Abstract

Background

Obesity has been reported to adversely affect the outcome of laparoscopic antireflux surgery (LARS). This study examined pre- and postoperative clinical and objective outcomes and quality of life in obese and normal-weight patients following LARS at a specialized centre.

Methods

Prospective data from patients subjected to LARS (Nissen or Toupet fundoplication) for symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease in the General Public Hospital of Zell am See were analyzed. Patients were divided in two groups: normal weight [body mass index (BMI) 20–25 kg/m2] and obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2). Gastrointestinal quality of life index (GIQLI), symptom grading, esophageal manometry and multichannel intraluminal impedance monitoring data were documented and compared preoperatively and at 1 year postoperatively.

Result

The study cohort included forty normal-weight and forty obese patients. Mean follow-up was 14.7 ± 2.4 months. The mean GIQLI improved significantly after surgery in both groups (p < 0.001, for both). Clinical outcomes improved following surgery regardless of BMI. There were significant improvements of typical and atypical reflux symptoms in normal weight and obese (p = 0.007; p = 0.006, respectively), but no difference in gas bloat and bowel dysfunction symptoms could be found. No intra- or perioperative complications occurred. A total of six patients had to be reoperated (7.5 %), two (5 %) in the obese group and four (10 %) in the normal-weight group, because of recurrent hiatal hernia and slipping of the wrap or persistent dysphagia due to closure of the wrap.

Conclusion

Obesity is not associated with a poorer clinical and objective outcome after LARS. Increased BMI seems not to be a risk factor for recurrent symptomatology and reoperation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Overweight, defined according to the World Health Organization’s classification, as a body mass index (BMI) of ≥25 kg/m2 [1] is associated with an increased risk for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms, erosive esophagitis, and esophageal adenocarcinoma [2, 3]. Obesity is associated with higher intra-abdominal pressures, impaired gastric emptying [4], decreased lower esophageal sphincter pressure, and increased frequency of transient sphincter relaxation and presence of hiatal hernia, thus leading to increased esophageal acid exposure, which has a role in initiating and promoting GERD [5]. Laparoscopic antireflux surgery (LARS) has become a widely accepted surgical approach for the treatment of GERD; however, study data on safety and efficacy of LARS in obese patients are not yet well established and results have been controversial. Several authors reported difference in surgical outcome between normal-weight patients and obese undergoing LARS, leading to an increased risk of postoperative hiatal hernia, need for revisional operation, intraoperative complications, and recurrent reflux symptoms [6–9]. In contrast to these studies, others demonstrate that obesity does not adversely affect the outcome of LARS [10–16]. Importantly, bariatric procedures, primarily designed for weight reduction, such as the Roux-en-Y bypass (RYGB), have been shown to improve reflux symptoms; therefore, some authors have advocated RYGB as an initial operation for obese patients with GERD [17, 18]. The aim of this study was to examine subjective and objective clinical outcomes of LARS in patients with body a mass index (BMI) ≥30 kg/m2 compared to normal-weight patients with a BMI 20–25 kg/m2 performed in a single institution by only two surgeons.

Patients and methods

Retrospective analysis of eighty consecutive patients with diagnosed GERD who underwent LARS (Nissen or Toupet fundoplication) in the General Public Hospital of Zell am See were entered prospectively into a computerized database between November 2007 and September 2011. All patients underwent preoperative assessment with gastrointestinal endoscopy, a barium esophagogastric study, esophageal manometry and 24-h ambulatory multichannel intraluminal impedance (MII). Indication for surgery in all patients was duration of GERD symptoms of at least 1 year, persistent or recurrent symptoms despite optimal treatment with a proton pump inhibitor for at least 6 months, persistent or recurrent complications of GERD, reduced quality of life, and pathological values in the preoperative evaluated functional parameters (MII and manometry). None of the patients had previously been subjected to an antireflux procedure. Inclusion criteria for the study were the availability of preoperative demographic data: preoperative height and weight data evaluation for calculation of BMI. Exclusion criteria were refundoplication, paraesophageal hiatus hernia, and an American Society of Anesthesiologists of III or greater. The study group was initially divided into two groups based on their BMI according to the World Health Organization classification of overweight and obesity: normal-weight BMI <25 and obese BMI ≥30. Pre- and post-operative data between normal-weight and obese patients were compared.

Surgical technique

All the patients underwent laparoscopic fundoplication in a standardized manner by two experienced laparoscopic surgeons. Between October 2007 and October 2010 patients were randomly assigned to undergo either laparoscopic 360° “floppy” Nissen fundoplication (LNF) or laparoscopic 270° Toupet fundoplication (LTF). From October 2010 all patients received Toupet fundoplication due to the results of an internal audit and prospective randomized trial [21]. Our technique of laparoscopic fundoplication has been described previously in detail [22]. The operation technique was standardized.

Symptom evaluation

Symptom grading was carried out on in a standardized manner on all patients preoperatively and 12 months postoperatively using a written questionnaire, which has been described previously in detail [21]. The severity and intensity of 14 symptoms were evaluated in a 4-point scale for specific and non-specific symptoms of GERD, including heartburn, dysphagia, regurgitation, chest and epigastric pain, cough, hoarseness, asthma, epigastric fullness, flatulence, diarrhea, constipation, ability to belch, bloatedness, and distortion of taste. Additionally, four different scores were extracted to assess symptoms specific for reflux (heartburn, regurgitation, chest pain), gas-bloat (fullness, bloatedness), bowel-dysfunction (diarrhea, constipation, flatulence) and atypical reflux symptoms (cough, hoarseness, asthma, distortion of taste).

Quality of life evaluation

Quality of life was evaluated by means of the German gastrointestinal quality of life index (GIQLI) [21]. This questionnaire has been validated and recommended by the European Study Group for Antireflux Surgery [22]. Including 36 items, the general response to the GIQLI is graded from 0 to 144 points. The GIQLI is divided into 5 subdimensions: gastrointestinal symptoms (0–76 points), emotional status (0–20 points), physical functions (0–28 points), social functions (0–16 points), and a single item for stress of medical treatment (0–4 points). A healthy patient has an approximate grad of 122,6 points. Higher scores indicate higher quality of life.

Follow-up evaluation

GIQLI, symptom grading esophageal manometry and monitoring MII data were completed preoperatively and 1 year after surgery. After surgery, patients were controlled following the same preoperative protocol evaluating symptoms, endoscopic and esophageal functional tests, in order to determine the clinical and objective results. Postoperative barium esophagogastric study was not preformed routinely during follow-up period. The follow-up assessment was standardized.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS statistical analysis software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). All data were tested for normal distribution by the Kolmogorow-Smirnow test. Paired values were compared using the t test. Outcomes between obese and normal-weight patients were compared using Mann–Whitney U test and comparisons between preoperative and follow-up data were performed with Wilcoxon matched pair test. Statistical significance was set at a p value <0.05. Data are presented as mean values ± SD, unless otherwise indicated.

Results

Preoperative results

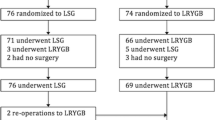

Eighty patients could be identified, forty normal-weight (BMI 20–25 kg/m2) and forty obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2). Thirty-five (44 %) of these patients were women and 45 (56 %) were men. The mean BMI was 23.61 kg/m2 [20–25] in the normal-weight group and 32.28 kg/m2 (30–42) in the obese group. Patients’ demographic and preoperative subjective and objective clinical data are shown in Table 1.

Postoperative results

Fifty-eight patients underwent Toupet fundoplication (31 in normal-weight group and 27 in the obese group), with the remainder undergoing Nissen fundoplication (12 in normal-weight group and 10 in obese). The choice of fundoplication type was not influenced by BMI. In the follow-up period of 12 months, six patients in the normal-weight group and four in the obese group were lost to follow-up, either because they moved to other regions or were unwilling to attend further clinical visits. The mean follow-up time was 14.7 ± 2.4 months. There were no intraoperative or perioperative complications and all procedures could be completed laparoscopically. Six patients (7.5 %) required reoperation prior to the twelve-month follow-up period. They were admitted to our hospital with present clinical symptoms (i.e., pain, dysphagia) and underwent again the preoperative assessment procedures with gastrointestinal endoscopy, a barium esophagogastric study, esophageal manometry and 24-h ambulatory MII. The diagnosis for reoperation was based on patients’ symptoms and not just because of a pathologic radiological finding. Two re-operations (5 %) had to be performed within the obese group. One was for troublesome dysphagia caused by a tight closer of the wrap, while the other was because of recurrent hiatal hernia with symptomatic slipping of the wrap. Four (10 %) postoperative complications occurred in the normal-weight group, two due to the slipping of the wrap and two because of dysphagia. Postoperative complications and the requirement for later surgical revision were not influenced by the preoperative weight. All patients re-operated received a Toupet fundoplication. No operation-related death or other complications occurred during follow-up period. There were no significant differences between groups in the presence of subjective data (quality of life, typical and atypical reflux symptoms) and measured objective data (esophageal manometry and MII data). Overall, patients with higher BMI had a similar clinical outcome to normal-weight patients. Both groups showed significant reduction in heartburn scores, dysphagia, and overall satisfaction. The pre- and postoperative LES resting pressures were measured and they normalized postoperatively in both groups. When both groups were compared postoperatively there was no significant difference in any measured parameter. Table 2 summarizes comparisons between normal-weight and obese patients’ postoperative outcome data.

Discussion

Excessive body weight is a significant independent risk factor for hiatal hernia and is associated with GERD [2, 3]. Since the early 1990, the status of LARS has moved from experimental to routine, with conflict findings reported in recent literature describing correlations between obesity and surgical outcome in patients undergoing LARS [6–16] as shown in Table 3.

Worse results after fundoplication in obese patients were associated with increased risk of recurrent reflux, postoperative paraesophageal hiatus herniation, and intraoperative difficulties [6–9]. In this study, a BMI over 30 was not significantly associated with a poorer outcome after LARS. Reflux symptoms scores were significantly improved in obese and non-obese patients after surgery. According to previous findings, in our study, obesity was associated with a decreased lower esophageal sphincter pressure compared to normal-weight patients, thus leading to increased esophageal acid exposure [5]. Conversion rate because of difficulties with exposure, bleeding or adhesions varies in the literature from 2 to 10 % [23, 24]. We experienced no intraoperative complications and the conversion rate was zero, which demonstrates that patients had undergone surgery by well-experienced surgeons. The evidence that obese patients who have GERD are at risk for failure of antireflux procedures is also suggestive but not conclusive. Most of the available studies have had low patient numbers, short follow-up period and subsequent low statistical power, or have examined patient populations that are not selective of the bariatric population (e.g., BMI <35 kg/m2). In a retrospective study of 505 patients, where 76 patients were obese (BMI >30) Winslow et al. found that symptom relief and complication rates were likely across all BMI categories [10]. Similar, Fraser et al. studied the postoperative outcome after LARS in 194 patients, only 14 were obese (BMI >30), they did not report a poorer outcome in obese patients following LARS [15]. In a multivariate analysis performed by Campos et al. on 199 patients there was also no trend for a poorer outcome in morbidly obese patients following LNF for GERD symptoms [16]. Anvari et al. preformed a prospective analysis evaluating objective outcome parameters such as increased lower esophageal sphincter pressure, less acidification of the esophagus as shown by pre- and post-operative manometry and pH-metry, with a mean follow-up of 41.5 months on data from 70 Nissen operations in patients with BMI >30 compared to 70 consecutive Nissen procedures in patients with BMI <30. High BMI was not associated with significantly increased risk or recurrence rate, although the slightly increased number of trocars needed, operating time, and delay in discharge for obese subjects pointed out both the feasibility but also the more demanding nature of the operation in obese subjects. Obesity was not associated with an adverse effect on the outcome after laparoscopic Nissen funduplication [13]. In accordance to this published series, where patients with normal and high BMI were included [10, 13–15], in the present study reflux symptoms scores were significantly improved in obese and normal-weight patients after surgery. In several studies reflux symptom control in obese patients was treated with laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding [25, 26], partly because of some of the reports that claimed that the outcome of antireflux surgery is worse in the obese. Surgical management for obesity with bariatric procedures, especially Roux-en-Y gastric bypass has been reported to be an effective long-term control of reflux symptoms, with the additional benefit of weight loss [18, 27, 28]. Compared to LARS, negative physiological effects after RYGB, like the absorption of Vitamin B12, Vitamin D, calcium, and iron can be greatly affected because of the proximal duodenum bypass, and most patients need to take oral supplementation [29]. However, the results of this surgical management appear to be less reliable. Klaus et al. treated 164 patients with symptomatic reflux with laparoscopic gastric banding surgery. After a mean follow-up of 33 months, 52 (31.7 %) of the patients reported persistent or aggravated reflux symptoms, a result that is inferior to the reported symptom control with LARS [30]. Eligible candidates for bariatric surgery are patients with a BMI >40 kg/m2 and very few of these patients are without comorbidities, including GERD. Our data support LARS as a treatment for gastro-esophageal reflux in obese patients with a BMI <35 kg/m2 and the outcome is likely to be similar to that of patients who are in the normal-weight range at the time of surgery. We cannot state that LARS is an effective treatment for morbidly obese patients (BMI >35 kg/m2), because in our study we evaluated patients with a mean BMI of 32.28 kg/m2. All other studies addressing the same issue have demonstrated that LARS as the treatment of choice for GERD in obese patient can be safely and successfully performed [10–16]. Tekin et al. reviewed 1,000 patients who underwent LARS with a mean follow-up of 53.33 months, 132 patients were obese (BMI >30). There was no increase in complications with increase in obesity, in accordance with our results. Heartburn and regurgitation symptoms were improved significantly after surgery [8]. Hahnloser et al. reported that patients with a higher BMI experienced intraoperative or postoperative complications significantly more often than patients with normal BMI [7]. Another study that reported a significantly increased recurrence of reflux after LARS in obese patients was also retrospective, including 48 obese patients (BMI <30) out of 224 observed [6]. Only these two studies [6, 7] reported higher recurrence rates in obese patients after LARS. Nevertheless, our findings do not support that. In our study, postoperative complications occurred mainly in normal-weight patients, dysphagia being the most frequent complication in both groups, a complication that is difficult to predict [24]. The association of BMI, GERD and surgical outcome, is very important for determination of the adequate treatment for each patient. However, our study has some shortcomings. One could argue for a statistical type II error and short follow-up of 1 year. The loss of follow-up makes selection bias possible. The twelve-months recall period used may have resulted in recall bias. Strengths of our study are that the data were collected from a prospective database of randomized controlled trials and that preoperative data were available for all patients without any dropouts. We included objective measure of reflux control such as pH monitoring and Quality of Life symptom evaluation pre- and postoperatively. The combination of clinical and objective outcome measures is a reliable and valid tool for reflux symptom severity assessment and treatment response sufficiency than data from pH monitoring and endoscopy alone.

Conclusion

LARS provides a significant improvement of objective and subjective parameters of GERD in a cohort of obese and normal-weight patients. A BMI ≤35 should not be considered a contraindication for LARS; good outcomes can be expected if the procedure is performed by an experienced surgeon. Obesity does not affect the success of antireflux surgery.

References

WHO Expert Committee (2000) Obesity:preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organization Tech Rep Ser 894(I–xiii):1–253

Corley DA, Kubo A (2006) Body mass index and gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 101(11):2619–2628

Hampel H, Abraham NS, El-Serag HB (2005) Meta-analysis: obesity and the risk for gastroesophageal reflux disease and its complications. Ann Intern Med 143(3):199–211

Barak N, Ehrenpreis ED, Harrison JR, Sitrin MD (2002) Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in obesity: pathophysiological and therapeutic considerations. Obes Rev 3(1):9–15

Orlando RC (2001) Overview of the mechanisms of gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Med 3(111 Suppl 8A):174S–177S

Perez AR, Moncure AC, Rattner DW (2001) Obesity adversely affects the outcome of antireflux operations. Surg Endosc 15(9):986–989

Hahnloser D, Schumacher M, Cavin R, Cosendey B, Petropoulos P (2002) Risk factors for complications of laparoscopic nissen fundoplication. Surg Endosc 16(1):43–47

Tekin K, Toydemir T, Yerdel MA (2012) Is laparoscopic antireflux surgery safe and effective in obese patients? Surg Endosc 26(1):86–95

Morgenthal CB, Lin E, Shane MD, Hunter JG, Smith CD (2007) Who will fail laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication? Preoperative prediction of long-term outcomes. Surg Endosc 21(11):1978–1984

Winslow ER, Frisella MM, Soper NJ, Klingensmith ME (2003) Obesity does not adversely affect the outcome of laparoscopic antireflux surgery (LARS). Surg Endosc 17(12):2003–2011

Ng VV, Booth MI, Stratford JJ, Jones L, Sohanpal J, Dehn TC (2007) Laparoscopic anti-reflux surgery is effective in obese patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 89(7):696–702

D’Alessio MJ, Arnaoutakis D, Giarelli N, Villadolid DV, Rosemurgy AS (2005) Obesity is not a contraindication to laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. J Gastrointest Surg 9(7):949–954

Anvari M, Bamehriz F (2006) Outcome of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication in patients with body mass index > or = 35. Surg Endosc 20(2):230–234

Chisholm JA, Jamieson GG, Lally CJ, Devitt PG, Game PA, Watson DI (2009) The effect of obesity on the outcome of laparoscopic antireflux surgery. J Gastrointest Surg 13(6):1064–1070

Fraser J, Watson DI, O’Boyle CJ, Jamieson GG (2001) Obesity and its effect on outcome of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. Dis Esophagus 14(1):50–53

Campos GM, Peters JH, DeMeester TR, Oberg S, Crookes PF, Tan S et al (1999) Multivariate analysis of factors predicting outcome after laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. J Gastrointest Surg 3(3):292–300

Varela JE, Hinojosa MW, Nguyen NT (2009) Laparoscopic fundoplication compared with laparoscopic gastric bypass in morbidly obese patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Surg Obes Relat Dis 5(2):139–143

Frezza EE, Ikramuddin S, Gourash W, Rakitt T, Kingston A, Luketich J et al (2002) Symptomatic improvement in gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) following laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Endosc 16(7):1027–1031

Eypasch E, Williams JI, Wood-Dauphinee S, Ure BM, Schmulling C, Neugebauer E et al (1995) Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index: development, validation and application of a new instrument. Br J Surg 82(2):216–222

Eypasch E, Wood-Dauphinee S, Williams JI, Ure B, Neugebauer E, Troidl H (1993) The Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index. A clinical index for measuring patient status in gastroenterologic surgery. Chirurg 64(4):264–274

Koch OO, Kaindlstorfer A, Antoniou SA, Luketina RR, Emmanuel K, Pointner R (2013) Comparison of results from a randomized trial 1 year after laparoscopic Nissen and Toupet fundoplications. Surg Endosc 27(7):2383–2390

Bammer T, Pointner R, Hinder R (2000) Standard technique for laparoscopic Nissen and Toupet fundoplication. Eur Surg 32:3–6

Champault GG, Barrat C, Rozon RC, Rizk N, Catheline JM (1999) The effect of the learning curve on the outcome of laparoscopic treatment for gastroesophageal reflux. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 9(6):375–381

Zaninotto G, Molena D, Ancona E (2000) A prospective multicenter study on laparoscopic treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease in Italy: type of surgery, conversions, complications, and early results. Study Group for the Laparoscopic Treatment of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease of the Italian Society of Endoscopic Surgery (SICE). Surg Endosc 14(3):282–288

Iovino P, Angrisani L, Tremolaterra F, Nirchio E, Ciannella M, Borrelli V et al (2002) Abnormal esophageal acid exposure is common in morbidly obese patients and improves after a successful Lap-band system implantation. Surg Endosc 16(11):1631–1635

Dixon JB, O’Brien PE (1999) Gastroesophageal reflux in obesity: the effect of lap-band placement. Obes Surg 9(6):527–531

Nelson LG, Gonzalez R, Haines K, Gallagher SF, Murr MM (2005) Amelioration of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for clinically significant obesity. Am Surg 71(11):950–953 discussion 953-4

Braghetto I, Korn O, Csendes A, Gutierrez L, Valladares H, Chacon M (2012) Laparoscopic treatment of obese patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease and Barrett’s esophagus: a prospective study. Obes Surg 22(5):764–772

Smith CD, Herkes SB, Behrns KE, Fairbanks VF, Kelly KA, Sarr MG (1993) Gastric acid secretion and vitamin B12 absorption after vertical Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Ann Surg 218(1):91–96

Klaus A, Gruber I, Wetscher G, Nehoda H, Aigner F, Peer R et al (2006) Prevalent esophageal body motility disorders underlie aggravation of GERD symptoms in morbidly obese patients following adjustable gastric banding. Arch Surg 141(3):247–251

Disclosures

Ruzica- Rosalia Luketina, Oliver Owen Koch, Gernot Köhler, Stavros A. Antoniou, Klaus Emmanuel, and Rudolph Pointner have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Luketina, RR., Koch, O.O., Köhler, G. et al. Obesity does not affect the outcome of laparoscopic antireflux surgery. Surg Endosc 29, 1327–1333 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-014-3842-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-014-3842-x