Abstract

Background

It is estimated that about half of cancer patients use at least one form of complementary and alternative medicines (CAM) in their life but there is a strong reticence of patients in talking about CAM with their oncologist. Primary aim of this study was to inform patients about CAM, focusing on their supposed benefits, toxicities and interactions with conventional therapeutic agents. The study also explored patients’ perception about CAM and ascertained the level of CAM use among cancer patients of an Italian academic hospital.

Methods

From April 2016 to April 2017, the observational pilot trial “CAMEO-PRO” prospectively enrolled 239 cancer patients that were invited to attend a tutorial about CAM at the Department of oncology, University Hospital of Udine, Italy. Before and after the informative session, patients were asked to fill a questionnaire reporting their knowledge and opinion about CAM.

Results

Overall, 163 (70%) women and 70 (30%) men were enrolled. Median age was 61 years. At study entry, 168 (72%) patients declared they had never been interested in this topic previously; 24 patients (11%) revealed the use of a type of alternative therapy and 58 (28%) revealed the use of complementary therapy. In total, 139 (55.2%) patients attended the informative session. Bowker’s test of symmetry demonstrated statistically significant opinion’s change after the session on 9 out of 14 explored items.

Conclusions

Informative sessions seem to have a relevant impact on patients’ perceptions and opinions about CAM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The acronym CAM stands for the complementary and alternative medicines which comprise the non-conventional medicines sometimes proposed as alternatives to the medical prescribed treatments or proposed in association with conventional medicine. However, there is no real dichotomy between “alternative” and “complementary” medicines, since treatments may be alternative or complementary depending on patients’ intent when using them. In the oncological field, CAM have always been a subject of debate, both for their underverified clinical value and for their potential damages to individual patients and society (Bozza et al. 2015).

It is estimated that in the US approximately 30–40% of the general population use CAM and, among those who use them, about 80% comprise patients with chronic pathologies (Harris et al. 2012). The European figure, obtained from a survey conducted on 956 patients in 14 countries (Molassiotis et al. 2005), confirms the growth trend of CAM reporting that 35.9% of oncological patients use them during their course of care (Kessler et al. 2001). However, data on the Italian situation are limited. A study of 803 oncological patients from the Tuscany region focusing solely on the complementary therapies reported 37.9% of users. Among them, 89.6% reported receiving benefit and 66.3% only informed their physician about their use (Bonacchi et al. 2014). A recent multicentre survey conducted in Italy on 468 patients, revealed that nearly 49% were presently using or had recently used CAM. Notably, in this study, the definition of CAM included herbal remedies, supplements and vitamins (Berretta et al. 2017).

From the case studies of patients interviewed about their use of CAM, the reasons cited for their use were improvement of psychophysical wellbeing in 76% of the cases and, in the oncological field, to strengthen the ability of the body to fight cancer (11–41% cases) or to reduce the side effects of chemotherapy (3–74%). Many patients declared they have benefited from the use of CAM use even if these benefits did not often coincide with the initial reason for using them. Only a small number of the interviewed (less than 5%) reported collateral effects, most of which had been transient.

CAM treatments account for a significant part of the public spending in several countries. In the US, it is estimated that annual spending regarding alternative treatments is around 27 million dollars per year (Eisenberg et al. 1998). The Italian figure, according to Bonacchi et al. (2014), reported that 39.3% of complementary therapy users has to face an annual expenditure of over 250 euros. Therefore, close to the primary objective of the demonstration of their efficacy, it is crucial to evaluate cost-effectiveness of these therapies.

Age, sex and level of education constitute predictors of CAM use (Gansler et al. 2008). Pre-existing psychiatric illnesses (Burstein et al. 1999), an inauspicious diagnosis with a brief expectation of life (Risberg et al. 1997) and participation in support groups (Boon et al. 2000) are other factors associated with CAM use.

According to the European survey (Molassiotis et al. 2005), principal sources of information are friends or relatives in 87.1% of cases, the Internet and mass media in 37.7%, and physicians and health workers in 21.6%. Patients do not often declare the use of CAM to their physician (Bonacchi et al. 2014), if not expressly requested to do so (Metz et al. 2001). Despite the popularity of CAM, many oncologists revealed little knowledge of the subject (Newell and Sanson-Fisher 2000) and less than a quarter started a discussion with their patients about this topic (Schofield et al. 2003).

Among the potential toxicities of CAM, there are side effects due to their mechanisms of action: indirect effects due to the interaction with other medicines with a consequent reduction of the effectiveness of these last, or onset of unexpected events (Tables 1, 2). Furthermore, it is not uncommon for patients using CAM to delay in accessing potentially effective official therapies prescribed for the care and control of the symptoms caused by the tumor.

Alternative therapies have been shown to be ineffective in almost all cases: however, some randomized trials involving the vast and varied panorama of the complementary therapies have suggested they may have some benefits, although the evidence is still limited and in some cases lacking of scientific validation. These studies are often limited by lack of a control group, the placebo effect, and the difficulty in evaluating particular outcomes such as quality of life.

Patients and methods

Complementary and Alternative MEdicine in Oncology-Physicians infoRm Oncological patients (CAMEO-PRO) is an observational prospective study, active in our center from April 2016 to April 2017.

This spontaneous and non-sponsored study, approved by an ethics committee, consecutively enrolled patients who were receiving, or had previously received, at least one oncological treatment at Department of Oncology, Academic Hospital of Udine.

At the time of enrollment, the patients received information about the study. After signing a written informed consent, patients were asked to fill in an anonymous questionnaire (Q1). They were then invited to attend an information session about complementary and alternative medicines in oncology. The trial participation was voluntary and did not interfere with clinical practice. After the session, the attending patients were required to fill in a second anonymous questionnaire (Q2) to assess any changes in their opinions about the topic. A number was assigned to the patients and to the baseline questionnaire, to correctly match any second questionnaire after the session.

Inclusion criteria were diagnosis of cancer, to be followed at the Department of Oncology of Udine, to have received at least one anti-cancer treatment, the ability to provide informed consent and Karnofsky performance status ≥ 60.

The Q1 questionnaire (“Appendix 1”), based on those already published by Molassiotis and Saghatchian, was designed to elicit the patient’s demographic characteristics, social and family situation, clinical data reported by the patient and, more importantly, their perceptions about the disease and the treatment received, knowledge about CAM, their source of information, the possible uses of CAM, the reasons for using them and their satisfaction with CAM. The last part of the questionnaire comprised statements regarding CAM for which patients were asked to express a level of agreement.

The Q2 questionnaire (“Appendix 2”) replicated the last part of the previous questionnaire to detect any change in perceptions and opinions after the information session and the patient’s satisfaction with the content and delivery of the session.

The 1.5-h information sessions were conducted by doctors with the support of a video projector and slides. The first hour was devoted to illustrating the most popular alternative and complementary therapies with a special focus on the evidence available to date, toxicities, possible interactions with oncological treatment and the need to declare their use during clinical visits; the second part of the session was reserved for questions and discussion.

Statistical analysis

Patients’ characteristics were summarized by descriptive analysis, with a special emphasis on demographic and social aspects.

Continuous variables were reported though the median and interquartile range, whereas categorical variables were described by frequency distributions.

Differences in baseline answers, according to the patients’ characteristics and use of CAM, were investigated by means of chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test as per sample size constrains.

Stratification was applied to highlight whether baseline characteristics could influence the answering patterns.

Differences in answering patterns before and after the information session were investigated through Bowker’s test of symmetry. The statistical significance level was set at P < 0.05.

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS software, Version 9.4 [SAS Institute Inc. (2014) Cary, NC].

Results

A total of 239 patients were enrolled, 163 females (68.2%), 70 males (29.3%); 6 patients did not declare their sex (2.5%). The median age was 61 years (range 23–8). The most frequent educational level was high school diploma; 98 patients (41.2%) had a high school and 68 (29.1%) a junior high school degree. The primary tumor sites involved were the breast (42.4%), gastrointestinal tract (27.8%), lung (11.7%), and genitourinary tract (10.8%). More than 90% of patients declared they knew the purpose of their treatment, only 1.7% declared that they did not know it, and 6.9% were not sure (Table 3).

Patients were asked to state their main sources of information about health. It was possible to cite more than one source: the most frequent were family doctors (70.1%), the internet (41.4%), family (20.1%), friends (17.8%) and other health professionals, e.g., naturopath (9.8%).

Most patients, 168 (72.7%), stated that they had never been interested in CAM before, in contrast to almost a third (27.2%) who reported they were already interested before enrollment in the study. The alternative therapies mentioned more frequently were the Di Bella multitherapy (83.0%), Stamina (33.3%) and Simoncini (13.4%), Artemisia (14.5%), Hamer (18.2%) and Pantellini (10.7%) methods. Among the complementary therapies most cited were acupuncture (74.1%), homeopathy (71.7%), herbal remedies (34.9%), reflexology (30.7%), aromatherapy (25.3%) and reiki (22.9%).

A total of 24 patients (11% of those who responded to the question) declared their use of at least one alternative treatment during their oncological care path. The main alternative treatments used were the Pantellini (7 cases), Artemisia (6 cases) and Essiac (4 cases) approaches. Furthermore, 58 patients (28.4% of respondents) declared the use of at least one complementary treatment. The main complementary treatments used were homeopathy (30 cases), herbal remedies (23 cases), reflexology (14 cases), acupuncture (13 cases), and reiki (7 cases).

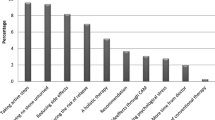

The 24 patients using CAM, cited the most frequent reasons for their use as being “to have more chances of healing”, “to prevent or to reduce collateral effects from conventional medicine”, “to regain better psychophysical wellbeing” and “Firmly believing in their being unharmful even if probably ineffective”. Satisfaction levels for CAM were very high, with more than half the patients revealing a level of satisfaction higher than 6. Only a small percentage of respondents gave feedback about the economic burden of CAM; for this reason, it was not possible to draw any conclusions on this issue. (Table 4).

Considering both alternative and complementary medicines, age younger than 45 (P = 0.0053), female gender (P = 0.0128), senior high school education (P = 0.0382) and breast cancer (P = 0.0455) were factors associated with the use of CAM. Compared to the remaining study population, patients using CAM declared a greater degree of agreement with the following items in the basal questionnaire: “I clearly know the difference between alternative and complementary treatment” (P < 0.001), “Even if they do not work as traditional therapies, CAM can help quality of life” (P < 0.001), “Chemotherapy is harmful and causes side effects that negatively affect patients’ quality of life” (P = 0.0033), “Even if the alternative therapies are probably ineffective, they are unharmful” (P = 0.0027), “Complementary therapies may reduce the side effects of conventional medicine” (P = 0.0188), “CAM fill the need for more humane and personalized treatments” (P = 0.035), “I have chosen or would choose CAM” (P < 0.001), “I would use alternative therapies if I had no more viable conventional medicine options” (P = 0.0023).

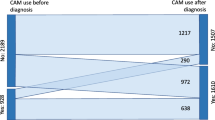

A total of 139 patients attended information sessions. Bowker’s test of symmetry demonstrated statistically significative opinion changes after the session regarding 9 out of 14 explored items. Changes in opinions and their statistical relevance are presented in Table 5.

The Q2 questionnaire also focused on the interest and usefulness of the information session and patients were asked about their thoughts on the topic. Notably, positive feedback was obtained: 83.9% of respondents reported that the session was very useful and 71.5% declared that after the session the topics were clearer.

Patients who attended the information session, compared to those who did not, did not show different characteristics or degrees of agreement with the items of the basal questionnaire, except for an increased use of CAM (48 observed versus 28 expected, P = 0.0042).

Patients who attended the information session and declared they had used CAM showed a statistically significative change in opinion for the following items: “I clearly know the difference between alternative and complementary treatment” (P = 0.0064), “Even if they do not work as traditional therapies, CAM can help quality of life” (P = 0.0145), “Even if the alternative therapies are probably ineffective, they are unharmful” (P = 0.0130), “The use of alternative therapies can hinder a correct therapeutic path” (P = 0.0079), and “I have chosen or would choose to use CAM” (P = 0.028).

Discussion

The present study has provided real-world data about the use of complementary and alternative medicines among Italian cancer patients.

The results of our study are in line with the existing literature and confirm sex, age and education as predictive factors of CAM use (Molassiotis et al. 2005; Gansler et al. 2008; Saghatchian et al. 2014).

At Q1, only 27.3% of patients declared to be interested in CAM and nearly 70% declared their family doctor as a source of information. These data are of strong interest. First, they indicate the prominent role of general practitioners in providing advice that may influence patients’ choices. Second, these results underline the fact that, despite the spread and abuse of technology, most patients maintained their physician as the main source of health news. Nonetheless, the internet was frequently used to acquire information about CAM (42.5% of cases), followed by family and friends/acquaintances.

This knowledge about the main sources could be particularly useful to put in place improvements in the quality of information.

About one-third of patients declared the use of some form of CAM. This figure is apparently smaller than that reported in other countries and in Italy (Molassiotis et al. 2005; Bonacchi et al. 2014; Berretta et al. 2017). The most used alternative treatments were Pantellini’s and Artemisia’s methods, with a considerably high degree of satisfaction. Furthermore, the most used complementary therapies were homeopathy and herbal remedies, also with a high degree of satisfaction.

On the other hand, a high number of patients reported a very high level of satisfaction regarding communication with oncologists about the diagnosis, prognosis and purpose of treatment. This finding made it impossible to highlight any association between satisfaction level on communication and the use of CAM. Paradoxically, however, nearly 8% of patients were not sure of, or did not know, the purpose of the treatment prescribed.

More than half the patients attended the information session: significant opinion changes were observed in all participants and also among patients who had reported a previous use of CAM. These results suggest that the more skeptical patients also need to be correctly informed to enhance their perception of CAM. The positive impact of the sessions on patients’ opinion corroborates the great need to properly inform cancer patients to give them the opportunity to raise their awareness.

The peculiar features of this study include patient anonymity, and the information sessions; however, the questionnaire’s structure and the complete freedom to fill in it allowed many fields to be left uncompleted. Consequently, some issues were difficult to interpret, although the pattern of missing answers could be informative in itself.

Although the survey was not able to quantify the economic burden of CAM, the problem of the cost of these treatments is particularly relevant. A topic dear to those who propose CAM is the alleged conspiracy of pharmaceuticals companies that would gain from conventional therapies and from vaccines; however, the costs of vitamin supplements or ineffective drugs paradoxically have a greater impact on health public spending.

An open issue that still needs a clarification is the ambiguity of the definition of CAM, distinguishing and recognizing the value of complementary therapies that can satisfy, or already satisfy, the criteria of scientific validation.

Conclusions

Educational sessions about CAM are welcome for patients and should be included in regular cancer care to fill the gap of information not always satisfied by health care providers.

When evidence-based informative sessions on CAM are conducted by trained oncologists, patients are more willing to share their opinion with physicians and seem to be open to discuss this issue.

General practitioners, as principal source of information for patients, have a crucial role in promoting appropriate use of CAM (i.e., evidence-based complementary medicine) and may help to discourage inappropriate use of alternative medicine. They should be reached by tailored educational campaigns.

Our study demonstrates that patient’s educational campaigns are feasible to conduce, well accepted by patients and have a sustainable cost–benefit ratio.

References

Ashar B, Vargo E (1996) Shark cartilage-induced hepatitis. Ann Intern Med 125:780–781

Berretta M, Della Pepa C, Tralongo P et al (2017) Use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in cancer patients: An Italian multicenter survey. Oncotarget 8:24401–24414

Bonacchi A, Fazzi L, Toccafondi A et al (2014) Use and perceived benefits of complementary therapies by cancer patients receiving conventional treatment in Italy. J Pain Symptom Manag 47:26–34

Boon H, Stewart M, Kennard MA et al (2000) Use of complementary/alternative medicine by breast cancer survivors in Ontario: prevalence and perceptions. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 18:2515–2521

Boudreau MD, Beland FA (2006) An evaluation of the biological and toxicological properties of Aloe barbadensis (Miller), Aloe vera. J Environ Sci Health Part C Environ Carcinog Ecotoxicol Rev 24:103–154

Bozza C, Agostinetto E, Gerratana L et al (2015) Complementary and alternative medicine in oncology. Recenti Prog Med 106:601–607

Budzinski JW, Foster BC, Vandenhoek S et al (2000) An in vitro evaluation of human cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibition by selected commercial herbal extracts and tinctures. Phytomed Int J Phytother Phytopharm 7:273–282

Burstein HJ, Gelber S, Guadagnoli E et al (1999) Use of alternative medicine by women with early-stage breast cancer. N Engl J Med 340:1733–1739

Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL et al (1998) Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990–1997: results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA 280:1569–1575

Ernst E (2002) The risk-benefit profile of commonly used herbal therapies: Ginkgo, St. John’s Wort, Ginseng, Echinacea, Saw Palmetto, and Kava. Ann Intern Med 136:42–53

Gansler T, Kaw C, Crammer C et al (2008) A population-based study of prevalence of complementary methods use by cancer survivors: a report from the American Cancer Society’s studies of cancer survivors. Cancer 113:1048–1057

Golden EB, Lam PY, Kardosh A et al (2009) Green tea polyphenols block the anticancer effects of bortezomib and other boronic acid-based proteasome inhibitors. Blood 113:5927–5937

Haller CA, Benowitz NL (2000) Adverse cardiovascular and central nervous system events associated with dietary supplements containing ephedra alkaloids. N Engl J Med 343:1833–1838

Harris PE, Cooper KL, Relton C et al (2012) Prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use by the general population: a systematic review and update. Int J Clin Pract 66:924–939

Jatoi A, Ellison N, Burch PA et al (2003) A phase II trial of green tea in the treatment of patients with androgen independent metastatic prostate carcinoma. Cancer 97:1442–1446

Kessler RC, Davis RB, Foster DF et al (2001) Long-term trends in the use of complementary and alternative medical therapies in the United States. Ann Intern Med 135:262–268

Lee AH, Ingraham SE, Kopp M et al (2006) The incidence of potential interactions between dietary supplements and prescription medications in cancer patients at a Veterans Administration Hospital. Am J Clin Oncol 29:178–182

MacGregor FB, Abernethy VE, Dahabra S et al (1989) Hepatotoxicity of herbal remedies. BMJ 299:1156–1157

Metz JM, Jones H, Devine P et al (2001) Cancer patients use unconventional medical therapies far more frequently than standard history and physical examination suggest. Cancer J Sudbury Mass 7:149–154

Miller DR, Anderson GT, Stark JJ et al (1998) Phase I/II trial of the safety and efficacy of shark cartilage in the treatment of advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 16:3649–3655

Moertel CG, Fleming TR, Rubin J et al (1982) A clinical trial of amygdalin (Laetrile) in the treatment of human cancer. N Engl J Med 306:201–206

Molassiotis A, Fernadez-Ortega P, Pud D et al (2005) Use of complementary and alternative medicine in cancer patients: a European survey. Ann Oncol 16:655–663

Newell S, Sanson-Fisher RW (2000) Australian oncologists’ self-reported knowledge and attitudes about non-traditional therapies used by cancer patients. Med J Aust 172:110–113

Risberg T, Kaasa S, Wist E et al (1997) Why are cancer patients using non-proven complementary therapies? A cross-sectional multicentre study in Norway. Eur J Cancer Oxf Engl 1990 33:575–580

Saghatchian M, Bihan C, Chenailler C et al (2014) Exploring frontiers: use of complementary and alternative medicine among patients with early-stage breast cancer. Breast Edinb Scotl 23:279–285

Schofield PE, Juraskova I, Butow PN (2003) How oncologists discuss complementary therapy use with their patients: an audio-tape audit. Support Care Cancer 11:348–355

Sparreboom A, Cox MC, Acharya MR et al (2004) Herbal remedies in the United States: potential adverse interactions with anticancer agents. J Clin Oncol 22:2489–2503

Teschke R, Schwarzenboeck A, Eickhoff A et al (2013) Clinical and causality assessment in herbal hepatotoxicity. Expert Opin Drug Saf 12:339–366

Vaccini la bufala dei costi e degli incassi di Big pharma—Mondo Sanità—Blog—Repubblica.it. http://bocci.blogautore.repubblica.it/2017/06/24/vaccini-la-bufala-dei-costi-e-degli-incassi-di-big-pharma/. Accessed 30 June 2017

Yang HN, Kim DJ, Kim YM et al (2010) Aloe-induced toxic hepatitis. J Korean Med Sci 25:492–495

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Anna Vallerugo, MA, for her writing assistance.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Q1 questionnaire

Definition of CAM: Non-conventional medicine alternative or complementary to “official medicine”

The purpose of these questionnaires is to assess your knowledge of alternative and complementary therapies and what is your opinion on these treatments.

Thank you for letting us know which alternative and complementary therapies you have already heard of and the reasons why you chose to undergo/not to undergo CAM treatments.

All information provided will be treated confidentially.

Appendix 2: Q2 questionnaire

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bozza, C., Gerratana, L., Basile, D. et al. Use and perception of complementary and alternative medicine among cancer patients: the CAMEO-PRO study. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 144, 2029–2047 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-018-2709-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-018-2709-2