Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this review is to update the MASCC (Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer) guidelines for controlling nausea and vomiting with chemotherapy of low or minimal emetic potential.

Methods

The antiemetic study group of MASCC met in Copenhagen in 2015 to review the MASCC antiemetic guidelines. A subgroup performed a systematic literature review on antiemetics for low emetogenic chemotherapy (LEC) and chemotherapy of minimal emetic potential and the chair presented the update recommendation to the whole group for discussion. They then voted with an aim of achieving 67 % or greater consensus.

Results

For patients receiving low emetogenic chemotherapy, a single antiemetic such as dexamethasone, a 5HT3 receptor antagonist, or a dopamine receptor antagonist may be considered for prophylaxis of acute emesis. For patients receiving chemotherapy of minimal emetogenicity, no antiemetic should be routinely administered. If patients vomit, they should be treated as for chemotherapy of low emetic potential. No antiemetic should be administered for prevention of delayed nausea and vomiting induced by low or minimally emetogenic chemotherapy.

Conclusions

More research is needed to determine the incidence of emesis, particularly delayed emesis, in the LEC group. Prospective studies are required to evaluate antiemetic strategies. The risk of emesis within LEC may be more accurately determined by adding the patient risk factors for emesis to those of the chemotherapy drugs. Improved strategies for promoting adherence to guidelines are required.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The proportion of patients expected to experience nausea and vomiting if they received no antiemetic prior to treatment with anticancer drugs is the basis for characterising their emetic potential. Drugs of low emetic potential are those where the risk of emesis lies between 10 and 30 %. With drugs of minimal emetic potential the risk is <10 % [1, 2]. The dose, schedule, and route of administration will all impact on the emetogenicity of the agent.

Many of the newer targeted therapies fit into the category of agents of low or minimal emetic potential, necessitating regular updates to the classification [3]. Often there is a lack of data to accurately classify them and rarely are there trials specifically to document the emetic toxicity of a drug.

Nausea and vomiting in patients receiving drugs of low or minimal emetic potential may be due to causes other than the chemotherapy, such as gastritis, peptic ulceration, bowel obstruction, or metabolic abnormalities which should be excluded from history and examination.

Methods

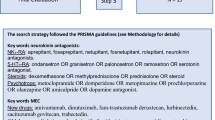

Committees were formed to work on each section of the guideline prior to a meeting in June 2015 in Copenhagen. A systematic review of the literature was performed.

In Copenhagen, each committee chair presented the findings of that committee to the entire MASCC antiemetic group and included the suggested rating of the level of evidence/confidence of the guideline. After the discussion, the group voted on the changes suggested. For consensus, 67 % or greater agreement was required. To change a guideline, well-conducted trials with appropriate comparators representing best practice were required to show at least a 10 % difference to the previous recommendation.

Results

The results of the systematic review:

For updating the antiemetic guidelines, a search of antiemetics/chemotherapy-induced guidelines included papers published from 6/2009 to 5/2015. The electronic databases of MEDLINE (via Pub med) and CENTRAL yielded 667 records. Five of them were focused on nausea and vomiting and chemotherapy of low or minimal emetic potential, including the MASCC guideline recommendations from 2011. Additionally, and in cooperation with Committee I, the new agents proposed as of low and minimal emetogenic risk were scanned.

A well-established drug such as trastuzumab has had its emetic potential initially determined in early phase trials [4]. A subsequent study specifically explored the gastrointestinal toxicity of trastuzumab and suggested that nausea and vomiting occurred in <10 % [5].

Pembrolizumab, one of the more recent targeted therapies, although originally classed as of minimal emetic potential is reported in its product information from early studies to be associated with up to 30 % nausea and 16 % vomiting, but in a later study in melanoma, vomiting was reported as 11.2 % which would make it of low emetic potential but more data is needed [6, 7].

Many oral chemotherapy drugs have a paucity of data about their emetogenicity. An exception is oral etoposide, when used for refractory testicular cancer, which showed it to be low emetogenic chemotherapy, LEC [8]. It is interesting to note that although it was of low and not minimal emetic potential, the authors did not recommend prophylactic antiemetics as the potential for emesis was at the lower end of the range, around 11 %. Only 2 of 16 patients subsequently required antiemetics.

There is often less evidence about the ideal antiemetic prophylaxis for chemotherapy of low emetic potential [9]. Guidelines to date have been written with high levels of expert consensus but low levels of evidence. The recommendations for LEC have been to use single agents. The ASCO (American Society of Clinical Oncology) guidelines recommend using single agent steroids, most commonly dexamethasone [10]. The NCCN (National Comprehensive Cancer Network) suggests that single agents could include dexamethasone, metoclopramide, or prochlorperazine [11]. A potential drawback of using dexamethasone is its side effects and it is contraindicated with some agents such as ipilimumab. More studied in moderately emetogenic chemotherapy (MEC), side effects include insomnia, agitation, depression gastrointestinal symptom dyspepsia, hyperglycaemia, hypertension, and rashes [12, 13]. Appetite stimulation and weight gain may be an advantage in some cases but can also be problematic. It is also unclear what the optimal dose is. The guidelines differ, but in MEC, 8 mg dexamethasone has been found to be effective and has acceptable toxicity [13].

Adding a second agent in LEC may improve outcomes. Costa et al., in reviewing the use of antiemetics to prevent nausea and vomiting due to oral chemotherapy, included domperidone and metoclopramide and suggested the possibility of adding lorazepam [14]. However, another study of adding ondansetron to dexamethasone with the LEC, docetaxel, was not able to demonstrate greater efficacy over the single agent [15].

Since the last MASCC publication of guidelines for the control of nausea and vomiting with chemotherapy of low or minimal emetic potential, there has been a prospective cohort study examining the efficacy of single agent granisetron when used a primary prophylaxis with LEC [16]. In the study, patients could receive dexamethasone or metoclopramide before MEC but one group received IV granisetron as well. There was a higher complete response (no emesis and no use of rescue antiemetics) rate in the acute phase (0–24 h after chemotherapy) in the group who received granisetron but no difference in acute nausea or delayed (24–120 h after chemotherapy) nausea and vomiting. This limited response calls into question how cost effective 5HT3 receptor antagonists are for LEC.

No guidelines have recommended routine antiemetic prophylaxis against delayed emesis for LEC. However, Fabi et al. report that after antiemetic prophylaxis 6 % of LEC patients still have acute emesis but 22.8 % have delayed emesis [17]. Molassiotis et al. reported that a group of patients receiving LEC had increasing delayed emesis from cycle 1 to cycle 4, the incidence increasing from 25 to 50 % [18]. Maybe choosing dexamethasone or even metoclopramide as the single agent may provide protection against delayed emesis, particularly when used on multiple days with oral chemotherapy. Palonosetron, a longer acting 5-HT3 receptor antagonist is indicated for the control of both acute and delayed emesis in highly emetogenic chemotherapy (HEC) and MEC [19–21]. Schwartzberg et al. performed a retrospective analysis on patients receiving LEC and also noted that delayed nausea and vomiting was the major contributor to overall nausea and vomiting in patients receiving single day LEC. In MEC and HEC, comparing those who had received palonosetron against those who received other 5-HT3 receptor antagonists, there were significantly lower nausea and vomiting rates after palonosetron [22]. Palonosetron may have more impact on delayed emesis.

Palonosetron has also proven effective in patients who had incomplete control of nausea and vomiting, with at least moderate nausea after a prior cycle of LEC. No vomiting occurred in 91.2 % in the acute phase and 79.4 % of patients during delayed phase, with no nausea in 73.5 and 52.9 %, respectively [23]. It would be desirable to follow these results with a randomised study of using palonosetron as a single agent prior to LEC. It is noted that as with MEC and HEC nausea is not as well controlled in LEC as vomiting.

Olanzapine has not been trialed in LEC but has shown promise as an alternative to NK1 RA’s in combination antiemetic regimens [24].

The lack of definitive studies on the emetogenicity of some drugs classified as LEC and the paucity of prospective use of antiemetic studies in this group results in guidelines that are more consensus than evidence-based and indicates the need for more research in this group.

Recommendations

Prevention of acute nausea and vomiting in patients receiving low emetogenic chemotherapy

A single antiemetic agent, such as dexamethasone, a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, or a dopamine receptor antagonist, such as metoclopramide, may be considered for prophylaxis in patients receiving chemotherapy of low emetic risk*.

-

MASCC Level of Confidence: Low

-

MASCC Level of Consensus: Moderate

-

ESMO Level of Evidence: II

-

ESMO Grade of Recommendation: B

*Dexamethasone can be used except if contraindicated, e.g., with agents such as ipilimumab.

Prevention of acute nausea and vomiting in patients receiving minimally emetogenic chemotherapy*

No antiemetic should be routinely administered before chemotherapy to patients without a history of nausea and vomiting.

-

MASCC Level of Confidence: No Confidence Possible

-

MASCC Level of Consensus: High

-

ESMO Level of Evidence: IV

-

ESMO Grade of Recommendation: D

*While unusual at this emetic level, if a patient experiences nausea or vomiting, it is advised that, with subsequent chemotherapy treatments, the regimen for the next higher emetic level be given.

Prevention of delayed nausea and vomiting in patients receiving low or minimally emetogenic chemotherapy*

No antiemetic should be administered for prevention of delayed nausea and vomiting induced by low or minimally emetogenic chemotherapy.

-

MASCC Level of Confidence: No Confidence Possible

-

MASCC Level of Consensus: High

-

ESMO Level of Evidence: IV

-

ESMO Grade of Recommendation: D

*While unusual at this emetic level, if a patient experiences nausea or vomiting, it is advised that, with subsequent chemotherapy treatments, the regimen for the next higher emetic level be given.

Discussion

The major change in the LEC guidelines from that published in 2010, is a softening of the guideline for recommending a single agent antiemetic for agents of low emetic potential from, “is suggested” to “may be considered.” The reason is not only the lack of evidence but also that LEC spans from chemotherapy with a 10 to 30 % risk of causing emesis. The need for prophylactic antiemetics is likely to be vastly different at the upper end of that range compared to the lower. Also, the choice of antiemetic may depend on the anticancer drugs, since drugs such as the taxanes are given with a premedication of dexamethasone, and also, dexamethasone is contraindicated with agents such as ipilimumab where it would abrogate the therapeutic effects of the CTLA-4 antibody.

Could we better predict the likelihood of nausea and vomiting? We could add patient-related factors which contribute to the risk of nausea and vomiting [25]. We have known that younger patients have more emesis than older and that females have more nausea and vomiting than males [26]. People with a history of high alcohol intake are less likely to vomit than those with a low intake [27]. A past history of vomiting due to motion sickness or morning sickness with pregnancy makes it more likely that there will be vomiting post chemotherapy [26, 28]. Likewise vomiting with previous chemotherapy increases the risk of vomiting with subsequent chemotherapy, but even the expectation of nausea is associated with experiencing nausea post chemotherapy [29]. If we added these factors to the known emetic potential of the chemotherapy, we should have a more accurate assessment of the risk of nausea and vomiting prior to chemotherapy. However, to date there is not a validated model to predict the emetic potential of chemotherapy when adding patient factors to intrinsic chemotherapy risk.

Even when guidelines are based on high levels of evidence, there is no guarantee that they will be translated into clinical practice, despite the fact that adherence to guidelines has been shown to result in better antiemetic outcomes [25, 30]. Recent studies of antiemetic use in SE Asia show variable patterns of adherence to guidelines, reflecting the situation in Europe [31]. The uptake of guidelines is a subject for further research in its own right. A recent pilot study explored the creation of education modules with guidelines so their content can be the subject of continuing education programs [32].

In revising the guidelines for LEC, it is apparent that further research is needed in to using multiple risk factors to determine the emetic potential of low and minimally emetic drugs. We need to more precisely define the incidence of emesis for new drugs, particularly in the delayed phase, to refine who needs prophylactic antiemetics and then perform prospective antiemetic studies.

References

Hesketh PJ, Kris KG, Grunberg SM, et al. (1997) Proposal for classifying the acute emetogenicity of cancer chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 15:103–109

Grunberg SM, Osaba D, Hesketh PJ et al (2005) Evaluation of new antiemetic agents and definition of antineoplastic emetogenicity—an update. Support Care Cancer 13:80–84

http://www.mascc.org/antiemetic-guidelines Last accessed 27th Feb 2016

Perry CM, Wiseman LR (1999) Trastuzumab. BioDrugs 12(2):129–135

Al-Dasooqi N, Boen JM, Gibson RJ, et al. (2009) Trastuzumab induces gastrointestinal side effects in HER2-overexpresssing breast cancer patients. Investig New Drugs 27:173–178

http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/125514lbl.pdf Last accessed 27th February 2016

Robert C, Schachter J, Long GV, et al. (2015) Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. New Engl J Med 372:2521–2532

Einhorn LH, Brames MJ (2006) Emetic potential of daily oral etoposide. Support Care Cancer 14:1262–1265

Tonato M, Clark-Snow RA, Osoba D, et al. (2005) Emesis induced by low or minimal emetogenic risk chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 13:109–111

Basch E, Hesketh PJ, Kris MJ, et al. (2011) Antiemetics: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Oncol Practice 7:395–398

https://www.nccn.org/store/login/login.aspx?ReturnURL=http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/antiemesis.pdf. Last accessed 17th Feb 2016

Vardy J, Chiew KS, Galica J, et al. (2006) Side effects associated with the use of dexamethasone for prophylaxis of delayed emesis after moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. Br J Cancer 94:1011–1015

Italian group for antiemetic research (2004) Randomised double-blind, dose-finding study of dexamethasone in preventing acute emesis induced by anthracyclines, carboplatin, or cyclophosphamide. J Clin Oncol 22:752–729

Costa AL, Abreu C, Pacheo TR et al (2015) Prevention of nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing oral anticancer therapies for solid tumours. Biomed Res Int. Article ID 309601. doi: 10.1155/2015/309601

Hayashi T, Ikesue H, Esaki T, et al. (2010) Implementation of institutional antiemetic guidelines for low emetic risk chemotherapy with docetaxel: a clinical and cost evaluation. Support Care Cancer 20:1805–1810

Keat CH, Phua G, Kassim MSA, et al. (2013) Can granisetron injection used as a primary prophylaxis improve the control of nausea and vomiting with low-emetogenic chemotherapy? Asia Pacific J Cancer Prev 14:469–473

Fabi A, Barduagni M, Lauro S, et al. (2011) Is delayed chemotherapy-induced emesis well managed in oncological clinical practice? An observational study. Support Care Cancer 11:156–161

Molassiotis A, Saunders MP, Valle J, et al. (2008) A prospective observational study of chemotherapy-related nausea and vomiting in routine practice in a UK cancer centre. Support Care Cancer 16:201–208

Gralla R, Lichinitser M, Van Der Vegt S, et al. (2003) Palonosetron improves prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting following moderately emetogenic chemotherapy: results of a double-blind randomized phase III trial comparing single doses of palonosetron with ondansetron. Ann Oncol 14:1570–1577

Saito M, Aogi K, Sekine I, et al. (2009) Palonosetron plus dexamethasone versus granisetron plus dexamethasone for prevention of nausea and vomiting during chemotherapy: a double-blind, double-dummy, randomised, comparative phase III trial. Lancet Oncol 10:115–124

Aapro MS, Grunberg SM, Manikhas GM, et al. (2006) A phase III, double-blind, randomized trial of palonosetron compared with ondansetron in preventing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting following highly emetogenic chemotherapy. Ann Oncol 17:1441–1449

Schwartzberg L, Morrow G, Balu S, et al. (2011) Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting and antiemetic prophylaxis with palonosetron versus other 5HT3 receptor antagonists in patients with cancer treated with low emetogenic chemotherapy in a hospital outpatient setting in the United States. Curr Med Res Opin 27:1613–1622

Hesketh PJ, Morrow G, Komorowski AW, Ahmed R, Cox D (2012) Efficacy and safety of palonosetron as salvage treatment in the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients receiving low emetogenic chemotherapy (LEC). Support Care Cancer 20:2633–2637

Navari RM, Gray SE, Kerr AC (2011) Olanzapine versus aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a randomised phase II trial. J Support Oncol 9:188–195

Jordan K, Jahn F, Aapro M (2015) Recent developments in the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV): a comprehensive review. Ann Oncol 26:1091–1090

Warr DG, Street JC, Carides AD (2011) Evaluation of risk factors predictive of nausea and vomiting with current standard-of-care antiemetic treatment: analysis of phase 3 trial of aprepitant in patients receiving adriamycin-cyclophosphamide-based chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 19:807–813

D’Acqusito RW, Tyson LB, Gralla RJ, et al. (1986) The influence of chromic high alcohol intake on chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 5:257

Morrow GR (1985) The effect of susceptibility to motion sickness on the side effects of cancer chemotherapy. Cancer 55:2766–2770

Olver IN, Taylor AE, Whitford H (2005) Relationships between patients’ pre-treatment expectations of toxicities and post chemotherapy experiences. Psycho-Oncology 14:25–33

Aapro M, Molassiotis A, Dicato M, et al. (2012) The effect of guideline-consistent antiemetic therapy on chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV): the Pan European Emesis Registry (PEER). Ann Oncol 23:1986–1992

Yu S, Burke TA, Chan A, et al. (2014) Antiemetic therapy in Asia Pacific countries for patients receiving moderately and highly emetogenic chemotherapy—a descriptive analysis of practice patterns, antiemetic quality of care, and use of antiemetic guidelines. Support Care Cancer 23:273–282

Olver I, von Dincklage J, Nicholson J, Shaw T (2016) Improving uptake of wiki-based guidelines with Qstream education. Med Educ 50:590–591

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors received remuneration, research funding, and consultancies as follows:

I Olver: Tesaro; C Ruhlmann: Swedish Orphan Biovitrum; F Jahn: MSD, Merck, Helsinn, Tesaro; L Schwartzberg: Eisai, Merck, Helsinn, Tesaro; B Rapoport: Merck, Helsinn, MSD Tesaro; C Rittenberg: none; R Clark-Snow: none.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Olver, I., Ruhlmann, C.H., Jahn, F. et al. 2016 Updated MASCC/ESMO Consensus Recommendations: Controlling nausea and vomiting with chemotherapy of low or minimal emetic potential. Support Care Cancer 25, 297–301 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3391-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3391-z