Abstract

Introduction

Even though acute appendicitis is the most common general surgical condition encountered during pregnancy, the preferred approach to appendectomy in pregnant patients remains controversial. Current guidelines support laparoscopic appendectomy as the treatment of choice for pregnant women with appendicitis, regardless of trimester. However, recent published data suggests that the laparoscopic approach contributes to higher rates of fetal demise. Our study aims to compare laparoscopic and open appendectomy in pregnancy at a statewide population level.

Methods

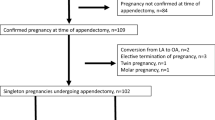

ICD-9 codes were used to extract 1006 pregnant patients undergoing appendectomy between 2005 and 2014 from the NY Statewide Planning and Research Cooperative System (SPARCS) database. Surgical outcomes (any complications, 30-day readmission rate, length of stay (LOS)) and obstetrical outcomes (antepartum hemorrhage, preterm delivery, cesarean section, sepsis, chorioamnionitis) were compared between open and laparoscopic appendectomy. Multivariable generalized linear regression models were used to compare different outcomes between two surgical approaches after adjusting for possible confounders.

Results

The laparoscopic cohort (n = 547, 54.4%) had significantly shorter LOS than the open group (median ± IQR: 2.00 ± 2.00 days versus 3.00 ± 2.00 days, p value < 0.0001, ratio = 0.789, 95% CI 0.727–0.856). Patients with complicated appendicitis had longer LOS than those with simple appendicitis (p value < 0.0001, ratio = 1.660, 95% CI 1.501–1.835). Obstetrical outcomes (p value = 0.097, OR 1.254, 95% CI 0.961–1.638), 30-day non-delivery readmission (p value = 0.762, OR 1.117, 95% CI 0.538–2.319), and any complications (p value = 0.753, OR 0.924, 95% CI 0.564–1.517) were not statistically significant between the laparoscopic versus open appendectomy groups. Three cases of fetal demise occurred, all within the laparoscopic appendectomy group.

Conclusions

The laparoscopic approach resulted in a shorter LOS. Although fetal demise only occurred in the laparoscopic group, these results were not significant (p value = 0.255). Our large population-based study further supports current guidelines that laparoscopic appendectomy may offer benefits over open surgery for pregnant patients in any trimester due to reduced time in the hospital and fetal and maternal outcomes comparable to open appendectomy.

Graphic abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

During the course of pregnancy, nearly 1/600 to 1/1000 of all pregnancies are complicated by acute appendicitis [1]. Delay in diagnosis, as well as treatment, increases the risk of perforation with an associated increase in both maternal morbidity and fetal mortality [2]. Compared to surgical intervention, conservative management has been shown to increase rates of sepsis, septic shock, and peritonitis [3]. Therefore, surgical intervention has become the mainstay of treatment. While historically performed through an open approach, the advent of laparoscopy has improved visualization of the entire abdomen allowing for improved diagnosis, decrease in post-operative pain, and shorter hospital stays [4].

Given the numerous retrospective studies that have shown laparoscopic appendectomy (LA) to be safe for both mother and child, the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) guidelines currently recommend LA as the treatment of choice for pregnant patients with acute appendicitis [5]. However, the definitive surgical approach for appendectomy during pregnancy remains unclear as some large-scale studies published since those guidelines have suggested that the laparoscopic approach contributes to higher rates of fetal demise [6, 7]. This study aims to investigate the surgical and obstetrical outcomes of patients undergoing laparoscopic versus open appendectomy (OA) in New York State.

Methods

The New York State Planning and Research Cooperative System (SPARCS) database was queried for all pregnant patients diagnosed with acute appendicitis who underwent appendectomy between 2005 and 2014. The New York SPARCS database is a comprehensive system that collects patient level data on patient demographics, diagnoses, treatments, services, and charges for inpatient and outpatient visits [8]. Approval for the assessment of outcomes following common surgical procedures in the State of New York was obtained from the Institutional Review Board. ICD-9 and CPT diagnostic and procedural codes (see Supplemental Table A) were used to extract pregnant females who were diagnosed with acute appendicitis and subsequently underwent either OA or LA. The patient cohort was also stratified by the classification of appendicitis (simple vs complicated) through diagnostic codes 540.0-541.1, 540.9, 541, 542 and procedural codes 47.2, 47.91, 47.92. Patients who had diagnostic codes for both “simple” and “other” (diagnostic codes: 543.0 and 543.9; procedural codes: 47.09, 47.9, and 47.99) appendicitis were identified as having simple appendicitis since “other” represented lymphoid hyperplasia of the appendix. In contrast, patients coded as both “complicated” and “other” appendicitis were sorted into the complicated appendicitis cohort. Exclusion criteria included males, missing identifiers, duplicate records, and patients who underwent appendectomy for causes unrelated to acute appendicitis (e.g., chronic appendicitis, incidental procedures, and appendiceal/colon neoplasm). Patients with any diagnostic code consistent with a multiple gestation pregnancy were also excluded from the study.

Patient demographics, facility type, obstetric outcomes, and surgical outcomes were stratified based on the appendicitis classification as well as the surgical approach (OA vs LA). Surgical outcomes included 30-day non-delivery readmission, appendectomy complications, and hospital length of stay (LOS). The two broad types of obstetric outcomes were fetal demise and composite maternal outcomes, which is defined as antepartum hemorrhage, chorioamnionitis, preterm delivery, sepsis, and cesarean delivery. Additionally, the data and outcomes were stratified by trimester, which was defined as a categorical variable derived from days from appendectomy to delivery. As such, first trimester is defined as a patient undergoing appendectomy within 6–10 months before delivery. Second trimester patients underwent appendectomy within 3–6 months before delivery while third trimester patients underwent appendectomy within 0–3 months before delivery.

Chi-square tests with exact p values based on Monte Carlo simulation were utilized to examine the marginal association between categorical variables with surgical approach, surgical complications, obstetric outcomes, and 30-day non-delivery readmission. Wilcoxon’s rank sum tests (for variables with 2 levels) and Kruskal–Wallis tests (for variables with 3 or more levels) were used to compare unadjusted marginal differences in LOS among different levels of categorical variables. Univariate analysis of fetal demise associated with surgical approach was conducted using Fisher’s exact test. Appendectomy surgical approach, appendicitis classification, and other significant factors related to each outcome that were significant (p value < 0.05) based on univariate analyses were further considered in multivariable logistic regression models for binary outcomes (e.g., obstetric outcomes, 30-day non-delivery readmission rate, and surgical complications). Firth bias correction was used if there is semi-separation issue because of data sparsity. Generalized linear regression model was used to compare LOS assuming it followed a negative binomial distribution and any complication was used in this model instead of specific complications since most complications were significantly associated with LOS. Statistical significance was set at 0.05 and analysis was performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Out of the 1,488,190 singleton deliveries that were identified from the inpatient SPARCS dataset, a total of 1,006 pregnant patients who underwent appendectomy for acute appendicitis between 2005 and 2014 formed the study cohort. 459 (45.63%) patients underwent OA while 547 (54.37%) patients underwent LA. Patients of both the OA and LA cohorts were a median age of 27 years old. As shown in Table 1, there was no statistically significant difference between the two cohorts in terms of age, race/ethnicity, state region, or alcohol and tobacco use. LA was more likely to be performed at academic centers (60.23% vs 48.16%; p < 0.0001) while OA was more likely to be performed at community centers (51.84% vs 39.77%; p < 0.0001).

Clinical information pertaining to the patients’ comorbidities, type of appendicitis, trimester, LOS, surgical complications, and 30-day non-delivery readmission is shown in Table 2. Apart from hypothyroidism, rheumatoid arthritis, and depression, both groups were not statistically different in respect to their comorbidities at the time of surgery. While a majority of the cases were classified as simple appendicitis, 141 (14.02%) patients were diagnosed with complicated appendicitis of which LA was performed in 65 (46.10%) patients, while OA was performed in 76 (53.90%) patients. Additionally, the rate of LA and OA differed between the trimesters with a preference for LA in the first and second trimester but a shift to favoring OA in the third trimester. Patients with LA had a LOS that was one day shorter than the OA group (median ± IQR: 2.00 ± 2.00 days versus 3.00 ± 2.00; p < 0.0001). There were no marked differences in surgical complications or 30-day non-delivery related readmissions between the women who had their operation using the laparoscopic or open approach. Only 34 (3.38%) patients had to be readmitted to the hospital following their initial appendectomy for a non-delivery reason of which 16 (47.06%) had a LA and 18 (52.94%) had an OA.

Table 3 highlights the obstetric outcomes of OA and LA patients, respectively. Two broad types of obstetric outcomes, fetal demise and composite maternal outcomes, were measured and stratified by type of appendectomy (LA vs OA) and type of appendicitis (simple vs complicated). Based on this classification, 3 out of 1,006 patients had fetal demise all occurring after LA. One (0.10%) of these patients had complex appendicitis while the remaining 2 (0.20%) cases had simple appendicitis. None of the OA cases, regardless of being complicated or simple appendicitis, had reported fetal deaths. Of note, there was no statistical difference in the frequency of fetal demise when comparing the two surgical approaches (p value = 0.255). Because of low frequency of fetal demise, no multivariable regression model was built for this outcome.

Complicated appendicitis more frequently resulted in at least one of the measured adverse composite maternal outcomes, regardless of the type of surgical approach. For example, in the LA group, 52.31% of patients with complicated appendicitis had at least one composite maternal outcome while 47.93% of patients with simple appendicitis had at least one composite maternal outcome. Similarly, in the OA group, 54.17% of patients with complicated appendicitis had at least one composite maternal outcome while 44.39% of patients with simple appendicitis had at least one composite maternal outcome. The frequencies of the 5 specific maternal outcomes are further shown in Table 4.

The results of the multivariable logistic regression analyses to identify independent predictors of LOS, surgical complications, 30-day non-delivery readmission, and obstetric outcomes are shown in Tables 5, 6, 7 and 8. Interaction between type of appendectomy and appendicitis (not reported in Tables 5, 6, 7 and 8) were non-significant in all 4 regression models. From the 4 regression models, LOS was significantly different when comparing type of appendectomy, appendicitis, and across the trimesters. Patients who underwent LA had a shorter LOS than those who underwent OA (ratio: 0.789, 95% CI 0.727–0.856; p value: < 0.001) and patients with complicated appendicitis had a longer LOS than those with simple appendicitis (ratio: 1.660, 95% CI 1.501, 1.835; p value: < 0.001). Complicated appendicitis was also associated with an increased risk for surgical complications when compared to simple appendicitis (OR 5.680, 95% CI 3.421, 9.390; p value: < 0.0001). With respect to the timing of antepartum appendectomy, patients who underwent surgery during the first and second trimester both had shorter LOS than those who underwent surgery during the third trimester (1st trimester vs 3rd trimester ratio: 0.761, 95% CI 0.683–0.848; and 2nd trimester vs 3rd ratio: 0.853, 95% CI 0.771–0.942; p value: < 0.0001). 30-day non-delivery readmission was significantly different between trimesters with a lower likelihood for readmission in the first trimester when compared to the third trimester (OR 0.211, 95% CI 0.067–0.578; p = value: 0.0132). The remaining regression model for obstetric outcomes did not show any outcome difference among the types of surgical approaches, appendicitis, or trimester.

Discussion

While the safety and efficacy of LA [9,10,11] has been established in the non-pregnant population, the safety and utility of this surgical approach in the pregnant patient remains controversial. Although multiple single-institution studies and case series with a small sample size have demonstrated the efficacy of this surgical approach with regards to maternal and fetal outcomes [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19], there have been systematic reviews, a meta-analysis, and a large population-based study [6, 7, 20,21,22] that have suggested that the laparoscopic approach leads to increased rates of fetal demise. To our knowledge, our population-based analysis utilizing the NY SPARCS database from 2005 to 2014 is one of the largest studies to date.

Our results point to an interesting dichotomy between the preferred surgical method when stratified by facility type in NY state. While academic centers performed a higher percentage of LA compared to the open approach, the inverse was true for community-based practices. One may attribute this difference to the two pivotal changes that occurred in 2009—the Affordable Care Act being passed into law and the American Board of Surgery’s incorporation of Fundamentals of Laparoscopic Surgery into General Surgery board certification. To understand if these factors possibly affected surgeons’ preference, an analysis looking at the interaction between surgery type and time period pre-2009 and post-2009 was carried out. As demonstrated in Table 9, the p values for this interaction from all four multivariable regression models are > 0.05 suggesting that there was no statistically significant difference in surgical or obstetrical outcomes when stratified by time period. A potential reason for this dichotomy between community and academic surgeons may be due to the fact that community surgeons may have perceived OA to be more affordable without being clinically inferior to LA [23]. In contrast, academic institution-based surgeons may have been quicker to adopt laparoscopy in pregnant patients due to their familiarity with the technique. Further studies looking at the adaptation of laparoscopic techniques as it relates to unique populations like pregnant patients are needed.

When looking at the two surgical approaches in pregnant patients with appendicitis, our results demonstrate that the laparoscopic approach leads to a decreased hospital length of stay compared to patients undergoing open appendectomy. Similarly, Cheng et al. who conducted a large population-based analysis from Taiwan’s National Health Research Institutes database noted a significantly longer hospital stay for the OA group compared to the LA group (mean: 5.5 days vs 3.8 days) [24]. Conventional advantages to a shortened hospital stay seen in the non-pregnant population (i.e., quicker return to daily-activities, reduced immobilization, and decreased cost) can also be applied to the pregnant population. Additionally, we found other factors that could affect a pregnant woman’s LOS after appendectomy, including the severity of appendicitis and timing of operation. Patients with complicated appendicitis (i.e., perforation, abscess, fecal peritonitis, etc.) had a longer hospital stay, regardless of surgical approach. And, LOS increased as the patient’s gestational age increased. Compared to first and second trimester patients, third trimester patients are often kept under extended periods of observation to monitor for signs of preterm labor or other complications which may explain this trend.

Interestingly, when the type of surgical method was stratified by trimester, there was a statistically significant shift from utilizing the laparoscopic approach in the first and second trimesters to favoring an open approach in the third trimester. This trend can be explained in part by three major concerns with the laparoscopic approach and its utility in later trimesters. They include the gravid uterus, increased intraabdominal pressure resulting in decreased venous return, and fetal acidosis during carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum [25]. A larger gravid uterus, especially in the later trimesters of pregnancy, increases the risk of uterine injury when inserting the insufflating needle without visualization [26]. To ameliorate this, a Veress needle can be inserted under the guidance of ultrasound visualization or be placed at an alternative site (e.g., Palmer Point) to the conventional periumbilical position [25]. Next, critics claim that the pneumoperitoneum created for visualization compromises venous return and maternal cardiac output. This obstacle can be addressed by placing the patient in a Trendelenburg or left lateral decubitus position to increase venous return while also maintaining intraabdominal pressures below 15 mmHg [25]. With regards to the adverse effect of fetal acidosis following maternal CO2 absorption, studies have demonstrated that laparoscopy has little effect on the acid–base status of maternal blood [27]. Furthermore, in animal studies, there were no reported adverse effects in the fetuses of pregnant ewes that were insufflated with CO2 to pressures as high as 10–12 mmHg [28].

In fact, our results suggest that surgical complications resulting from appendectomy in pregnancy are not due to the surgical approach or timing of antepartum operation. Rather, surgical complications arise based on the complexity of the patient’s underlying illness. Those with complicated appendicitis had over a fivefold greater likelihood to have a surgical complication than those with simple appendicitis. This can possibly be explained by the unique challenges that an appendiceal perforation, abscess formation, or fecal peritonitis pose intraoperatively as the dissection planes become distorted by extensive inflammation or the ensuing infectious complications that arise in the post-operative period.

An important consideration for selecting a surgical approach in the pregnant population is accounting for both maternal and fetal outcomes mentioned above. While McGory et al. report a significantly higher fetal loss following LA versus the open approach, the reported fetal outcomes in their study were limited to the same hospitalization as the appendectomy. As a result, their study fails to account for fetal outcomes that occurred following hospitalization for appendectomy or during a readmission. Consequently, many of the systematic reviews that concluded LA leads to higher rates of fetal loss were dominated by the large sample size of McGory et al.’s study. Remarkably, if this study was excluded from Wilasrusmee et al.’s pooled analysis, then the association between laparoscopic appendectomy and fetal demise ceased to exist [22]. Fetal demise is also higher in early trimesters of pregnancy, when the laparoscopic approach is favored [29, 30]. This may confound analysis in these studies. In our study, there were 3 reported cases of fetal demise in all pregnant patients undergoing appendectomy in NY State from 2005 to 2014. Each of the three cases of fetal demise occurred following laparoscopic appendectomy in a different trimester. Notably, surgical approach was not statistically associated with fetal demise. Since the laparoscopic approach only decreased hospital LOS but did not increase the risk of fetal demise, adverse obstetrical and surgical outcomes, or 30-day non-delivery related readmissions, we demonstrate that LA offers a marginal advantage over the OA.

Our study has several limitations that are inherent to the NY SPARCS database. First, since our data is limited to pregnant women undergoing appendectomy in New York, our results cannot be generalized to other geographic areas. Next, diagnostic and procedural codes were utilized to query, exclude, and extract pertinent patient information from the state database. For example, those patients who were coded as being an incidental appendectomy, appendectomy for chronic appendicitis, or malignancy were excluded. Patients who were coded as having “other appendicitis” were categorized into the simple appendicitis group. Consequently, the procedural and diagnostic codes could have been miscoded, thereby potentially underestimating both frequency of complicated appendicitis and patients undergoing OA or LA. An inherent limitation to any large population database study is the inability to understand unique patient circumstances surrounding a fetal demise which an in-depth chart review affords. Future studies are needed to unearth clinical information (e.g., physical exam, gestational age, pre-existing fetal anomalies or abnormalities) that may explain cases of fetal demise and surgical complications. Despite these limitations, our population-based study is one of the largest sample size studies investigating both surgical and obstetrical outcomes following appendectomy in pregnant patients during the laparoscopic era. In addition, the NY SPARCS database allowed us to collect a large amount of patient data that would otherwise be unattainable.

While many studies have demonstrated the safety profile that laparoscopy affords in pregnant patients requiring appendectomy, systematic reviews and studies with large sample sizes have called the safety of LA into question. Our study shows that while 3 cases of fetal demise did occur in the LA group, this finding was not statistically significant. In addition to fetal outcomes, there was no difference between LA and OA in terms of surgical complications, maternal outcomes (i.e., antepartum hemorrhage, chorioamnionitis, sepsis, cesarean delivery, preterm delivery), and 30-day non-delivery readmission rates. Rather, the severity of the underlying pathology played a greater role in surgical complications. Ultimately, these findings combined with the data that LA leads to a shorter hospital stay than OA supports current SAGES guidelines that laparoscopic appendectomy is the treatment of choice for pregnant patients with acute appendicitis [5].

References

Mazze RI, Kallen B (1991) Appendectomy during pregnancy: a Swedish registry study of 778 cases. Obstet Gynecol 77:835–840

Yilmaz HG, Akgun Y, Bac B, Celik Y (2007) Acute appendicitis in pregnancy–risk factors associated with principal outcomes: a case control study. Int J Surg 5:192–197

Abbasi N, Patenaude V, Abenhaim HA (2014) Management and outcomes of acute appendicitis in pregnancy-population-based study of over 7000 cases. BJOG 121:1509–1514

Korndorffer JR Jr, Fellinger E, Reed W (2010) SAGES guideline for laparoscopic appendectomy. Surg Endosc 24:757–761

Pearl JP, Price RR, Tonkin AE, Richardson WS, Stefanidis D (2017) SAGES guidelines for the use of laparoscopy during pregnancy. Surg Endosc 31:3767–3782

McGory ML, Zingmond DS, Tillou A, Hiatt JR, Ko CY, Cryer HM (2007) Negative appendectomy in pregnant women is associated with a substantial risk of fetal loss. J Am Coll Surg 205:534–540

Walsh CA, Tang T, Walsh SR (2008) Laparoscopic versus open appendicectomy in pregnancy: a systematic review. Int J Surg 6:339–344

Chen X, Wang Y, Schoenfeld E, Saltz M, Saltz J, Wang F (2017) Spatio-temporal analysis for New York State SPARCS data. AMIA Jt Summits Transl Sci Proc 2017:483–492

Masoomi H, Mills S, Dolich MO, Ketana N, Carmichael JC, Nguyen NT, Stamos MJ (2011) Comparison of outcomes of laparoscopic versus open appendectomy in adults: data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), 2006–2008. J Gastrointest Surg 15:2226–2231

Moazzez A, Mason RJ, Katkhouda N (2011) Laparoscopic appendectomy: new concepts. World J Surg 35:1515–1518

Wei HB, Huang JL, Zheng ZH, Wei B, Zheng F, Qiu WS, Guo WP, Chen TF, Wang TB (2010) Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy: a prospective randomized comparison. Surg Endosc 24:266–269

Barnes SL, Shane MD, Schoemann MB, Bernard AC, Boulanger BR (2004) Laparoscopic appendectomy after 30 weeks pregnancy: report of two cases and description of technique. Am Surg 70:733–736

de Perrot M, Jenny A, Morales M, Kohlik M, Morel P (2000) Laparoscopic appendectomy during pregnancy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 10:368–371

Lemieux P, Rheaume P, Levesque I, Bujold E, Brochu G (2009) Laparoscopic appendectomy in pregnant patients: a review of 45 cases. Surg Endosc 23:1701–1705

Lyass S, Pikarsky A, Eisenberg VH, Elchalal U, Schenker JG, Reissman P (2001) Is laparoscopic appendectomy safe in pregnant women? Surg Endosc 15:377–379

Sadot E, Telem DA, Arora M, Butala P, Nguyen SQ, Divino CM (2010) Laparoscopy: a safe approach to appendicitis during pregnancy. Surg Endosc 24:383–389

Schreiber JH (1990) Laparoscopic appendectomy in pregnancy. Surg Endosc 4:100–102

Schwartzberg BS, Conyers JA, Moore JA (1997) First trimester of pregnancy laparoscopic procedures. Surg Endosc 11:1216–1217

Thomas SJ, Brisson P (1998) Laparoscopic appendectomy and cholecystectomy during pregnancy: six case reports. JSLS 2:41–46

Prodromidou A, Machairas N, Kostakis ID, Molmenti E, Spartalis E, Kakkos A, Lainas GT, Sotiropoulos GC (2018) Outcomes after open and laparoscopic appendectomy during pregnancy: a meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 225:40–50

Walker HG, Al Samaraee A, Mills SJ, Kalbassi MR (2014) Laparoscopic appendicectomy in pregnancy: a systematic review of the published evidence. Int J Surg 12:1235–1241

Wilasrusmee C, Sukrat B, McEvoy M, Attia J, Thakkinstian A (2012) Systematic review and meta-analysis of safety of laparoscopic versus open appendicectomy for suspected appendicitis in pregnancy. Br J Surg 99:1470–1478

Switzer NJ, Gill RS, Karmali S (2012) The evolution of the appendectomy: from open to laparoscopic to single incision. Scientifica (Cairo) 2012:895469

Cheng HT, Wang YC, Lo HC, Su LT, Soh KS, Tzeng CW, Wu SC, Sung FC, Hsieh CH (2015) Laparoscopic appendectomy versus open appendectomy in pregnancy: a population-based analysis of maternal outcome. Surg Endosc 29:1394–1399

Fatum M, Rojansky N (2001) Laparoscopic surgery during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Surv 56:50–59

Friedman JD, Ramsey PS, Ramin KD, Berry C (2002) Pneumoamnion and pregnancy loss after second-trimester laparoscopic surgery. Obstet Gynecol 99:512–513

Pucci RO, Seed RW (1991) Case report of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the third trimester of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 165:401–402

Curet MJ, Vogt DA, Schob O, Qualls C, Izquierdo LA, Zucker KA (1996) Effects of CO2 pneumoperitoneum in pregnant ewes. J Surg Res 63:339–344

Wang X, Chen C, Wang L, Chen D, Guang W, French J (2003) Conception, early pregnancy loss, and time to clinical pregnancy: a population-based prospective study. Fertil Steril 79:577–584

Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, O'Connor JF, Baird DD, Schlatterer JP, Canfield RE, Armstrong EG, Nisula BC (1988) Incidence of early loss of pregnancy. N Engl J Med 319:189–194

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the biostatistical consultation and support from the Biostatistical Consulting Core at the School of Medicine, Stony Brook University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

No industry or other external funding was used for this research. Dr. Pryor is a speaker for Ethicon, Gore, Merck, and Stryker. She participates on a scientific advisory board for Obalon. Dr. Spaniolas has research support from Merck and is a speaker for Gore. Ms. Zhang, Dr. Tumati, Dr. Yang, Dr. Su, Dr. Ward, Dr. Hong, Dr. Garry, and Dr. Talamini have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tumati, A., Yang, J., Zhang, X. et al. Pregnant patients requiring appendectomy: comparison between open and laparoscopic approaches in NY State. Surg Endosc 35, 4681–4690 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-020-07911-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-020-07911-y