Abstract

Objective

This prospective randomized trial compared the invasiveness of laparoscopic gastrectomy using a single-port approach with that of a conventional multi-port approach in the treatment of gastric cancer.

Summary Background Data

The benefit of single-port laparoscopic gastrectomy (SLG) over multi-port laparoscopic gastrectomy (MLG) has yet to be confirmed in a well-designed study.

Methods

One hundred and one patients who were scheduled to undergo laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for histologically confirmed clinical stage I gastric cancer between April 2016 and September 2018 were randomly allocated to SLG (n = 50) or MLG (n = 51). The primary endpoints were the postoperative visual analog scale pain scores. Secondary endpoints were frequency of use of analgesia, short-term outcomes, such as operating time, intraoperative blood loss, inflammatory reactions, postoperative morbidity, and 90-day mortality.

Results

The postoperative pain score was significantly lower in the SLG group than in the MLG group (p < 0.001) on the operative day and the postoperative day 1–7. Analgesics were administered significantly less often in the SLG group than in the MLG group (1 vs. 3 days, p = 0.0078) and the duration of use of analgesics was significantly shorter in the SLG group (2 vs. 3 days, p = 0.0171). The operating time was significantly shorter in the SLG group than in the MLG group (169 vs. 182 min, p = 0.0399). Other surgical outcomes were comparable between the study groups.

Conclusions

SLG was shown to be safe and feasible in the treatment of gastric cancer with better short-term results in terms of less severe pain and may be suitable for treatment of cStage I gastric cancer.

Clinical trial registration:

UMIN000022218

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The introduction of laparoscopic surgery has significantly improved the outcome after gastrectomy for gastric cancer because it is associated with less blood loss, more rapid recovery, less pain, and a shorter postoperative hospital stay [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8] with more acceptable oncologic outcomes than the open approach [9, 10]. This demonstration of superiority has allowed development of less invasive procedures. Single-port surgery, which is performed via one port in the umbilicus, is the goal of minimally invasive surgery in the clinical setting.

Since the first report of single-incision trans-umbilical laparoscopic distal gastrectomy (SLG) for gastric cancer by Omori et al. [11], this surgical strategy has been introduced in several institutions, mainly in East Asian countries such as Japan and Korea [11,12,13,14,15]. Although SLG is reportedly difficult because of the propensity for instrument collisions, lack of triangulation, and the limited number of available ports [11, 12, 14], standardization of this procedure could result in a relatively simple operation [16]. Nevertheless, this surgical approach is not common worldwide because of lack of data on the effectiveness of SLG and the difficulty of the procedure.

In a case-matched comparative study, SLG with D1 + lymphadenectomy was associated with a similar operating time but less blood loss, and less pain than MLG [14]. In a previous propensity score-matched comparative study, we showed that SLG with D2 lymphadenectomy for clinical stage I–III gastric cancer was less invasive in terms of less blood loss, less postoperative pain, more rapid bowel recovery, a shorter postoperative hospital stay, a less severe inflammatory reaction, and more acceptable oncologic outcomes than MLG [15]. The 5-year overall survival rate in patients with advanced (stage II–IV) gastric cancer was comparable between SLG and MLG [17]. However, a retrospective study reported by Kim et al. showed that postoperative pain was similar between an SLG group and an MLG group [18].

Although single-port gastrectomy for gastric cancer has been reported to be safe and feasible in non-randomized retrospective studies, the efficacy of this surgery remains controversial, with no confirmatory data from a randomized controlled trial published thus far. Therefore, the aim of this randomized controlled study was to compare postoperative pain, surgical outcomes, and the postoperative course in patients undergoing SLG or MLG for gastric cancer.

Methods

Trial design

This single-center, open-label, prospective randomized controlled trial was conducted to evaluate MLG versus SLG in patient with clinical stage I gastric cancer, operated between April 2016 and September 2018. Superiority of SLG to MLG with regards to reduced postoperative pain was hypothesized. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Osaka International Cancer Institute (No. 1512046225). All patients provided written informed consent. The data were collected and analyzed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1975). Patients were withdrawn from the study if they withdrew consent or experiences a serious adverse event. The study is registered in the University Hospital Medical Information Network—Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN000022218).

Sample size calculation

According to a previously published report, postoperative pain score using the VAS (Visual analog scale) score on POD 1 was 4.5 in an SLG group and 5.5 in an MLG group [14]. The sample size was calculated based on a statistical power of 80% to detect an absolute difference in scores for each category, assuming a 20% reduction in the SLG group compared with the MLG group at an alpha of 0.05 and allowing for a dropout rate of 20%. It was found that 100 patients would need to be enrolled in the study.

Participants

This single-center prospective randomized Phase II study included patients who underwent distal gastrectomy with D1 + or D2 lymphadenectomy in our institute. Eligible participants were histologically proven gastric cancer (clinical stage I) and were aged 20–80 years. The following exclusion criteria were applied: history of laparotomy, body mass index > 30; previous or other concomitant cancer; a renal, hepatic, or metabolic disorder (e.g., severe diabetes); cardiac disease; and a history of gastrectomy.

Study endpoints

The primary study endpoint was the visual analog scale (VAS) pain score at rest on postoperative days (PODs) 1. The secondary endpoints were VAS pain score 6 h after the operation and on postoperative days (PODs) 2–7, frequency of administration of additional analgesics, and duration of use of analgesia, the perioperative outcomes, including operating time, estimated blood loss, postoperative mortality and morbidity, postoperative inflammatory reaction, postoperative time to flatus, postoperative time to resuming oral intake, and postoperative hospital stay.

Randomization

Using an internet randomization module, the subjects were randomly allocated to an SLG group or an MLG group in a 1:1 ratio using a minimization method with a random component to balance the arms based on sex, age, and body mass index. The patients were enrolled to the study by the responsible surgeon before surgery. Patients and all investigators were unmasked to treatment assignment. Laparoscopic distal gastrectomy was performed using a single-port or multi-port approach by the same team of surgeons (TO, KY, YY).

Data collection

The data were collected prospectively and recorded in a computer database at our hospital. In the SLG group, conversion to MLG was defined as addition of any port to the abdominal wall to complete the procedure. An open conversion was defined as any extension of the primary incision for reasons other than specimen extraction or the reconstruction procedure. The indications for conversion were recorded. Morbidity was stratified as recommended by Dindo et al. [19]. The Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma, 3rd English Edition (JCGC), was used for TNM staging [20].

Pain assessment

Firstly, pain variables were evaluated using a VAS at rest and on movement (during walking) at 6 h after surgery and on PODs 1–7. Next, the abdomen was divided into four areas (umbilical, upper abdomen, right abdomen, left abdomen) and pain was evaluated for each area using a VAS.

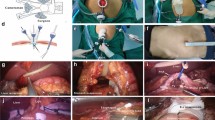

SLG procedures

We have previously reported our surgical procedure for single-port laparoscopic distal gastrectomy [13, 15, 16, 21]. Briefly, the patient is placed in the reverse Trendelenburg position with legs apart, the surgeon positioned between the patient’s legs, and an assistant on each side of the patient. A trans-umbilical laparotomy is created through a 2.5–3.0-cm vertical umbilical incision, and a wound-sealing device (Lap protector; Hakko, Nagano, Japan) is applied. Single-incision laparoscopy is then performed via a commercially available access port (EZ access; Hakko, Nagano, Japan). Pneumoperitoneum is established by insufflation of carbon dioxide at a pressure of approximately 8–12 mmHg according to the patient’s body habitus. A 10-mm high-definition flexible scope (ENDOEYE flexible HD camera system; Olympus Medical Systems Corp., Tokyo, Japan) is used to view the surgical field.

Conventional straight forceps and an ultrasonic coagulation cutting device (Harmonic ACE, Ethicon Endosurgery, Cincinnati, OH, USA) are used for gastric mobilization and lymph node dissection. For D2 lymph node dissection, we routinely check each anatomic landmark according to the JCGC criteria [15,16,17]. Distal gastrectomy is performed intracorporeally with an adequate proximal margin [22]. Finally, reconstruction is performed using the intracorporeal anastomotic technique [13, 21].

MLG procedures

We have also previously reported our surgical procedure for multi-port laparoscopic distal gastrectomy [23]. Briefly, the patient is placed on a table in the supine position with legs apart. A trans-umbilical laparotomy is created through a 2.5–3.0-cm vertical umbilical incision in the same manner as for the SLG procedure. After application of the wound-sealing device (Lap protector), the camera trocar is covered with the EZ access device. Pneumoperitoneum is then established by insufflation of carbon dioxide at a pressure of approximately 8–12 mmHg according to the patient’s body habitus Standard MLG includes five ports (one for camera port in the umbilicus, two 5-mm ports in the right abdomen, one 5-mm port in the left abdomen, and one 12-mm port in the left abdomen). The D2 lymphadenectomy procedures were performed in the same manner as that used for SLG. Reconstruction was performed using the previously reported intracorporeal anastomotic technique [13, 24,25,26].

Postoperative care

The perioperative management protocol was similar for all patients and followed our hospital’s clinical pathway. For 48 h after surgery, patients received basal analgesia by continuous intravenous infusion of fentanyl. Additional analgesia, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, was given on patient request. No patients received epidural analgesia. A soft diet was resumed after the first passage of flatus.

Statistical analysis

Patient data were analyzed on an intention-to-treat basis. All statistical calculations were performed using JMP v11.2.0 software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The demographic and clinicopathological characteristics are summarized descriptively. All quantitative values are expressed as the mean and standard deviation unless otherwise stated. Student’s t-tests or Mann–Whitney U tests and Pearson’s χ2 tests were used to compare continuous and categorical variables, respectively. All values were two-tailed, and p-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Patient flow

Between April 2016 and September 2018, 101 patients were assessed for eligibility. All patients were randomly assigned to SLG group (n = 50) or MLG group (n = 51) (Fig. 1). All patients underwent distal gastrectomy as scheduled. One patient in the MLG group underwent open conversion due to intraoperative hemorrhage and was excluded from the postoperative pain assessment.

Baseline patient characteristics

There was no statistically significant between-group difference in patient characteristics, including age, sex, body mass index, ASA physical status, type of tumor, type of reconstruction, and clinical TNM stage (Table 1). D2 lymphadenectomy tended to be more common in the SLG group than in the MLG group (76.0% vs. 58.9%), but not significantly so (p = 0.064). The distributions of pathological T stage, node status, and tumor stage according to the JCGC classification were similar [20].

Operative outcomes

Table 2 shows the perioperative results. The operating time was significantly shorter in the SLG group than in the MLG group (169 [121–275] min vs. 182 [84–345] min, p = 0.0399). Estimated blood loss was not significantly different between the two groups. One patient in the MLG group required transfusion and conversion to open surgery as a result of intraoperative hemorrhage. There were no conversions to the multi-port approach or open approach in the SLG group.

The postoperative complications are shown in Table 2. Early complications occurred in 4 patients (8%) in the SLG group and in 6 (11.8%) in the MLG group; the difference was not significant. Complications in the SLG group included wound infection and delayed gastric emptying, which were improved by conservative treatment. Complications in the MLG group included wound infection, delayed gastric emptying, and intra-abdominal fluid collection, which were improved conservatively. There were no severe complications (Clavien–Dindo grade III or higher) in either group. There was no cases of anastomotic leak, pancreatic fistula, or pneumonia in either group, or any instances of abdominal incisional hernia or anastomotic stenosis. There was no in-hospital mortality in either group.

Postoperative clinical course

Postoperative recovery was similar in the two groups. As shown in Table 3, there was no significant between-group difference in median time to first flatus or defecation. Oral intake of fluid resumed 2 days after surgery and a soft diet within 3 days; time to oral intake was equivalent between the two groups. Postoperative inflammation was also assessed. There was no significant between-group difference in the postoperative white blood cell count or serum C-reactive protein level on POD 1 and POD 3. The postoperative hospital stay was comparable between the two groups.

Postoperative pain

The postoperative VAS pain score at rest was significantly lower in the SLG group than in the MLG group 6 h after surgery (2.9 ± 0.4 vs. 6.1 ± 0.4, p < 0.0001), POD 1 (2.0 ± 0.3 vs. 4.8 ± 0.3, p = 0.0001), POD 2 (1.0 ± 0.2 vs. 3.3 ± 0.2, p < 0.0001), POD 3 (0.3 ± 0.2 vs. 2.5 ± 0.2, p < 0.0001), POD 4 (0.1 ± 0.2 vs. 1.4 ± 0.2, p < 0.0001), POD 5 (0.1 ± 0.2 vs. 1.0 ± 0.2, p < 0.0001), POD 6 (0.0 ± 0.1 vs. 0.6 ± 0.1, p < 0.0001), and POD 7 (0.0 ± 0.1 vs. 0.5 ± 0.1, p < 0.001; Fig. 2A). Postoperative VAS pain score on movement was also significantly lower in the SLG group than in the MLG group 6 h after surgery (4.1 ± 0.3 vs. 7.4 ± 0.4, p < 0.0001), POD 1 (3.3 ± 0.3 vs. 5.9 ± 0.3, p = 0.0001), POD 2 (2.4 ± 0.3 vs. 4.9 ± 0.3, p < 0.0001), POD 3 (1.4 ± 0.2 vs. 4.3 ± 0.3, p < 0.0001), POD 4 (0.6 ± 0.2 vs. 3.3 ± 0.2, p < 0.0001), POD 5 (0.3 ± 0.2 vs. 2.5 ± 0.2, p < 0.0001), POD 6 (0.1 ± 0.1 vs. 1.9 ± 0.2, p < 0.0001), and POD 7 (0.1 ± 0.2 vs. 1.4 ± 0.2, p < 0.001; Fig. 2B). In the SLG group, pain at rest improved rapidly on POD 3 and was almost fully alleviated (VAS score 0.2), and pain at movement resolved on POD 4 (VAS score 0.6). In the MLG group, resolution of pain at rest was slow (VAS score 0.6 on POD 6) and there was still pain on the date of discharge (VAS score 1.4 on POD 7). Analgesics were administered significantly less often in the SLG group than in the MLG group (1 [0–15] vs. 3 [0–14], p = 0.0078) and the duration of use of analgesics was significantly shorter in the SLG group (2 [0–6] days vs. 3 [0–9] days, p = 0.0171).

When pain was evaluated for four area (umbilical, upper abdomen, right abdomen, left abdomen), the pain was significantly lower in the SLG group than that in the MLG group for each area. The SLG group had almost or no pain in the right or left abdomen (mean VAS score 0.0–0.1), whereas the MLG group had pain in the right abdomen on the day of surgery and on PODs 1 and 2 (VAS scores 2.5 ± 0.5, 1.5 ± 0.3, and 1.1 ± 0.2, respectively) but almost no pain on POD 3 (VAS score 0.8 ± 0.2). The MLG group had pain in the left abdomen on the day of surgery and on POD 1 (VAS scores 3.4 ± 0.5 and 1.8 ± 0.3, respectively) but almost no pain on POD 2 (VAS score 0.9 ± 0.2). There was not significant difference between the left abdomen and right abdomen (p = 0.417 on POD 1). Pain was significantly less severe in the SLG group than in the MLG group postoperatively when evaluated in the umbilical portion (VAS score in SLG vs. MLG: 2.7 ± 0.3 vs. 6.2 ± 0.5, p < 0.0001 on the day of surgery, 1.8 ± 0.2 vs. 4.3 ± 0.3, p < 0.0001 on POD 1, 0.8 ± 0.1 vs. 3.0 ± 0.3, p < 0.0001 on POD 2, 0.2 ± 0.1 vs. 2.3 ± 0.3, p < 0.0001 on POD 3) and upper abdomen (VAS score in SLG vs. MLG: 2.7 ± 0.3vs. 6.2 ± 0.5, p < 0.0001 on the day of surgery, 0.6 ± 0.2 vs. 3.4 ± 0.6, p = 0.0001 on POD 1, 0.2 ± 0.1 vs. 1.8 ± 0.3, p = 0.0115 on POD 2, 0.2 ± 0.1 vs. 1.1 ± 0.3, p = 0.0198 on POD 3).

Long-term outcomes

Patients were followed for 31.7 (range 18.1–45.7) months postoperatively, corresponding to 31.7 (range 18.1–43.9) months in the SLG group and 31.6 months (range 18.8–45.7) in the MLG group (p = 0.380). Relapse-free survival was similar in the SLG and MLG groups (100% vs. 100%). No patients suffered from umbilical hernias in both groups during the follow-up periods.

Discussion

This is the first randomized controlled trial to compare the outcomes of single-port laparoscopic gastrectomy (SLG) and multi-port laparoscopic gastrectomy (MLG) for the treatment of gastric cancer. The primary goal of the study was to demonstrate the effectiveness of SLG in reducing postoperative pain. The results clearly show that the postoperative VAS pain score was significantly lower after SLG than after MLG both at rest and on movement. Furthermore, the SLG group required less additional analgesia than the MLG group and had a shorter duration of use of analgesia. The benefit of SLG was shown to be associated with a reduced postoperative pain profile.

Three short-term studies have compared the outcomes, including postoperative pain, between SLG and MLG for relatively early gastric cancer [14, 15]. All studies were retrospective analyses of prospectively collected SLG and MLG data. However, a literature search did not identify any relevant prospective randomized studies. A case-matched comparative study by Ahn et al. showed that SLG with D1 + lymphadenectomy was associated with a lower VAS score on the day of surgery and POD 1 compared with MLG [14]. In another study, SLG with D2 lymphadenectomy was associated with less frequent use of analgesia compared with MLG [15]. In contrast, a study by Kim et al. found no significant between-group differences in postoperative VAS pain scores [18]. Therefore, the efficacy of SLG is controversial, and there is no confirmatory data from previously published randomized controlled trials.

Postoperative pain is an important consideration when evaluating the efficacy of a surgical approach considering that a lower pain level can allow earlier ambulation and aid a fast-track protocol. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing conventional care with fast-track care in patients who had undergone laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer found that the fast-track groups had a shorter hospital stay, a shorter time to flatus, and a lower C-reactive protein level [27]. In a prospective randomized controlled study of the efficacy of SLG in the treatment of morbid obesity, reduction of pain on movement was found to be more important than that at rest because it contributed to early mobilization [28]. In our study, we found that patients who underwent SLG had less postoperative pain on the day of surgery and on PODs 1–7 than those who underwent MLG. Pain at rest improved rapidly and was almost completely resolved by POD 3 in the SLG group (VAS score 0.2) but improved more slowly and was not fully relieved until POD 6 in the MLG group. The pain profile on movement was similar in that pain was relieved earlier in the SLG group (on POD 4), but the pain remained on the day of discharge in the MLG group. There was no significant difference in bowel recovery, postoperative inflammatory reaction, or postoperative hospital stay between the two groups, mainly because the same clinical pathway was used. However, this rapid improvement of pain in patients who receive SLG may lead to earlier ambulation, shorter leave of absence from work, and better quality of life.

Earlier pain relief in our SLG group can be attributed to reduced parietal pain as a result of fewer incisions in the abdominal wall. These incisions can be painful as a result of trauma alone or because of the fascial tension caused by closure. Pain was assessed at four sites: the umbilicus, upper abdomen, right abdomen, and left abdomen, and VAS pain score at each site was significantly lower in the SLG group than in the MLG group. The SLG group had little or no pain in the right and left abdomen (mean VAS score 0.0–0.1), whereas the MLG group had pain in the left and right abdomen on POD 1 (VAS scores 1.5 ± 0.3 and 1.8 ± 0.3, respectively). There was not significant difference between the left abdomen and right abdomen. This suggests that both the 5-mm and 12-mm trocars produced constant pain, and that differences in trocar diameter did not affect postoperative pain. Interestingly, in the present study, pain in the upper abdomen, where no incision was made, was significantly less in the SLG group than in the MLG group. Upper abdominal pain may be associated with visceral pain in response to gastric mobilization and peripancreatic lymphadenectomy. Because of the limited number of forceps that can be used in SLG, supra-pancreatic lymph node dissection must be performed meticulously without pressing and retracting the pancreas or other visceral organs. These procedures attenuate postoperative damage and may account for the reduction in pain after SLG.

SLG is technically difficult due to absence of triangulation, collision of the surgical instruments used, and lack of counter traction. Nevertheless, the operating time is reportedly similar for SLG and MLG even when performing D2 gastrectomy [14, 15, 17, 18]. Furthermore, in the present study, we found that the operating time was significantly shorter in the SLG group (169 min) than in the MLG group (182 min) without any significant difference in blood loss. We have experienced about 500 single-port gastrectomy for gastric cancers, so the procedures have been completely standardized [16]. The time for intracorporeal procedures such as gastric mobilization, lymph node dissection, and reconstruction, was not significantly different between two groups (data not shown). MLG had a higher number of ports than SLG and required additional time for procedures such as trocar insertion and wound closure at the trocar site. Beneficial effect of SLG is a shortened operative time with minimal skin incision.

A multi-institutional prospective study reported an overall postoperative complication rate of 9.1–13.0% and a severe complication rate (grade III or higher) of 3.6–5.1% with multi-port laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for relatively early gastric cancer [5, 29]. An overall complication rate of 12–20.8% and a severe complication rate of 5.0–5.1% have been reported with single-port laparoscopic distal gastrectomy [14, 18]. A previous study in patients with advanced gastric cancer found that the complication rate was lower for SLG than for MLG [17]. In our study, the overall postoperative complication rate was similar in the SLG and MLG groups (8% vs. 11.8%) and lower than that in previous reports (12–20.8%). No severe complications were observed in either group. The rate of Clavien–Dindo grade II intra-abdominal complications, such as intra-abdominal abscess and delayed gastric emptying, tended to be lower in the SLG group (0%) than in the MLG group (4%). These results suggest that SLG is safe and feasible.

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the data. First, although the patient characteristics were well balanced, there were more patients with D2 gastrectomy in the SLG group than in the MLG group. However, operative time was shorter in the SLG group than in the MLG group, and the short-term surgical outcomes were comparable between the study groups. Second, we did not evaluate the total amount of analgesia used when assessing postoperative pain. In our study, additional analgesics, such as NSAIDs, were administered at the patient's request. The type of analgesia administered was determined by physician choice. It was difficult to compare the amount of analgesia administered between two groups because the type of analgesic administered varied from patient to patient. Therefore, instead of this assessment, we evaluated the frequency of analgesic administration and the duration of analgesic use. Thirdly, the long-term outcomes could not be clearly evaluated because the follow-up period was too short. We are planning to evaluate long-term outcomes in this cohort once the follow-up period reaches five years. Finally, the study had an open-label design and a small sample size. The patients who underwent the SLG group might have reported much less pain because of their satisfaction for small scar. So, a large-scale, multicenter, double-blind randomized controlled study is needed to confirm the feasibility and efficacy of the single-port approach.

Conclusions

When compared with our MLG group, our SLG group had less postoperative pain, a shorter operating time, and a more acceptable morbidity rate. These findings suggest that SLG is safe and feasible for patients with cStage I gastric cancer. Specifically, SLG is less invasive, causes minimal scarring, and allows rapid postoperative recovery. SLG may be an attractive minimally invasive option for the treatment of gastric cancer. Multicenter, large-scale prospective randomized trials are required to confirm its feasibility and effectiveness.

References

Kitano S, Iso Y, Moriyama M, Sugimachi K (1994) Laparoscopy-assisted Billroth I gastrectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc 4:146–148

Kitano S, Shiraishi N, Fujii K, Yasuda K, Inomata M, Adachi Y (2002) A randomized controlled trial comparing open vs laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for the treatment of early gastric cancer: an interim report. Surgery 131:S306–S311

Katai H, Mizusawa J, Katayama H, Takagi M, Yoshikawa T, Fukagawa T, Terashima M, Misawa K, Teshima S, Koeda K, Nunobe S (2017) Short-term surgical outcomes from a phase III study of laparoscopy-assisted versus open distal gastrectomy with nodal dissection for clinical stage ia/ib gastric cancer: Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study JCOG0912. Gastric Cancer 20:699–708

Viñuela EF, Gonen M, Brennan MF, Coit DG, Strong VE (2012) Laparoscopic versus open distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and high-quality nonrandomized studies. Ann Surg 255:446–456

Han SU, Kim MC, Hyung WJ, Ryu SW, Cho GS, Kim CY, Yang HK, Park DJ, Kim W, Kim HH, Ong KY, Lee SI, Ryu SY, Lee JH, Lee HJ, Korean Laparo-endoscopic Gastrointestinal Surgery Study (KLASS) Group (2016) Decreased morbidity of laparoscopic distal gastrectomy compared with open distal gastrectomy for stage I gastric cancer: short-term outcomes from a multicenter randomized controlled trial (KLASS-01). Ann Surg 263:28–35

Kim YW, Baik YH, Yun YH, Nam BH, Kim DH, Choi IJ, Bae JM (2008) Improved quality of life outcomes after laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: results of a prospective randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg 248:721–727

Ziqiang W, Feng Q, Zhimin C, Miao W, Lian Q, Huaxing L, Peiwu Y (2006) Comparison of laparoscopically assisted and open radical distal gastrectomy with extended lymphadenectomy for gastric cancer management. Surg Endosc 20:1738–1743

Hwang SI, Kim HO, Yoo CH, Shin JH, Son BH (2009) Laparoscopic-assisted distal gastrectomy versus open distal gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer. Surg Endosc 23:1252–1258

Katai H, Mizusawa J, Katayama H, Morita S, Yamada T, Bando E, Ito S, Takagi M, Takagane A, Teshima S, Koeda K, Nunobe S, Yoshikawa T, Terashima M, Sasako M (2020) Survival outcomes after laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy versus open distal gastrectomy with nodal dissection for clinical stage IA or IB gastric cancer (JCOG0912): a multicentre, non-inferiority, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 5:142–151

Kim HH, Han SU, Kim MC, Kim W, Lee HJ, Ryu SW, Cho GS, Kim CY, Yang HK, Park DJ, Song KY, Lee SI, Ryu SY, Lee JH, Hyung WJ, Korean Laparoendoscopic Gastrointestinal Surgery Study (KLASS) Group (2019) Effect of laparoscopic distal gastrectomy vs open distal gastrectomy on long-term survival among patients with stage I gastric cancer: the KLASS-01 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 5:506–513

Omori T, Oyama T, Akamatsu H, Tori M, Ueshima S, Nishida T (2011) Transumbilical single-incision laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer. Surg Endosc 25:2400–2404

Park DJ, Lee J-H, Ahn SH, Eng AKH, Kim H-H (2012) Single-port laparoscopic distal gastrectomy with D1+β lymph node dissection for gastric cancers: report of 2 cases. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 22:e214–e216

Omori T, Masuzawa T, Akamatsu H, Nishida T (2014) A simple and safe method for Billroth I reconstruction in single-incision laparoscopic gastrectomy using a novel intracorporeal triangular anastomotic technique. J Gastrointest Surg 18:613–616

Ahn SH, Son SY, Jung DH, Park DJ, Kim HH (2014) Pure single-port laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: comparative study with multi-port laparoscopic distal gastrectomy. J Am Coll Surg 219:933–943

Omori T, Fujiwara Y, Moon J, Sugimura K, Miyata H, Masuzawa T, Kishi K, Miyoshi N, Tomokuni A, Akita H, Takahashi H (2016) Comparison of single-incision and conventional multi-port laparoscopic distal gastrectomy with D2 lymph node dissection for gastric cancer: a propensity score-matched analysis. Ann Surg Oncol 23:817–824

Omori T, Nishida T (2014) Distal gastrectomy. In: Mori T, Dapri G (eds) Reduced port laparoscopic surgery. Springer, Tokyo, pp 183–195

Omori T, Fujiwara Y, Yamamoto K, Yanagimoto Y, Sugimura K, Masuzawa T, Kishi K, Takahashi H, Yasui M, Miyata H, Ohue M, Yano M, Sakon M (2019) The safety and feasibility of single-port laparoscopic gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer. J Gastrointest Surg 23:1329–1339

Kim SM, Ha MH, Seo JE, Kim JE, Choi MG, Sohn TS, Bae JM, Kim S, Lee JH (2016) Comparison of single-port and reduced-port totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for patients with early gastric cancer. Surg Endosc 30:3950–3957

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA (2004) Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 240:205–213

Japanese Gastric Cancer Association (2011) Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma 3rd English Edition. Gastric Cancer 14(101–112):17

Omori T, Tanaka K, Tori M, Ueshima S, Akamatsu H, Nishida T (2012) Intracorporeal circular-stapled billroth I anastomosis in single-incision laparoscopic distal gastrectomy. Surg Endosc 26:1490–1494

Ushimaru Y, Omori T, Fujiwara Y, Yanagimoto Y, Sugimura K, Yamamoto K, Moon JH, Miyata H, Ohue M, Yano M (2019) The feasibility and safety of preoperative fluorescence marking with indocyanine green (ICG) in laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer. J Gastrointest Surg 23:468–476

Hamabe A, Omori T, Tanaka K, Nishida T (2012) Comparison of long-term results between laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy and open gastrectomy with D2 lymph node dissection for advanced gastric cancer. Surg Endosc 26:1702–1709

Omori T, Oyama T, Mizutani S, Tori M, Nakajima K, Akamatsu H, Nakahara M, Nishida T (2009) A simple and safe technique for esophagojejunostomy using the hemidouble stapling technique in laparoscopy-assisted total gastrectomy. Am J Surg 197:e13–e17

Omori T, Nakajima K, Nishida T, Uchikoshi F, Kitagawa T, Ito T, Matsuda H (2005) A simple technique for circular-stapled billroth I reconstruction in laparoscopic gastrectomy. Surg Endosc 19:734–736

Omori T, Oyama T, Akamatsu H, Tori M, Ueshima S, Nakahara M, Toshirou N (2010) A simple and safe method for gastrojejunostomy in laparoscopic distal gastrectomy using the hemidouble-stapling technique: efficient purse-string stapling technique. Dig Surg 26:441–445

Liu Q, Ding Li, Jiang H, Zhang C, Jin J (2018) Efficacy of fast track surgery in laparoscopic radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Surg 50:28–34

Morales-Conde S, del Agua IA, Moreno AB, Macías MS (2017) Postoperative pain after conventional laparoscopic versus single-port sleeve gastrectomy: a prospective, randomized, controlled pilot study. Surg Obes Relat Dis 13:608–613

Katai H, Sasako M, Fukuda H, Nakamura K, Hiki N, Saka M, Yamaue H, Yoshikawa T, Kojima K, JCOG Gastric Cancer Surgical Study Group (2010) Safety and feasibility of laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy with suprapancreatic nodal dissection for clinical stage I gastric cancer: a multicenter phase II trial (JCOG 0703). Gastric Cancer 13:238–244

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

Drs. Takeshi Omori, Kazuyoshi Yamamoto, Hisashi Hara, Naoki, Shinno, Masaaki Yamamoto, Keijirou Sugimura, Hiroshi Wada, Hidenori Takahashi, Masayoshi Yasui, Hiroshi Miyata, Masayuki Ohue, Masahiko Yano, and Masato Sakon have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Omori, T., Yamamoto, K., Hara, H. et al. A randomized controlled trial of single-port versus multi-port laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Surg Endosc 35, 4485–4493 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-020-07955-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-020-07955-0