Abstract

Cryptosporidium is an important intestinal zoonotic pathogen that can infect various hosts and cause diarrheal disease. There are no reports on the prevalence and molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium in wild birds in Cyprus. Therefore, the present study aimed to determine the prevalence of Cryptosporidium spp. and genotypes in wild birds found at Phassouri Reedbeds (Akrotiri Wetlands), Cyprus. Fecal samples of 75 wild birds (Eurasian coot Fulica atra, N = 48; Eurasian teal Anas crecca, N = 20; duck – Anas spp., Ν = 7) were screened for Cryptosporidium by PCR amplification and sequencing. Only one sample (1.3%) belonging to a Eurasian coot was PCR-positive for Cryptosporidium. Based on sequencing of the 18S rRNA locus, this species was identified as Cryptosporidium proventriculi. This is the first report on the molecular identification of this Cryptosporidium species in a Eurasian coot.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cryptosporidium is an important zoonotic enteric protozoan parasite that infects many hosts through the fecal–oral route, including humans and domestic and wild animals worldwide (Ryan et al. 2014, 2016). It is one of the leading causes of diarrhea worldwide, second only to rotavirus (Ryan and Hijjawi 2015; Ryan et al. 2016; Liu et al. 2016) and a significant cause of child mortality worldwide (Kotloff 2017; Karanis 2018).

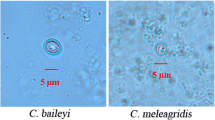

Various studies have identified the occurrence of Cryptosporidium species in wild waterbirds in different countries and used molecular tools to determine the species (Jian et al. 2021). Cryptosporidium parvum was found in white storks (Ciconia ciconia), mute swans (Cygnus olor), common mergansers (Mergus merganser) (Majewska et al. 2009), mallards (Anas platyrhynchos) (Kuhn et al. 2002) and Canada geese (Branta canadensis) (Zhou et al. 2004), Cryptosporidium duck genotype in Canada geese (Zhou et al. 2004), Cryptosporidium baileyi in mallards (Wang et al. 2010), black-headed gulls (Chroicocephalus ridibundus) (Pavlásek 1993), and ruddy shelducks (Tadorna ferruginea) (Amer et al. 2010), Cryptosporidium goose genotypes I and II in Canada geese (Zhou et al. 2004), and Cryptosporidium avian genotype III in black-headed and brown-headed gulls (Chroicocephalus brunnicephalus) (Koompapong et al. 2014) and waterbirds (Cano et al. 2016). Interestingly, the prevalence of Cryptosporidium varies significantly among these studies, ranging from 0.5 to 77%, depending on the country and the bird species.

There is evidence that cryptosporidiosis can have a significant clinical impact on birds. For example, infection of domestic birds can lead to extensive economic losses for the poultry industry (Majewska et al. 2009; Batz et al. 2012, Holubova et al. 2018). The present study aimed to determine the prevalence and molecular identification of Cryptosporidium species in wild birds for the first time in Cyprus.

Materials and methods

Study area

Phassouri Reedbeds (also known as Akrotiri Marsh) is a unique, natural, freshwater wetland in Cyprus, covering an area of 150 ha (1.5 km2). It is part of the Akrotiri Wetland complex, the largest natural wetland complex of the island, covering roughly 25 km2 and located at Akrotiri Peninsula (Zogaris 2017). A seasonal salt-lake occupies the center of the Peninsula and is part of a wider aquatic system with a number of saline and freshwater habitats. Phassouri Reedbeds lies within the Cyprus Sovereign Base Area and is also a state land. It is part of a Ramsar site (Salathé 2002) and a designated Special Protection Area (SPA), equivalent to the EU designation (Zogaris 2017). Dominated by a large Phragmites australis reedbed and surrounding wet meadows, it is crossed by a system of canals and ditches and has a variable flooding regime with respect to artificial and human modified flooding. The connection between the reedbeds and humans dates back centuries as, among other things, the area is still used for cattle grazing by the residents of nearby Akrotiri village (Zogaris 2017).

As part of the Akrotiri Wetland complex, Phassouri Reedbeds constitutes a congregation site for waterbirds, including globally important numbers of certain species and a raptor bottleneck site in autumn, with globally important congregations of four birds of prey. Notable migrants occur in numbers of regional importance, as well as important breeding birds. Phassouri Reedbeds is amongst the best breeding sites in Cyprus for the Ferruginous Duck Aythya nyroca (Hellicar et al., 2014) and the only site in Cyprus for certain rare and threatened flora species (Tsintides et al. 2007).

Sample collection

Seventy-five individual wild bird fecal samples (48 Eurasian coot, Fulica atra, 20 Eurasian teal, Anas crecca and 7 Duck, Anas spp.) were collected from the ground at Phassouri Reedbeds, Akrotiri Wetlands (Cyprus) on 25 February 2021.

Upon observing groups of birds, the observers walked toward them and collected the feces. Each fresh fecal sample was placed in a sterile polystyrene tube (50-ml centrifuge tube) with records of the bird species/group, date, location, and identification number. The samples were transferred to the laboratory on the same day and were stored at 4 °C until DNA extraction within 3 weeks after collection.

DNA extraction and PCR

The total genomic DNA was extracted from each fecal sample with a QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cryptosporidium species were determined by nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of an 18S rRNA locus fragment (600 bp) using previously described primers (Silva et al., 2013). The primers used for the first amplification were SHP1 (forward) 5′ ACC TAT CAG CTT TAG ACG GTA GGG TAT 3′ and SHP2 (reverse) 5′ TTC TCA TAA GGT GCT GAA GGA GTA AGG 3′. The primers used for the second amplification were SHP3 (forward) 5′ ACA GGG AGG TAG TGA CAA GAA ATA ACA 3′ and SSU-R3 (reverse) 5′ AAG GAG TAA GGA ACA ACC TCC A 3′. Cycling conditions used in both amplifications were 94 °C for 3 min, 35 cycles of 94 °C for 45 s, 56 °C for 45 s, and 72 °C for 60 s, followed by a final extension of 72 °C for 7 min.

Sequencing and phylogenetic analysis

The DNA band of the positive PCR product was gel extracted and purified using the Blirt ExtractMe DNA Kit (Blirt, Gdansk, Poland). The purified PCR product was sent for sequencing (using the forward primer of the nested PCR reaction) to Macrogen Ltd., Europe, Amsterdam. For the determination of Cryptosporidium species, the sequence was subjected to BLAST (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast) searches at NCBI GenBank. The sequence was deposited in the NCBI GenBank under the accession number: OM870407. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the maximum likelihood method in MEGA 11 software, with Bootstrap 1000 replicates. Evolutionary distances were calculated using the Kimura two-parameter model (https://www.megasoftware.net/).

Results

Only one sample (1.3%) was PCR-positive for Cryptosporidium and was further identified by DNA sequencing and Blastn analysis as Cryptosporidium proventriculi. This sample belonged to a Eurasian coot (1/48 positive samples). No positive sample was detected in Eurasian teals (0/20) and ducks (0/7).

The phylogenetic analysis using the Mega11 software indicated that the 18S rRNA sequence of the Cryptosporidium proventriculi isolated in this study formed a well-defined cluster with the respective reference sequences (Fig. 1).

Discussion

The present study identified Cryptosporidium species in wild birds in Cyprus and is the first report of Cryptosporidium proventriculi in the Eurasian coot. Previously, Cryptosporidium avian genotype III was described as a new species C. proventriculi sp.n. based on morphological, molecular, and biological data (Holubová et al. 2019). To date, C. proventriculi has been reported from birds in the orders Psittaciformes, Passeriformes, Piciformes, and Anseriformes (Holubová et al. 2019). This is the first report of this species in the order Gruiformes. Cryptosporidiosis in birds manifests in various clinical forms depending on the species of Cryptosporidium and the site of infection (Nakamura and Meireles, 2015). However, knowledge of the course of infection and disease presentation in birds is limited. Both Ng et al. (2006) and Holubová et al. (2019) found that C. proventriculi did not cause clinical disease or mortality in naturally or experimentally infected birds. In the present study, C. proventriculi was only identified in one fecal sample, and therefore, it is not possible to determine the clinical impact on the host.

Cryptosporidium proventriculi is the second Cryptosporidium species identified in Eurasian coot, with C. parvum previously identified in two out of four fecal samples collected at Lake Balaton, Hungary (Plutzer and Tomor 2009). Cryptosporidium proventriculi was also found in 15.4% of black-and brown-headed gull fecal samples collected at Bang Poo Nature Reserve, Thailand (Koompapong et al. 2014) and 2.3% of waterbird fecal samples, not identified to the species level, collected at Salburua Wetlands, Spain (Cano et al. 2016), demonstrating the wide geographic presence of Cryptosporidium proventriculi in wild birds.

Data on the epidemiology of Cryptosporidium in Cyprus is limited. To our knowledge, only two studies to date have indicated a high occurrence of Cryptosporidium in domestic animals. In the first study, Schou et al. (2022) reported a high prevalence of Cryptosporidium in domestic sheep (50%) and goats (30%). The species identified were C. xiaoi and C. ubiquitum in sheep and C. parvum in goats. In the second study, Hoque et al. (2022) found that 40% of domestic cattle were positive for Cryptosporidium. The species identified were C. bovis, C. ryanae, and C. parvum. Interestingly, the occurrence of Cryptosporidium in wild birds is low (1.3%) compared to domestic animals, probably because it is easier for the infected animals to spread the parasite on farms. Moreover, this is the first time that C. proventriculi has been reported in Cyprus.

Wild birds around Phassouri Reedbeds are primarily migratory, and the area is a critical stop-over site on an important migratory bird flyway. The surrounding areas of Phassouri Reedbeds support cattle and horse grazing, and the water sources are shared with wild animals. Cryptosporidium parasites may be transmitted during bird migration. However, most human infections are caused by C. hominis and C. parvum (Ryan et al. 2016). Therefore, the contribution of wild birds in the transmission of cryptosporidiosis in Cyprus through the fecal–oral route and through the contamination of water sources is unclear. Molecular surveillance studies are necessary to provide reliable information for health care and policymakers so that more funds will be available for research, diagnosis, and treatment of cryptosporidiosis and the prevention of possible Cryptosporidium outbreaks.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first report of Cryptosporidium in wild birds in Cyprus and of Cryptosporidium proventriculi in Eurasian coot. The results of this study indicate that there is a low prevalence of Cryptosporidium in wild birds compared to domestic animals in Cyprus. Further studies with more samples are needed to explore further research outcomes.

Data availability

The material obtained in this study is stored at the Laboratory of Health Sciences Faculty of the Nicosia University. Representative nucleotide sequences obtained in this study were submitted to the GenBank® under the accession number: OM870407.

References

Amer S, Wang C, He H (2010) First detection of Cryptosporidium baileyi in ruddy shelduck (Tadorna ferruginea) in China. J Vet Med Sci 72:935–938. https://doi.org/10.1292/jvms.09-0515

Batz MB, Hoffmann S, Morris JG (2012) Ranking the disease burden of 14 pathogens in food sources in the United States using attribution data from outbreak investigations and expert elicitation. J Food Prot 75:1278–1291. https://doi.org/10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-11-418

Cano L, de Lucio A, Bailo B, Cardona G A, Muadica ASO, Lobo L, Carmena D. (2016). Identification and genotyping of Giardia spp. and Cryptosporidium spp. isolates in aquatic birds in the Salburua wetlands, Álava, Northern Spain. Vet Parasitol 221:144-8 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2016.03.026

Hellicar MA, Anastasi V, Beton D Snape R (2014). Important bird areas of Cyprus. Bird Life Cyprus, Nicosia, Cyprus

Holubová N, Sak B, Hlásková L, Květoňová D, Hanzal V, Rajský D, Rost M, McEvoy J, Kváč M (2018) Host specificity and age-dependent resistance to Cryptosporidium avium infection in chickens, ducks and pheasants. Exp Parasit 191:62–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exppara.2018.06.007

Holubová N, Zikmundová V, Limpouchová Z, Sak B, Konečný R, Hlásková L, Rajský D, Kopacz Z, McEvoy J, Kváč M (2019) Cryptosporidium proventriculi sp. n. (Apicomplexa: Cryptosporidiidae) in Psittaciformes birds. Europ J Protistol 69:70–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejop.2019.03.001

Hoque S, Mavrides DE, Pinto P, Costa S, Begum N, Azevedo-Ribeiro C, Liapi M, Kváč M, Malas S, Gentekaki E, Tsaousis AD (2022) High occurrence of zoonotic subtypes of Cryptosporidium parvum in Cypriot dairy farms. Microorg 10:531

Jian Y, Zhang X, Li X, Schou C, Charalambidou I, Ma L, Karanis P (2021) Occurrence of Cryptosporidium and Giardia in wild birds from Qinghai Lake on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, China. Parasitol Res 120: 615-628.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-020-06993-w

Karanis P (2018) The truth about in vitro culture of Cryptosporidium species. Parasitol 145:855–864. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182017001937

Koompapong K, Mori H, Thammasonthijarern N, PrasertbunR, Pintong A R, PoprukS, RojekittikhunW, Chaisiri K, Sukthana Y, Mahittikorn A (2014) Molecular identification of Cryptosporidium spp. in seagulls, pigeons, dogs, and cats in Thailand. Paras 21: 52. https://doi.org/10.1051/parasite/2014053

Kotloff KL (2017) The burden and etiology of diarrheal illness in developing countries. Ped Clinics North America 64:799–814. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2017.03.006

Kuhn RC, Rock CM, Oshima KH (2002) Occurrence of Cryptosporidium and Giardia in wild ducks along the Rio Grande River valley in Southern New Mexico. Appl Environ Microbiol 68:161–165. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.68.1.161-165.2002

Liu J, Platts-Mills JA, Juma J, Kabir F, Nkeze J, Okoi C, Operario DJ, Uddin J, Ahmed S, Alonso PL, Antonio M, Becker SM, Blackwelder WC, Breiman RF, FaruqueAS G, Fields B, Gratz J, Haque R, Hossain A, … Houpt ER (2016) Use of quantitative molecular diagnostic methods to identify causes of diarrhoea in children: a reanalysis of the GEMS case-control study. Lancet 388: 1291-1301.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31529-X

Majewska AC, Graczyk TK, Słodkowicz-KowalskaA TL, Jędrzejewski S, Zduniak P, Solarczyk P, Nowosad A, Nowosad P (2009) The role of free-ranging, captive, and domestic birds of Western Poland in environmental contamination with Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts and Giardia lamblia cysts. Parasitol Res 104:1093–1099. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-008-1293-9

Nakamura AA, Meireles MV (2015) Cryptosporidium infections in birds - a review. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 24:253–267. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612015063

Ng J, Pavlasek I, Ryan U (2006) Identification of novel Cryptosporidium genotypes from avian hosts. App Environ Microbiol 72:7548–7553. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01352-06

Pavlásek I (1993) The black-headed gull (Larus ridibundus L.), a new host for Cryptosporidium baileyi (Apicomplexa: Cryptosporidiidae). Veterinární Medicína 38:629–638

Plutzer J, Tomor B (2009) The role of aquatic birds in the environmental dissemination of human pathogenic Giardia duodenalis cysts and Cryptosporidium oocysts in Hungary. Parasitol Internat 58:227–231

Ryan U, Hijjawi N (2015) New developments in Cryptosporidium research. Int J Parasitol 45:367–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpara.2015.01.009

Ryan U, Zahedi A, PapariniA, (2016) Cryptosporidium in humans and animals—a one health approach to prophylaxis. Paras Immunol 38:535–547. https://doi.org/10.1111/pim.12350

Ryan U, Fayer R, Xiao L (2014) Cryptosporidium species in humans and animals: current understanding and research needs. Parasitol 141: 1667–1685

Salathé T (2002) Ramsar mission to Cyprus’ Akrotiri salt lake. Akrotiri Wetland Complex, UK Sovereign Base Area, Cyprus. Unpublished Mission Report, 17–21 June 2002.

Schou C, Hasapis KA, Karanis P (2022) Molecular identification of Cryptosporidium species from domestic ruminants and wild reptiles in Cyprus. Parasitol Res 121:2193–2198

Tsintides T, Christodoulou CS, Delipetrou P, Georgiou K (eds) (2007) The red data book of the flora of Cyprus. Cyprus Forestry Association, Nicosia, Cyprus.

Wang R, Jian F, Sun Y, Hu Q, Zhu J, Wang F, Ning C, Zhang L, Xiao L (2010) Large-scale survey of Cryptosporidium spp. in chickens and Pekin ducks (Anas platyrhynchos) in Henan, China: prevalence and molecular characterization. Avian Pathol 39:447–451

Zhou L, Kassa H, Tischler ML, Xiao L (2004) Host-adapted Cryptosporidium spp. in Canada geese (Branta canadensis). App Environ Microbiol 70:4211–4421

Zogaris S. (2017). Conservation study of the Mediterranean Killifish Aphanius fasciatus in Akrotiri Marsh, (Akrotiri SBA, Cyprus) - final report. Darwin Project DPLUS034 “Akrotiri Marsh Restoration: a flagship wetland in the Cyprus SBAs BirdLife Cyprus”. Nicosia Cyprus. Unpublished final report, 64 pp.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Katerina Georgiou for her assistance with collecting the samples.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Kyriacos A Hasapis, Eleni Tsouma, and Konstantina Sotiriadou: formal analysis and investigation, visualization, and writing—original draft. Nicolaos Kassinis: material collection. Chad Schou: material collection, formal investigation, and editing. Iris Charalambidou: conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft, and supervision. Panagiotis Karanis: conceptualization, methodology, writing—review and editing, and overall supervision. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All applicable guidelines for the care or use of animals were followed.

Consent for publication

All authors agreed to the publication of the manuscript.

Additional information

Handling Editor: Una Ryan

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Hasapis, K.A., Charalambidou, I., Tsouma, E. et al. First detection of Cryptosporidium proventriculi from wild birds in Cyprus. Parasitol Res 122, 201–205 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-022-07717-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-022-07717-y