement and intensity of activity. The ActiGraph is widely used in the field of physical activity and sedentary behavior research and has good validation with VO2 max [29]. Participants were asked to wear the accelerometer on their right hip during waking hours for 7 days and to take it off for swimming or bathing. A 7-day wear period was selected to ensure collection of at least 3–5 valid days of data, which is the number of days of data recommended for reliably estimating behavioral patterns [30, 31]. ActiLife v6.3.4 software was used to screen for sufficient wear time using the guidelines for accelerometry-derived physical activity data outlined by Choi et al. [32]. Sufficient wear time was defined as 5 days with ≥600 min of wear time or 3000 min (50 h) across 4 days. A total of four participants had incomplete accelerometer data and were asked to re-wear the device for the number of missing days. All complete and valid data were processed in ActiLife using the low-frequency extension and aggregated to 60-s epochs so activity and sedentary cut points could be applied [33].

We relied on established cut points to classify sedentary behaviors from accelerometer data. As such, a threshold of 100 counts/min on the x-axis defined sedentary activities [34]. Time spent per day in sedentary activities was calculated by summing the minutes in a day where the counts were below 100 counts/min. We averaged day level totals across measurement days for each participant to yield the average daily time spent sedentary. Bouts of sedentary time were identified as consecutive minutes of sedentary time; each bout was given a unique identifier. For each day, the number of minutes accumulated in bouts between 1 and 19 min in duration (“short bouts”) was computed, as was the number of minutes spent in bouts of at least 20 min in duration (“long bouts”). Long bouts were operationalized as any bout with a duration greater than or equal to 20 min as this duration has shown to adversely affect health in epidemiologic [35] and experimental [18] studies. The average daily minutes in short and long bouts were then computed for each person. To determine time spent in MVPA (activity at three METs or higher, e.g., brisk walk or faster), established cut points for accelerometer data was used by summing every minute in a day where the x-axis counts were 1952 or above [33]. Day level averages for time spent in MVPA were then computed for each participant.

Quality of life

QoL was assessed using the Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) [36]. The questionnaire has been used in diverse populations, including women with breast cancer [37], and has shown to be reliable (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.75 to 0.91) [38] with good construct validity [39]. The SF-36 provides physical and mental health component summary scores that range from 0 to 100, with higher scores corresponding to better QoL.

Other assessments

Height and weight were measured at baseline clinic visits using standard protocols and used to calculate body mass index (BMI, kg/m2). Medical records were reviewed to ascertain information related to breast cancer diagnosis and treatment, including date of diagnosis, disease stage, type of breast surgery, chemotherapy (any vs. no chemotherapy), and use of endocrine therapy.

Statistical methods

Participant characteristics, QoL, and sedentary behavior variables were presented as mean (SDs) or (n%). Relationships between time in short bouts, time in long bouts, total sedentary time, and time spent in moderate-to-vigorous physical activities were examined with partial correlations between each accelerometer-derived measure, controlling for accelerometer wear time.

In multivariable linear regression models, we examined associations between accelerometer-derived time spent in sedentary behavior and QoL outcomes. The sedentary behavior variables were modeled in 30-min increments (instead of 1-min increments) in order to make the parameter estimates more interpretable. Physical and mental health component summary scores were examined separately. We also partitioned total sedentary time into time spent in <20 min bouts and time spent in ≥20 min bouts. Multivariable linear regression models were used to model QoL outcomes by including time in short sedentary bouts and time in long bouts in the same model [40]. The base models controlled for continuous age and BMI, cancer stage (dichotomous: stage I vs. stages II and III), and accelerometer wear time. Subsequent models also adjusted for time spent in total MVPA, given the well-documented associations between time spent in MVPA and QoL in both healthy and diseased populations [6, 41–43]. We considered adjustment for other breast cancer variables that may influence the association between the exposures of interest and QoL outcomes (e.g., time since diagnosis, chemotherapy, radiation, and use of endocrine therapy); however, the addition of these variables did not meaningfully influence the magnitude or statistical significance of the findings we report. Therefore, we left these additional breast cancer-related variables out of final models.

Interaction models were used to formally test whether observed relationships between minutes per day in sedentary behavior and physical health scores varied by time spent in total MVPA. Interaction models controlled for the same covariates as models described above (i.e., age, BMI, cancer stage, accelerometer wear time, and short sedentary bouts) in addition to the main effects of minutes per day in sedentary behavior and total MVPA and the sedentary behavior × total MVPA interaction term (both modeled as continuous variables). Main interaction models were run with un-centered variables, but we tested the consistency of our findings in models with mean-centered variables. Subsample analyses were used to explore the nature of effect modification by stratifying models according to whether or not women engaged in at least 30 min/day of total MVPA, which is consistent with public health recommendations for physical activity. Sensitivity analyses were also run with MVPA in bouts of at least 10 min, the minimum duration of MVPA recommended by the physical activity guidelines [44, 45].

For all final models, variance inflation factors (VIFs) were computed to test for multicollinearity; all VIFs were <2 indicating multicollinearity was not an issue. Statistical analyses were conducted in SAS 9.4 and SAS Studio (Cary, NC), as well as R version 3.1.3. All statistical tests were two sided, and alpha was set at 0.05.

Results

One hundred and thirty-four breast cancer survivors completed the QoL assessment and had accelerometer data collected. As shown in Table 1, the average age of participants was 63 years. Total sedentary time averaged 509.7 min/day with 285.2 min/day in short bouts and 224.5 min/day in long bouts.

There were statistically significant correlations between several of the accelerometry-derived activity and sedentary behavior variables. After controlling for accelerometer wear time, total sedentary time was significantly associated with time in long bouts (r = 0.84) but not with time in short bouts. Total minutes per day of MVPA was significantly inversely correlated with total sedentary time (r = −0.39) and time in long bouts (r = −0.25), but was not significantly correlated with time in short bouts. Time in short sedentary bouts was only significantly correlated with time in long bouts (r = −0.51) (data not shown).

In multivariable linear regression models, total minutes per day of sedentary time was significantly associated with physical health after adjustment for age, BMI, cancer stage, and total accelerometer wear time (Table 2). Specifically, results of base models indicate that each 30-min/day increase in sedentary time was associated with a 0.70-U decrease in the physical health summary score (p = 0.02). However, this association between sedentary time and physical health was not significant in MVPA-adjusted models.

Table 3 presents models of the associations between time spent in long and short bouts of sedentary behavior with physical and mental health summary scores. There was a statistically significant association between minutes per day spent in long bouts of sedentary time with the physical health summary score after adjustment for time in short sedentary bouts, age, BMI, cancer stage, and total accelerometer wear time. Results indicate that each 30-min/day increase in total time spent in long sedentary bouts was associated with a 0.72-U decrease in physical health scores (p = 0.02), when not controlling for time spent in MVPA. Adjustment for time spent in total MVPA attenuated associations between time spent in long sedentary bouts and physical health to non-significance (b = −0.49, p = 0.13). It is notable that time spent in total MVPA was a significant independent predictor of physical health scores (b = 0.10, p = 0.046). Time spent in short sedentary bouts was not significantly associated with physical health in the base or MVPA-adjusted models (p > 0.05). None of the sedentary behavior exposure variables were related to the mental health summary score (p > 0.05).

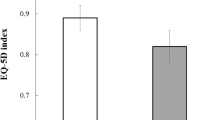

We formally tested time spent in MVPA as an effect modifier of the relationship between sedentary behavior and physical health scores. We found no evidence of effect modification by MVPA for the association between total sedentary time and QoL. However, there was a statistically significant interaction between time spent in long sedentary bouts and time spent in MVPA (both modeled as continuous variables; p = 0.04). Accordingly, we stratified the analysis by levels of time spent in MVPA (<30 vs. ≥30 min/day MVPA) and examined associations between time spent in long sedentary bouts and physical health scores within each MVPA strata. We observed that each 30-min/day increase in time spent in long sedentary bouts was inversely associated with physical health scores among women who engaged in less than 30 min/day of MVPA (b = −0.78, p = 0.04). However, time in long bouts was not associated with physical QoL among women who engaged in 30 or more minutes of MVPA per day (b = 0.18, p = 0.76) (Fig. 1). We also conducted a sensitivity analysis with MVPA in bouts of at least 10 min in length and MVPA remained as an effect modifier (p = 0.04, data not shown).

Associations between long sedentary bouts (>20 min in duration) and physical QoL, stratified by women who engaged in <30 min/day MVPA (n = 99) vs. ≥30 min/day MVPA (n = 35). Models used least squares means approach to adjust for time in short sedentary bouts, stage, age, BMI, and accelerometer wear time. Data were collected between August 2011 and May 2013. *p = 0.05. MVPA = moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity

Conclusions

The purpose of this study was to examine associations between objectively measured sedentary time with QoL among survivors of early stage breast cancer. A novel aspect of this analysis was the focus on investigating the effects of sedentary time when accumulated in long vs. short bouts. Our results indicate that overall sedentary time was related to worse physical health, and this association appeared to be driven by time spent in longer sedentary bouts (here measured as ≥20 min in duration). MVPA moderated the associations between sedentary behavior and physical health, with the strongest relationship found among women with low amount of time spent in total MVPA (here measured as <30 min/day). This could have public health implications as decreasing sedentary time may be an important and achievable behavioral target to improve quality of life for the many breast cancer survivors who are not meeting physical activity guidelines [46, 47].

Results are consistent with the one published study we found that examined long sedentary bouts with mental QoL [48]. Specifically, Vallance and colleagues found no significant associations between objectively measured in long sedentary bouts and aspects of mental QoL among colon cancer survivors [48]. However, our findings that time spent in sedentary behavior was only associated with physical health scores among women with low levels of physical activity is in contrast to a study by George et al. [49], who found that the associations between sedentary behaviors, as measured by an inclinometer, were independent of time spent in MVPA. These conflicting findings may suggest that the impact of sedentary time varies by cancer type. Alternatively, conflicting findings may be due to the fact that different measures were used to assess sedentary behavior and QoL across studies. Research on sedentary time and QoL is still an emerging field where consistency in measures could be critical for advancing knowledge and identifying individuals who might benefit from reducing sedentary time.

Our finding that long bouts of sedentary time were driving the relationship between sedentary time and the physical health among women who do not engage in high amounts of MVPA could have important implications for tailored behavioral recommendations and intervention targets. For example, these data suggest that interventions designed to “break up” long bouts of sedentary time (i.e., via standing breaks) may be an important strategy to improve QoL among breast cancer survivors who do not regularly exercise. However, such an intervention may not be effective at improving QoL among breast cancer survivors who engage in high levels of physical activity.

One possibility for the lack of association between sedentary time and mental QoL is that the context in which the sedentary activities occurs may be important. For example, engaging in stimulating sedentary behaviors, such as reading or having coffee with friends, may increase mental QoL and thereby attenuate the relationship between sedentary time and metal QoL. While objective measures of sedentary time may reduce recall bias of the measurement [50], they often do not provide information on the context in which sedentary behavior occurs. Future research should examine types of sedentary behaviors to identify if some behaviors are more detrimental for QoL in cancer survivors than others.

Strengths of this study include the use of objective methods to identify sedentary behaviors, which are less prone to recall and response biases than traditional self-report approaches [50]. However, it should be noted that the hip-worn accelerometer x-axis counts per minute cut point used to define sedentary behavior in the current study is not able to differentiate between standing still and seated postures [50]. Therefore, it is possible that we have miss-classified standing still as a sedentary behavior. Future studies using devices with inclinometers may be able to more accurately distinguish between seated and standing postures [51]. In addition, new computational methods using raw data from the three accelerometer axes are being developed to better characterize sedentary time from accelerometer data, which could be used in future studies to reduce measurement errors [50]. Given the cross-sectional nature of the data collected, we also cannot rule out the possibility of reverse causality between sedentary behavior and physical health summary scores (e.g., women are sedentary as a result of poor physical health). Generalizability of these results may be limited as our sample was predominately diagnosed at stage I, white, and highly educated patients.

In summary, the results of the present study demonstrate that greater sedentary time accumulated in bouts longer than 20 min in duration is associated with worse physical health among women with low levels of physical activity. Relationships of sedentary time with mental health were not uncovered, even using the more discriminating long bouts. To our knowledge, this was the first study to examine associations between objectively measured sedentary behavior of different bout lengths and QoL outcomes in breast cancer survivors. Future longitudinal studies should investigate whether introducing interruptions in sedentary time improves QoL among inactive breast cancer survivors.

References

Chopra I, Kamal KM (2012) A systematic review of quality of life instruments in long-term breast cancer survivors. Health Qual Life Outcomes 10:14

Mishra SI, Scherer RW, Geigle PM, Berlanstein DR, Topaloglu O, Gotay CC, Snyder C (2012) Exercise interventions on health-related quality of life for cancer survivors. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 8:CD007566. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007566.pub2

Duijts SF, Faber MM, Oldenburg HS, van Beurden M, Aaronson NK (2011) Effectiveness of behavioral techniques and physical exercise on psychosocial functioning and health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients and survivors—a meta-analysis. Psycho-Oncology 20:115–126

Fong DY, Ho JW, Hui BP, Lee AM, Macfarlane DJ, Leung SS, Cerin E, Chan WY, Leung IP, Lam SH, Taylor AJ, Cheng KK (2012) Physical activity for cancer survivors: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 344:e70

Sedentary Behaviour Research N (2012) Letter to the editor: standardized use of the terms “sedentary” and “sedentary behaviours”. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 37:540–542

Phillips SM, Awick EA, Conroy DE, Pellegrini CA, Mailey EL, McAuley E (2015) Objectively measured physical activity and sedentary behavior and quality of life indicators in survivors of breast cancer. Cancer 121:4044–4052

Boyle T, Vallance JK, Ransom EK, Lynch BM (2016) How sedentary and physically active are breast cancer survivors, and which population subgroups have higher or lower levels of these behaviors?. Support Care Cancer 24:2181-90

Trinh L, Amireault S, Lacombe J, Sabiston CM (2015) Physical and psychological health among breast cancer survivors: interactions with sedentary behavior and physical activity. Psycho-Oncology 24:1279–1285

Saquib N, Pierce JP, Saquib J, Flatt SW, Natarajan L, Bardwell WA, Patterson RE, Stefanick ML, Thomson CA, Rock CL, Jones LA, Gold EB, Karanja N, Parker BA (2011) Poor physical health predicts time to additional breast cancer events and mortality in breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology 20:252–259

George SM, Alfano CM, Wilder Smith A, Irwin ML, McTiernan A, Bernstein L, Baumgartner KB, Ballard-Barbash R (2013) Sedentary behavior, health-related quality of life, and fatigue among breast cancer survivors. J Phys Act Health 10:350–358

Rosenberg DE, Bellettiere J, Gardiner PA, Villarreal VN, Crist K, Kerr J (2016) Independent associations between sedentary behaviors and mental, cognitive, physical, and functional health among older adults in retirement communities. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 71:78–83

Kim J, Im JS, Choi YH (2016) Objectively measured sedentary behavior and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity on the health-related quality of life in US adults: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003-2006. Qual Life Res. doi:10.1007/s11136-016-1451-y

Stamatakis E, Davis M, Stathi A, Hamer M (2012) Associations between multiple indicators of objectively-measured and self-reported sedentary behaviour and cardiometabolic risk in older adults. Prev Med 54:82–87

Celis-Morales CA, Perez-Bravo F, Ibanez L, Salas C, Bailey ME, Gill JM (2012) Objective vs. self-reported physical activity and sedentary time: effects of measurement method on relationships with risk biomarkers. PLoS One 7:e36345

Lyden K, Keadle SK, Staudenmayer J, Braun B, Freedson PS (2015) Discrete features of sedentary behavior impact cardiometabolic risk factors. Med Sci Sports Exerc 47:1079–1086

Sardinha LB, Santos DA, Silva AM, Baptista F, Owen N (2015) Breaking-up sedentary time is associated with physical function in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 70:119–124

Davis MG, Fox KR, Stathi A, Trayers T, Thompson JL, Cooper AR (2014) Objectively measured sedentary time and its association with physical function in older adults. J Aging Phys Act 22:474–481

Dunstan DW, Kingwell BA, Larsen R, Healy GN, Cerin E, Hamilton MT, Shaw JE, Bertovic DA, Zimmet PZ, Salmon J, Owen N (2012) Breaking up prolonged sitting reduces postprandial glucose and insulin responses. Diabetes Care 35:976–983

Peddie MC, Bone JL, Rehrer NJ, Skeaff CM, Gray AR, Perry TL (2013) Breaking prolonged sitting reduces postprandial glycemia in healthy, normal-weight adults: a randomized crossover trial. Am J Clin Nutr 98:358–366

Gennuso KP, Gangnon RE, Matthews CE, Thraen-Borowski KM, Colbert LH (2013) Sedentary behavior, physical activity, and markers of health in older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc 45:1493–1500

Ford ES, Caspersen CJ (2012) Sedentary behaviour and cardiovascular disease: a review of prospective studies. Int J Epidemiol 41:1338–1353

Matthews CE, Keadle SK, Troiano RP, Kahle L, Koster A, Brychta R, Van Domelen D, Caserotti P, Chen KY, Harris TB, Berrigan D (2016) Accelerometer-measured dose-response for physical activity, sedentary time, and mortality in US adults. Am J Clin Nutr 104:1424–1432

Ekelund U, Steene-Johannessen J, Brown WJ, Fagerland MW, Owen N, Powell KE, Bauman A, Lee IM, Lancet Physical Activity Series 2 Executive C, Lancet Sedentary Behaviour Working G (2016) Does physical activity attenuate, or even eliminate, the detrimental association of sitting time with mortality? A harmonised meta-analysis of data from more than 1 million men and women. Lancet 388:1302–1310

Seguin R, Lamonte M, Tinker L, Liu J, Woods N, Michael YL, Bushnell C, Lacroix AZ (2012) Sedentary behavior and physical function decline in older women: findings from the Women’s Health Initiative. J Aging Res 2012:271589

Prince SA, Saunders TJ, Gresty K, Reid RD (2014) A comparison of the effectiveness of physical activity and sedentary behaviour interventions in reducing sedentary time in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials. Obes Rev 15:905–919

Loprinzi PD (2015) Joint associations of objectively-measured sedentary behavior and physical activity with health-related quality of life. Prev Med Rep 2:959–961

Patterson RE, Colditz GA, Hu FB, Schmitz KH, Ahima RS, Brownson RC, Carson KR, Chavarro JE, Chodosh LA, Gehlert S, Gill J, Glanz K, Haire-Joshu D, Herbst KL, Hoehner CM, Hovmand PS, Irwin ML, Jacobs LA, James AS, Jones LW, Kerr J, Kibel AS, King IB, Ligibel JA, Meyerhardt JA, Natarajan L, Neuhouser ML, Olefsky JM, Proctor EK, Redline S, Rock CL, Rosner B, Sarwer DB, Schwartz JS, Sears DD, Sesso HD, Stampfer MJ, Subramanian SV, Taveras EM, Tchou J, Thompson B, Troxel AB, Wessling-Resnick M, Wolin KY, Thornquist MD (2013) The 2011-2016 Transdisciplinary Research on Energetics and Cancer (TREC) initiative: rationale and design. Cancer Causes Control 24:695–704

Patterson RE, Marinac CR, Natarajan L, Hartman SJ, Cadmus-Bertram L, Flatt SW, Li H, Parker B, Oratowski-Coleman J, Villasenor A, Godbole S, Kerr J (2016) Recruitment strategies, design, and participant characteristics in a trial of weight-loss and metformin in breast cancer survivors. Contemp Clin Trials 47:64–71

Kelly LA, McMillan DG, Anderson A, Fippinger M, Fillerup G, Rider J (2013) Validity of actigraphs uniaxial and triaxial accelerometers for assessment of physical activity in adults in laboratory conditions. BMC Med Phys 13:5

Trost SG, McIver KL, Pate RR (2005) Conducting accelerometer-based activity assessments in field-based research. Med Sci Sports Exerc 37:S531–S543

Ward DS, Evenson KR, Vaughn A, Rodgers AB, Troiano RP (2005) Accelerometer use in physical activity: best practices and research recommendations. Med Sci Sports Exerc 37:S582–S588

Choi L, Liu Z, Matthews CE, Buchowski MS (2011) Validation of accelerometer wear and nonwear time classification algorithm. Med Sci Sports Exerc 43:357–364

Freedson PS, Melanson E, Sirard J (1998) Calibration of the Computer Science and Applications, Inc. accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc 30:777–781

Matthews CE, Chen KY, Freedson PS, Buchowski MS, Beech BM, Pate RR, Troiano RP (2008) Amount of time spent in sedentary behaviors in the United States, 2003-2004. Am J Epidemiol 167:875–881

Carson V, Wong SL, Winkler E, Healy GN, Colley RC, Tremblay MS (2014) Patterns of sedentary time and cardiometabolic risk among Canadian adults. Prev Med 65:23–27

Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD (1992) The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 30:473–483

Goodwin PJ, Black JT, Bordeleau LJ, Ganz PA (2003) Health-related quality-of-life measurement in randomized clinical trials in breast cancer—taking stock. J Natl Cancer Inst 95:263–281

Kosinski M, Keller SD, Hatoum HT, Kong SX, Ware JE Jr (1999) The SF-36 Health Survey as a generic outcome measure in clinical trials of patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: tests of data quality, scaling assumptions and score reliability. Med Care 37:MS10–MS22

Ware JE Jr, Gandek B (1998) Overview of the SF-36 Health Survey and the International Quality of Life Assessment (IQOLA) project. J Clin Epidemiol 51:903–912

Mekary RA, Willett WC, Hu FB, Ding EL (2009) Isotemporal substitution paradigm for physical activity epidemiology and weight change. Am J Epidemiol 170:519–527

Vallance JK, Boyle T, Courneya KS, Lynch BM (2014) Associations of objectively assessed physical activity and sedentary time with health-related quality of life among colon cancer survivors. Cancer 120:2919–2926

Perales F, del Pozo-Cruz J, del Pozo-Cruz J, del Pozo-Cruz B (2014) On the associations between physical activity and quality of life: findings from an Australian nationally representative panel survey. Qual Life Res 23:1921–1933

Halaweh H, Willen C, Grimby-Ekman A, Svantesson U (2015) Physical activity and health-related quality of life among community dwelling elderly. Journal of Clinical Medicine Research 7:845–852

United States. Department of Health and Human Services. (2008) 2008 physical activity guidelines for Americans: be active, healthy, and happy! U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Washington

Schmitz KH, Courneya KS, Matthews C, Demark-Wahnefried W, Galvao DA, Pinto BM, Irwin ML, Wolin KY, Segal RJ, Lucia A, Schneider CM, von Gruenigen VE, Schwartz AL, American College of Sports M (2010) American College of Sports Medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc 42:1409–1426

Hair BY, Hayes S, Tse CK, Bell MB, Olshan AF (2014) Racial differences in physical activity among breast cancer survivors: implications for breast cancer care. Cancer 120:2174–2182

Harrison S, Hayes SC, Newman B (2009) Level of physical activity and characteristics associated with change following breast cancer diagnosis and treatment. Psychooncology 18:387–394

Vallance JK, Boyle T, Courneya KS, Lynch BM (2015) Accelerometer-assessed physical activity and sedentary time among colon cancer survivors: associations with psychological health outcomes. Journal of Cancer Survivorship: Research and Practice 9:404–411

George SM, Alfano CM, Groves J, Karabulut Z, Haman KL, Murphy BA, Matthews CE (2014) Objectively measured sedentary time is related to quality of life among cancer survivors. PLoS One 9:e87937

Atkin AJ, Gorely T, Clemes SA, Yates T, Edwardson C, Brage S, Salmon J, Marshall SJ, Biddle SJ (2012) Methods of measurement in epidemiology: sedentary behaviour. Int J Epidemiol 41:1460–1471

Lyden K, Kozey Keadle SL, Staudenmayer JW, Freedson PS (2012) Validity of two wearable monitors to estimate breaks from sedentary time. Med Sci Sports Exerc 44:2243–2252

Acknowledgements

Research support was provided by funding from the National Cancer Institute (U54CA155435). Dr. Hartman was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K07CA181323; Dr. Marinac was supported under Award Number F31CA183125. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The UC San Diego institutional review board approved all study procedures, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hartman, S.J., Marinac, C.R., Bellettiere, J. et al. Objectively measured sedentary behavior and quality of life among survivors of early stage breast cancer. Support Care Cancer 25, 2495–2503 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3657-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3657-0