Abstract

Many authors showed that aquatic physiotherapy could improve quality of life and reduce postural instability and risk of falling in elderly subjects. The aim of this research was to explore if the thermal aquatic environment is a suitable place for rehabilitative training in person with Parkinson disease (PwP) with results comparable to the standard physiotherapy. A retrospective study was conducted on a database of 14 persons with Parkinson who were admitted to a thermal aquatic rehabilitation to undergo treatments made to improve gait and balance impairments. The rehabilitation training consisted of 45-min sessions conducted twice a week, on non-consecutive days, over 4 weeks of functional re-education and kinesitherapy in the thermal pool. Educational and prevention instructions were also given to the patients during each session. Additionally, nutrition (diet), health education, and cognitive behavioral advice were given to our patients by therapists. The clinical characteristics of the sample were age 66 ± 9, disease duration 7 ± 5, and Hoehn and Yahr 1.5 ± 0.5. The statistical analysis showed a statistically significant improvement for the UPDRS p = 0.0005, for The Berg Balance Scale p = 0.0078, for the PDQ8 p = 0.0039, Tinetti p = 0.0068, and for Mini BESTest p = 0.0002. Our data suggest that this intervention could become a useful strategy in the rehabilitation program of PwP. The simplicity of treatment and the lack of side effects endorse the use of thermal aquatic environment for the gait and balance recovery in PwP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Health and demographic trends are changing in the last decade; in particular, the number of people living with chronic and/or degenerative diseases reached 2 billion (Stewart Williams et al. 2015). The rehabilitative treatment aims people with Parkinson disease (PwP) to maintain their higher level of mobility, activity, and independence. Pellecchia et al. demonstrated that a long-term rehabilitation program could be achieved through a sustained improvement of motor skills (Pellecchia et al. 2004). Various land-based physiotherapy protocols have been developed, validated, and used to improve gait spatiotemporal parameters, such as velocity and step amplitude (Vivas et al. 2011), but it is also still difficult to define guidelines for the right procedures. Aquatic physiotherapy can be used with higher therapeutic efficacy for a great variety of impairments and has been demonstrated to be also a valid alternative to land-based protocols (Zotz et al. 2013). Various authors suggested that aquatic physiotherapy could improve quality of life and reduce postural instability and risk of falling in elderly (Vivas et al. 2011). The same results could be reached also for musculoskeletal disorders (Suomi and Koceja 2000; Devereux et al. 2005; Masiero 2008; Arnold et al. 2008; Paoloni et al. 2017; Mazzoli et al. 2017; Masiero et al. 2018). Recently, Li and colleagues have highlighted that aquatic therapy was also indicated for neurological impairments (Li et al. 2017), for example, for balance and gait disorder in individuals with stroke (Montagna et al. 2014; Tripp and Krakow 2014; Furnari et al. 2014; Park et al. 2015, 2016; Zhu et al. 2016; Zhang et al. 2016; Morer et al. 2017). In these subjects, the main effects could be achieved on postural balance and knee flexor strength (Dong Koog Noh et al. 2008; Park et al. 2015, 2016). Volpe and colleagues have postulated that the water environment on subject with PwP, because of its microgravity-like properties, could provide therapeutic changes on postural deformities (Volpe et al. 2014, 2017). In a recent paper, Zhu and colleagues showed the results of a new rehabilitative protocol based on the effect of aquatic obstacle training on balance in comparison with a traditional aquatic therapy in PwP (Zhu et al. 2018). The aim of this research was to explore if the aquatic thermal environment is a suitable place for providing rehabilitative treatment in PwP, with results comparable to the conventional physiotherapy and with an impact on quality of life.

Materials and methods

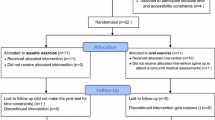

A retrospective study was conducted on a database of PwP who were admitted to a thermal rehabilitation center in Abano Terme (Italy) to improve gait and balance impairments. The patients’ data had been extracted from the health care institute’s database. The inclusion criteria were as follows: diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease stages 1, 2, or 3 according to the Hoehn and Yahr Scale in the OFF-medication phase (in absence of the effect of medication); age comprised between 45 to 95 years, gait and/or balance impairment; lack of dementia (Mini Mental State Examination score > 24).

The exclusion criteria were inability to walk independently, fixed postural deformities, major depression (DSMIV Criteria), implant for deep brain stimulation, severe cardiac, pulmonary, or orthopedic diseases co-morbidities or urinary incontinence, presence of cardiovascular disease including phlebitis or deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary, cutaneous, neoplastic, and mental diseases.

Rehabilitation intervention and educational program

The evaluation protocols were assessed the day of admission (T0) and at the end of the rehabilitative training (T1) in OFF state, by a trained MD not included into this study. A single physiotherapist performed the aquatic thermal training in a small group of 3 to 5 participants. All 45-min sessions were conducted twice a week, on non-consecutive days, over 4 weeks. During the training, the participants were allowed to continue their usual motor activities, without practice on any specific physiotherapy and with no change in medication. According to Musumeci and colleagues, the rehabilitation training consisted of functional re-education, kinesitherapy in the thermal pool with salso-bromo-iodic water, nutrition (diet), health education, and cognitive behavioral advice (Musumeci et al. 2018).

Clinical examination

The demographic (age and sex) and the following clinical records were exported from the database:

-

1.

Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS): the unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale (UPDRS) is used to follow the longitudinal course of Parkinson’s disease (Stocchi et al. 2015).

-

2.

Hoehn and Yahr Scale: it is a commonly used system for describing how the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease progress (Sale et al. 2013).

-

3.

Berg Balance Scale (BBS): a 14-item scale for assessing balance; the items are scored from 0 (unable to execute the task) to 4 (independent) with the higher score indicating the degree of independence displayed while performing different tasks (Geroin et al. 2013).

-

4.

Mini BESTest: this clinical balance assessment tool is a shortened version of the Balance Evaluation Systems Test (BESTest). It aims to target and identify six different balance control systems so that specific rehabilitation approaches can be designed for different balance deficits (Ferrazzoli et al. 2016)

-

5.

Timed Up and Go (TUG): subjects were seated on a chair, and once commanded, they stand up, walk for 3 m, turn, come back, and sit down on the chair again. The time was recorded with a stopwatch three times (Bovolenta et al. 2011).

-

6.

Tinetti balance assessment tool (Tinetti) Scale: it assesses perception of balance and stability during activities of daily living and fear of falling in the elderly population (Franceschini et al. 2015).

-

7.

The Parkinson’s Disease Questionaire-8 (PDQ8): a self-administered questionnaire, used to measure quality of life in persons with Parkinson’s disease (Huang et al. 2011).

-

8.

Falls Efficacy Scale (FES): a 16-item self-administered questionnaire designed to assess fear of falling in mainly community-dwelling older population (Dewan and MacDermid 2014) .

-

9.

FOG Scale: The FOGQ assesses freezing of gait (FOG) severity unrelated to falls in patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD), FOG frequency, disturbances in gait, and relationship to clinical features conceptually associated with gait and motor aspects (e.g., turning) (Tan et al. 2011).

Patients’ anonymity was preserved. The Berg Balance Scale and Tinetti were defined as the primary outcome.

Ethical issue

The Italian Data Protection Authority (Garante per la protezione dei dati personali) declared that the Italian University can perform retrospectives studies without the approval of the local Ethical Committee (Stewart Williams et al. 2015).

Statistical methods

A preliminary descriptive analysis was performed to check the normal distribution of patients’ clinical and instrumental data using Shapiro-Wilk test. If the variables collected present a normal distribution, parametric statistic tests were used; if not, non-parametric tests were used. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to determine the location of any significant differences between time points. The alpha level for significance were set at p < 0.05 for first level of analysis.

Results

We analyzed 14 subjects that met the inclusion criteria. Aquatic thermal physiotherapy was found to be safe, with no adverse events, extreme fatigue, or exacerbation of PD symptoms, and the training program was very enjoyable for all the participants. No dropouts were recorded during the treatment and all subjects fulfilled the protocol (compliant subjects: N = 14). Table 1 summarizes the observed mean and standard deviation, the change between T0 and T1 in terms of percentage, and p values for all tests (Table 1). Clinical improvements were found in all patients that fulfilled the protocol. The statistical analysis of all subjects showed a significant improvement for the UPDRS p = 0.0005 with an improvement of − 32%: (UPDRS part 1 (p = 0.0035) with an improvement of − 15%; for the UPDRS part 2 p = 0.0012 with an improvement of − 39%, UPDRS part 3 p = 0.0005 with an improvement of − 24%, UPDRS part 4 p = 0.0078 with an improvement of − 36%). The Berg Balance Scale showed an improvement of 9% with p values of p = 0.0078; the FOG Scale a p value of p = 0.0156 and an improvement of 18%; the PDQ8 p values of p = 0.0039 with an improvement of − 23%; the Tinetti p = 0.0068 with an improvement of 8%, and the Mini BESTest a p value of p = 0.0002 with an improvement of 18% (Fig. 1).

Discussion

This research highlights that the aquatic thermal environment could be a suitable place for providing a suitable rehabilitative treatment for PwP. The management of PwP traditionally has been centered, until now, on drug therapy (Abbruzzese et al. 2016) but recently, the rehabilitation therapies has been highlighted as an adjuvant to pharmacological and neurosurgical treatment in PwP (Sale et al. 2013). Starting from our clinical experiences, the statistical analyses demonstrated and confirmed a hopeful improvement in all clinical scales analyzed in our subject after aquatic thermal physiotherapy. In particular, the improvement on Berg Balance Scale, Tinetti, and Mini BESTest are in accordance with the recent papers published by Volpe and by Vivas (Vivas et al. 2011; Volpe et al. 2014, 2017). Our data confirmed the improvement in postural stability in PwP after aquatic therapy (Vivas et al. 2011; Volpe et al. 2014, 2017) and are also in accordance with Devereux and colleagues about the role of rehabilitative approach based on aquatic physiotherapy on improvement on quality of life and on reduction of postural instability and risk of falling in elderly (Devereux et al. 2005). The statistical improvement in our scores of PDQ8 and UPDRS confirmed these suggestions. The results about the improvement on motor function assessed by UPDRS part III following the aquatic thermal therapy are also in agreement with Vivas and Cancela (Vivas et al. 2011; Ayán and Cancela 2012).

Until now, more papers highlighted that physiotherapy improves in PwP the UPDRS but evidences using exclusively water-based therapy for people with PD are scarce (Magrinelli et al. 2016; Abbruzzese et al. 2016; Mak et al. 2017). The physio-pathological basis of these results could be more and various. Thermal aquatic therapy was also used for its anti-edemigenous and anti-inflammatory, muscle relaxant, muscle trophic, and antalgic physical properties, and have been demonstrated to be both enjoyable and to produce neuroprotective effect (Carroll et al. 2017). Moreover, we confirmed also the Musumeci results about the benefits of water immersion exercise combining with the chemical and physical effects of thermal water itself (Musumeci et al. 2018). The reduction fear of falling in water is another important finding of our results that are in accordance with Vivas and colleagues that demonstrated the role of the buoyancy and the hydrostatic pressure offered by water about to promote body support and to reduce the velocity of falls (Vivas et al. 2011). Fiorvanti and colleagues demonstrated that aquatic exercises may help in fostering more extensive movements with less muscular effort, reduce joint compression and weight load, and facilitate the patient in regaining his lower limb strength and movement (Fioravanti et al. 2011). As reported by Abruzzese and Vivad, we can confirm that the “warm water” could have a strength therapeutic effect on body and muscle rigidity (Vivas et al. 2011; Abbruzzese et al. 2016). Our experiences suggest also that the placebo effect of hot water could also be the reason why a more innovative approach (water-based) has a better effect. Kauffman and colleagues suggest that maintaining of a good water environment in term of temperatures, where the body neither gains nor loses temperature while in the water (33.5–34.5 °C), is important to allow a good therapeutic exercise environment to facilitate therapeutic benefits (Kauffman and Kauffman 2014; Kauffman et al. 2014).

Study limitations

This retrospective study is based on a small study sample at one study site and used no blinding nor control group. The study included a selected subgroup of patients, who are not representative for the whole PwP with regard to age, gender, or H&Y impairments. Thus, the findings are only relevant for the subgroup at study and cannot be generalized to the whole Parkinson population.

Conclusion

The statistical improvement in a low number of people analyzed was also very interesting. We demonstrated that thermal aquatic rehabilitation might become a useful strategy in the rehabilitation program of PwP. The simplicity of treatment and the lack of side effects in this research endorse the development of new large randomized clinical trial. In order to better investigate our results, future study should include a larger number of subjects with a long-term follow-up.

References

Abbruzzese G, Marchese R, Avanzino L, Pelosin E (2016) Rehabilitation for Parkinson’s disease: current outlook and future challenges. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 22:S60–S64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.09.005

Arnold CM, Busch AJ, Schachter CL, Harrison EL, Olszynski WP (2008) A randomized clinical trial of aquatic versus land exercise to improve balance, function, and quality of life in older women with osteoporosis. Physiother Can 60:296–306. https://doi.org/10.3138/physio.60.4.296

Ayán C, Cancela J (2012) Feasibility of 2 different water-based exercise training programs in patients with Parkinson’s disease: a pilot study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 93:1709–1714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2012.03.029

Bovolenta F, Sale P, Dall’Armi V et al (2011) Robot-aided therapy for upper limbs in patients with stroke-related lesions. Brief report of a clinical experience. J Neuroeng Rehabil 8:18. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-0003-8-18

Carroll LM, Volpe D, Morris ME, Saunders J, Clifford AM (2017) Aquatic exercise therapy for people with Parkinson disease: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 98:631–638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2016.12.006

Devereux K, Robertson D, Briffa NK (2005) Effects of a water-based program on women 65 years and over: a randomised controlled trial. Aust J Physiother 51:102–108

Dewan N, MacDermid JC (2014) Fall efficacy scale - international (FES-I). J Physiother 60:60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphys.2013.12.014

Dong Koog Noh DK, Lim J-Y, Shin H-I, Paik N-J (2008) The effect of aquatic therapy on postural balance and muscle strength in stroke survivors — a randomized controlled pilot trial. Clin Rehabil 22:966–976. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215508091434

Ferrazzoli D, Ortelli P, Maestri R, Bera R, Giladi N, Ghilardi MF, Pezzoli G, Frazzitta G (2016) Does cognitive impairment affect rehabilitation outcome in Parkinson’s disease? Front Aging Neurosci 8:192. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2016.00192

Fioravanti A, Cantarini L, Guidelli GM, Galeazzi M (2011) Mechanisms of action of spa therapies in rheumatic diseases: what scientific evidence is there? Rheumatol Int 31:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-010-1628-6

Franceschini M, Colombo R, Posteraro F, Sale P (2015) A proposal for an Italian minimum data set assessment protocol for robot-assisted rehabilitation: a Delphi study. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 51:745–753

Furnari A, Calabrò RS, Gervasi G, la Fauci-Belponer F, Marzo A, Berbiglia F, Paladina G, de Cola MC, Bramanti P (2014) Is hydrokinesitherapy effective on gait and balance in patients with stroke? A clinical and baropodometric investigation. Brain Inj 28:1109–1114. https://doi.org/10.3109/02699052.2014.910700

Geroin C, Mazzoleni S, Smania N, Gandolfi M, Bonaiuti D, Gasperini G, Sale P, Munari D, Waldner A, Spidalieri R, Bovolenta F, Picelli A, Posteraro F, Molteni F, Franceschini M, Italian Robotic Neurorehabilitation Research Group (2013) Systematic review of outcome measures of walking training using electromechanical and robotic devices in patients with stroke. J Rehabil Med 45:987–996. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-1234

Huang T-T, Hsu H-Y, Wang B-H, Chen K-H (2011) Quality of life in Parkinson’s disease patients: validation of the short-form eight-item Parkinson’s disease questionnaire (PDQ-8) in Taiwan. Qual Life Res 20:499–505. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-010-9777-3

Kauffman BE, Kauffman BW (2014) Aquatic therapy. In: A Comprehensive Guide to Geriatric Rehabilitation. Elsevier, pp 517–519

Kauffman TL, Scott RW, Barr JO, Moran ML (2014) A comprehensive guide to geriatric rehabilitation, 3rd edn. Churchill Livingstone (Elsevier), London, p 624

Li C, Khoo S, Adnan A (2017) Effects of aquatic exercise on physical function and fitness among people with spinal cord injury: a systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore) 96:e6328. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000006328

Magrinelli F, Picelli A, Tocco P, Federico A, Roncari L, Smania N, Zanette G, Tamburin S (2016) Pathophysiology of motor dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease as the rationale for drug treatment and rehabilitation. Parkinsons Dis 2016:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/9832839

Mak MK, Wong-Yu IS, Shen X, Chung CL (2017) Long-term effects of exercise and physical therapy in people with Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Neurol 13:689–703. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2017.128

Masiero S (2008) Thermal rehabilitation and osteoarticular diseases of the elderly. Aging Clin Exp Res 20:189–194. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03324772

Masiero S, Vittadini F, Ferroni C, Bosco A, Serra R, Frigo AC, Frizziero A (2018) The role of thermal balneotherapy in the treatment of obese patient with knee osteoarthritis. Int J Biometeorol 62:243–252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-017-1445-7

Mazzoli D, Giannotti E, Longhi M, Prati P, Masiero S, Merlo A (2017) Age explains limited hip extension recovery at one year from total hip arthroplasty. Clin Biomech 48:35–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2017.07.003

Montagna JC, Santos BC, Battistuzzo CR, Loureiro APC (2014) Effects of aquatic physiotherapy on the improvement of balance and corporal symmetry in stroke survivors. Int J Clin Exp Med 7:1182–1187

Morer C, Boestad C, Zuluaga P, Alvarez-Badillo A, Maraver F (2017) Effects of an intensive thalassotherapy and aquatic therapy program in stroke patients. A pilot study. Rev Neurol 65:249–256

Musumeci A, Pranovi G, Masiero S (2018) Patient education and rehabilitation after hip arthroplasty in an Italian spa center: a pilot study on its feasibility. Int J Biometeorol 62:1489–1496. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-018-1548-9

Paoloni M, Bernetti A, Brignoli O et al (2017) Appropriateness and efficacy of Spa therapy for musculoskeletal disorders. A Delphi method consensus initiative among experts in Italy. Ann Ist Super Sanita 53:70–76 http://old.iss.it/binary/publ/cont/ANN_17_01_13.pdf

Park B-S, Noh J-W, Kim M-Y, Lee LK, Yang SM, Lee WD, Shin YS, Kim JH, Lee JU, Kwak TY, Lee TH, Kim JY, Park J, Kim J (2015) The effects of aquatic trunk exercise on gait and muscle activity in stroke patients: a randomized controlled pilot study. J Phys Ther Sci 27:3549–3553. https://doi.org/10.1589/jpts.27.3549

Park B-S, Noh J-W, Kim M-Y, Lee LK, Yang SM, Lee WD, Shin YS, Kim JH, Lee JU, Kwak TY, Lee TH, Park J, Kim J (2016) A comparative study of the effects of trunk exercise program in aquatic and land-based therapy on gait in hemiplegic stroke patients. J Phys Ther Sci 28:1904–1908. https://doi.org/10.1589/jpts.28.1904

Pellecchia MT, Grasso A, Biancardi LG, Squillante M, Bonavita V, Barone P (2004) Physical therapy in Parkinson’s disease: an open long-term rehabilitation trial. J Neurol 251:595–598. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-004-0379-2

Sale P, De Pandis MF, Domenica LP et al (2013) Robot-assisted walking training for individuals with Parkinson’s disease: a pilot randomized controlled trial. BMC Neurol 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-13-50

Stewart Williams J, Kowal P, Hestekin H et al (2015) Prevalence, risk factors and disability associated with fall-related injury in older adults in low- and middle-income countries: results from the WHO study on global AGEing and adult health (SAGE). BMC Med 13:147. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-015-0390-8

Stocchi F, Sale P, Kleiner AFR, Casali M, Cimolin V, de Pandis F, Albertini G, Galli M (2015) Long-term effects of automated mechanical peripheral stimulation on gait patterns of patients with Parkinson’s disease. Int J Rehabil Res 38:238–245. https://doi.org/10.1097/MRR.0000000000000120

Suomi R, Koceja DM (2000) Postural sway characteristics in women with lower extremity arthritis before and after an aquatic exercise intervention. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 81:780–785

Tan DM, McGinley JL, Danoudis ME et al (2011) Freezing of gait and activity limitations in people with Parkinson’s disease. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 92:1159–1165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2011.02.003

Tripp F, Krakow K (2014) Effects of an aquatic therapy approach (Halliwick-therapy) on functional mobility in subacute stroke patients: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil 28:432–439. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215513504942

Vivas J, Arias P, Cudeiro J (2011) Aquatic therapy versus conventional land-based therapy for Parkinson’s disease: an open-label pilot study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 92:1202–1210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2011.03.017

Volpe D, Giantin MG, Maestri R, Frazzitta G (2014) Comparing the effects of hydrotherapy and land-based therapy on balance in patients with Parkinson’s disease: a randomized controlled pilot study. Clin Rehabil 28:1210–1217. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215514536060

Volpe D, Giantin MG, Manuela P, Filippetto C, Pelosin E, Abbruzzese G, Antonini A (2017) Water-based vs. non-water-based physiotherapy for rehabilitation of postural deformities in Parkinson’s disease: a randomized controlled pilot study. Clin Rehabil 31:1107–1115. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215516664122

Zhang Y, Wang Y-Z, Huang L-P, Bai B, Zhou S, Yin MM, Zhao H, Zhou XN, Wang HT (2016) Aquatic therapy improves outcomes for subacute stroke patients by enhancing muscular strength of paretic lower limbs without increasing spasticity. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 95:840–849. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHM.0000000000000512

Zhu Z, Cui L, Yin M, Yu Y, Zhou X, Wang H, Yan H (2016) Hydrotherapy vs. conventional land-based exercise for improving walking and balance after stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil 30:587–593. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215515593392

Zhu Z, Yin M, Cui L, Zhang Y, Hou W, Li Y, Zhao H (2018) Aquatic obstacle training improves freezing of gait in Parkinson’s disease patients: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil 32:29–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215517715763

Zotz TGG, Souza EA, Israel VL, Loureiro APC (2013) Aquatic physical therapy for Parkinson’s disease. Adv Park Dis 02:102–107. https://doi.org/10.4236/apd.2013.24019

Acknowledgements

We thank the Medical Hotel Hermitage Bel Air for making the thermal setting available to our patients.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. All authors attest and affirm that the material within has not been and will not be submitted for publication elsewhere.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Masiero, S., Maghini, I., Mantovani, M.E. et al. Is the aquatic thermal environment a suitable place for providing rehabilitative treatment for person with Parkinson’s disease? A retrospective study. Int J Biometeorol 63, 13–18 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-018-1632-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-018-1632-1