Abstract

Purpose

Fatigue is one of the most common and bothersome refractory symptoms experienced by cancer survivors. Mindful exercise interventions such as yoga improve cancer-related fatigue; however, studies of yoga have included heterogeneous survivorship populations, and the effect of yoga on fatigued survivors remains unclear.

Methods

We randomly assigned 34 early-stage breast cancer survivors with cancer-related fatigue (≥4 on a Likert scale from 1–10) within 1 year from diagnosis to a 12-week intervention of home-based yoga versus strengthening exercises, both presented on a DVD. The primary endpoints were feasibility and changes in fatigue, as measured by the Multidimensional Fatigue Symptom Inventory-Short Form (MFSI-SF). Secondary endpoint was quality of life, assessed by the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapies-Breast (FACT-B).

Results

We invited 401 women to participate in the study; 78 responded, and we enrolled 34. Both groups had significant within-group improvement in multiple domains of the fatigue and quality of life scores from baseline to post-intervention, and these benefits were maintained at 3 months post-intervention. However, there was no significant difference between groups in fatigue or quality of life at any assessment time. Similarly, there was no difference between groups in adherence to the exercise intervention.

Conclusions

Both DVD-based yoga and strengthening exercises designed for cancer survivors may be good options to address fatigue in breast cancer survivors. Both have reasonable uptake, are convenient and reproducible, and may be helpful in decreasing fatigue and improving quality of life in the first year post-diagnosis in breast cancer patients with cancer-related fatigue.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There are currently more than 14.5 million cancer survivors in the USA [1]. Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women, with more than 3.3 million survivors [2]. The persistent adverse effects of cancer and its treatment have become increasingly appreciated, making supportive care to address persistent symptoms a priority in oncology.

Cancer-related fatigue (CRF), in particular, has emerged as a uniquely bothersome and prevalent symptom among cancer survivors, occurring in 80 % of patients [3]. In breast cancer survivors, CRF persists beyond 4 months from diagnosis in 33 % [4] and beyond 5 years in 21 % of patients [5]. There are no validated pharmaceutical treatments for CRF. Activity enhancement has grade A evidence, per National Comprehensive Care Network (NCCN) guidelines, as an effective CRF treatment, yet little is known regarding the relative benefits of different types of exercise in ameliorating CRF [6].

Physical exercise has been shown to positively impact multiple domains: fatigue [7, 8], overall quality of life (QOL) [9, 10], physical fitness [11], and lymphedema [12, 13] in breast cancer survivors. In addition, exercise interventions are associated with decreased breast cancer recurrence and mortality in observational studies [14, 15].

Cancer survivors in general, breast cancer survivors in particular, express great interest in complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) methods, for coping with the side effects of treatment and the distress caused by a cancer diagnosis [16]. Less is known about alternative, mindfulness-based modalities of physical exercise, such as Pilates, Yoga, and Tai-chi in this population; there are many programs and classes available for the general population and aggressively promoted as effective methods of rehabilitation after breast cancer treatment, despite limited evidence of safety or benefit [17]. Recent guidelines by the Society for Integrative Medicine, based on a systematic review of the CAM interventions for symptom relief in breast cancer survivors, recommend yoga as an intervention for anxiety and mood disorders (grade A recommendation), and for stress reduction, depression, fatigue, and decreased QOL (grade B recommendation) [18].

Yoga has been increasingly studied in cancer survivors for its effects on QOL, fatigue, mood, vasomotor symptoms, physical function, chemotherapy-induced nausea, depression, stress, and spiritual well-being [19–23] with varying results. A few well-conducted, randomized, controlled studies of yoga demonstrated improvements in CRF after breast cancer treatments [4, 24–26]. One of these studies [4] exploring an Iyengar yoga intervention delivered twice weekly for 12 weeks, in 90-min sessions, versus health education, in 31 post-menopausal women with early stage breast cancer experiencing persistent fatigue, demonstrated significant improvements in fatigue, vitality, and vigor in the yoga group compared with the health education group. Similar findings resulted from a larger study (N = 163) of stage 0–3 breast cancer survivors undergoing radiation therapy, in which a Patanjali-based yoga intervention (60-min sessions three times a week for the 6 weeks duration or radiotherapy) was shown to be similar to a stretching intervention concerning improvement in fatigue at the end of the radiation treatments and superior to the stretching and waitlist groups regarding the QOL outcomes at 1, 3, and 6 months post-radiation. However, only one of these studies solely recruited patients with CRF, and most did not have an active control group.

To address these caveats in study design, our study selected only patients who reported CRF, and the randomization was to two active intervention groups: yoga versus strengthening exercises. Moreover, we wanted to explore the feasibility of an intervention that would be inexpensive, reproducible, and easily available, thus we have chosen a home-based intervention through a DVD. This would allow participants free choice of timing of the exercise routine, removing the need for transportation to a studio and the hassles of schedule coordination with a class intervention. One such study of DVD-based exercise intervention in patients with metastatic colon and lung cancer has shown a high adherence rate of 77 % and improvements in QOL, fatigue, and mobility [27].

The primary aim of our pilot study was to assess the feasibility and effect on CRF and QOL of a yoga intervention in breast cancer survivors experiencing CRF. We hypothesized that yoga is superior to strengthening exercises in improving CRF and QOL in this population. The findings should provide the basis for developing an evidence-based exercise prescription for this population as part of a larger goal of providing holistic, individualized, patient-oriented breast cancer survivorship care.

Methods

Study design and oversight

Our pilot study addresses the feasibility of 12 weeks of DVD-guided, home-based, Hatha yoga versus a strengthening intervention in breast cancer survivors with CRF and the impact of these interventions on CRF and QOL.

Participants

Inclusion criteria were female patients with CRF, between 20–75 years of age, diagnosed with stage 0–2 breast cancer, being between 4–12 months post-surgery and at least 2 months post-radiation and/or chemotherapy (to exclude patients with short-term radiation or chemotherapy-related fatigue). CRF was defined as a score of ≥4 on a single numeric analog scale from 0–10 regarding the level of fatigue they are experiencing, per NCCN guidelines (moderate fatigue score 4–6; severe fatigue score 7–10) [28]. We excluded those who performed mindfulness-based or strengthening exercises on a regular basis (more than once weekly) and those without a DVD player in their homes. The participants were instructed to avoid practicing exercise routines other than the intervention they were randomized to, for the duration of the study. This was discussed at the time of the consent visit and re-enforced during the bi-weekly phone calls

Potential participants were identified through Mayo Clinic’s electronic medical record, through providers’ referral, and recruitment flyers. An initial recruitment letter was sent to prospective participants, and a second reminder letter was sent to non-responders. Interested participants were screened for eligibility, and those eligible were enrolled after obtaining written informed consent. The study was approved by Mayo Clinic’s Institutional Review Board (IRB). Consented participants were assigned through computer randomization software to one of the two study groups and stratified by age into 20–50-year-old and 51–75-year-old groups to control for age as a confounding factor.

Outcomes

Feasibility and safety were assessed through recruitment, retention and attrition rates, and through adherence to the exercise prescription. Adherence was assessed both through patient charting and a phone call every 2 weeks by study personnel. Compliance to the intervention was defined as practicing the intervention three or more times/week, for seven or more of the 12-week study. Side effects were assessed during the bi-monthly phone calls or were self-reported by the patient at any time, and the study team used a consensus process to decide whether or not the reported effects were related to the intervention.

Fatigue was evaluated through the Multidimensional Fatigue Symptom Inventory-Short Form (MFSI-SF). The MFSI is a reliable and valid measure of fatigue that was designed for use with cancer patients [29–32]. The MFSI-SF consists of 30 statements designed to assess the multi-dimensional nature of fatigue. Responders indicate to what extent they experienced each symptom during the preceding week (0 = not at all; 4 = extremely). Ratings were summed to obtain scores on five subscales (general fatigue, physical fatigue, emotional fatigue, mental fatigue, and vigor). Note that the fatigue scale used for eligibility purposes (Likert scale 0–10) was different than the tool used for assessment of CRF (MFSI-SF).

Quality of life was assessed through the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapies, Breast (FACT-B). The FACT-B is a multi-dimensional QOL questionnaire developed for breast cancer patients [33]; it has excellent validity and reliability properties in breast cancer patients [34, 35]. Higher scores correlate with the desirability of the outcome. It includes the domains of physical, social, emotional, and functional well-being and a subscale of additional concerns specific to breast cancer patients. Summation of the scores in these five domains results in the FACT-B total score.

Clinically rather than statistically significant differences in QOL, denoted as minimally important differences (MIDs), were available and validated for four scores generated by the FACT-B: Breast Cancer Subscale (2–3 points), Trial Outcomes Index (5–6 points), FACT-G total (5–6 points), and FACT-B total (7–8 points) [36].

Intervention

Participants completed the outcome questionnaires at baseline, post-intervention (12 weeks), and at 3 months post-intervention. The questionnaires were handed to the patients during the baseline and the 3-month post-intervention visits and returned either by mail or in-person, while the post-intervention (12 weeks) questionnaires were mailed-out in a pre-paid, self-addressed envelope. Up to two reminder phone calls were made if the questionnaires were not returned. The baseline visit included a PowerPoint presentation outlining the intervention. Throughout the 12 weeks of intervention, the subjects were asked to keep a log of daily adherence to the program. Bi-monthly phone calls were made to assess and document adherence and side effects and to encourage compliance with the intervention.

After randomization, the participants were provided with DVDs containing the yoga intervention or the strengthening exercises, respectively, for use at home. The strengthening group also received a package of progressive resistance strengthening bands color-coded by resistance level. It was recommended that they perform the exercises contained in the DVD at least 3×/week, and up to 5×/week. The DVD-type intervention was chosen to increase the convenience and potentially the adherence to the intervention. Because there is no established routine rehabilitation intervention after cancer treatments, strengthening exercises were chosen for our study due to the availability of this intervention on a DVD at our institution, which has been offered to cancer survivors. Selecting a strengthening intervention also allowed a comparison between the effects of a mindfulness- versus a non-mindfulness-based physical exercise on CRF.

The yoga DVD contains the following sections: an introduction to the practice and philosophy of the yoga exercise developed by a certified yoga therapist specialized in treating patients with cancer, Parkinson’s, and cardiac diseases http://www.exclusiveyoga.com/dvd.php), followed by sections on relaxed breathing (geared toward softening the body and calming the mind), warm-up (exercises for all the muscles and joints aimed to decrease fatigue), soft yoga (improving flexibility and decreasing anxiety), seated sun salutation (energizes the body and enhances positive mindset), standing yoga (increases strength and builds self-confidence), chair stretches (to release muscle tension and invite inner focus), and guided relaxation (to aid in the healing process and restore emotional equilibrium). The DVD runs for approximately 90 min. Written instructions on the yoga DVD content was provided to the participants.

The strengthening DVD called Rapid Easy Strength Training (REST) was created at Mayo Clinic by a team from the Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation department. The DVD instructs viewers in sets of five upper and five lower body exercises; each set requires roughly 10 min to complete, for a total of 20 min of intervention. The exercises target upper and lower extremities as well as core muscles with resistance provided by elastic bands. The DVD encourages the isometric recruitment of core muscles during all exercises and provides targeted instruction. Use of the DVD, in combination with gentle aerobic conditioning, has been shown to improve CRF in two randomized, controlled trials that enrolled patients with advanced stage cancers [27, 37]. Written instructions on the content of the DVDs were provided. A description of the two interventions used in this study is presented in Table 1.

Statistical methods

Participant characteristics and scores (fatigue, QOL) were summarized with frequencies and percentages or means and standard deviations, as appropriate. The scores were calculated at each follow-up assessment, and differences in scores were calculated as follow-up minus baseline score. A last observation carried forward (LOCF) approach was employed for participants who did not complete follow-up assessments. This approach conservatively assumes no additional change from the previous time point. Categorical data at baseline was compared with chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate. Comparisons of scores within each study group were assessed with paired t tests, and comparisons of baseline scores as well as change from baseline were assessed with two-sample t tests assuming unequal variances. The comparison of the average change from baseline between the yoga and strength-training groups was summarized with 95 % confidence intervals. Minimally important differences (MIDs) were identified based on the mean change from baseline. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

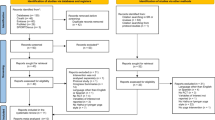

We sent out initial invitation letters to 401 potentially eligible participants identified through Mayo Clinic’s electronic medical system. Seventy-eight patients responded to our invitation to participate, representing a 19.5 % response rate. Figure 1 depicts a CONSORT diagram of the recruitment, retention, and adverse events. All of the responders had a DVD player in their household.

A total of 34 patients were enrolled between December 2012 and October 2013, 16 in the strengthening exercises and 18 in the yoga group. There was no difference between the baseline characteristics of the groups regarding age (median 63 and 61, respectively), education level, marital status, fatigue and QOL scores, exercise levels, stage of the disease, and treatment received. Table 2 summarizes the baseline characteristics of the two groups.

Of the 34 participants, 23 (68 %) completed the 12-week intervention based on their adherence logs. Study completion rate was 74 % in the yoga group and 54 % in the strengthening group. The reasons for early termination of the study for 11 participants are summarized in the figure.

Table 3 describes the compliance with the intervention (defined as exercising more than 3×/week for 7 weeks or more) for the two groups; 44 % were compliant with the strengthening intervention (median number of compliant weeks = 5.0) and 39 % in the yoga group (median = 4.5), with no statistically significant difference between the groups. Taking the yoga group and the strengthening group together, the changes in CRF and QOL outcomes were similar between the participants who were compliant and those who were non-compliant, from baseline to post-intervention, except for a significant difference in improvement in the functional domain of the QOL (median improvement of 1.0 vs 3.6 points for non-compliant vs compliant, P = 0.005) and a trend toward improvement in the vigor subscale of the CRF (P = 0.07) in favor of those who were compliant (median improvement of 1.4 vs 4.1; see Table 4). Further analysis of the compliant versus non-compliant participants within groups and between groups was precluded by the small size of our study.

Improvements were seen within both the yoga and strengthening groups from baseline to post-intervention in multiple dimensions of the CRF (general fatigue, mental fatigue, vigor, and total score) but not in the emotional and physical CRF subscales. All of the CRF sub-scores improved from baseline to 3 months post-intervention within the yoga group, whereas in the strengthening group, only the vigor sub-score maintained its significant improvement at 3 months post-intervention (Table 5). However, there was no difference between groups in any of the CRF sub-scores at baseline, and no significant differences were seen between the groups with respect to change in scores at post-intervention and at 3 months post-intervention. Figure 2a, b depicts the changes in the total CRF and total QOL scores from baseline to 3 months post-intervention.

The QOL scores followed a similar pattern, with the physical and functional well-being, as well as the FACT-G, the total score, and the trial outcome index improving significantly within both groups from baseline to post-intervention. Exceptions were the Breast Cancer Subscale and the social and emotional components, which did not change. At 3 months post-intervention, the yoga group maintained all these significant improvements in QOL, whereas the strengthening group maintained the improvements only in the physical well-being, Breast Cancer Subscale, and the Trial Outcome Index (Table 5). None of the QOL subscales showed intergroup differences at baseline, post-intervention, and 3 months post-intervention.

When considering the mean difference in scores from baseline, MIDs were demonstrated in the strengthening group only for the Breast Cancer Subscale and only at post-intervention, whereas the yoga group improved on all the QOL subscales for which MIDs are available (Breast Cancer Subscale, FACT-G, Fact-B Total Score, and Trial Outcome Index; Table 5) at post-intervention, and except for the Breast Cancer Subscale, maintained all these significant gains at 3 months post-intervention.

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that among breast cancer survivors diagnosed with CRF, both a yoga intervention and a resistive strengthening exercise intervention performed within 1 year from the diagnosis were equally feasible and equally improved CRF and QOL. Significant improvements were identified within both groups when evaluating both CRF and QOL from baseline to post-intervention and from baseline to 3 months post-intervention. Clinically significant improvements in some of the QOL subscales were more common and persistent in the yoga group compared to the strengthening group. This suggests that both interventions might be valuable in the rehabilitation of cancer survivors affected by CRF. Mild side effects developed in six participants in the yoga group, such as pain in the arm, side, and legs, but this did not interfere with the study participation; in contrast, the two participants who developed side effects in the strengthening group (DeQuervain tendinitis and arm pain, respectively) opted to discontinue the study. Given the gentle nature of the yoga poses and the fact that many patients were still undergoing breast reconstruction while enrolled in this study, it is possible that most of the side effects noted within the yoga group can be attributed to recent reconstructive surgeries or medication side effects, rather than the yoga intervention. In retrospect, we feel that more instruction should have been given face-to-face especially for the strengthening bands group, where the side effects of De Quervain tenosynovitis and arm pain were likely attributable to the intervention.

The lack of a non-intervention group in our study, however, makes it difficult to attribute the benefits to the actual interventions rather than to the simple passage of time. A similar study exploring the effects of yoga in breast cancer survivors (N = 31) with persistent CRF beyond 6 months after treatment completion showed that yoga was superior to a health education intervention in improving CRF and vigor at post-intervention and at 3 months post-intervention [4]. The findings of this study, combined with the results from our study, might suggest that an active intervention, mindfulness-based or strength-based, is superior to a non-active intervention in improving CRF.

Supporting this view is a study of yoga versus stretching exercises versus wait list in 163 breast cancer survivors undergoing radiation therapy [26]. In this trial, CRF improved significantly from baseline to post-intervention within both the yoga and the stretching groups, without intergroup differences, and this improvement was significantly higher than that seen on the waitlist group. The physical component of the QOL improved significantly more in the yoga group compared to the other two groups at 1, 3, and 6 months post-radiation, but there was no difference in the mental component of QOL between the groups. In our study, the physical component of QOL improved similarly in both groups, whereas the mental component did not change.

In contrast to these findings, a multi-ethnic sample (N = 128) of breast cancer survivors receiving Iyengar yoga showed no difference in the overall QOL, CRF, and sleep when compared to a waitlist group [23]. The social well-being sub-score of the QOL was the only outcome with a significant improvement in the yoga compared to the control group, suggesting a benefit from the social interaction with other cancer survivors during the yoga classes. The home-based design of our study offered minimal social interaction during the follow-up phone calls, which might explain the lack of benefit in the social well-being domain in either group.

Also in the Moadel study [23], those with a higher adherence to the yoga intervention (>6 classes/week) had significantly lower level of CRF, distress, and better emotional well-being when compared to low- or non-adherers. Similarly, in our study, the functional domain of the QOL and the vigor domain of CRF improved more for compliant (from both groups taken together) as opposed to the non-compliant participants.

Adherence to the yoga (39 %) and the strengthening (44 %) interventions in our study was low, despite our bi-monthly telephone contact to encourage participation. Other studies of yoga in a similar breast cancer population reported adherence rates of 60–85 % [23, 26], but in these studies, the yoga intervention was instructor-based and delivered in a group setting. The participants in our study might have been less motivated to exercise given the lack of a scheduled class or the peer pressure that a group intervention provides; rather, they relied on self-discipline and the bi-weekly phone calls for motivation and encouragement.

An 8-week, home-based intervention trial in patients with metastatic colon or lung cancer, comparing a non-intervention group with a walking plus strengthening (using the same strengthening REST DVD as our study) plus bi-monthly phone calls group, showed an adherence rate of 77 % [27]. The high adherence in this study, despite selecting a sicker population affected by metastatic disease, might be explained by the appealing design that allowed for advancement of the exercise routine during the bi-monthly phone calls. By comparison, in our study, the yoga was maintained at a gentle level, although the strengthening group was instructed to advance the resistance level. Indeed, one participant in the yoga group discontinued participation due to “lack of effect of the intervention,” and others have commented that they would have liked to advance to a more challenging level of yoga. All responders to the recruitment letter in our study had a DVD in their household, suggesting that DVD interventions are feasible outside of an organized in-person class in the USA.

A recent integrative data analysis of three of the largest home-based diet and exercise interventions in cancer survivors, looking at predictors of enrollment, adherence, and completion of the study, reported a combined adherence rate of 51 %, only slightly above our study [38]. It appears that a home-based intervention solely through DVD and phone calls may not suffice to achieve adequate and sustained levels of activity in many survivors of breast cancer. Another systematic review of trials of physical activity and behavior change interventions in recent post-treatment breast cancer survivors demonstrated that the largest effect on behavior change came from more intense interventions such as in-person and frequent interactions, although significant improvements were also noted from the home-based, telephone, or email-based interventions [39].

These studies suggest that a combination of a class/group exercise with home-based interventions might provide the flexibility and motivation for a better adherence to exercise interventions. A more intense and frequent, possibly weekly, phone interaction might provide additional motivation to enhance adherence.

Our study was limited by the small size and might not be generalizable to a larger population. As such, a larger clinical trial utilizing sham treatments and a longer follow-up period is needed to conclusively compare the two treatments. Such study may not be feasible though, given the similarities between the groups regarding the fatigue score changes: for example, considering the MFSI general outcome, the average difference from baseline to post-intervention was −2.8 (SD 4.5) in the strengthening group and −3.2 (SD 4.2) in the yoga group. These groups are truly quite similar with this difference of only 0.4. Under the same conditions in a new study, with the same standard deviations, we would need 1861 women per group in order to find a difference this small as statistically significant with 80 % power, 5 % type I error rate.

Another limitation was the lack of in-person contact with an instructor before and during the intervention, to prevent inaccurate postures or movements, which might have led to some of the side effects noted in both groups. Whereas a face-to-face visit with an instructor at the baseline visit might be warranted, such in-person visits during the intervention would decrease the convenience that this home-based program provided, especially for participants from remote areas.

The two interventions were considerably different in duration (yoga—90 min, strengthening bands—20 min). This might have impacted the results toward the yoga group receiving more benefit from the intervention relative to the strengthening group. Future studies should adopt interventions that are similar in length.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated a positive effect of both yoga and strengthening exercises toward improving CRF and QOL among breast cancer survivors when performed within 12 months from the breast cancer diagnosis despite a limited adherence to these interventions, suggesting that both mindfulness-based and more traditional physical exercises might be equally beneficial for this population. Larger studies are needed to more accurately assess the impact of these interventions on CRF and QOL in breast cancer survivors.

References

American Cancer Society. Cancer treatment & survivorship facts & figures 2014–2015. 2014 [cited 2015 October 28]; Available from: http://www.cancer.org/research/cancerfactsstatistics/survivor-facts-figures.

Potash J, Anderson KC (2014) AACR cancer progress report 2014: transforming lives through research. Clin Cancer Res 20(19):4977

Hofman M et al (2007) Cancer-related fatigue: the scale of the problem. Oncologist 12(Suppl 1):4–10

Bower JE, Garet D, Sternlieb B, Ganz PA, Irwin MR, Olmstead R, Greendale G (2012) Yoga for persistent fatigue in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer 118(15):3766–3775. doi:10.1002/cncr.26702

Bower JE et al (2006) Fatigue in long-term breast carcinoma survivors: a longitudinal investigation. Cancer 106(4):751–8

NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. NCCN Guidelines for Supportive Care: Cancer-related Fatigue. [Guidelines] 2014 11/21/2012 [cited 2015 October 28]; Available from: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp.

Schmidt, M.E. et al., Effects of resistance exercise on fatigue and quality of life in breast cancer patients undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy: a randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Cancer. Journal international du cancer, 2014

Steindorf K et al (2014) Randomized, controlled trial of resistance training in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant radiotherapy: results on cancer-related fatigue and quality of life. Ann Oncol 25(11):2237–43

Rogers LQ et al (2015) Effects of the BEAT Cancer physical activity behavior change intervention on physical activity, aerobic fitness, and quality of life in breast cancer survivors: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat 149(1):109–19

Murtezani A et al (2014) The effect of aerobic exercise on quality of life among breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. J Cancer Res Ther 10(3):658–664

Milne HM et al (2008) Effects of a combined aerobic and resistance exercise program in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat 108(2):279–288

Schmitz KH et al (2009) Weight lifting in women with breast-cancer-related lymphedema. N Engl J Med 361(7):664–73

Sagen A, Karesen R, Risberg MA (2009) Physical activity for the affected limb and arm lymphedema after breast cancer surgery. A prospective, randomized controlled trial with two years follow-up. Acta Oncol 48(8):1102–10

Holmes MD et al (2005) Physical activity and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. JAMA 293(20):2479–86

de Glas NA et al (2014) Physical activity and survival of postmenopausal, hormone receptor-positive breast cancer patients results of the Tamoxifen Exemestane Adjuvant Multicenter Lifestyle study. Cancer 120(18):2847–2854

Wanchai A, Armer JM, Stewart BR (2010) Complementary and alternative medicine use among women with breast cancer: a systematic review. Clin J Oncol Nurs 14(4):E45–55

Stan DL et al (2012) The evolution of mindfulness-based physical interventions in breast cancer survivors. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2012:758641

Greenlee H et al (2014) Clinical practice guidelines on the use of integrative therapies as supportive care in patients treated for breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2014(50):346–58

Bower JE et al (2005) Yoga for cancer patients and survivors. Cancer Control 12(3):165–71

Vadiraja HS et al (2009) Effects of yoga program on quality of life and affect in early breast cancer patients undergoing adjuvant radiotherapy: a randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Med 17(5-6):274–80

Chandwani KD et al (2010) Yoga improves quality of life and benefit finding in women undergoing radiotherapy for breast cancer. J Soc Integr Oncol 8(2):43–55

Banasik J et al (2011) Effect of Iyengar yoga practice on fatigue and diurnal salivary cortisol concentration in breast cancer survivors. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 23(3):135–42

Moadel AB et al (2007) Randomized controlled trial of yoga among a multiethnic sample of breast cancer patients: effects on quality of life. J Clin Oncol 25(28):4387–95

Littman AJ et al (2012) Randomized controlled pilot trial of yoga in overweight and obese breast cancer survivors: effects on quality of life and anthropometric measures. Support Care Cancer 20(2):267–77

Kiecolt-Glaser JK et al (2014) Yoga’s impact on inflammation, mood, and fatigue in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 32(10):1040–9

Chandwani KD et al (2014) Randomized, controlled trial of yoga in women with breast cancer undergoing radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol 32(10):1058–65

Cheville AL et al (2013) A home-based exercise program to improve function, fatigue, and sleep quality in patients with stage IV lung and colorectal cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manag 45(5):811–21

Berger AM et al (2010) Cancer-related fatigue. JNCCN 8(8):904–31

Donovan KA, Jacobsen PB (2010) The Fatigue Symptom Inventory: a systematic review of its psychometric properties. Support Care Cancer 19(2):169–85

Hann DM et al (1998) Measurement of fatigue in cancer patients: development and validation of the Fatigue Symptom Inventory. Qual Life Res 7(4):301–10

Stein KD et al (2004) Further validation of the multidimensional fatigue symptom inventory-short form. J Pain Symptom Manag 27(1):14–23

Stein KD et al (1998) A multidimensional measure of fatigue for use with cancer patients. Cancer Pract 6(3):143–52

Cella DF et al (1993) The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol 11(3):570–9

Coster S, Poole K, Fallowfield LJ (2001) The validation of a quality of life scale to assess the impact of arm morbidity in breast cancer patients post-operatively. Breast Cancer Res Treat 68(3):273–82

Beaulac SM et al (2002) Lymphedema and quality of life in survivors of early-stage breast cancer. Arch Surg 137(11):1253–7

Eton DT et al (2004) A combination of distribution- and anchor-based approaches determined minimally important differences (MIDs) for four endpoints in a breast cancer scale. J Clin Epidemiol 57(9):898–910

Clark MM et al (2013) Randomized controlled trial of maintaining quality of life during radiotherapy for advanced cancer. Cancer 119(4):880–7

Adams R et al (2015) Cancer survivors’ uptake and adherence in diet and exercise intervention trials: an integrative data analysis. Cancer 121(1):77–83

Bluethmann SM et al (2015) Taking the next step: a systematic review and meta-analysis of physical activity and behavior change interventions in recent post-treatment breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat 149(2):331–42

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge our valuable participants, and we thank Lace Up Against Breast Cancer (LAUBC) for funding this study. Special thanks go to Mrs. Kristi Simmons and Mrs. Linda C. Allen for help with editing the manuscript. We are indebted to Camille Kittrell, M.S., producer of the Exclusive Yoga DVD, for allowing us to use this program in our study. This paper was presented as an oral presentation at the Supportive Care in Cancer MASCC/ISOO 2015 International Symposium in Copenhagen on June 25–27, 2015.

Authors’ contributions

All the authors were involved with development of the study concept, design, data analysis, and manuscript writing and editing. Dr. Stan, Dr. Ivana Croghan, and Dr. Pruthi were involved with study oversight. Katrina Croghan participated in patient recruitment, data collection, and development of study materials. Sarah Jenkins provided statistical support. Dr. Cheville was part of the team that developed the REST strengthening exercise DVD used in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stan, D.L., Croghan, K.A., Croghan, I.T. et al. Randomized pilot trial of yoga versus strengthening exercises in breast cancer survivors with cancer-related fatigue. Support Care Cancer 24, 4005–4015 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3233-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3233-z