Abstract

Background

Post-hepatectomy liver failure (PHLF) represents the most frequent complication after liver surgery, and the most common cause of morbidity and mortality. Aim of the study is to identify the predictors of PHLF after mini-invasive liver surgery in cirrhosis and chronic liver disease, and to develop a model for risk prediction.

Methods

The present study is a multicentric prospective cohort study on 490 consecutive patients who underwent mini-invasive liver resection from the Italian Registry of Mini-invasive Liver Surgery (I go MILS). Retrospective additional biochemical and clinical data were collected.

Results

On 490 patients (26.5% females), PHLF occurred in 89 patients (18.2%). The only independent predictors of PHLF were Albumin-Bilirubin (ALBI) score (OR 3.213; 95% CI 1.661–6.215; p < .0.0001) and presence of ascites (OR 3.320; 95% CI 1.468–7.508; p = 0.004). Classification and regression tree (CART) modeling led to the identification of three risk groups: PHLF occurred in 23/217 patients with ALBI grade 1 (10.6%, low risk group), in 54/254 patients with ALBI score 2 or 3 and absence of ascites (21.3%, intermediate risk group) and in 12/19 patients with ALBI score 2 or 3 and evidence of ascites (63.2%, high risk group), p < 0.0001. The three groups showed a corresponding increase in postoperative complications (20.0%, 27.5% and 66.7%), Comprehensive Complication Index (5.1 ± 11.1, 6.0 ± 10.9 and 18.8 ± 18.9) and hospital stay (6.0 ± 4.0, 6.0 ± 6.0 and 8.0 ± 5.0 days).

Conclusion

The risk of PHLF can be stratified by determining two easily available preoperative factors: ALBI and ascites. This model of risk prediction offers an objective instrument for a correct clinical decision-making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Liver resection (LR) is the best available curative treatment for most primary and secondary malignancies of the liver. In the past decades—thanks to technological advancements, improvements in surgical techniques and refinements in perioperative management—a dramatic reduction in post-LR morbidity and mortality has occurred [1, 2]. Despite these advancements, liver resection in cirrhotic patients may still be burdened by potentially life-threatening complications, among which post-hepatectomy liver failure (PHLF) remains the most fearsome and less effectively treated. According to recent literature PHLF may occur with an incidence that varies between 0.7 and 34% [3, 4], and is the leading cause of prolonged hospitalization, increased costs and poor long-term outcomes [5]. For this reason, several surgical and hepatological studies identified upper limits in terms of liver function and extent of resection in order to reduce the risk of PHLF, and ultimately to guide treatment decision [6,7,8,9,10,11].

The advent of mini-invasive liver surgery (MILS)—in terms of videolaparoscopic, hybrid or robotic approach—brought a revolution in the conception of what is feasible, useful and relatively riskless in hepatic surgery for cirrhotic patients. Several retrospective comparative studies and meta-analyses demonstrated that the application of mini-invasive techniques to liver surgery may strikingly reduce the risks of PHLF with respect to open surgery [12,13,14,15,16] as a consequence of reduced liver mobilization, decreased intraoperative fluid losses and minor surgical trauma [17]. These data suggest that MILS may be offered to cirrhotic patients even beyond the current guidelines (i.e., for presence of portal hypertension, abnormal bilirubin or Child–Pugh stage > A) without worsening short-term outcomes. However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have identified the independent predictors of PHLF after MILS in cirrhosis and chronic liver disease.

The primary endpoint of this study is to identify the preoperative variables that most impact on the development of PHLF after MILS in cirrhosis, and to develop a model for risk prediction. The secondary endpoints of the study are to evaluate ninety-day mortality, complication rates and length of hospital stay according to the predicted risk of PHLF.

Materials and methods

The Italian Group of MILS (I Go MILS) registry was established in 2014 with the goals to create a hub for data and projects on a national basis and to promote the diffusion and implementation of MILS programs on a national scale [18]. It is a prospective and intention-to-treat registry opened to any Italian center performing MILS, without restriction criteria based on number of procedures. The registry is based on 34 clinical variables regarding indication, intra- and postoperative course.

In this study data from all consecutive patients enrolled in the I Go Mils registry from November 2014 up to December 31th 2016 were extracted with the following inclusion criteria: presence of chronic liver disease or cirrhosis (F3–F4 according to METAVIR) at enrollment; at least one liver resection completed during the surgical procedure; conversion to open surgery was not considered an exclusion criteria. Patients enrolled in the registry but with no details about the performed procedure or the postoperative outcome, patients who resulted unresectable at exploration and patients who underwent the first step of an ALPPS were excluded.

Details on the available peri- and intraoperative data from the I Go Mils registry have been described elsewhere [18]. For the purposes of this study, a retrospective collection of additional data was requested to each participating center and included the following variables: preoperative biochemical analyses (platelet count, AST, creatinine, total bilirubin, INR, albumin), preoperative presence of ascites (detection of ascites at last radiological imaging), etiology of cirrhosis, viral status for HCV/HBV (active/suppressed), postoperative development of PHLF (graded according to the definition of the International Study Group of Liver Surgery, ISGLS [19]) and 90-day mortality. The deadline for data collection was set at December 31th 2018.

The study was formally approved at a central level by the Scientific Board of the I Go Mils registry, and at a local level by the Institutional Review Board of the Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori di Milano, Milan, Italy.

Preoperative evaluations and definitions

Clinically relevant portal hypertension (PH) was defined as the presence of esophageal varices and/or presence of ascites and/or a low platelet count (< 100 × 109/L) with associated splenomegaly [20].

The additional data collection allowed for the calculation of the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score [21] and the Albumin-Bilirubin (ALBI) grade [22].

MILS were performed within conventional guidelines and the extent of liver resection was classified according to the Brisbane 2000 terminology [23]. Major hepatectomy was defined as the resection of more than two adjacent segments of the liver. Difficulty of liver resection was graded according to a recently proposed complexity score into 3 levels: low, intermediate, and high. Low difficulty included wedge resection and left lateral sectionectomy; intermediate difficulty included anterolateral segmentectomy and left hepatectomy; high difficulty included postero-superior segmentectomy, right posterior sectionectomy, right hepatectomy, central hepatectomy, and extended left/right hepatectomy [24].

MILS included liver resections performed by pure laparoscopy, hybrid laparoscopy (hand-assisted) and robotic laparoscopy.

Postoperative outcomes

Postoperative complications were graded according to the Dindo–Clavien Classification (DCC) [25]. Moreover in this study we also assessed the Comprehensive Complication Index (CCI), a linear scale ranging from 0 to 100 integrating in a single formula all complications by severity, validated for abdominal surgery. CCI considers all complications as well as the treatment received, detaining the overall burden of a procedure [26].

Post-hepatectomy liver failure was defined as the impaired ability of the liver to maintain its synthetic, excretory, and detoxifying functions. PHLF was scaled according to the ISGLS [19] indications into three grades: Grade A: PHLF that does not require changes of the patient’s clinical management; Grade B: deviation of the patient’s clinical management that does not require invasive therapy; Grade C: PHLF mandating invasive treatments.

Postoperative mortality was registered as intraoperative, in-hospital, at 30- and at 90-days from surgery.

Statistical analysis

Conventional statistics were used for patient characteristics with median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables, or mean and standard deviation when more informative; categorical data were expressed by means of absolute numbers and percentages. Comparisons between groups were performed by means of Chi-square test for categorical variables, and by means of Kruskal–Wallis or Mann–Whitney test for continuous variables.

A small subset of patients had missing data (< 10%): Little’s test was run for categorical and continuous variables, and suggested that these data were missing completely at random (MCAR). Missing values were imputed for the purpose of the multivariable analysis using Markov Chain Monte Carlo regression imputation with five repeated imputations.

The main endpoint of the study was to identify the preoperative predictors of PHLF and to build a model for risk prediction. We considered of clinical interest the development of PHLF that required changes in the clinical management of the patient. Thus, for the purposes of the regression analysis, PHLF was transformed into a binary variable (grade 0–A: absent; grade B–C: present). A simple regression was performed on all the baseline clinical variables, including also those surgical variables (extent of hepatectomy, difficulty of liver resection, location of the nodule) that are supposed to be planned preoperatively. Then, multivariable logistic regression was performed on the variables resulted significant (at a p < 0.05) at simple regression: for composite scores sharing a common variable (i.e., ALBI and MELD that share bilirubin), only the score with the higher c-statistic (area under the receiver operator curve, AUC) was included in multivariable analysis, in order to avoid colinearity. Estimates on the imputed datasets were combined by using Rubin rules [27]. Finally, in order to identify patient groups with different “profiles of risk”, the analysis of significant risk factors at simple regression was made by means of classification and regression tree (CART) modeling, through Chi-square Automatic Interaction Detector (CHAID). CHAID analysis builds a predictive model, or tree, to help determine how variables best merge to explain the outcome in the given dependent variable [28]. For this model, continuous predictors were categorized based on considerations of model interpretability as well as statistical performance.

The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS ver. 20 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics and intraoperative variables

Among Centers that participate the I go MILS registry, 40 contributed with complete baseline and perioperative data on patients who underwent MILS within the study period fulfilling the inclusion criteria. The study population thus included 490 patients with a median number of 7.5 (IQR 2–15.5) patients per Center. For the retrospective collection of additional data, 36 Centers sent complete data for 470 patients, covering 96% of the case series.

Baseline patients characteristic are resumed in Table 1. Among 490 patients, 130 (26.5%) were female, the median age was 68.6 (IQR 61.4–74-7) years and the median BMI was 25.3 (IQR 23.3–28.1). In most patients the etiology of chronic liver disease was hepatitis C virus (263 patients, 59.0%), liver function was within Child–Pugh A score in 463 patients (94.5%) and the median MELD score was 8 (IQR 7–9). The liver parenchyma was cirrhotic in 339 (69.2%) patients, portal hypertension was present in 190 cases (38.8%) and 32 patients (6.5%) had preoperative evidence of mild ascites.

Hepatocellular carcinoma was the main indication to MILS (445 patients, 90.8%), with a median size of the largest nodule of 30 (IQR 20–40) mm. The lesions were localized on the antero-inferior segments in 397 patients (81%), being segment 6 (122 patients, 24.9%) and segment 3 (95 patients, 19.3%) the most frequent localizations.

Intraoperative characteristics are resumed in Supplementary Table 1. The surgical approach was pure laparoscopic for 438 (89.3%) patients and major hepatectomies were performed in 33 (6.7%) cases. Wedge resection was the most common procedure and had been performed in 245 (50.0%) patients. Overall, 43 MILS (8.7%) were converted to open procedures, being bleeding the main cause for conversion (15 patients, 34.8%).

The median operative time was 205 (IQR 150–270) minutes, median blood loss was 150 (IQR 50–300) mL and intraoperative red blood cell transfusions were needed in 24 cases (4.9%).

Difficulty of liver resection according to Kawaguchi [24] was low in 295 patients (60.2%), intermediate in 140 (28.6%) and high in 55 (11.2%). As shown in Supplementary Table 2, intraoperative blood losses, duration of surgery and conversion rates were significantly different across the three grades of difficulty, thus validating the proposed classification.

Postoperative outcomes

Details on postoperative outcomes for the entire patient population are summarized in Table 2. Intraoperative mortality was 0%. One patient died during hospital stay, thus 30- and 90-days mortality were 0.2% and 0.2%. Postoperative complications occurred in 116 patients (23.7%), and were graded 1 and 2 according to DCC in the majority (78.4%) of cases; the median (IQR) and mean (± SD) CCI were 0 (0–2) and 5.8(± 11.4), respectively. PHLF grade B or C occurred in 89 patients (18.2%). The median postoperative hospital stay was 5 days (IQR 4–7).

Logistic regression and identification of risk groups for PHLF

The results of simple and multivariable logistic regression on preoperative variables related to the risk of developing PHLF grade B or C are summarized in Table 3. In particular, at multivariable logistic regression, only ALBI score (OR 3.213; 95% CI 1.661–6.215; p < 0.0001) and presence of ascites (OR 3.320; 95% CI 1.468–7.508; p = 0.004) turned to be independent predictors of PHLF.

A classification tree was then developed through Chi-square Automatic Interaction Detector (CHAID) analysis.

Again, ALBI grade and presence of ascites were retained by the model, and allowed the identification of three groups at distinct risk of developing PHLF. In particular, 217 patients identified by liver function within ALBI grade 1 were classified at low risk of PHLF (10.6%), 254 patients with an ALBI grade 2 or 3 and absence of ascites were classified at intermediate risk of PHLF (21.3%) and 19 patients with ALBI grade 2 or 3 and evidence of ascites were classified at high risk of PHLF (63.2%). The model performance was distinguished by a classification error rate of 0.04 and a C index of 0.66 (95% CI 0.59–0.73).

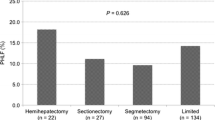

As shown in Fig. 1, the three risk groups showed significantly different postoperative complication rates, CCI and length of hospital stay. In fact, by increasing the risk class, a parallel increase in postoperative complications rates (20.0%, 27.5% and 66.7%, p < 0.0001), CCI (mean ± SD 5.1 ± 11.1, 6.0 ± 10.9 and 18.8 ± 18.9, p < 0.0001) and length of hospital stay (mean ± SD 6.0 ± 4.0, 6.0 ± 6.0 and 8.0 ± 5.0 days, p < 0.0001) was observed.

Definition of three classes of risk associated with PHLF according to ALBI grade and presence of ascites. a Patients’ partition according to PHLF risk classes. b ALBI grade and preoperative presence of ascites led to the identification of three groups at distinct risk of developing PHLF: low risk (10.6%); intermediate risk (23%) and high risk (65.5%). By increasing the risk classes, a parallel and significant increment in postoperative complications, CCI and mean hospital stay was demonstrated. PHLF indicates post-hepatectomy liver failure, p.o. postoperative, CCI Comprehensive Complication Index, LOS length of stay

Conversion to open surgery occurred in 14 patients of Group 1 (6.5%), 27 patients of Group 2 (10.6%) and 2 patients of Group 3 (10.5%), with no statistical difference among the three groups (p = 0.27). When excluding from analysis the 43 patients who underwent conversion to open surgery, PHLF occurred in 75 patients (16.8%); the PHLF rates were significantly different among the three groups occurring in 20 cases (9.9%), 45 cases (19.38%) and 10 cases (58.8%) of Group 1, 2 and 3, respectively (p < 0.0001). When analyzing only the 43 patients who underwent conversion to open surgery, PHLF occurred in 14 patients (32.6%) and PHLF occurred in 3 cases (21.4%), 9 cases (33.3%) and 2 cases (100%) of Group 1, 2 and 3, respectively (p = 0.05).

Finally, the proposed risk stratification was compared to other validated models for open surgery. As shown in Table 4, our model showed the highest accuracy in terms of AUC.

Discussion

Despite several advancements in operative techniques and perioperative management, PHLF may still occur after liver resection in cirrhotic patients, with a variable incidence ranging between 0.7 and 34% [3, 4]. It is the most common complication, and most fearsome one since it may result in increased costs, prolonged hospitalization and ultimately in increased postoperative mortality [5]. For this reason, current hepatological guidelines discourage liver resection in cirrhotic patients who present with portal hypertension, abnormal bilirubin or significantly impaired liver function (Child–Pugh B or C) [11]. More recent studies, based on studies on open liver surgery, identified MELD score, extension of hepatectomy, and liver stiffness as predictors of PHLF [2, 7, 8, 29], and combined these factors in order to better stratify postoperative risks and refine patient selection before liver surgery.

The advent of MILS has dramatically changed the scenario of short-term outcomes after liver surgery. Differently from the open approach, MILS requires small incisions and minimal liver mobilization, which result in a reduced section of the collateral lymphatic circulation and decreased intraoperative fluid and protein losses [17]. Several studies and meta-analyses demonstrated a reduced rate of postoperative ascites and PHLF with respect to open surgery, as a consequence of the aforementioned advantages [12,13,14,15,16]. Nonetheless, PHLF may still occur in nearly 20% [13, 30] of cirrhotic patients undergoing MILS in cirrhosis, and it is still largely unpredictable. For this reason, the present study was designed with the aim of identifying the independent predictors of PHLF in these patients.

There is a large heterogeneity in literature for what regards the definition of PHLF: in this study we adopted the definition proposed by the International Study Group of Liver Surgery (ISGLS) [19], and considered as events those liver dysfunctions requiring changes in the clinical management of the patient (grade B and C). Ninety-day mortality, complication rates and length of hospital stay were our secondary endpoints.

The study cohort was prospectively collected by a multicenter Italian registry (the I Go Mils Registry) [18], that in the present study included patients with cirrhosis and chronic liver disease from 40 Centers. Patients were mostly within Child–Pugh A; however, nearly 40% presented with clinically relevant portal hypertension and more than 50% had an ALBI grade > 1. The short-term outcomes of the entire cohort were in line with literature [31], being intraoperative mortality rate 0% and in-hospital and 90-days mortality 0.2%; the median postoperative hospital stay was 5 days (IQR 4–7). Despite these results, PHLF grade B or C was a relatively frequent complication and occurred in 89 patients (18.2%).

To explore the influence of different baseline patient characteristics on the risk of developing PHLF, a simple and multivariable logistic regression analysis was conducted on the entire cohort of 490 patients. The analysis demonstrated that ALBI grade (OR 3.21 for each point increase; 95% CI 1.66–6.21; p < 0.0001) and preoperative presence of ascites (OR 3.32; 95% CI 1.46–7.50; p = 0.004) were the only independent predictors of PHLF (Table 3). The ALBI score is an evidence-based model for assessing the severity of liver dysfunction that includes only objectively defined values, such as serum bilirubin and albumin. ALBI was demonstrated to be more accurate than the Child–Pugh score in predicting patients’ mortality, without requiring subjective determinants of liver failure, in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma [22]. Moreover, in a recent large cohort study, ALBI grade 2/3 turned to be independently associated with the risk of developing PHLF following hepatic resection [32]. On the other side the presence of ascites is a reflection of a decompensated cirrhosis, and not surprisingly its presence is reflected in a higher rate of postoperative liver decompensation.

In order to better stratify the risk of developing PHLF, we evaluated the baseline patients characteristics by means of classification and regression tree (CART). Again, ALBI grade and presence of ascites turned to independently predict the risk of PHLF, and allowed the identification of three risk classes: patients with an ALBI grade = 1 had a low risk of PHLF of 10.6%; patients with an ALBI grade = 2/3 and absence of ascites had an intermediate risk of PHLF of 21.3%; patients with an ALBI grade = 2/3 and presence of ascites had a high risk of PHLF of 63.2% (p < 0.0001 among the three risk classes). In the last group of patients (ALBI grade = 2/3 and presence of ascites) alternative treatments, i.e., locoregional or chemotherapeutic therapies, might be evaluated in order to avoid the high risk of PHLF and postoperative complications (66.7%) that might cause prolonged hospital stay and augmented costs.

It is interesting to observe that intraoperative blood loss, length of surgery and conversion rates were similar among the three risk classes: the different PHLF rates were likely related to baseline liver function rather than to intraoperative courses. As expected, patients who underwent conversion to open surgery had a higher rate of PHLF than patients who had the entire procedure by means of MILS (32.6% vs 16.8%, respectively), but the risk stratification was effective independently from this event.

By increasing the risk class, a parallel increase in postoperative complications rates, CCI and length of hospital stay was observed. These differences reflect the important weight of PHLF on postoperative course, and make the proposed classification a useful and objective instrument for prediction of short-term prognosis.

This study has some limitations. Firstly, in the present series there were a small number of major hepatectomies that were likely performed in very well selected cases. This may be among the reasons why the extent of hepatectomy did not turn out to be correlated with the risk of PHLF. Larger studies including a higher number of major hepatectomies are needed to analyze their impact on postoperative outcomes, and will be probably feasible in the next few years following a larger implementation of the technique.

Secondly, we collected only morbidity and mortality occurring within the first three months from surgery, because long-term outcomes were outside the study purposes. The intentional choice of 90-day follow up is based on the idea that at the PHLF resolution liver function and patient status return to the preoperative baseline. However, even if PHLF effective has a negative influence on postoperative survival, long-term outcomes may be influenced by many other factors especially in oncologic patients (that constituted 96.3% of the case series). Finally the proposed risk stratification was not externally validated. However, the model performance was distinguished by a classification error rate of 0.04 and a C index of 0.66 (95% CI 0.59–0.73), higher than previously proposed models.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that the risk for PHLF after MILS can be accurately assessed before surgery by assessing ALBI grade and preoperative presence of ascites. Both these variables are easy to define before surgery and can provide a practical method to stratify cirrhotic patients at risk of PHLF.

Abbreviations

- PHLF:

-

Post-hepatectomy liver failure

- MILS:

-

Mini-invasive liver surgery

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- CCC:

-

Mass-forming cholangiocarcinoma

- ALBI:

-

Albumin-Bilirubin score

- LR:

-

Liver resection

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- CART:

-

Classification and regression tree analysis

- ALPPS:

-

Associating liver partitioning and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy

- ISGLS:

-

International Study Group of Liver Surgery

- PH:

-

Portal hypertension

- MELD:

-

Model for end-stage liver disease

- DCC:

-

Dindo–Clavien classification

- CCI:

-

Comprehensive Complication Index

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- AUC:

-

Area under curve

- MCAR:

-

Missing completely at random

- CHAID:

-

Chi-square automatic interaction detector

References

Silberhumer GR, Paty PB, Temple LK et al (2015) Simultaneous resection for rectal cancer with synchronous liver metastasis is a safe procedure. Am J Surg 209:935–942

Sposito C, Di Sandro S, Brunero F et al (2016) Development of a prognostic scoring system for resectable hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 22:8194–8202

Lafaro K, Buettner S, Maqsood H et al (2015) Defining post hepatectomy liver insufficiency: where do we stand? J Gastrointest Surg 19:2079–2092

van den Broek MA, Olde Damink SW, Dejong CH et al (2008) Liver failure after partial hepatic resection: definition, pathophysiology, risk factors and treatment. Liver Int 28:767–780

Skrzypczyk C, Truant S, Duhamel A et al (2014) Relevance of the ISGLS definition of posthepatectomy liver failure in early prediction of poor outcome after liver resection: study on 680 hepatectomies. Ann Surg 260:865–870

EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines (2012) management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 56:908–943

Citterio D, Facciorusso A, Sposito C et al (2016) Hierarchic interaction of factors associated with liver decompensation after resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. JAMA Surg 151:846–853

Delis SG, Bakoyiannis A, Biliatis I et al (2009) Model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score, as a prognostic factor for post-operative morbidity and mortality in cirrhotic patients, undergoing hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma. HPB (Oxford) 11:351–357

Nanashima A, Abo T, Arai J et al (2013) Functional liver reserve parameters predictive for posthepatectomy complications. J Surg Res 185:127–135

Zou H, Yang X, Li QL et al (2018) A comparative study of albumin-bilirubin score with child-pugh score, model for end-stage liver disease score and indocyanine green R15 in predicting posthepatectomy liver failure for hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Dig Dis 36:236–243

European Association for the Study of the Liver (2018) EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 69:182–236

Morise Z, Ciria R, Cherqui D et al (2015) Can we expand the indications for laparoscopic liver resection? A systematic review and meta-analysis of laparoscopic liver resection for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and chronic liver disease. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 22:342–352

Sposito C, Battiston C, Facciorusso A et al (2016) Propensity score analysis of outcomes following laparoscopic or open liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Surg 103:871–880

Han HS, Shehta A, Ahn S et al (2015) Laparoscopic versus open liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: case-matched study with propensity score matching. J Hepatol 63:643–650

Aldrighetti L, Guzzetti E, Pulitano C et al (2010) Case-matched analysis of totally laparoscopic versus open liver resection for HCC: short and middle term results. J Surg Oncol 102:82–86

Cheung TT, Dai WC, Tsang SH et al (2016) Pure laparoscopic hepatectomy versus open hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma in 110 patients with liver cirrhosis: a propensity analysis at a single center. Ann Surg 264:612–620

Morise Z (2015) Perspective of laparoscopic liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastrointest Surg 7:102–106

Aldrighetti L, Ratti F, Cillo U et al (2017) Diffusion, outcomes and implementation of minimally invasive liver surgery: a snapshot from the I Go MILS (Italian Group of Minimally Invasive Liver Surgery) Registry. Updates Surg 69:271–283

Rahbari NN, Garden OJ, Padbury R et al (2011) Posthepatectomy liver failure: a definition and grading by the International Study Group of Liver Surgery (ISGLS). Surgery 149:713–724

Bruix J, Sherman M (2011) Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology 53:1020–1022

Malinchoc M, Kamath PS, Gordon FD et al (2000) A model to predict poor survival in patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Hepatology 31:864–871

Johnson PJ, Berhane S, Kagebayashi C et al (2015) Assessment of liver function in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a new evidence-based approach-the ALBI grade. J Clin Oncol 33:550–558

Pang YY (2000) The Brisbane 2000 terminology of liver anatomy and resections. HPB 2:333–339. (HPB (Oxford) 2002; 4:99–100)

Kawaguchi Y, Fuks D, Kokudo N et al (2018) Difficulty of laparoscopic liver resection: proposal for a new classification. Ann Surg 267:13–17

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA (2004) Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 240:205–213

Slankamenac K, Nederlof N, Pessaux P et al (2014) The comprehensive complication index: a novel and more sensitive endpoint for assessing outcome and reducing sample size in randomized controlled trials. Ann Surg 260:757–762

Rubin DB (1987) Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. Wiley, New York

Harper PR (2005) A review and comparison of classification algorithms for medical decision making. Health Policy 71:315–331

Cescon M, Colecchia A, Cucchetti A et al (2012) Value of transient elastography measured with FibroScan in predicting the outcome of hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg 256:706–712

Cipriani F, Fantini C, Ratti F et al (2018) Laparoscopic liver resections for hepatocellular carcinoma: can we extend the surgical indication in cirrhotic patients? Surg Endosc 32:617–626

Berardi G, Van CS, Fretland AA et al (2017) Evolution of laparoscopic liver surgery from innovation to implementation to mastery: perioperative and oncologic outcomes of 2,238 patients from 4 European Specialized Centers. J Am Coll Surg 225:639–649

Andreatos N, Amini N, Gani F et al (2017) Albumin-bilirubin score: predicting short-term outcomes including bile leak and post-hepatectomy liver failure following hepatic resection. J Gastrointest Surg 21:238–248

Acknowledgements

The authors thank The Italian Group of MILS (I Go MILS) registry and all collaborators who equally contributed to this work.

All Collaborators of the I Go MILS Group listed below are coworkers of the study and contributed to acquisition of data, article review for intellectual content and final approval of the version to be published:

Adelmo Antonucci (Policlinico di Monza, Monza, Italy, e-mail: adelmo.antonucci@policlinicodimonza.it), Francesco Ardito (A. Gemelli, IRCCS, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, Rome, Italy, e-mail: francesco.ardito@unicatt.it), Carlo Battiston (Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale Tumori di Milano, Milan, Italy, e-mail: carlo.battiston@istitutotumori.mi.it), Giulio Belli (SM Loreto Nuovo Hospital, Naples, Italy, e-mail: giubelli@unina.it), Stefano Berti (Ospedale Civile S. Andrea, La Spezia, Italy, e-mail: stefano.berti@asl5.liguria.it), Ugo Boggi (AOU Pisana, Pisa, Italy, e-mail: u.boggi@med.unipi.it), Alberto Brolese (S. Chiara Hospital, Trento, Italy, e-mail: alberto.brolese@apss.tn.it), Fulvio Calise (Pinetagrande hospital, Castel Volturno, Italy, e-mail: fulvio.calise@aocardarelli.it), Graziano Ceccarelli, (San Donato Hospital, Arezzo, Italy, e-mail: graziano.ceccarelli@usl8.toscana.it), Michele Colledan (AO Papa Giovanni XXIII, Bergamo, Italy, e-mail: mcolledan@asst-pg23.it), Andrea Coratti (AOU Careggi, Florence, Italy, e-mail: corattia@aou-careggi.toscana.it), Stefano Di Sandro (ASST Grande Ospedale Metropolitano Niguarda, Milan, Italy, e-mail: stefano.disandro@ospedaleniguarda.it), Ludovica Ferrara (University of Parma, Parma, Italy), Antonio Floridi (AO Ospedale Maggiore, Crema, Italy), Antonio Frena (Central Hospital, Bolzano, Italy, e-mail: antonio.frena@asbz.it), Antonio Giuliani, (AO R. N. Cardarelli, Naples, Italy), Gian Luca Grazi (Istituto Nazionale Tumori Regina Elena, Rome, Italy, e-mail: glgrazi@chirurgiadelfegato.it), Enrico Gringeri (University of Padua, Padova, Italy, e-mail: enrico.gringeri@unipd.it), Guido Griseri (San Paolo Hospital, Savona, Italy, e-mail: g.griseri@asl2.liguria.it), Salvatore Gruttadauria (Mediterranean Institute for Transplantation and Specialization Therapies IRCCS-ISMETT, Palermo, Italy, e-mail: sgruttadauria@ismett.edu), Silvio Guerriero (San Martino Hospital, Belluno, Italy, e-mail: silvio.guerriero@ulss.belluno.it), Elio Jovine (Ospedale Maggiore, Bologna, Italy, e-mail: elio.jovine@ausl.bologna.it), Giovanni Battista Levi Sandri (S. Camillo Hospital, Rome, Italy, e-mail: gblevisandri@gmail.com), Paolo Magistri (University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Italy, e-mail: paolo.magistri@unimore.it), Pietro Maida (Villa Betania Hospital, Napoli, Italy), Pietro Mezzatesta (Casa di Cura La Maddalena, Palermo, Italy, e-mail: mezzatesta@lamaddalenanet.it), Giuseppe Navarra (AOU Policlinico G. Martino, Messina, Italy, e-mail: giuseppe.navarra@polime.it), Amilcare Parisi (AO Santa Maria di Terni, Terni, Italy, e-mail: a.parisi@ospterni.it), Antonio Pinna (Digestive Disease Institute at Cleveland Clinic Abu Dhabi), Francesca Ratti, (IRCCS San Raffaele Hospital, Milan, Italy, e-mail: ratti.francesca@hsr.it), Paolo Reggiani, (IRCCS Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico di Milano, Milan, Italy, e-mail: paolo.reggiani@policlinico.mi.it), Raffaele Romito (Ospedale Maggiore Novara, Italy, e-mail: raffele.romito@maggioreosp.novara.it), Andrea Ruzzenente (University of Verona, Italy, e-mail: andrea.ruzzenente@univr.it), Nadia Russolillo (Mauriziano Umberto I Hospital, Torino, Italy, e-mail: nadia.russolillo@libero.it), Roberto Santambrogio (AO San Paolo, Milan, Italy, e-mail: roberto.santambrogio@asst-santipaolocarlo.it), Giovanni Sgroi (AO Treviglio-Caravaggio, Treviglio, Italy, e-mail: giovanni_sgroi@asst-bgovest.it), Abdallah Slim (AO Desio e Vimercate, Vimercate, Italy, e-mail: abdallah.slim@aovimercate.org), Guido Torzilli (Istituto Clinico Humanitas, Rozzano, Italy, e-mail: guido.torzilli@hunimed.eu), Leonardo Vincenti (AOU Consorziale Policlinico, Bari, Italy), Fausto Zamboni (Brotzu Hospital, Cagliari, Italy, e-mail: faustozamboni@yahoo.it).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

Carlo Sposito, Michela Monteleone, Luca Aldrighetti, Umberto Cillo, Raffaele Dalla Valle, Alfredo Guglielmi, Giuseppe Maria Ettorre, Alessandro Ferrero, Fabrizio Di Benedetto, Giorgio Ettore Rossi, Luciano De Carlis, Felice Giuliante, and Vincenzo Mazzaferro have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sposito, C., Monteleone, M., Aldrighetti, L. et al. Preoperative predictors of liver decompensation after mini-invasive liver resection. Surg Endosc 35, 718–727 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-020-07438-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-020-07438-2